Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Sorbs

West Slavic ethnic group From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sorbs (Upper Sorbian: Serbja; Lower Sorbian: Serby; German: Sorben pronounced [ˈzɔʁbn̩] ⓘ; Czech: Lužičtí Srbové; Polish: Serbołużyczanie; also known as Lusatians, Lusatian Serbs[5] and Wends) are an indigenous West Slavic ethnic group predominantly inhabiting the parts of Lusatia located in the German states of Saxony and Brandenburg. Sorbs traditionally speak the Sorbian languages (also known as "Wendish" and "Lusatian"), which are closely related to Czech and Lechitic languages. Upper Sorbian and Lower Sorbian are officially recognized minority languages in Germany.

In the Early Middle Ages, the Sorbs formed their own principality, which later shortly became part of the early West Slavic Samo's Empire and Great Moravia, as were ultimately conquered by the East Francia (Sorbian March) and Holy Roman Empire (Saxon Eastern March, Margravate of Meissen, March of Lusatia). From the High Middle Ages, they were ruled at various times by the closely related Poles and Czechs, as well as the more distant Germans and Hungarians. Due to a gradual and increasing assimilation between the 17th and 20th centuries, virtually all Sorbs also spoke German by the early 20th century. In the newly created German nation state of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, policies were implemented in an effort to Germanize the Sorbs. These policies reached their climax under the Nazi regime, who denied the existence of the Sorbs as a distinct Slavic people by referring to them as "Sorbian-speaking Germans". The community is divided religiously between Roman Catholicism (the majority) and Lutheranism. The former Minister President of Saxony Stanislaw Tillich is of Sorbian origin.

Remove ads

Etymology

The ethnonym "Sorbs" (Serbja, Serby) derives from the medieval ethnic groups called "Sorbs" (Surbi, Sorabi). The original ethnonym, Srbi, was retained by the Sorbs and Serbs in the Balkans.[6] By the 6th century, Slavs occupied the area west of the Oder formerly inhabited by Germanic peoples.[6] The Sorbs are first mentioned in the 6th or 7th century. In their languages, the other Slavs call them the "Lusatian Serbs", and the Sorbs call the Serbs "the south Sorbs".[7] The name "Lusatia" was originally applied only to Lower Lusatia.[6] It is generally considered that their ethnonym *Sŕbъ (plur. *Sŕby) originates from Proto-Slavic with an appellative meaning of a "family kinship" and "alliance", however others argue a derivation from Iranian-Sarmatian.[8][9][10][11]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Early Middle Ages

The name of the Sorbs can be traced to the 6th century or earlier when Vibius Sequester recorded Cervetiis living on the other part of the river Elbe which divided them from the Suevi (Albis Germaniae Suevos a Cerveciis dividiit).[12][13][14][15][16] According to Lubor Niederle, the Serbian district was located somewhere between Magdeburg and Lusatia, and was later mentioned by the Ottonians as Ciervisti, Zerbisti and Kirvisti.[17] The information is in accordance with the Frankish 7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar according to which the Surbi lived in the Saale-Elbe valley, having settled in the Thuringian part of Francia since the second half of the 6th century or beginning of the 7th century and were vassals of the Merovingian dynasty.[12][18][19]

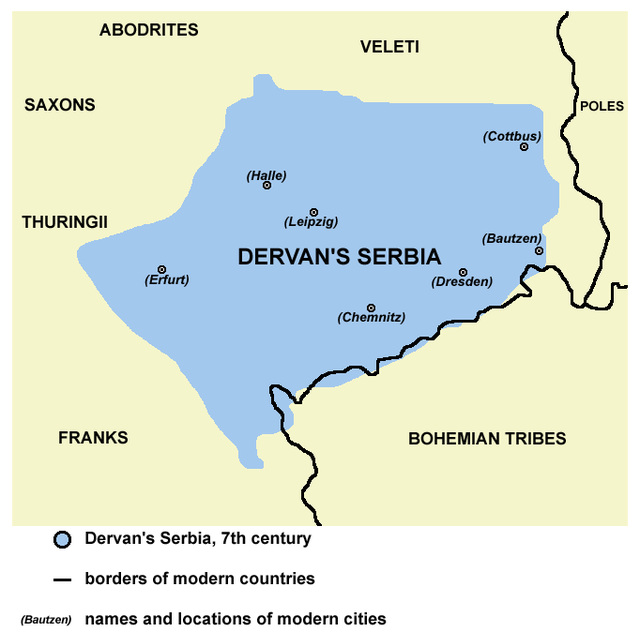

The Saale-Elbe line marked the approximate limit of Slavic westward migration.[20] Under the leadership of dux (duke) Dervan ("Dervanus dux gente Surbiorum que ex genere Sclavinorum"), they joined the Slavic tribal union of Samo, after Samo's decisive victory against Frankish King Dagobert I in 631.[18][19] Afterwards, these Slavic tribes continuously raided Thuringia.[18] The fate of the tribes after Samo's death and dissolution of the union in 658 is undetermined, but it is considered that they subsequently returned to Frankish vassalage.[21]

According to a 10th-century source De Administrando Imperio, they lived "since the beginning" in the region called by them as Boiki which was a neighbor to Francia, and when two brothers succeeded their father, one of them migrated with half of the people to the Balkans during the rule of Heraclius in the first half of the 7th century.[22][23] According to some scholars, the unnamed 7th-century Serbian ruler who led the White Serbs to the Balkans was most likely a son, brother or other relative of Dervan.[24][25][26][27]

Sorbian tribes, Sorbi/Surbi, are noted in the mid-9th-century work of the Bavarian Geographer.[8][28][29] Having settled by the Elbe, Saale, Spree, and Neisse in the 6th and early 7th century, Sorbian tribes divided into two main groups, which have taken their names from the characteristics of the area where they had settled. The two groups were separated from each other by a wide and uninhabited forest range, one around Upper Spree and the rest between the Elbe and Saale.[30] Some scholars consider that the contemporary Sorbs are descendants of the two largest Sorbian tribes, the Milceni (Upper) and Lusici [de] (Lower), and these tribes' respective dialects have developed into separate languages.[6][31] However, others emphasize differences between these two dialects and that their respective territories correspond to two different Slavic archeological cultures of Leipzig group (Upper Sorbian language) and Tornow group ceramics (Lower Sorbian language),[30] both a derivation of Prague(-Korchak) culture.[32][33]

The Annales Regni Francorum state that in 806, Sorbian Duke Miliduch fought against the Franks and was killed. In 840, Sorbian Duke Czimislav was killed. From the 9th century was organized Sorbian March by the East Francia and from the 10th century the Saxon Eastern March (Margravate of Meissen) and March of Lusatia by the Holy Roman Empire. In 932, the German king Henry I conquered Lusatia and Milsko. Gero, Margrave of the Saxon Eastern March, reconquered Lusatia the following year and, in 939, murdered 30 Sorbian princes during a feast.[34] As a result, there were many Sorbian uprisings against German rule. A reconstructed castle, at Raddusch in Lower Lusatia, is the sole physical remnant from this early period.

High and Late Middle Ages

In 1002, the Sorbs came under the rule of their Slavic relatives, the Poles, when Bolesław I of Poland took over Lusatia. Following the subsequent German–Polish War of 1003–1018, the Peace of Bautzen confirmed Lusatia as part of Poland; but, it returned to German rule in 1031. In the 1070s, southern Lusatia, passed into the hands of the Sorbs' other Slavic relatives, the Czechs, within their Duchy of Bohemia. There was a dense network of dynastic and diplomatic relations between German and Slavic feudal lords, e.g. Wiprecht of Groitzsch (a German) rose to power through close links with the Bohemian (Czech) king and marriage to the king's daughter.[citation needed]

The Kingdom of Bohemia eventually became a politically influential member of the Holy Roman Empire, but was in a constant power-struggle with neighbouring Poland. In the following centuries, at various times, parts of Lusatia passed to Piast-ruled fragmented Poland. In the German-ruled parts, Sorbs were ousted from guilds, the Sorbian language was banned and German colonisation and Germanisation policies were enacted.[35]

From the 11th to the 15th century, agriculture in Lusatia developed and colonization by Frankish, Flemish and Saxon settlers intensified. This can still be seen today from the names of local villages which geographically form a patchwork of typical German (ending on -dorf, -thal etc.) and typical Slavic origin (ending on -witz, -ow etc.), indicating the language originally spoken by its inhabitants, although some of the present German names may be of later origin from the time of planned name changes to erase Slavic origin, especially in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1327 the first prohibitions on using Sorbian before courts and in administrative affairs in the cities of Altenburg, Zwickau and Leipzig appeared. Speaking Sorbian in family and business contexts was, however, not banned, as it did not involve the functioning of the administration. Also the village communities and the village administration usually kept operating in Sorbian.

Early modern period

From 1376 to 1469 and from 1490 to 1635 Lusatia was part of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown under the rule of the houses of Luxembourg, Jagiellon and Habsburg and other kings, whereas from 1469 to 1490 it was ruled by King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. Under Bohemian (Czech) rule, Sorbs were allowed to return to cities, offices and crafts, Germanisation significantly reduced and the Sorbian language could be used in public.[36] From the beginning of the 16th century the whole Sorbian-inhabited area, with the exception of Bohemian-ruled Lusatia, underwent Germanization.

During the Thirty Years' War, in 1635, Lusatia became a fiefdom of Saxon electors, but it retained a considerable autonomy and largely its own legal system (see Lusatian League). The Thirty Years' War and the plague of the 17th century caused terrible devastation in Lusatia. This led to further German colonization and Germanization.

In 1667 the Prince of Brandenburg, Frederick Wilhelm, ordered the immediate destruction of all Sorbian printed materials and banned saying masses in this language. At the same time, the Evangelical Church supported printing Sorbian religious literature, as a means of fighting the Counterreformation. With the formation of the Polish-Saxon union in 1697, Polish-Sorbian contacts resumed, and Poles influenced the Sorbs' national and cultural activities (see Relationship with Poland below). With the Age of Enlightenment, the Sorbian national revival began and resistance to Germanization emerged.[37] In 1706 the Sorbian Seminary, the main centre for the education of Sorbian Catholic priests, was founded in Prague.[37] Sorbian preaching societies were founded by Evangelical students in Leipzig and Wittenberg in 1716 and 1749, respectively.[37]

Late modern period

The Congress of Vienna, in 1815, divided Lusatia between Prussia and Saxony. More and more bans on the use of Sorbian languages appeared from then until 1835 in Prussia and Saxony; emigration of the Sorbs, mainly to the town of Serbin in Texas and to Australia, increased. In 1848, 5,000 Sorbs signed a petition to the Saxon Government, in which they demanded equality for the Sorbian language with the German one in churches, courts, schools and Government departments. From 1871, the whole of Lusatia became a part of united Germany and was divided between two parts; Prussia (Silesia and Brandenburg), and Saxony.

In 1871, the industrialization of the region and German immigration began; official Germanization intensified. Persecution of the Sorbs under German rule became increasingly harsh throughout the 19th century. Slavs were labeled inferior to Germanic peoples, and in 1875, the use of Sorbian was banned in German schools. As a result, almost the entire Sorbian population was bilingual by the end of the 19th century.[a]

During World War I, one of the most venerated Serbian generals was Pavle Jurišić Šturm (Paul Sturm), a Sorb from Görlitz, Province of Silesia.[citation needed]

Interbellum and World War II

Although the Weimar Republic guaranteed constitutional minority rights, it did not practice them.[39]

Under Nazi Germany, Sorbians were described as a German tribe who spoke a Slavic language. Sorbian costume, culture, customs, and the language was said to be no indication of a non-German origin. The Reich declared that there were truly no "Sorbs" or "Lusatians", only Wendish-speaking Germans. As such, while the Sorbs were largely safe from the Reich's policies of ethnic cleansing, the cultivation of "Wendish" customs and traditions was to be encouraged in a controlled manner and it was expected that the Slavic language would decline due to natural causes. Young Sorbs enlisted in the Wehrmacht and were sent to the front. The entangled lives of the Sorbs during World War II are exemplified by the life stories of Mina Witkojc, Měrćin Nowak-Njechorński and Jan Skala.

Persecution of the Sorbs reached its climax under the Nazis, who attempted to completely assimilate and Germanize them. Their distinct identity and culture and Slavic origins were denied by referring to them as "Wendish-speaking Germans". Under Nazi rule, the Sorbian language and practice of Sorbian culture was banned, Sorbian and Slavic place-names were changed to German ones,[40] Sorbian books and printing presses were destroyed, Sorbian organizations and newspapers were banned, Sorbian libraries and archives were closed, and Sorbian teachers and clerics were deported to German-speaking areas and replaced with German-speaking teachers and clerics. Leading figures in the Sorbian community were forcibly isolated from their community or simply arrested.[b][c][d][e][f] The Sorbian national anthem and flag were banned.[46] The specific Wendenabteilung was established to monitor the assimilation of the Sorbs.[a]

Towards the end of World War II, the Nazis considered the deportation of the entire Sorbian population to the mining districts of Alsace-Lorraine.[b][d]

East Germany

The first Lusatian cities were captured in April 1945, when the Red Army and the Polish Second Army crossed the river Queis (Kwisa). The defeat of Nazi Germany changed the Sorbs’ situation considerably. The regions in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic) faced heavy industrialisation and a large influx of expelled Germans.[citation needed] The East German authorities tried to counteract this development by creating a broad range of Sorbian institutions. The Sorbs were officially recognized as an ethnic minority, more than 100 Sorbian schools and several academic institutions were founded, the Domowina and its associated societies were re-established and a Sorbian theatre was created. Owing to the suppression of the church and forced collectivization, however, these efforts were severely affected and consequently over time the number of people speaking Sorbian languages decreased by half.

The relationship between the Sorbs and the government of East Germany was not without occasional difficulties, mainly because of the high levels of religious observance and resistance to the nationalisation of agriculture. During the compulsory collectivization campaign, a great many unprecedented incidents were reported. Thus, throughout the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, violent clashes with the police were reported in Lusatia. A small uprising took place in three upper communes of Błot. There were also tensions between German and Sorbian parents in the 1950s and early 1960s, as many German families protested the state policy of mandatory instruction of the Sorbian language in schools located in bilingual areas. As a consequence of the tensions, which split the local SED, Sorbian language classes were no longer mandatory after 1964, and a temporary but sharp decline in the number of learners occurred immediately thereafter. The number of learners increased again after 1968, when new regulations were adopted giving Domowina a greater role in consulting parents of schoolchildren. The number of learners did not decrease again until after German reunification.[47]

Sorbs experienced greater representation in the German Democratic Republic than under any other German government. Domowina had status as a constituent member organization of the National Front, and a number of Sorbs were members of the Volkskammer and State Council of East Germany. Notable Sorbian figures of the period include Domowina Chairmen Jurij Grós and Kurt Krjeńc, State Council member Maria Schneider, and writer and three-time recipient of the National Prize of the German Democratic Republic Jurij Brězan.[48]

In 1973, Domowina reported that 2,130 municipal councillors, 119 burgomasters, and more than 3,500 members of commissions and local bodies in East Germany were ethnic Sorbs registered with the organization.[49] Additionally, there was a seat reserved for a Sorbian representative in the Central Council of the Free German Youth, the mass organization for young people in East Germany, and magazines for both the FDJ and the Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation were published in the Sorbian language on a regular basis under the titles Chorhoj Měra and Plomjo, respectively.[50] As of 1989, there were nine schools with exclusively Sorbian language instruction, eighty-five schools that offered Sorbian-language instruction, ten Sorbian-language periodicals, and one daily newspaper.[51]

After reunification

After the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, Lusatians made efforts to create an autonomous administrative unit; however, Helmut Kohl’s government did not agree to it.[citation needed] After 1989, the Sorbian movement revived, however, it still encounters many obstacles. Although Germany supports national minorities, Sorbs claim that their aspirations are not sufficiently fulfilled.[citation needed] The desire to unite Lusatia in one of the federal states has not been taken into consideration. Upper Lusatia still belongs to Saxony and Lower Lusatia to Brandenburg. Liquidations of Sorbian schools, even in areas mostly populated by Sorbs, still happen, under the pretext of financial difficulties or demolition of whole villages to create lignite quarries.[citation needed]

Faced with growing threat of cultural extinction, the Domowina issued a memorandum in March 2008[52] and called for "help and protection against the growing threat of their cultural extinction, since an ongoing conflict between the German government, Saxony and Brandenburg about the financial distribution of help blocks the financing of almost all Sorbian institutions". The memorandum also demands a reorganisation of competence by ceding responsibility from the Länder to the federal government and an expanded legal status. The call has been issued to all governments and heads of state of the European Union.[53]

Dawid Statnik, president of Domowina, the umbrella association of Sorbs in Germany, said in an interview with Tagesspiegel that he considers it dangerous that the AFD defines the issue of German citizens through an ethnic aspect. He believes that there is a concrete danger for the Sorbs if the AfD enters the governments of the federal states of Brandenburg and Saxony in the autumn elections.[54] From 2008 to 2017, Stanislaw Tillich, a Catholic Sorb, served as the Minister-President of Saxony – the first time a Sorb held this office. Since 2014, various sources have pointed to a rising number of right-wing extremist attacks against Sorbs.[55]

Remove ads

Population genetics

Summarize

Perspective

According to 2013 and 2015 studies, the most common Y-DNA haplogroup among the Sorbs who speak Upper Sorbian in Lusatia (n=123) is R1a with 65%, mainly its R-M458 subclade (57%). It is followed in frequency by I1 (9.8%), R1b (9.8%), E1b1b (4.9%), I2 (4.1%), J (3.3%) and G (2.4%). Other haplogroups are less than 1%.[56][57] A study from 2003 reported a similar frequency of 63.4% of haplogroup R1a among Sorbian males (n=112).[58] Other studies that covered aspects of Sorbian Y-DNA include Immel et al. 2006,[59] Rodig et al. 2007,[60] and Krawczak et al. 2008.[61] Significant percentage of R1a (25.7-38.3%), but strongly diminished in value because of high R1b (33.5-21.7%), and low I2 (5.8-5.1%) are in whole Saxony and Germania Slavica area as well.[62]

A 2011 paper on the Sorbs' autosomal DNA reported that the Upper Sorbian speakers (n=289) showed the greatest autosomal genetic similarity to Poles, followed by Czechs and Slovaks, consistent with the linguistic proximity of Sorbian to other West Slavic languages.[63] In another genome-wide paper from the same year on Upper Sorbs (n=977), which indicated their genetic isolation "which cannot be explained by over-sampling of relatives" and a closer proximity to Poles and Czechs than Germans. The researchers however question this proximity, as the German reference population was almost exclusively West-German, and the Polish and Czech reference population had many that were part of a German minority.[64] In a 2016 paper, Sorbs cluster autosomally again with Poles (from Poznań).[65]

Language and culture

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

The oldest known relic of Sorbian literature originated in about 1530 – the Bautzen townsmen's oath. In 1548, Mikołaj Jakubica – Lower Sorbian vicar, from the village called Lubanice, wrote the first unprinted translation of the New Testament into Lower Sorbian. In 1574 the first Sorbian book was printed: Albin Mollers’ songbook. In 1688 Jurij Hawštyn Swětlik translated the Bible for Catholic Sorbs. From 1706 to 1709, the New Testament was printed in the Upper Sorbian translation was done by Michał Frencel and in Lower Sorbian by Jan Bogumił Fabricius (1681–1741). Jan Bjedrich Fryco (a.k.a. Johann Friedrich Fritze) [1747–1819], translated the Old Testament for the first time into Lower Sorbian, published in 1790.

Prominent 19th-century Sorbian writers, from top left to right: Handrij Zejler, Jan Arnošt Smoler, Mato Kósyk, Jakub Bart-Ćišinski

Other Sorbian Bible translators include Jakub Buk (1825–1895), Michał Hórnik (Michael Hornig) [1833–1894], Jurij Łušćanski (a.k.a. Georg Wuschanski) [1839–1905]. In 1809 for the short period of time, there was the first printed Sorbian newspaper. In 1767 Jurij Mjeń publishes the first secular Sorbian book. Between 1841 and 1843, Jan Arnošt Smoler and Leopold Haupt (a.k.a. J.L. Haupt and J.E. Schmaler) published two-volume collection of Wendish folk-songs in Upper and Lower Lusatia. From 1842, the first Sorbian publishing companies started to appear: the poet Handrij Zejler set up a weekly magazine, the precursor of today’s Sorbian News. In 1845 in Bautzen, the first festival of Sorbian songs took place. In 1875, Jakub Bart-Ćišinski, the poet and classicist of Upper Sorbian literature, and Karol Arnošt Muka created a movement of young Sorbians influencing Lusatian art, science and literature for the following 50 years. A similar movement in Lower Lusatia was organized around the most prominent Lower Lusatian poets Mato Kósyk (Mato Kosyk) and Bogumił Šwjela.

In 1904, mainly thanks to the Sorbs’ contribution, the most important Sorbian cultural centre (the Sorbian House) was built in Bautzen. In 1912, the social and cultural organization of Lusatian Sorbs was created, the Domowina Institution – the union of Sorbian organizations. In 1919, it had 180,000 members. In 1920, Jan Skala set up a Sorbian party and in 1925 in Berlin, Skala started Kulturwille – the newspaper for the protection of national minorities in Germany. In 1920, the Sokol Movement was founded (youth movement and gymnastic organization). From 1933, the Nazi party started to repress the Sorbs. At that time the Nazis also dissolved the Sokol Movement and began to combat every sign of Sorbian culture. In 1937, the activities of the Domowina Institution and other organizations were banned as anti-national. Sorbian clergymen and teachers were forcedly deported from Lusatia; Nazi German authorities confiscated the Sorbian House, other buildings and crops.

On May 10, 1945, in Crostwitz, after the Red Army's invasion, the Domowina Institution renewed its activity. In 1948, the Landtag of Saxony passed an Act guaranteeing protection to Sorbian Lusatians; in 1949, Brandenburg resolved a similar law. Article 40 of the constitution of German Democratic Republic adopted on 7 October 1949 expressly provided for the protection of the language and culture of the Sorbs. In the times of the German Democratic Republic, Sorbian organizations were financially supported by the country, but at the same time the authorities encouraged Germanization of Sorbian youth as a means of incorporating them into the system of "building Socialism". Sorbian language and culture could only be publicly presented as long as they promoted socialist ideology. For over 1,000 years, the Sorbs were able to maintain and even develop their national culture, despite escalating Germanization and Polonization, mainly due to the high level of religious observance, cultivation of their tradition and strong families (Sorbian families still often have five children). In the middle of the 20th century, the revival of the Central European nations included some Sorbs, who became strong enough to attempt twice to regain their independence. After World War II, the Lusatian National Committee in Prague claimed the right to self-government and separation from Germany and the creation of a Lusatian Free State or attachment to Czechoslovakia. The majority of the Sorbs were organized in the Domowina, though, and did not wish to split from Germany.[citation needed] Claims asserted by the Lusatian National movement were postulates of joining Lusatia to Poland or Czechoslovakia. Between 1945 and 1947 they postulated about ten petitions[66] to the United Nations, the United States, Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, Poland and Czechoslovakia, however, it did not bring any results. On April 30, 1946, the Lusatian National Committee also postulated a petition to the Polish Government, signed by Pawoł Cyž – the minister and an official Sorbian delegate in Poland. There was also a project of proclaiming a Lusatian Free State, whose Prime Minister was supposed to be a Polish archaeologist of Lusatian origin- Wojciech Kóčka. The most radical postulates in this area ("Na swobodu so ńečeka, swobodu so beŕe !")[67] were expressed by the Lusatian youth organization- Narodny Partyzan Łužica. Similarly, in Czechoslovakia, where before the Potsdam Conference in Prague, 300,000 people demonstrated for the independence of Lusatia. The endeavours to separate Lusatia from Germany did not succeed because of various individual and geopolitical interests.

The following statistics indicate the progression of cultural change among Sorbs: by the end of the 19th century, about 150,000 people spoke Sorbian languages. By 1920, almost all Sorbs had mastered Sorbian and German to the same degree. Nowadays, the number of people using Sorbian languages has been estimated to be no more than 40,000. A 2024 study estimates the number of Lower Sorbian speakers at a competent level to be between 50 and 100.[68]

The Israeli Slavic linguist Paul Wexler has argued that the Yiddish language structure provides "compelling evidence of an intimate Jewish contact with the Slavs in the German and Bohemian lands as early as the 9th century", and has theorized that Sorbs may have been contributors to the Ashkenazic Jewish population in Europe from the same period.[69][70]

Fine arts

Traditions

Many traditions have been preserved, especially Easter horseback riding, the Bird Wedding, and the traditional painting of Easter eggs. Numerous Slavic mythological beliefs are still alive today, such as the Midday Woman (Připołdnica / Přezpołdnica), the Water Man (Wódny muž), the Divine Lament (Bože sadleško), or the money- and luck-bringing dragon (Upper Sorbian: zmij, Lower Sorbian: plón).

In the Upper Sorbian core area, roughly defined by a triangle between the towns of Bautzen, Kamenz, and Wittichenau, wayside crucifixes and those in front gardens, along wit h well-kept churches and chapels, are expressions of a (mostly Catholic) popular piety still practiced today, which has contributed significantly to preserving Sorbian identity.[citation needed]

Sorbian folk costumes vary greatly by region. Some older women still wear them daily, while younger women usually only wear them on major feast days, such as the Corpus Christi (Fronleichnam) celebration, when the bridesmaid's costume (družka) is worn.[citation needed]

A Shrove Tuesday festival Zapust is the most popular tradition of the Sorbs, deeply linked to the working life of the community. Traditionally, festivities would last one week ahead of the spring sowing of the fields and would feature traditional dress, parade and dancing.[71]

Egg decorating (pisanici) is a Slavic Easter tradition maintained by Sorbs since the 17th century.[72][better source needed]

Religion

Most current speakers of Upper-Sorbian are part of the Catholic denomination. Originally, the majority of Sorbs were Lutheran Protestants, and this was still the case going into the 20th Century (with a Protestant population of 86.9% recorded in 1900).[73] Only the Sorbs of the Kamenz area – predominantly settled on the expansive former site of the Saint Marienstern Monastery in Panschwitz-Kuckau – veered from the norm, with a Catholic population of 88.4%. Otherwise, the proportion of Catholics remained under 1% throughout the region of Lower Lusatia. Due to the rapid decline in language and cultural identity amongst the Protestant Sorbs – particularly during the years of the GDR – the denominational make-up of the Sorbian-speaking population of the region has now been reversed.[citation needed]

The differing development of language use among Catholic and Protestant Sorbs is partly due to the differing structures of the churches. While the Protestant Church is a state church (and the rulers of Sorbian territories were always German-speaking), the Catholic Church, with its ultramontane orientation toward the Vatican, has always been transnational.The Protestant Church’s closer ties to the state had a particularly negative effect on the Sorbian language area, especially in Lower Lusatia, where a policy of Germanization had been pursued since the 17th century.

On the other hand, the Catholic Church generally held the view that one’s native language is a gift from God, and that abandoning it would be sinful. This explains the increasingly emphasized close connection between Catholicism and Sorbian identity since the late 19th century—an association that still exists today.

Today, Catholic communities form the core of the remaining Sorbian majority areas, whereas in the Protestant regions in the east and north, the language has mostly disappeared. In western Upper Lusatia, it was especially the centuries-long bond between the Sorbs and the Catholic Church that played a decisive role in preserving the Sorbian mother tongue. In contrast, in Lower Lusatia, the Protestant Church, both before and after 1945—and despite the general promotion of the Sorbs in the GDR—showed no interest in maintaining the Sorbian language in religious life. Only since 1987, at the initiative of a few Lower Sorbs, have regular Wendish-language church services resumed.

Since the second half of the 20th century, there has also been a significant proportion of non-religious Sorbs.

Remove ads

National symbols

The flag of the Lusatian Sorbs is a cloth of blue, red and white horizontal stripes. First used as a national symbol in 1842, the flag was fully recognized among Sorbs following the proclamation of pan-Slavic colors at the Prague Slavic Congress of 1848. Section 25 of the Constitution of Brandenburg contains a provision on the Lusatian flag. Section 2 of the Constitution of Saxony contains a provision on the use of the coat of arms and traditional national colors of the Lusatian Sorbs. The laws on the rights of the Lusatian Sorbs of Brandenburg and Saxony contain provisions on the use of Lusatian national symbols (coat of arms and national colors).[74]

The national anthem of Lusatian Sorbs since the 20th century is the song Rjana Łužica (Beautiful Lusatia).[75] Previously, the songs “Still Sorbs Have Not Perished” (written by Handrij Zejler in 1840)[76] and “Our Sorbs Rise from the Dust” (written by M. Domashka, performed until 1945)[77] served as a hymn.

Remove ads

Regions of Lusatia

Summarize

Perspective

There are three main regions of Lusatia that differ in language, religion, and customs.

Region of Upper Lusatia

Flag and coat of arms of Upper Lusatia

Catholic Lusatia encompasses 85 towns in the districts of Bautzen, Kamenz, and Hoyerswerda, where Upper Sorbian language, customs, and tradition are still thriving. In some of these places (e.g., Radibor or Radwor in Sorbian, Crostwitz or Chrósćicy, and Rosenthal or Róžant), Sorbs constitute the majority of the population, and children grow up speaking Sorbian.

On Sundays, during holidays, and at weddings, people wear regional costumes, rich in decoration and embroidery, encrusted with pearls.

Some of the customs and traditions observed include Bird Wedding (25 January), Easter Cavalcade of Riders, Witch Burning (30 April), Maik, singing on St. Martin's Day (Nicolay), and the celebrations of Saint Barbara’s Day and Saint Nicholas’s Day.

Region of Hoyerswerda (Wojerecy) and Schleife (Slepo)

In the area from Hoyerswerda to Schleife, a dialect of Sorbian which combines characteristic features of both Upper and Lower Sorbian is spoken. The region is predominantly Protestant, highly devastated by the brown coal mining industry, sparsely populated, and to a great extent germanicized. Most speakers of Sorbian are over 60 years old.

The region distinguishes itself through many examples of Slavic wooden architecture monuments including churches and regular houses, a diversity of regional costumes (mainly worn by elderly women) that feature white-knitting with black, cross-like embroidery, and a tradition of playing bagpipes. In several villages, residents uphold traditional festivities such as expelling of winter, Maik, Easter and Great Friday singing, and the celebration of dźěćetko (disguised child or young girl giving Christmas presents).

Region of Lower Lusatia

Flag and coat of arms of Lower Lusatia

There are 60 towns from the area of Cottbus belonging to this region, where most of the older people over 60, but few young people and children can speak the Lower Sorbian language[citation needed]; the local variant often incorporates many words taken from the German language, and in conversations with the younger generation, German is generally preferred. Some primary schools in the region teach bilingually, and in Cottbus there is an important Gymnasium whose main medium of instruction is Lower Sorbian. The region is predominantly Protestant, again highly devastated by the brown coal mining industry. The biggest tourist attraction of the region and in the whole Lusatia are the marshlands, with many Spreewald/Błóta canals, picturesque broads of the Spree.

Worn mainly by older but on holidays by young women, regional costumes are colourful, including a large headscarf called "lapa", rich in golden embroidering and differing from village to village.

In some villages, following traditions are observed: Shrovetide, Maik, Easter bonfires, Roosters catching/hunting. In Jänschwalde (Sorbian: Janšojce) so-called Janšojski bog (disguised young girl) gives Christmas presents.

Remove ads

Relations with other Slavic nations

Summarize

Perspective

Relations with Poland

Medieval period

Bolesław I the Brave had taken control of the marches of Lusatia (Łużyce), Sorbian Meissen (Miśnia), and the cities of Budziszyn (Bautzen) and Miśnia in 1002, and refused to pay the tribute to the Empire from the conquered territories. The Sorbs sided with the Poles, and opened the town gates and allowed Bolesław I into Miśnia in 1002.[78] Bolesław, after the Polish-German War (1002–1018), signed the Peace of Bautzen on 30 January 1018, which made him a clear winner. The Polish ruler was able to keep the contested marches of Lusatia and Milsko not as fiefs, but as part of Polish territory.[79][80] The Polish prince Mieszko destroyed about 100 Sorbian villages in 1030 and expelled Sorbians from urban areas, with the exception of fishermen and carpenters who were allowed to live in the outskirts.[81] In 1075–1076, Polish King Bolesław II the Bold sought the restoration of Lusatia from Bohemia to Poland.[82] In the following centuries, at various times, parts of Lusatia formed part of Piast-ruled fragmented Poland.

18th century

The 18th century saw increased Polish-Sorbian contacts during the reign of Kings Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland in Poland and Lusatia. Sorbian pastor Michał Frencel [dsb] and his son polymath Abraham Frencel [hsb] took their cues from Polish texts in their Sorbian Bible translations and philological works, respectively.[83] Also Polish-born Jan Bogumił Fabricius established a Sorbian printing house and translated the catechism and New Testament into Sorbian.[84] Polish and Sorbian students established contacts at the University of Leipzig.[83] Polish dignitaries traveled through Lusatia on several occasions on their way between Dresden and Warsaw, encountering Sorbs.[85] Some Polish nobles owned estates in Lusatia.[85]

The first translation from Sorbian into another language was a translation of the poem Wottendzenje wot Liepska teho derje dostoineho wulze wuczeneho Knesa Jana Friedricha Mitschka by Handrij Ruška [hsb] into Polish, made by Stanisław Nałęcz Moszczyński, a Polish lecturer at the University of Leipzig, and published by the famous Polish traveler Jan Potocki.[87]

A distinct remnant of the region's ties to Poland are the 18th-century mileposts decorated with the coat of arms of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth located in various towns in the region.

19th century

Polish-Sorbian contacts continued in the 19th century. Noted advocate for the preservation of Polish culture and language in Masuria, Gustaw Gizewiusz, during his visits in Budissin and Leipzig, came into close contact with Sorbian publicist Jan Pětr Jordan [hsb], and then Jordan published a study on the situation of the Poles in Masuria, including a collection of documents and journal articles from 1834–1842.[88] In the 1840s, Polish Romantic poet Roman Zmorski [pl] befriended the Sorbian writer Jan Arnošt Smoler in Wrocław, and then he settled in Lusatia, where he got to know other leading Sorbian national revival figures Křesćan Bohuwěr Pful [hsb], Jaroměr Hendrich Imiš and Michał Hórnik [hsb].[89] Zmorski then issued the Polish newspaper Stadło in Budissin, translated four Smoler's poems into Polish, and published articles about the Sorbs in other Polish press.[90] Michał Hórnik declared his sympathy and admiration for the Poles, popularised knowledge of Nicolaus Copernicus and Tadeusz Kościuszko through Sorbian press, reported on the events of the Polish January Uprising of 1863–1864 and made contacts with Poles during visits to Warsaw, Kraków and Poznań.[91] Polish historian Wilhelm Bogusławski [pl] wrote the first book on Sorbian history Rys dziejów serbołużyckich, published in Saint Petersburg in 1861. The book was expanded and published again in cooperation with Michał Hórnik in 1884 in Bautzen, under a new title Historije serbskeho naroda. Polish historian and activist Alfons Parczewski [pl] was another friend of Sorbs, who from 1875 was involved in Sorbs' rights protection, participating in Sorbian meetings in Bautzen. Parczewski joined the Maćica Serbska organization in 1875, supported Sorbian publishing, wrote articles about Sorbs in Polish press and collected Sorbian magazines and books, which now form part of the Adam Asnyk Regional Public Library in Kalisz.[92] It was thanks to him, among others, that Józef Ignacy Kraszewski founded a scholarship for Sorbian students. His sister Melania Parczewska [pl] joined the Maćica Serbska in 1878, wrote articles about Sorbs in Polish press and translated Sorbian poems into Polish.[92]

Early 20th century

In the early 20th century, Polish slavist and professor Henryk Ułaszyn [pl] met several prominent Sorbs, including Jan Skala, Jakub Bart-Ćišinski and Arnošt Muka.[94]

After World War I and the restoration of independent Poland, Polish linguist Jan Baudouin de Courtenay supported the Sorbs' right to self-determination and demanded that the League of Nations assume protection over them.[95] In the interbellum, the Poles and Sorbs in Germany closely cooperated as part of the Association of National Minorities in Germany, established at the initiative of the Union of Poles in Germany in 1924. Sorbian journalist, poet and activist Jan Skala was a member of the press headquarters of the Union of Poles in Germany, and was one of the authors of the Leksykon Polactwa w Niemczech ("Lexicon of Poles in Germany").[96] In 1935–1936, Sorb Jurij Cyž was employed as a legal advisor of the First District of the Union of Poles in Germany, before he left for Poland under pressure of the Nazi authorities of Germany.[97] There were also notable Polish communities in Lusatia, such as Klettwitz (Upper Sorbian: Klěśišća, Polish: Kletwice).[93]

In Poland, Antoni Ludwiczak, founder of the folk high school in Dalki, Gniezno, offered Sorbs five tuition-free spots for each course at the school, however, after the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, enrollment of Sorbs in the school was almost completely halted.[98] Several Sorbs studied in Poland in the interbellum.[99] In 1930, the Association of Friends of the Sorbs was established in Poznań with Henryk Ułaszyn as its president.[100] Similar associations, the Polish Association of Friends of the Sorbian Nation (Polskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Narodu Łużyckiego) at the University of Warsaw and the Association of Friends of Lusatia (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Łużyc) in Katowice were established in 1936.[97] The Warsaw-based organization gathered people not only from the university. Its president was Professor Stanisław Słoński, and the deputy president was Julia Wieleżyńska. The association was a legal entity. The association in Warsaw issued the Polish-language Biuletyn Serbo-Łużycki ("Sorbian Newsletter"), which reported on Serbian affairs. The association in Katowice was led by Karol Grzesik, who was murdered by the Russians in the Katyn massacre during World War II.[101][102]

During World War II, the Poles postulated that after the defeat of Germany, the Sorbs should be allowed free national development either within the borders of Poland or Czechoslovakia, or as an independent Sorbian state in alliance with Poland.[103] On 22 January 1945, Jan Skala was murdered by a Soviet soldier in Dziedzice, and his grave at the local cemetery is now a Polish protected cultural heritage monument.[104] There is also a memorial to Skala in nearby Namysłów. In 1945, Polish troops fought against German forces in several battles in Lusatia, including the largest Battle of Bautzen. There are memorials to Polish soldiers in Bautzen (Budyšin), Crostwitz (Chrósćicy) and Königswartha (Rakecy) with inscriptions in Sorbian, Polish and German.

After 1945, the Sorbs that historically lived in the eastern part of Lusatia (now again part of Poland) were expelled, as they were German citizens. Eastern Lusatia was resettled by Poles expelled from former eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union and has by now lost its Sorbian identity.[105]

After World War II

Prołuż founded in Krotoszyn, expanded to all Poland (3,000 members). It was the biggest non-communist organization that dealt with foreign affairs. This youth organization was created during the Soviet occupation and its motto was "Polish guard over Lusatia" (Polish: Nad Łużycami polska straż). Its highest activity was in the region of Greater Poland. After the creation of East Germany, Prołuż was dissolved, and its president historian from Poznań Alojzy Stanisław Matyniak was arrested.[106]

In 1946, the establishment of a gymnasium for Sorbs in Zgorzelec, Poland, was initiated, and the registration of Sorbian students at Polish universities resumed.[107] Despite the readiness to accept Sorbian youth in 1946, the gymnasium was not opened as the Sorbs had not yet obtained border passes to Poland.[108] The launch of the gymnasium was postponed by a year and free boarding and scholarships were prepared for the Sorbs, but in view of the continued lack of border passes to Poland and the establishment of a Sorbian gymnasium in Bautzen, the idea was abandoned.[109]

One of the main centers of pro-Sorbian initiatives in post-war Poland was Wrocław, with a branch of the Prołuż organization, and several articles about the Sorbs were published in local press.[110] In 1946, Associations of Friends of Lusatia were founded in Opole and Prudnik.[111] In 1947, eight Sorbian students established the "Lusatia" Association of Sorbian Students of Higher Education of Wrocław, with eight more joining the following year.[112] Also local press in Katowice, Opole and Prudnik published articles about the Sorbs and Lusatia.[113]

In Opole, the "Lusatian Days" (Dni Łużyckie) are organized annually, and the Pro Lusatia. Opolskie Studia Łużycoznawcze yearbook is published since 1999.[111] The Polish-Sorbian Association Pro Lusatia was established in Poland in 2004.[111]

After a proposal to rebuild a pre-war statue of Otto von Bismarck in Bautzen (Budyšin) appeared in 2021, the Sorbs objected and the Serbski Institut, in an open letter, reasoned the objection with the Bismarck government's repressions of the Sorbs, Poles, as well as Danes and French, and Bismarck's calls for the extermination of Poles.[114]

Relations with Czechia

Lusatia was partly or wholly part of the Czech Duchy or Kingdom (also known as Bohemia, in the west) at various times between 1075 and 1635, and several remnants of Czech rule can be found in the region. When Lusatia returned from German to Bohemian (Czech) rule, Sorbs were allowed to return to cities, offices and crafts, and the Sorbian language could be used in public.[36] As result, it was in the lands under Czech rule that the Sorbian culture and language persisted, while the more western original Sorbian territory succumbed to Germanization policies. One of the remnants of Czech rule in the region are the many town coats of arms that include the Czech Lion, as in Drebkau (Drjowk), Görlitz (Zhorjelc), Guben (Gubin), Kamenz (Kamjenc), Löbau (Lubij) and Spremberg (Grodk).

In 1706 the Catholic Sorbian Seminary was founded in Prague.[37] In 1846, the Serbowka [hsb] organization was founded by Sorbian students in Prague, and it issued the Kwětki [hsb] magazine until 1892.

Calls for the incorporation of Lusatia into Czechoslovakia were made after Germany's defeats in both world wars. In 1945, the Czechs established a gymnasium for the Sorbs in Česká Lípa, then relocated to Varnsdorf in 1946 and to Liberec in 1949, however, the Sorbs took their high school diploma in Bautzen after a Sorbian high school was established there.[115]

Relations with Yugoslavia

First permanent cultural and political contacts between Sorbs and South Slavs were established in the mid-19th century, and the contacts reached in their peak in the early 20th century.[116] In 1934, the first and only issue of the Srbska Lužica newspaper was published by consortium Srbska Lužica in Yugoslavia.[116]

In November 1945, Yugoslavia declared support for the freedom aspirations of the Sorbs.[117] On 1 January 1946, the Sorbian National Council appointed Jurij Rjenč as its plenipotentiary representative in Belgrade, soon confirmed by the Yugoslav authorities after his arrival and meetings with several Yugoslav officials.[117] The Military Mission of Yugoslavia (VMJ) to the Allied Control Council established contacts with Sorbian national activists and declared it imperative to legally guarantee the cultural and national rights of the Sorbs, merge Upper and Lower Lusatia into one administrative district, and to halt the settlement of German displaced persons in Sorbian villages.[118] The Military Mission of Yugoslavia assisted Sorbian activists in Berlin with accommodation and catering, and contributed to the rebuilding of the Serbski dom in Bautzen, the chief cultural institution of Sorbs.[119]

Relations with Slovakia

The Lusatian Serbs were supported by Ľudovít Štúr (he also visited this region), as well as Ján Kollár (he helped establish the Matica Serbská) and Martin Hattala (communicated with students of the Serbian Seminary in Prague).[120][121]

The Slovak Matica cooperates with the Maćica Serbska. In 2025, a delegation of the Slovak Matica of the Sorbians (Domowina institution, Sorbian Institute; Bautzen, Hodźij and Storcha) visited the Sorbs at the invitation of the Maćica Serbska.[122]

Remove ads

Demography

Summarize

Perspective

Estimates of demographic history of the Sorb population since 1450:[1][123][124][125]

Sorbian population in the middle of the 19th century:

Sorbs are divided into two ethnographical groups:

- Upper Sorbs (about 40,000 people).[127]

- Lower Sorbs, who speak Lower Sorbian (about 15–20,000 people).[128][1]

The dialects spoken vary in intelligibility in different areas.

- Map of approximate Sorb-inhabited area in Germany

- Map of area and towns inhabited by Sorbs

- Detailed map of Sorb-inhabited area in Germany (in Lower Sorbian)

Diaspora

During the 1840s, many Sorbian émigrés travelled to Australia, along with many ethnic Germans. The first was Jan Rychtar, a Wendish Moravian Brethren missionary who settled in Sydney during 1844.[129] There were two major migrations of Upper Sorbs and Lower Sorbs to Australia, in 1848 and 1850 respectively. The diaspora settled mainly in South Australia – especially the Barossa Valley – as well as Victoria and New South Wales.

A group of over 500 Sorbs, led by the Evangelical Lutheran pastor Jan Kilian, sailed to Galveston in 1854 aboard the ship Ben Nevis. They later founded the settlement of Serbin in Lee County, Texas, near Austin. Two-thirds of the emigrants came from the Prussian part, and one-third from the Saxon part of Upper Lusatia, including about 200 Sorbs from the Klitten area. The Sorbian language, a variant of Upper Sorbian, survived in Serbin until the 1920s, though it was increasingly influenced first by German, then by English. In the past, newspapers in Sorbian were also published in Serbin. Today, the former Sorbian school in Serbin houses the Texas Wendish Heritage Museum, which tells the story of the Sorbs in the USA. Descendants of these emigrants went on to found Concordia University Texas in Austin in 1926.[130]

Remove ads

Institutions

Summarize

Perspective

Domowina

The Domowina, founded in 1912 (a poetic Sorbian term for “homeland”), is the umbrella organization of local chapters, five regional associations, and twelve Sorbian associations active at a supraregional level,[132] with a total of around 7,300 members.[133] Members who are part of more than one affiliated association may be counted multiple times.

Foundation for the Sorbian People

The Foundation for the Sorbian People (Załožba za serbski lud) serves as a joint instrument of the federal government and the states of Brandenburg and Saxony to support the preservation, development, promotion, and dissemination of the Sorbian language, culture, and traditions as an expression of the Sorbian people's identity.

It was initially established in 1991 by decree as a non-legally-capable public foundation within the Protestant Church of Lohsa.[134] Recognizing that the Sorbian people have no kin-state outside the Federal Republic of Germany, and based on the obligations declared in Protocol Note No. 14 to Article 35 of the Unification Treaty, the necessary material framework was thus created. With the signing of the State Treaty between Brandenburg and Saxony on the establishment of the Foundation for the Sorbian People on August 28, 1998, the foundation was granted legal capacity. At the same time, the first funding agreement between the federal government and the states of Brandenburg and Saxony was signed, valid until the end of 2007. Based on the Second Funding Agreement of July 10, 2009, the foundation has since received annual contributions from Saxony, Brandenburg, and the federal government to fulfill its mission. This agreement was valid until December 31, 2013. Until the third agreement was concluded in 2016, the funding amount was determined annually.[134]

The annual funding amount set until 2013 was €16.8 million, divided as follows: Federal Government: €8.2 million, Saxony: €5.85 million and Brandenburg: €2.77 million.[134]

The largest shares of the foundation’s budget went to:

- Sorbian National Ensemble: 29%

- Domowina Publishing House: 17.2%

- Sorbian Institute: 11.3%

- Foundation administration: 11.4%[133]

There have been public controversies over the absolute funding volume and distribution among institutions and projects, some of which led to demonstrations.[135][136]

On July 20, 2021, Federal Interior Minister Horst Seehofer, Brandenburg’s Minister-President Dietmar Woidke, and Saxony’s Minister-President Michael Kretschmer signed the joint funding agreement for the next funding period.[137] The agreement provides for annual funding of €23.916 million from 2021 to 2025.

Institute for Sorbian Studies

On December 10, 1716, six Sorbian theology students founded the “Wendish Preachers' Collegium” (later renamed “Lusatian Preachers’ Society”) with the permission of Leipzig University’s senate—the first Sorbian association ever.[138] Their motto, which was also their greeting, was: “Soraborum saluti!” (For the good of the Sorbs!)

Today, the Institute for Sorbian Studies at Leipzig University is the only institute in Germany where Sorbian teachers and scholars (Sorabists) are trained. Classes are held in both Upper and Lower Sorbian. In recent years, Sorbian studies and its degree programs have attracted increasing interest, particularly from the Slavic-speaking world. Since March 1, 2003, the director of the institute has been Eduard Werner (Sorbian: Edward Wornar).

Sorbian Institute

Since 1951, there has been a non-university research institute for Sorbian studies in Bautzen, which was part of the German Academy of Sciences in East Berlin until 1991. Re-established in 1992 as the Sorbian Institute e. V. (Serbski Institut z. t.), it currently has about 25 permanent employees working at two locations: Bautzen (Saxony) and Cottbus (Brandenburg).

The institute's broad mission includes research into the Sorbian language (both Upper and Lower Sorbian), as well as the history, culture, and identity of the Sorbian people in Upper and Lower Lusatia. Through its various projects, the institute contributes to the practical preservation and development of Sorbian national substance. It is affiliated with the Sorbian Central Library and the Sorbian Cultural Archive, which collect, preserve, and share Sorbian cultural heritage spanning nearly 500 years.

Domowina Publishing House

Also located in Bautzen, the Domowina Publishing House (Ludowe nakładnistwo Domowina) publishes most of the Sorbian books, newspapers, and magazines. It evolved from the VEB Domowina Publishing House, founded in 1958 and reorganized as a GmbH in 1990.

The publishing house is funded by the Foundation for the Sorbian People with €2.9 million (as of 2012). Since 1991, it has operated the Smoler’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Smolerjec kniharnja), named after the Sorbian bookstore founded in 1851 by the first Sorbian publisher Jan Arnošt Smoler (1816–1884).[139]

Sorbian Museum

The Sorbian Museum (Serbski muzej Budyšin) is located in the Salzhaus of the Ortenburg castle complex in Bautzen. Its exhibition offers an overview of Sorbian history from the 6th century to the present, along with insights into Sorbian culture and daily life.

The museum also features rotating special exhibitions of Sorbian visual artists or exhibitions focused on specific historical themes. The museum is operated by the Bautzen district and is supported by the Foundation for the Sorbian People and the Cultural Area of Upper Lusatia–Lower Silesia.

Sorbian National Ensemble

The Sorbian National Ensemble (Serbski ludowy ansambl) is the only professional Sorbian music and dance theater, with departments for orchestra, ballet, and choir. Its repertoire includes dance theater, musical theater, concerts, and children's music theater—ranging from traditional Sorbian to modern styles.

The ensemble’s headquarters are located near the Röhrscheidt Bastion by the Friedensbrücke in Bautzen. Since 1952, the group has toured to over 40 countries on 4 continents, with about 14,000 guest performances.

The ensemble is managed as a non-profit limited company (GGmbH). Its sole shareholder is the Foundation for the Sorbian People, from which it receives over €5 million annually, about one-fifth of the foundation’s total budget.

Schools and kindergartens

In Saxony and Brandenburg, the Sorbian bilingual settlement areas have several bilingual Sorbian-German schools, as well as other schools where Sorbian is taught as a foreign language. In Saxony during the 2013/14 school year, there were eight bilingual elementary schools and six bilingual secondary schools and in Brandenburg, there were four bilingual elementary schools and one combined secondary school with an elementary level.[140][141] High school graduation in Sorbian is possible at the Sorbian Gymnasium in Bautzen and the Lower Sorbian Gymnasium in Cottbus.

There are also several Sorbian kindergartens in both states. The Sorbisches Schulverein (Sorbian School Association), which operates across state borders, launched the “Witaj” (Sorbian for 'welcome') project, promoting bilingual education in kindergartens and schools through language immersion—where children learn Sorbian naturally through everyday interaction.[142]

Remove ads

Media

Summarize

Perspective

A daily Upper Sorbian newspaper, Serbske Nowiny (Sorbian Newspaper), and a weekly Lower Sorbian newspaper, Nowy Casnik (New Newspaper), are published. Additionally, there is the monthly Sorbian cultural magazine Rozhlad (Review), the children’s magazine Płomjo (Flame), the Catholic magazine Katolski Posoł, and the Protestant church newspaper Pomhaj Bóh (God Help). The Sorbian Institute publishes the academic journal Lětopis (Yearbook) every six months. There is also the professional journal for educators, Serbska šula (Sorbian School).

Furthermore, there is Sorbian radio broadcasting, with programming produced by Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) and Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB). Every day, a few hours of Sorbian-language radio programs are broadcast from stations in Calau (RBB) and Hoyerswerda (MDR 1). All Lower Sorbian broadcasts from RBB are also available for replay online. For younger audiences, RBB broadcasts the half-hour monthly magazine Bubak on the first Thursday of each month, and MDR airs the two-hour weekly magazine Radio Satkula every Monday.

Since April 1992, RBB has produced the half-hour Lower Sorbian television magazine Łužyca (Lusatia), aired monthly. Since September 8, 2001, MDR has produced the monthly half-hour Upper Sorbian program Wuhladko (View). In addition, MDR broadcasts Unser Sandmännchen (Our Little Sandman) every Sunday with dual audio (including Sorbian).

Remove ads

Sorbian in literature, film, and television

Summarize

Perspective

Literature

In his Walks through the March of Brandenburg (1862–1889), Theodor Fontane describes not only the history but also the lifestyle, customs, and traditional dress of the Sorbs (Wends) in Lower Lusatia. In Wilhelm Bölsche’s contemporary novel Die Mittagsgöttin (The Midday Goddess) from 1891, some of the scenes are set in the Spreewald, including the then predominantly Lower Sorbian-speaking village of Lehde. Furthermore, the novel Die Mittagsfrau by Julia Franck, published in 2007, is named after the well-known Sorbian mythical figure. The first part of the novel portrays the childhood of Martha and Helene in Bautzen, whose Sorbian maid suspects the curse of the "Mittagsfrau" (Midday Woman) to be the cause of their mother’s mental breakdown.

Film and television

In the GDR, documentaries were produced such as Wie die Sorben den Maibaum aufstellen (How the Sorbs Erect the Maypole) (1956) and Leben am Fließ – W Błotach (1990). The DEFA animated film Als es noch Wassermänner gab is based on a Sorbian fairy tale and also deals with Sorbian wedding customs. In 2010, the ZDF broadcast the crime film Der Tote im Spreewald (The Dead Man in the Spreewald). One of the main characters is the son of a traditionally-minded Sorbian family, who does not feel connected to his cultural roots. The film introduced Sorbian culture to a wider audience, while also reflecting on issues of homeland and minority identity.[143]

In 2007, the Minet – Minderheitenmagazin aired a program on RAI 3 (Bozen station) titled Die Sorben – ein slawisches Volk in Deutschland (The Sorbs – a Slavic People in Germany).[144] Also in 2007, Radiotelevisiun Svizra Rumantscha produced the film Ils Sorbs en la Germania da l’ost (The Sorbs in Eastern Germany) as part of its series Minoritads en l’Europa (Minorities in Europe).[145] The 2020 documentary Sorben ins Kino! by Knut Elstermann focuses on Sorbian filmmakers, including those in the Sorbian Film production group.[146]

In the series Straight Outta Crostwitz, released exclusively on ARD Mediathek in 2022, Jasna Fritzi Bauer plays the Sorbian character Hanka.[147] She sings Sorbian folk songs with her father but actually wants to make rap music. This dramedy-style story of emancipation spans four episodes, each between nine and twelve minutes long, and was also filmed in Lusatia.[148]

On April 18, 2024, the documentary Bei uns heißt sie Hanka premiered in cinemas. Directed by Grit Lemke, the film explores the search for Sorbian identity.[149]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- "[A]nti-Sorbian policies throughout the Sorbian area of settlement got increasingly aggressive and, unsurprisingly, saw their climax under Nazi rule. Sorbs were declared to be "Wendish-speaking Germans" and a "Wendenabteilung was established to monitor the process of assimilation..."[38]

- "Sorbs inhabiting Upper and Lower Lusatia, whose distinct identity and culture were simply denied by the Nazis, who described them as “Wendish-speaking” Germans and who, toward the end of the war, considered moving the Sorbs en masse to the mining districts of Alsace-Lorraine.".[41]

- "The Nazis intended to assimilate and permanently germanize these 'Wendish-speaking Germans' through integration into the 'National Socialist national community' and through the forbidding of the Sorbian language and manifestations of Sorbian culture, Sorbian and Slav place-names and local names of topographical features (fields, hills and so forth) were germanized, Sorbian books and printing presses confiscated and destroyed, Sorbian schoolteachers and clerics removed and put in German-speaking schools and parishes, and representatives of Sorbian cultural life were either forcibly isolated from their fellows or arrested."[42]

- "[A]fter 1933, under the Nazi regime, the Sorbian community suffered severe repression, and their organizations were banned. Indeed, the very existence of the ethnic group was denied and replaced by the theory of the Sorbs as 'Slavic speaking Germans'. Plans were made to re-settle the Sorbian population in Alsace in order to resolve the 'Lusatian question'. The 12 years of Nazi dictatorship was a heavy blow for a separate Sorbian identity."[43]

- "They pressed Sorbian associations to join Nazi organizations, often with Success, and the Domowina received an ultimatum to adopt a statute which defined it as a 'League of Wendish-speaking Germans'.” But the Domowina insisted upon the Slavonic character of the Sorbs. In March 1937 the Nazis forbade the Domowina and the Sorbian papers, all teaching in Sorbian was discontinued, and Sorbian books were removed from the school libraries."[44]

- "[T]he programmatic re-invention of the Sorbian minority as wen- dischsprechende Deutsche under the Nazi regime..."[45]

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads