Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Coming of Age in Samoa

1928 book by Margaret Mead From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation is a 1928 book by American anthropologist Margaret Mead based upon her research and study of youth – primarily adolescent girls – on the island of Taʻū in American Samoa. The book details the sexual life of teenagers in Samoan society in the early 20th century, and theorizes that culture has a leading influence on psychosexual development.

First published in 1928, the book launched Mead as a pioneering researcher and as the most famous anthropologist in the world. Since its first publication, Coming of Age in Samoa was the most widely read book in the field of anthropology until Napoleon Chagnon's Yanomamö: The Fierce People overtook it.[1] The book has sparked years of ongoing and intense debate and controversy on questions pertaining to society, culture, and science. It is a key text in the nature versus nurture debate, as well as in discussions on issues relating to family, adolescence, gender, social norms, and attitudes.[2]

In the 1980s, Derek Freeman contested many of Mead's claims, and argued that she was hoaxed into counterfactually believing that Samoan culture had more relaxed sexual norms than Western culture.[3] However, several members of the anthropology community have rejected Freeman's criticism, accusing him of cherry picking his data, and misrepresenting both Mead's research and the interviews that he conducted.[4][5][6] Mead's field work for "Coming of Age" was also scrutinized, and major discrepancies were found between her published statements and her field data.[7][8] Some Samoans are critical of what Mead wrote of their culture, especially her claim that adolescent promiscuity was socially acceptable in Samoa in the 1920s.[9]

Coming of Age in Samoa entered the public domain in the United States in 2024.[10]

Remove ads

Content

Summarize

Perspective

Foreword

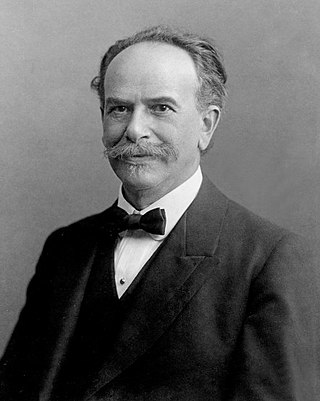

In the foreword to Coming of Age in Samoa, Mead's advisor, Franz Boas, writes:

"Courtesy, modesty, good manners, conformity to definite ethical standards are universal, but what constitutes courtesy, modesty, good manners, and definite ethical standards is not universal. It is instructive to know that standards differ in the most unexpected ways."[11]

Boas went on to point out that, at the time of publication, many Americans had begun to discuss the problems faced by young people (particularly women) as they pass through adolescence as "unavoidable periods of adjustment". Boas felt that a study of the problems faced by adolescents in another culture would be illuminating.[11]

Introduction

Mead introduces the book with a general discussion of the problems facing adolescents in modern society and the various approaches to understanding these problems: religion, philosophy, educational theory, and psychology. She discusses various limitations in each approach and then introduces the new field of anthropology as a promising alternative science based on analyzing social structures and dynamics. She contrasts the methodology of the anthropologist with other scientific studies of behavior and the obvious reasons that controlled experiments are so much more difficult for anthropology than other sciences. For this reason her methodology is one of studying societies in their natural environment. Rather than select a culture that is fairly well understood such as Europe or America, she chooses South Sea island people because their culture is radically different from Western culture and likely to yield more useful data as a result. However, in doing so she introduces new complexity in that she must first understand and communicate to her readers the nature of South Sea culture itself rather than delve directly into issues of adolescence as she could in a more familiar culture. Once she has an understanding of Samoan culture she will delve into the specifics of how adolescent education and socialization are carried out in Samoan culture and contrast it with Western culture.[12]

Mead described the goal of her research as follows:

"I have tried to answer the question which sent me to Samoa: Are the disturbances which vex our adolescents due to the nature of adolescence itself or to the civilization? Under different conditions does adolescence present a different picture?"[12]

To answer this question, she conducted her study among a small group of Samoans. She found a village of 600 people on the island of Ta'ū, in which, over a period of between six and nine months, she got to know, lived with, observed, and interviewed (having learnt some Samoan) 68 young women between the ages of 9 and 20. Mead studied daily living, education, social structures and dynamics, rituals, etiquette, etc.[12]

Samoan life and education

Mead begins with the description of a typical idyllic day in Samoa. She then describes child education, starting with the birth of children, which is celebrated with a lengthy ritual feast. After birth, however, Mead describes how children are mostly ignored -- with girl children sometimes explicitly ritually ignored -- after birth up to puberty. She describes the various methods of disciplining children. Most involve some sort of corporal punishment, such as hitting with hands, palm fronds, or shells. However, the punishment is mostly ritualistic and not meant to inflict serious harm. Children are expected to contribute meaningful work from a very early age. Initially, young children of both sexes help to care for infants. As the children grow older, however, the education of the boys shifts to fishing, while the girls focus more on child care. However, the concept of age for the Samoans is not the same as in the West. Samoans do not keep track of birthdays, and they judge maturity not on actual number of years alive, but rather on the outward physical changes in the child.[citation needed]

For the adolescent girls, status is primarily a question of whom they will marry. Mead also describes adolescence and the time before marriage as the high point of a Samoan girl's life:

"But the seventeen year old girl does not wish to marry – not yet. It is better to live as a girl with no responsibility, and a rich variety of experience. This is the best period of her life."[13]: 14–39

Samoan household

The next section describes the structure of a Samoan village: "a Samoan village is made up of some thirty to forty households, each of which is presided over by a head man". Each household is an extended family including widows and widowers. The household shares houses communally: each household has several houses but no members have an ownership or permanent residence of any specific building. The houses may not all be within the same part of the village.[citation needed]

The head man of the household has ultimate authority over the group. Mead describes how the extended family provides security and safety for Samoan children. Children are likely to be near relatives no matter where they are, and any child that is missing will be found quite rapidly. The household also provides freedom for children including girls. According to Mead, if a girl is unhappy with the particular relatives she happens to live with, she can always simply move to a different home within the same household. Mead also describes the various and fairly complex status relations which entail a combination of factors such as a role in the household, the household's status within the village, the age of the individual, etc. There are also many rules of etiquette for requesting and granting favors.[13]: 39–58

Samoan social structures and rules

Mead describes the many group structures and dynamics within Samoan culture. The forming of groups is an important part of Samoan life from early childhood when young children form groups for play and mischief. There are several different kinds of possible group structures in Samoan culture. Relations flow down from chiefs and heads of households; men designate another man to be their aid and surrogate in courting rituals; men form groups for fishing and other work activities; women form groups based on tasks such as child care and household relations. Mead describes examples of such groups and describes the complex rules that govern how they are formed and how they function. Her emphasis is on Samoan adolescent girls, but as elsewhere she needs to also describe Samoan social structures for the entire culture to give a complete picture.[citation needed]

Mead believes that the complex and mandatory rules that govern these various groups mean that the traditional Western concept of friendship as a bond entered into voluntarily by two people with compatible interests is all but meaningless for Samoan girls: "friendship is so patterned as to be meaningless. I once asked a young married woman if a neighbor with whom she was always upon the most uncertain and irritated terms was a friend of hers. 'Why, of course, her mother's father's father, and my father's mother's father were brothers.'"[citation needed]

The ritual requirements (such as being able to remember specifics about family relations and roles) are far greater for men than women. This also translates into significantly more responsibility being placed on men than women: "a man who commits adultery with a chief's wife was beaten and banished, sometime even drowned by the outraged community, but the woman was only cast out by her husband".[citation needed]

Mead devotes a whole chapter to Samoan music and the role of dancing and singing in Samoan culture. She views these as significant because they violate the norms of what Samoans define as good behavior in all other activities and provide a unique outlet for Samoans to express their individuality. According to Mead there is ordinarily no greater social failing than demonstrating an excess of pride, or as the Samoans describe it, "presuming above one's age". However, this is not the case when it comes to singing and dancing. In these activities, individuality and creativity are the most highly praised attributes, and children are free to express themselves to the fullest extent of their capabilities rather than being concerned with appropriate behavior based on age and status:

The attitude of the elders toward precocity in ... singing or dancing, is in striking contrast to their attitude towards every other form of precocity. On the dance floor the dreaded accusation "You are presuming above your age" is never heard. Little boys who would be rebuked or whipped for such behavior on any other occasion are allowed to preen themselves, to swagger and bluster and take the limelight without a word of reproach. The relatives crow with delight over a precocity for which they would hide their heads in shame were it displayed in any other sphere ... Often a dancer does not pay enough attention to her fellow dancers to avoid continually colliding with them. It is a genuine orgy of aggressive individualistic behavior.[13]: 59–122

Personality, sexuality, and old age

Mead describes the psychology of the individual Samoan as being simpler, more honest, and less driven by sexual neuroses than the West. She describes Samoans as being much more comfortable with issues such as menstruation and more casual about non-monogamous sexual relations.[14] Part of the reason for this is the extended family structure of Samoan villages. Conflicts that might result in arguments or breaks within a traditional Western family can be defused in Samoan families simply by having one of the parties to the conflict relocate to a different home that is part of the household within the village.[15] Another reason Mead cites is that Samoans do not seem eager to give judgmental answers to questions. Mead describes how one of the things that made her research difficult was that Samoans would often answer just about every question with non-committal answers, the Samoan equivalent to shrugging one's shoulders and saying: "Who knows?"[citation needed]

Mead concludes the section of the book dealing with Samoan life with a description of Samoan old age. Samoan women in old age "are usually more of a power within the household than the old men. The men rule partly by the authority conferred by their titles, but their wives and sisters rule by force of personality and knowledge of human nature."[13]: 122–195

Educational problems: American and Samoan contrasts

Mead concluded that the passage from childhood to adulthood (adolescence) in Samoa was a smooth transition and not marked by the emotional or psychological distress, anxiety, or confusion seen in the United States.[citation needed]

Mead concluded that this was due to the Samoan girl's belonging to a stable, monocultural society, surrounded by role models, and where nothing concerning the basic human facts of copulation, birth, bodily functions, or death, was hidden. The Samoan girl was not pressured to choose from among a variety of conflicting values, as was the American girl. Mead commented, somewhat satirically:

... [an American] girl's father may be a Presbyterian, an imperialist, a vegetarian, a teetotaller, with a strong literary preference for Edmund Burke, a believer in the open shop and a high tariff, who believes that women's place is in the home, that young girls should wear corsets, not roll their stockings, not smoke, nor go riding with young men in the evening. But her mother's father may be a Low Episcopalian, a believer in high living, a strong advocate of States' Rights and the Monroe Doctrine, who reads Rabelais, likes to go to musical shows and horse races. Her aunt is an agnostic, an ardent advocate of women's rights, an internationalist who rests all her hopes on Esperanto, is devoted to Bernard Shaw, and spends her spare time in campaigns of anti-vivisection. Her elder brother, whom she admires exceedingly, has just spent two years at Oxford. He is an Anglo-Catholic, an enthusiast concerning all things medieval, writes mystical poetry, reads Chesterton, and means to devote his life to seeking for the lost secret of medieval stained glass. Her mother's younger brother ...[13]: 195–234

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

On publication, the book generated a great deal of coverage both in the academic world and in the popular press. Mead's publisher (William Morrow) had lined up many endorsements from well known academics such as anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski and psychologist John Watson. Their praise was a major public relations coup for Morrow and drew popular attention to the book. Academic interest was soon followed by sensational headlines such as "Samoa is the Place for Women" and that Samoa is "Where Neuroses Cease".[4]: 113

Impact on anthropology

For most anthropologists before Mead, detailed immersive fieldwork was not a common practice. Although subsequent reviews of her work have revealed faults by the standards of modern anthropology, at the time the book was published the idea of living with native people was fairly ground breaking. The use of cross-cultural comparison to highlight issues within Western society was highly influential and contributed greatly to the heightened awareness of anthropology and ethnographic study in the United States. It established Mead as a substantial figure in American anthropology, a position she would maintain for the next fifty years.[4]: 94–95

Many field and comparative studies by anthropologists since Coming of Age in Samoa have found that adolescence is not experienced in the same way in all societies. Systematic cross-cultural study of adolescence by Schlegel and Barry, for example, concluded that adolescents experience harmonious relations with their families in most non-industrialized societies around the world.[16] They find that, when family members need each other throughout their lives, independence, as expressed in adolescent rebelliousness, is minimal and counterproductive. Adolescents are likely to be rebellious only in industrialized societies practicing neolocal residence patterns (in which young adults must move their residence away from their parents). Neolocal residence patterns result from young adults living in industrial societies who move to take new jobs or in similar geographically mobile populations. Thus, Mead's analysis of adolescent conflict is upheld in the comparative literature on societies worldwide.[17]

Social influences and reactions

As Boas and Mead expected, this book upset many Westerners when it first appeared in 1928. Many American readers felt shocked by her observation that young Samoan women deferred marriage for many years while enjoying casual sex before eventually choosing a husband. As a landmark study regarding sexual mores, the book was highly controversial and frequently came under attack on ideological grounds. For example, the National Catholic Register argued that Mead’s findings were merely a projection of her own sexual beliefs and reflected her desire to eliminate restrictions on her own sexuality.[18] The conservative Intercollegiate Studies Institute listed Coming of Age in Samoa as #1 on its list of the "50 Worst Books of the Twentieth Century".[19] The book was also included among the "10 Books That Screwed Up the World", listed in the book of this title by Benjamin Wiker.[20]

Critique of Mead's methodology and conclusions

Although Coming of Age received significant interest and praise from the academic community, Mead's research methodology also came under criticism from several reviewers and fellow anthropologists. Mead was criticized for not separating her personal speculation and opinions from her ethnographic description of Samoan life and for making sweeping generalizations based on a relatively short period of study.[citation needed]

For example, Nels Anderson wrote about the book: "If it is science, the book is somewhat of a disappointment. It lacks a documental base. It is given too much to interpretation instead of description. Dr. Mead forgets too often that that she is an anthropologist and gets her own personality involved with her materials."[4]: 114–115

Shortly after Mead’s death, Derek Freeman published a book, Margaret Mead and Samoa, that claimed Mead failed to apply the scientific method and that her assertions were unsupported. This criticism is dealt with in detail in the section below.[21]

Remove ads

The Mead–Freeman controversy

Summarize

Perspective

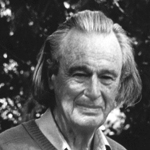

Derek Freeman, a New Zealand anthropologist became the most prominent critic of Coming of Age in Samoa, publishing two books attacking her findings in 1983 and 1998. Freeman had lived in Samoa from 1940 to 1943,[22] and studied missionary records from Samoa during his doctoral training at Cambridge.[23] In 1965, he began fieldwork in Samoa, motivated in part by skepticism of Mead's research.[24] He criticized Mead's work in a 1968 paper to the Australian Association of Social Anthropology, arguing that Mead had mischaracterized Samoa as a sexually liberated society when in fact it was characterized by sexual repression and violence and adolescent delinquency. Completing his manuscript of Margaret Mead and Samoa in 1977 he wrote Mead offering her to read it before publication, but Mead was by then seriously ill with cancer and was unable to respond; she died the next year.[25] Freeman's critiques became a media spectacle with a front-page New York Times article in January 1983, two months before his first of two books on Mead was published.[26]: 242–243 On the whole, anthropologists have rejected the notion that Mead's conclusions rested on the validity of a single interview with a single person and find instead that Mead based her conclusions on the sum of her observations and interviews during her time in Samoa and that the status of the single interview did not falsify her work.[27] Others such as Orans maintained that even though Freeman's critique was invalid, Mead's study was not sufficiently scientifically rigorous to support the conclusions she drew.[28][page needed]

Freeman's 1983 book

In 1983, five years after Mead had died, Freeman published Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth, in which he challenged all of Mead's major findings.

Freeman argued that Mead had misunderstood Samoan culture when she argued that Samoan culture did not place many restrictions on youths' sexual explorations. Freeman argued instead that Samoan culture prized female chastity and virginity and that Mead had been misled by her female Samoan informants.[29]: 232–240 Freeman found that the Samoan islanders whom Mead had depicted in such utopian terms were intensely competitive and had murder and rape rates higher than those in the United States.[29]: 164 Furthermore, the men were intensely sexually jealous, which contrasted sharply with Mead's depiction of "free love" among the Samoans.[29]: 241–244 [30] Freeman stated that the idea that premarital sex was an expected practice in Samoa was "so preposterously at variance with the realities of Samoan life that a special explanation is called for … all the indications are that the young Margaret Mead was, as a kind of joke, deliberately misled by her adolescent informants."[29]: 240

In 1988, he participated in the filming of Margaret Mead and Samoa, directed by Frank Heimans, which claims to document one of Mead's original informants, now an elderly woman, swearing that the information she and her friend provided Mead when they were teenagers was false; one of the girls would say of Mead on videotape years later:

We girls would pinch each other and tell her we were out with the boys. We were only joking but she took it seriously. As you know, Samoan girls are terrific liars and love making fun of people but Margaret thought it was all true.[31]

Another of Mead's statements on which Freeman focused was her claim that through the use of chicken blood, Samoan girls could and do lie about their status of virginity.[32] Freeman pointed out that virginity of the bride is so crucial to the status of Samoan men that they have a specific ritual in which the bride's hymen is manually ruptured in public, by the groom himself or by the chief, making deception via chicken blood impossible. On this ground, Freeman argued that Mead must have based her account on (false) hearsay from non-Samoan sources.[33]

The argument hinged on the place of the taupou system in Samoan society. According to Mead, the taupou system is one of institutionalized virginity for young women of high rank, and it is exclusive to women of high rank. According to Freeman, all Samoan women emulated the taupou system, and Mead's informants denied having engaged in casual sex as young women and claimed that they had lied to Mead.[34]

Anthropological reception and reactions

After an initial flurry of discussion, many anthropologists concluded that Freeman systematically misrepresented Mead's views on the relationship between nature and nurture, as well as the data on Samoan culture. According to Freeman's colleague Robin Fox, Freeman "seemed to have a special place in hell reserved for Margaret Mead, for reasons not at all clear at that time".[35] First, these critics have speculated that he waited until Mead died before publishing his critique so that she would not be able to respond. However, in 1978, Freeman sent a revised manuscript to Mead, but she was ill and died a few months later without responding.[34]: xvi

Second, Freeman's critics point out that, by the time he arrived on the scene, Mead's original informants were old women, grandmothers, and had converted to Christianity, so their testimony to him may not have been accurate. They further argue that Samoan culture had changed considerably in the decades following Mead's original research; after intense missionary activity, many Samoans had come to adopt the same sexual standards as the Americans who were once so shocked by Mead's book. They suggested that such women, in this new context, were unlikely to speak frankly about their adolescent behavior. Further, they suggested that these women might not be as forthright and honest about their sexuality when speaking to an elderly man as they would have been speaking to a woman near their own age.[17]

Some anthropologists criticized Freeman on methodological and empirical grounds.[36][37] For example, they stated that Freeman had conflated publicly articulated ideals with behavioral norms – that is, while many Samoan women would admit in public that it is ideal to remain a virgin, in practice they engaged in high levels of premarital sex and boasted about their sexual affairs among themselves.[38] Freeman's own data documented the existence of premarital sexual activity in Samoa. In a western Samoan village, he documented that 20% of 15 year-olds, 30% of 16 year-olds, and 40% of 17 year-olds had engaged in premarital sex.[34]: 238–240 In 1983, the American Anthropological Association held a special session to discuss Freeman's book, to which they did not invite him. Their criticism was made formal at the 82nd annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association the next month in Chicago, where a special session, to which Freeman was not invited, was held to discuss his book.[39] They passed a motion declaring Freeman's Margaret Mead and Samoa "poorly written, unscientific, irresponsible, and misleading". Freeman commented that "to seek to dispose of a major scientific issue by a show of hands is a striking demonstration of the way in which belief can come to dominate the thinking of scholars".[39]

In the years that followed, anthropologists vigorously debated these issues. Two scholars who published on the issue include Appell, who stated "I found Freeman's argument to be completely convincing";[40] and Brady, who stated "Freeman's book discovers little but tends to reinforce what many anthropologists already suspected" regarding the adequacy of Mead's ethnography.[41] They were supported by several others.[42]

Eleanor Leacock traveled to Samoa in 1985 and undertook research among the youth living in urban areas. The research results indicate that the assertions of Derek Freeman were seriously flawed. Leacock pointed out that Mead's famous Samoan fieldwork was undertaken on an outer island that had not been colonialized. Freeman, meanwhile, had undertaken fieldwork in an urban slum plagued by drug abuse, structural unemployment, and gang violence. Lowell Holmes – who completed a lesser-publicized re-study – commented later: "Mead was better able to identify with, and therefore establish rapport with, adolescents and young adults on issues of sexuality than either I (at age 29, married with a wife and child) or Freeman, ten years my senior."[43]

Much like Mead's work, Freeman's account has been challenged as being ideologically driven to support his own theoretical viewpoint (sociobiology and interactionism), as well as assigning Mead a high degree of gullibility and bias. Freeman's refutation of Samoan sexual mores has been challenged, in turn, as being based on public declarations of sexual morality, virginity, and taupou rather than on actual sexual practices within Samoan society during the period of Mead's research.[44]

In 1996, Martin Orans published his review[45] of Mead's notes preserved at the Library of Congress, crediting her for leaving all her recorded data as available to the general public. Orans concludes that Freeman's basic criticism (that Mead was duped by ceremonial virgin Fa'apua'a Fa'amu who later swore to Freeman that she had played a joke on Mead) was false for several reasons: first, Mead was well aware of the forms and frequency of Samoan joking; second, she provided a careful account of the sexual restrictions on ceremonial virgins that corresponds to Fa'apua'a Fa'amu's account to Freeman; and third, that Mead's notes make clear that she had reached her conclusions about Samoan sexuality before meeting Fa'apua'a Fa'amu. He therefore concludes, contrary to Freeman, that Mead was never the victim of a hoax.[45]

Orans points out that Mead's data supports several different conclusions, and that Mead's conclusions hinge on an interpretive, rather than positivist, approach to culture. Orans concludes that due to Mead's interpretive approach – common to most contemporary cultural anthropology – her hypotheses and conclusions are essentially unfalsifiable and therefore "not even wrong".[45]: 11–13

In his 2001 obituary in The New York Times, John Shaw stated that Freeman's thesis, though upsetting many, had by the time of his death led to a re-evaluation of Mead's work on Samoa.[46] Recent work has nonetheless challenged Freeman's critique.[47] A frequent criticism of Freeman is that he regularly misrepresented Mead's research and views.[48][page needed][49] In a 2009 evaluation of the debate, anthropologist Paul Shankman concluded:[48]

There is now a large body of criticism of Freeman's work from a number of perspectives in which Mead, Samoa, and anthropology appear in a very different light than they do in Freeman's work. Indeed, the immense significance that Freeman gave his critique looks like 'much ado about nothing' to many of his critics.

In her 2015 book Galileo's Middle Finger, Alice Dreger argues that Freeman's accusations were unfounded and misleading. A detailed review of the controversy by Paul Shankman, published by the University of Wisconsin Press in 2009, supports the contention that Mead's research was essentially correct and concludes that Freeman cherry-picked his data and misrepresented both Mead and Samoan culture.[50][page needed][51][52] A survey of 301 anthropology faculty in the United States in 2016 had two thirds agreeing with a statement that Mead "romanticizes the sexual freedom of Samoan adolescents" and half agreeing that it was ideologically motivated.[53]

Freeman's 1998 book

In 1998, Freeman published another book The Fateful Hoaxing of Margaret Mead.[54] It included new material, in particular interviews that Freeman called of "exceptional historical significance" and "of quite fundamental importance" of one of Mead's then-adolescent informants by a Samoan chief from the National University of Samoa (in 1988 and 1993) and of her daughter (in 1995).[54]: ix Correspondence of 1925–1926 between Franz Boas and Margaret Mead was also newly available to Freeman. He concludes in the introduction to the book that "her exciting revelations about sexual behavior were in some cases merely the extrapolations of whispered intimacies, whereas those of greatest consequence were the results of a prankish hoax".[54]: 1

Freeman argues that Mead collected other evidence that contradicts her own conclusion, such as a tutor who related that as of puberty girls were always escorted by female family members.[54]: 127 He also claims that because of a decision to take ethnological trips to Fitiuta, only eight weeks remained for her primary research into adolescent girls, and it was now "practically impossible" to find time with the sixty-six girls she was to study, because the government school had reopened.[54]: 130–131 With the remaining time, she instead went to Ofu, and the bulk of her research came from speaking with her two Samoan female companions, Fa'apua'a and Fofoa. Freeman claims Mead's letters to Boas reflect that she was influenced by studies of sexuality from Marquesas Islands, and that she was seeking to confirm the same information by questioning Fa'apua'a and Fofoa.[54]: 139 She sent her conclusions to Boas on March 14[54]: 142–143, 146 and with "little left to do"[54]: 148 she cut short her trip.[54]: 146

Freeman claimed that "no systematic, firsthand investigation of the sexual behavior of her sample of adolescent girls was ever to be undertaken. Instead, Margaret Mead's account of adolescent sexual behavior in Coming of Age in Samoa and elsewhere was based on what she had been told by Fa'apua'a and Fofoa, supplemented by other such inquiries that she had previously made."[54]: 147 As Fa'apua'a told Freeman, in her 80s, that she and her friend had been joking, Freeman defends her testimony in the introduction of his second book about Mead: Both that the octagenarian's memory was very good, and that she swore on the Bible, as a Christian, that it was true.[54]: 12, 7

In 2009, a detailed review of the controversy was published by Paul Shankman.[4] It supports the contention that Mead's research was essentially correct, and concludes that Freeman cherry-picked his data and misrepresented both Mead and Samoan culture.[4][5][6]

Broader impact of the controversy

Freeman's books were received enthusiastically by communities of scientists who believed that sexual mores were more or less universal across cultures.[55][56] While nurture-oriented anthropologists are more inclined to agree with Mead's conclusions, some non-anthropologists who take a nature-oriented approach follow Freeman's lead, such as Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, biologist Richard Dawkins, evolutionary psychologist David Buss, science writer Matt Ridley, classicist Mary Lefkowitz[57][page needed].

In the popular press, Mead's influential role in American culture became a reason for interest in challenges to her approach. A Time magazine article published before Freeman's book was released, stated that "if Freeman is correct, Mead succeeded in swaying the minds of liberal educators and psychologists mostly by dramatic but mistaken references to primitive living."[26]: 244–245 Nancy Lutkehaus argues that "Freeman's critique of Mead offered individuals like [Allan] Bloom [, author of The Closing of the American Mind], who considered the principale of cultural relativism … to be the source of many of the nation's contemporary propblems, additional fuel for their antiliberal, antimulticulturalist arguments."

The controversy was featured on the Phil Donahue Show, was the primary subject of the documentary Margaret Mead and Samoa, and of David Williamson's play Heretic.[26]: 242–252

Remove ads

See also

- Culture of American Samoa

- Heretic, a play by Australian playwright David Williamson that explores Freeman's reactions to Mead.

- The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads