Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Second voyage of James Cook

1772–75 British maritime voyage From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

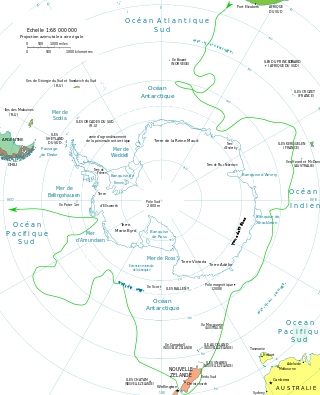

The second voyage of James Cook, from 1772 to 1775, commissioned by the British government with advice from the Royal Society, was designed to circumnavigate the globe as far south as possible to finally determine whether there was any great southern landmass, or Terra Australis. On his first voyage, Cook had demonstrated by circumnavigating New Zealand that it was not attached to a larger landmass to the south, and he charted almost the entire eastern coastline of mainland Australia, yet Terra Australis was believed to lie further south. Alexander Dalrymple and others of the Royal Society still believed that this massive southern continent should exist. After a delay brought about by the botanist Joseph Banks' ship modification requests, the ships Resolution and Adventure were fitted for the voyage and set sail for the Antarctic in July 1772.

On 17 January 1773, Resolution was the first ship to venture south of the Antarctic Circle, which she did twice more on this voyage. The final such crossing, on 3 February 1774, was to be the most southerly penetration, reaching latitude 71°10′ South at longitude 106°54′ West. Cook undertook a series of vast sweeps across the Pacific, finally proving there was no Terra Australis in temperate latitudes by sailing over most of its predicted locations.

In the course of the voyage he visited Easter Island, the Marquesas, Tahiti, the Society Islands, Niue, the Tonga Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, Palmerston Island, South Sandwich Islands, and South Georgia, many of which he named in the process. Cook proved the Terra Australis Incognita to be a myth and predicted that an Antarctic land would be found beyond the ice barrier. On this voyage the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer was successfully employed by William Wales to calculate longitude. Wales compiled a log book of the voyage, recording locations and conditions and the use and testing of various instruments, as well as making many observations of the people and places encountered on the voyage.

Remove ads

Conception

Summarize

Perspective

Upon the return of the Endeavour, after James Cooks first voyage the English public had showed intense curiosity about the findings from the Pacific. The success of Cook’s first journey surpassed all earlier expeditions and brought back useful knowledge, as well as a proposal to resolve the question of a southern continent once and for all. The widespread attention and ongoing questions about geography and natural history helped ensure official support for another Pacific expedition. Thus the Admiralty quickly began preparing for another expedition, seeking an appropriate ship and planning the next steps.[1]

Cook had a more significant role in organizing his new expedition, than in 1768. The Navy Board consulted him on ship purchases and decided to acquire two vessels designed for the North Sea coal trade, named the Drake and the Raleigh, based on Cook's recommendation for an escort after previous experiences. The ships, weighing 450 tons and 336 tons respectively, were later renamed the Resolution and the Adventure to avoid diplomatic tensions with Spain at the suggestion of the Lord of the Admiralty. Additionally, Cook had more control over the choice of his crew this time, and he witnessed the rehire of a number of Endeavour crew members, most notably Richard Pickersgill as third lieutenant and Charles Clerke as second lieutenant of the Resolution. Thirteen sailors, six of whom had been promoted to petty officer grade, and three midshipmen, Isaac Smith, William Harvey, and Isaac Manley, had returned. Second Lieutenant John Edgcumbe, the senior marine, was an Endeavour veteran; oddly, Samuel Gibson, a former Tahiti deserter who was now promoted to corporal, was the other returning marine. Cook chose Joseph Gilbert, who had collaborated with him on the Newfoundland survey, to be the master of the Resolution.[2]

Cook had little trouble selecting the remaining members of his crew. Following the Endeavour's journey, young men used whatever influence they could summon to demand berths alongside Cook. Robert Palliser Cooper, the first officer of the Resolution, was related to Sir Hugh Palliser, the navy comptroller and one of Cook's early backers. John Elliott, a thirteen-year-old midshipman, was also sent to the Resolution. James Burney, a twenty-one-year-old able seaman and eleven-year Navy veteran, was the son of Lord Sandwich's acquaintance and well-known musician and musical historian Charles Burney. Burney was "clever & excentric," according to Elliott. After a lengthy and successful naval career, Burney wrote a five-volume history of Pacific exploration. George Vancouver, a fourteen-year-old who Elliott characterized as a "quiet inoffensive young man," was one of the other able seamen. The Resolution was his first Navy assignment. With the exception of its captain, Tobias Furneaux, the capable and popular second lieutenant of the Dolphin under Samuel Wallis, the Adventure's crew was unfamiliar with Pacific expedition.[3]

Cook was asked to test the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer on this voyage. The Board of Longitude had asked Kendall to copy and develop John Harrison's fourth model of a clock (H4) useful for navigation at sea. The first model finished by Kendall in 1769 was an accurate copy of H4, cost £450, and is known today as K1. Although constructed like a watch, the chronometer had a diameter of 13 cm and weighed 1.45 kg. Three other clocks, constructed by John Arnold were carried but did not withstand the rigours of the journey.[4] The performance of the clocks was recorded in the logbooks of astronomers William Wales and William Bayly, and as early as 1772 Wales had noted that the watch by Kendall was 'infinitely more to be depended on'.[5]

Provisions loaded onto the vessels for the voyage included 59,531 pounds (27 t) of biscuit, 7,637 four-lb (approx 1.8 kg) pieces of salt beef, 14,214 two-lb (approx 1 kg) pieces of salt pork, 19 tuns (about 18,000 litres) of beer, 1,397 imperial gallons (6,350 L) of spirits 1,900 pounds (860 kg) of suet and 210 imp gal (950 L; 250 US gal) of 'Oyle Olive'. As anti-scorbutics they took nearly 20,000 pounds (9.1 t) of 'Sour Krout' and 30 imperial gallons (140 L) of 'Mermalade of Carrots'.[a] Both ships carried livestock, including bullocks, sheep, goats (for milk), hogs and poultry (including geese). The crews had fishing gear (supplied by Onesimus Ustonson)[6] and a water purification system designed by Charles Irving was carried for distilling sea-water or purifying foul fresh-water. Various pieces of hardware (such as knives and axes) and trinkets (beads, ribbons, medallions) to be used for barter or as gifts for the natives were also taken aboard.[4]

It was originally planned that the naturalist Joseph Banks and what he considered to be an appropriate entourage would sail with Cook, so a heightened waist, an additional upper deck and a raised poop deck were built on Resolution to suit Banks. However, in sea trials the ship was found to be top-heavy, and under Admiralty instructions the offending structures were removed in a second refit at Sheerness. Banks subsequently refused to travel under the resulting "adverse conditions".[7] Instead the position was taken by Johann Reinhold Forster and his son, Georg, who were taken on as Royal Society scientists for the voyage. Resolution carried a crew of 112; as senior lieutenants Robert Cooper and Charles Clerke and among the midshipmen George Vancouver and James Burney. The master was Joseph Gilbert and Isaac Smith, a relation of Cook's wife was also aboard. William Wales was the astronomer and William Hodges the artist. In all, there were 90 seamen and 18 royal marines as well as the supernumeraries.[8]

Remove ads

Voyage

Summarize

Perspective

Cook's second voyage of discovery departed Plymouth Sound on Monday 13 July 1772. His first port of call was at Funchal in the Madeira Islands, which he reached on 1 August. Cook gave high praise to his ship's sailing qualities in a report to the Admiralty from Funchal Roads, writing that she "steers, works, sails well and is remarkably stiff and seems to promise to be a dry and very easy ship in the sea".[9] After a short stay, Cook sailed for Porto Praya, San Tiago (Cape Verde Islands), arriving at 12 August. He collected water and enforced strict routines aboard the Resolution, such as pumping out the bilge with seawater, airing and drying bedding, washing clothes, and brewing Pelham’s experimental beer. Furneaux did not require similar practices on the Adventure. The ships were compared for sailing ability, with the Resolution initially performing better, but later trials offered no clear advantage.[10]

At Porto Praya, the water quality was acceptable, though not good. Livestock like bullocks could not be obtained, but hogs, goats, poultry, and fruit were plentiful. The Forsters collected botanical specimens, Cook and Wales surveyed the bay, and sailors purchased monkeys, which were soon thrown overboard due to the mess they caused. Five days after leaving Porto Praya, Henry Smock, a carpenter’s mate, drowned while working over the side of the ship. About a week later, Cook learned from Furneaux that an Adventure midshipman had died, followed by another less than three weeks later, both apparently from fever. Dr James’s Powders and Dr Norris’s Drops were ineffective. Some ill crewmen recovered, but the early sickness raised questions, especially since the Resolution had no cases of illness, even after tropical rains.[10]

On September 8, the ships crossed the equator. The Resolution crew held celebratory events, but none took place on the Adventure for safety reasons. Cook continued with experiments, such as testing sea currents, measuring water temperature at depths with a thermometer, and comparing methods to obtain fresh water. Collecting rainwater worked better than distillation. Some sailors were skeptical of the experimental beer, preferring water. On October 30, both ships anchored in Table Bay near Capetown. Officers noted the continued good health of the Resolution’s crew, which they credited to Cook’s strict cleanliness measures. The Adventure’s crew was also generally well, apart from Lieutenant Shank’s ongoing gout. In contrast, two newly arrived Dutch Indiamen had lost about two hundred men to scurvy.[11]

Cook found the Cape a satisfactory port of call, though delays were common, particularly with baking bread and preparing spirits. The acting governor, Baron van Plettenburg, and merchant Mr Brand were helpful. The crew enjoyed fresh food and shore leave. Wales and Bayly conducted astronomical observations and checked chronometers. The Kendall chronometer on the Resolution was working well, but the Arnold instrument had problems after being jarred, and another on the Adventure stopped completely. While at the Cape, Cook heard vague reports of French voyages: Kerguelen’s 1772 expedition to the south, and Marion du Fresne’s mission to Tahiti, though he did not learn the commanders’ names. He also learned that the Tahitian Ahutoru had died of smallpox. There were some changes among the officers. Lieutenant Shank of the Adventure left due to illness, replaced by Arthur Kempe, and James Burney was promoted to second lieutenant. Forster met Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman, who joined the expedition as an assistant naturalist at his own expense. Cook spent the remaining time at the Cape (late October) writing letters and reporting on the experimental beer and other matters to the Admiralty.[12]

The ships left the Cape on 22 November 1772 and headed for the area of the South Atlantic where the French navigator Bouvet claimed to have spotted land that he named Cape Circoncision. Cook was three weeks behind schedule, but this delay likely allowed the Antarctic pack ice more time to break up, enabling him to sail farther south. He was inexperienced with Antarctic ice navigation, as were most of his crew, and had to discard common beliefs, such as the idea that ice always indicated nearby land. The expedition also learned that the prevailing winds beyond 60° S were easterly, differing from earlier assumptions.[13]

Antarctic Circle

Shortly after leaving they experienced severe cold weather and Cook distributed warm fearnought clothing to each man as they sailed south into increasingly harsh conditions.[14] By December 10, at nearly latitude 51°, they sighted their first large iceberg and soon encountered many more. On December 13, Cook recorded being in latitude 54°, about 118 leagues east of Bouvet’s cape, before being stopped by the pack ice at 54°55’ S. He noted whales, penguins, and other wildlife, and found that ice from the pack produced fresh water. On December 14, the ships turned SSW, seeking open water, but soon were forced north and east again to avoid being trapped by ice. Thick fog and snow made navigation difficult, and on December 17, Cook was again halted by heavy pack ice. By December 18, the ships had sailed about ninety miles east along the ice edge. Cook speculated that land might exist behind the ice but could not confirm it, so he decided to run 30–40 leagues east before again trying to head south.[15]

As the crew encountered some signs of scurvy, they used wort from malt to treat the affected. Christmas Day, December 25, was celebrated with rum and festivities, despite the harsh surroundings. By December 27, the ships were 240 miles south of their position a week earlier, likely having navigated around a tongue of pack ice stretching east from the Weddell Sea. Cook decided to proceed west towards the meridian of Cape Circumcision. On December 29, Cook attempted to collect ice for water, and on January 3, 1773, he determined, in latitude 59°18’ S and longitude 11°9’ E, that Bouvet’s Cape Circumcision did not exist as land, but was likely only mountains of ice. He concluded that if there was land, it could only be a small island, and he saw no reason to continue searching in that direction. Instead, he planned to head east in search of the land reported by the French at about latitude 48° S, longitude 57–58° E.[16]

On January 4, 1773, the ships were running east, and Cook inferred that the large ice field they had encountered days earlier had drifted northward. On January 9, the crew successfully harvested ice for fresh water, providing more and better water than they had left Cape Town with. Cook continued scientific experiments, such as measuring sea temperatures at depth and questioning prevailing theories about ice and salinity. Cook then steered south, and on January 17, 1773, just before noon, he became the first to cross the Antarctic Circle, at latitude 66°36.4’ S and longitude 39°35’ E.[17][18][19] Realizing that he could not get further south Cook wrote: From the masthead I could see nothing to the Southward but Ice… [b] Cook then decided to search for the Kerguelen islands, which had been discovered in 1771 by Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen-Trémarec. After seven days unable to locate the islands Cook called off the search.[21] He hoped for open sea, but soon encountered more pack ice and was forced to tack and change course at latitude 67°15’ S. For the rest of January, Cook sailed northeast, spreading the ships apart to maximize their view. The weather remained harsh, and the search for the reported French land continued into February. Furneaux observed signs that seemed to indicate nearby land, but with the prevailing winds, Cook could only proceed east. On February 6, realizing the evidence did not support the presence of land to the west, he continued east and south. Despite detailed searching, they found no trace of the supposed land, as Clerke noted in his journal.[22]

New Zealand

On 8 February, thick fog caused the ships Resolution and Adventure to become separated. Their agreed method for keeping contact was to fire guns at intervals, signaling each other whenever they changed course. On this occasion, however, the Resolution’s signals went unanswered. Although some sailors thought they could hear distant replies, others believed the sounds came from cracking icebergs. Cook searched the area for two days, but with no sign of Adventure, he was forced to give up and follow the contingency plan: the ships would attempt to rendezvous at Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand. The separation hindered Cook’s search for Kerguelen’s land. Ultimately, he sailed too far south to sight it. The island did exist, but though it had fresh water, it was sparse and difficult to access—Cook would have faced the same landing problems as Kerguelen.[23]

After losing the Adventure, morale on the Resolution was low. Stores were running short, food was repetitive, and many men suffered from colds and other ailments. The elder Forster was particularly irritable, worsening the general mood. Petty theft broke out and Cook resorted to flogging as punishment. The sailors’ fearnought jackets were ragged after twelve weeks at sea, so Cook issued materials for repairs. Despite the hardships, Cook persisted with his mission, aiming to cross the Antarctic Circle a second time. Though he could have become the first to chart southern Australia, he decided it was safer and more prudent to head for New Zealand, where he could resupply and regroup.[23]

The Resolution had been at sea for over three months, braving the icy southern oceans through February and into March. The cold was so intense that animals had to be taken below deck to survive, causing cramped and unpleasant conditions, especially for Forster, who wrote about the discomfort of sharing his cabin space with livestock and enduring constant cold and damp. He tried to maintain his composure, but privately confessed he would not repeat such a voyage for twice the money, preferring steady work in England. The journey, he lamented, yielded little of interest for a naturalist: no new land, no plants brought by icebergs, only seabirds and penguins. Still, the crew’s health remained good, with no cases of scurvy despite fifteen weeks in the harsh Antarctic climate. For another month, the Resolution sailed along the ice edge near the 60th parallel, then finally turned north for New Zealand. The passage from Cape Town had crossed 157 degrees of longitude—a remarkable feat, even though no land had been found in the Antarctic. On 26 March 1773, New Zealand’s westernmost cape was sighted. The coast was dangerous, but Cook knew it was vital to land soon and allow his exhausted crew to recuperate.[24][25]

On the Adventure, conditions were similar. The ship heard Resolution’s distant gun, fired a reply, and continued attempting contact every half hour through the fog, but no reunion occurred. When the fog lifted briefly, they thought they glimpsed the Resolution but could not catch her. After another day searching in vain, Captain Furneaux also followed the plan to meet in Queen Charlotte Sound. Navigation was aided by a reliable Arnold watch and astronomer Bayly. Furneaux chose a course at about 52° S, a more temperate latitude than Cook’s, and began searching for Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), discovered by Tasman in 1642.By late February, the Adventure encountered fewer icebergs. The skies were clear, and the crew witnessed a bright meteor and, for several nights, a spectacular display of the southern lights (aurora australis). Astronomer William Bayly was especially impressed, noting that the lights were so bright he could read by them. George Forster on the Resolution described the aurora as columns of white light stretching almost to the zenith, differing from the coloured northern lights.[26]

On 1 March, a false sighting of land—actually a cloud—reflected the strain of the voyage. The isolation affected morale, and one midshipman, George Moorey, imagined seeing his father’s ghost during a lonely watch. But on 9 March, genuine land was spotted: the Adventure had reached Van Diemen’s Land. Furneaux struggled to reconcile his observations with Tasman’s charts because of the many offshore islands. He sought a safe anchorage, and on the second attempt, after rough seas and missed signals, Burney’s party landed at what became Louisa Bay. The landing provided fresh water and a safe spot, though it was not the bay Tasman had described. Furneaux named it Adventure Bay, likely Tasman’s Storm Bay. The crew made some discoveries of local animals and plants, including possums, Tasmanian stinging ants, and gum trees.[27]

On 15 March, the Adventure sailed north, mapping Tasmania’s east coast. St Patrick’s Head and St Helen’s Point were named as the ship proceeded. Strong swells soon drove the ship out to sea, but Furneaux observed more islands to the north (now Barren and Flinders Islands), correctly guessing they were separate from the mainland. However, he incorrectly concluded that Van Diemen’s Land and New Holland (Australia) were connected, missing the opportunity to confirm the existence of Bass Strait. On 19 March, the Adventure left Tasmania and set course for New Zealand, arriving at Ship Cove on 7 April.[28][29]

When the Adventure arrived at the meeting point, the Resolution was already anchored elsewhere in New Zealand. Cook risked entering Dusky Sound on the South Island to find shelter and resources after a long and difficult voyage. The area provided fresh water, wood, and greenery, which helped restore the crew and ship. Only a few animals survived the journey, and some suffered from scurvy. Cook and his officers explored the region to find the best anchorage, and the crew took advantage of the abundant fish and wildlife. The landscape impressed the naturalists, who noted the dense forests and numerous waterfalls. The local Maoris were cautious but curious, and Cook made efforts to build trust through gestures and gifts. Some interaction followed, with music and conversation on the Resolution, although both groups remained wary of each other. The crew set up temporary facilities, including an observatory and workshops, while carrying out small expeditions nearby. Heavy rain was common, and the area’s cliffs limited exploration. Forster described a waterfall near the harbour, noting its size and the rainbow produced by the spray.[30]

Cook often explored in poor weather and neglected his own health, leading to illness during the stay. Disagreements among the officers occurred, with Forster clashing with many on board. Cook eventually discovered a passage out of the sound, but poor weather and tides delayed their exit. After eleven days, the ship reached open sea and continued north, stopping briefly due to storms before sighting familiar landmarks near Queen Charlotte Sound. On 17 May, as the Resolution approached the rendezvous point near the scattered islands off the coast, the crew observed several water spouts. These were a familiar phenomenon in New Zealand’s coastal waters and usually harmless. Six or seven water spouts appeared in total, but all except one dissipated quickly. The remaining spout was much larger, described as a powerful column of water that reached all the way to the clouds and measured about sixty feet wide at its base. Its motion was unpredictable, and as it moved closer, the crew realized that if it struck the ship, it could destroy the masts and upper structures.[31]

The water spout passed dangerously close—within about fifty feet of the stern—causing great alarm among the crew. However, it eventually changed direction and moved away from the ship, much to everyone’s relief. The following day, the Resolution was six leagues east of Cape Farewell. Cook noted a spacious bay, which he identified as Murderer’s Bay, the site where Tasman had lost four men in 1642. Soon after, the ship passed Cape Jackson and the crew saw a reassuring sign: flashes from two guns, followed by distant thunder, which they recognized as signals from the Adventure. Lieutenant Kempe brought out a boat from the Adventure to greet the Resolution, as the wind had dropped and towing was necessary to make progress. The Resolution dropped anchor in Ship Cove, and Captain Furneaux of the Adventure came aboard. The officers and crew exchanged news and reports after their long separation.[32][33]

Cook decided not to visit Van Diemen’s Land himself because Furneaux had already addressed the question to his satisfaction. Instead, Cook planned to use the winter to explore uncharted seas to the east and north. He proposed this plan to Furneaux, who agreed and began preparing his ship as directed. While waiting, Cook inspected and expanded the gardens, encouraged local people to care for them, planted various crops, and released goats, hoping to establish new animal populations. He also observed the habits and social divisions of the New Zealanders and commented on the effects of European contact, expressing regret about some consequences. Cook and the officers celebrated the king’s birthday with a dinner and festivities, including a double rum allowance for the crew and a gun salute.[34]

Scientific work continued, with observations from Mr Bayly bringing unexpected results about longitude, suggesting a discrepancy in Cook’s earlier charts. Cook noted the difference and reflected on the nature of such errors, ultimately concluding that the impact on navigation was minor. By early June, both ships were ready to depart. Cook outlined his planned route to Furneaux in writing: he would sail east between 41° and 46° south latitude to longitude 140° or 135° west, then head to Tahiti if no land was found, and return to New Zealand before venturing south again. The goal was to cover areas not previously explored and to clarify if any continent existed in these regions.[35]

Bad weather delayed departure for two days, but on 7 June both ships left port. The next day, the Resolution’s chronometer failed, but the Adventure’s was still functional, and the Harrison-Kendall watch continued working. The weather at sea was harsh, with frequent gales, rain, and high seas, but no ice. The challenging conditions caused damage and discomfort, including a goat falling overboard and dying after being rescued. Cook monitored the ships’ positions closely, comparing longitudes and noting the ongoing differences in measurements from various observers. The ships sailed south to latitude 46°56’ before Cook altered course to the northeast and then east, gradually reducing latitude over a wide range of longitude. By 17 July, he had crossed the fortieth parallel at 133°30’ west, having covered the intended area. He then turned north to examine the remaining unexplored zone that might contain a continent.[36]

After more gales, the weather improved, but cases of scurvy began to appear on the Adventure.[37] The ship’s cook Murduck Mahony died on 23 July, and by the time Cook learned about the illness, many were sick.[38] Cook sent a new cook and gave Furneaux advice on managing the outbreak. The Resolution’s crew also had a few mild cases, but most were already on special diets. Furneaux’s crew suffered more, possibly due to overcrowding and a lack of exercise. Cook’s ship crossed Carteret’s track and then his own from earlier voyages, but found no signs of a southern continent. He determined that more investigation was needed but postponed further exploration in favor of reaching Tahiti to refresh the crew. Cautious sailing was necessary due to the condition of the men. On 11 August, the ships sighted an atoll, Tauere, followed by several other dangerous reefs and islands in the Tuamotus. Careful navigation allowed them to avoid these hazards. By 15 August, the mountains of Tahiti were visible, and Cook prepared to stop at Vaitepiha Bay for rest and resupply before continuing to Matavai Bay.[39]

Tahiti

The Adventure was in such poor health that Furneaux had to request extra crew from the Resolution just to operate his ship. As they neared Tahiti, Cook estimated the shore to be about eight leagues away. He sailed until midnight, then stopped until 4 a.m. before heading in toward land. When Cook woke at dawn, he discovered the ship was perilously close to the reef—only about half a league away—due to a navigational error, possibly by a sleepy officer. He ordered the ship to change course immediately, but the wind died, and the current began to carry both ships dangerously towards the reef. With the situation worsening, the crews tried towing with boats and trading with Tahitians who had already come alongside in canoes. By early afternoon, they were near a gap in the reef, but it was too shallow and only drew them closer to danger. Cook tried to use one of the Admiralty’s new warping-machines, but it failed. He dropped anchor, but the Resolution still drifted into shallow water where the sea broke close under her stern, and she began to strike the bottom. The Adventure was also in trouble, nearly colliding with the Resolution until its anchors held.[40]

Cook managed to save the Resolution by cutting away a main anchor and hauling in others, along with a massive effort from the crew. A light wind from the land finally allowed them to get clear, and by 7 p.m. they had moved out two miles. The Adventure also escaped, though she lost three anchors, a cable, and two hawsers in the process.[40] It was a nerve-wracking twelve hours for everyone, especially Cook, who was seen shouting and stamping about the deck in a display his men called a “heiva” a Tahitian word for a lively dance, but soon a term for his growing rages. His usually calm demeanor was showing cracks under the strain. After the ordeal, Cook went to the Ward Room with Sparrman, who found the captain exhausted and in pain. Sparrman gave him a dose of brandy, which revived him, and after a good meal, Cook soon recovered. Cook himself did not mention this episode, only that they spent a squally, rainy night making short boards[41]before anchoring at Vaitepiha Bay around noon the next day.[42]

The main reason for stopping at Vaitepiha Bay, in the Tautira district, was to get the Adventure's sick men ashore for fresh food and rest. Only one of Cook’s own crew, marine Isaac Taylor, died of unrelated causes and was buried at sea. The rest, under the care of a surgeon’s mate, quickly improved with the local diet. Cook also tried to recover lost anchors, retrieving the Resolution’s, but the Adventure’s were unrecoverable.[43] Tahiti had recently been through a civil war. The King, Toutaha, and other principal friends of Cook had been killed, and Otoo was now the reigning prince. The war had also disrupted hog breeding, disappointing Cook’s hopes of obtaining supplies. However, Tahitian habits of thieving and fear of firearms persisted. On the first day, as Cook tried to show goodwill by inviting chiefs into his cabin, they began stealing anything moveable. A cannon shot cleared the crowd, but they returned later as if nothing had happened.[44]

Once ashore, the Adventure’s scurvy cases improved rapidly, and Cook decided to leave Tautira on 24 August.[45] At Matavai Bay on 26 August, Cook met chief Maritata, who promised to introduce him to Prince Otoo. The next day, Cook and Furneaux visited Otoo, finding him surrounded by family and subjects, all naked—a sign of respect. Cook gave Otoo superior gifts (axes, mirrors, beads, medals), which the prince accepted, though he refused to trade his own gifts of cloth, stating his were offered for friendship. Furneaux presented Otoo with a pair of goats, but Cook’s gift of a broadsword frightened Otoo, who asked for it to be taken away.[46]

Relations with Otoo and his wife were warm, though at first Otoo was reluctant to board the Resolution out of fear of the ship’s guns. Cook noted that Otoo seemed a cautious, even timid, prince. On 30 August, a disturbance broke out on shore. Cook sent marines to investigate and found some of his men and a marine from the Adventure had been absent without leave, drunk, and fighting with the Tahitians—reportedly over women. They were punished with lashes. The next morning, the shore was deserted, and Otoo was nowhere to be found. Before leaving, Cook tracked him down to apologize for his men’s behavior and to say farewell. Otoo complained but was mollified by gifts and responded with hogs and gestures of goodwill.[47]

This episode led Cook to reflect on Tahitian women. He criticized reports that all Tahitian women were promiscuous, explaining that as in any society, only some women were prostitutes and that these women were not shunned by their community. Cook insisted on treating all island women with respect, in contrast to the common practice among European sailors of the time, who saw sex with indigenous women as a “reward” for their voyages. Cook believed it was wrong to expose locals to sexually transmitted diseases or treat them differently from women at home.[48] With his men recovered, Cook decided not to overstay. On 3 September, both ships set sail for Huahine and Raiatea.[49]

Cook had spent over two weeks at Tahiti, using this time to compare his observations with those of earlier explorers like Bougainville. He specifically investigated claims of human sacrifice and, with the help of interpreters, learned that such practices did exist, although his confidence in the accuracy of this information was limited by language barriers. The English showed little reaction to this discovery, especially compared to their response to reports of cannibalism in New Zealand. The Forsters, who were less cautious than Cook, analyzed Tahitian society and recognized that it was structured along class lines. George Forster argued that class differences were mostly ceremonial, due to the ease with which people could meet their basic needs.[50]

However, he predicted that growing inequality and the introduction of foreign goods would eventually cause social tension and change. He worried that European contact would bring negative consequences for Tahiti. Other members of the crew had their own perspectives. Some praised Tahiti as a paradise, while others, like Wales, disagreed and criticized the romanticized view. Wales also defended Tahitian women from being labeled immoral, noting that shipboard experiences gave a skewed impression. Cook took a pragmatic approach to Tahitian customs, believing that sexual conduct among unmarried people was not harmful to society. He became more tolerant toward theft, only insisting on strict measures when necessary to maintain order. When the expedition left the islands, they took with them two Tahitians: Omai joined the Adventure, motivated by a desire for prestige and to help his home island of Raiatea, while Porio joined the Resolution, seeking status through association with the English.[51]

Society Islands and Tonga

At Huahine, Cook was warmly received by the chief Ori, who had hosted him before. Trade with the islanders was brisk, and the ships were able to acquire a large number of hogs and other provisions. However, theft remained common, and there were more serious incidents involving violence against members of the expedition. At Huahine, Anders Sparrman, went ashore alone to collect plant specimens. Two local men offered to guide him, but instead they attacked him, stripped off his clothes, stole his knife, and chased him along the beach. Sparrman managed to escape and return to the ship, shaken and nearly naked.[c] Cook was more upset with Sparrman for going off alone than with the attackers. However, Johann Forster sided with Sparrman, believing his life had been put at risk.[52]

A similar event occurred at Raiatea. George Forster became separated from his group while trying to hire a canoe to return to the ship. A local man seized George’s gun. Johann Forster, witnessing this, rushed to his aid, and the attacker quickly returned the weapon and fled. Johann gave chase and fired at the man, but the incident ended without further violence. Back on the ship, some crew members criticized Johann for overreacting. Johann accused Cook of not protecting the scientific staff, while Cook felt the Forsters were partly responsible for making themselves vulnerable. The disagreement led to a heated argument between Cook and Johann Forster, who was asked to leave Cook’s cabin. The two men later reconciled after a formal exchange. After leaving Raiatea, Cook took a different route back to New Zealand, aiming to locate islands previously charted by Abel Tasman and to prepare for more exploration in the Antarctic region.[53]

Two weeks later, Cook and his crew reached islands identified as Eua and Tongatapu. Upon arrival at Eua, they were greeted by crowds of islanders in outrigger canoes, who greeted the English by rubbing noses.[54] The English were surprised at this familiarity, assuming that any memory of Tasman’s earlier visit would have faded. The Forsters learned local names for the islands and noted that Eua, while less striking geographically than Tahiti, was carefully cultivated and laid out in lawns and gardens. The houses and fences showed a high level of craftsmanship and order, suggesting a carefully managed system of private property and agriculture. The English noted that Eua was less wealthy than Tahiti. Houses and canoes were smaller and more detailed, clothing was simpler, and there was little surplus food. The residents seemed hesitant to trade provisions, likely because their resources were limited. [55]

At Tongatapu, the English received a warm welcome, and the islanders quickly came to trade. Initially, they offered only cloth and curiosities, but after the English made clear their interest in food, the next day saw canoes full of provisions brought out. The visitors spent three days on the island, acquiring food and exploring. Like Eua, Tongatapu was highly cultivated, with every piece of land used efficiently, and houses, canoes, and baskets displayed impressive craftsmanship. During their stay, several incidents occurred involving theft and attempted theft by the islanders. Wales had his shoes stolen on the beach, but a chief promptly returned them. More seriously, one group tried to take one of the Resolution’s boats, and another man stole books from the master’s cabin and escaped by canoe.[56]

When pursued, the thief threw the books overboard. The sailors recovered them, and after a chase involving diversions and attempts to disable the English boat, the thief was caught and pulled into the boat but managed to escape by swimming ashore. Cook unlike to Tahiti responded to theft by ordering harsh punishments: muskets were fired at a man who stole an officer’s jacket, and others were tied up and flogged. The local people did not appear upset by these actions and continued trading as before, seemingly accepting that thieves should face consequences. The English noted many similarities between the Tongans and the Tahitians, including physical appearance, tattooing, clothing, and religious practices. However, they also remarked on key differences. The Tongans’ society appeared more egalitarian, with few visible class distinctions and a culture shaped by the necessity to work hard for food due to limited resources. [57]

Chiefs were respected but did not demand tribute or labor as in Tahiti, and even participated in manual work. The Forsters theorized that these differences in environment and resource availability shaped local customs, social structures, and attitudes toward work and authority. The Tongans impressed the English with their skills in agriculture, crafts, and their polite, generous behavior. The Forsters saw them as representing an early stage of societal development, suggesting that increased access to resources and technology could further transform their society. Despite the issues with theft, the Englishmen left with a strong sense of having encountered a well-organized and industrious community, distinct from but related to the societies they had seen elsewhere in the Pacific.[58]

Back to New Zealand and depature of the Adventure

On 8 October Cook set sail bound for New Zealand. After leaving Tongatapu, Cook faced immediate difficulties at sea. In unmooring, he lost an anchor when the cable broke, and another cable was badly damaged by the coral seabed. As the ships prepared to depart, a Tongan canoe brought a drum as a gift; Cook exchanged it for cloth and a nail, and also sent wheat and vegetable seeds to Chief Ataongo, supplementing what he had already given. Sailing on, Cook spotted the high island of ‘Ata, then spent nearly two weeks on open sea in mostly pleasant weather, though the winds shifted from the east and southeast to the north and west after the 17th. The changing winds forced Cook to slow down so the Adventure could keep up. On the night of the 20th, a black rain cloud caused a false alarm for land directly ahead; the night was so dark that guns were fired and false lights shown to keep the ships together. By morning, New Zealand was in sight near Table Cape.[59]

Cook aimed to distribute domestic animals and seeds to the Māori as far north as possible, believing that the people in the north were more “civilized” and better able to care for these gifts. However, no Māori approached the ships until they had traveled some way down the coast from Cape Kidnappers. When canoes finally came out, Cook gave the chief a large spike nail, which caused great delight, as well as pigs, chickens, and a variety of seeds. The chief promised not to kill the animals and accepted the seeds, but it was the nail that impressed him most. Cook hoped these gifts would benefit the region — his cabbage, in particular, would go on to be cultivated along the coast.[60]

Soon after the exchange, a powerful gale from the north and west struck on October 22. It was one of the relentless spring storms common to Cook Strait, with brief lulls and sudden switches in wind direction. The storm destroyed the Resolution’s fore topgallant mast, shredded sails, and forced the crew to repeatedly reef and unreef the sails as the weather shifted. On October 25, the storm intensified so much that all sails had to be taken in, and the ship lay-to under bare poles, tossed by immense waves but safe from a lee shore. The Adventure was blown to leeward but eventually found again. For days, the ships struggled to make progress, beating up and down or lying-to as the weather allowed. In the early hours of October 30, the two ships parted company for the final time. On October 31, the Resolution was off the Kaikoura mountains in the South Island, enduring the storm’s greatest fury and forced once again to lie-to under a single sail. At midnight, the weather calmed somewhat and shifted; by November 1, Cook was able to navigate through Cook Strait, aiming for Queen Charlotte Sound, but another gale rose, splitting most of the sails. He anchored for the night, and by morning, with a new breeze, made his way to Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound, arriving on November 3 — but the Adventure was not there.[61]

Cook’s crew immediately got to work repairing the ship: cleaning inside and out, fixing sails and ironwork, overhauling rigging, caulking, collecting wood and water, and salvaging what they could of the ship’s biscuit, much of which was rotten and had to be destroyed or rebaked. Cook blamed this on unseasoned timber in the casks and the effects of storing ice in the hold followed by tropical heat. Ballast and coal were also shifted to keep the ship seaworthy. During this period, Cook worried about the Adventure’s absence, unable to explain it satisfactorily. He suspected Furneaux might have given up battling the storms and headed for the Cape of Good Hope. On November 24, Cook left a message in a bottle at the watering place, buried under a tree marked Look underneath describing his intended plans but giving no fixed rendezvous point, only a rough idea that he might head for Easter Island around March, or possibly Tahiti or another Society Island, depending on circumstances.[62]

On November 25, the Resolution set sail again, searching for Adventure by firing guns and looking into bays along the North Island coast. Failing to find her, and with his officers agreeing that Adventure was likely gone, Cook decided to proceed with his exploration of the southern Pacific. He left Cape Palliser on November 26, heading southeast.[63] Meanwhile, the Adventure had faced its own struggles. After being separated from the Resolution during the storm, Captain Furneaux made landfall near Cape Palliser and was able to trade with the Māori for crayfish and provisions. The Adventure was in poor condition, with leaking decks and worn rigging. Bad weather repeatedly drove the ship back along the coast, at one point as far as Tolaga Bay, where they took on wood and water. For two weeks, the Adventure struggled to clear the headlands and make progress, but the wind and sea conditions were against them.[64]

Eventually, on November 30, the battered Adventure limped into Ship Cove, too late to meet the Resolution. Furneaux found Cook’s message under the marked tree. The message contained no specific instructions, only vague references to possible future movements, and left Furneaux to decide his own course. After discussing with his officers and considering the poor state of his ship, Furneaux decided that searching the Antarctic seas for the Resolution was impossible.[65]

On December 17, Furneaux noted the readiness of his ship for sea, having refitted it and secured provisions for the crew to avoid scurvy. He dispatched a cutter with Mr. Rowe and a crew to gather wild greens but grew concerned when they did not return the next evening. Jem Burney was subsequently ordered to search for them, inspecting various coves until they reached a bay populated by frightened Maoris. Burney attempted to calm them with gifts, but tensions remained as one Maori approached with spears before leaving them behind and walking away Burney grew increasingly alarmed upon discovering items belonging to the cutter's crew at the settlement, including a rullock port and shoes known to belong to midshipman Mr. Woodhouse. A local offered him what was initially thought to be salted meat, but upon inspection, it was determined to be fresh, leading Burney and Mr. Fannin to suspect it was dog's flesh. Despite hoping the locals were not cannibals, they were soon presented with undeniable evidence that confirmed their worst fears.[66]

A search on the beach revealed about twenty open baskets containing roasted flesh and fern root. Additional findings included shoes and a hand identified as belonging to Thomas Hill. They discovered a freshly buried spot in the woods but lacked a spade to dig. As they launched a canoe to destroy it, they noticed smoke rising from a nearby hill and hurried back to the boat before sunset. In Grass Cove, upon arrival, the English encountered four canoes and a crowd of Native people who quickly retreated to a nearby hill. A large fire was visible at the top of the hill, where the area was bustling with activity. As the English approached, they fired a musquetoon at the canoes, suspecting they contained hidden men. [67]

The Native people on the hill made signs for the English to land, but as the English drew closer, they opened fire on the Natives. The first volley had little effect, but on the second, the Natives began to flee. After landing, the English discovered bundles of celery and a broken oar, indicating a previous engagement. However, a grim scene awaited them along the beach bodies of several English soldiers were found horrifically dismembered, with dogs gnawing at the remains, showcasing a gruesome act of violence. In a state of disgust and anger, Burney's men destroyed the canoes while hearing voices from the forest, which Burney assumed indicated an impending attack. As night fell and rain began, four of the muskets misfired, leading Burney to conclude that they were gaining little by staying, prompting them to retreat back to the ship.[68]The Adventure setting out for home on 22 December 1773 via Cape Horn, arriving in England on 14 July 1774.[69]

Re-crossing the Antarctic circle

By December, Cook and the crew of the Resolution were deep in the Southern Ocean, heading toward the Antarctic. On 7 December, they reached approximately 51°30' S, 180° longitude—almost exactly opposite London on the globe. The only signs of life were a few penguins and petrels amid vast stretches of sea. The Forsters and astronomer William Wales marked the moment with a toast to their friends far away, directly beneath them on the earth’s surface. On 12 December , they sighted their first iceberg, and three days later, the ship encountered its first pack ice. The Resolution pressed on southeast, crossing the sixtieth parallel before steering east. Despite some fog, fair winds let them cover 60–100 miles per day. By Christmas 1773, as the latitude approached 65° S, the cold became intense: icicles formed on the ship’s superstructure, sails stiffened with ice, and ropes became rigid and hard to use. Changing a sail was a punishing ordeal, but the crew pushed through the hardship.[70]

For the rest of December, Cook steered first northeast, then north. By January 2, 1774, the Resolution was at latitude 57° S, longitude 136° W—about 560 miles north of its Christmas Eve position. On January 11th, concluding there was no land between his position and Tahiti, Cook turned southeast again. Provisions were running low, and as stores were opened, much of the food was found to be rotten or inedible. Cook reduced rations to make supplies last until March, when he hoped to reach Easter Island, but the reduced food caused unrest. On 17 January, the first mate burst into Cook’s cabin brandishing a piece of rotten biscuit, sarcastically asking how he was supposed to fill his belly. Sensing real discontent, Cook immediately restored full rations.[71]

Tensions persisted. Johann Forster, disgusted with Cook’s leadership and the miserable conditions, retreated to his cabin on January 23 and did not reappear until the end of the month. His journal was filled with complaints about Cook’s ambition and secrecy, the appalling food, constant damp, and the endless storms. His son George agreed that Cook rarely confided in his officers, which fueled the sense of isolation.

On January 26, the Resolution crossed the Antarctic Circle for the third time and pushed south for several days. “God knows how far we shall still go on,” complained Johann Forster, “if Ice or Land does not stop us, we are in a fair way to go to the pole & take a trip round the world in five minutes.” On the morning of 30 January, the crew sighted a wall of ice stretching across the horizon, with mountains of ice rising to the clouds—so many that Cook counted ninety-seven.[72][73] On this occasion, Cook wrote:

I who had ambition not only to go farther than anyone had been before, but as far as it was possible for man to go, was not sorry in meeting with this interruption...

The pack ice was too dense to penetrate, and beyond it lay an unbroken sheet, which Cook speculated might extend to the South Pole. Recognizing the futility and danger, Cook ordered the ship to turn back north. At 71° S, this was the southernmost point reached on the voyage—a record for the era.[72]

Cook admitted that trying to force through the ice would be reckless, even for someone as ambitious as himself. He noted that the encounter with the ice “relieved us from the dangers and hardships, inseparable with the Navigation of the Southern Polar regions.” He concluded there was almost certainly no land between this point and Cape Horn, so he set course north for the tropics. Despite his reputation for persistence, Cook was not reckless; he recognized when it was time to turn back. Yet Cook was not ready to return home. He intended to continue exploring for another year, reasoning that it would be an abdication of duty to leave the South Pacific unexplored when so many islands were imperfectly charted. He planned to head west to Easter Island, then to the islands discovered by Mendaria, Quiros, and Bougainville in the western Pacific, before eventually making for Cape Horn and home.[74]

Heading north proved wise, as several crew members showed early symptoms of scurvy. Johann Forster pessimistically predicted many would die before reaching the tropics, but in fact, no one died and most recovered. However, Cook himself fell dangerously ill with severe stomach pains and what was likely an intestinal obstruction, possibly from a parasite. For several days, he was near death, barely able to eat or walk. When he recovered enough to take food, Johann Forster sacrificed his Tahitian dog for the captain’s broth. In mid-March 1774, after three months without sighting land, the Resolution finally saw a small island on the horizon. Cook soon recognized it as Easter Island by its location and the distinctive stone statues visible from afar. For the weary crew, the sight of land—however small—offered hope of fresh food, water, and rest after their ordeal in the Antarctic.[75] The vessel was then launched north to complete a huge arc in the Pacific Ocean, reaching latitudes just below the Equator then New Guinea. He had landed at the Friendly Islands, Easter Island, Norfolk Island, New Caledonia, and Vanuatu before returning to Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand.[76]

Remove ads

Homeward voyage

Summarize

Perspective

On 10 November 1774 the expedition sailed east over the Pacific and sighted the western end of the Strait of Magellan on 17 December. They spent Christmas in a bay they named Christmas Sound on the western side of Tierra del Fuego. After passing Cape Horn, Cook explored the vast South Atlantic looking for another coastline that had been predicted by Dalrymple. When this failed to materialize they turned north and discovered an island that they named South Georgia. In a last vain attempt to find Bouvet Island Cook discovered the South Sandwich Islands. Here he correctly predicted that:

...there is a tract of land near the Pole, which is the Source of most of the ice which is spread over this vast Southern Ocean.[77]

Later, in February 1775, he called the existence of such a polar continent "probable" and in another copy of his journal he wrote:

[I] firmly believe it and its more than probable that we have seen a part of it.[78]

On 21 March 1775 Resolution anchored in Table Bay, there to spend five weeks as her rigging was refitted. She arrived home at Spithead, Portsmouth on 30 July 1775 having visited St Helena and Fernando de Noronha on the way.[79]

Return home

Cook's reports upon his return home put to rest the popular myth of Terra Australis.[80] Another accomplishment of the second voyage was the successful employment of the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer, which enabled Cook to calculate his longitudinal position with much greater accuracy. Cook's log was full of praise for the watch which he used to make charts of the southern Pacific Ocean that were so remarkably accurate that copies of them were still in use in the mid-20th century.[81] Cook was promoted to the rank of captain and given an honorary retirement from the Royal Navy, as an officer in the Greenwich Hospital. His acceptance of the post was reluctant, insisting that he be allowed to quit the post if the opportunity for active duty presented itself.[82] His fame now extended beyond the Admiralty and he was also made a Fellow of the Royal Society and awarded the Copley Gold Medal, painted by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, dined with James Boswell and described in the House of Lords as "the first navigator in Europe".[83]

Remove ads

Publication of journals

On his return to England, Forster claimed that he had been granted exclusive publication rights to the history of the voyage by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich – a claim that Sandwich vehemently denied. Cook was writing his own account assisted by Dr John Douglas, Canon of Windsor. Eventually, Sandwich agreed that Forster and his son could add a scientific section to Cook's account of the voyage. This led to so much animosity between Forster and Sandwich that Sandwich banned him from writing or publishing anything about the voyage. To avoid the ban, Forster's son Georg wrote a report instead, titled A Voyage Round the World, which was published in 1777, six weeks before Cook's account appeared. Cook never read Forster's book because it was published after he left on his third voyage, from which he did not return.[84] Some of the botanical results of the voyage were published by the Forsters as Characteres generum plantarum in 1776, with earlier 1775 copies given to King George III and to Carl Linnaeus.[85]

Remove ads

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads