Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

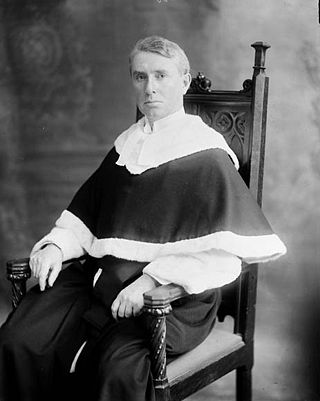

Lyman Duff

Chief Justice of Canada from 1933 to 1944 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sir Lyman Poore Duff, PC PC (Can) GCMG (7 January 1865 – 26 April 1955) was a Canadian lawyer and judge who served as the eighth Chief Justice of Canada. He was the longest-serving justice of the Supreme Court of Canada,[1] until Beverley McLachlin’s 17-year tenure from 2000 to 2017.[2]

Remove ads

Early life and career

Summarize

Perspective

Lyman Duff was born on January 7, 1865 in his family's church in Meaford, Canada West (now Ontario) to Charles Duff, a Congregationalist minister and Isabella Johnson.[3] He was the second of three children. Lyman took his first and middle name after two clergymen present when Charles was ordained as a minister, Revered Lymand and Reverend Poore.[4]

His paternal grandfather Charles Duff was from Perth, Scotland, and his paternal grandmother was from Linby, England,[5] In 1848, Charles immigrated to Canada with two of his sons, including younger Charles who was 16 years old at the time.[6] Charles senior died two years later in 1850 after taking up a farm near Balmoral, Ontario, and his paternal grandmother died shortly afterwards, Charles senior's brother and sister immigrated to join him in Canada shortly after.[6]

Lyman's family moved to Liverpool, Nova Scotia when he was an infant and remained there for 10 years; then returned to Speedside, Ontario.[7] Lyman's formal education through childhood to his legal career was marked with periodic starts and stops. Biographer David Ricardo Williams was often unable to identify the reasons for these stops.[8] For secondary school, Lyman moved between Hamilton Collegiate Institute, Fergus High School, and then moved back to Hamilton Collegiate Institute, where he became friends with John Charles Fields and Douglas Alexander; then later attended St. Catharines Collegiate.[9] Additionally, at an unidentified point Duff attended Jarvis Collegiate Institute in Toronto.[10] In 1881, Duff entered University College at the University of Toronto, where he was active in student life, and became friends with Gordon Hunter, the future Chief Justice of British Columbia and Stuart Alexander Henderson.[11] In 1884 he took a break from school, likely owning to his father only being able to afford to support one of his children at university, choosing his older brother Rolf's law degree.[12] Duff eventually graduated from the University of Toronto, with a Bachelor of Arts in mathematics and metaphysics in 1887, and received an LLB in 1889.[13] Beginning in 1885, he began teaching math, and occasionally French at Barrie Collegiate Institute.[14][12] In 1888, Duff began taking courses at Osgoode Hall Law School, and after some unexplained absences his biographer Williams attributes to a lack of funds, Duff was called to the Ontario Bar in 1893 at the age of 28.[14][15]

While teaching at Barrie, he met the family of Henry Bird, a merchant and town clerk. He became friends with Bird's son and student J. Edward Bird, and in 1898 married Bird's daughter Elizabeth Bird.[13]

During his early career, Duff practised as a lawyer in Fergus, Ontario under N.M. Monro whom he had worked for as a student.[14][16] In 1894, Duff accepted an offer from his friend Gordon Hunter to join him in a partnership in Victoria, British Columbia.[17] The Law Society of British Columbia required new lawyers to reside in the province for six months before they could practice, so Duff earned money reporting on Court proceedings for the Victoria Daily Colonist, he was eventually called to the British Columbia Bar on February 28, 1895.[18] Duff won his first case in Victoria, and later gained a reputation for mining law. He also maintained a limited practice in criminal defence, but his biographer Williams notes that he had little success.[19]

In 1895, he was appointed Queen's Counsel (Q.C.), which became King's Counsel (K.C.) on 22 January 1901 upon the death of Queen Victoria.[20] In 1903, he took part, as junior counsel for Canada, in the Alaska Boundary arbitration.[20]

Remove ads

Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia

In 1904, he was appointed a puisne judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia.

Puisne Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada

Summarize

Perspective

On September 27, 1906, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier nominated Duff for appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada following the death of Justice Robert Sedgewick on August 4, 1906.[21] Duff's appointment was well received by the legal community due to his good reputation and name recognition across Canada.[22]

Biographer Ricardo Williams notes that Duff did not immediately engage with the Court's work, instead in early cases he chose to write short decisions agreeing with another justice.[23] Duff wrote his first decision four months after his appointment.[23][ps 1]

On January 14, 1919, he was appointed to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom.[24] Duff was the first and only Puisne Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada to be appointed to the Imperial Privy Council.[25] In 1924, he was elected as an honorary bencher of Gray's Inn, at the recommendation of Lord Birkenhead.[26]

In the Board of Commerce case (1920), a deadlocked 3–3 Supreme Court was unable to determine the validity of legislation dealing with the federal government's residue power under the peace, order, and good government provision of the British North America Act. Duff ruled against the validity of the legislation, and did not bind himself to the Privy Council's jurisprudence in the Local Prohibition Case.[27] The Privy Council on appeal followed some of Duff's reasoning. Snell and Vaughan note that Board of Commerce represents Duff's emergence as a justice with his own views that went on to influence Canadian constitutional law.[27]

In the Persons case, Duff in separate reasons from Chief Justice Anglin, agreed that women were not persons for the purpose of appointment to the Senate of Canada. Rather than Anglin's narrow originalist interpretation of the framer's intent for the Constitution Act, 1867, Duff did not take a direct stand on the issue. Instead he argued the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy imported under the preamble to the Constitution Act, 1867 and the peace, order and good government residual power of section 91 permitted the Canadian Parliament to set the qualification standards of Senators.[28][ps 2] Ian Bushnell notes that Duff's reasons were politically unpalatable for Prime Minister King.[28]

During his years as a puisne justice, Duff appears to have not made any contribution of civil law cases coming out of Quebec.[29] He did not provide reasons in two leading civil law cases in 1920, and later in a 1933 speech, he noted he was not competent to discuss the development of civil law.[29]

In 1931, he served as Administrator of the Government of Canada (acting Governor-General of Canada) between the departure of Lord Bessborough for England and the arrival of Lord Tweedsmuir.[30] Duff took on the position, as the Chief Justice was unavailable. As Administrator, Duff opened Parliament and read the Speech from the Throne on 12 March 1931, becoming the first Canadian-born person to do so.[31]

In 1931, Duff was named chairman of the Royal Commission into Railways and Transportation in Canada. When the commission completed its final report in 1932, Duff under severe stress suffered what Prime Minister R.B. Bennett described as a "complete nervous breakdown" and was hospitalized. The Prime Minister believed the situation was so severe that Duff would "not likely ever sit on the bench again."[32][33]

Remove ads

Chief Justice of Canada

Summarize

Perspective

In poor health, Chief Justice Francis Alexander Anglin resigned on February 28, 1933, at the age of 67. He died three days later.[34][35] On March 17, 1933, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett selected Duff as the 8th Chief Justice of Canada.[34] There was little evidence that Bennett considered other candidates for the appointment, but Bennett was cautious about the appointment due to Duff's poor health. Duff's appointment was popular among the legal community.[34]

Duff had been passed over for the role of Chief Justice in 1924 by Prime Minister Mackenzie King, owing to his support of the Robert Borden government and his alcoholism.[36] It had been rumored that Duff was intoxicated at the opening of Parliament and the funeral of Chief Justice Davies, and Mackenzie King wrote that Duff's drinking went on for "sprees for weeks at a time."[37] The appointment of Anglin serious hurt Duff's feelings and he considered resigning from the Court.[38] Anglin had written the Justice Department advising against appointing Duff to the role of Chief Justice, and resentment remained between Anglin and Duff during the term.[38]

He was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George the following year[39] as a result of Prime Minister Richard Bennett's temporary suspension of the Nickle Resolution.[ps 3][40]

When Governor General Lord Tweedsmuir died in office on February 11, 1940, Chief Justice Duff became the Administrator of the Government for the second time.[30] He held the office for nearly four months, until King George VI appointed Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone as Governor General on June 21, 1940.[30] Duff was the first Canadian to hold the position, even in the interim. A Canadian-born Governor General was not appointed until Vincent Massey in 1952.[41]

Duff also heard more than eighty appeals on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, mostly Canadian appeals; however, he never heard Privy Council appeals from the Supreme Court of Canada while he served on the latter, otherwise, it would have been seen as a conflict of interest. The last Privy Council appeal heard by Duff was the 1946 Reference Re Persons of Japanese Race.[26]

Duff reached the mandatory retirement age of 75 in January 1940, but bi-partisan support in Parliament extended Duff's tenure for an additional three years.[42][ps 4] To date, this has been the only instance where a justice's mandatory retirement was waived by parliament.[42] The reasons for the extension are not entirely clear, with King's diary only noting the issue of the war;[43] but Duff had a strong reputation as a legal mind.[42] Prime Minister King's diary notes that he felt the Court was weak at the time and in his discussions with Justice Minister Ernest Lapointe they felt there was not a good candidate to replace Duff from British Columbia, or replace him as Chief Justice.[44] In 1943, opposition in parliament grew against Duff's extension with growing age at the age of 78 and his role as the Royal Commission on Canada's deployment to Hong Kong which exonerated the government of fault.[44][43][ps 5][ps 6] Privately, Duff told friends that he feeling his age.[44] Duff retired as Chief Justice on January 7, 1944, after 37 years on the bench.[44][45] The next day, Thibaudeau Rinfret the senior justice on the Court was appointed Chief Justice.[44]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Duff employed a conservative form of statutory interpretation. In a 1935 Supreme Court of Canada judgment, he detailed how judges should interpret statutes:

The judicial function in considering and applying statutes is one of interpretation and interpretation alone. The duty of the court in every case is loyally to endeavour to ascertain the intention of the legislature; and to ascertain that intention by reading and interpreting the language which the legislature itself has selected for the purpose of expressing it.[ps 7]

Duff has been called a "master of trenchant and incisive English," who "wrote his opinions in a style which bears comparison with Holmes or Birkenhead."[46] A former assistant of Duff, Kenneth Campbell, argued that Duff was "frequently ranked as the equal of Justices Holmes and Brandeis of the United States Supreme Court".[47] Gerald Le Dain, an academic and later a judge on the Supreme Court, asserted that Duff "is generally considered to have been one of Canada's greatest judges."[48] Other writers have taken a less favourable view, instead arguing that Duff's reputation is largely unearned; his biographer concluded that he was not an original thinker, but essentially a "talented student and exponent of the law rather than a creator of it."[49]

More recent commentary has focused on Duff's legal formalism and its effect on Canadian federalism. A later successor Chief Justice of Canada, Bora Laskin attacked Duff's decisions, arguing that Duff used circular reasoning and hid his policy-laden decisions behind the doctrine of stare decisis.[50] As well, Lionel Schipper noted that, in reviewing Duff's judgments, it was:

apparent that he has given certain factors very little consideration in formulating his decisions. ... In constitutional cases, not only are the actual facts of the case significant but the surrounding social, economic and political facts are equally significant. A shift in these latter factors is as important in deciding a case as any other change in the facts. It is this consideration that Chief Justice Duff ignored.[51]

In their 1985 review of the history of the Supreme Court of Canada, Snell and Vaughan note that Duff was "most famous justice in the history of the institution [of the Supreme Court of Canada]."[52]

Remove ads

Honours

In 1923, Mount Duff (Yakutat), also known as Boundary Peak 174, was named after him.[53]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads