Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Initial Teaching Alphabet

Aid for teaching English reading From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA or i.t.a.) is a variant of the Latin alphabet developed by Sir James Pitman (the grandson of Sir Isaac Pitman, inventor of a system of shorthand) in the early 1960s. It was not intended to be a strictly phonetic transcription of English sounds, or a spelling reform for English as such, but instead a practical simplified writing system which could be used to teach English-speaking children to read more easily than can be done with traditional orthography. After children had learned to read using ITA, they would then eventually move on to learn standard English spelling. Although it achieved a certain degree of popularity in the 1960s, it has fallen out of use since the 1970s.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2010) |

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

In 1959, the Conservative MP James Pitman initially promoted the ITA as a stepping stone to full literacy.[1] The idea was that children would switch to the conventional alphabet after a few years.[1]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the ITA was used in some schools in England:[1] "By 1966, 140 of the 158 UK education authorities taught ITA in at least one of their schools."[1] Some other English-speaking countries used it too.[1] It is not clear why it was taught only in some schools, or to some groups of children in particular schools.[1]

Since ITA was not formally introduced as an academic standard in the UK or anywhere else, it is not clear when it fell out of use, but it appears to have faded away by the end of the 1970s.[2]

Any advantage of the ITA in making it easier for children to learn to read English was often offset by some children not being able to effectively transfer their ITA-reading skills to reading standard English orthography, or being generally confused by having to deal with two alphabets in their early years of reading. Certain alternative methods (such as associating sounds with colours, so that for example when the letter "c" writes a [k] sound it would be coloured with the same colour as the letter "k", but when "c" writes an [s] sound it could be coloured like "s", as in Words in Colour and Colour Story Reading[3]) were found to have some of the advantages of the ITA without most of the disadvantages.[4][5]

Although the ITA was not originally intended to dictate one particular approach to teaching reading, it was often identified with phonics methods, and after the 1960s, the pendulum of educational theory swung away from phonics. The ITA was very rarely used by the 1970s.[2]

Remove ads

Details

Summarize

Perspective

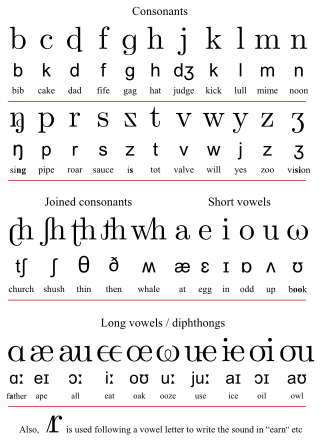

The ITA originally had 43 symbols, which was expanded to 44, then 45. Each symbol predominantly represented a single English sound (including affricates and diphthongs), but there were complications due to the desire to avoid making the ITA needlessly different from standard English spelling (which would make the transition from the ITA to standard spelling more difficult), and in order to neutrally represent several English pronunciations or dialects. In particular, there was no separate ITA symbol for the English unstressed schwa sound [ə], and schwa was written with the same letters used to write full vowel sounds. There were also several different ways of writing unstressed [ɪ]/[i] and consonants palatalized to [tʃ], [dʒ], [ʃ], [ʒ] by suffixes. Consonants written by double letters or "ck", "tch" etc. sequences in standard spelling were written with multiple symbols in the ITA.

The ITA symbol set includes joined letters (typographical ligatures) to replace the two-letter digraphs "wh", "sh", and "ch" of conventional writing, and also ligatures for most of the long vowels. There are two distinct ligatures for the voiced and unvoiced "th" sounds in English, and a special merged letter for "ng" resembling ŋ with a loop. There is a variant of the "r" to end syllables, which is silent in non-rhotic accents like Received Pronunciation but not in rhotic accents like General American and Scots English (this was the 44th symbol added to the ITA).

There are two English sounds which each have more than one ITA letter whose main function is to write them. So whether the sound [k] is written with the letters "c" or "k" in ITA depends on the way the sound is written in standard English spelling, as also whether the sound [z] is written with the ordinary "z" letter or with a special backwards "z" letter (which replaces the "s" of standard spelling where it represents a voiced sound, and which visually resembles an angular form of the letter "s"). The backwards "z" occurs prominently in many plural forms of nouns and third-person singular present forms of verbs (including is).

Each of the ITA letters has a name, the pronunciation of which includes the sound that the character stands for. For example, the name of the backwards "z" letter is "zess".

A special typeface was created for the ITA, whose characters were all lower case (its letter forms were based on Didone types such as Monotype Modern and Century Schoolbook). Where capital letters are used in standard spelling, the ITA simply used larger versions of the same lower-case characters. The following chart shows the letters of the 44-character version of the ITA, with the main pronunciation of each letter indicated by symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet beneath:

Note that "d" is made more distinctively different from "b" than is usual in standard typefaces.

Later a 45th symbol was added to accommodate accent variation, a form of diaphonemic writing. In the original set, a "hook a" or "two-storey a" (a) was used for the vowel in "cat" (lexical set trap), and a "round a" or "one-storey a" (ɑ) for the sound in "father" (lexical set palm). But lexical set bath (words such as "rather", "dance", and "half") patterns with palm in some accents including Received Pronunciation, but with trap in others including General American. So a new character, the "half-hook a", was devised, to avoid the necessity of producing separate instructional materials for speakers of different accents.

A series of international ITA conferences were held, the fourth being in Montreal in 1967.[6]

Remove ads

Academic research on ITA

Summarize

Perspective

After the implementation of ITA, research was conducted to study its effect on children's learning.

In 1960, the University of London Institute of Education and the National Foundation for Educational Research in England and Wales began a 6-year investigation into the initial teaching alphabet. The investigation found that using ITA is clearly superior to traditional orthography in the initial stages of learning. However, the research results are less clear with regard to the effectiveness of ITA in transfer to traditional orthography.[7]

Another research paper published in 1966 showed that the value of the ITA as a symbol system to be incorporated into speech therapy seemed promising.[8]

A quantitative research study compared teaching in ITA compared to traditional orthography in the first grade in the Pittsburgh public schools in 1966. It showed superior achievement for ITA students. However, the researchers also cautioned that their results were restricted to the first year and it was unclear whether ITA students could retain the advantage later.[9]

In 1974, a quantitative study on students' spelling was conducted for grades 3, 4, and 5 in a rural area in western New York. The study found no significant difference in spelling achievement between ITA and traditional typography students. The study concluded that "the evidence obtained from the spelling attempts of the children who were taught the initial teaching alphabet tends to show that little would be gained from teaching patterns of sound-to-symbol generalizations."[10]

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Some adults who were taught with ITA when they were children felt that they had been disadvantaged, as they remain poor spellers, while some teachers have thought that it had been successful for some children.[1]

Professor Dominic Wyse at University College London, who led a study in 2022 on teaching children to read, suggested that contextualized teaching of reading is more effective than using synthetic phonics. The study argued that the British government should not have direct control over the curriculum, but should instead devote the matter to professional judgement of teachers.[11] While the study is not specific to ITA, he thinks ITA is regarded as an experiment that didn’t work due to difficulty in transition to the standard alphabet. Professor Rhona Stainthorp, a professor of literacy at the University of Reading, believes that ITA is "a perfect example of someone thinking they’ve got a good idea and trying to simplify something, but having absolutely no idea about teaching."[1]

The ITA remains of interest in discussions about possible reforms of English spelling.[12] There have been attempts to apply the ITA using only characters which can be found on the typewriter keyboard[13] or in the basic ASCII character set, to avoid the use of special symbols.

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads