Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Henry Pollexfen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sir Henry Pollexfen (1632 – 15 June 1691), Counsellor at Law, of Stancombe Dawney in Sherford (near Kingsbridge), Devon, of Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, and latterly of Nutwell in the parish of Woodbury, Devon, emerged as the leading counsel of the western Assizes circuit during the 1670s and grew to more general prominence over the following decade. At a time of strong anti-Catholic feeling, he acted as counsel for the accused peers in state trials surrounding the Popish Plot allegations which emerged in 1678. He was chosen by Judge Jeffreys to present the evidence for prosecution in the Bloody Assizes following the Monmouth Rebellion, and in 1685 led the prosecution of Lady Alice Lisle. He defended the Corporation of London in the 1683 case of Quo Warranto,[1] and had a role in the Great Monopoly case of the East India Company v Sandys of 1683-85, defending Thomas Sandys.[2] Being personally of Protestant sympathies, and often advocating in resistance to the royal prerogative under the increasingly Catholic monarchs, he welcomed the departure of James II and offered advice to William of Orange in his approach and accession to the throne. For this he was rewarded by a knighthood and his appointment, in 1689, as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, during which time he also sat in Parliament. He held the office for only two years before his death in 1691.[3]

Remove ads

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

Family background

The family of Pollexfen (often pronounced "Poulson") was established of old in the coastal hinterland of south Devonshire, between the Tamar at Plymouth, and Mothecombe beside the Erme estuary, a few miles to the south-east, an area centred upon the parish of Yealmpton and the estuary of the River Yealm. Sir Henry Pollexfen himself tells in his will that his grandfather was Andrew Pollexfen of Caleston in the parish of Holbeton, gent., and that the manor of Stancombe, with property in the parishes of Sherford, Southpoole, Stokingham, Stoke Fleming and Blackawton, were the lands (spreading further eastwards) which he inherited from his ancestors.[4]

Lady Elizabeth Eliott-Drake,[5] referring to family archives, in 1911 further clarified that Sir Henry's great-grandfather was John Pollexfen of Kitley in Yealmpton, and that his father was Andrew Pollexfen (died 1670) of Stancombe Dawney in the parish of Sherford, whose wife was Joan, a daughter of John Woollcombe of Pitton in Yealmpton.[6][7] This Andrew had an elder brother Henry, of Woolston (Sir Henry's uncle), who was the senior heir, but died childless. The clarification was necessary because, contrary to the received affiliation,[8][9] Lt.Col. Vivian, in his Heraldic Visitations of Devon (1895), constructed a pedigree in which he inferred (mistakenly) from certain wills[10] that Sir Henry and his brethren were the children of the elder Henry.[11] That Henry Pollexfen of Woolston (in West Alvington) was a magistrate of many years' standing, and a notable early Quaker who was imprisoned for his beliefs in 1656: he heard George Fox's ministry at the General Meeting of Friends at Exeter in 1657, and Fox attended a large meeting for worship at his house in 1663, after which the "old Justice" accompanied him to Plymouth.[12]

Inheritance and education

Andrew Pollexfen and his wife Joan Woolcombe had three sons, Henry (the eldest, died 1691),[13] John Pollexfen, MP, the political economist (died 1715),[14] and Nicholas Pollexfen, a successful merchant (died 1682);[15] in addition they had seven daughters.[6] It is shown that Henry of Woolston planned to make his nephew Henry his heir, but on condition that Andrew should surrender to him his long lease on Stancombe Dawney, which he was reluctant to do. After a long time this was successfully arranged in August 1659 through the agency of Richard Burdwood (the younger Henry's brother-in-law), and his cousin Edmund Pollexfen of Kitley.[16] A lifetime lease of the estates was made to Andrew, which in 1666 Andrew in turn assigned to his son John in exchange for certain annuities:[17] but this arrangement lasted only until Andrew's death in 1670, whereupon the family estate passed to Henry the lawyer, as his uncle's heir.[6]

Despite his later success, Henry Pollexfen seems to have had no university education, but it is likely he received mentoring from his cousin Edmund Pollexfen whom his family referred to as the "Counsellor".[6] Edmund (later identified as "of Yealmpton") matriculated from Exeter College, Oxford on 13 February 1648/49:[18] he was admitted to Inner Temple on 15 February 1650, and Henry was admitted on 29 May 1652.[19] Edmund was called to the bar on 9 February 1656/57, and Henry on 4 November 1658: the arrangements over the estate followed soon afterwards. Similarly in 1657 Edmund handed over his rights as executor of his late father, Nicholas Pollexfen, to his mother Petronel.[20] Some sixteen years later, on 7 February 1674/75, Edmund and Henry were called to the Bench of the Inner Temple on the same day.[21] They were, in effect, almost exact contemporaries.

Contemporary, but of the next generation, was his cousin[22] the exclusionist attorney George Treby (1642-1700), also of Holbeton, who like Edmund studied at Exeter College but entered the Middle Temple. Treby's legal career (during which he sat for Plympton Erle in six parliaments between 1677 and 1692, bringing in John Pollexfen as his colleague there) ran concurrently with Pollexfen's through the great trials of that age: he became Attorney-general simultaneously with Pollexfen's appointment as Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in 1689, and after Pollexfen's death succeeded to the latter office for the term of his life.[23] Treby was on the Woolcombe side, a grandson of Phillippa (Treby), sister of Joan Woolcombe.[24]

Marriage

Having been called to the bar in November 1658,[25] by 1662 Henry was pleading before the high courts at Westminster Hall. In 1662-63, he was with Sir William Scroggs and Sir Orlando Bridgman among the Counsel for the Barber-Surgeons' Company in their petition opposing a Charter for the Physicians.[26] On 11 October 1664 he married Mary, one of the daughters of George Duncombe of Shalford, Surrey (c. 1605-1674),[27] of the Inner Temple,[28] and his wife Charity (died 1677),[29] daughter of the London alderman John Muscott. Mary's brother (Sir) Francis Duncombe (c. 1628-1670), of the Inner Temple (admitted 1647, called 1653),[30] was created 1st Baronet in 1662;[31] her brother Thomas, D.D. (c. 1633-1714), rector of Shere, Surrey 1658-1714, conducted Mary's marriage in his parish church of St James.[32] These were grandchildren of George Duncombe (1572-1646) of Weston in the parish of Albury,[33] steward of the manor of Bramley, and his wife Judith Carrill,[34] whose circle of kin with the Aungier and Onslow families was closely tied to the legal profession, within the sphere of the Mores of Loseley. By tripartite indentures Henry settled upon his intended marriage the manor, capital messuage, and the demesnes of Stancombe Downey in Devon.[35]

Walbrook House

The Pollexfen family long owned a splendid London residence at Walbrook House, adjacent to the churchyard of St Stephen Walbrook. The mansion which stood before the great fire of 1666 was reportedly inhabited by at least four knightly members of the old Devonian family.[36] The house was so close to the (original) church that the family vault actually lay under the dwelling-house, as shown in verses inscribed on a stone:

"Who lies heere? Why, don't e ken?

The family of Pollexfen;

Who, bee they living or bee they dead,

Like theirre own house over theirre head,

That, whener theirre Saviour comme,

They allwaies may bee found at homme."[36]

The house was rebuilt (from 1668) by Henry's brother John Pollexfen[37][38] (before Christopher Wren rebuilt the church at its new site), in a position further back from the street than formerly, so that it stood on a foundation or basement of "lofty brick arches of exquisite workmanship and great antiquity". To the writer of 1795 this suggested the remains of a former religious house on the site,[36] but since the discovery of the Walbrook Mithraeum in 1954 a Roman origin for these arches (now lost) may seem possible. After the mansion's rebuilding, the vault remained, underground, but now extended partly under the courtyard in front of the new mansion, which had "an elegant and most correct front of the Corinthian order", a beautiful carved staircase, and niches with statuary.[36] Walbrook House was the London residence of John Pollexfen, who gave the parish "a spot of land to make the building [i.e., the church] uniform":[36] the mansion was presumably standing when Pollexfen complained to the Court of Aldermen that Wren's proposed church plan would seriously obstruct his lights, and (with the help of his father-in-law Sir John Lawrence) the matter was adjusted.[39]

Remove ads

Legal practice

Summarize

Perspective

Pollexfen's own collected Reports commence in 1669/1670. In February 1674/75 he became a bencher at Inner Temple,[21] and was the leading practitioner on the western circuit, frequently pleading at the King's Bench. In 1676 he defended Stockbridge, Hampshire on a Quo Warranto charge, which he lost. He frequently acted as counsel in various politically charged cases, and regularly lost.

The "Popish plot", 1678-1684

During the 1670s a tide of anti-Catholic feeling broke violently in the allegations, made by Titus Oates in 1678, of a supposed conspiracy (the "Popish Plot") among leading Catholics to assassinate King Charles II. Among the trials and executions which resulted, Pollexfen was assigned as counsel to one of the accused Catholic lords, Henry Arundell, 3rd Baron Arundell of Wardour. The law did not at that time allow a formal defence in cases of Treason, and although Arundell's arraignment and impeachment were deferred he remained in prison until 1684. Pollexfen acted for the Catholic John Tasborough, who was tried and convicted in February 1679/80 for inciting one of the principal witnesses to withdraw his evidence.[40][41] Meanwhile, in 1679 he also advised the Earl of Danby (who had first announced the Oates allegations to Parliament, and was now accused of having concealed his knowledge of them) to plead his pardon, which he did:[8] parliament, however, insisted that a royal pardon was no defence against impeachment by the Commons, and Osborne remained in prison until 1685.

As the falsity of the Plot allegations became known, prosecution turned against the inciters. Pollexfen was one of many counsel for Edward Fitzharris (1681),[42] Stephen College and Algernon Sidney (1683),[43] all of whom were later executed: he was among the counsel for William Russell, Lord Russell (executed at Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1683). In this context Roger North (1653-1734) said of him, that "he was the adviser and advocate of all those that were afterwards found traitors."[44]

In October 1682 Henry and John Pollexfen, as executors, swore to administer the will of their brother Nicholas, who left bequests to his widow and married sisters, and £100 towards the foundation of a working almshouse in the City of London.[15] A year later, Henry was chosen Reader at the Inner Temple.[45]

Corporations

The opinion arose that "his reputed tendencies were in opposition to the court", and that he stood against the crown and monarchy.[8][44] In several important cases, Pollexfen counselled on behalf of Corporations, arguing that they could not be charged for the wrongdoing of individuals. With Sir George Treby and Sir Francis Winnington he defended London on a second Quo Warranto brought against it by the Crown in 1683.[46][47][48] He lost, and this encouraged the Crown to make attacks on the Charters of Corporations throughout the kingdom, whose liberties empowered them to nominate jurors under a sheriff, with considerable political implications. He notably counselled for the defence of William Sacheverell, tried in 1684 for inciting a riot over the surrender of the Charter of the city of Nottingham.[49] In 1684 he was asked to take a similar case for Berwick-upon-Tweed, this time advising surrender. At this time he also defended Thomas Sandys, in the monopoly case brought by the British East India Company against him for having traded a cargo of textiles out of India into the Thames.[2]

Richard Baxter, 1685

In November 1684 Thomas Rosewell, a dissenting teacher, went on trial for High Treason for words he had spoken when preaching at a conventicle. Although Rosewell was convicted, Sir John Talbot conferred with King Charles, who in an arrest of judgement assigned Pollexfen and two others to act as counsel to Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys, to argue the insufficiency of the indictment (which Jeffreys had refused to provide to the defendant in written form).[50] While that was considered, the King granted Rosewell a pardon, and he was later discharged.[51]

The leading Nonconformist minister Richard Baxter (1615-1691), a devout and moderate man, was brought to trial in 1685 on the charge of libelling the Church of England in his Paraphrase on the New Testament. The object was to intimidate dissenters at large, among whom the Whig tendency was strongly rooted. Sir Henry Ashurst, 1st Baronet (1645-1711), of Waterstock,[52] (like his father, a close personal friend of Baxter's) paid for a defence led by Pollexfen with five supporting counsel, and stood beside the prisoner throughout. Baxter was committed to the King's Bench prison in February, arraigned at Westminster Hall during May and tried before Lord Chief Justice George Jeffreys beginning the 30th of that month at the London Guildhall.

Of the proceedings no official record was printed, the short version appearing in State Trials (which does not mention Pollexfen among the defending counsel) being copied from Edmund Calamy's Abridgement of Baxter's History of his Life and Times.[53] However a letter by a witness present at the trial, sent as information to Matthew Sylvester,[54] if accepted, paints a much fuller picture of the extraordinary behaviour of Judge Jeffreys, who in the most vulgar and savage way railed at the prisoner and his counsel alike, barely permitting them to present their defence. This source, supported by other documentation, shows that Pollexfen's statements, though curtailed by Jeffreys, were well and patiently attempted. Baxter was found guilty, but by the intercession of the bishop of London his sentence was commuted to a £500 fine and a conduct bond of seven years.[55]

The "Bloody Assizes", 1685

Following the Monmouth Rebellion, Henry Pollexfen was assigned by Sir Robert Sawyer, the King's Attorney, to conduct the prosecution of rebels in the West Country before Judge Jeffreys, whom he had so recently confronted in the Baxter case. From August to November 1685 the "Bloody Assizes", so named for the many death sentences handed down, were visited with exceptional severity upon the common people little able to defend themselves. One commentator related that Pollexfen ("an ill-natured, surly, but great lawyer") sent his agent to encourage many of them to plead guilty in the hope of mercy, whereupon the judge condemned them wholesale.[56] His role in these prosecutions, against an uprising provoked by the King's catholicism, surprised some who had admired his championing of liberties: but whether he exceeded his formal responsibility of presenting evidence, differing opinions are given.[8][44] In 1685 he led the prosecution, for the King, in the trial of Dame Alice Lisle for High Treason, whereby she was convicted, attainted and executed for having shown hospitality to a nonconformist minister who was later found to have been a partizan of the Duke of Monmouth.[57] It should not be supposed, however, that Pollexfen was in any position to refuse the royal writ to conduct the prosecutions, nor that he was personally responsible for the savagery of the punishments.[58]

The Seven Bishops, 1688

Under his counsel, in 1688 Sir Patience Ward pleaded pardon for perjury. In that year Pollexfen argued part of the defence in the trial of the Seven Bishops.[59] Foss expresses it well: "on the trial of the seven bishops in June 1688, he was offered a retainer on their behalf, which he refused to accept unless Mr Somers were associated with him. This being reluctantly conceded, as the bishops thought Somers too young and inexperienced, Pollexfen exerted himself zealously for his reverend clients, and Somers justified the recommendation of his discriminating patron, by the effective assistance he afforded."[8] In this way the Lord Somers stepped onto the threshold of his coming power.

High office, 1688-1691

Pollexfen's sympathies lay with the whiggish, Protestant faction. After William III arrived in 1688 he was a close advisor, and encouraged him to declare himself King, arguing that the throne was vacant because James had fled, and that James 'went away because the terror of his own conscience frighted him and he durst stay no longer'.[3] William sought a more judicious path to the throne. Even so, Pollexfen's contribution to the debate and settlement of the succession issue was considerable, and his promotion to high office was both suitable and expedient to the new reign.

In December 1688, the Lords called upon five senior lawyers (of whom he was one) to attend them, to consult on how to proceed in the present juncture, and how they should legitimately summon a parliament.[60] In January 1688/89 he was returned as Member of Parliament for Exeter in the 1689 Convention Parliament. After much deliberation as to how the vacancy of the Crown had arisen, and upon what terms William might assume sovereign powers together with Queen Mary II, the Commons (whom Pollexfen addressed frequently and at length) carried the day, and William was officially offered the crown.[13]

In February Pollexfen received his appointment as Attorney General for England and Wales,[60] and on 5 March he was knighted[61] in recognition of his services. Having taken his oath as serjeant-at-law amid ceremonies at Gray's Inn, Westminster and Fleet Street, he was appointed Chief Justice of the Common Pleas on 6 May 1689,[60] and his cousin Treby took his place as Attorney-general. He swiftly obtained the special admission of his son Henry to the Inner Temple.[62] In his first days in his new office he overstepped the mark, and was summoned before the Lords for breach of priviledge for having turned the Duke of Grafton out of his Treasury office of the Common Pleas.[60] With John Holt, Lord Chief Justice of the other Bench, he approved the Ordinances of the Worshipful Company of Grocers.[63]

Before his death, Pollexfen compiled, revised and annotated a volume of his own Arguments and Reports in some special cases, together with various of his decrees in Chancery relating to limitations of trusts. This was published posthumously in 1702 with official approval.[64] Edward Foss remarked that his Reports "are not held in any great repute."[8] Roger North claimed that Pollexfen, in his Preface to this work, "most brazenly and untruly" declared, concerning a particular case he had lost, that "he had carried the cause, if the Lord Keeper North had not solicited the judges to give a contrary judgement": but, upon this being shown to Lord Chief Justice Holt, the bookseller was called to account for it, and had to remove the words or face the suppression of the whole edition.[65]

Remove ads

Death

Summarize

Perspective

Lady Eliott-Drake provides a circumstantial account of Pollexfen's last days. He served as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas for only two years. Having mostly withdrawn from Nutwell in the parish of Woodbury, Devon, which he had bought in 1685, Sir Henry and Dame Mary lived mainly at their mansion in Lincoln's Inn Fields (apparently on the south side, in Portugal Row)[66] or at Hampstead, where they had a country house with large gardens.[67] The marriage of their eldest daughter Elizabeth (with a dowry of £5000) to Sir Francis Drake, 3rd Baronet (1642-1718) took place at St Clement Danes in February 1689/90,[68] and on 9 June 1691 Elizabeth's sister Mary was married to John Buller in the church at the Drakes' seat at Buckland Monachorum in Devon: the Buller home was to be at Keverall, near Morval. However, the day after the wedding Sir Henry was called back to London, and the exertion of the wedding followed by the three-days' journey proved too much for him. Arriving in London he had a burst blood vessel and haemorrage, and died at his home on 15 June 1691. The news of his illness was slow to reach Devon, where Dame Mary set off at once upon hearing of it, but arrived home to find him dead.[69]

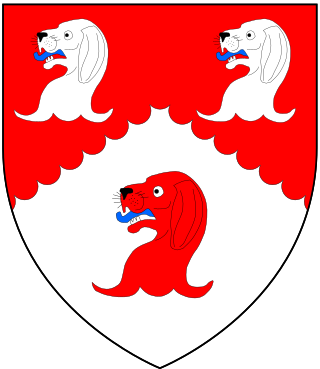

His funeral arrangements were made by his brother John Pollexfen. He lay in state in London in a lead coffin enclosed within a velvet-covered casing decorated with heraldic devices, in a room draped with black cloth. His body was then taken back to Devon, to Nutwell, in the care of his confidential clerk, and on 3 July 1691 he was buried with great ceremony at Woodbury church, in a vault beneath the altar.[70] His memorial slab bore, beneath an oval cartouche displaying his arms, the following inscription:

"Underneath Lyes the dust of Sir Henry Pollexfen Kt, Lord Chief Justice of ye Comon Pleas Who for his exemplary Integrity & eminent knowledge of ye Learning of ye Laws, Liv'd highly esteemed and Dy'd greatly Lamented. Being a Real Ornament to the Court wherein he sate, to his Country and ye Age he liv'd in. He departed this life ye 15 day of June 1691, in ye 59 year of his age."

His widow Dame Mary, having given up her family home at Hampstead, removed to Lincoln's Inn Fields but fell into various difficulties.[71] She finally returned to Shalford in Surrey, made her will,[72] and, dying 31 January 1694/95, was buried in her father's grave at Shalford church, where she had a white marble wall-plaque inscribed with Latin and English verses composed by her brother Anthony Duncombe.[73] The continuing story of the Pollexfen offspring and their descent in the Drake and Duncombe families is resumed by Lady Eliott-Drake in her ensuing chapters.[74]

Remove ads

Family

Summarize

Perspective

Sir Henry Pollexfen married Mary Duncombe, a daughter of George Duncombe of Shalford (c. 1605-1677) and his wife Charity, née Muscott (died 1677), at Shere, Surrey, on 11 October 1664.[32] They had issue one son and four daughters, as follows:[13][11]

- Henry Pollexfen (d.1732), of Nutwell, son and heir, who married Gertrude Drake (1669-1729), a daughter of Sir Francis Drake, 3rd Baronet (1642-1718) of Buckland Monachorum in Devon, by his first wife Dorothy Bampfylde, a daughter of Sir John Bampfylde, 1st Baronet[75] of Poltimore, Devon. He died childless, leaving his four sisters as his co-heiresses. Nutwell eventually passed to the Drake family, through his sister Elizabeth Pollexfen.

- Elizabeth Pollexfen (c. 1669-1717), heiress of Nutwell, who in 1689 married (as his third wife) Sir Francis Drake, 3rd Baronet (1642-1718) of Buckland Monachorum, her brother's father-in-law. She was the mother of Sir Francis Drake, 4th Baronet (1694–1740).

- Mary Pollexfen (c. 1670-1722), who married John Buller (1668–1701) of Keverell in Cornwall, a member of parliament for Lostwithiel in Cornwall in 1701,[11][76] only son and heir apparent of John Buller (1632–1716), MP, of Morval and of Shillingham near Saltash, both in Cornwall.

- Anne Pollexfen, who married George Duncombe of Shephill in Surrey, her mother's great-nephew;[31]

- Jane Pollexfen, who married Capt. Francis Drake (1668-1729), Royal Navy (first cousin of the 3rd Baronet), whose monument survives in St Andrew's Church in Plymouth.[77]

Remove ads

Sources

- Crossette, J.S., 'Pollexfen, Henry (c.1632-91), of Woodbury, Devon and Lincoln's Inn Fields, London', in B.D. Henning (ed.), History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660–1690 (1983), History of Parliament Online.

- Eliott-Drake, E.,[5] The Family and Heirs of Sir Francis Drake, 2 vols (Smith, Elder, & Co., London 1911), II, pp. 55–86 (Internet Archive).

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads