Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

James Cook

British explorer and naval officer (1728–1779) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Captain James Cook (7 November 1728[a] – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer who led three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans between 1768 and 1779. He completed the first recorded circumnavigation of the main islands of New Zealand, and led the first recorded visit by Europeans to the east coast of Australia and the Hawaiian Islands.

Cook joined the British merchant navy as a teenager before enlisting in the Royal Navy in 1755. He first saw combat during the Seven Years' War, when he fought in the Siege of Louisbourg. Later in the war he surveyed and mapped much of the entrance to the St. Lawrence River during the Siege of Quebec. In the 1760s he mapped the coastline of Newfoundland and made important astronomical observations which brought him to the attention of the Admiralty and the Royal Society. This acclaim came at a pivotal moment in British overseas exploration, and it led to his commission in 1768 as commander of HMS Endeavour for the first of his three voyages.

During these voyages he sailed tens of thousands of miles across largely uncharted areas, mapping coastlines, islands, and features across the globe in greater detail than previously charted – including Easter Island, Alaska, and South Georgia Island. He made contact with numerous indigenous peoples, and claimed several territories for the Kingdom of Great Britain. Renowned for exceptional seamanship and courage in times of danger, he was patient, persistent, sober, and competent, but sometimes hot-tempered. His contributions to the prevention of scurvy, a disease common among sailors, led the Royal Society to award him the Copley Gold Medal.

In 1779, during his second visit to Hawaii, Cook was killed when a dispute with Native Hawaiians turned violent. His voyages left a legacy of scientific and geographical knowledge that influenced his successors well into the 20th century. Numerous memorials have been dedicated to him worldwide.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

James Cook was born on 7 November 1728[a] in the village of Marton, located in the North Riding of Yorkshire, approximately 8 miles (13 km) from the sea.[2] He was the second of eight children of James Cook, a Scottish farm labourer from Ednam in Roxburghshire, and his wife, Grace Pace, from Thornaby-on-Tees.[3] In 1736, his family moved to Airey Holme farm at Great Ayton, where his father's employer, Thomas Skottowe, paid for Cook to attend a school run by a charitable foundation.[4] In 1741, after five years of schooling, he began work for his father who had been promoted to farm manager.[5]

In 1745, when he was 16, Cook moved 20 miles (32 km) to the fishing village of Staithes to be apprenticed as a shopboy to grocer and haberdasher William Sanderson.[6] After 18 months, Cook, proving not suited for shop work, travelled to the nearby port town of Whitby and was introduced to Sanderson's friends John and Henry Walker. The Walkers were prominent local ship-owners in the coal trade.[7]

Cook was taken on as a merchant navy apprentice in the Walkers' small fleet of vessels, plying coal along the English coast. His first assignment was aboard the collier Freelove, and he spent several years on this and various other coasters, sailing between the Tyne and London. As part of his apprenticeship, Cook applied himself to the study of algebra, geometry, trigonometry, navigation and astronomy – all skills needed to command a ship.[8]

Upon completing his three-year apprenticeship, Cook began working on merchant ships in the Baltic Sea. After obtaining his mariner licence in 1752 he was promoted to the rank of mate and began serving on the collier brig Friendship.[9] He served as mate on the Friendship for two and a half years, visiting ports in Norway and Netherlands, learning to navigate in shallow waters along the east coast of Britain, and traversing the Irish Sea and the English Channel.[10]

Remove ads

Royal Navy

Summarize

Perspective

At the age of 26, Cook was offered a promotion to captain of Friendship, but he declined and instead joined the Royal Navy at Wapping on 17 June 1755.[11][b] He entered the navy when Britain was expanding its naval forces in anticipation of the conflict that became known as the Seven Years' War.[13] Cook's first posting was two years aboard HMS Eagle, serving as able seaman and master's mate under Captain Joseph Hamar and, later, Captain Hugh Palliser.[13] In October and November 1755 he took part in Eagle's capture of one French warship and the sinking of another. Following the death of Eagle's boatswain, Cook was unofficially promoted to fill that role in January 1756.[14] His first command was in March 1756 when he was briefly in charge of Cruizer, a small cutter attached to Eagle.[15] In June 1757, Cook passed his master's examinations at Trinity House, Deptford, qualifying him to navigate and handle a ship of the King's fleet.[16][c] He then joined the sixth-rate frigate HMS Solebay as ship's master under Captain Robert Craig.[17]

Seven Years' War

During the Seven Years' War, Cook served in North America as master aboard the fourth-rate Navy vessel HMS Pembroke.[19] With others in Pembroke's crew, he took part in the major amphibious assault that captured the Fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia from the French in 1758.[20]

The day after the fall of Louisbourg, Cook met an army officer, Samuel Holland, who was using a plane table to survey the area.[21] The two men had an immediate connection through their interest in surveying, and Holland taught Cook the methods he was using.[22] They collaborated on developing preliminary charts of the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River, with Cook writing the accompanying sailing directions.[23] Cook's first map to be engraved and printed was of Gaspé Bay, drawn in 1758 and published in 1759.[18] The integration of Holland's land-surveying techniques with Cook's hydrographic expertise enabled Cook, from that point forward, to produce nautical charts of coastal regions that significantly exceeded the accuracy of most contemporary charts.[24]

As Major-General James Wolfe's advance on Quebec progressed in 1759, Cook and other ships' masters took soundings, marked shoals, and updated charts – particularly around Quebec. This information enabled Wolfe to mount a stealthy nighttime attack by transporting troops across the river, leading to victory in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.[25]

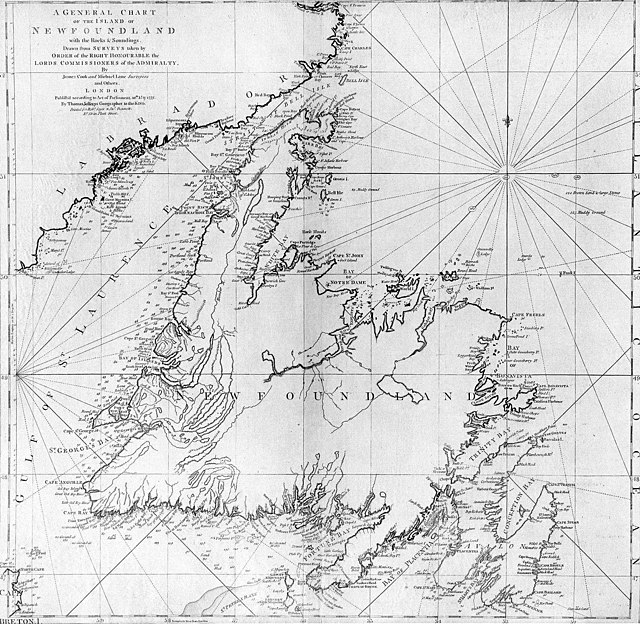

Newfoundland

As the Seven Years' War came to a close, Cook was tasked with charting the rugged coast of Newfoundland.[27] He was appointed master of HMS Grenville, and spent five seasons producing charts.[28][d] He surveyed the north-west stretch in 1763 and 1764, the south coast between the Burin Peninsula and Cape Ray in 1765 and 1766, and the west coast in 1767.[30] Cook employed local pilots to point out the rocks and hidden dangers.[30]

Cook severely injured his right hand in August 1764 when a powder horn he was carrying exploded.[31][e] In July 1765, Cook experienced the first of several ship groundings he faced during his career: Grenville struck an uncharted rock, and cargo had to be unloaded before she could be refloated.[33]

While in Newfoundland, Cook precisely recorded apparent (or local) time of the start and end of the solar eclipse of 5 August 1766. He sent the results to the English astronomer John Bevis, who compared them with the same data from an observation of the eclipse carried out in Oxford and calculated the difference in longitude between the two locations.[34] The results were communicated to the Royal Society in 1767 and the longitude position obtained was used by Cook in his printed sailing directions for Newfoundland.[35][f]

At the end of the 1767 surveying season, while HMS Grenville was returning to her home port of Deptford, Cook encountered a storm at the entrance to the Thames. He anchored Grenville off the Nore lighthouse and prepared the ship to ride out the weather. An anchor cable snapped, causing the ship to run aground on a shoal. Despite efforts to refloat her, Cook and his crew were forced to abandon ship. They returned when the storm abated, lightened and rerigged the ship, and continued into Deptford.[37]

Exploration of the Pacific Ocean

Cook's achievements in North America – hydrographic and astronomical – were noticed by the Admiralty, and came at a pivotal moment in British overseas exploration.[39] Europeans had started exploring the Pacific Ocean in the early 16th century, and by the mid-18th century they had charted much of the ocean's perimeter, and were actively engaged in trade with the Philippines, Spice Islands, and Mexico.[40] Yet vast regions of the ocean remained largely unexplored by Europeans, including the coastlines of Canada and Alaska, much of the southern Pacific, and the central oceanic expanse. Several major questions persisted:[41] Did a North-West Passage connect the North Pacific with the North Atlantic?[42] Did the hypothesised continent of Terra Australis Incognita (undiscovered southern land) exist?[43] And were there yet-undiscovered cultures or lands in the central Pacific?[44]

The Treaty of Paris – signed when the Seven Years' War ended in 1763 – enabled the Royal Navy to redirect resources from warfare to exploration.[45] Britain soon dispatched several explorers to the Pacific Ocean, including John Byron, Samuel Wallis, and Philip Carteret.[46] They returned with accounts of Tahiti, and reported sightings of Terra Australis[g] – setting the stage for Cook's first voyage.[47]

Remove ads

First voyage (1768–1771)

Summarize

Perspective

Cook's first scientific voyage was a three-year expedition to the south Pacific Ocean aboard HMS Endeavour, conducted from 1768 to 1771. The voyage was jointly sponsored by the Royal Navy and Royal Society.[50] The publicly stated goal was to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from the vantage point of Tahiti.[51][h] Additional objectives – outlined in secret orders – were searching for the postulated Terra Australis and claiming lands for Britain.[54][i]

In early 1768, the Admiralty asked the shipwright Adam Hayes to select a vessel for the expedition; he chose the merchant collier Earl of Pembroke, which the Royal Navy renamed Endeavour.[56][j] On 5 May 1768 – based on the recommendation of Hugh Palliser – Cook, aged 39, was selected by the Admiralty to lead the voyage.[59][k] The next day he took his examination for the rank of lieutenant – a rank which was required to command a ship armed with the number of guns planned for Endeavour.[61]

Like most colliers, Endeavour had a large hold, a sturdy construction that would tolerate grounding, was small enough to be careened (laid on her side for repairs), and had a shallow draught that enabled navigating in shallows.[62] Upon completion of the first voyage, Cook wrote: "It was to these properties in her, those on board owe their Preservation. Hence I was enabled to prosecute Discoveries in those Seas so much longer than any other Man ever did or could do."[63] When selecting ships for his second voyage in 1772, Cook chose the same type of ship, from the same shipbuilder.[64]

The Admiralty authorised a ship's company of 73 sailors and 12 marines.[65] Cook's second lieutenant was Zachary Hicks, and his third lieutenant was John Gore, a 16-year naval veteran who had already circumnavigated the world twice aboard HMS Dolphin.[66] Also on the ship were astronomer Charles Green and 25-year-old naturalist Joseph Banks.[67] Banks provided funding for seven others to join the journey: the naturalists Daniel Solander and Herman Spöring, the artists Alexander Buchan and Sydney Parkinson, two black servants, and a secretary.[68]

Tierra del Fuego

The expedition departed England on 25 August 1768 and headed south to round Cape Horn into the Pacific.[69] They made a stop in Tierra del Fuego, where Cook composed his first anthropological essay, detailing his observations of the indigenous Haush people.[70] Banks went ashore with several members of his party to collect botanical specimens. During the overnight excursion, his two black servants, Thomas Richmond and George Dorlton, froze to death.[71]

Tahiti

The ship continued westward across the Pacific, arriving at Tahiti on 13 April 1769, where the observations of the transit of Venus were made.[72][l] In May, Cook and some of his crew observed Tahitians surfing – becoming the first Europeans to witness the practice.[75]

In June, two incidents happened that recurred in various forms throughout Cook's voyages: Tahitians were offended when some of his crew took rocks – to use as ship's ballast – from a sacred marae without permission.[76] In a separate event, Tahitians took various items from the crew, prompting Cook to seize 22 canoes – many of which did not belong to the individuals responsible – as ransom until the stolen property was returned.[76]

In July, two marines deserted by taking local wives and going into hiding, intending to remain on the island. In response, Cook detained a Tahitian chief as a hostage to compel the local community to locate and return the deserters.[78] Cook then sailed from Tahiti to the nearby island of Huahine, then to Raiatea where he claimed Raiatea-Taha'a and the islands of Huahine, Borabora, Tupai, and Maupiti for Britain, naming them the Society Islands.[79]

New Zealand

As directed by his secret orders, Cook began his search for the postulated southern continent of Terra Australis.[80] He sailed to New Zealand and – in October 1769 – landed at Poverty Bay near the Tūranganui River.[81] With the aid of Tupaia, a Tahitian priest who had joined the expedition, Cook was the first European to communicate with the Māori.[82] However, encounters with them on the first two days turned violent, the British shooting several dead.[83] Cook's approach to interactions with the Māori was to offer greetings and exchange gifts, in an attempt to establish friendly relations. But if his crew was threatened, he often ordered a quick and decisive use of force, despite his instructions from the Royal Society.[84]

Sailing north, Endeavour anchored at Mercury Bay on 9 November where Cook observed the transit of Mercury and claimed the bay for Britain.[85] In January 1770, Cook arrived in Queen Charlotte Sound, on the north coast of New Zealand's South Island. He claimed the location for Britain and it became a favourite base for his future voyages. While there, Cook came upon Māori eating the flesh of enemies they had recently killed, which confirmed stories of cannibalism his crew had heard in Poverty Bay.[86] Cook established that a strait separated the North Island from the South Island and then completed the circumnavigation of New Zealand's main islands, mapping almost the complete coastline.[87]

Australia

Convinced that no unknown southern continent existed in those latitudes, Cook continued west.[90] On 19 April 1770, Point Hicks was sighted, and the crew became the first Europeans to encounter Australia's eastern coastline.[49][n] Endeavour continued northwards along the coastline, keeping the land in sight, while Cook charted and named landmarks along the way.[91] During this stretch, Cook saw several Aboriginal Australians on shore, but was unable to draw close enough to make contact.[92]

On 29 April they made their first landfall on the continent in Botany Bay.[93] In the expedition's first direct encounter with Aboriginal Australians, two Gweagal men opposed the landing and in the following confrontation one warrior was wounded with small shot.[94] Cook and his crew stayed at Botany Bay for a week, exploring the surrounding area and collecting water, timber, fodder, and botanical specimens.[95] Cook attempted to establish relations with the Aboriginal people but concluded that they only wanted the British to leave.[96][o]

After departing Botany Bay they continued northwards, hugging the coast and charting it.[99] They stopped at Bustard Bay in May 1770, then proceeded north through the shallow and extremely dangerous Great Barrier Reef.[100] On 11 June Endeavour ran aground on the reef at high tide.[101] The ship was stuck fast, so Cook ordered all excess weight thrown overboard, including six cannons. She was eventually hauled off after 27 hours.[102] The ship was leaking badly, so the crew fothered the damage (hauling a spare sail under the ship to cover and slow the leak).[103] Cook then careened the ship on a beach at the mouth of the Endeavour River for seven weeks while repairs were made.[104]

The crew explored the surrounding area, where Cook observed a kangaroo for the first time. One was killed and the species was documented by Banks.[105] The local Guugu Yimithirr people generally avoided the British, although following a dispute over green turtles Cook ordered shots to be fired and one local was lightly wounded.[106]

The expedition continued northward until they reached the north-east tip of Australia: Cape York. Cook proceeded to a nearby island where he scanned the surrounding waters for a route forward. There he claimed the entire Australian coast that he had surveyed as British territory and named the island Possession Island.[107] The expedition then turned west and continued homewards through the shallow and dangerous waters of the Torres Strait.[108]

Return to England

In October 1770, Cook stopped in Batavia (modern Jakarta, Indonesia), where the Dutch dockyard facilities were used to inspect and repair the damage from running aground on the Great Barrier Reef.[109] After departing Batavia in late December 1770, the expedition sailed to the Cape of Good Hope, then to the island of Saint Helena, arriving on 30 April 1771.[110]

The stay in Batavia marked the onset of the most severe outbreak of illness and death endured during any of Cook's voyages: seven crew members died in Batavia, and a further 23 perished on the return journey to England.[111] The majority of the deaths were caused by dysentery (with some attributed to tuberculosis and possibly typhoid fever) often worsened by malaria.[112][p]

The ship finally returned to England on 12 July 1771, anchoring in the Downs.[114] In August, Cook was promoted to the rank of commander.[115] A book about the voyage, based on the journals of Cook and Banks, was published in 1773.[116]

Remove ads

Second voyage (1772–1775)

Summarize

Perspective

In 1772, Cook was commissioned to lead a second scientific expedition on behalf of the Royal Society, with the objective of determining the existence of the hypothetical continent Terra Australis.[117] Cook created a plan to probe southward in the southern summer, then retreat to more northerly, warmer, regions in the frigid southern winter.[118]

This voyage would have two ships and, unlike the first voyage, Cook selected them himself: HMS Resolution commanded by him, and HMS Adventure, commanded by Tobias Furneaux.[119] Resolution began her career as the North Sea collier Marquis of Granby, launched at Whitby in 1770. She was fitted out at Deptford with some of the most advanced equipment available, including an azimuth compass, ice anchors, and an apparatus for distilling fresh water from sea water.[120]

Banks planned to travel with Cook in the second voyage, but Banks' excessive demands for modifications to the ship conflicted with the Admiralty's constraints, so he withdrew from the voyage before it departed.[121] Banks was replaced by the German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster and his son, Georg Forster.[122] The crew also included the astronomer William Wales (responsible for the new K1 chronometer carried on Resolution), lieutenant Charles Clerke, and the artist William Hodges.[123]

Search for Terra Australis

After departing England, the ships travelled south to South Africa and stopped at Cape Town in November 1772.[125] From there they sailed eastwards, planning to circumnavigate the globe roughly between latitude 50°S and 70°S.[126][q] In late November 1772, the ships sighted their first icebergs and Cook performed an experiment: his crew retrieved blocks of ice and melted them on board the ships, producing good quality fresh water, proving that drinking water could be obtained from sea ice.[124] On 17 January 1773 the crews became the first recorded Europeans to cross the Antarctic Circle.[128] Despite his mission to find Terra Australis, Cook never sighted Antarctica in any of his voyages, but on 18 January – unbeknownst to him – the ships approached within 75 miles (121 km) of that continent.[124]

In February 1773, in dense Antarctic fog, Resolution and Adventure became separated.[129] Furneaux made his way – via Tasmania – to a pre-arranged rendezvous point to be used in the event of separation: Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand. Cook joined Furneaux there in May.[130] The crews traded with the Māori people, and in his journal, Cook expressed concern that crew members might be transmitting diseases to the Māori people and encouraging prostitution.[131]

Tahiti and New Zealand

The ships departed New Zealand in June – the southern winter – to resume their eastward search for Terra Australis.[133] About a month after leaving New Zealand, twenty crewmen aboard Adventure contracted scurvy – one of whom died – because Furneaux had failed to follow Cook's dietary instructions.[134] The ships proceeded in a small anti-clockwise loop, visiting Tahiti and Tonga, planning to return to New Zealand together.[135] Before reaching New Zealand, in the night of 29–30 October, the ships became separated for a second time – this time due to a storm.[136] Cook proceeded to the rendezvous point, and waited three weeks, then departed to continue the voyage alone.[137]

Delayed by storms, Furneaux arrived at the designated rendezvous point in Queen Charlotte Sound five weeks after they separated, missing Cook by four days.[137] In December 1773, while ten members of Adventure's crew were ashore gathering provisions, a violent altercation occurred with a group of Māori, resulting in the deaths of all the crewmen and two Māori.[138] Furneaux discovered the bodies of the crew members, partially burned in preparation for cannibalism.[139] Many members of Adventure's crew wanted to exact revenge on the Māori, but Furneaux thought it prudent to avoid additional violence, so they left New Zealand and returned to Britain without Cook.[140][r] When learning about the deaths much later,[s] Cook wondered if Furneaux's crew was at fault, writing "I must ... observe in favour of the New Zealanders that I have always found them of a brave, noble, open and benevolent disposition".[143]

Circuit around the South Pacific

After the missed rendezvous, Resolution made a large anti-clockwise loop in the south Pacific: heading far south, then visiting Easter Island, Tonga, and finally returning to New Zealand.[145] In the first stretch of this large loop, Resolution continued her search for Terra Australis by heading south-east, reaching her most southern latitude of 71°10′S in January 1774.[146] At this point, the ship's progress was blocked by impenetrable pack ice, and Cook wrote in his private diary: "I will not say it was impossible anywhere to get in among this Ice, but I will assert that the bare attempting of it would be a very dangerous enterprise and what I believe no man in my situation would have thought of. I whose ambition leads me not only farther than any other man has been before me, but as far as I think it possible for man to go..."[147]

In early 1774, Cook experienced a severe gastrointestinal illness, marked by prolonged abdominal pain and constipation. By February, his condition had worsened to the point where he became bedridden, causing considerable distress among the crew. The ship was out of fresh provisions and meat, so the Forsters offered their pet dog to be made into a soup, which Cook consumed. His bowel movements resumed in late February, but he remained weak for another month.[148]

In June 1774, the ship stopped to resupply at the island of Nomuka in Tonga, where most of the crew engaged in intimate relations with women. Cook was berated by an older woman after he declined – consistent with his usual conduct – to engage in sexual relations with a young woman who had been offered to him.[149] Cook was the first European to set foot on New Caledonia, in September 1774, and he claimed the land in the name of his king.[150] While there, Cook – despite warnings from Georg Forster – ate the liver of a poisonous pufferfish, and became numb and unable to walk without assistance; he recovered after taking emetics.[151]

When Cook completed the large anti-clockwise circuit and returned to Queen Charlotte Sound, the Māori welcomed his arrival. In conversations with them, Cook heard confusing stories about a conflict with the crew of a ship. Upon making inquiries, Cook learned that Adventure had visited the area approximately eleven months earlier, but he remained unaware of the violent encounter that had led to the deaths of ten of its crew.[152][s]

Return to England

Leaving New Zealand, Resolution proceeded home, sailing south of Tierra del Fuego, and stopping at South Georgia Island in January 1775, where Cook charted the coast and claimed the island group in the name of his king.[154] From there they continued eastward and discovered the South Sandwich Islands,[155] then stopped in South Africa, and – finally – sailed north back to Britain.[156]

Based on Cook's observations made during the second voyage, the general consensus was that Terra Australis did not exist. If the continent did exist, it should have extended into the temperate latitudes – yet Cook had demonstrated that no polar landmass reached beyond about 50°S.[157]

Cook was promoted to the rank of post-captain and given an honorary retirement from the Royal Navy, with a posting as an officer of the Greenwich Hospital.[158] He reluctantly accepted, insisting that he be allowed to quit the post if an opportunity for active duty should arise.[159] His fame extended beyond the Admiralty: he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society and awarded the Copley Gold Medal for a paper he wrote describing methods to prevent scurvy.[160] Nathaniel Dance-Holland painted his portrait; he was described as "the first navigator in Europe", and he met with noted author James Boswell.[16] Two books were published in 1777 about the expedition: one by Cook, and another by the Forsters.[161]

Remove ads

Third voyage (1776–1779)

Summarize

Perspective

The primary objective of Cook's third expedition was to search for a North-West Passage connecting the north Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic.[162] Simultaneously, the Admiralty was organising a second expedition – commanded by Richard Pickersgill, who had accompanied Cook on his first two voyages – to search for the North-West Passage from the Atlantic side.[163] To keep the goal of the mission secret, the Admiralty publicly declared that its aim was to return Polynesian native Mai to his home in Tahiti.[164][t]

On this voyage, Cook again commanded Resolution, while Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery.[166] Cook's lieutenants included John Gore and James King.[166] William Bligh was the master.[166] William Anderson was the surgeon (and also served as the voyage's botanist), William Bayly was the astronomer, and the official artist was John Webber.[166] Among the midshipmen was George Vancouver.[166] Welshman David Samwell served as the surgeon's mate.[167]

Tahiti and Hawaii

The third expedition began by sailing south from England, around South Africa into the Indian Ocean, where they stopped, in December 1776, at the desolate Kerguelen Island.[169] On the shore, the crew discovered a message in a bottle that had been left in 1774 by the French explorer Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen-Trémarec. Cook appended details of his own visit to the note, raised the British flag, and gave the island its current name.[169]

Continuing eastward to New Zealand, they anchored in February 1777 near the location where ten crew members of Adventure had been killed during the second voyage. Despite knowledge of the deaths, Cook treated the Māori with respect, even inviting them into his cabin. Some members of Cook's crew were confused and angered by their leader's failure to take revenge.[170]

The expedition then completed its first objective by returning Mai to his homeland of Tahiti.[171] While on Tahiti, Cook was allowed to observe a multi-day ritual involving a human sacrifice.[172] In October 1777, on the Tahitian island of Mo'orea, a goat belonging to the expedition was stolen by a local inhabitant. Cook organised a large search party and spent two days conducting an intensive search, destroying a large number of canoes and huts, until the goat was returned. Although several members of his crew considered the retaliation excessive, Cook did not record his reasoning for the destruction.[173]

They continued northward and – after a brief stop at Kiritimati – became the first recorded Europeans to see the Hawaiian Islands, on 18 January 1778.[174][u] During this first visit to Hawaii they made landfall at two locations: Waimea harbour on the island of Kauaʻi, and the nearby island of Niʻihau.[176] When he first stepped ashore, the Hawaiians prostrated themselves in front of Cook.[177] One of Cook's crew, John Williamson, shot and killed a Hawaiian man while ashore collecting provisions, infuriating Cook.[178] On Niʻihau, Cook left a pair of pigs for breeding, and pumpkin, melon, and onion seeds – continuing a practice he had followed on various islands throughout his voyages.[179] Cook observed remarkable similarities between the cultures of Hawaii and Tahiti, including language, marae structures, religion, and treatment of the dead.[180] He named the archipelago the "Sandwich Islands" after the fourth Earl of Sandwich – the First Lord of the Admiralty.[181]

North America

From Hawaii, Cook sailed north-east to reach the west coast of North America and begin his search for a North-West Passage.[183] He sighted the Oregon coast at approximately latitude 44°30′N, naming it Cape Foulweather, after the bad weather which forced his ships south to about 43°N before they could begin their exploration of the coast northward.[183] He unwittingly sailed past the Strait of Juan de Fuca and soon after entered Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island.[184] Cook's two ships remained in Nootka Sound from 29 March to 26 April 1778, in a cove at the south end of Bligh Island.[185] After leaving Nootka Sound, Cook explored and mapped the coast all the way to the Bering Strait, on the way identifying what came to be known as Cook Inlet in Alaska.[186]

By the second week of August 1778, Cook had sailed through the Bering Strait, crossed the Arctic Circle, and sailed into the Chukchi Sea.[187] He headed north-east up the coast of Alaska until he was blocked by sea ice at latitude 70°41′N.[188] Cook then sailed west to the Siberian coast, and then south-east down the Siberian coast back to the Bering Strait.[189] During this voyage, Cook charted the majority of the North American north-west coastline for the first time, determined the extent of Alaska, and closed the gap between earlier explorations of the north Pacific: Russian from the west, and Spanish from the south.[16] By early September 1778 he was back in the Bering Sea on his way to return to Hawaii.[190]

Cook became increasingly tired, harsh and volatile during his final voyage.[191] Tensions between Cook and his crew increased, his reprisals against crew members and indigenous people were more severe, and some officers began to question his judgement.[191][v]

Return to Hawaii

Cook returned to Hawaii in late November 1778, stopping first in Maui.[193] The ships sailed around the eastern portion of the archipelago for seven weeks, surveying and trading.[194] Cook made landfall at Kealakekua Bay on Hawaiʻi Island – the largest island in the archipelago – where the ships were met by 10,000 Hawaiians and 1,000 canoes.[195] On Hawaiʻi Island, Cook met with the Hawaiian king Kalaniʻōpuʻu, who treated Cook with respect, and invited him to participate in several ceremonies. The king and Cook exchanged gifts and names, and the king presented Cook with a feathered cloak.[196] Several members of the expedition speculated that Hawaiians thought Cook was a deity.[197] Later scholars confirmed the suspicions, and concluded that Hawaiians considered Cook to be the Polynesian god Lono.[198] Cook's arrival coincided with the Makahiki, a Hawaiian harvest festival of worship for Lono.[199] Some scholars believe that the form of HMS Resolution – specifically, the mast formation, sails and rigging – resembled certain significant artefacts that formed part of the season of worship.[200][w]

Death

After a month on Hawaiʻi Island, Cook set sail to resume his exploration of the northern Pacific, but shortly after departure a strong gale caused Resolution's foremast to break, so the ships returned to Kealakekua Bay for repairs.[203] Relations between the crew and the Hawaiians were already strained before the departure, and they grew worse when the ship returned for repairs.[204] Numerous quarrels broke out and petty thefts were common.[205] On 13 February 1779, a group of Hawaiians stole one of Cook's cutters.[206]

The following day, Cook attempted to recover the cutter by kidnapping and ransoming the king, Kalaniʻōpuʻu.[207] Cook and a small party marched through the village to retrieve the king.[208] Cook led Kalaniʻōpuʻu away; as they got to the boats, one of Kalaniʻōpuʻu's favourite wives, Kānekapōlei, and two chiefs approached the group. They pleaded with the king not to go and a large crowd began to form at the shore.[209] News reached the Hawaiians that a high-ranking Hawaiian chief had been shot (on the other side of the bay) while trying to break through a British blockade, which exacerbated the already tense situation.[210] Hawaiian warriors confronted the landing party and threatened them with stones, clubs, and daggers.[211] Cook fired a warning shot, then shot one of the Hawaiians dead.[212] The Hawaiians continued to attack and the British fired more shots before retreating to the boats.[213] Cook and four marines were killed in the affray and left on the shore.[214][x] Seventeen Hawaiians were killed.[216][y]

Aftermath

Hawaiians took the bodies of Cook and the marines inland to a village.[219] James King took a boat to the opposite side of the bay, and was approached by a priest who offered to intercede and ask for Cook's remains to be returned; King consented.[220] Some crewmen returned to the shore to collect water, and skirmishes broke out, resulting in the death of several Hawaiians.[221] On 19 February, a truce was arranged, and some of Cook's remains were returned to Resolution, including several bones, the skull, some charred flesh, and the hands with the skin still attached.[222] A large scar on the right hand – from his 1764 powder horn injury – confirmed that the remains belonged to Cook.[223] The crew placed the remains in a weighted box, and buried their captain at sea.[224]

Clerke had assumed leadership of the expedition[225] and the ships left the bay on 23 February 1779. They spent five weeks charting the coasts of the islands – in accordance with a plan set out by Cook before his death.[226] They travelled through the archipelago, stopping at Lanai, Molokai, Oahu, and Kauai.[226] On 1 April they departed the Hawaiian islands and sailed north to again try to locate the North-West Passage.[227] Clerke stopped in Kamchatka and entrusted Cook's journal, with a cover letter describing Cook's death, to the local military commander, Magnus von Behm.[228] Behm had the package delivered, overland, from Siberia to England.[229] The Admiralty, and all of England, learned of Cook's death when the package arrived in London – eleven months after he died. The package had arrived in England before the surviving crew.[230][z]

Continuing north, the expedition returned to the Bering Strait, but was again blocked by pack ice, and they were unable to discover a North-West Passage.[231] Clerke died of tuberculosis on 22 August 1779 and John Gore, a veteran of Cook's first voyage, took command of Resolution and the expedition. James King replaced Gore in command of Discovery.[232] The ships returned home, reaching England on 4 October 1780.[233]

Remove ads

Science, technology, and seamanship

Summarize

Perspective

Cook's seamanship and navigation skills enabled him to lead three expeditions which travelled tens of thousands of miles across mostly uncharted oceans and successfully gathered vast amounts of scientific and geographic knowledge, without the loss of a single ship.[235] His three voyages vastly expanded Europeans' knowledge of the Pacific Ocean, and revealed the existence of several lands and cultures previously unknown to Europeans, including the Hawaiian archipelago.[236]

Significant observations and discoveries were made by the scientists that Cook carried on each of his voyages: naturalists on the first voyage collected over 3,000 plant species;[237] and those on the second voyage published Observations Made During a Voyage Round the World, one of the first works which utilised a modern, interdisciplinary approach to geography.[238] Cook and Banks were among the first Europeans to interact with a wide variety of cultures in the Pacific. They identified similarities between peoples and languages across many Pacific Islands, leading them to suggest that the populations shared a common origin in Asia.[239]

Cook was an expert surveyor, cartographer, and hydrographer, and was well-versed in the use of instruments such as the theodolite, plane table, and sextant.[240] The charts of Newfoundland compiled by Cook were more accurate than new charts produced by the Royal Navy one hundred years later.[241] The charting skills he displayed in Newfoundland were a significant factor in his selection to lead the first Pacific voyage.[242]

Cook's naval career coincided with the advent of practical methods of determining longitude. On his first voyage, Cook took with him the 1768 and 1769 editions of the recently developed Nautical Almanac,[aa] which significantly reduced the time taken to calculate longitude from lunar distance observations.[243][ab] The data in the almanacs only reached a few years into the future, and each of Cook's voyages lasted longer than the data in the almanac – so the crew had to revert to using slower calculations near the end of the voyages.[244][ac]

On his second and third voyages, Cook carried Larcum Kendall's K1 chronometer – a copy of John Harrison's H4 – to test if it could accurately keep time for extended periods while withstanding the violent motions of a ship and the temperature changes of different climates. It performed well and thus made a key contribution to solving the longitude problem that had plagued mariners for centuries.[246] Cook praised the timepiece profusely.[247][ad]

Health and disease

Cook was among the pioneers in the early efforts to prevent scurvy, implementing various strategies including the provision of wort to the crew and the regular resupply of fresh food during voyages.[249] During his first circumnavigation of the globe he did not lose a single crew member to the disease – an uncommon outcome at the time.[250] In addition to diet, Cook also promoted general hygiene by having the crew wash themselves frequently and air out their bedding, clothes, and quarters.[251] He presented a paper on scurvy prevention to the Royal Society, and he was awarded their prestigious Copley Medal for contributions to medical and naval science.[252][ae]

Remove ads

Indigenous peoples

Summarize

Perspective

Conflict and cooperation

In his three Pacific voyages, Cook encountered numerous indigenous peoples, many with little or no previous contact with Europeans.[255] Cook's instructions from the Admiralty required him to cultivate friendships with indigenous peoples, treat them with civility, trade with them for provisions, and to report on the natural products of their lands and the "genius, temper, disposition and number" of the people.[256] Before the first voyage the Royal Society advised Cook that he should avoid violence against indigenous people, use lethal force only as a last resort, and – after tempers had calmed – explain to them that the British considered them the "Lords of the Country".[257] Upon initial contact with an indigenous people, Cook usually sought to establish amicable relations by engaging in local friendship rituals such as gift-giving, exchanging names,[258] presenting green boughs,[259] or hongi (rubbing noses).[260] He also relied on his Polynesian ship guests – Tupaia, Hitihiti, and Mai – to act as interpreters, advisers, and cultural intermediaries.[261]

The anthropologist Nicholas Thomas argues that despite Cook's peaceful intentions, violence was sometimes inevitable when indigenous people resisted contact by the British.[262] Following a violent encounter in 1774, Cook wrote, "we attempt to land in a peaceable manner, if this succeeds it's well, if not we land nevertheless and maintain the footing we thus got by the Superiority of our fire arms, in what other light can they than at first look upon us but as invaders of their Country".[263]

When conflict was likely, Cook implemented measures to minimise harm, such as instructing his crew to first fire warning shots, and to load their firearms with small shot, which was generally non-lethal. When Cook was not present, his crew sometimes disobeyed his orders and changed their weapons to use more fatal musket balls.[264]

The level of violence fluctuated throughout the three voyages. Many encounters were almost entirely peaceful while in other cases generally friendly relations were punctuated by sporadic violence.[265] Overall, at least 45 indigenous people were killed by Cook's crew, including two killed by Cook.[af] Fifteen of the crew were killed by indigenous people, including Cook himself.[ag] The worst incidents of deadly violence occurred in New Zealand during the first and second voyages, and in Hawaii during the third voyage.[271]

The British often resorted to violence when they felt threatened or believed that indigenous people were engaging in theft or dishonest trade.[272][ah] Cook generally overlooked minor thefts, but punished thefts of official property – especially essential equipment – more severely.[274] To avoid excessive bloodshed he usually responded to thefts with warning shots, floggings, the seizure of canoes, or by holding indigenous leaders hostage until the stolen items were returned.[275]

Cook was criticised by various crew members for being too lenient in his punishment of indigenous people for violence, theft, and defiance.[277] Local indigenous people and Cook's Polynesian advisers sometimes encouraged him to impose more severe punishments on other indigenous groups or commoners.[278]

These advisers were dismayed when – during the third voyage – he refused to punish the Māori group that killed ten crew members of Adventure.[279][ai] Cook's handling of the incident also caused resentment among crew members.[280] Subsequently he increasingly resorted to harsher non-lethal punishments against indigenous people – which some crew members considered excessive.[281] These measures included the destruction of canoes and dwellings,[282] extreme floggings,[283] and cropping their ears.[284]

Cook's ceremonial friendships with Polynesian high chiefs sometimes caused tensions. While they brought Cook prestige among the local population and a place in their culture, they involved cultural obligations – such as generous gift-giving, defending local customs, avenging insults, and acting as an ally against the chief's enemies – which Cook did not always fully understand and which embroiled him in internal politics.[285] Cook's need to gather supplies of food, water and timber during his stays caused tension with the local population when he arrived during seasonal scarcity, or in areas ravaged by wars, or when chiefs withheld supplies for political reasons.[286]

Cook and his crew caused offence when they inadvertently or deliberately violated customs involving rituals, shrines, high chiefs, and sacred wildlife.[287] Cook's actions in taking high chiefs hostage for the return of stolen goods caused particular offence and almost resulted in violence in Tonga and Tahiti before the deadly violence in Hawaii.[288]

Cook as chief or deity

Cook was considered by some indigenous peoples to be an ariki (high chief), and therefore the embodiment of the powers and attributes of certain atua (Polynesian gods).[289][aj] Cook's status as an ariki in much of Polynesia was due to his leadership role when making contact with indigenous people, the deference crew members displayed towards him, the power of the weapons he commanded, and the respect he gained by becoming ceremonial friends with local chiefs.[292] Ceremonial friendships typically involved Cook and a chief exchanging genealogies, names, and symbols of their status (for example, uniforms and weapons), by which their ancestries and mana (life force) would be merged.[293] In Hawaii, Cook's status as an akua (the Hawaiian version of atua) derived partly from the time and manner of his arrival during his second visit in late 1778. Many Hawaiians thought Cook was an embodiment of the Polynesian god Lono.[294]

Trading and commerce

Cook's orders instructed him to barter with indigenous peoples to replenish his ship's provisions.[296] When bartering, Cook primarily received food from the indigenous peoples, including fish, pigs, plantains, bananas, coconuts, and breadfruit.[297] In return Cook gave items such as iron nails, beads, copper, knives, and cloth.[298] The crew also bartered individually with indigenous peoples, often to purchase "curiosities", hatchets, and other souvenirs, and also for sex.[299]

Cook carried a wide variety of livestock on his ships including pigs, goats, cattle, horses, rabbits, turkeys, and sheep.[300] The ships also carried cats and dogs as pets.[301] The livestock were used for a variety of purposes: for consumption by the crew, to place onto lands they visited to establish breeding pairs, and to give to indigenous individuals as gifts.[300]

Cook also brought plants and seeds on his ships, and planted gardens on several islands. The plants included wheat, carrots, peas, mustard, cabbages, strawberry, parsley, potatoes, oranges, lemons, pomelo, limes, watermelons, turnips, onions, beans, and parsnip.[302] The crops were intended for the benefit of the indigenous peoples, and also to feed future British visitors.[303] The crew also planted pineapple and grape (from vines planted earlier by Spaniards) that were obtained from Pacific islands.[304]

Cross-cultural exchanges

Cook's expeditions resulted in considerable cultural exchanges with the indigenous peoples of the Pacific region. Several members of his crew learnt to speak Polynesian languages, and Polynesian words such as tabu (taboo)[305] and tatu (tattoo) entered the English language.[306] Crew members called Cook's fits of anger "heivas" (the Tahitian word for a public performance), and they called Cook "Toote" (the Tahitian transliteration of his name).[307] Many Polynesians also learnt some English, Tupaia and Mai becoming fairly proficient.[308] "Cookees" became a Tahitian word for Europeans.[309]

Polynesians adopted some European foods and Cook's crew also developed a taste for local foods. Dog was a common food in Polynesia and Cook's crew came to eat it with enjoyment.[310] The Māori enjoyed the ship's salted meat and Mai tried to produce wine on his island.[311] Cook brought European livestock and crops to the Pacific and brought exotic plants back to England.[312]

Cook's crew embraced the practice of tattooing, which later became a tradition among sailors worldwide.[313] Tahitians extended the meaning of their word tatau to include European writing.[314] Polynesians admired the work of the crew's artists and Tupaia learnt to draw and paint in the English style.[315] Tahitians, Tongans and Hawaiians staged boxing and wrestling matches in which crew members sometimes participated, and they often exchanged musical performances and dancing.[316]

Several Polynesians joined Cook's expeditions as ship guests. Tupaia advised Banks on Polynesian culture and explained Polynesian navigational methods to Cook, helping him make a chart of South Pacific islands.[317] Mai, in his two years in England, became a celebrity and an unofficial cultural ambassador for his homeland. On his return to the Tahitian islands he attempted to spread knowledge of England.[318][t]

Cook and his officers attended Polynesian ceremonies and sacred rituals while Polynesians, in turn, occasionally observed and participated in the British religious services and burials.[319] When one crew member died in Hawaii the Hawaiian priests agreed that he should be buried in their local shrine and they turned the funeral into as cross-cultural ritual.[320] After Cook's death, his memory and physical remains were incorporated into Hawaiian rituals for decades.[321]

Many Polynesians became friends or lovers with their visitors, and some crew members attempted desertion to be with their Polynesian lovers.[322] Cook entered into ceremonial friendships with Polynesian chiefs for practical reasons but also developed emotional attachments to some of them.[323]

European knowledge of the indigenous cultures of the Pacific region increased with the publication of accounts of the voyages. These accounts were popular but spread some misconceptions about indigenous peoples.[324][ak] The art of the voyages also proved popular, many works being reproduced in cheap editions and as book illustrations.[327] The artists strove for scientific accuracy but sometimes distorted actual events and fostered a particularly European vision of the Pacific and its cultures.[328]

Health and sexual relations

Many European explorers – including members of Cook's crews – carried communicable diseases such as syphilis, gonorrhea, tuberculosis, malaria, dysentery, smallpox, influenza, and hepatitis.[330] These diseases caused a significant decline in some local populations, who often had no natural resistance.[331] Cook's crews transmitted some of these diseases to indigenous peoples in Tahiti, Hawaii, British Columbia, and New Zealand.[332] In Hawaii, Cook's crews were the first Europeans to introduce some diseases to the local population.[333][al]

Sexual mores differed greatly between Britain and the places visited by Cook. Of Hawaii, the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins writes: "We can see why Hawaiians are so interested in sex. Sex was everything: rank, power, wealth, land, and the security of all these."[335] Most sexual encounters were consensual, but they often involved payment in the form of trinkets, feathers, or iron nails.[336] In Hawaii, some women believed that sex with white men would increase their mana (spiritual power).[337] In New Zealand during the second voyage, Māori men forced women to have sex with the crewmen.[338]

Cook took measures to mitigate the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including issuing orders that prohibited women from boarding his ships and instructing his crew to refrain from sexual relations with indigenous women.[333] In Hawaii he specifically ordered that "no woman was to board either of the ships" and that any crew member known to have an STD was forbidden from engaging in sexual activity, stating these directives were intended "to prevent as much as possible the communicating [of] this fatal disease to a set of innocent people". However, Cook's orders were frequently disregarded by members of his crew.[339]

Cook's observations

Cook's instructions required him to report on the indigenous peoples he encountered.[341] Over time he developed an interest in their cultures and his observations became more sophisticated as he attempted to understand cultural differences and describe them in a detached manner.[342]

Cook described the Māori as brave, noble, open, benevolent, devoid of treachery, and having few vices.[343] He believed that Aboriginal Australians were happier than Europeans because they enjoyed social equality in a warm climate and were provided with all the necessities of life, and therefore had no need of trade with Britain[344] (see the manuscript page). While such views partly reflected Enlightenment ideas of the noble savage living in a state of nature, they were contrary to the popular notion in Britain and among Cook's crew members that indigenous people were savages living in societies inferior to British civilisation.[345]

Cook sometimes questioned the idea that contact with Europeans would benefit indigenous people. In 1773 he wrote: "we debauch their Morals already too prone to vice and we introduce among them wants and perhaps diseases which they never before knew and which serves only to disturb that happy tranquility they and their fore Fathers had enjoyed. If any one denies the truth of this assertion let him tell me what the Natives of the whole extent of America have gained by the commerce they have had with Europeans."[346]

Whereas his crew saw the cannibalism of the Māori as a sign of their savagery, Cook viewed it as merely a custom that they would discard when they became more united and less prone to internal wars.[347] He reported that the Polynesian peoples shared a common ancestry, a tradition of long sea voyages, and had developed into different nations over time. According to Thomas, his comments reflect a more historical and less idealised approach to understanding indigenous cultures than was common in this period.[348]

Cook sought to refute misconceptions about indigenous peoples. His comments on Aboriginal Australians were a rebuttal of William Dampier's disparaging account.[349] He corrected Bougainville's implication that all property on Tahiti was communally owned, noting that fruit trees belonged to individuals.[350] He countered the British belief in the promiscuity of Tahitian women, arguing that while they had a different attitude to sex, married women and many unmarried women did not provide sex for gifts.[351] Nevertheless, Cook himself sometimes used derogatory terms for indigenous people and made adverse judgements without observing their cultures closely and questioning them on their practices and beliefs.[352]

Remove ads

Personal life and character

Summarize

Perspective

On 21 December 1762, Cook married Elizabeth Batts at St Margaret's Church, Barking, Essex. She was the daughter of Samuel Batts, keeper of the Bell Inn in Wapping and one of Cook's mentors.[354] When not at sea, Cook lived in the East End of London and attended St Paul's Church, Shadwell.[355]

The couple had six children.[356] Four were born before the first voyage: James (1763–1794), Nathaniel (1764–1780), Elizabeth (1767–1771), and Joseph (1768–1768). George (1772–1772) was born before the second voyage, and Hugh (1776–1793) was born before the third voyage. Cook has no direct descendants – all of his children died before having children of their own.[357][am]

Six years after Cook's death, his widow petitioned for a coat of arms to preserve the memory of her late husband and to be placed on monuments and memorials.[353] The coat of arms was granted in September 1785 and is the only known example of a posthumously granted coat of arms.[358]

The historian John Beaglehole characterises Cook as profoundly competent, a man of action, obedient, patient, persistent, ambitious (but not overly so), and hot tempered when confronted with incompetence or disobedience. Cook did not often confide in fellow officers about his private thoughts or plans; nor did he make major decisions by consensus. Cook was not religious, mystical, romantic, or dramatic.[359] The anthropologist Anne Salmond, based on the journals of Heinrich Zimmermann, describes Cook as chaste with regard to women, strict, and frugal. He did not swear or get drunk, and did not tolerate priests aboard his ships. He was fearless and calm in times of danger.[360] Nicholas Thomas writes that Cook could demonstrate self-denial when needed, and he practised celibacy on voyages. He could sense the mood of his crew, but he could also be obstinate, even when flexibility was called for.[361]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Commemorations

Important monuments to Cook include one in the church of St Andrew the Great in Cambridge, where his wife and two of his sons are buried,[363] and statues of Cook in Hyde Park in Sydney, and at St Kilda in Melbourne.[364]

The Royal Research Ship RRS James Cook was built in 2006, and serves in the UK's Royal Research Fleet.[365] NASA named several spacecraft after Cook's ships.[366] Cook has appeared on many stamps and coins: Over four hundred stamps have been issued in his honour,[367] and dozens of coins have been issued with Cook's image.[368] Many institutions are named after him, including James Cook University in Townsville, Australia,[369] and James Cook University Hospital, in Middlesbrough, England.[370]

Since 1959, an annual reenactment of Cook's 1770 landing has been held near the site of the original event in Cooktown, with the support and participation of many of the local Guugu Yimithirr people.[371] The reenactments celebrate an act of reconciliation when a local elder presented Cook with a broken-tipped spear as a peace offering, after a conflict over sharing green turtles which Cook's men had taken in violation of local custom.[372]

In the years surrounding the 250th anniversary of Cook's first voyage of exploration, various memorials to Cook in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Hawaii were vandalised,[373] and there were public calls for their removal or modification due to their perceived association with British colonialism.[374]

Ethnographic collections

The largest collection of artefacts from Cook's voyages is the Cook-Forster Collection held at the University of Göttingen in Germany.[375] The Australian Museum in Sydney holds over 250 objects associated with Cook's voyages. The objects are mostly from Polynesia, although there are also artefacts from the Solomon Islands, North America and South America.[376]

Indigenous people have campaigned for the return of indigenous artefacts taken during Cook's voyages.[377] The art historian Alice Proctor argues that the controversies over public representations of Cook and the display of indigenous artefacts from his voyages are part of a broader debate over resistance to colonialist narratives and the decolonisation of museums and public spaces.[378]

Reputation and influence

When news of Cook's death reached Britain and continental Europe, obituaries, poems and tributes emphasised his humble birth, technical skills, leadership qualities, contributions to science and trade, and his concern for the well-being of his crew and indigenous people.[379] William Cowper and Goethe wrote tributes, and there were many theatrical and artistic representations of his death.[380]

One of the earliest monuments to Cook in the United Kingdom was erected in 1780 at The Vache by Hugh Palliser, a friend of Cook.[381] In 1780 Joseph Banks, now president of the Royal Society, publicised Cook's legacy, and he had the society mint a commemorative medal.[382] Praise for Cook was almost universal in England, although Alexander Dalrymple (a rival of Cook for leadership of the first voyage) remarked on the adulation of Cook: "I cannot admit of a Pope in Geography or Navigation".[383] There were no notable commemorations in England to mark the centenary of Cook’s death in 1879.[384][an]

Banks used the fame surrounding Cook's voyages to help promote a new colony in Australia, and in 1788 the First Fleet arrived in what is now Sydney.[385][386] After Britain established colonies in Australia and New Zealand, the colonists began to consider Cook as a founding father.[387] In 1822, the Philosophical Society of Australia placed a monument at Cook’s supposed landing place in Botany Bay.[388][ao] The treatment, with overtly heroic overtones, of Cook as a founder continued in the early 1900s when the Commonwealth of Australia was established.[389]

European visitors to Hawaii in the decades following Cook's death found many Hawaiians carrying fond memories of Cook.[390] In the 1830s American missionaries in Hawaii discovered that Cook had been worshiped as a kind of deity, and embarked on a campaign to disparage his memory. An early written history of Hawaii was derived from Hawaiian oral histories by missionary Sheldon Dibble. It portrayed Cook as an idolator and spreader of STDs, and greatly influenced native Hawaiian historians.[391][392]

The bicentennial of Cook's voyages in the 1970s brought a resurgence of interest and numerous commemorations.[393] In the late 20th century increasing attention was given to the perspectives of Indigenous peoples and public discourse began to acknowledge the detrimental impacts of European contact on Indigenous communities.[394]

In the 21st century Cook is widely regarded as one of the greatest sea explorers.[395] His voyages greatly expanded geographical knowledge and paved the way for later British engagement in the Pacific.[235] But for many people – particularly indigenous people of the lands he visited – he is a symbol of the adverse consequences of European contact and colonisation.[396] Critics, such as the Native Hawaiian scholar Haunani-Kay Trask, highlight violent encounters, the spread of infectious diseases, and the claiming of indigenous lands without consent.[396][ap] The scholars Robert Tombs, Nicholas Thomas, and Glyndwr Williams – while acknowledging the negative impacts of the expeditions – contend that Cook should not be held responsible for the consequences of colonialist policies that were initiated after his death.[399]

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads