Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

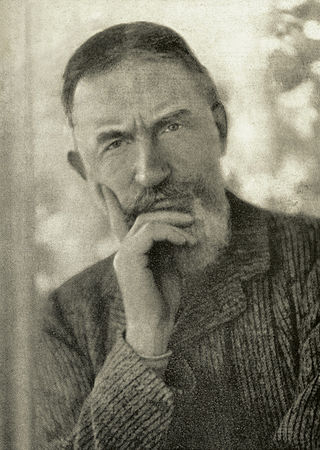

George Bernard Shaw

Irish playwright, critic, and polemicist (1856–1950) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 1880s to his death and beyond. He wrote more than sixty plays, including major works such as Man and Superman (1902), Pygmalion (1913) and Saint Joan (1923). With a range incorporating both contemporary satire and historical allegory, Shaw became the leading dramatist of his generation, and in 1925 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Born in Dublin, in 1876 Shaw moved to London, where he struggled to establish himself as a writer and novelist, and embarked on a rigorous process of self-education. By the mid-1880s he had become a respected theatre and music critic. Following a political awakening, he joined the gradualist Fabian Society and became its most prominent pamphleteer. Shaw had been writing plays for years before his first public success, Arms and the Man in 1894. Influenced by Henrik Ibsen, he sought to introduce a new realism into English-language drama, using his plays as vehicles to disseminate his political, social and religious ideas. By the early twentieth century his reputation as a dramatist was secured with a series of critical and popular successes that included Major Barbara, The Doctor's Dilemma, and Caesar and Cleopatra.

Shaw's expressed views were often contentious; he promoted eugenics and alphabet reform, and opposed vaccination and organised religion. He courted unpopularity by denouncing both sides in the First World War as equally culpable, and although not a republican, castigated British policy on Ireland in the postwar period. These stances had no lasting effect on his standing or productivity as a dramatist; the inter-war years saw a series of often ambitious plays, which achieved varying degrees of popular success. In 1938 he provided the screenplay for a filmed version of Pygmalion for which he received an Academy Award. His appetite for politics and controversy remained undiminished; by the late 1920s, he had largely renounced Fabian Society gradualism, and often wrote and spoke favourably of dictatorships of the right and left—he expressed admiration for both Mussolini and Stalin. In the final decade of his life, he made fewer public statements but continued to write prolifically until shortly before his death, aged ninety-four, having refused all state honours, including the Order of Merit in 1946.

Since Shaw's death scholarly and critical opinion about his works has varied, but he has regularly been rated among British dramatists as second only to Shakespeare; analysts recognise his extensive influence on generations of English-language playwrights. The word Shavian has entered the language as encapsulating Shaw's ideas and his means of expressing them.

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Early years

Shaw was born at 3 Upper Synge Street[n 1] in Portobello, a lower-middle-class part of Dublin.[2] He was the youngest child and only son of George Carr Shaw and Lucinda Elizabeth (Bessie) Shaw (née Gurly). His elder siblings were Lucinda (Lucy) Frances and Elinor Agnes. The Shaw family was of English descent and belonged to the dominant Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland;[n 2] George Carr Shaw, an ineffectual alcoholic, was among the family's less successful members.[3] His relatives secured him a sinecure in the civil service, from which he was pensioned off in the early 1850s; thereafter he worked irregularly as a corn merchant.[2] In 1852 he married Bessie Gurly; in the view of Shaw's biographer Michael Holroyd she married to escape a tyrannical great-aunt.[4] If, as Holroyd and others surmise, George's motives were mercenary, then he was disappointed, as Bessie brought him little of her family's money.[5] She came to despise her ineffectual and often drunken husband, with whom she shared what their son later described as a life of "shabby-genteel poverty".[4]

By the time of Shaw's birth his mother had become close to George John Lee, a flamboyant figure well known in Dublin's musical circles. Shaw retained a lifelong obsession that Lee might have been his biological father;[6] there is no consensus among Shavian scholars on the likelihood of this.[7][8][9][10] The young Shaw suffered no harshness from his mother, but he later recalled that her indifference and lack of affection hurt him deeply.[11] He found solace in the music that abounded in the house. Lee was a conductor and teacher of singing; Bessie had a fine mezzo-soprano voice and was much influenced by Lee's unorthodox method of vocal production. The Shaws' house was often filled with music, with frequent gatherings of singers and players.[2]

In 1862 Lee and the Shaws agreed to share a house, No. 1 Hatch Street, in an affluent part of Dublin, and a country cottage on Dalkey Hill, overlooking Killiney Bay.[12] Shaw, a sensitive boy, found the less salubrious parts of Dublin shocking and distressing, and was happier at the cottage. Lee's students often gave him books, which the young Shaw read avidly;[13] thus, as well as gaining a thorough musical knowledge of choral and operatic works, he became familiar with a wide spectrum of literature.[14]

Between 1865 and 1871 Shaw attended four schools, all of which he hated.[15][n 3] His experiences as a schoolboy left him disillusioned with formal education: "Schools and schoolmasters", he later wrote, were "prisons and turnkeys in which children are kept to prevent them disturbing and chaperoning their parents."[16] In October 1871 he left school to become a junior clerk in a Dublin firm of land agents, where he worked hard, and quickly rose to become head cashier.[6] During this period, Shaw was known as "George Shaw"; after 1876, he dropped the "George" and styled himself "Bernard Shaw".[n 4]

In June 1873 Lee left Dublin for London and never returned. A fortnight later, Bessie followed him; the two girls joined her.[6][n 5] Shaw's explanation of why his mother followed Lee was that without the latter's financial contribution the joint household had to be broken up.[20] Left in Dublin with his father, Shaw compensated for the absence of music in the house by teaching himself to play the piano.[6]

London

Early in 1876 Shaw learned from his mother that Agnes was dying of tuberculosis. He resigned from the land agents, and in March travelled to England to join his mother and Lucy at Agnes's funeral. He never again lived in Ireland, and did not visit it for twenty-nine years.[2]

Initially, Shaw refused to seek clerical employment in London. His mother allowed him to live free of charge in her house in South Kensington, but he nevertheless needed an income. He had abandoned a teenage ambition to become a painter, and had not yet thought of writing for a living, but Lee found a little work for him, ghost-writing a musical column printed under Lee's name in a satirical weekly, The Hornet.[2] Lee's relations with Bessie deteriorated after their move to London.[n 6] Shaw maintained contact with Lee, who found him work as a rehearsal pianist and occasional singer.[21][n 7]

Eventually Shaw was driven to applying for office jobs. In the interim he secured a reader's pass for the British Museum Reading Room (the forerunner of the British Library) and spent most weekdays there, reading and writing.[25] His first attempt at drama, begun in 1878, was a blank-verse satirical piece on a religious theme. It was abandoned unfinished, as was his first try at a novel. His first completed novel, Immaturity (1879), was too grim to appeal to publishers and did not appear until the 1930s.[6] He was employed briefly by the newly formed Edison Telephone Company in 1879–80 and, as in Dublin, achieved rapid promotion. Nonetheless, when the Edison firm merged with the rival Bell Telephone Company, Shaw chose not to seek a place in the new organisation.[26] Thereafter he pursued a full-time career as an author.[27]

For the next four years Shaw made a negligible income from writing, and was subsidised by his mother.[28] In 1881, for the sake of economy, and increasingly as a matter of principle, he became a vegetarian.[6] In the same year he suffered an attack of smallpox; eventually he grew a beard to hide the resultant facial scar.[29][n 8] In rapid succession he wrote two more novels: The Irrational Knot (1880) and Love Among the Artists (1881), but neither found a publisher; each was serialised a few years later in the socialist magazine Our Corner.[32][n 9]

In 1880 Shaw began attending meetings of the Zetetical Society, whose objective was to "search for truth in all matters affecting the interests of the human race".[35] Here he met Sidney Webb, a junior civil servant who, like Shaw, was busy educating himself. Despite difference of style and temperament, the two quickly recognised qualities in each other and developed a lifelong friendship. Shaw later reflected: "You knew everything that I didn't know and I knew everything you didn't know ... We had everything to learn from one another and brains enough to do it".[36]

Shaw's next attempt at drama was a one-act playlet in French, Un Petit Drame, written in 1884 but not published in his lifetime.[37] In the same year the critic William Archer suggested a collaboration, with a plot by Archer and dialogue by Shaw.[38] The project foundered, but Shaw returned to the draft as the basis of Widowers' Houses in 1892,[39] and the connection with Archer proved of immense value to Shaw's career.[40]

Political awakening: Marxism, socialism, Fabian Society

On 5 September 1882 Shaw attended a meeting at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon, addressed by the political economist Henry George.[41] Shaw then read George's book Progress and Poverty, which awakened his interest in economics.[42] He began attending meetings of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), where he discovered the writings of Karl Marx, and thereafter spent much of 1883 reading Das Kapital. He was not impressed by the SDF's founder, H. M. Hyndman, whom he found autocratic, ill-tempered and lacking leadership qualities. Shaw doubted the ability of the SDF to harness the working classes into an effective radical movement and did not join it—he preferred, he said, to work with his intellectual equals.[43]

After reading a tract, Why Are The Many Poor?, issued by the recently formed Fabian Society,[n 10] Shaw went to the society's next advertised meeting, on 16 May 1884.[45] He became a member in September,[45] and before the year's end had provided the society with its first manifesto, published as Fabian Tract No. 2.[46] He joined the society's executive committee in January 1885, and later that year recruited Webb and also Annie Besant, a fine orator.[45]

"The most striking result of our present system of farming out the national Land and capital to private individuals has been the division of society into hostile classes, with large appetites and no dinners at one extreme, and large dinners and no appetites at the other"

Shaw, Fabian Tract No. 2: A Manifesto (1884).[47]

From 1885 to 1889 Shaw attended the fortnightly meetings of the British Economic Association; it was, Holroyd observes, "the closest Shaw had ever come to university education". This experience changed his political ideas; he moved away from Marxism and became an apostle of gradualism.[48] When in 1886–87 the Fabians debated whether to embrace anarchism, as advocated by Charlotte Wilson, Besant and others, Shaw joined the majority in rejecting this approach.[48] After a rally in Trafalgar Square addressed by Besant was violently broken up by the authorities on 13 November 1887 ("Bloody Sunday"), Shaw became convinced of the folly of attempting to challenge police power.[49] Thereafter he largely accepted the principle of "permeation" as advocated by Webb: the notion whereby socialism could best be achieved by infiltration of people and ideas into existing political parties.[50]

Throughout the 1880s the Fabian Society remained small, its message of moderation frequently unheard among more strident voices.[51] Its profile was raised in 1889 with the publication of Fabian Essays in Socialism, edited by Shaw who also provided two of the essays. The second of these, "Transition", details the case for gradualism and permeation, asserting that "the necessity for cautious and gradual change must be obvious to everyone".[52] In 1890 Shaw produced Tract No. 13, What Socialism Is,[46] a revision of an earlier tract in which Charlotte Wilson had defined socialism in anarchistic terms.[53] In Shaw's new version, readers were assured that "socialism can be brought about in a perfectly constitutional manner by democratic institutions".[54]

Novelist and critic

The mid-1880s marked a turning point in Shaw's life, both personally and professionally: he lost his virginity, had two novels published, and began a career as a critic.[55] He had been celibate until his twenty-ninth birthday, when his shyness was overcome by Jane (Jenny) Patterson, a widow some years his senior.[56] Their affair continued, not always smoothly, for eight years. Shaw's sex life has caused much speculation and debate among his biographers, but there is a consensus that the relationship with Patterson was one of his few non-platonic romantic liaisons.[n 11]

The published novels, neither commercially successful, were his two final efforts in this genre: Cashel Byron's Profession written in 1882–83, and An Unsocial Socialist, begun and finished in 1883. The latter was published as a serial in To-Day magazine in 1884, although it did not appear in book form until 1887. Cashel Byron appeared in magazine and book form in 1886.[6]

In 1884 and 1885, through the influence of Archer, Shaw was engaged to write book and music criticism for London papers. When Archer resigned as art critic of The World in 1886, he secured the succession for Shaw.[61] The two figures in the contemporary art world whose views Shaw most admired were William Morris and John Ruskin, and he sought to follow their precepts in his criticisms.[61] Their emphasis on morality appealed to Shaw, who rejected the idea of art for art's sake, and insisted that all great art must be didactic.[62]

Of Shaw's various reviewing activities in the 1880s and 1890s it was as a music critic that he was best known.[63] After serving as deputy in 1888, he became musical critic of The Star in February 1889, writing under the pen-name Corno di Bassetto.[64][n 12] In May 1890 he moved back to The World, where he wrote a weekly column as "G.B.S." for more than four years. In the 2016 version of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Robert Anderson writes, "Shaw's collected writings on music stand alone in their mastery of English and compulsive readability."[66] Shaw ceased to be a salaried music critic in August 1894, but published occasional articles on the subject throughout his career, his last in 1950.[67]

From 1895 to 1898, Shaw was the theatre critic for The Saturday Review, edited by his friend Frank Harris. As at The World, he used the by-line "G.B.S." He campaigned against the artificial conventions and hypocrisies of the Victorian theatre and called for plays of real ideas and true characters. By this time he had embarked in earnest on a career as a playwright: "I had rashly taken up the case; and rather than let it collapse I manufactured the evidence".[6]

Playwright and politician: 1890s

After using the plot of the aborted 1884 collaboration with Archer to complete Widowers' Houses (it was staged twice in London, in December 1892), Shaw continued writing plays. At first he made slow progress; The Philanderer, written in 1893 but not published until 1898, had to wait until 1905 for a stage production. Similarly, Mrs Warren's Profession (1893) was written five years before publication and nine years before reaching the stage.[n 13]

Shaw's first play to bring him financial success was Arms and the Man (1894), a mock-Ruritanian comedy satirising conventions of love, military honour and class.[6] The press found the play overlong, and accused Shaw of mediocrity,[69] sneering at heroism and patriotism,[70] heartless cleverness,[71] and copying W. S. Gilbert's style.[69][n 14] The public took a different view, and the management of the theatre staged extra matinée performances to meet the demand.[73] The play ran from April to July, toured the provinces and was staged in New York.[72] It earned him £341 in royalties in its first year, a sufficient sum to enable him to give up his salaried post as a music critic.[74] Among the cast of the London production was Florence Farr, with whom Shaw had a romantic relationship between 1890 and 1894, much resented by Jenny Patterson.[75]

The success of Arms and the Man was not immediately replicated. Candida, which presented a young woman making a conventional romantic choice for unconventional reasons, received a single performance in South Shields in 1895;[76] in 1897 a playlet about Napoleon called The Man of Destiny had a single staging at Croydon.[77] In the 1890s Shaw's plays were better known in print than on the West End stage; his biggest success of the decade was in New York in 1897, when Richard Mansfield's production of the historical melodrama The Devil's Disciple earned the author more than £2,000 in royalties.[2]

In January 1893, as a Fabian delegate, Shaw attended the Bradford conference which led to the foundation of the Independent Labour Party.[78] He was sceptical about the new party,[79] and scorned the likelihood that it could switch the allegiance of the working class from sport to politics.[80] He persuaded the conference to adopt resolutions abolishing indirect taxation, and taxing unearned income "to extinction".[81] Back in London, Shaw produced what Margaret Cole, in her Fabian history, terms a "grand philippic" against the minority Liberal administration that had taken power in 1892. To Your Tents, O Israel! excoriated the government for ignoring social issues and concentrating solely on Irish Home Rule, a matter Shaw declared of no relevance to socialism.[80][82][n 15] In 1894 the Fabian Society received a substantial bequest from a sympathiser, Henry Hunt Hutchinson—Holroyd mentions £10,000. Webb, who chaired the board of trustees appointed to supervise the legacy, proposed to use most of it to found a school of economics and politics. Shaw demurred; he thought such a venture was contrary to the specified purpose of the legacy. He was eventually persuaded to support the proposal, and the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) opened in the summer of 1895.[83]

By the later 1890s Shaw's political activities lessened as he concentrated on making his name as a dramatist.[84] In 1897 he was persuaded to fill an uncontested vacancy for a "vestryman" (parish councillor) in London's St Pancras district. At least initially, Shaw took to his municipal responsibilities seriously;[n 16] when London government was reformed in 1899 and the St Pancras vestry became the Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras, he was elected to the newly formed borough council.[86]

In 1898, as a result of overwork, Shaw's health broke down. He was nursed by Charlotte Payne-Townshend, a rich Anglo-Irish woman whom he had met through the Webbs. The previous year she had proposed that she and Shaw should marry.[87] He had declined, but when she insisted on nursing him in a house in the country, Shaw, concerned that this might cause scandal, agreed to their marriage.[2] The ceremony took place on 1 June 1898, in the register office in Covent Garden.[88] The bride and bridegroom were both aged forty-one. In the view of the biographer and critic St John Ervine, "their life together was entirely felicitous".[2] There were no children of the marriage, which it is generally believed was never consummated; whether this was wholly at Charlotte's wish, as Shaw liked to suggest, is less widely credited.[89][90][91][92][93] In the early weeks of the marriage Shaw was much occupied writing his Marxist analysis of Wagner's Ring cycle, published as The Perfect Wagnerite late in 1898.[94] In 1906 the Shaws found a country home in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire; they renamed the house "Shaw's Corner", and lived there for the rest of their lives. They retained a London flat in the Adelphi and later at Whitehall Court.[95]

Stage success: 1900–1914

During the first decade of the twentieth century, Shaw secured a firm reputation as a playwright. In 1904 J. E. Vedrenne and Harley Granville-Barker established a company at the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square, Chelsea to present modern drama. Over the next five years they staged fourteen of Shaw's plays.[96][n 17] The first, John Bull's Other Island, a comedy about an Englishman in Ireland, attracted leading politicians and was seen by Edward VII, who laughed so much that he broke his chair.[97] The play was withheld from Dublin's Abbey Theatre, for fear of the affront it might provoke,[6] although it was shown at the city's Royal Theatre in November 1907.[98] Shaw later wrote that William Butler Yeats, who had requested the play, "got rather more than he bargained for ... It was uncongenial to the whole spirit of the neo-Gaelic movement, which is bent on creating a new Ireland after its own ideal, whereas my play is a very uncompromising presentment of the real old Ireland."[99][n 18] Nonetheless, Shaw and Yeats were close friends; Yeats and Lady Gregory tried unsuccessfully to persuade Shaw to take up the vacant co-directorship of the Abbey Theatre after J. M. Synge's death in 1909.[102] Shaw admired other figures in the Irish Literary Revival, including George Russell[103] and James Joyce,[104] and was a close friend of Seán O'Casey, who was inspired to become a playwright after reading John Bull's Other Island.[105]

Man and Superman, completed in 1902, was a success both at the Royal Court in 1905 and in Robert Loraine's New York production in the same year. Among the other Shaw works presented by Vedrenne and Granville-Barker were Major Barbara (1905), depicting the contrasting morality of arms manufacturers and the Salvation Army;[106] The Doctor's Dilemma (1906), a mostly serious piece about professional ethics;[107] and Caesar and Cleopatra, Shaw's counterblast to Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, seen in New York in 1906 and in London the following year.[108]

Now prosperous and established, Shaw experimented with unorthodox theatrical forms described by his biographer Stanley Weintraub as "discussion drama" and "serious farce".[6] These plays included Getting Married (premiered 1908), The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet (1909), Misalliance (1910), and Fanny's First Play (1911). Blanco Posnet was banned on religious grounds by the Lord Chamberlain (the official theatre censor in England), and was produced instead in Dublin; it filled the Abbey Theatre to capacity.[109] Fanny's First Play, a comedy about suffragettes, had the longest initial run of any Shaw play—622 performances.[110]

Androcles and the Lion (1912), a less heretical study of true and false religious attitudes than Blanco Posnet, ran for eight weeks in September and October 1913.[111] It was followed by one of Shaw's most successful plays, Pygmalion, written in 1912 and staged in Vienna the following year, and in Berlin shortly afterwards.[112] Shaw commented, "It is the custom of the English press when a play of mine is produced, to inform the world that it is not a play—that it is dull, blasphemous, unpopular, and financially unsuccessful. ... Hence arose an urgent demand on the part of the managers of Vienna and Berlin that I should have my plays performed by them first."[113] The British production opened in April 1914, starring Sir Herbert Tree and Mrs Patrick Campbell as, respectively, a professor of phonetics and a cockney flower-girl. There had earlier been a romantic liaison between Shaw and Campbell that caused Charlotte Shaw considerable concern, but by the time of the London premiere it had ended.[114] The play attracted capacity audiences until July, when Tree insisted on going on holiday, and the production closed. His co-star then toured with the piece in the US.[115][116][n 19]

Fabian years: 1900–1913

In 1899, when the Boer War began, Shaw wished the Fabians to take a neutral stance on what he deemed, like Home Rule, to be a "non-Socialist" issue. Others, including the future Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald, wanted unequivocal opposition, and resigned from the society when it followed Shaw.[118] In the Fabians' war manifesto, Fabianism and the Empire (1900), Shaw declared that "until the Federation of the World becomes an accomplished fact we must accept the most responsible Imperial federations available as a substitute for it".[119]

As the new century began, Shaw became increasingly disillusioned by the limited impact of the Fabians on national politics.[120] Thus, although a nominated Fabian delegate, he did not attend the London conference at the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street in February 1900, that created the Labour Representation Committee—precursor of the modern Labour Party.[121] By 1903, when his term as borough councillor expired, he had lost his earlier enthusiasm, writing: "After six years of Borough Councilling I am convinced that the borough councils should be abolished".[122] Nevertheless, in 1904 he stood in the London County Council elections. After an eccentric campaign, which Holroyd characterises as "[making] absolutely certain of not getting in", he was duly defeated. It was Shaw's final foray into electoral politics.[122] Nationally, the 1906 general election produced a huge Liberal majority and an intake of 29 Labour members. Shaw viewed this outcome with scepticism; he had a low opinion of the new prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, and saw the Labour members as inconsequential: "I apologise to the Universe for my connection with such a body".[123]

In the years after the 1906 election, Shaw felt that the Fabians needed fresh leadership, and saw this in the form of his fellow-writer H. G. Wells, who had joined the society in February 1903.[124] Wells's ideas for reform—particularly his proposals for closer cooperation with the Independent Labour Party—placed him at odds with the society's "Old Gang", led by Shaw.[125] According to Cole, Wells "had minimal capacity for putting [his ideas] across in public meetings against Shaw's trained and practised virtuosity".[126] In Shaw's view, "the Old Gang did not extinguish Mr Wells, he annihilated himself".[126] Wells resigned from the society in September 1908;[127] Shaw remained a member, but left the executive in April 1911. He later wondered whether the Old Gang should have given way to Wells some years earlier: "God only knows whether the Society had not better have done it".[128][129] Although less active—he blamed his advancing years—Shaw remained a Fabian.[130]

In 1912 Shaw invested £1,000 for a one-fifth share in the Webbs' new publishing venture, a socialist weekly magazine called The New Statesman, which appeared in April 1913. He became a founding director, publicist, and in due course a contributor, mostly anonymously.[131] He was soon at odds with the magazine's editor, Clifford Sharp, who by 1916 was rejecting his contributions—"the only paper in the world that refuses to print anything by me", according to Shaw.[132]

First World War

"I see the Junkers and Militarists of England and Germany jumping at the chance they have longed for in vain for many years of smashing one another and establishing their own oligarchy as the dominant military power of the world."

Shaw: Common Sense About the War (1914).[133]

After the First World War began in August 1914, Shaw produced his tract Common Sense About the War, which argued that the warring nations were equally culpable.[6] Such a view was anathema in an atmosphere of fervent patriotism, and offended many of Shaw's friends; Ervine records that "[h]is appearance at any public function caused the instant departure of many of those present."[134]

Despite his errant reputation, Shaw's propagandist skills were recognised by the British authorities, and early in 1917 he was invited by Field Marshal Haig to visit the Western Front battlefields. Shaw's 10,000-word report, which emphasised the human aspects of the soldier's life, was well received, and he became less of a lone voice. In April 1917 he joined the national consensus in welcoming America's entry into the war: "a first class moral asset to the common cause against junkerism".[135]

Three short plays by Shaw were premiered during the war. The Inca of Perusalem, written in 1915, encountered problems with the censor for burlesquing not only the enemy but the British military command; it was performed in 1916 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre.[136] O'Flaherty V.C., satirising the government's attitude to Irish recruits, was banned in the UK and was presented at a Royal Flying Corps base in Belgium in 1917. Augustus Does His Bit, a genial farce, was granted a licence; it opened at the Royal Court in January 1917.[137]

Ireland

Shaw had long supported the principle of Irish Home Rule within the British Empire (which he thought should become the British Commonwealth).[138] In April 1916 he wrote scathingly in The New York Times about militant Irish nationalism: "In point of learning nothing and forgetting nothing these fellow-patriots of mine leave the Bourbons nowhere."[139] Total independence, he asserted, was impractical; alliance with a bigger power (preferably England) was essential.[139] The Dublin Easter Rising later that month took him by surprise. After its suppression by British forces, he expressed horror at the summary execution of the rebel leaders, but continued to believe in some form of Anglo-Irish union. In How to Settle the Irish Question (1917), he envisaged a federal arrangement, with national and imperial parliaments. Holroyd records that by this time the separatist party Sinn Féin was in the ascendency, and Shaw's and other moderate schemes were forgotten.[140]

In the postwar period, Shaw despaired of the British government's coercive policies towards Ireland,[141] and joined his fellow-writers Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton in publicly condemning these actions.[142] The Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 led to the partition of Ireland between north and south, a provision that dismayed Shaw.[141] In 1922 civil war broke out in the south between its pro-treaty and anti-treaty factions, the former of whom had established the Irish Free State.[143] Shaw visited Dublin in August, and met Michael Collins, then head of the Free State's Provisional Government.[144] Shaw was much impressed by Collins, and was saddened when, three days later, the Irish leader was ambushed and killed by anti-treaty forces.[145] In a letter to Collins's sister, Shaw wrote: "I met Michael for the first and last time on Saturday last, and am very glad I did. I rejoice in his memory, and will not be so disloyal to it as to snivel over his valiant death".[146] Shaw remained a British subject all his life, but took dual British-Irish nationality in 1934.[147]

1920s

Shaw's first major work to appear after the war was Heartbreak House, written in 1916–17 and performed in 1920. It was produced on Broadway in November, and was coolly received; according to The Times: "Mr Shaw on this occasion has more than usual to say and takes twice as long as usual to say it".[148] After the London premiere in October 1921 The Times concurred with the American critics: "As usual with Mr Shaw, the play is about an hour too long", although containing "much entertainment and some profitable reflection".[149] Ervine in The Observer thought the play brilliant but ponderously acted, except for Edith Evans as Lady Utterword.[150]

Shaw's largest-scale theatrical work was Back to Methuselah, written in 1918–20 and staged in 1922. Weintraub describes it as "Shaw's attempt to fend off 'the bottomless pit of an utterly discouraging pessimism'".[6] This cycle of five interrelated plays depicts evolution, and the effects of longevity, from the Garden of Eden to the year 31,920 AD.[151] Critics found the five plays strikingly uneven in quality and invention.[152][153][154] The original run was brief, and the work has been revived infrequently.[155][156] Shaw felt he had exhausted his remaining creative powers in the huge span of this "Metabiological Pentateuch". He was now sixty-seven, and expected to write no more plays.[6]

This mood was short-lived. In 1920 Joan of Arc was proclaimed a saint by Pope Benedict XV; Shaw had long found Joan an interesting historical character, and his view of her veered between "half-witted genius" and someone of "exceptional sanity".[157] He had considered writing a play about her in 1913, and the canonisation prompted him to return to the subject.[6] He wrote Saint Joan in the middle months of 1923, and the play was premiered on Broadway in December. It was enthusiastically received there,[158] and at its London premiere the following March.[159] In Weintraub's phrase, "even the Nobel prize committee could no longer ignore Shaw after Saint Joan". The citation for the literature prize for 1925 praised his work as "... marked by both idealism and humanity, its stimulating satire often being infused with a singular poetic beauty".[160] He accepted the award, but rejected the monetary prize that went with it, on the grounds that "My readers and my audiences provide me with more than sufficient money for my needs".[161][n 20]

After Saint Joan, it was five years before Shaw wrote a play. From 1924, he spent four years writing what he described as his "magnum opus", a political treatise entitled The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism.[163] The book was published in 1928 and sold well.[2][n 21] At the end of the decade Shaw produced his final Fabian tract, a commentary on the League of Nations. He described the League as "a school for the new international statesmanship as against the old Foreign Office diplomacy", but thought that it had not yet become the "Federation of the World".[165]

Shaw returned to the theatre with what he called "a political extravaganza", The Apple Cart, written in late 1928. It was, in Ervine's view, unexpectedly popular, taking a conservative, monarchist, anti-democratic line that appealed to contemporary audiences. The premiere was in Warsaw in June 1928, and the first British production was two months later, at Sir Barry Jackson's inaugural Malvern Festival.[2] The other eminent creative artist most closely associated with the festival was Sir Edward Elgar, with whom Shaw enjoyed a deep friendship and mutual regard.[166] He described The Apple Cart to Elgar as "a scandalous Aristophanic burlesque of democratic politics, with a brief but shocking sex interlude".[167]

During the 1920s Shaw began to lose faith in the idea that society could be changed through Fabian gradualism, and became increasingly fascinated with dictatorial methods. In 1922 he had welcomed Mussolini's accession to power in Italy, observing that amid the "indiscipline and muddle and Parliamentary deadlock", Mussolini was "the right kind of tyrant".[168] Shaw was prepared to tolerate certain dictatorial excesses; Weintraub in his ODNB biographical sketch comments that Shaw's "flirtation with authoritarian inter-war regimes" took a long time to fade, and Beatrice Webb thought he was "obsessed" about Mussolini.[169]

1930s

"We the undersigned are recent visitors to the USSR ... We desire to record that we saw nowhere evidence of economic slavery, privation, unemployment and cynical despair of betterment. ... Everywhere we saw [a] hopeful and enthusiastic working-class ... setting an example of industry and conduct which would greatly enrich us if our systems supplied our workers with any incentive to follow it."

Letter to The Manchester Guardian, 2 March 1933, signed by Shaw and 20 others.[170]

Shaw's enthusiasm for the Soviet Union dated to the early 1920s when he had hailed Lenin as "the one really interesting statesman in Europe".[171] Having turned down several chances to visit, in 1931 he joined a party led by Nancy Astor.[172] The carefully managed trip culminated in a lengthy meeting with Stalin, whom Shaw later described as "a Georgian gentleman" with no malice in him.[173] At a dinner given in his honour, Shaw told the gathering: "I have seen all the 'terrors' and I was terribly pleased by them".[174] In March 1933, he was a co-signatory to a letter in The Manchester Guardian protesting at the continuing misrepresentation of Soviet achievements: "No lie is too fantastic, no slander is too stale ... for employment by the more reckless elements of the British press."[170]

Shaw's admiration for Mussolini and Stalin demonstrated his growing belief that dictatorship was the only viable political arrangement. When the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in January 1933, Shaw described Hitler as "a very remarkable man, a very able man",[175] and professed himself proud to be the only writer in England who was "scrupulously polite and just to Hitler";[176][n 22] though his principal admiration was for Stalin, whose regime he championed uncritically throughout the decade.[174] Shaw saw the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact as a triumph for Stalin who, he said, now had Hitler under his thumb.[179]

Shaw's first play of the decade was Too True to Be Good, written in 1931 and premiered in Boston in February 1932. The reception was unenthusiastic. Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times commenting that Shaw had "yielded to the impulse to write without having a subject", judged the play a "rambling and indifferently tedious conversation". The correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune said that most of the play was "discourse, unbelievably long lectures" and that although the audience enjoyed the play it was bewildered by it.[180]

During the decade Shaw travelled widely and frequently. Most of his journeys were with Charlotte; she enjoyed voyages on ocean liners, and he found peace to write during the long spells at sea.[181] Shaw met an enthusiastic welcome in South Africa in 1932, despite his strong remarks about the racial divisions of the country.[182] In December 1932 the couple embarked on a round-the-world cruise. In March 1933 they arrived at San Francisco, to begin Shaw's first visit to the US. He had earlier refused to go to "that awful country, that uncivilized place", "unfit to govern itself ... illiberal, superstitious, crude, violent, anarchic and arbitrary".[181] He visited Hollywood, with which he was unimpressed, and New York, where he lectured to a capacity audience in the Metropolitan Opera House.[183] Harried by the intrusive attentions of the press, Shaw was glad when his ship sailed from New York harbour.[184] New Zealand, which he and Charlotte visited the following year, struck him as "the best country I've been in"; he urged its people to be more confident and loosen their dependence on trade with Britain.[185] He used the weeks at sea to complete two plays—The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles and The Six of Calais—and begin work on a third, The Millionairess.[186]

Despite his contempt for Hollywood and its aesthetic values, Shaw was enthusiastic about cinema, and in the middle of the decade wrote screenplays for prospective film versions of Pygmalion and Saint Joan.[187][188] The latter was never made, but Shaw entrusted the rights to the former to the unknown Gabriel Pascal, who produced it at Pinewood Studios in 1938. Shaw was determined that Hollywood should have nothing to do with the film, but was powerless to keep it from winning one Academy Award ("Oscar"); he described his award for "best-written screenplay" as an insult, coming from such a source.[189][n 23] He became the first person to have been awarded both a Nobel Prize and an Oscar.[192] In a 1993 study of the Oscars, Anthony Holden observes that Pygmalion was soon spoken of as having "lifted movie-making from illiteracy to literacy".[193]

Shaw's final plays of the 1930s were Cymbeline Refinished (1936), Geneva (1936) and In Good King Charles's Golden Days (1939). The first, a fantasy reworking of Shakespeare, made little impression, but the second, a satire on European dictators, attracted more notice, much of it unfavourable.[194] In particular, Shaw's parody of Hitler as "Herr Battler" was considered mild, almost sympathetic.[177][179] The third play, an historical conversation piece first seen at Malvern, ran briefly in London in May 1940.[195] James Agate commented that the play contained nothing to which even the most conservative audiences could take exception, and though it was long and lacking in dramatic action only "witless and idle" theatregoers would object.[195] After their first runs none of the three plays were seen again in the West End during Shaw's lifetime.[196]

Towards the end of the decade, both Shaws began to suffer ill health. Charlotte was increasingly incapacitated by Paget's disease of bone, and he developed pernicious anaemia. His treatment, involving injections of concentrated animal liver, was successful, but this breach of his vegetarian creed distressed him and brought down condemnation from militant vegetarians.[197]

Second World War and final years

Although Shaw's works since The Apple Cart had been received without great enthusiasm, his earlier plays were revived in the West End throughout the Second World War, starring such actors as Edith Evans, John Gielgud, Deborah Kerr and Robert Donat.[198] In 1944 nine Shaw plays were staged in London, including Arms and the Man with Ralph Richardson, Laurence Olivier, Sybil Thorndike and Margaret Leighton in the leading roles. Two touring companies took his plays all round Britain.[199] The revival in his popularity did not tempt Shaw to write a new play, and he concentrated on prolific journalism.[200] A second Shaw film produced by Pascal, Major Barbara (1941), was less successful both artistically and commercially than Pygmalion, partly because of Pascal's insistence on directing, to which he was unsuited.[201]

"The rest of Shaw's life was quiet and solitary. The loss of his wife was more profoundly felt than he had ever imagined any loss could be: for he prided himself on a stoical fortitude in all loss and misfortune."

St John Ervine on Shaw, 1959[2]

Following the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939 and the rapid conquest of Poland, Shaw was accused of defeatism when, in a New Statesman article, he declared the war over and demanded a peace conference.[202] Nevertheless, when he became convinced that a negotiated peace was impossible, he publicly urged the neutral United States to join the fight.[201] The London blitz of 1940–41 led the Shaws, both in their mid-eighties, to live full-time at Ayot St Lawrence. Even there they were not immune from enemy air raids, and stayed on occasion with Nancy Astor at her country house, Cliveden.[203] In 1943, the worst of the London bombing over, the Shaws moved back to Whitehall Court, where medical help for Charlotte was more easily arranged. Her condition deteriorated, and she died in September.[203]

Shaw's final political treatise, Everybody's Political What's What, was published in 1944. Holroyd describes this as "a rambling narrative ... that repeats ideas he had given better elsewhere and then repeats itself".[204] The book sold well—85,000 copies by the end of the year.[204] After Hitler's suicide in May 1945, Shaw approved of the formal condolences offered by the Irish Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, at the German embassy in Dublin.[205] Shaw disapproved of the postwar trials of the defeated German leaders, as an act of self-righteousness: "We are all potential criminals".[206]

Pascal was given a third opportunity to film Shaw's work with Caesar and Cleopatra (1945). It cost three times its original budget and was rated "the biggest financial failure in the history of British cinema".[207] The film was poorly received by British critics, although American reviews were friendlier. Shaw thought its lavishness nullified the drama, and he considered the film "a poor imitation of Cecil B. de Mille".[208]

In 1946, the year of Shaw's ninetieth birthday, he accepted the freedom of Dublin and became the first honorary freeman of the borough of St Pancras, London.[2] In the same year the British government asked Shaw informally whether he would accept the Order of Merit. He declined, believing that an author's merit could only be determined by the posthumous verdict of history.[209][n 24] 1946 saw the publication, as The Crime of Imprisonment, of the preface Shaw had written 20 years previously to a study of prison conditions. It was widely praised; a reviewer in the American Journal of Public Health considered it essential reading for any student of the American criminal justice system.[210]

Shaw continued to write into his nineties. His last plays were Buoyant Billions (1947), his final full-length work; Farfetched Fables (1948) a set of six short plays revisiting several of his earlier themes such as evolution; a comic play for puppets, Shakes versus Shav (1949), a ten-minute piece in which Shakespeare and Shaw trade insults;[211] and Why She Would Not (1950), which Shaw described as "a little comedy", written in one week shortly before his ninety-fourth birthday.[212]

During his later years, Shaw enjoyed tending the gardens at Shaw's Corner. He died at the age of 94 of renal failure precipitated by injuries incurred when falling while pruning a tree.[212] He was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 6 November 1950. His ashes, mixed with those of Charlotte, were scattered along footpaths and around the statue of Saint Joan in their garden.[213][214]

Remove ads

Works

Summarize

Perspective

Plays

Shaw published a collected edition of his plays in 1934, comprising forty-two works.[215] He wrote a further twelve in the remaining sixteen years of his life, mostly one-act pieces. Including eight earlier plays that he chose to omit from his published works, the total is sixty-two.[n 25]

Early works

1890s

Full-length plays

- Widowers' Houses

- The Philanderer

- Mrs Warren's Profession

- Arms and the Man

- Candida

- You Never Can Tell

- Three Plays for Puritans, comprising:

Adaptation

Short play

Shaw's first three full-length plays dealt with social issues. He later grouped them as "Plays Unpleasant".[216] Widowers' Houses (1892) concerns the landlords of slum properties, and introduces the first of Shaw's New Women—a recurring feature of later plays.[217] The Philanderer (1893) develops the theme of the New Woman, draws on Ibsen, and has elements of Shaw's personal relationships, the character of Julia being based on Jenny Patterson.[218] In a 2003 study Judith Evans describes Mrs Warren's Profession (1893) as "undoubtedly the most challenging" of the three Plays Unpleasant, taking Mrs Warren's profession—prostitute and, later, brothel-owner—as a metaphor for a prostituted society.[219]

Shaw followed the first trilogy with a second, published as "Plays Pleasant".[216] Arms and the Man (1894) conceals beneath a mock-Ruritanian comic romance a Fabian parable contrasting impractical idealism with pragmatic socialism.[220] The central theme of Candida (1894) is a woman's choice between two men; the play contrasts the outlook and aspirations of a Christian Socialist and a poetic idealist.[221] The third of the Pleasant group, You Never Can Tell (1896), portrays social mobility, and the gap between generations, particularly in how they approach social relations in general and mating in particular.[222]

The Three Plays for Puritans—comprising The Devil's Disciple (1896), Caesar and Cleopatra (1898) and Captain Brassbound's Conversion (1899)—all centre on questions of empire and imperialism, a major topic of political discourse in the 1890s.[223] The three are set, respectively, in 1770s America, Ancient Egypt, and 1890s Morocco.[224] The Gadfly, an adaptation of the popular novel by Ethel Voynich, was unfinished and unperformed.[225] The Man of Destiny (1895) is a short curtain raiser about Napoleon.[226]

1900–1909

1900–1909

Full-length plays

- Man and Superman

- John Bull's Other Island

- Major Barbara

- The Doctor's Dilemma

- Getting Married

- Misalliance

Short plays

Shaw's major plays of the first decade of the twentieth century address individual social, political or ethical issues. Man and Superman (1902) stands apart from the others in both its subject and its treatment, giving Shaw's interpretation of creative evolution in a combination of drama and associated printed text.[227] The Admirable Bashville (1901), a blank verse dramatisation of Shaw's novel Cashel Byron's Profession, focuses on the imperial relationship between Britain and Africa.[228] John Bull's Other Island (1904), comically depicting the prevailing relationship between Britain and Ireland, was popular at the time but fell out of the general repertoire in later years.[229] Major Barbara (1905) presents ethical questions in an unconventional way, confounding expectations that in the depiction of an armaments manufacturer on the one hand and the Salvation Army on the other the moral high ground must invariably be held by the latter.[230] The Doctor's Dilemma (1906), a play about medical ethics and moral choices in allocating scarce treatment, was described by Shaw as a tragedy.[231] With a reputation for presenting characters who did not resemble real flesh and blood,[232] he was challenged by Archer to present an on-stage death, and here did so, with a deathbed scene for the anti-hero.[233][234]

Getting Married (1908) and Misalliance (1909)—the latter seen by Judith Evans as a companion piece to the former—are both in what Shaw called his "disquisitionary" vein, with the emphasis on discussion of ideas rather than on dramatic events or vivid characterisation.[235] Shaw wrote seven short plays during the decade; they are all comedies, ranging from the deliberately absurd Passion, Poison, and Petrifaction (1905) to the satirical Press Cuttings (1909).[236]

1910–1919

1910–1919

Full-length plays

Short plays

In the decade from 1910 to the aftermath of the First World War Shaw wrote four full-length plays, the third and fourth of which are among his most frequently staged works.[237] Fanny's First Play (1911) continues his earlier examinations of middle-class British society from a Fabian viewpoint, with additional touches of melodrama and an epilogue in which theatre critics discuss the play.[77] Androcles and the Lion (1912), which Shaw began writing as a play for children, became a study of the nature of religion and how to put Christian precepts into practice.[238] Pygmalion (1912) is a Shavian study of language and speech and their importance in society and in personal relationships. To correct the impression left by the original performers that the play portrayed a romantic relationship between the two main characters Shaw rewrote the ending to make it clear that the heroine will marry another, minor character.[239][n 26] Shaw's only full-length play from the war years is Heartbreak House (1917), which in his words depicts "cultured, leisured Europe before the war" drifting towards disaster.[241] Shaw named Shakespeare (King Lear) and Chekhov (The Cherry Orchard) as important influences on the piece, and critics have found elements drawing on Congreve (The Way of the World) and Ibsen (The Master Builder).[241][242]

The short plays range from genial historical drama in The Dark Lady of the Sonnets and Great Catherine (1910 and 1913) to a study of polygamy in Overruled; three satirical works about the war (The Inca of Perusalem, O'Flaherty V.C. and Augustus Does His Bit, 1915–16); a piece that Shaw called "utter nonsense" (The Music Cure, 1914) and a brief sketch about a "Bolshevik empress" (Annajanska, 1917).[243]

1920–1950

1920–1950

Full-length plays

- Back to Methuselah

- Saint Joan

- The Apple Cart

- Too True to Be Good

- On the Rocks

- The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles

- The Millionairess

- Geneva

- In Good King Charles's Golden Days

- Buoyant Billions

Short plays

Saint Joan (1923) drew widespread praise both for Shaw and for Sybil Thorndike, for whom he wrote the title role and who created the part in Britain.[244] In the view of the commentator Nicholas Grene, Shaw's Joan, a "no-nonsense mystic, Protestant and nationalist before her time" is among the 20th century's classic leading female roles.[240] The Apple Cart (1929) was Shaw's last popular success.[245] He gave both that play and its successor, Too True to Be Good (1931), the subtitle "A political extravaganza", although the two works differ greatly in their themes; the first presents the politics of a nation (with a brief royal love-scene as an interlude) and the second, in Judith Evans's words, "is concerned with the social mores of the individual, and is nebulous."[246] Shaw's plays of the 1930s were written in the shadow of worsening national and international political events. Once again, with On the Rocks (1933) and The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles (1934), a political comedy with a clear plot was followed by an introspective drama. The first play portrays a British prime minister considering, but finally rejecting, the establishment of a dictatorship; the second is concerned with polygamy and eugenics and ends with the Day of Judgement.[247]

The Millionairess (1934) is a farcical depiction of the commercial and social affairs of a successful businesswoman. Geneva (1936) lampoons the feebleness of the League of Nations compared with the dictators of Europe. In Good King Charles's Golden Days (1939), described by Weintraub as a warm, discursive high comedy, also depicts authoritarianism, but less satirically than Geneva.[6] As in earlier decades, the shorter plays were generally comedies, some historical and others addressing various political and social preoccupations of the author. Ervine writes of Shaw's later work that although it was still "astonishingly vigorous and vivacious" it showed unmistakable signs of his age. "The best of his work in this period, however, was full of wisdom and the beauty of mind often displayed by old men who keep their wits about them."[2]

Music and drama reviews

Music

Shaw's collected musical criticism, published in three volumes, runs to more than 2,700 pages.[248] It covers the British musical scene from 1876 to 1950, but the core of the collection dates from his six years as music critic of The Star and The World in the late 1880s and early 1890s. In his view music criticism should be interesting to everyone rather than just the musical élite, and he wrote for the non-specialist, avoiding technical jargon—"Mesopotamian words like 'the dominant of D major'".[n 27] He was fiercely partisan in his columns, promoting the music of Wagner and decrying that of Brahms and those British composers such as Stanford and Parry whom he saw as Brahmsian.[66][250] He campaigned against the prevailing fashion for performances of Handel oratorios with huge amateur choirs and inflated orchestration, calling for "a chorus of twenty capable artists".[251] He railed against opera productions unrealistically staged or sung in languages the audience did not speak.[252]

Drama

In Shaw's view, the London theatres of the 1890s presented too many revivals of old plays and not enough new work. He campaigned against "melodrama, sentimentality, stereotypes and worn-out conventions".[253] As a music critic he had frequently been able to concentrate on analysing new works, but in the theatre he was often obliged to fall back on discussing how various performers tackled well-known plays. In a study of Shaw's work as a theatre critic, E. J. West writes that Shaw "ceaselessly compared and contrasted artists in interpretation and in technique". Shaw contributed more than 150 articles as theatre critic for The Saturday Review, in which he assessed more than 212 productions.[254] He championed Ibsen's plays when many theatregoers regarded them as outrageous, and his 1891 book Quintessence of Ibsenism remained a classic throughout the twentieth century.[255] Of contemporary dramatists writing for the West End stage he rated Oscar Wilde above the rest: "... our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audience, with the whole theatre".[256] Shaw's collected criticisms were published as Our Theatres in the Nineties in 1932.[257]

Shaw maintained a provocative and frequently self-contradictory attitude to Shakespeare (whose name he insisted on spelling "Shakespear").[258] Many found him difficult to take seriously on the subject; Duff Cooper observed that by attacking Shakespeare, "it is Shaw who appears a ridiculous pigmy shaking his fist at a mountain."[259] Shaw was, nevertheless, a knowledgeable Shakespearian, and in an article in which he wrote, "With the single exception of Homer, there is no eminent writer, not even Sir Walter Scott, whom I can despise so entirely as I despise Shakespear when I measure my mind against his," he also said, "But I am bound to add that I pity the man who cannot enjoy Shakespear. He has outlasted thousands of abler thinkers, and will outlast a thousand more".[258] Shaw had two regular targets for his more extreme comments about Shakespeare: undiscriminating "Bardolaters", and actors and directors who presented insensitively cut texts in over-elaborate productions.[260][n 28] He was continually drawn back to Shakespeare, and wrote three plays with Shakespearean themes: The Dark Lady of the Sonnets, Cymbeline Refinished and Shakes versus Shav.[264] In a 2001 analysis of Shaw's Shakespearian criticisms, Robert Pierce concludes that Shaw, who was no academic, saw Shakespeare's plays—like all theatre—from an author's practical point of view: "Shaw helps us to get away from the Romantics' picture of Shakespeare as a titanic genius, one whose art cannot be analyzed or connected with the mundane considerations of theatrical conditions and profit and loss, or with a specific staging and cast of actors."[265]

Political and social writings

Shaw's political and social commentaries were published variously in Fabian tracts, in essays, in two full-length books, in innumerable newspaper and journal articles and in prefaces to his plays. The majority of Shaw's Fabian tracts were published anonymously, representing the voice of the society rather than of Shaw, although the society's secretary Edward Pease later confirmed Shaw's authorship.[46] According to Holroyd, the business of the early Fabians, mainly under the influence of Shaw, was to "alter history by rewriting it".[266] Shaw's talent as a pamphleteer was put to immediate use in the production of the society's manifesto—after which, says Holroyd, he was never again so succinct.[266]

After the turn of the twentieth century, Shaw increasingly propagated his ideas through the medium of his plays. An early critic, writing in 1904, observed that Shaw's dramas provided "a pleasant means" of proselytising his socialism, adding that "Mr Shaw's views are to be sought especially in the prefaces to his plays".[267] After loosening his ties with the Fabian movement in 1911, Shaw's writings were more personal and often provocative; his response to the furore following the issue of Common Sense About the War in 1914, was to prepare a sequel, More Common Sense About the War. In this, he denounced the pacifist line espoused by Ramsay MacDonald and other socialist leaders, and proclaimed his readiness to shoot all pacifists rather than cede them power and influence.[268] On the advice of Beatrice Webb, this pamphlet remained unpublished.[269]

The Intelligent Woman's Guide, Shaw's main political treatise of the 1920s, attracted both admiration and criticism. MacDonald considered it the world's most important book since the Bible;[270] Harold Laski thought its arguments outdated and lacking in concern for individual freedoms.[163][n 29] Shaw's increasing flirtation with dictatorial methods is evident in many of his subsequent pronouncements. A New York Times report dated 10 December 1933 quoted a recent Fabian Society lecture in which Shaw had praised Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin: "[T]hey are trying to get something done, [and] are adopting methods by which it is possible to get something done".[271] As late as the Second World War, in Everybody's Political What's What, Shaw blamed the Allies' "abuse" of their 1918 victory for the rise of Hitler, and hoped that, after defeat, the Führer would escape retribution "to enjoy a comfortable retirement in Ireland or some other neutral country".[272] These sentiments, according to the Irish philosopher-poet Thomas Duddy, "rendered much of the Shavian outlook passé and contemptible".[273]

"Creative evolution", Shaw's version of the new science of eugenics, became an increasing theme in his political writing after 1900. He introduced his theories in The Revolutionist's Handbook (1903), an appendix to Man and Superman, and developed them further during the 1920s in Back to Methuselah. A 1946 Life magazine article observed that Shaw had "always tended to look at people more as a biologist than as an artist".[274] By 1933, in the preface to On the Rocks, he was writing that "if we desire a certain type of civilization and culture we must exterminate the sort of people who do not fit into it";[275] critical opinion is divided on whether this was intended as irony.[174][n 30] In an article in the American magazine Liberty in September 1938, Shaw included the statement: "There are many people in the world who ought to be liquidated".[274] Many commentators assumed that such comments were intended as a joke, although in the worst possible taste.[277] Otherwise, Life magazine concluded, "this silliness can be classed with his more innocent bad guesses".[274][n 31]

Fiction

Shaw's fiction-writing was largely confined to the five unsuccessful novels written in the period 1879–1885. Immaturity (1879) is a semi-autobiographical portrayal of mid-Victorian England, Shaw's "own David Copperfield" according to Weintraub.[6] The Irrational Knot (1880) is a critique of conventional marriage, in which Weintraub finds the characterisations lifeless, "hardly more than animated theories".[6] Shaw was pleased with his third novel, Love Among the Artists (1881), feeling that it marked a turning point in his development as a thinker, although he had no more success with it than with its predecessors.[278] Cashel Byron's Profession (1882) is, says Weintraub, an indictment of society which anticipates Shaw's first full-length play, Mrs Warren's Profession.[6] Shaw later explained that he had intended An Unsocial Socialist as the first section of a monumental depiction of the downfall of capitalism. Gareth Griffith, in a study of Shaw's political thought, sees the novel as an interesting record of conditions, both in society at large and in the nascent socialist movement of the 1880s.[279]

Shaw's only subsequent fiction of any substance was his 1932 novella The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God, written during a visit to South Africa in 1932. The eponymous girl, intelligent, inquisitive, and converted to Christianity by insubstantial missionary teaching, sets out to find God, on a journey that after many adventures and encounters, leads her to a secular conclusion.[280] The story, on publication, offended some Christians and was banned in Ireland by the Board of Censors.[281]

Letters and diaries

Shaw was a prolific correspondent throughout his life. His letters, edited by Dan H. Laurence, were published between 1965 and 1988.[282] Shaw once estimated his letters would occupy twenty volumes; Laurence commented that, unedited, they would fill many more.[283] Shaw wrote more than a quarter of a million letters, of which about ten per cent have survived; 2,653 letters are printed in Laurence's four volumes.[284] Among Shaw's many regular correspondents were his childhood friend Edward McNulty; his theatrical colleagues (and amitiés amoureuses) Mrs Patrick Campbell and Ellen Terry; writers including Lord Alfred Douglas, H. G. Wells and G. K. Chesterton; the boxer Gene Tunney; the nun Laurentia McLachlan; and the art expert Sydney Cockerell.[285][n 32] In 2007 a 316-page volume consisting entirely of Shaw's letters to The Times was published.[286]

Shaw's diaries for 1885–1897, edited by Weintraub, were published in two volumes, with a total of 1,241 pages, in 1986. Reviewing them, the Shaw scholar Fred Crawford wrote: "Although the primary interest for Shavians is the material that supplements what we already know about Shaw's life and work, the diaries are also valuable as a historical and sociological document of English life at the end of the Victorian age." After 1897, pressure of other writing led Shaw to give up keeping a diary.[287]

Miscellaneous and autobiographical

Through his journalism, pamphlets and occasional longer works, Shaw wrote on many subjects. His range of interest and enquiry included vivisection, vegetarianism, religion, language, cinema and photography,[n 33] on all of which he wrote and spoke copiously. Collections of his writings on these and other subjects were published, mainly after his death, together with volumes of "wit and wisdom" and general journalism.[286]

Despite the many books written about him (Holroyd counts 80 by 1939)[289] Shaw's autobiographical output, apart from his diaries, was relatively slight. He gave interviews to newspapers—"GBS Confesses", to The Daily Mail in 1904 is an example[290]—and provided sketches to would-be biographers whose work was rejected by Shaw and never published.[291] In 1939 Shaw drew on these materials to produce Shaw Gives Himself Away, a miscellany which, a year before his death, he revised and republished as Sixteen Self Sketches (there were seventeen). He made it clear to his publishers that this slim book was in no sense a full autobiography.[292]

Remove ads

Beliefs and opinions

Summarize

Perspective

Shaw was a poseur and a puritan; he was similarly a bourgeois and an antibourgeois writer, working for Hearst and posterity; his didacticism is entertaining and his pranks are purposeful; he supports socialism and is tempted by fascism.

—Leonard Feinberg, The Satirist (2006)[293]

Throughout his lifetime Shaw professed many beliefs, often contradictory. This inconsistency was partly an intentional provocation—the Spanish scholar-statesman Salvador de Madariaga describes Shaw as "a pole of negative electricity set in a people of positive electricity".[294] In one area at least Shaw was constant: in his lifelong refusal to follow normal English forms of spelling and punctuation. He favoured archaic spellings such as "shew" for "show"; he dropped the "u" in words like "honour" and "favour"; and wherever possible he rejected the apostrophe in contractions such as "won't" or "that's".[295] In his will, Shaw ordered that, after some specified legacies, his remaining assets were to form a trust to pay for fundamental reform of the English alphabet into a phonetic version of forty letters.[6] Though Shaw's intentions were clear, his drafting was flawed, and the courts initially ruled the intended trust void. A later out-of-court agreement provided a sum of £8,300 for spelling reform; the bulk of his fortune went to the residuary legatees—the British Museum, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the National Gallery of Ireland.[296][n 34] Most of the £8,300 went on a special phonetic edition of Androcles and the Lion in the Shavian alphabet, published in 1962 to a largely indifferent reception.[299]

Shaw's views on religion and Christianity were less consistent. Having in his youth proclaimed himself an atheist, in middle age he explained this as a reaction against the Old Testament image of a vengeful Jehovah. By the early twentieth century, he termed himself a "mystic", although Gary Sloan, in an essay on Shaw's beliefs, disputes his credentials as such.[300] In 1913 Shaw declared that he was not religious "in the sectarian sense", aligning himself with Jesus as "a person of no religion".[301] In the preface (1915) to Androcles and the Lion, Shaw asks "Why not give Christianity a chance?" contending that Britain's social order resulted from the continuing choice of Barabbas over Christ.[301] In a broadcast just before the Second World War, Shaw invoked the Sermon on the Mount, "a very moving exhortation, and it gives you one first-rate tip, which is to do good to those who despitefully use you and persecute you".[300] In his will, Shaw stated that his "religious convictions and scientific views cannot at present be more specifically defined than as those of a believer in creative revolution".[302] He requested that no one should imply that he accepted the beliefs of any specific religious organisation, and that no memorial to him should "take the form of a cross or any other instrument of torture or symbol of blood sacrifice".[302]

Shaw espoused racial equality, and inter-marriage between people of different races.[303] Despite his expressed wish to be fair to Hitler,[176] he called anti-Semitism "the hatred of the lazy, ignorant fat-headed Gentile for the pertinacious Jew who, schooled by adversity to use his brains to the utmost, outdoes him in business".[304] In The Jewish Chronicle he wrote in 1932, "In every country you can find rabid people who have a phobia against Jews, Jesuits, Armenians, Negroes, Freemasons, Irishmen, or simply foreigners as such. Political parties are not above exploiting these fears and jealousies."[305]

In 1903 Shaw joined in a controversy about vaccination against smallpox. He called vaccination "a peculiarly filthy piece of witchcraft";[306] in his view immunisation campaigns were a cheap and inadequate substitute for a decent programme of housing for the poor, which would, he declared, be the means of eradicating smallpox and other infectious diseases.[29] Less contentiously, Shaw was keenly interested in transport; Laurence observed in 1992 a need for a published study of Shaw's interest in "bicycling, motorbikes, automobiles, and planes, climaxing in his joining the Interplanetary Society in his nineties".[307] Shaw published articles on travel, took photographs of his journeys, and submitted notes to the Royal Automobile Club.[307]

Shaw strove throughout his adult life to be referred to as "Bernard Shaw" rather than "George Bernard Shaw", but confused matters by continuing to use his full initials—G.B.S.—as a by-line, and often signed himself "G. Bernard Shaw".[308] He left instructions in his will that his executor (the Public Trustee) was to license publication of his works only under the name Bernard Shaw.[6] Shaw scholars including Ervine, Judith Evans, Holroyd, Laurence and Weintraub, and many publishers have respected Shaw's preference, although the Cambridge University Press was among the exceptions with its 1988 Cambridge Companion to George Bernard Shaw.[257]

Remove ads

Legacy and influence

Summarize

Perspective

Theatrical

Shaw, arguably the most important English-language playwright after Shakespeare, produced an immense oeuvre, of which at least half a dozen plays remain part of the world repertoire. ... Academically unfashionable, of limited influence even in areas such as Irish drama and British political theatre where influence might be expected, Shaw's unique and unmistakable plays keep escaping from the safely dated category of period piece to which they have often been consigned.

Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre (2003)[240]

Shaw did not found a school of dramatists as such, but Crawford asserts that today "we recognise [him] as second only to Shakespeare in the British theatrical tradition ... the proponent of the theater of ideas" who struck a death-blow to 19th-century melodrama.[309] According to Laurence, Shaw pioneered "intelligent" theatre, in which the audience was required to think, thereby paving the way for the new breeds of twentieth-century playwrights from Galsworthy to Pinter.[310]

Crawford lists numerous playwrights whose work owes something to that of Shaw. Among those active in Shaw's lifetime he includes Noël Coward, who based his early comedy The Young Idea on You Never Can Tell and continued to draw on the older man's works in later plays.[311][312] T. S. Eliot, by no means an admirer of Shaw, admitted that the epilogue of Murder in the Cathedral, in which Becket's slayers explain their actions to the audience, might have been influenced by Saint Joan.[313] The critic Eric Bentley comments that Eliot's later play The Confidential Clerk "had all the earmarks of Shavianism ... without the merits of the real Bernard Shaw".[314] Among more recent British dramatists, Crawford marks Tom Stoppard as "the most Shavian of contemporary playwrights";[315] Shaw's "serious farce" is continued in the works of Stoppard's contemporaries Alan Ayckbourn, Henry Livings and Peter Nichols.[316]

Shaw's influence crossed the Atlantic at an early stage. Bernard Dukore notes that he was successful as a dramatist in America ten years before achieving comparable success in Britain.[317] Among many American writers professing a direct debt to Shaw, Eugene O'Neill became an admirer at the age of seventeen, after reading The Quintessence of Ibsenism.[318] Other Shaw-influenced American playwrights mentioned by Dukore are Elmer Rice, for whom Shaw "opened doors, turned on lights, and expanded horizons";[319] William Saroyan, who empathised with Shaw as "the embattled individualist against the philistines";[320] and S. N. Behrman, who was inspired to write for the theatre after attending a performance of Caesar and Cleopatra: "I thought it would be agreeable to write plays like that".[321]

Assessing Shaw's reputation in a 1976 critical study, T. F. Evans described Shaw as unchallenged in his lifetime and since as the leading English-language dramatist of the (twentieth) century, and as a master of prose style.[322] The following year, in a contrary assessment, the playwright John Osborne castigated The Guardian's theatre critic Michael Billington for referring to Shaw as "the greatest British dramatist since Shakespeare". Osborne responded that Shaw "is the most fraudulent, inept writer of Victorian melodramas ever to gull a timid critic or fool a dull public".[323] Despite this hostility, Crawford sees the influence of Shaw in some of Osborne's plays, and concludes that though the latter's work is neither imitative nor derivative, these affinities are sufficient to classify Osborne as an inheritor of Shaw.[315]

In a 1983 study, R. J. Kaufmann suggests that Shaw was a key forerunner—"godfather, if not actually finicky paterfamilias"—of the Theatre of the Absurd.[324] Two further aspects of Shaw's theatrical legacy are noted by Crawford: his opposition to stage censorship, which was finally ended in 1968, and his efforts which extended over many years to establish a National Theatre.[316] Shaw's short 1910 play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets, in which Shakespeare pleads with Queen Elizabeth I for the endowment of a state theatre, was part of this campaign.[325]

Writing in The New Statesman in 2012 Daniel Janes commented that Shaw's reputation had declined by the time of his 150th anniversary in 2006 but had recovered considerably. In Janes's view, the many current revivals of Shaw's major works showed the playwright's "almost unlimited relevance to our times".[326] In the same year, Mark Lawson wrote in The Guardian that Shaw's moral concerns engaged present-day audiences, and made him—like his model, Ibsen—one of the most popular playwrights in contemporary British theatre.[327]

The Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada is the second largest repertory theatre company in North America. It produces plays by or written during the lifetime of Shaw as well as some contemporary works.[328] The Gingold Theatrical Group, founded in 2006, presents works by Shaw and others in New York City that feature the humanitarian ideals that his work promoted.[329] It became the first theatre group to present all of Shaw's stage work through its monthly concert series Project Shaw.[330]

General

In the 1940s the author Harold Nicolson advised the National Trust not to accept the bequest of Shaw's Corner, predicting that Shaw would be totally forgotten within fifty years.[331] In the event, Shaw's broad cultural legacy, embodied in the widely used term "Shavian", has endured and is nurtured by Shaw Societies in various parts of the world. The original society was founded in London in 1941 and survives; it organises meetings and events, and publishes a regular bulletin The Shavian. The Shaw Society of America began in June 1950; it foundered in the 1970s but its journal, adopted by Penn State University Press, continued to be published as Shaw: The Annual of Bernard Shaw Studies until 2004. A second American organisation, founded in 1951 as "The Bernard Shaw Society", remains active as of 2016[update]. More recent societies have been established in Japan and India.[332]

Besides his collected music criticism, Shaw has left a varied musical legacy, not all of it of his choosing. Despite his dislike of having his work adapted for the musical theatre ("my plays set themselves to a verbal music of their own")[333] two of his plays were turned into musical comedies: Arms and the Man was the basis of The Chocolate Soldier in 1908, with music by Oscar Straus, and Pygmalion was adapted in 1956 as My Fair Lady with book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe.[66] Although he had a high regard for Elgar, Shaw turned down the composer's request for an opera libretto, but played a major part in persuading the BBC to commission Elgar's Third Symphony, and was the dedicatee of The Severn Suite (1930).[66][334]