Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Eudaimonia

Human flourishing in ancient Greek philosophy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Eudaimonia (also spelled eudaemonia)(/juːdɪˈmoʊniə/; Ancient Greek: εὐδαιμονία [eu̯dai̯moníaː]) is a Greek word literally translating to the state or condition of good spirit, and which is commonly translated as happiness or welfare.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

In the works of Aristotle, eudaimonia was the term for the highest human good in older Greek tradition. It is the aim of practical philosophy-prudence, including ethics and political philosophy, to consider and experience what this state really is and how it can be achieved. It is thus a central concept in Aristotelian ethics and subsequent Hellenistic philosophy, along with the terms aretē (most often translated as virtue or excellence) and phronesis ('practical or ethical wisdom').[1]

Discussion of the links between ēthikē aretē (virtue of character) and eudaimonia (happiness) is one of the central concerns of ancient ethics, and a subject of disagreement. As a result, there are many varieties of eudaimonism.

Remove ads

Definition and etymology

Summarize

Perspective

In terms of its etymology, eudaimonia is an abstract noun derived from the words eû ("good, well") and daímōn ("spirit, deity").[2]

Semantically speaking, the word δαίμων (daímōn) derives from the same root of the Ancient Greek verb δαίομαι (daíomai, "to divide") allowing the concept of eudaimonia to be thought of as an "activity linked with dividing or dispensing, in a good way".

Definitions, a dictionary of Greek philosophical terms attributed to Plato himself but believed by modern scholars to have been written by his immediate followers in the Academy, provides the following definition of the word eudaimonia: "The good composed of all goods; an ability which suffices for living well; perfection in respect of virtue; resources sufficient for a living creature."

In his Nicomachean Ethics (§21; 1095a15–22), Aristotle says that everyone agrees that eudaimonia is the highest good for humans, but that there is substantial disagreement on what sort of life counts as doing and living well; i.e. eudaimon:

Verbally there is a very general agreement; for both the general run of men and people of superior refinement say that it is [eudaimonia], and identify living well and faring well with being happy; but with regard to what [eudaimonia] is they differ, and the many do not give the same account as the wise. For the former think it is some plain and obvious thing like pleasure, wealth or honour... [1095a17].[3]

Eudaimonia and areté

One important move in Greek philosophy to answer the question of how to achieve eudaimonia is to bring in another important concept in ancient philosophy, aretē ('virtue'). Aristotle says that the eudaimonic life is one of "virtuous activity in accordance with reason" [1097b22–1098a20]; even Epicurus, who argues that the eudaimonic life is the life of pleasure, maintains that the life of pleasure coincides with the life of virtue. So, the ancient ethical theorists tend to agree that virtue is closely bound up with happiness (areté is bound up with eudaimonia). However, they disagree on the way in which this is so. A major difference between Aristotle and the Stoics, for instance, is that the Stoics believed moral virtue was in and of itself sufficient for happiness (eudaimonia). For the Stoics, one does not need external goods, like physical beauty, in order to have virtue and therefore happiness.[4]

One problem with the English translation of areté as virtue is that we are inclined to understand virtue in a moral sense, which is not always what the ancients had in mind. For Aristotle, areté pertains to all sorts of qualities we would not regard as relevant to ethics, for example, physical beauty. So it is important to bear in mind that the sense of virtue operative in ancient ethics is not exclusively moral and includes more than states such as wisdom, courage, and compassion. The sense of virtue which areté connotes would include saying something like "speed is a virtue in a horse", or "height is a virtue in a basketball player". Doing anything well requires virtue, and each characteristic activity (such as carpentry, flute playing, etc.) has its own set of virtues. The alternative translation excellence (a desirable quality) might be helpful in conveying this general meaning of the term. The moral virtues are simply a subset of the general sense in which a human being is capable of functioning well or excellently.

Eudaimonia and happiness

Eudaimonia implies a positive and divine state of being that humanity is able to strive toward and possibly reach. A literal view of eudaimonia means achieving a state of being similar to a benevolent deity, or being protected and looked after by a benevolent deity. As this would be considered the most positive state to be in, the word is often translated as happiness although incorporating the divine nature of the word extends the meaning to also include the concepts of being fortunate, or blessed. Despite this etymology, however, discussions of eudaimonia in ancient Greek ethics are often conducted independently of any supernatural significance.

In his Nicomachean Ethics (1095a15–22) Aristotle says that eudaimonia means 'doing and living well'.[3] It is significant that synonyms for eudaimonia are living well and doing well. In the standard English translation, this would be to say that, "happiness is doing well and living well." The word happiness does not entirely capture the meaning of the Greek word. One important difference is that happiness often connotes being or tending to be in a certain pleasant state of mind. For example, when one says that someone is "a very happy person", one usually means that they seem subjectively contented with the way things are going in their life. They mean to imply that they feel good about the way things are going for them. In contrast, Aristotle suggests that eudaimonia is a more encompassing notion than feeling happy since events that do not contribute to one's experience of feeling happy may affect one's eudaimonia.

Eudaimonia depends on all the things that would make us happy if we knew of their existence, but quite independently of whether we do know about them. Ascribing eudaimonia to a person, then, may include ascribing such things as being virtuous, being loved and having good friends. But these are all objective judgments about someone's life: they concern whether a person is really being virtuous, really being loved, and really having fine friends. This implies that a person who has evil sons and daughters will not be judged to be eudaimonic even if he or she does not know that they are evil and feels pleased and contented with the way they have turned out (happy). Conversely, being loved by your children would not count towards your happiness if you did not know that they loved you (and perhaps thought that they did not), but it would count towards your eudaimonia. So, eudaimonia corresponds to the idea of having an objectively good or desirable life, to some extent independently of whether one knows that certain things exist or not. It includes conscious experiences of well-being, success, and failure, but also a whole lot more. (See Aristotle's discussion: Nicomachean Ethics, book 1.10–1.11.)

Because of this discrepancy between the meanings of eudaimonia and happiness, some alternative translations have been proposed. W.D. Ross suggests 'well-being' and John Cooper proposes flourishing. These translations may avoid some of the misleading associations carried by "happiness" although each tends to raise some problems of its own. In some modern texts therefore, the other alternative is to leave the term in an English form of the original Greek, as eudaimonia.

Remove ads

Classical views on eudaimonia and aretē

Summarize

Perspective

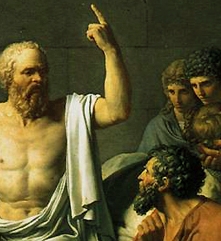

Socrates

What is known of Socrates' philosophy is almost entirely derived from Plato's writings. Scholars typically divide Plato's works into three periods: the early, middle, and late periods. They tend to agree also that Plato's earliest works quite faithfully represent the teachings of Socrates and that Plato's own views, which go beyond those of Socrates, appear for the first time in the middle works such as the Phaedo and the Republic.

As with all ancient ethical thinkers, Socrates thought that all human beings wanted eudaimonia more than anything else (see Plato, Apology 30b, Euthydemus 280d–282d, Meno 87d–89a). However, Socrates adopted a quite radical form of eudaimonism (see above): he seems to have thought that virtue is both necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia. Socrates is convinced that virtues such as self-control, courage, justice, piety, wisdom and related qualities of mind and soul are absolutely crucial if a person is to lead a good and happy (eudaimon) life. Virtues guarantee a happy life eudaimonia. For example, in the Meno, with respect to wisdom, he says: "everything the soul endeavours or endures under the guidance of wisdom ends in happiness" (Meno 88c).[5]

In the Apology, Socrates clearly presents his disagreement with those who think that the eudaimon life is the life of honour or pleasure, when he chastises the Athenians for caring more for riches and honour than the state of their souls.

Good Sir, you are an Athenian, a citizen of the greatest city with the greatest reputation for both wisdom and power; are you not ashamed of your eagerness to possess as much wealth, reputation, and honors as possible, while you do not care for nor give thought to wisdom or truth or the best possible state of your soul? (29e)[6] ... [I]t does not seem like human nature for me to have neglected all my own affairs and to have tolerated this neglect for so many years while I was always concerned with you, approaching each one of you like a father or an elder brother to persuade you to care for virtue. (31a–b; italics added)[7]

It emerges a bit further on that this concern for one's soul, that one's soul might be in the best possible state, amounts to acquiring moral virtue. So Socrates' pointing out that the Athenians should care for their souls means that they should care for their virtue, rather than pursuing honour or riches. Virtues are states of the soul. When a soul has been properly cared for and perfected, it possesses the virtues. Moreover, according to Socrates, this state of the soul, moral virtue, is the most important good. The health of the soul is incomparably more important for eudaimonia than (e.g.) wealth and political power. Someone with a virtuous soul is better off than someone who is wealthy and honoured but whose soul is corrupted by unjust actions. This view is confirmed in the Crito, where Socrates gets Crito to agree that the perfection of the soul, virtue, is the most important good:

And is life worth living for us with that part of us corrupted that unjust action harms and just action benefits? Or do we think that part of us, whatever it is, that is concerned with justice and injustice, is inferior to the body? Not at all. It is much more valuable...? Much more... (47e–48a)[7]

Here, Socrates argues that life is not worth living if the soul is ruined by wrongdoing.[8] In summary, Socrates seems to think that virtue is both necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia. A person who is not virtuous cannot be happy, and a person with virtue cannot fail to be happy. We shall see later on that Stoic ethics takes its cue from this Socratic insight.

Plato

Plato's great work of the middle period, the Republic, is devoted to answering a challenge made by the sophist Thrasymachus, that conventional morality, particularly the virtue of justice, actually prevents the strong man from achieving eudaimonia. Thrasymachus's views are restatements of a position which Plato discusses earlier on in his writings, in the Gorgias, through the mouthpiece of Callicles. The basic argument presented by Thrasymachus and Callicles is that justice (being just) hinders or prevents the achievement of eudaimonia because conventional morality requires that we control ourselves and hence live with un-satiated desires. This idea is vividly illustrated in book 2 of the Republic when Glaucon, taking up Thrasymachus' challenge, recounts a myth of the magical ring of Gyges. According to the myth, Gyges becomes king of Lydia when he stumbles upon a magical ring, which, when he turns it a particular way, makes him invisible, so that he can satisfy any desire he wishes without fear of punishment. When he discovers the power of the ring he kills the king, marries his wife and takes over the throne.[9] The thrust of Glaucon's challenge is that no one would be just if he could escape the retribution he would normally encounter for fulfilling his desires at whim. But if eudaimonia is to be achieved through the satisfaction of desire, whereas being just or acting justly requires suppression of desire, then it is not in the interests of the strong man to act according to the dictates of conventional morality. (This general line of argument reoccurs much later in the philosophy of Nietzsche.) Throughout the rest of the Republic, Plato aims to refute this claim by showing that the virtue of justice is necessary for eudaimonia.

The argument of the Republic is lengthy and complex. In brief, Plato argues that virtues are states of the soul, and that the just person is someone whose soul is ordered and harmonious, with all its parts functioning properly to the person's benefit. In contrast, Plato argues that the unjust man's soul, without the virtues, is chaotic and at war with itself, so that even if he were able to satisfy most of his desires, his lack of inner harmony and unity thwart any chance he has of achieving eudaimonia. Plato's ethical theory is eudaimonistic because it maintains that eudaimonia depends on virtue. On Plato's version of the relationship, virtue is depicted as the most crucial and the dominant constituent of eudaimonia.[10]

Aristotle

Aristotle's account is articulated in the Nicomachean Ethics and the Eudemian Ethics. In outline, for Aristotle, eudaimonia involves activity, exhibiting virtue (aretē sometimes translated as excellence) in accordance with reason. This conception of eudaimonia derives from Aristotle's essentialist understanding of human nature, the view that reason (logos sometimes translated as rationality) is unique to human beings and that the ideal function or work (ergon) of a human being is the fullest or most perfect exercise of reason. Basically, well-being (eudaimonia) is gained by proper development of one's highest and most human capabilities and human beings are "the rational animal". It follows that eudaimonia for a human being is the attainment of excellence (areté) in reason.

According to Aristotle, eudaimonia actually requires activity, action, so that it is not sufficient for a person to possess a squandered ability or disposition. Eudaimonia requires not only good character but rational activity. Aristotle clearly maintains that to live in accordance with reason means achieving excellence thereby. Moreover, he claims this excellence cannot be isolated and so competencies are also required appropriate to related functions. For example, if being a truly outstanding scientist requires impressive math skills, one might say "doing mathematics well is necessary to be a first rate scientist". From this it follows that eudaimonia, living well, consists in activities exercising the rational part of the psyche in accordance with the virtues or excellency of reason [1097b22–1098a20]. Which is to say, to be fully engaged in the intellectually stimulating and fulfilling work at which one achieves well-earned success. The rest of the Nicomachean Ethics is devoted to filling out the claim that the best life for a human being is the life of excellence in accordance with reason. Since the reason for Aristotle is not only theoretical but practical as well, he spends quite a bit of time discussing excellence of character, which enables a person to exercise his practical reason (i.e., reason relating to action) successfully.

Aristotle's ethical theory is eudaimonist because it maintains that eudaimonia depends on virtue. However, it is Aristotle's explicit view that virtue is necessary but not sufficient for eudaimonia. While emphasizing the importance of the rational aspect of the psyche, he does not ignore the importance of other goods such as friends, wealth, and power in a life that is eudaimonic. He doubts the likelihood of being eudaimonic if one lacks certain external goods such as good birth, good children, and beauty. So, a person who is hideously ugly or has "lost children or good friends through death" (1099b5–6), or who is isolated, is unlikely to be eudaimon. In this way, "dumb luck" (chance) can preempt one's attainment of eudaimonia.

Pyrrho

Pyrrho was the founder of Pyrrhonism. A summary of his approach to eudaimonia was preserved by Eusebius, quoting Aristocles of Messene, quoting Timon of Phlius, in what is known as the "Aristocles passage".

Whoever wants eudaimonia must consider these three questions: First, how are pragmata (ethical matters, affairs, topics) by nature? Secondly, what attitude should we adopt towards them? Thirdly, what will be the outcome for those who have this attitude?" Pyrrho's answer is that "As for pragmata they are all adiaphora (undifferentiated by a logical differentia), astathmēta (unstable, unbalanced, not measurable), and anepikrita (unjudged, unfixed, undecidable). Therefore, neither our sense-perceptions nor our doxai (views, theories, beliefs) tell us the truth or lie; so we certainly should not rely on them. Rather, we should be adoxastoi (without views), aklineis (uninclined toward this side or that), and akradantoi (unwavering in our refusal to choose), saying about every single one that it no more is than it is not or it both is and is not or it neither is nor is not.[11]

With respect to aretē, the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus said:

If one defines a system as an attachment to a number of dogmas that agree with one another and with appearances, and defines a dogma as an assent to something non-evident, we shall say that the Pyrrhonist does not have a system. But if one says that a system is a way of life that, in accordance with appearances, follows a certain rationale, where that rationale shows how it is possible to seem to live rightly ("rightly" being taken, not as referring only to aretē, but in a more ordinary sense) and tends to produce the disposition to suspend judgment, then we say that he does have a system.[12]

Epicurus

Epicurus' ethical theory is hedonistic. His views were very influential for the founders and best proponents of utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Hedonism is the view that pleasure is the only intrinsic good and that pain is the only intrinsic bad. An object, experience or state of affairs is intrinsically valuable if it is good simply because of what it is. Intrinsic value is to be contrasted with instrumental value. An object, experience or state of affairs is instrumentally valuable if it serves as a means to what is intrinsically valuable. To see this, consider the following example. Suppose a person spends their days and nights in an office, working at not entirely pleasant activities for the purpose of receiving money. Someone asks them "why do you want the money?", and they answer: "So, I can buy an apartment overlooking the ocean, and a red sports car." This answer expresses the point that money is instrumentally valuable because its value lies in what one obtains by means of it—in this case, the money is a means to getting an apartment and a sports car and the value of making this money dependent on the price of these commodities.

Epicurus identifies the good life with the life of pleasure. He understands eudaimonia as a more or less continuous experience of pleasure and, also, freedom from pain and distress. But Epicurus does not advocate that one pursue any and every pleasure. Rather, he recommends a policy whereby pleasures are maximized "in the long run". In other words, Epicurus claims that some pleasures are not worth having because they lead to greater pains, and some pains are worthwhile when they lead to greater pleasures. The best strategy for attaining a maximal amount of pleasure overall is not to seek instant gratification but to work out a sensible long term policy.[13]

Ancient Greek ethics is eudaimonist because it links virtue and eudaimonia, where eudaimonia refers to an individual's well-being. Epicurus' doctrine can be considered eudaimonist since Epicurus argues that a life of pleasure will coincide with a life of virtue.[14] He believes that we do and ought to seek virtue because virtue brings pleasure. Epicurus' basic doctrine is that a life of virtue is the life that generates the most pleasure, and it is for this reason that we ought to be virtuous. This thesis—the eudaimon life is the pleasurable life—is not a tautology as "eudaimonia is the good life" would be: rather, it is the substantive and controversial claim that a life of pleasure and absence of pain is what eudaimonia consists in.

One important difference between Epicurus' eudaimonism and that of Plato and Aristotle is that for the latter virtue is a constituent of eudaimonia, whereas Epicurus makes virtue a means to happiness. To this difference, consider Aristotle's theory. Aristotle maintains that eudaimonia is what everyone wants (and Epicurus would agree). He also thinks that eudaimonia is best achieved by a life of virtuous activity in accordance with reason. The virtuous person takes pleasure in doing the right thing as a result of a proper training of moral and intellectual character (See e.g., Nicomachean Ethics 1099a5). However, Aristotle does not think that virtuous activity is pursued for the sake of pleasure. Pleasure is a byproduct of virtuous action: it does not enter at all into the reasons why virtuous action is virtuous. Aristotle does not think that we literally aim for eudaimonia. Rather, eudaimonia is what we achieve (assuming that we are not particularly unfortunate in the possession of external goods) when we live according to the requirements of reason. Virtue is the largest constituent in a eudaimon life. By contrast, Epicurus holds that virtue is the means to achieve happiness. His theory is eudaimonist in that he holds that virtue is indispensable to happiness; but virtue is not a constituent of a eudaimon life, and being virtuous is not (external goods aside) identical with being eudaimon. Rather, according to Epicurus, virtue is only instrumentally related to happiness. So whereas Aristotle would not say that one ought to aim for virtue in order to attain pleasure, Epicurus would endorse this claim.

The Stoics

Stoic philosophy begins with Zeno of Citium c. 300 BC, and was developed by Cleanthes (331–232 BC) and Chrysippus (c. 280 – c. 206 BC) into a formidable systematic unity.[15] Zeno believed happiness was a "good flow of life"; Cleanthes suggested it was "living in agreement with nature", and Chrysippus believed it was "living in accordance with experience of what happens by nature."[15] Stoic ethics is a particularly strong version of eudaimonism. According to the Stoics, virtue is necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia. (This thesis is generally regarded as stemming from the Socrates of Plato's earlier dialogues.)

We saw earlier that the conventional Greek concept of arete is not quite the same as that denoted by virtue, which has Christian connotations of charity, patience, and uprightness, since arete includes many non-moral virtues such as physical strength and beauty. However, the Stoic concept of arete is much nearer to the Christian conception of virtue, which refers to the moral virtues. However, unlike Christian understandings of virtue, righteousness or piety, the Stoic conception does not place as great an emphasis on mercy, forgiveness, self-abasement (i.e. the ritual process of declaring complete powerlessness and humility before God), charity and self-sacrificial love, though these behaviors/mentalities are not necessarily spurned by the Stoics (they are spurned by some other philosophers of Antiquity). Rather Stoicism emphasizes states such as justice, honesty, moderation, simplicity, self-discipline, resolve, fortitude, and courage (states which Christianity also encourages).

The Stoics make a radical claim that the eudaimon life is the morally virtuous life. Moral virtue is good, and moral vice is bad, and everything else, such as health, honour and riches, are merely "neutral".[15] The Stoics therefore are committed to saying that external goods such as wealth and physical beauty are not really good at all. Moral virtue is both necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia. In this, they are akin to Cynic philosophers such as Antisthenes and Diogenes in denying the importance to eudaimonia of external goods and circumstances, such as were recognized by Aristotle, who thought that severe misfortune (such as the death of one's family and friends) could rob even the most virtuous person of eudaimonia. This Stoic doctrine re-emerges later in the history of ethical philosophy in the writings of Immanuel Kant, who argues that the possession of a "good will" is the only unconditional good. One difference is that whereas the Stoics regard external goods as neutral, as neither good nor bad, Kant's position seems to be that external goods are good, but only so far as they are a condition to achieving happiness.

Remove ads

Modern conceptions

Summarize

Perspective

"Modern Moral Philosophy"

Interest in the concept of eudaimonia and ancient ethical theory more generally had a revival in the 20th century. G. E. M. Anscombe in her article "Modern Moral Philosophy" (1958) argued that duty-based conceptions of morality are conceptually incoherent for they are based on the idea of a "law without a lawgiver".[16] She claims a system of morality conceived along the lines of the Ten Commandments depends on someone having made these rules.[17] Anscombe recommends a return to the eudaimonistic ethical theories of the ancients, particularly Aristotle, which ground morality in the interests and well-being of human moral agents, and can do so without appealing to any such lawgiver.

Julia Driver in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains:

Anscombe's article Modern Moral Philosophy stimulated the development of virtue ethics as an alternative to Utilitarianism, Kantian Ethics, and Social Contract theories. Her primary charge in the article is that, as secular approaches to moral theory, they are without foundation. They use concepts such as "morally ought", "morally obligated", "morally right", and so forth that are legalistic and require a legislator as the source of moral authority. In the past God occupied that role, but systems that dispense with God as part of the theory are lacking the proper foundation for meaningful employment of those concepts.[18]

Modern psychology

Models of eudaimonia in psychology and positive psychology emerged from early work on self-actualization and the means of its accomplishment by researchers such as Erik Erikson, Gordon Allport, and Abraham Maslow (hierarchy of needs).[19]

Theories include Diener's tripartite model of subjective well-being, Ryff's Six-factor Model of Psychological Well-being, Keyes work on flourishing, and Seligman's contributions to positive psychology and his theories on authentic happiness and P.E.R.M.A. Related concepts are happiness, flourishing, quality of life, contentment,[20] and meaningful life.

The Japanese concept of ikigai has been described as eudaimonic well-being, as it "entails actions of devoting oneself to pursuits one enjoys and is associated with feelings of accomplishment and fulfillment."[21]

Positive psychology on eudaimonia

The "Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being" developed in Positive Psychology lists six dimensions of eudaimonia:[22]

- self-discovery;

- perceived development of one's best potentials;

- a sense of purpose and meaning in life;

- investment of significant effort in pursuit of excellence;

- intense involvement in activities; and

- enjoyment of activities as personally expressive.

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads