Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia

Political party in the Czech Republic From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Czech: Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM) is a communist party[23] in the Czech Republic.[24] As of January 2025, KSČM had a membership of 16 843.[25] Sources variously describe the party as either left-wing[30] to far-left[37] on the political spectrum.[38] It is one of the few former ruling parties in post-Communist Central Eastern Europe to have not dropped the Communist title from its name, although it has changed its party program to adhere to laws adopted after 1989.[39][40] It was previously a member party of The Left group in the European Parliament,[41] and an observer member of the European Left Party,[42] but is now unaffiliated.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Czech. (February 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

For most of the first two decades after the Velvet Revolution, the party was politically isolated and accused of extremism, but later moved closer to the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD).[40] After the 2012 Czech regional elections, KSČM began governing in coalition with the ČSSD in 10 regions.[43] It has never been part of a governing coalition in the executive branch but provided parliamentary support to Andrej Babiš' Second Cabinet until April 2021. The party's youth organization was banned from 2006 to 2010,[40][44] and there have been calls from other parties to outlaw the main party.[45] Until 2013, it was the only political party in the Czech Republic printing its own newspaper, called Haló noviny.[46] The party's two cherry logo comes from the song Le Temps des cerises, a revolutionary song associated with the Paris Commune.[47]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The party was formed in 1989 by a congress of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), which decided to create a party for the territories of Bohemia and Moravia (including Czech Silesia), the areas that were to become the Czech Republic. The new party's organization was significantly more democratic and decentralized than the previous party, and gave local district branches of the party significant autonomy.[48]

In 1990, KSČ was reorganized as a federation of KSČM and the Communist Party of Slovakia (KSS). Later, KSS changed its name to the Party of the Democratic Left, and the federation dissolved in 1992. During the party's first congress, held in Olomouc in October 1990, party leader Jiří Svoboda attempted to reform the party into a democratic socialist one, proposing a democratic socialist program and changing the name to the transitional Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia: Party of Democratic Socialism.[49] Svoboda had to balance the criticisms of older, conservative communists, who made up a majority of the party's members, with the demands of an increasingly large and moderate bloc of members, led primarily by a group of young KSČM parliamentarians called the Democratic Left, who demanded the immediate social democratization of the party. Delegates approved the new program but rejected the name change.[39]

During 1991 and 1992, factional tensions increased, with the party's conservative, anti-revisionist wing increasingly vocal in criticizing Svoboda. There was an increase in popularity of the anti-revisionist Marxist–Leninist clubs amongst rank-and-file party members. On the party's other wing, the Democratic Left became increasingly critical of the slow pace of the reforms and began demanding a referendum of members to change the name. In December 1991, the Democratic Left split off and formed the short-lived Party of Democratic Labour. The referendum on changing the name was held in 1992, with 75.94% voting not to change the name.[39]

The party's second congress, held in Kladno in December 1992, showed the increasing popularity of the party's anti-revisionist wing. It passed resolutions reinterpreting the 1990 program as a "starting point" for KSČM, rather than a definitive statement of a post-communist program. Svoboda, who was hospitalized due to an attack by an anti-communist, could not attend the congress but was nevertheless overwhelmingly re-elected.[39] After the party's second congress in 1992, several groups split away. A group of post-communist delegates split off and merged with the Party of Democratic Labour to form the Party of the Democratic Left (SDL). Several independent left-wing members who had participated with KSČM in the 1992 electoral pact, which was called the Left Bloc, left the party to form the Left Bloc Party.[48] Both groups eventually merged into the Party of Democratic Socialism.[50]

In 1993, Svoboda attempted to expel the members of the "For Socialism" platform, a group in the party that wanted a restoration of the pre-1989 Communist regime;[51] however, with only the lukewarm support of KSČM's central committee, he briefly resigned. He withdrew his resignation after the central committee agreed to move the party's next congress forward to June 1993 to resolve the issues of its name and ideology.[48] At the 1993 congress, held in Prostějov, Svoboda's proposals were overwhelmingly rejected by two-thirds majorities. Svoboda did not seek re-election as chairman, and neocommunist Miroslav Grebeníček was elected chairman. Grebeníček and his supporters were critical of what they termed the inadequacies of the pre-1989 regime but supported the retention of the party's communist character and program. The members of the "For Socialism" platform were expelled at the congress, with the existence of platforms in the party being banned altogether, on the grounds that they gave too much influence to minority groups. Svoboda left the party.[48]

"Conservative elements within the KSČM" were described as dominating the party's May 2004 Congress.[52]

The expelled members of "For Socialism" formed the Party of Czechoslovak Communists, later renamed the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which was led by Miroslav Štěpán.[50] KSČM refuses to work with this group. The party was left on the sidelines for most of the first decade of the Czech Republic's existence. Václav Havel suspected KSČM was still an unreconstructed neo-Stalinist party and prevented it from having any influence during his presidency; however, the party provided the one-vote margin that elected Havel's successor Václav Klaus as president.[53] After a long-running battle with the Ministry of the Interior, the Communist Youth Union led by Milan Krajča, was dissolved in 2006 for allegedly endorsing in its program the replacement of private with collective ownership of the means of production.[44] The decision met with international protests.[54]

In November 2008, the Czech Senate asked the Supreme Administrative Court to dissolve KSČM because of its political program, which the Senate argued contradicted the Constitution of the Czech Republic. 30 out of the 38 senators who were present agreed to this request, and expressed the view that the party's program did not reject violence as a means of attaining power and adopted The Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx.[55] However, this was only a symbolic gesture, as according to the constitution only the cabinet may file a petition to the Supreme Administrative Court to dissolve a political party. For the first two decades after the end of communist rule in Czechoslovakia, the party was politically isolated. After the 2012 Czech regional elections, it started participating in coalitions with the Czech Social Democratic Party, forming part of the ruling coalition in 10 out of 13 regions.[43] From 2018 to 2021, KSČM provided parliamentary support to Andrej Babiš' second cabinet.[56][57]

After the party's poor performance in the 2021 Czech legislative election, in which KSČM failed to reach the 5% voting threshold and was excluded from representation in parliament for the first time in its history, Filip resigned as leader of the party.[58] On 23 October 2021, Member of European Parliament Kateřina Konečná was elected as leader.[59]

In 2025, the Czech government passed an amendment to the national criminal code that introduces up to five years of prison for anyone who "establishes, supports or promotes Nazi, communist, or other movements which demonstrably aim to suppress human rights and freedoms or incite racial, ethnic, national, religious or class-based hatred". KSČM condemned the law, describing it as an attempt "to push KSČM outside the law and intimidate critics of the current regime".[60] The amendment will come to force in 2026; it is not clear how the amendment will affect the party – in an interview with Novinky, constitutional lawyer Jan Kysela argued that while KSČM's existence might not be in danger, the law could result in legal actions against its members.[61]

Remove ads

Ideology

Summarize

Perspective

As a communist party and the successor of the former ruling Communist Party of Czechoslovakia,[63] its party platform promotes anti-capitalism[64] and socialism.[65][66] Unlike other communist parties in post-communist Europe, KSČM "refused to break away with its communist past and largely preserved its Marxist agenda".[67] The party is also described as national communist.[68] It is classified as a radical left party.[69] It holds Eurosceptic views in regards to the European Union,[73] and has been described as pro-Russian,[74] pro-Chinese,[75] left-authoritarian in that it "combines cultural conservativism with an economic left-wing stance",[18] nativist,[76] and left-conservative.[17] It is conservative on sociocultural matters.[77] The Green European Journal described it as "culturally conservative, Islamophobic, and anti-EU, with many pro-Russian and openly far-right personalities in its ranks."[21] Ideologically, the party is very similar to Slovak Smer and German BSW.[78] Political scientist Luke March also compares it to the Russian KPRF:

In particular, they are relatively weakly influenced by post-68 new left ideas or Eurocommunism, and some evidence of environmentalism in KSCM and KPRF platforms notwithstanding, these two parties remain far more socially conservative, materialist, and national-chauvinist than more reformist parties such as Rifondazione and even the PCF.[79]

The party's platform is considered to be based on key tenets of socialist ideology, as it supports the re-nationalization of the water, gas, electricity and transportation industries, the expansion of worker cooperatives, and the introduction of communally-owned firms based on the economic model of socialist Czechoslovakia. The party argues that everyone should have a guaranteed right to a job, receiving a salary that corresponds to how demanding the job is, and that the minimum wage should correspond to half the national average income. KSČM also promotes a system of non-profit hospitals and a single state-owned health insurance company. It says it would be willing to participate in non-socialist governments as long as its six demands are met: regular increases in both the minimum wage and pensions, expanding public ownership of water utilities, extraction of natural resources only by domestic companies, construction of communal housing, and abolishing patient fees in health care.[80]

Political scientist Maria Snegovaya wrote that "over the years, KSČM adopted a platform reminiscent of those used by populist right parties in other countries: protectionist on the economic dimension, Euroskeptic and nationalist on the sociocultural dimension". It rejects European integration as "capitalist" and "neoliberal", arguing that it is destructive to the living conditions of citizens and ignores social issues. KSČM is considered to be an anti-Western party, and opposes Czech membership of NATO on nationalist grounds, calling NATO "US- and Germany-dominated" and naming it, alongside the Lisbon Treaty, as "a threat to Czech state sovereignty that led to the exploitation of Czech interests by multinational capitalist forces". Party representatives also advocate for the legitimization of the Russian policy towards Ukraine, regarding Crimea as a Russian territory and opposing EU sanctions against Russia. In 2014, KSČM leader Vojtech Filip visited Russia, and party members served as election observers in the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic.[81]

Regarding the Gaza War, the KSČM "strongly condemns the ongoing aggression of the State of Israel against Lebanon, which follows a year of brutal Israeli aggression in the Palestinian Gaza Strip."[82] KSČM is considered "a staunch ally of China, both in domestic and international contexts." Since the 1990s, members of the party have been frequently visiting China on state-organized tours, and the KSČM also attended a conference on Chinese policies in Xinjiang organized by the Chinese Communist Party. The party criticizes the Czech government for its support of Taiwan and "aggressive and interventionist stance on China". It argues that the Czech Republic should instead recognize One China principle and also accuses 'US-funded NGOs' on shaping the Czech foreign policy.[83] Along with Russia and China, KSČM also expressed support for Cuba, Venezuela, and Belarus.[84]

The party has been described as embracing "a socially conservative and nationalist platform in the democratic era".[85] On the GAL-TAN (green/alternative/libertarian vs. traditional/authoritarian/nationalist) dimension used to measure sociocultural values, the KSČM is "a radical left party both in terms of its general positioning and economic stances, but characterised by holding traditional, authoritarian and nationalist (TAN) views."[86] It was described as illiberal, and its sociocultural views are considered to be as TAN as the ones of KDU-ČSL.[87] Jan Rovny of Sciences Po commented on the party: "Its socioeconomic program may be left-wing, but it is otherwise a nationalist, anti-immigrant, very conservative party."[88] According to historian Stanislav Holubec, the party's newspaper Haló noviny publishes "nationalistic, Stalinist, authoritarian and homophobic items".[89]

The party does not present an official stance on LGBT issues.[90] In 2014, 20 MPs from ODS, VV, LIDEM, ČSSD, TOP 09 and KSČM drafted an unsuccessful amendment to allow stepchild adoption within same-sex registered partnerships.[91] In June 2018, 46 MPs from ANO, ČSSD, the Pirate Party, STAN, TOP 09 and KSČM introduced a draft bill to abolish registered partnerships and introduce same-sex marriage.[92] However, the majority of KSČM MPs were opposed to same-sex marriage.[93] Political scientist Tomáš Novotný described the party's view on same-sex marriage as "rather negative",[94] while Balkan Insight wrote that the party is in "staunch opposition" to it.[95] KSČM does not consider gender equality to be a policy aim, and voted against the Antidiscrimination Bill.[96] The party also argues that immigrants are taking advantage of the Czech social system, including economic immigrants.[97] It denounced the EU migration quota system, describing the EU as a "dictatorship" and declaring that the Czechs are "not pupils of Brussels".[98]

After the election of Konečná as the leader of the party in 2021, KSČM "reinforced its image as a Eurosceptic, populist radical-left party, while increasingly shifting towards conservative and nationalist positions, particularly in its criticism of the European Union, migration, and LGBT policies". This was coupled with reinforcing its strongly pro-Russian position and the foundation of Stačilo!, where the party formed an alliance with nationalist-conservative parties which marked "a further departure from its left-wing roots." It is argued that KSČM underwent a "transformation towards a nationalist-populist party".[99] At the same time, while increasingly adopting traditionalist, authoritarian and nationalist stances on social issues, the party preserved its economically communist character.[99] Political scientist Michael Perottino argues that KSČM "clearly turned from red to “brown,” becoming less leftist than nationalist" and that the main traits of the party's ideology have become "sovereigntism and nationalism, pro-Russian positions at any cost, and the fight against NATO".[100]

Remove ads

Leaders

Electoral results

Summarize

Perspective

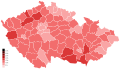

The voter base of KSČM is dominated by blue-collar workers and retired workers; it also preserves strong links to trade union activists, and 57% of its supporters are drawn from trade unions. About 20% of trade unions members are supporters of KSČM. The party's membership and voter structure shows a disproportional share of blue-collar workers, and working-class voters in general.[101] The party's voter base is predominantly those who are dissatisfied with the functioning of Czech democracy, distrust public institutions, or live in areas with high levels of unemployment and crime.[102] It is stronger among older than younger voters, with the majority of its membership over 60.[103] The party is also stronger in small and medium-sized towns than in big cities.[104]

Parliament

Chamber of Deputies

- Notes

- KSCM 1996

- KSCM 1998

- KSCM 2002

- KSCM 2006

- KSCM 2010

- KSCM 2013

- KSCM 2017

- KSCM 2021

Senate

European Parliament

Local councils

Regional councils

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads