Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ethics

Philosophical study of morality From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied ethics, and metaethics.

Normative ethics aims to find general principles that govern how people should act. Applied ethics examines concrete ethical problems in real-life situations, such as abortion, treatment of animals, and business practices. Metaethics explores the underlying assumptions and concepts of ethics. It asks whether there are objective moral facts, how moral knowledge is possible, and how moral judgments motivate people. Influential normative theories are consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics. According to consequentialists, an act is right if it leads to the best consequences. Deontologists focus on acts themselves, saying that they must adhere to duties, like telling the truth and keeping promises. Virtue ethics sees the manifestation of virtues, like courage and compassion, as the fundamental principle of morality.

Ethics is closely connected to value theory, which studies the nature and types of value, like the contrast between intrinsic and instrumental value. Moral psychology is a related empirical field and investigates psychological processes involved in morality, such as reasoning and the formation of character. Descriptive ethics describes the dominant moral codes and beliefs in different societies and considers their historical dimension.

The history of ethics started in the ancient period with the development of ethical principles and theories in ancient Egypt, India, China, and Greece. This period saw the emergence of ethical teachings associated with Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, and contributions of philosophers like Socrates and Aristotle. During the medieval period, ethical thought was strongly influenced by religious teachings. In the modern period, this focus shifted to a more secular approach concerned with moral experience, reasons for acting, and the consequences of actions. An influential development in the 20th century was the emergence of metaethics.

Remove ads

Definition

Summarize

Perspective

Ethics, also called moral philosophy, is the study of moral phenomena. It is one of the main branches of philosophy and investigates the nature of morality and the principles that govern the moral evaluation of conduct, character traits, and institutions. It examines what obligations people have, what behavior is right and wrong, and how to lead a good life. Some of its key questions are "How should one live?" and "What gives meaning to life?".[2] In contemporary philosophy, ethics is usually divided into normative ethics, applied ethics, and metaethics.[3]

Morality is about what people ought to do rather than what they actually do, what they want to do, or what social conventions require. As a rational and systematic field of inquiry, ethics studies practical reasons why people should act one way rather than another. Most ethical theories seek universal principles that express a general standpoint of what is objectively right and wrong.[4] In a slightly different sense, the term ethics can also refer to individual ethical theories in the form of a rational system of moral principles, such as Aristotelian ethics, and to a moral code that certain societies, social groups, or professions follow, as in Protestant work ethic and medical ethics.[5]

The English word ethics has its roots in the Ancient Greek word êthos (ἦθος), meaning 'character' and 'personal disposition'. This word gave rise to the Ancient Greek word ēthikós (ἠθικός), which was translated into Latin as ethica and entered the English language in the 15th century through the Old French term éthique.[6] The term morality originates in the Latin word moralis, meaning 'manners' and 'character'. It was introduced into the English language during the Middle English period through the Old French term moralité.[7]

The terms ethics and morality are usually used interchangeably but some philosophers distinguish between the two. According to one view, morality focuses on what moral obligations people have while ethics is broader and includes ideas about what is good and how to lead a meaningful life. Another difference is that codes of conduct in specific areas, such as business and environment, are usually termed ethics rather than morality, as in business ethics and environmental ethics.[8]

Remove ads

Normative ethics

Summarize

Perspective

Normative ethics is the philosophical study of ethical conduct and investigates the fundamental principles of morality. It aims to discover and justify general answers to questions like "How should one live?" and "How should people act?", usually in the form of universal or domain-independent principles that determine whether an act is right or wrong.[9] For example, given the particular impression that it is wrong to set a child on fire for fun, normative ethics aims to find more general principles that explain why this is the case, like the principle that one should not cause extreme suffering to the innocent, which may itself be explained in terms of a more general principle.[10] Many theories of normative ethics also aim to guide behavior by helping people make moral decisions.[11]

Theories in normative ethics state how people should act or what kind of behavior is correct. They do not aim to describe how people normally act, what moral beliefs ordinary people have, how these beliefs change over time, or what ethical codes are upheld in certain social groups. These topics belong to descriptive ethics and are studied in fields like anthropology, sociology, and history rather than normative ethics.[12]

Some systems of normative ethics arrive at a single principle covering all possible cases. Others encompass a small set of basic rules that address all or at least the most important moral considerations.[13] One difficulty for systems with several basic principles is that these principles may conflict with each other in some cases and lead to ethical dilemmas.[14]

Distinct theories in normative ethics suggest different principles as the foundation of morality. The three most influential schools of thought are consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics.[15] These schools are usually presented as exclusive alternatives, but depending on how they are defined, they can overlap and do not necessarily exclude one another.[16] In some cases, they differ in which acts they see as right or wrong. In other cases, they recommend the same course of action but provide different justifications for why it is right.[17]

Consequentialism

Consequentialism, also called teleological ethics,[18][a] says that morality depends on consequences. According to the most common view, an act is right if it brings the best future. This means that there is no alternative course of action that has better consequences.[20] A key aspect of consequentialist theories is that they provide a characterization of what is good and then define what is right in terms of what is good.[21] For example, classical utilitarianism says that pleasure is good and that the action leading to the most overall pleasure is right.[22] Consequentialism has been discussed indirectly since the formulation of classical utilitarianism in the late 18th century. A more explicit analysis of this view happened in the 20th century, when the term was coined by G. E. M. Anscombe.[23]

Consequentialists usually understand the consequences of an action in a very wide sense that includes the totality of its effects. This is based on the idea that actions make a difference in the world by bringing about a causal chain of events that would not have existed otherwise.[24] A core intuition behind consequentialism is that the future should be shaped to achieve the best possible outcome.[25]

The act itself is usually not seen as part of the consequences. This means that if an act has intrinsic value or disvalue, it is not included as a factor. Some consequentialists see this as a flaw, saying that all value-relevant factors need to be considered. They try to avoid this complication by including the act itself as part of the consequences. A related approach is to characterize consequentialism not in terms of consequences but in terms of outcome, with the outcome being defined as the act together with its consequences.[26]

Most forms of consequentialism are agent-neutral. This means that the value of consequences is assessed from a neutral perspective, that is, acts should have consequences that are good in general and not just good for the agent. It is controversial whether agent-relative moral theories, like ethical egoism, should be considered as types of consequentialism.[27]

Types

There are many different types of consequentialism. They differ based on what type of entity they evaluate, what consequences they take into consideration, and how they determine the value of consequences.[28] Most theories assess the moral value of acts. However, consequentialism can also be used to evaluate motives, character traits, rules, and policies.[29]

Many types assess the value of consequences based on whether they promote happiness or suffering. But there are also alternative evaluative principles, such as desire satisfaction, autonomy, freedom, knowledge, friendship, beauty, and self-perfection.[30] Some forms of consequentialism hold that there is only a single source of value.[31] The most prominent among them is classical utilitarianism, which states that the moral value of acts only depends on the pleasure and suffering they cause.[32] An alternative approach says that there are many different sources of value, which all contribute to one overall value.[31] Before the 20th century, consequentialists were only concerned with the total of value or the aggregate good. In the 20th century, alternative views were developed that additionally consider the distribution of value. One of them states that an equal distribution of goods is better than an unequal distribution even if the aggregate good is the same.[33]

There are disagreements about which consequences should be assessed. An important distinction is between act consequentialism and rule consequentialism. According to act consequentialism, the consequences of an act determine its moral value. This means that there is a direct relation between the consequences of an act and its moral value. Rule consequentialism, by contrast, holds that an act is right if it follows a certain set of rules. Rule consequentialism determines the best rules by considering their outcomes at a community level. People should follow the rules that lead to the best consequences when everyone in the community follows them. This implies that the relation between an act and its consequences is indirect. For example, if telling the truth is one of the best rules, then according to rule consequentialism, a person should tell the truth even in specific cases where lying would lead to better consequences.[34]

Another disagreement is between actual and expected consequentialism. According to the traditional view, only the actual consequences of an act affect its moral value. One difficulty of this view is that many consequences cannot be known in advance. This means that in some cases, even well-planned and intentioned acts are morally wrong if they inadvertently lead to negative outcomes. An alternative perspective states that what matters are not the actual consequences but the expected consequences. This view takes into account that when deciding what to do, people have to rely on their limited knowledge of the total consequences of their actions. According to this view, a course of action has positive moral value despite leading to an overall negative outcome if it had the highest expected value, for example, because the negative outcome could not be anticipated or was unlikely.[35]

A further difference is between maximizing and satisficing consequentialism. According to maximizing consequentialism, only the best possible act is morally permitted. This means that acts with positive consequences are wrong if there are alternatives with even better consequences. One criticism of maximizing consequentialism is that it demands too much by requiring that people do significantly more than they are socially expected to. For example, if the best action for someone with a good salary would be to donate 70% of their income to charity, it would be morally wrong for them to only donate 65%. Satisficing consequentialism, by contrast, only requires that an act is "good enough" even if it is not the best possible alternative. According to this view, it is possible to do more than one is morally required to do.[36][b]

Mohism in ancient Chinese philosophy is one of the earliest forms of consequentialism. It arose in the 5th century BCE and argued that political action should promote justice as a means to increase the welfare of the people.[38]

Utilitarianism

The most well-known form of consequentialism is utilitarianism. In its classical form, it is an act consequentialism that sees happiness as the only source of intrinsic value. This means that an act is morally right if it produces "the greatest good for the greatest number" by increasing happiness and reducing suffering. Utilitarians do not deny that other things also have value, like health, friendship, and knowledge. However, they deny that these things have intrinsic value. Instead, they say that they have extrinsic value because they affect happiness and suffering. In this regard, they are desirable as a means but, unlike happiness, not as an end.[39] The view that pleasure is the only thing with intrinsic value is called ethical or evaluative hedonism.[40]

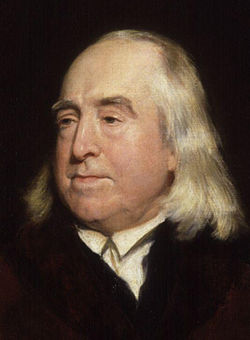

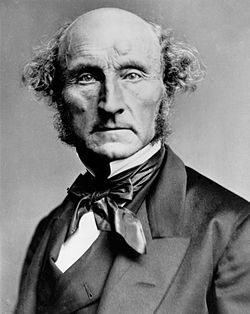

Classical utilitarianism was initially formulated by Jeremy Bentham at the end of the 18th century and further developed by John Stuart Mill. Bentham introduced the hedonic calculus to assess the value of consequences. Two key aspects of the hedonic calculus are the intensity and the duration of pleasure. According to this view, a pleasurable experience has a high value if it has a high intensity and lasts for a long time. A common criticism of Bentham's utilitarianism argued that its focus on the intensity of pleasure promotes an immoral lifestyle centered around indulgence in sensory gratification. Mill responded to this criticism by distinguishing between higher and lower pleasures. He stated that higher pleasures, like the intellectual satisfaction of reading a book, are more valuable than lower pleasures, like the sensory enjoyment of food and drink, even if their intensity and duration are the same.[42] Since its original formulation, many variations of utilitarianism have developed, including the difference between act and rule utilitarianism and between maximizing and satisficing utilitarianism.[43]

Deontology

Deontology assesses the moral rightness of actions based on a set of norms or principles. These norms describe the requirements that all actions need to follow.[44] They may include principles like telling the truth, keeping promises, and not intentionally harming others.[45] Unlike consequentialists, deontologists hold that the validity of general moral principles does not directly depend on their consequences. They state that these principles should be followed in every case since they express how actions are inherently right or wrong. According to moral philosopher David Ross, it is wrong to break a promise even if no harm comes from it.[46] Deontologists are interested in which actions are right and often allow that there is a gap between what is right and what is good.[47] Many focus on prohibitions and describe which acts are forbidden under any circumstances.[48]

Agent-centered and patient-centered

Agent-centered deontological theories focus on the person who acts and the duties they have. Agent-centered theories often focus on the motives and intentions behind people's actions, highlighting the importance of acting for the right reasons. They tend to be agent-relative, meaning that the reasons for which people should act depend on personal circumstances. For example, a parent has a special obligation to their child, while a stranger does not have this kind of obligation toward a child they do not know. Patient-centered theories, by contrast, focus on the people affected by actions and the rights they have. An example is the requirement to treat other people as ends and not merely as a means to an end.[49] This requirement can be used to argue, for example, that it is wrong to kill a person against their will even if this act would save the lives of several others. Patient-centered deontological theories are usually agent-neutral, meaning that they apply equally to everyone in a situation, regardless of their specific role or position.[50]

Kantianism

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) is one of the most well-known deontologists.[51] He states that reaching outcomes that people desire, such as being happy, is not the main purpose of moral actions. Instead, he argues that there are universal principles that apply to everyone independent of their desires. He uses the term categorical imperative for these principles, saying that they have their source in the structure of practical reason and are true for all rational agents. According to Kant, to act morally is to act in agreement with reason as expressed by these principles[52] while violating them is both immoral and irrational.[53]

Kant provided several formulations of the categorical imperative. One formulation says that a person should only follow maxims[c] that can be universalized. This means that the person would want everyone to follow the same maxim as a universal law applicable to everyone. Another formulation states that one should treat other people always as ends in themselves and never as mere means to an end. This formulation focuses on respecting and valuing other people for their own sake rather than using them in the pursuit of personal goals.[55]

In either case, Kant says that what matters is to have a good will. A person has a good will if they respect the moral law and form their intentions and motives in agreement with it. Kant states that actions motivated in such a way are unconditionally good, meaning that they are good even in cases where they result in undesirable consequences.[56]

Others

Divine command theory says that God is the source of morality. It states that moral laws are divine commands and that to act morally is to obey and follow God's will. While all divine command theorists agree that morality depends on God, there are disagreements about the precise content of the divine commands, and theorists belonging to different religions tend to propose different moral laws.[57] For example, Christian and Jewish divine command theorists may argue that the Ten Commandments express God's will[58] while Muslims may reserve this role for the teachings of the Quran.[59]

Contractualists reject the reference to God as the source of morality and argue instead that morality is based on an explicit or implicit social contract between humans. They state that actual or hypothetical consent to this contract is the source of moral norms and duties. To determine which duties people have, contractualists often rely on a thought experiment about what rational people under ideal circumstances would agree on. For example, if they would agree that people should not lie then there is a moral obligation to refrain from lying. Because it relies on consent, contractualism is often understood as a patient-centered form of deontology.[60][d] Famous social contract theorists include Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Rawls.[62]

Discourse ethics also focuses on social agreement on moral norms but says that this agreement is based on communicative rationality. It aims to arrive at moral norms for pluralistic modern societies that encompass a diversity of viewpoints. A universal moral norm is seen as valid if all rational discourse participants do or would approve. This way, morality is not imposed by a single moral authority but arises from the moral discourse within society. This discourse should aim to establish an ideal speech situation to ensure fairness and inclusivity. In particular, this means that discourse participants are free to voice their different opinions without coercion but are at the same time required to justify them using rational argumentation.[63]

Virtue ethics

The main concern of virtue ethics is how virtues are expressed in actions. As such, it is neither directly interested in the consequences of actions nor in universal moral duties.[64] Virtues are positive character traits like honesty, courage, kindness, and compassion. They are usually understood as dispositions to feel, decide, and act in a certain manner by being wholeheartedly committed to this manner. Virtues contrast with vices, which are their harmful counterparts.[65]

Virtue theorists usually say that the mere possession of virtues by itself is not sufficient. Instead, people should manifest virtues in their actions. An important factor is the practical wisdom, also called phronesis, of knowing when, how, and which virtue to express. For example, a lack of practical wisdom may lead courageous people to perform morally wrong actions by taking unnecessary risks that should better be avoided.[66]

Different types of virtue ethics differ on how they understand virtues and their role in practical life. Eudaimonism is the original form of virtue theory developed in Ancient Greek philosophy and draws a close relation between virtuous behavior and happiness. It states that people flourish by living a virtuous life. Eudaimonist theories often hold that virtues are positive potentials residing in human nature and that actualizing these potentials results in leading a good and happy life.[67] Agent-based theories, by contrast, see happiness only as a side effect and focus instead on the admirable traits and motivational characteristics expressed while acting. This is often combined with the idea that one can learn from exceptional individuals what those characteristics are.[67] Feminist ethics of care are another form of virtue ethics. They emphasize the importance of interpersonal relationships and say that benevolence by caring for the well-being of others is one of the key virtues.[68]

Influential schools of virtue ethics in ancient philosophy were Aristotelianism and Stoicism. According to Aristotle (384–322 BCE), each virtue[e] is a golden mean between two types of vices: excess and deficiency. For example, courage is a virtue that lies between the deficient state of cowardice and the excessive state of recklessness. Aristotle held that virtuous action leads to happiness and makes people flourish in life.[70] Stoicism emerged about 300 BCE[71] and taught that, through virtue alone, people can achieve happiness characterized by a peaceful state of mind free from emotional disturbances. The Stoics advocated rationality and self-mastery to achieve this state.[72] In the latter half of the 20th century, virtue ethics experienced a resurgence thanks to philosophers such as Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Martha Nussbaum.[73]

Other traditions

There are many other schools of normative ethics in addition to the three main traditions. Pragmatist ethics focuses on the role of practice and holds that one of the key tasks of ethics is to solve practical problems in concrete situations. It has certain similarities to utilitarianism and its focus on consequences but concentrates more on how morality is embedded in and relative to social and cultural contexts. Pragmatists tend to give more importance to habits than to conscious deliberation and understand morality as a habit that should be shaped in the right way.[74]

Postmodern ethics agrees with pragmatist ethics about the cultural relativity of morality. It rejects the idea that there are objective moral principles that apply universally to all cultures and traditions. It asserts that there is no one coherent ethical code since morality itself is irrational and humans are morally ambivalent beings.[75] Postmodern ethics instead focuses on how moral demands arise in specific situations as one encounters other people.[76]

Ethical egoism is the view that people should act in their self-interest or that an action is morally right if the person acts for their own benefit. It differs from psychological egoism, which states that people actually follow their self-interest without claiming that they should do so. Ethical egoists may act in agreement with commonly accepted moral expectations and benefit other people, for example, by keeping promises, helping friends, and cooperating with others. However, they do so only as a means to promote their self-interest. Ethical egoism is often criticized as an immoral and contradictory position.[77]

Normative ethics has a central place in most religions. Key aspects of Jewish ethics are to follow the 613 commandments of God according to the Mitzvah duty found in the Torah and to take responsibility for societal welfare.[78] Christian ethics puts less emphasis on following precise laws and teaches instead the practice of selfless love, such as the Great Commandment to "Love your neighbor as yourself".[79] The Five Pillars of Islam constitute a basic framework of Muslim ethics and focus on the practice of faith, prayer, charity, fasting during Ramadan, and pilgrimage to Mecca.[80]

Buddhists emphasize the importance of compassion and loving-kindness towards all sentient entities.[81] A similar outlook is found in Jainism, which has non-violence as its principal virtue.[82] Duty is a central aspect of Hindu ethics and is about fulfilling social obligations, which may vary depending on a person's social class and stage of life.[83] Confucianism places great emphasis on harmony in society and sees benevolence as a key virtue.[84] Taoism extends the importance of living in harmony to the whole world and teaches that people should practice effortless action by following the natural flow of the universe.[85] Indigenous belief systems, like Native American philosophy and the African Ubuntu philosophy, often emphasize the interconnectedness of all living beings and the environment while stressing the importance of living in harmony with nature.[86]

Remove ads

Metaethics

Summarize

Perspective

Metaethics is the branch of ethics that examines the nature, foundations, and scope of moral judgments, concepts, and values. It is not interested in which actions are right but in what it means for an action to be right and whether moral judgments are objective and can be true at all. It further examines the meaning of morality and other moral terms.[87] Metaethics is a metatheory that operates on a higher level of abstraction than normative ethics by investigating its underlying assumptions. Metaethical theories typically do not directly judge which normative ethical theories are correct. However, metaethical theories can still influence normative theories by examining their foundational principles.[88]

Metaethics overlaps with various branches of philosophy. On the level of ontology,[f] it examines whether there are objective moral facts.[90] Concerning semantics, it asks what the meaning of moral terms are and whether moral statements have a truth value.[91] The epistemological side of metaethics discusses whether and how people can acquire moral knowledge.[92] Metaethics overlaps with psychology because of its interest in how moral judgments motivate people to act. It also overlaps with anthropology since it aims to explain how cross-cultural differences affect moral assessments.[93]

Basic concepts

Metaethics examines basic ethical concepts and their relations. Ethics is primarily concerned with normative statements about what ought to be the case, in contrast to descriptive statements, which are about what is the case.[95][g] Duties and obligations express requirements of what people ought to do.[98] Duties are sometimes defined as counterparts of the rights that always accompany them. According to this view, someone has a duty to benefit another person if this other person has the right to receive that benefit.[99]

Obligation and permission are contrasting terms that can be defined through each other: to be obligated to do something means that one is not permitted not to do it and to be permitted to do something means that one is not obligated not to do it.[100][h] Some theorists define obligations in terms of values or what is good. When used in a general sense, good contrasts with bad. When describing people and their intentions, the term evil rather than bad is often employed.[101]

Obligations are used to assess the moral status of actions, motives, and character traits.[102] An action is morally right if it is in tune with a person's obligations and morally wrong if it violates them.[103] Supererogation is a special moral status that applies to cases in which the agent does more than is morally required of them.[104] To be morally responsible for an action usually means that the person possesses and exercises certain capacities or some form of control.[i] If a person is morally responsible then it is appropriate to respond to them in certain ways, for example, by praising or blaming them.[106]

Realism, relativism, and nihilism

A major debate in metaethics is about the ontological status of morality, questioning whether ethical values and principles are real. It examines whether moral properties exist as objective features independent of the human mind and culture rather than as subjective constructs or expressions of personal preferences and cultural norms.[107]

Moral realists accept the claim that there are objective moral facts. This view implies that moral values are mind-independent aspects of reality and that there is an absolute fact about whether a given action is right or wrong. A consequence of this view is that moral requirements have the same ontological status as non-moral facts: it is an objective fact whether there is an obligation to keep a promise just as it is an objective fact whether a thing is rectangular.[107] Moral realism is often associated with the claim that there are universal ethical principles that apply equally to everyone.[108] It implies that if two people disagree about a moral evaluation then at least one of them is wrong. This observation is sometimes taken as an argument against moral realism since moral disagreement is widespread in most fields.[109]

Moral relativists reject the idea that morality is an objective feature of reality. They argue instead that moral principles are human inventions. This means that a behavior is not objectively right or wrong but only subjectively right or wrong relative to a certain standpoint. Moral standpoints may differ between persons, cultures, and historical periods.[110] For example, moral statements like "Slavery is wrong" or "Suicide is permissible" may be true in one culture and false in another.[111][j] Some moral relativists say that moral systems are constructed to serve certain goals such as social coordination. According to this view, different societies and different social groups within a society construct different moral systems based on their diverging purposes.[113] Emotivism provides a different explanation, stating that morality arises from moral emotions, which are not the same for everyone.[114]

Moral nihilists deny the existence of moral facts. They reject the existence of both objective moral facts defended by moral realism and subjective moral facts defended by moral relativism. They believe that the basic assumptions underlying moral claims are misguided. Some moral nihilists conclude from this that anything is allowed. A slightly different view emphasizes that moral nihilism is not itself a moral position about what is allowed and prohibited but the rejection of any moral position.[115] Moral nihilism, like moral relativism, recognizes that people judge actions as right or wrong from different perspectives. However, it disagrees that this practice involves morality and sees it as just one type of human behavior.[116]

Naturalism and non-naturalism

A central disagreement among moral realists is between naturalism and non-naturalism. Naturalism states that moral properties are natural properties accessible to empirical observation. They are similar to the natural properties investigated by the natural sciences, like color and shape.[117] Some moral naturalists hold that moral properties are a unique and basic type of natural property.[k] Another view states that moral properties are real but not a fundamental part of reality and can be reduced to other natural properties, such as properties describing the causes of pleasure and pain.[119]

Non-naturalism argues that moral properties form part of reality and that moral features are not identical or reducible to natural properties. This view is usually motivated by the idea that moral properties are unique because they express what should be the case.[120] Proponents of this position often emphasize this uniqueness by claiming that it is a fallacy to define ethics in terms of natural entities or to infer prescriptive from descriptive statements.[121]

Cognitivism and non-cognitivism

The metaethical debate between cognitivism and non-cognitivism is about the meaning of moral statements and is a part of the study of semantics. According to cognitivism, moral statements like "Abortion is morally wrong" and "Going to war is never morally justified" are truth-apt, meaning that they all have a truth value: they are either true or false. Cognitivism claims that moral statements have a truth value but is not interested in which truth value they have. It is often seen as the default position since moral statements resemble other statements, like "Abortion is a medical procedure" or "Going to war is a political decision", which have a truth value.[122]

There is a close relation between the semantic theory of cognitivism and the ontological theory of moral realism. Moral realists assert that moral facts exist. This can be used to explain why moral statements are true or false: a statement is true if it is consistent with the facts and false otherwise. As a result, philosophers who accept one theory often accept the other as well. An exception is error theory, which combines cognitivism with moral nihilism by claiming that all moral statements are false because there are no moral facts.[123]

Non-cognitivism is the view that moral statements lack a truth value. According to this view, the statement "Murder is wrong" is neither true nor false. Some non-cognitivists claim that moral statements have no meaning at all. A different interpretation is that they have another type of meaning. Emotivism says that they articulate emotional attitudes. According to this view, the statement "Murder is wrong" expresses that the speaker has a negative moral attitude towards murder or disapproves of it. Prescriptivism, by contrast, understands moral statements as commands. According to this view, stating that "Murder is wrong" expresses a command like "Do not commit murder".[124]

Moral knowledge

The epistemology of ethics studies whether or how one can know moral truths. Foundationalist views state that some moral beliefs are basic and do not require further justification. Ethical intuitionism is one such view that says that humans have a special cognitive faculty through which they can know right from wrong. Intuitionists often argue that general moral truths, like "Lying is wrong", are self-evident and that it is possible to know them without relying on empirical experience. A different foundationalist position focuses on particular observations rather than general intuitions. It says that if people are confronted with a concrete moral situation, they can perceive whether right or wrong conduct was involved.[125]

In contrast to foundationalists, coherentists say that there are no basic moral beliefs. They argue that beliefs form a complex network and mutually support and justify one another. According to this view, a moral belief can only amount to knowledge if it coheres with the rest of the beliefs in the network.[125] Moral skeptics say that people are unable to distinguish between right and wrong behavior, thereby rejecting the idea that moral knowledge is possible. A common objection by critics of moral skepticism asserts that it leads to immoral behavior.[126]

Thought experiments are used as a method in ethics to decide between competing theories. They usually present an imagined situation involving an ethical dilemma and explore how people's intuitions of right and wrong change based on specific details in that situation.[127] For example, in Philippa Foot's trolley problem, a person can flip a switch to redirect a trolley from one track to another, thereby sacrificing the life of one person to save five. This scenario explores how the difference between doing and allowing harm affects moral obligations.[128] Another thought experiment, proposed by Judith Jarvis Thomson, examines the moral implications of abortion by imagining a situation in which a person gets connected without their consent to an ill violinist. In this scenario, the violinist dies if the connection is severed, similar to how a fetus dies in the case of abortion. The thought experiment explores whether it would be morally permissible to sever the connection within the next nine months.[129]

Moral motivation

On the level of psychology, metaethics is interested in how moral beliefs and experiences affect behavior. According to motivational internalists, there is a direct link between moral judgments and action. This means that every judgment about what is right motivates the person to act accordingly. For example, Socrates defends a strong form of motivational internalism by holding that a person can only perform an evil deed if they are unaware that it is evil. Weaker forms of motivational internalism say that people can act against their own moral judgments, for example, because of the weakness of the will. Motivational externalists accept that people can judge an act to be morally required without feeling a reason to engage in it. This means that moral judgments do not always provide motivational force.[130] A closely related question is whether moral judgments can provide motivation on their own or need to be accompanied by other mental states, such as a desire to act morally.[131]

Remove ads

Applied ethics

Summarize

Perspective

Applied ethics, also known as practical ethics,[132] is the branch of ethics and applied philosophy that examines concrete moral problems encountered in real-life situations. Unlike normative ethics, it is not concerned with discovering or justifying universal ethical principles. Instead, it studies how those principles can be applied to specific domains of practical life, what consequences they have in these fields, and whether additional domain-specific factors need to be considered.[133]

One of the main challenges of applied ethics is to breach the gap between abstract universal theories and their application to concrete situations.[134] For example, an in-depth understanding of Kantianism or utilitarianism is usually not sufficient to decide how to analyze the moral implications of a medical procedure like abortion. One reason is that it may not be clear how the Kantian requirement of respecting everyone's personhood applies to a fetus or, from a utilitarian perspective, what the long-term consequences are in terms of the greatest good for the greatest number.[135] This difficulty is particularly relevant to applied ethicists who employ a top-down methodology by starting from universal ethical principles and applying them to particular cases within a specific domain.[136] A different approach is to use a bottom-up methodology, known as casuistry. This method does not start from universal principles but from moral intuitions about particular cases. It seeks to arrive at moral principles relevant to a specific domain, which may not be applicable to other domains.[137] In either case, inquiry into applied ethics is often triggered by ethical dilemmas in which a person is subject to conflicting moral requirements.[138]

Applied ethics covers issues belonging to both the private sphere, like right conduct in the family and close relationships, and the public sphere, like moral problems posed by new technologies and duties toward future generations.[139] Major branches include bioethics, business ethics, and professional ethics. There are many other branches, and their domains of inquiry often overlap.[140]

Bioethics

Bioethics covers moral problems associated with living organisms and biological disciplines.[141] A key problem in bioethics is how features such as consciousness, being able to feel pleasure and pain, rationality, and personhood affect the moral status of entities. These differences concern, for example, how to treat non-living entities like rocks and non-sentient entities like plants in contrast to animals, and whether humans have a different moral status than other animals.[142] According to anthropocentrism, only humans have a basic moral status. This suggests that all other entities possess a derivative moral status only insofar as they impact human life. Sentientism, by contrast, extends an inherent moral status to all sentient beings. Further positions include biocentrism, which also covers non-sentient lifeforms, and ecocentrism, which states that all of nature has a basic moral status.[143]

Bioethics is relevant to various aspects of life and many professions. It covers a wide range of moral problems associated with topics like abortion, cloning, stem cell research, euthanasia, suicide, animal testing, intensive animal farming, nuclear waste, and air pollution.[144]

Bioethics can be divided into medical ethics, animal ethics, and environmental ethics based on whether the ethical problems relate to humans, other animals, or nature in general.[145] Medical ethics is the oldest branch of bioethics. The Hippocratic Oath is one of the earliest texts to engage in medical ethics by establishing ethical guidelines for medical practitioners like a prohibition to harm the patient.[146] Medical ethics often addresses issues related to the start and end of life. It examines the moral status of fetuses, for example, whether they are full-fledged persons and whether abortion is a form of murder.[147] Ethical issues also arise about whether a person has the right to end their life in cases of terminal illness or chronic suffering and if doctors may help them do so.[148] Other topics in medical ethics include medical confidentiality, informed consent, research on human beings, organ transplantation, and access to healthcare.[146]

Animal ethics examines how humans should treat other animals. This field often emphasizes the importance of animal welfare while arguing that humans should avoid or minimize the harm done to animals. There is wide agreement that it is wrong to torture animals for fun. The situation is more complicated in cases where harm is inflicted on animals as a side effect of the pursuit of human interests. This happens, for example, during factory farming, when using animals as food, and for research experiments on animals.[149] A key topic in animal ethics is the formulation of animal rights. Animal rights theorists assert that animals have a certain moral status and that humans should respect this status when interacting with them.[150] Examples of suggested animal rights include the right to life, the right to be free from unnecessary suffering, and the right to natural behavior in a suitable environment.[151]

Environmental ethics deals with moral problems relating to the natural environment including animals, plants, natural resources, and ecosystems. In its widest sense, it covers the whole cosmos.[152] In the domain of agriculture, this concerns the circumstances under which the vegetation of an area may be cleared to use it for farming and the implications of planting genetically modified crops.[153] On a wider scale, environmental ethics addresses the problem of global warming and people's responsibility on the individual and collective levels, including topics like climate justice and duties towards future generations. Environmental ethicists often promote sustainable practices and policies directed at protecting and conserving ecosystems and biodiversity.[154]

Business and professional ethics

Business ethics examines the moral implications of business conduct and how ethical principles apply to corporations and organizations.[155] A key topic is corporate social responsibility, which is the responsibility of corporations to act in a manner that benefits society at large. Corporate social responsibility is a complex issue since many stakeholders are directly and indirectly involved in corporate decisions, such as the CEO, the board of directors, and the shareholders. A closely related topic is the question of whether corporations themselves, and not just their stakeholders, have moral agency.[156] Business ethics further examines the role of honesty and fairness in business practices as well as the moral implications of bribery, conflict of interest, protection of investors and consumers, worker's rights, ethical leadership, and corporate philanthropy.[155]

Professional ethics is a closely related field that studies ethical principles applying to members of a specific profession, like engineers, medical doctors, lawyers, and teachers. It is a diverse field since different professions often have different responsibilities.[157] Principles applying to many professions include that the professional has the required expertise for the intended work and that they have personal integrity and are trustworthy. Further principles are to serve the interest of their target group, follow client confidentiality, and respect and uphold the client's rights, such as informed consent.[158] More precise requirements often vary between professions. A cornerstone of engineering ethics is to protect public safety, health, and well-being.[159] Legal ethics emphasizes the importance of respect for justice, personal integrity, and confidentiality.[160] Key factors in journalism ethics include accuracy, truthfulness, independence, and impartiality as well as proper attribution to avoid plagiarism.[161]

Other subfields

Many other fields of applied ethics are discussed in the academic literature. Communication ethics covers moral principles of communicative conduct. Two key issues in it are freedom of speech and speech responsibility. Freedom of speech concerns the ability to articulate one's opinions and ideas without the threats of punishment and censorship. Speech responsibility is about being accountable for the consequences of communicative action and inaction.[162] A closely related field is information ethics, which focuses on the moral implications of creating, controlling, disseminating, and using information.[163]

The ethics of technology examines the moral issues associated with the creation and use of any artifact, from simple spears to high-tech computers and nanotechnology.[164] Central topics in the ethics of technology include the risks associated with creating new technologies, their responsible use, and questions about human enhancement through technological means, such as performance-enhancing drugs and genetic enhancement.[165] Important subfields include computer ethics, ethics of artificial intelligence, machine ethics, ethics of nanotechnology, and nuclear ethics.[166]

The ethics of war investigates moral problems of war and violent conflicts. According to just war theory, waging war is morally justified if it fulfills certain conditions. These conditions are commonly divided into requirements concerning the cause to initiate violent activities, such as self-defense, and the way those violent activities are conducted, such as avoiding excessive harm to civilians in the pursuit of legitimate military targets.[167] Military ethics is a closely related field that is interested in the conduct of military personnel. It governs questions of the circumstances under which they are permitted to kill enemies, destroy infrastructure, and put the lives of their own troops at risk.[168] Additional topics are the recruitment, training, and discharge of military personnel.[169]

Other fields of applied ethics include political ethics, which examines the moral dimensions of political decisions,[170] educational ethics, which covers ethical issues related to proper teaching practices,[171] and sexual ethics, which addresses the moral implications of sexual behavior.[172]

Remove ads

Related fields

Summarize

Perspective

Value theory

Value theory, also called axiology,[l] is the philosophical study of value. It examines the nature and types of value.[174] A central distinction is between intrinsic and instrumental value. An entity has intrinsic value if it is good in itself or good for its own sake. An entity has instrumental value if it is valuable as a means to something else, for example, by causing something that has intrinsic value.[175] Other topics include what kinds of things have value and how valuable they are. For instance, axiological hedonists say that pleasure is the only source of intrinsic value and that the magnitude of value corresponds to the degree of pleasure. Axiological pluralists, by contrast, hold that there are different sources of intrinsic value, such as happiness, knowledge, and beauty.[176]

There are disagreements about the exact relation between value theory and ethics. Some philosophers characterize value theory as a subdiscipline of ethics while others see value theory as the broader term that encompasses other fields besides ethics, such as aesthetics and political philosophy.[177] A different characterization sees the two disciplines as overlapping but distinct fields.[178] The term axiological ethics is sometimes used for the discipline studying this overlap, that is, the part of ethics that studies values.[179] The two disciplines are sometimes distinguished based on their focus: ethics is about moral behavior or what is right while value theory is about value or what is good.[180] Some ethical theories, like consequentialism, stand very close to value theory by defining what is right in terms of what is good. But this is not true for ethics in general and deontological theories tend to reject the idea that what is good can be used to define what is right.[181][m]

Moral psychology

Moral psychology explores the psychological foundations and processes involved in moral behavior. It is an empirical science that studies how humans think and act in moral contexts. It is interested in how moral reasoning and judgments take place, how moral character forms, what sensitivity people have to moral evaluations, and how people attribute and react to moral responsibility.[183]

One of its key topics is moral development or the question of how morality develops on a psychological level from infancy to adulthood.[184] According to Lawrence Kohlberg, children go through different stages of moral development as they understand moral principles first as fixed rules governing reward and punishment, then as conventional social norms, and later as abstract principles of what is objectively right across societies.[185] A closely related question is whether and how people can be taught to act morally.[186]

Evolutionary ethics, a closely related field, explores how evolutionary processes have shaped ethics. One of its key ideas is that natural selection is responsible for moral behavior and moral sensitivity. It interprets morality as an adaptation to evolutionary pressure that augments fitness by offering a selective advantage.[187] Altruism, for example, can provide benefits to group survival by improving cooperation.[188] Some theorists, like Mark Rowlands, argue that morality is not limited to humans, meaning that some non-human animals act based on moral emotions. Others explore evolutionary precursors to morality in non-human animals.[189]

Descriptive ethics

Descriptive ethics, also called comparative ethics,[190] studies existing moral codes, practices, and beliefs. It investigates and compares moral phenomena in different societies and different groups within a society. It aims to provide a value-neutral and empirical description without judging or justifying which practices are objectively right. For instance, the question of how nurses think about the ethical implications of abortion belongs to descriptive ethics. Another example is descriptive business ethics, which describes ethical standards in the context of business, including common practices, official policies, and employee opinions. Descriptive ethics also has a historical dimension by exploring how moral practices and beliefs have changed over time.[191]

Descriptive ethics is a multidisciplinary field that is covered by disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, psychology, and history. Its empirical outlook contrasts with the philosophical inquiry into normative questions, such as which ethical principles are correct and how to justify them.[192]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The history of ethics studies how moral philosophy has developed and evolved in the course of history.[193] It has its origin in ancient civilizations. In ancient Egypt, the concept of Maat was used as an ethical principle to guide behavior and maintain order by emphasizing the importance of truth, balance, and harmony.[194][n] In ancient India starting in the 2nd millennium BCE,[196] the Vedas and later Upanishads were composed as the foundational texts of Hindu philosophy and discussed the role of duty and the consequences of one's actions.[197] Buddhist ethics originated in ancient India between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE and advocated compassion, non-violence, and the pursuit of enlightenment.[198] Ancient China in the 6th century BCE[o] saw the emergence of Confucianism, which focuses on moral conduct and self-cultivation by acting in agreement with virtues, and Daoism, which teaches that human behavior should be in harmony with the natural order of the universe.[200]

In ancient Greece, Socrates (c. 469–399 BCE)[201] emphasized the importance of inquiry into what a good life is by critically questioning established ideas and exploring concepts like virtue, justice, courage, and wisdom.[202] According to Plato (c. 428–347 BCE),[203] to lead a good life means that the different parts of the soul are in harmony with each other.[204] For Aristotle (384–322 BCE),[205] a good life is associated with being happy by cultivating virtues and flourishing.[206] Starting in the 4th century BCE, the close relation between right action and happiness was also explored by the Hellenistic schools of Epicureanism, which recommended a simple lifestyle without indulging in sensory pleasures, and Stoicism, which advocated living in tune with reason and virtue while practicing self-mastery and becoming immune to disturbing emotions.[207]

Ethical thought in the medieval period was strongly influenced by religious teachings. Christian philosophers interpreted moral principles as divine commands originating from God.[208] Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274 CE)[209] developed natural law ethics by claiming that ethical behavior consists in following the laws and order of nature, which he believed were created by God.[210] In the Islamic world, philosophers like Al-Farabi (c. 878–950 CE)[211] and Avicenna (980–1037 CE)[212] synthesized ancient Greek philosophy with the ethical teachings of Islam while emphasizing the harmony between reason and faith.[213] In medieval India, Hindu philosophers like Adi Shankara (c. 700–750 CE)[214] and Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE)[215][p] saw the practice of spirituality to attain liberation as the highest goal of human behavior.[217]

Moral philosophy in the modern period was characterized by a shift toward a secular approach to ethics. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679)[218] identified self-interest as the primary drive of humans. He concluded that it would lead to "a war of every man against every man" unless a social contract is established to avoid this outcome.[219] David Hume (1711–1776)[220] thought that only moral sentiments, like empathy, can motivate ethical actions while he saw reason not as a motivating factor but only as what anticipates the consequences of possible actions.[221] Immanuel Kant (1724–1804),[222] by contrast, saw reason as the source of morality. He formulated a deontological theory, according to which the ethical value of actions depends on their conformity with moral laws independent of their outcome. These laws take the form of categorical imperatives, which are universal requirements that apply to every situation.[223]

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831)[224] saw Kant's categorical imperative on its own as an empty formalism and emphasized the role of social institutions in providing concrete content to moral duties.[225] According to the Christian philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855),[226] the demands of ethical duties are sometimes suspended when doing God's will.[227] Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900)[228] formulated criticisms of both Christian and Kantian morality.[229] Another influential development in this period was the formulation of utilitarianism by Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832)[230] and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873).[231] According to the utilitarian doctrine, actions should promote happiness while reducing suffering and the right action is the one that produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people.[232]

An important development in 20th-century ethics in analytic philosophy was the emergence of metaethics.[234] Significant early contributions to this field were made by G. E. Moore (1873–1958),[235] who argued that moral values are essentially different from other properties found in the natural world.[236] R. M. Hare (1919–2002)[237] followed this idea in formulating his prescriptivism, which states that moral statements are commands that, unlike regular judgments, are neither true nor false.[238] J. L. Mackie (1917–1981)[239] suggested that every moral statement is false since there are no moral facts.[123] An influential argument for moral realism was made by Derek Parfit (1942–2017),[240] who argued that morality concerns objective features of reality that give people reasons to act in one way or another.[241] Bernard Williams (1929–2003)[242] agreed with the close relation between reasons and ethics but defended a subjective view instead that sees reasons as internal mental states that may or may not reflect external reality.[243]

Another development in this period was the revival of ancient virtue ethics by philosophers like Philippa Foot (1920–2010).[244] In the field of political philosophy, John Rawls (1921–2002)[245] relied on Kantian ethics to analyze social justice as a form of fairness.[246] In continental philosophy, phenomenologists such as Max Scheler (1874–1928)[247] and Nicolai Hartmann (1882–1950)[248] built ethical systems based on the claim that values have objective reality that can be investigated using the phenomenological method.[249] Existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980)[250] and Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986),[251] by contrast, held that values are created by humans and explored the consequences of this view in relation to individual freedom, responsibility, and authenticity.[252] This period also saw the emergence of feminist ethics, which questions traditional ethical assumptions associated with a male perspective and puts alternative concepts, like care, at the center.[253]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads