Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Gotse Delchev

Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (1872–1903) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

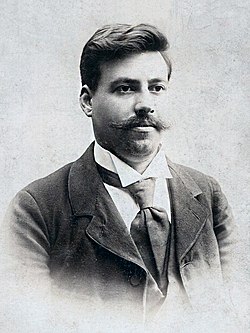

Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Bulgarian: Георги Николов Делчев; Macedonian: Ѓорѓи Николов Делчев; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903), known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev (Гоце Делчев),[note 1] was a prominent Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji) and one of the most important leaders of what is commonly known as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).[1] He was active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions, as well as in Bulgaria, at the turn of the 20th century.[2][3] Delchev was IMRO's foreign representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria.[4] As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC) for a period,[5] participating in the work of its governing body.[6] He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising.

Born into a Bulgarian Millet affiliated family in Kukush (today Kilkis in Greece),[7][8][9] then in the Salonika vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, in his youth he was inspired by the ideals of earlier Bulgarian revolutionaries such as Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev, who envisioned the creation of a Bulgarian republic of ethnic and religious equality, as part of an imagined Balkan Federation.[10] Delchev completed his secondary education in the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki and entered the Military School of His Princely Highness in Sofia, but at the final stage of his study, he was dismissed for holding socialist literature.[11][12][13] Then he returned to Ottoman Macedonia and worked as a Bulgarian Exarchate schoolteacher, and immediately became an activist of the newly-found revolutionary movement in 1894.[14]

Although considering himself to be an inheritor of the Bulgarian revolutionary traditions,[6] he opted for Macedonian autonomy.[15] For him, like for many Slavic Macedonian prominent intellectuals, originating from an area with mixed population,[16] the idea of being 'Macedonian' acquired the importance of a certain native loyalty, that constructed a specific spirit of "local patriotism" and "multi-ethnic regionalism".[17] He maintained the slogan promoted by William Ewart Gladstone, "Macedonia for the Macedonians", including all different nationalities inhabiting the area.[18][19][20] Delchev was also an adherent of incipient socialism.[21][16][22] His political agenda became the establishment through revolution of autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople regions into the framework of the Ottoman Empire, which in the case of Macedonia would lead to her full independence and inclusion within a future Balkan Federation.[23][7][24][11] Despite having been educated in the spirit of Bulgarian nationalism, he was an opponent of the incorporation of Macedonia inside Bulgaria.[25][26][27][15] Furthermore, he revised the Organization's first statute, where the membership was allowed only for Bulgarians, in order for it to depart from the exclusively Bulgarian nature, and IMRO begun to acquire a more separatist stance.[28][29][24][30] In this way he emphasized the importance of cooperation among all ethnic groups in the territories concerned in order to obtain full political autonomy.[31][14]

Delchev is considered a national hero in Bulgaria and North Macedonia. In the latter it is claimed he was an ethnic Macedonian revolutionary. Thus, his legacy has been disputed between both countries.[32][33] Delchev's autonomist ideas have stimulated the subsequent development of Macedonian nationalism.[34][11] Nevertheless, for part of the members of IMRO behind the idea of autonomy a reserve plan for eventual annexation by Bulgaria was hidden.[35][36] Per some of his contemporaries, closely associated with him, Delchev supported Macedonia's incorporation into Bulgaria as another option too.[16] Other researchers find the identity of Delchev and other IMRO figures to be open to different interpretations.

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

He was born to a large Bulgarian family on 4 February 1872 (23 January according to the Julian calendar) in Kılkış (Kukush), then in the Ottoman Empire (today in Greece), to Nikola and Sultana. He was christened as Georgi.[37] During the 1860s and 1870s, Kukush was under the jurisdiction of the Bulgarian Uniate Church,[38][39] but after 1884 most of its population gradually joined the Bulgarian Exarchate.[40] As a student, Delchev studied first at the Bulgarian Uniate primary school and then at the Bulgarian Exarchate junior high school.[41] He also read widely in the town's chitalishte (community cultural center), where he was impressed with revolutionary books, and was especially imbued with thoughts of the liberation of Bulgaria.[42] In 1888 his family sent him to the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki, where he organized and led a secret revolutionary brotherhood.[43] Delchev also distributed revolutionary literature, which he acquired from the school's graduates who studied in Bulgaria. Bulgarian students graduating from high school were faced with few career prospects and Delchev decided to follow the path of his former schoolmate Boris Sarafov, entering the military school in Sofia in 1891. He became disappointed with life in Bulgaria, especially the commercialized life of the society in Sofia and with the authoritarian politics of the prime minister Stefan Stambolov,[43] accused of being a dictator.[6]

Delchev spent his leaves from school in the company of socialists and Macedonian-born emigrants, most of them belonged to the Young Macedonian Literary Society.[43] One of his friends was Vasil Glavinov, a future leader of the Macedonian-Adrianople Social Democratic Group, a faction of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers Party.[37] Through Glavinov and his comrades, he came into contact with different people, who offered a new form of social struggle. In June 1892, Delchev and the journalist Kosta Shahov, a chairman of the Young Macedonian Literary Society, met in Sofia with Ivan Hadzhinikolov, a bookseller from Thessaloniki (Salonika). Hadzhinikolov disclosed at this meeting his plans to create a revolutionary organization in Ottoman Macedonia. They discussed together its basic principles and agreed fully on all scores. Delchev explained that he had no intention of remaining an officer and promised after graduating from the Military School, he would return to Macedonia to join the organization.[44] In September 1894, only a month before graduation, he was expelled for his socialist and revolutionary ideas.[45][46][26] He was given the possibility to enter the Army again by re-applying for a commission, but he refused. Afterwards he returned to Macedonia to become a teacher and set up secret committees, based on Vasil Levski's example.[46] At that time, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) was in its early stages of development, forming its committees around the Bulgarian Exarchate schools in order to exploit the extensive school system.[47][48]

Teacher and revolutionary

In Ottoman Salonika, IMRO was founded in 1893, by a small band of anti-Ottoman Macedono-Bulgarian revolutionaries, including Hadzhinikolov. The earliest known statute of the Organization calls it Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC).[12][51] It was decided at a meeting in Resen in August 1894 to preferably recruit teachers from the Bulgarian schools as committee members.[45] Although Delchev despised the Exarchate policy in Macedonia, in 1894 he became a teacher in an Exarchate school in Štip.[52][53] There he met another teacher, Dame Gruev, who was also among the founders of IMRO and a leader of the newly established local committee.[37] Gruev told him about the existence of the Organization.[46] Delchev impressed Gruev with his honesty and joined the Organization immediately, gradually becoming one of its main leaders.[26] Delchev advocated for the establishment of a secret revolutionary network, that would prepare the population for an armed uprising against the Ottoman rule, based on Levski's example.[14] They shared common views with Gruev that the liberation had to be achieved internally by a Macedonian organization without any foreign intervention.[26][45] Therefore, Gruev concentrated his attention on Štip, while Delchev attempted to win over the surrounding villages.[45] It is unknown how many active members the Organization had from 1893 to 1897. Despite his and Gruev's efforts, the number of members grew slowly.[26] In a letter from 1895, Delchev explained that the liberation of Macedonia as a state lies in an internal uprising for which a systematic agitation was conducted in order for the population to be ready in the near future, otherwise the result of a premature uprising would be tragic.[37] Delchev travelled during the vacations throughout Macedonia and established and organized committees in villages and cities. In this period, he adopted Ahil (Archilles) as his nom de guerre.[37] Furthermore, he organized secret border crossing points towards Bulgaria near Kyustendil for easier infiltration of revolutionary propaganda literature.[26]

Delchev also established contacts with some of the leaders of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC). Its official declaration was a struggle for the autonomy of the Macedonian and Adrianople regions.[54][55] However, as a rule, most of SMAC's leaders were officers with strong connections with the Bulgarian governments and prince Ferdinand, waging terrorist struggle against the Ottomans in the hope of provoking a war and thus Bulgarian annexation of both areas. In late 1895 he arrived in Bulgaria's capital Sofia from the name of the "Bulgarian Central Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committee" to prevent any foreign interference in its work.[56] In February 1896, he met SMAC's new leader Danail Nikolaev, their conversation was turbulent and short. Namely, Nikolaev asserted that the only way to freedom was with trained Bulgarian soldiers and clandestine aid and finance of the Bulgarian government. Moreover, he considered Delchev a brash youngster and deemed unreal and absurd the idea of peasant uprising by revolutionary impulsion of the Macedonian Slavs.[26][52] SMAC wanted IMRO to be subordinated to them, and Bulgarian army officers to dominate their activity, while IMRO wanted to remain independent of Bulgarian governmental control.[35] After spending the 1895/1896 school year as a teacher in the town of Bansko, in May 1896 he was arrested by the Ottoman authorities as a person suspected of revolutionary activity and spent about a month in jail. Delchev participated in the Thessaloniki Congress of the IMRO in 1896.[26] The Central Committee was placed in Salonika. He, along with Gyorche Petrov, wrote the new organization's statute, which divided Macedonia and Adrianople areas into seven regions, each with a regional structure and secret police, following the Internal Revolutionary Organization's example.[12][57] Afterwards, Delchev gave his resignation as a teacher and in the same year, he moved back to Bulgaria.[58]

Revolutionary activity as part of the leadership of the Organization

The Central Committee regarded as necessary to have trustworthy permanent representatives in Sofia in order to mediate the tense relations with the SMAC, because IMRO looked to avoid a break since it was largely dependent on Bulgarian state material and financial assistance. Thus, from November 1896, Delchev was put in charge of the Foreign Representation of the IMRO alongside Petrov who joined him in March 1897. Besides the dialogue with the SMAC, they were assigned to acquire funds or additional support and preserve ties with all those in the Bulgaria who were approving of the Macedonian cause.[37][19][26] Delchev envisioned independent production of weapons and traveled in 1897 to Odessa,[37] where he met with Armenian revolutionaries Stepan Zorian and Christapor Mikaelian to exchange terrorist skills and especially bomb-making.[59] That resulted in the establishment of a bomb manufacturing plant in the village of Sabler near Kyustendil in Bulgaria. The bombs were later smuggled across the Ottoman border into Macedonia.[58] In the period from 1897 to 1898 the Organization decided to create permanent acting armed komitadji bands (chetas) in every district, with Delchev as their leader.[60] He was the first to organize and lead a band into Macedonia with the purpose of robbing or kidnapping rich Turks. This activity of his had variable success.[52] His experiences demonstrate the weaknesses and difficulties which the Organization faced in its early years.[61]

After 1897 there was a rapid growth of secret Bulgarian army officers' brotherhoods, whose members by 1900 numbered about a thousand.[62] Much of the brotherhoods' activists were involved in the revolutionary activity of the IMRO, collecting funds and petitions in support of the Macedonian cause.[63] They were formed on the initiative of Petrov by officers with whom he managed to develop good raport, one of them being the lieutenant Boris Sarafov.[26] Delchev was also among the main supporters of their activities.[64] Relations with the SMAC did not improve and remained tense until 1899. In May that year, on the 6th Congress of the SMAC, Sarafov was elected as new president after being proposed by Petrov and Delchev.[45] However, their first choice was Dimitar Blagoev by whose socialist ideas Delchev was specifically influenced, but he declined. Thus, they settled for Delchev's former schoolmate Sarafov, who they saw as favorable to IMRO's ideas even though their personalities differed.[26][11] IMRO delegates Delchev and Petrov became by rights members of the leadership of the SMAC in May 1899, thus this signaled the start of a period of close cooperation.[65][26] Although Sarafov proved capable of propagating the Macedonian cause and raise money, he was also arrogant and unpredictable, so Delchev and Petrov were unable to utilize him.[11]

In 1900, Delchev resided for a while in Burgas, where he organized another bomb manufacturing plant, whose dynamite was used later by the Boatmen of Thessaloniki.[66] In March 1900, Gotse Delchev, accompanied by Lazar Madzharov, went on a tour of Strandzha Mountain, aiming better coordination between Macedonian and Thracian revolutionary committees, returning to Burgas in mid-April.[67] After the SMAC's assassination of the Romanian newspaper editor Ștefan Mihăileanu in July, who had published unflattering remarks about the Macedonian affairs, Bulgaria and Romania were brought to the brink of war. At that time Delchev was preparing to organize a detachment which, in a possible war to support the Bulgarian army by its actions in Northern Dobruja, where a compact Bulgarian population was available.[68] Meanwhile, Sarafov was reelected as president in August, and with that the involvement of Delchev and Petrov in the SMAC's work resumed. However, deep disagreements still existed, essentially concerning the ultimate aim of the autonomy which in IMRO's case was independent Macedonia as part of a future Balkan Federation, while for the SMAC it was unification with Bulgaria. Other instances were difference in mentality and social origin between "schoolteachers" and "officers", of which the latter desired to command the liberation operations, as well as the distrust by them in the idea of a peasant uprising led by teachers. The chief figure in this contemptuous attitude was General Ivan Tsonchev, who was intimate with the Bulgarian prince Ferdinand and his court.[26] He was also the leader of those who intended through the cooperation to subordinate IMRO and he begun to work against Delchev and Petrov.[12] Tsonchev and his supporters insisted on an immediate uprising which will be led by Bulgarian army officers. Consequently, Delchev with Petrov resisted Tsonchev's faction, as they asserted that the time for a uprising is not ripe since the population is still not ready to liberate itself, thus political agitation and guerilla fighting should proceed. On the other hand, Tsonchev's faction briefly contemplated assassinating them. Towards the end of 1900, the relations between the IMRO and SMAC deteriorated gradually.[45][26] Furthermore, the ideologically inclined Ivan Garvanov offered Tsonchev control over IMRO, after managing to become de facto its leader by acquiring the archive and accounts, following the arrest of the Central Committee members in the beginning of 1901.[52] Therefore, in March 1901, Delchev alongside Petrov sent a circular to local IMRO committee leaders, denouncing the attempt of SMAC to seize the direction of IMRO. They ordered the termination of all relations with it, as well as ordered all local committees to refuse any transition of any armed group which did not have a pass signed by him or Petrov, and their weapons to be seized.[26] Delchev intended to promote an election list directed against Tsonchev at SMAC's 9th Congress in July 1901.[45] Nevertheless, Sarafov was replaced by Stoyan Mihaylovski, while Tsonchev became the vice-president and assumed full control with his officers. After this, the relations between the SMAC and IMRO were limited and increasingly hostile.[26] In September, Delchev and Petrov were replaced as foreign representatives of IMRO. From 1901 to 1902, Delchev made an important inspection in Macedonia, touring all revolutionary districts there. He also led the congress of the Adrianople revolutionary district held in Plovdiv in April 1902. Afterwards he inspected IMRO's structures in the Central Rhodopes. The inclusion of the rural areas into the organizational districts contributed to the expansion of the Organization and the increase in its membership, while providing the essential prerequisites for the formation of its military power, at the same time having Delchev as its military advisor (inspector) and chief of all internal revolutionary bands.[58] In August, despite being invited he refused to attend the 10th Congress of the SMAC, which escalated the crisis with IMRO.[26]

In late December 1902, Garvanov unexpectedly declared that a congress of IMRO will take place the following month. Particularly intended for a date of a general uprising in 1903 to be decided.[26] By that time two strong tendencies had crystallized within IMRO. The Bulgarian nationalist majority was convinced that if the Organization would unleash a general uprising, it will lead to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.[22] On the other hand, the leaders of the IMRO leftists, Delchev with Petrov strongly protested, elaborating that the komitadjis are not adequately prepared and a premature uprising will only result in massacre, endangering the whole organization as well.[60][22] However, without waiting for their reaction, Garvanov organized the Salonika Congress on 15 January 1903, with only 17 delegates cautiously selected to be favorable to his ideas.[52][26] Delchev did not participate nor any of the other leaders or founders of IMRO.[69] A general uprising was debated and under the influence of Garvanov it was decided to stage one in May 1903. The opponents of the decision refused to recognize it.[26] Delchev, with the anarchist Mihail Gerdzhikov, proposed instead intensifying terrorist tactics and guerilla tactics, which came to approval and postponement of the uprising by Garvanov's supporters, on the condition that it will lead to provoking revolts in the districts estimated sufficiently prepared.[70][71] Thus Delchev and Petrov established terror units, which were associated with the anarchist organization Macedonian Secret Revolutionary Committee.[22][26][12] With the arrival of spring, IMRO multiplied the attacks, and the violence grew significantly. Delchev went to Macedonia to meet in the Serres region with Yane Sandanski seeking support and understanding, as he was always ideologically concurred to him, and he shared the view to oppose the general uprising decision.[52][37] Towards the end of March 1903, Delchev with his band destroyed the 30 meters long Salonika-Istanbul railway bridge over the Angista river between Serres and Drama, aiming to test the new terror tactics.[37][26]

Death and aftermath

In late April he set out for Thessaloniki to meet with Dame Gruev after his release from prison in March 1903. Delchev hoped that he will argue against the uprising, but Gruev wanted it to proceed since the course of events had become unrepairable. Therefore, Delchev agreed to prepare as much he can in the Serres district and headed that way with the intention of holding a regional congress in Serres to lay out his plans for the uprising.[52] At the same time, the terror initiated by IMRO culminated on 28 April when the Boatmen of Thessaloniki started their terrorist attacks in the city, of whom only Delchev knew they will happen.[26] As a consequence martial law was declared in the city and many Ottoman soldiers and "bashibozouks" were concentrated in the Salonika vilayet. This increased tension led eventually to the tracking of Delchev's cheta and his subsequent death.[12][76] With his cheta he arrived in the village of Banitsa on 2 May for a meeting with Dimo Hadzhidimov. Soon after, they were surrounded and a skirmish followed in which Delchev was killed on 4 May 1903, with a shot to the chest,[26] by Ottoman troops led by his former schoolmate Hussein Tefikov.[60][77] A consular source reported that the skirmish occurred after betrayal by local villager.[78] The Ottomans sent his severed head to Salonika.[52] Thus the Macedonian liberation movement lost its most important organizer and ideologist, on the eve of the Ilinden Uprising.[14] He was recognized as "the most capable and most honest Komitadji" by missionaries.[2] After being identified by the local authorities in Serres, the bodies of Delchev and his comrade, Dimitar Gushtanov, were buried in a common grave in Banitsa. Following the skirmish, more than 500 arrests were made in various districts of Serres and 1,700 households petitioned to return from Exarchist to Patriarchist jurisdiction.[35] Soon afterwards IMRO, aided by SMAC, organized the uprising against the Ottoman Empire, which after initial successes, was defeated with many casualties.[79] Two of his brothers, Mitso and Milan were also killed fighting against the Ottomans as militants in the IMRO chetas of the Bulgarian voivodas Hristo Chernopeev and Krastyo Asenov in 1901 and 1903, respectively. The Bulgarian government later granted a pension to their father Nikola, because of the contribution of his sons to the freedom of Macedonia.[80] During the Second Balkan War of 1913, Kilkis, which had been annexed by Bulgaria in the First Balkan War, was taken by the Greeks. Virtually all of its pre-war 7,000 Bulgarian inhabitants, including Delchev's family, were expelled to Bulgaria by the Greek Army.[81] During Balkan Wars, when Bulgaria was temporarily in control of the area, Delchev's remains were transferred to Xanthi, then in Bulgaria. After Western Thrace was ceded to Greece in 1919, the relic was brought to Plovdiv and in 1923 to Sofia, where it rested until after World War II.[82] During World War II, the area was taken by the Kingdom of Bulgaria again and Delchev's grave near Banitsa was restored.[83] In May 1943, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of his death, a memorial plaque was set in Banitsa, in the presence of his sisters and other public figures.[84]

The first biographical book about Delchev was issued in 1904 by his friend and comrade in arms, the Bulgarian poet Peyo Yavorov.[85] The most detailed biography of Delchev in English was written by English historian Mercia MacDermott called Freedom or Death: The Life of Gotse Delchev, published in 1978 and translated into Bulgarian in 1979.[86][87]

Remove ads

Views

Summarize

Perspective

The international, cosmopolitan views of Delchev could be summarized in his proverbial sentence: "I understand the world solely as a field for cultural competition among the peoples".[88][89] Per MacDermott, his saying presupposes a world without political and economic conflicts and one which has a very high degree of mutual friendship and co-operation on an international level.[46] In the late 19th century the anarchists and socialists from Bulgaria linked their struggle closely with the revolutionary movements in Macedonia and Thrace.[90] Thus, as a young cadet in Sofia Delchev became a member of a left-wing circle, where he was influenced by modern Marxist and Bakunin's ideas.[91] His views were formed also under the influence of the ideas of earlier anti-Ottoman fighters as Levski, Botev, and Stoyanov,[15] who were among the founders of the Bulgarian Internal Revolutionary Organization, the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee and the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee, respectively. Later he participated in the Internal Organization's struggle as a well-educated leader.

According to MacDermott, based on the Bulgarian historian Konstatin Pandev, he was the co-author of BMARC's statute, although this is disputed.[92][93][26] Delchev initiated the changing of the exclusively Bulgarian character of the organization, which determined that members of the organization could be only Bulgarians. Accordingly, a new supra-nationalistic statute was created by him and Petrov in 1896 or 1902, with whom under a new name the Secret Macedono-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (SMARO), was to become an insurgent organization, open to all Macedonians and Thracians regardless of nationality, who wished to participate in the movement for their autonomy.[26][24] This aim was especially facilitated by the unrealized 23rd. article of the Treaty of Berlin (1878), which promised future autonomy for unspecified territories in European Turkey, settled with Christian population.[94] Delchev's main goal, along with the other revolutionaries, was the implementation of Article 23 of the treaty, aimed at acquiring full autonomy of Macedonia and the Adrianople.[95] Delchev is considered to be the leader of the leftist faction within IMRO, which firmly opposed the inclusion of Macedonia into Bulgaria, and sought the autonomy to evolve in independence for Macedonia, with her subsequent incorporation into a envisioned Balkan Federation.[96][22] Despite his Bulgarian loyalty, he was against any chauvinistic propaganda and nationalist disputes over Macedonia and the Adrianople.[24][97] On the other hand, per Bulgarian academic sources and some of his contemporaries, Delchev supported Macedonia's eventual incorporation into Bulgaria.[98][99][100][101] Per Anastasia Karakasidou, Delchev and others with same ideas like him often left the links between an independent Macedonia and neighboring Bulgaria ill-defined.[20] For militants such as Delchev and other leftists that participated in the national movement retaining a political outlook, national liberation meant "radical political liberation through shaking off the social shackles".[102] According to researcher James Horncastle, he believed that revolutionary terror was necessary to create an autonomous Macedonia.[103] Per Delchev, no outside force could or would help the Organization and it ought to rely only upon itself and only upon its own will and strength. He thought that any intervention by Bulgaria would provoke intervention by the neighboring states as well and could result in Macedonia and Thrace being torn apart. That is why the peoples of these two regions had to win their own freedom and independence, within the frontiers of an autonomous Macedonian-Adrianople state.[104]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Communist period

During World War II, the Macedonian communist partisans associated their struggle with the ideals of Delchev and IMRO. The culmination of the struggle was the establishment of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia in 1944.[106][107] In late 1944, new communist regimes came into power in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia and their policy on the Macedonian Question was committed to the supporting of a distinct Macedonian nationality.[107][108] The region of Macedonia was proclaimed as the connecting link for the establishment of a future Balkan Communist Federation.

The newly formed Socialist Republic of Macedonia was integrated into the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and was characterized as the natural result of Delchev's aspirations for autonomous Macedonia.[109] Initially some of the Macedonian communist leaders, such as Lazar Koliševski, questioned the extent of Delchev's alleged Macedonian national consciousness.[11][110][111] In 1946, communist activist Vasil Ivanovski acknowledged that Delchev did not have a clear view of a "Macedonian national character", but stated that his struggle made the free and autonomous Macedonia a possibility.[11] On 7 October 1946, with the approval of the Bulgarian government, by the initiative of Todor Pavlov,[112] as a gesture of goodwill and as part of the policy to foster the development of Macedonian national consciousness, Delchev's remains were transported from Sofia to Skopje.[113][114] On 10 October, the bones were enshrined in a marble sarcophagus in the yard of the church "Sveti Spas", where they have stayed since.[113]

After realizing that the Balkan collective memory had already marked the heroes of the Macedonian revolutionary movement as Bulgarians, Macedonian communist authorities considered this unjustified and exerted efforts to reclaim Delchev for the Macedonian national cause.[115] As a result, Delchev was declared an ethnic Macedonian hero and a symbol of the republic. His name is referred to in the Macedonian anthem - Today over Macedonia.[116] The town of Delčevo was named after him in 1950.[60] Alongside Yane Sandanski, they became the most praised revolutionary national heroes, honored with publications and monuments. They were also portrayed as fighters against the pro-Bulgarian assimilative right-wing factions, namely the Supreme Macedonian Committee.[109][117] Macedonian school textbooks began even to hint at Bulgarian complicity in Delchev's death.[12] The economic historian Michael Palairet considers plausible that Delchev was betrayed by SMAC's members with the help of Garvanov, as Macedonian historians have asserted, but a diplomatic source reported that he was betrayed by a local peasant.[118] Aiming to enforce the belief that Delchev was an ethnic Macedonian, all documents written by him in standard Bulgarian were translated into standard Macedonian and presented as originals.[119] The claims on Delchev's Bulgarian self-identification thus were portrayed as a recent Bulgarian chauvinist attitude of long provenance.[109][120]

In the People's Republic of Bulgaria, before the late 1950s, Delchev was given mostly regional recognition in Pirin Macedonia and the town Gotse Delchev was named after him in 1950.[109][60] However, afterwards Bulgaria returned to its old policy and started vigorously denying the existence of a Macedonian nation.[109] Accordingly, orders from the highest political level of the Bulgarian Communist Party were given to reincorporate the Macedonian revolutionary movement as part of the Bulgarian historiography and to prove the Bulgarian credentials of its historical leaders.[11][109] Since 1960, there have been long unproductive debates between the ruling Communist parties in Bulgaria and SFR Yugoslavia about the ethnic affiliation of Delchev. Nonetheless, the Bulgarian side made in 1978 for the first time the proposal that some historical personalities (e.g. Delchev) could be regarded as belonging to the shared historical heritage of the two peoples, but that proposal did not appeal to the Yugoslavs.[121]

Post-communism

Delchev is regarded in Bulgaria and North Macedonia as a national hero.[122][123][124] His ethnic identity has continued to be disputed in North Macedonia, serving as a point of contention with Bulgaria.[125][126][127] Some attempts were made for the joint celebration of Delchev between both countries.[128][129] Bulgarian diplomats were also attacked when honoring Delchev by Macedonian nationalists in 2012.[130] On 2 August 2017, the Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and his Macedonian colleague Zoran Zaev placed wreaths at the grave of Delchev on the occasion of the 114th anniversary of the Ilinden Uprising.[131] Zaev expressed an interest to negotiate about Delchev.[132] A joint commission on historical issues was also formed in 2018 to resolve controversial historical readings, including the dispute about Delchev's ethnic identity, which has been unresolved.[133][134][135] On 9 October 2019, the Bulgarian government issued its "Framework Position" on the enlargement of the European Union for North Macedonia and Albania, including a condition for the joint historical commission to reach an agreement about Delchev.[136][137] The Association of Historians in North Macedonia came out against the calls for a joint celebration of Delchev, seeing them as a threat to Macedonian national identity.[138][139] Per Macedonian historian Dragi Gjorgiev, the myth of Delchev is so significant among ethnic Macedonians that it is more important than documents, books, and pieces written by historians.[140] Macedonian philosopher Katerina Kolozova opined that Bulgaria should not negotiate regarding his self-identification, seeing him as important for the national myths of Bulgaria and North Macedonia.[141] Per anthropologist Keith Brown and political scientist Alexis Heraclides, the identity of Delchev and other IMRO figures is "open to different interpretations",[142] that are incompatible with the views of modern Balkan nationalisms.[143] According to historian James Frusetta, during the time of the People's Republic of Bulgaria and SR Macedonia, the vague left populism and anarcho-socialism espoused by Delchev were transformed into overt socialism.[144]

Per journalist Reuben H. Markham, Bulgarian Macedonians have regarded him as the greatest revolutionary leader.[145] His memory has been traditionally honored by Bulgarian Macedonians.[146] There are two peaks named after Delchev: Gotsev Vrah, the summit of Slavyanka Mountain, and Delchev Vrah or Delchev Peak on Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands in Antarctica, which was named after him by the scientists from the Bulgarian Antarctic Expedition. The Goce Delčev University of Štip in North Macedonia carries his name too.[147] Many artifacts related to Delchev's activity are stored in different museums across Bulgaria and North Macedonia. During the time of SFR Yugoslavia, a street in Belgrade was named after Delchev. In 2015, Serbian nationalists covered the signs with the street's name and affixed new ones with the name of the Chetnik activist Kosta Pećanac. They claimed that Delchev was a Bulgarian and his name has no place there.[148] In 2016 the street's name was changed officially by the municipal authorities to "Maršal Tolbuhin". Their motivation was that Delchev was not an ethnic Macedonian revolutionary, but a leader of an anti-Serbian organization with a pro-Bulgarian orientation.[149][150] In Greece the official appeals from the Bulgarian side to the authorities to install a memorial plaque on his place of death are not answered. The memorial plaques set periodically by Bulgarians afterwards have been removed. Bulgarian tourists have been restrained occasionally from visiting the place.[151][152][153]

On 4 February 2023, on the 151st anniversary of the birth of the revolutionary, both the Macedonian and Bulgarian side paid their respects at the St. Spas Church in Skopje separately, while the delegation of North Macedonia declined the offer to jointly lay wreaths proposed by the Bulgarian delegation.[154] Many Bulgarian citizens who wanted to attend the event were held for hours at the border due to a claimed malfunction of the border system.[155][156] However, problems with the admission of the Bulgarians continued even after the processing of their documents.[157] As a result, many Bulgarian citizens and journalists were prevented from crossing.[158] Three citizens were detained, fined and banned from entering the country for 3 years, due to attempting to physically assault policemen.[159][160] According to their lawyer, two of them were apparently beaten.[161][162] Bulgaria officially reacted sharply to these events.[163]

Remove ads

Memorials

- Monument in Gotse Delchev, Bulgaria.

- Monument in Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria.

- Bust in Sofia, Bulgaria.

- The tomb of Gotse Delchev in the church Sv. Spas in Skopje.

- Statue of Delchev in the City Park of Skopje, given as a gift by the city of Sofia in 1946

- Monument in Strumica, North Macedonia

- Rectorate of Goce Delčev University of Štip, is located in the building of the former Bulgarian Exarchate school in which Delchev was a teacher

Remove ads

Notes

- Originally spelled in older Bulgarian orthography as Гоце Дѣлчевъ. - Гоце Дѣлчевъ. Биография. П.К. Яворовъ, 1904.

- Below is a statement that the cadet was expelled from the school on the basis of a memorandum of an officer, because of manifest poor behavior, but the school allows him to re-apply to a Commission for recovery of his status.

- "Last week the remains of the great Macedonian revolutionary Gotse Delchev were sent from Sofia to Macedonia, and from now on they will rest in Skopje, the capital of the country for which he gave his life."

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads