Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Johannine literature

New Testament works traditionally attributed to John the Apostle or to a Johannine circle From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Johannine literature is a modern collective term for five New Testament writings that early Christian tradition linked in various ways with John the Apostle or a related circle of teachers: the Gospel of John, the three Johannine epistles (1 John, 2 John, and 3 John), and the Book of Revelation. The designation identifies a literary family with shared vocabulary and theology without implying single authorship, and it reflects how ancient readers grouped the texts while acknowledging distinct voices within them.[1][2][3][4]

Current scholarship usually dates the Gospel and Letters to the final decades of the first century, often AD 90–110; some pursue earlier signs and editions, while recent scholarship increasingly views the gospel as a literary unity by a single author.[5][6][7][8][9] Revelation is most often dated within the reign of Domitian (AD 81–96) because of its address to seven assemblies in Roman Asia and its critique of imperial cult imagery, though a minority advocates an earlier context in the late 60s under Nero or Galba.[3][10][11][12]

Patristic witnesses variously attribute the corpus to John, yet modern scholarship largely distinguishes the author of Revelation from the writers behind the Gospel and Letters. A a Johannine school or community that produced the latter documents and preserved the voice of an Elder figure has been proposed, but the idea of a Johannine community has been increasingly challenged, and there is no consensus among scholars today.[4][1][3][13][14] Debate continues over how the materials relate to the historical John the Apostle, but the prevailing view separates the seer of Patmos from the Evangelist and explains the similarities among the Gospel and Letters through shared tradition and collaborative redaction.[4][5]

The five writings converge on core motifs of Jesus as the revealer sent from the Father, the witness of the Spirit, contrasts of light and darkness, and communal tests of love and truth, even as their genres generate different emphases, from the Gospel's narrative irony to Revelation's apocalyptic visions and the Letters' boundary setting exhortations.[2][8][3][10] The works combine theological coherence with internal diversity that continues to shape scholarly interpretation.[1][15]

Remove ads

Works

Summarize

Perspective

Johannine literature is traditionally taken to include the following five writings.[1][2]

- The Gospel of John

- The Johannine epistles

- The Book of Revelation

The Gospel of John is a narrative Gospel that combines public signs and extended discourses to present Jesus as the incarnate Word who reveals the Father.[2][5] 1 John reads as a sermonic circular that reinforces confession of the Son, obedience, and love in the face of schism.[8][16] 2 John is a brief admonitory letter warning a chosen congregation about itinerant deceivers and urging hospitality governed by truth.[8][17] 3 John is a personal letter commending faithful emissaries, censuring Diotrephes, and modeling the networked authority of the Elder.[17][16] Revelation is an apocalypse in epistolary form that addresses seven assemblies with visions of judgment, worship, and the renewal of creation.[3][10]

Literary style and structure

Scholars describe the Gospel of John as unfolding in a Book of Signs (John 1–12) followed by a Book of Glory (John 13–20), where seven public signs lead into extended discourses and culminate in passion and resurrection scenes. The Gospel also contains seven "I am" sayings, concluding with Thomas's confession "my Lord and my God," a title also used by Emperor Domitian (AD 81-96).[2][6][7][5]

When he had said this, he cried with a loud voice, "Lazarus, come out!" He who was dead came out, bound hand and foot with wrappings, and his face was wrapped around with a cloth. Jesus said to them, "Free him, and let him go." John 11:43-44 [18]

Jesus said to them, "I am the bread of life. He who comes to me will not be hungry, and he who believes in me will never be thirsty." John 6:35 [19]

The narrative layers dramatic irony, misunderstanding, and inclusio, so that themes voiced in the prologue reappear in closing testimonies and the Beloved Disciple's witness frames the plot.[2][6]

Jesus answered him, "Most certainly, I tell you, unless one is born anew, he can't see God's Kingdom." Nicodemus said to him, "How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter a second time into his mother's womb, and be born?" John 3:3-4 [20]

Scholarship has turned against positing hypothetical sources for John,[21] with most today finding the existence of a single source for the miracles in John unlikely.[22] Many scholars argued the gospel was written by multiple hands due to aporiae or seams such as 6:1 and 14:30, yet the proposals remain contested and no single model has won consensus, and the model of John as a product of multiple editions by a school of writers is in retreat.[7][5][23]

This is the disciple who testifies about these things, and wrote these things. We know that his witness is true. There are also many other things which Jesus did, which if they would all be written, I suppose that even the world itself wouldn't have room for the books that would be written. John 21:24-25 [24]

1 John lacks a conventional epistolary opening and reads like a homily with cyclical argumentation that revisits motifs of confession, obedience, and love to reinforce communal assurance. 2 John and 3 John adopt brief letter forms that identify the sender as the Elder, combine greetings, travel plans, and commendations, and show how the Johannine network negotiated hospitality and doctrinal boundaries.[8][16][17]

The Book of Revelation presents itself as an apocalypse and a circular letter addressed to seven assemblies in Asia Minor, opening with a prophetic commission and embedded messages to each city. Its visions recycle scriptural imagery from Daniel, Ezekiel, and Zechariah, and interpreters debate whether the seal, trumpet, and bowl cycles recapitulate the same period or map a more linear sequence through the End, a discussion that shapes how the book's structure is charted. Revelation's Greek exhibits Semitic interference, abrupt shifts, and deliberate solecisms that distinguish it from the Gospel and Letters while serving its visionary rhetoric.[3][10][11][25]

Intertextual and canonical relationships

Commentaries compare the Gospel of John with the Synoptic Gospels on chronology and content due to its unique style and structure.[26] John distributes Jesus's ministry across three Passovers, places the temple action near the outset, and develops long dialogues with figures such as Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman at the well. The synoptic accounts concentrate the ministry into a single pilgrim Passover, foreground parables and exorcisms, and place the temple demonstration in the final week, so scholars describe John as preserving an independent stream that still shares passion and feeding traditions with the synoptic accounts.[2][6]

Johannine writings rework Israel's Scriptures through christological interpretation. The Gospel invokes creation motifs from Genesis in its prologue, frames Jesus as Wisdom who tabernacles among humanity, and repeatedly cites Isaiah to interpret signs and rejection. Revelation intensifies the pattern by weaving visions from Ezekiel, the Book of Daniel, and the Book of Zechariah into throne scenes, trumpet sequences, and the depiction of the New Jerusalem, while echoing wisdom traditions in its hymns and personifications.[27][3][10]

The Gospel and 1 John gained wide authority by the late second century, as figures such as Irenaeus and the Muratorian fragment quote or list them.[4] 2 John and 3 John circulated more narrowly and were sometimes grouped with disputed writings, while the Book of Revelation was embraced in the Latin West yet questioned by eastern catalogues reported by Eusebius.[4][28] Later fourth century summaries, including Athanasius's Festal Letter of 367, confirmed the inclusion of all five writings in the mainstream canon.[4]

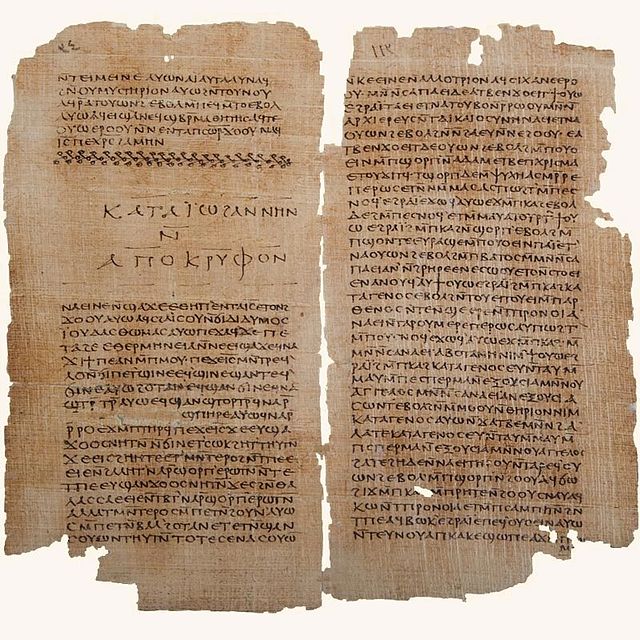

Apocryphal

Second-century Sethian authors in Egypt and medieval dualist movements such as the Bogomils and Cathars extended John's authority to apocryphal narratives and revelatory discourses that circulated outside the canonical corpus, often casting the apostle as a witness to hidden teachings or visionary journeys.[29][30][31] These Johannine apocrypha span settings from second-century gnostic communities to medieval dualist movements, showing how diverse groups appropriated John to articulate theology, liturgy, and communal authority outside the canonical frame.[30][31]

Apocryphal works associated with John include:

- The Acts of John

- The Apocryphon of John (Secret Book of John)

- The Book of the Secret Supper

Remove ads

Historical context

Summarize

Perspective

Irenaeus (AD 130-202) writes that John, the disciple of the Lord, issued his Gospel at Ephesus in Asia, and the same tradition links John to Revelation and to a network of teachers who remained active into the time of Trajan (AD 98-117).[32][4]

Late first century Asia Minor featured major port cities of Ephesus, Miletus, Smyrna, and Pergamon, which hosted extensive networks of Jewish diaspora synagogues and promoted the imperial cult. In these urban centers, public festivals, commerce, and temple patronage intertwined, so minority groups negotiated identity amid pressures to honor Roman power while maintaining their own worship practices.[1][3] The Johannine writings address believers situated in this environment, balancing engagement with synagogue communities and resistance to imperial ideology.[10]

The Gospel hints at synagogue tensions through the rare term aposynagogos ("expelled from the synagogue") in John 9:22, 12:42, and 16:2. Martyn interprets these verses as echoes of real exclusions connected to confession of Jesus as Messiah, whereas studies by J. Andrew Doole and Adele Reinhartz argue that the evidence does not prove a uniform or empire wide policy and may reflect rhetorical dramatization of local disputes.[33][34][35]

Most scholars place the composition of the Gospel of John and 1 John in the last decade of the first century,[36] with some proposing earlier signs and later discourse expansions, and a final editorial hand that framed the epilogue in John 21, though Johannine scholarship has experienced a synchronic turn, and the unity of John 21 with the gospel is also commonly acknowledged.[5][6][7][37][38][39] 2 John and 3 John are often dated around the same period because they presuppose the schism described in 1 John and address travel and hospitality within the same network.[8][16]

Revelation is usually dated to the reign of Domitian (c. 81–96) on the grounds of its letters to seven churches in Asia and its critique of imperial cult imagery, a view supported by Koester, Bauckham, and David Aune.[3][10][25] A minority argues for a context in the late 60s during the time of Nero or Galba, pointing to references to the temple and the number of the beast. Commentators such as Robert H. Mounce summarize the evidence for this earlier scenario while noting its limited following.[11]

The Rylands Library Papyrus P52 (c. 125), an early manuscript discovery, preserves a portion of John 18, while Papyrus 66 (early third century) and Papyrus 75 (early third century) attest to extensive circulation of the Gospel and its stability across Egyptian copyists.[4][5] These witnesses support a late first century origin for the Gospel and show that Johannine writings were disseminated beyond Asia Minor within a few generations of their composition.

Reception and influence

Clement of Alexandria (c. AD 150-215), as preserved by Eusebius, called John a "spiritual Gospel", which signaled a theologically charged reception that prized contemplation and christological depth.[40] Origen (c. AD 185-254) opened his commentary by ranking John as the "first fruits" of the Gospels and linked the Prologue to the work of creation and wisdom.[41] Augustine (AD 354-430) shaped Latin reception with extensive Tractates on the Gospel of John and Homilies on the First Epistle of John, where he grounded moral teaching in caritas and repeated the maxim "Love, and do what you will".[42][43] These early church writings shaped how later Greek and Latin scholars interpreted the Gospel and 1 John, cementing their importance.[4]

In the 4th century, Pro-Nicene theologians drew on John 1 and John 10 for language about the Son and the Father and developed patterns of reasoning that Ayres describes as distinctly "pro Nicene".[44] The Farewell Discourse and the Paraclete sayings influenced trinitarian reflection and catechesis, while monastic and mystical authors developed a spirituality of "abiding" that Louth and Schneiders trace through Lectio divina and communal practice.[45][46][47]

Koester and the Oxford Handbook of the Book of Revelation note uneven acceptance in the Greek East and the book's absence from the Byzantine lectionary, yet they also document its use as prophecy addressed to seven assemblies and as a circular letter for worship and warning.[48][49] Medieval Europe generated commentary cycles and illuminated Apocalypses that translated visions into civic and monastic settings, a tradition mapped by Emmerson and Bernard McGinn.[50] Reformation era assessments diverged sharply. Martin Luther's early preface called Revelation "neither apostolic nor prophetic", while later Protestant and Catholic readers harnessed its symbols for polemic, consolation, and reform.[48][50]

The Beatus tradition of illuminated manuscripts emerged in medieval Spain during the 8th-10th centuries, while English Apocalypse manuscripts flourished in the 13th-14th centuries, using illustrations alongside texts.[50] Biblical phrases such as "Worthy is the Lamb" and the Prologue's language of light and word entered Western hymnody and oratorio, and musicologists document sustained borrowing from John and Revelation across liturgy and concert repertoire.[51]

Boyer describes how American premillennial and dispensational traditions read Revelation's beasts, millennium, and New Jerusalem as a program for "end time" chronology and piety.[52] Wessinger's handbook surveys millennial groups that invoked Revelation to interpret crisis and to organize communal discipline and hope.[53]

Remove ads

Authorship and attribution

Summarize

Perspective

The five works traditionally attributed to John use different methods of attributing authorship, and later tradition disambiguates several figures named John.

The Gospel invokes the unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved", later identified with John the Apostle or John the Evangelist, while Revelation introduces John of Patmos as its seer. 2 John and 3 John name their sender as "the Elder", a title that some patristic authors associated with John the Presbyter.[2][8][54]

Irenaeus reported that the apostle John published the Gospel at Ephesus and linked him with Revelation and teachers active until the reign of Trajan.[32][4] Papias of Hierapolis, as quoted by Eusebius, listed both a John among the Twelve and another John called the elder, a tradition that later interpreters used to distinguish the Evangelist from the Elder.[54] Dionysius of Alexandria, whose observations Eusebius transmits, appealed to differences in vocabulary and syntax to argue that Revelation could not come from the same hand as the Gospel and Letters.[28]

Modern scholarship generally agrees that the Gospel of John and the Book of Revelation stem from different authors, citing contrasts in Greek style, imagery, and theology.[3][10] 20th century scholarship largely posited a Johannine school or circle that composed the Gospel in editorial stages, but recent scholarship tends to view John as the product of a single author, and the existence of the Johannine community has been challenged.[6][7][5][55][56]

The Elder who signs 2 John and 3 John is often identified as a leader within that circle whose teaching shaped 1 John. Arguments for this view point to shared vocabulary, antichrist polemic, and the emphasis on hospitality and truth across the Letters.[8][17][16] Others, including Charles Hill and Francis Moloney, defend closer authorship ties to the apostolic John and treat the Elder as another title for the Evangelist, while a minority view, exemplified by Hugo Méndez, regards the Elder as a literary persona that lends authority to composite writings.[4][2][13]

As with other features of the Johannine corpus, stylistic similarities exist alongside variation, so debates about attribution remain open even while most scholars distinguish the seer of Patmos from the Evangelist.[2][8]

Remove ads

Johannine community

Summarize

Perspective

Since the mid-twentieth century scholars described a Johannine community that produced the Gospel and Letters and that negotiated conflict with local synagogue authorities and internal dissenters.[5][33][16] This interpretation, which saw the community as essentially sectarian and standing outside the mainstream of early Christianity, has been increasingly challenged in the first decades of the 21st century,[57] and there is currently considerable debate over the social, religious, and historical context of the gospel.[58] Scholars including Adele Reinhartz and Robert Kysar have challenged the idea of a Johannine community, and there is no consensus among scholars today.[59][60][61]

Raymond E. Brown condensed the evidence into a four phase sequence: an initial mission to the synagogue, a stage of confrontation marked by the aposynagogos notices in John 9:22, 12:42, and 16:2, an internal split in which former members depart as narrated in 1 John 2:18–19, and a final consolidation visible in 1 John, the commissioning of the Beloved Disciple in John 21, and the commendation of Demetrius in 3 John 12.[62]

Martyn developed a two-level drama reading that intertwines Jesus's ministry with the later experience of the Johannine believers. He related the expulsion episodes in John 9 and 16 to the debated Birkat haMinim petition that may have sharpened synagogue boundaries, while stressing how the narrative gains rhetorical force from those parallels.[33] Later reassessments, including studies by J. Andrew Doole and Adele Reinhartz, accept that the Gospel registers social strain yet question whether the Birkat was uniformly applied or chronologically prior to the Gospel's final form.[34][35][63]

Harold W. Attridge and Hughson Ong describe the Johannine network as a community of practice or school with porous boundaries, a model that fits the travel logistics and hospitality disputes reported in 3 John 9–10.[64][65] Hugo Méndez goes further, arguing that the Gospel and Letters fashion a literary persona through pseudonymous correspondents, so that the secessionists of 1 John and the elder's opponents in 3 John function as rhetorical interlocutors rather than transparent reports of a discrete congregation.[13]

Despite divergent models, discussion turns on the same textual markers: the aposynagogos refrain in John 9, 12, and 16, the secession and testing language in 1 John 2:18–27 and 4:1–3, and the contested authority reflected in 3 John 9–12.[33] These passages ground historical reflection while underscoring both the cohesion and fragility that the Johannine writings seek to address among their circles of readers.[8][16][34]

Remove ads

Theology and major themes

Summarize

Perspective

Scholars often speak of a shared Johannine voice, one that calls for abiding, bears witness, and keeps eschatological hope alive, at the same time they stress that the Gospel, the Letters, and Revelation weave these motifs into pastoral situations that differ in scope and urgency. The thematic sketches that follow, Christology, dualism and symbolism, pneumatology, eschatology, and ecclesiology, trace how this common vocabulary is translated into narrative artistry, communal guidance, and apocalyptic imagination across the Johannine corpus.[1][66]

Johannine writings frame salvation as life from above that the Father gives through the Son and in the Spirit. They stress revelation, witness, and the call to believe, and they define communal identity through love, obedience, and discernment of truth. Symbolic language, especially in the signs, and narrative misunderstandings invite readers into deeper recognition of Jesus and his mission.[37][6][8]

Christology

Johannine Christology opens with the Prologue (John 1:1–18), where the Word (λόγος) preexists with God (πρὸς τὸν θεόν), shares the divine identity, and becomes flesh (σὰρξ ἐγένετο) to dwell among humanity.[5] The passage joins incarnation to revelation of glory (δόξα) as the only Son who interprets the Father, establishing the pattern whereby the Gospel's signs disclose divine presence in the Son.[67]

Across the narrative Jesus interprets his mission through the absolute "I am" (ἐγώ εἰμι) declarations and the predicate sayings that associate him with life, light, and shepherding.[68] These claims, alongside titles such as Lamb of God, Son of Man, Messiah, Son of God, Kings of Israel and Judah, and Lord, embed Jesus in Israel's Scriptures while presenting his glorification in the cross and resurrection as the hour when the Father's glory is manifested.[69][70]

The Johannine Letters protect this confession by insisting that every spirit must acknowledge that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh (ἐληλυθότα ἐν σαρκί) and by applying tests of truth based on confession, ethical practice, and love.[8] They warn against deceivers labeled Antichrist and link abiding in God with confessing the incarnate Son, thereby countering docetic tendencies and safeguarding the community's christological boundaries.[16]

Revelation employs apocalyptic imagery to portray Jesus as the faithful witness, firstborn of the dead, and ruler of kings, and to enthrone the slain yet standing Lamb (ἀρνίον ἐσφαγμένον) beside God.[3] Hymns and visions show the Lamb sharing divine worship while leading judgment and renewal, offering a complementary picture to the Gospel's dialogues by emphasizing victory through sacrificial suffering and royal authority over the nations.[10][71]

Dualism and symbolism

Johannine writings work with a pronounced dualism of light and darkness, truth and falsehood, above and below, yet they resist the rigid determinism found in Qumran dualism.[72] The contrasts invite decision rather than portray predestined factions, and they remain open to transformation through belief and abiding in the Son.[73] The Letters extend this moral dualism by measuring discipleship through obedience, love, and confession, so that walking in light becomes a communal vocation.[8]

Irony and misunderstanding operate as narrative strategies that draw readers into deeper insight with characters such as Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman at the well misconstrue Jesus's words about birth, water, or worship, allowing the narrative to reveal layered meanings that point beyond literal categories.[6][74]

Recurring symbols, living water, the bread from heaven, the vine and branches, the Good Shepherd, and the temple body, translate the identity of Jesus and the life he imparts into tangible images.[72] These symbols interweave sacramental resonances with scriptural echoes, shaping a spirituality of abiding and mission for the Johannine communities.[2][5]

Revelation amplifies the dualism through cosmic pairs such as heaven and earth, the beast and the Lamb, Babylon and the New Jerusalem, or the harlot and the bride.[3] The imagery sustains pastoral exhortation by urging assemblies to resist imperial pressure, worship the enthroned Lamb, and hope for the descent of the holy city.[10][71]

Pneumatology

The Gospel promises another Paraclete, the Spirit of truth, whose functions span teaching, reminding, witnessing, guiding, and convicting.[37] In the Farewell Discourses the Paraclete teaches and recalls Jesus's words for the disciples (John 14:26), bears witness alongside them (15:26–27), guides into all truth and glorifies the Son (16:13–14), and convicts the world regarding sin, righteousness, and judgment (16:8–11).[67] The language portrays the Spirit as the continuing presence of Jesus that interprets revelation for the community and empowers its testimony.[75]

The Johannine Letters articulate this pneumatology through the language of anointing (χρῖσμα) that teaches believers from within (1 John 2:20, 27) and through the mandate to test the spirits (4:1–3).[8] Confession that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, coupled with practices of righteousness and love, becomes the criterion for discerning the Spirit of truth from the spirit of error, thus safeguarding the community against deceivers.[16][75]

Revelation presents the Spirit as the prophetic voice addressing each church with the repeated appeal, hear what the Spirit says to the churches (Revelation 2–3).[3] The visions culminate with the Spirit and the bride inviting the thirsty to come (22:17), underscoring the Spirit's role in sustaining worship, perseverance, and eschatological hope amid imperial pressure.[10][71]

Eschatology

The Gospel expresses realized eschatology in which eternal life is already present for those who believe, yet it balances this with future expectations.[76] Jesus's words about resurrection on the last day (John 6:39–54; 11:24–25) and his promise to return (14:3) keep a future horizon alongside the believer's present participation in life, judgment, and mission.[77][78]

Revelation advances a prophetic eschatology oriented to pastoral encouragement for first century assemblies. Its visions denounce imperial violence, call churches to endurance, and climax in the hope of a New Heaven and New Earth where God dwells with humanity (Revelation 21–22).[3] The imagery sustains worship and witness rather than supplying a predictive timetable.[10][79]

Ecclesiology

Johannine ecclesiology develops a communal identity that centers on abiding in Christ, keeping the new commandment to love one another, and remaining united in witness.[80] The Gospel portrays disciples as branches in the True Vine (John 15) and shapes leadership through service, foot washing, and shared testimony, suggesting a network of communities formed around relational loyalty rather than hierarchical control.[81][82]

John 21 depicts complementary roles as Peter receives a pastoral commission to tend the flock while the Beloved disciple embodies enduring witness.[80] The interplay models diverse forms of leadership that converge in sustaining the community's mission without erasing individual callings.[83]

The Letters employ boundary setting language to maintain communal integrity. 1 John links authentic fellowship to confessing the incarnate Son, practicing righteousness, and extending love, while 2 John and 3 John warn against deceivers and highlight tensions with leaders such as Diotrephes who refuse apostolic representatives.[8] These texts present discernment, hospitality, and discipline as essential to safeguarding unity.[16][17]

Revelation's messages to the seven assemblies offer case studies in local church life by combining affirmation, critique, and promises tailored to each civic context.[3] The Spirit's word diagnoses complacency, compromise, or endurance, exhorting believers in places such as Ephesus, Sardis, and Laodicea to renew love, resist idolatry, and hold fast amid pressure, thereby framing corporate faithfulness as an ongoing task.[71][84]

Remove ads

Modern scholarship and debates

Summarize

Perspective

Craig R. Koester's commentary and the Oxford Handbook of the Book of Revelation present Revelation as an apocalypse, prophetic book, and circular letter, and they identify a Domitianic date in the mid 90s as the prevailing position while noting alternative chronologies.[3][49] Essays in the Oxford Handbook of Johannine Studies treat the Gospel and Epistles as layered compositions that emerged from a Johannine network rather than a single author.[1]

Jörg Frey argues that the narrative is a theological construct shaped across multiple stages of composition, which leaves any earlier "signs source" conjectural.[85] William B. Bowes reexamines John's knowledge of the Synoptic Gospels and finds that assuming familiarity with Mark clarifies several overlaps and divergences.[86] Stan Harstine contrasts diachronic and synchronic approaches and treats the Prologue as a lens for reading the Gospel's rhetoric.[15]

Richard Bauckham links the Gospel's witness language to the figure of the Beloved disciple and treats it as evidence for historical reliability.[87] Craig S. Keener frames the canonical Gospels, including John, as ancient biographies whose memory practices could preserve reliable testimony.[88] Narrative scholars such as R. Alan Culpepper and essays in the Oxford Handbook of Johannine Studies read the witness theme as a theological device within a crafted narrative rather than verbatim reporting.[6][1]

Adele Reinhartz reads the language as a programmatic anti Judaism rather than a precise record of expulsions.[35] J. Andrew Doole reviews Second Temple and rabbinic evidence for the term "aposynagogos" and concludes that it does not document a uniform policy of exclusion.[34]

Alicia D. Myers reads 1 John as opposing christological error and deficient practice within a network aligned with the Gospel, contributing to ongoing debates about the identity of the secessionists addressed in the letter.[89] Judith Lieu emphasizes that the letters mark boundaries through confession and love without supplying a full portrait of the opponents.[8] Hugo Méndez, Elizabeth J. B. Corsar, and other contributors to a 2024 volume edited by Christopher W. Skinner and Christopher Seglenieks question whether the Johannine writings reflect a historical community at all and treat the opponents as literary constructs.[13][90][91][92]

Koester and contributors to the Oxford Handbook of the Book of Revelation present the work as an apocalypse addressed to seven assemblies in Roman Asia and favor a mid 90s setting under Domitian. Ian Paul makes the same case while integrating apocalyptic and epistolary features, whereas Jonathan Bernier restates proposals for composition under Nero in the late 60s.[49][3][93][94][12]

Martinus C. de Boer, Stan Harstine, and Craig R. Koester employ approaches from historical criticism, probing sources and provenance, to narrative and rhetorical analysis, as well as intertextual and social scientific frameworks — their works illustrate how applying these methods shapes distinct scholarly reconstructions of John's Gospel, the Epistles, and Revelation.[1][15][49]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads