Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

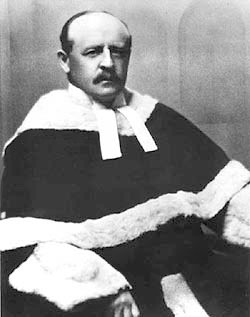

Francis Alexander Anglin

Chief Justice of Canada from 1924 to 1933 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Francis Alexander Anglin PC (April 2, 1865 – March 2, 1933) was a Canadian lawyer and judge who served as the seventh Chief Justice of Canada from 1924 until 1933.[1]

Born in Saint John, New Brunswick, he was the son of Timothy Anglin, a prominent politician and Speaker of the House of Commons, and the brother of acclaimed stage actress Margaret Anglin. After earning degrees in arts and law from the College of Ottawa, Anglin was called to the Ontario Bar in 1888 and quickly established a reputation as a skilled lawyer in Toronto.

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier appointed Anglin to the Ontario High Court of Justice in 1904, and was later elevated to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1909. Both appointments were the result of political patronage. In 1924, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King elevated Anglin to the role of Chief Justice of Canada. He held that position until his retirement due to health issues in 1933. He died three days after his retirement.

Anglin is known as a better than average justice of the Court, who favoured a more expansive interpretation of the federal government's authority in constitutional matters, a position in opposition of the dominate jurisprudence by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. His most notable judgement was in the Persons case where he refused to interpret the term "person" in the Constitution Act, 1867 to include women for the purpose of appointments to the Senate of Canada. Anglin's opinion which was overturned by the Privy Council, is among the most criticized decisions in the history of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Francis Alexander Anglin was born on April 2, 1865, in Saint John, New Brunswick, one of ten children of Timothy Anglin and his wife, Ellen Anglin.[1] His parents had immigrated from Ireland to Saint John in 1849 during the Great Famine. His father became a prominent political figure, serving as Speaker of the House of Commons of Canada and earlier as a member of the New Brunswick House of Assembly, where he opposed the province's entry into Confederation.[1]

Anglin was educated at St. Mary's College in Montreal and the College of Ottawa, from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1885.[1] He then pursued legal studies through the Law Society of Upper Canada, which at the time offered formal instruction, and was called to the Ontario bar in 1888, earning a silver medal in his bar examinations.[1] Anglin articled with the Toronto firm of Blake, Lash and Cassels, led by Edward Blake and Zebulon Aiton Lash.[1] Following his call to the bar, he established a practice in Toronto and entered into partnership with the noted Catholic lawyer Dennis Ambrose O'Sullivan. After O'Sullivan’s death in 1894, Anglin practised with George Dyett Minty, and later with James Woods Mallon, though with limited success.[1]

Following his father's death in 1896, Anglin was appointed Clerk of the Surrogate Court of Ontario, a position he held for three years.[1] He had briefly entered politics the previous year, seeking the Liberal nomination for Renfrew South in 1895, though unsuccessfully.[1] A committed Liberal, he continued to support the party and campaigned for Dilman Kinsey Erb during the 1896 federal election, delivering speeches on his behalf.[1]

Anglin was appointed King's Counsel in 1902.[1] His political activities within the Liberal Party were likely motivated by the hope of securing a judicial appointment.[1] Beginning in 1897, he wrote directly to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier seeking consideration for various vacancies on the Ontario bench, and he enlisted the support of prominent Irish-Catholics, including his mother, several Members of Parliament, bishops, and other political figures to advocate on his behalf.[2] That same year, he was appointed a temporary substitute judge, filling in for Justice Thomas Ferguson on the Ontario High Court of Justice.[1]

In his correspondence with Laurier, Anglin noted his qualifications, lifelong loyalty to the Liberal Party, and the under representation of Catholics on the Ontario judiciary.[2] When no appointment materialized in Ontario, he even offered to serve in British Columbia with an accompanying memo demonstrating the legality of the appointment; suggesting that his presence as an outsider and Catholic would be of value to the province.[3] By 1900, Laurier had grown tired of the persistent lobbying, replying to his supporters that any further correspondence on Anglin's behalf would result in a blanket refusal to his future consideration.[4]

Finally, in 1904, Anglin was appointed to the Exchequer Division of the High Court of Justice of Ontario at the age of 39, after spending 16 years a corporate and commercial practice.[5] The Canada Law Times later noted that he performed his duties with distinction, describing his manner as "uniformly courteous, and often at much inconvenience to himself."[6]

Remove ads

Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada

Summarize

Perspective

On February 23, 1909, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier appointed Anglin to the Supreme Court of Canada following the retirement of Justice James Maclennan earlier on February 13.[7] Laurier's judicial appointments during this period reflected a blend of merit, political patronage, and governmental interest rather than a consistent commitment to the long-term development of the Court.[8] The politicized nature of such appointments, and the Court's use as a political instrument, contributed to what historians Snell and Vaughan have described as an era of institutional decline during the Fitzpatrick Court era.[9] Nevertheless, they note that Anglin stood out among Laurier's appointees for his professional competence and prior judicial experience.[5]

Anglin quickly established himself as an active and independent member of the Court, authoring opinions in significant cases soon after his appointment rather than merely concurring with his colleagues.[10] In 1910, without notifying the other justices, he submitted to the government a draft bill proposing amendments to the Supreme Court Act to permit the appointment of ad hoc judges. The proposal was not acted upon at the time, though the idea was adopted in 1918.[11]

In 1917, Anglin joined Chief Justice Fitzpatrick, Minister of Justice Charles Doherty, and politician Charles Murphy in urging Prime Minister Robert Borden to advocate for Irish home rule within the British Empire.[12]

Anglin's judgment in Re Gray (1918), which upheld Parliament's delegation of broad legislative powers to Cabinet under the War Measures Act during the First World War, was published in advance of the Supreme Court Reports in both The Toronto Globe and the Canadian Law Journal.[13]

Under Justice Pierre-Basile Mignault, the Supreme Court began treating the Quebec Civil Code with a firm judicial pattern of treatment emphasizing the distinct nature of the Civil Code and refusing to apply common law principles. Anglin's concurrence with Mignault and the other Quebec judge Louis-Philippe Brodeur allowed decisions such as Desrosiers v The King (1920) and Curley v Latreille (1920) to become authority for adjudicating civil law cases without the use of English common law traditions.[14][15][ps 1][ps 2]

In 1923, Anglin was selected as Canada's nominee to the newly formed International Court of Justice at The Hague, though he was ultimately not chosen for appointment.[1]

Chief Justice of Canada

On May 1, 1924, Chief Justice Louis Henry Davies died at age 78.[16] Although he had intended to retire in 1921, he remained on the bench amid a dispute over the terms of his pension.[16] Following his death, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King appointed Anglin as the seventh Chief Justice of Canada on September 16, 1924.[17] In keeping with custom, Anglin was sworn into the Imperial Privy Council in 1925 following his elevation to Chief Justice.[18]

Anglin was not King's preferred candidate for Chief Justice. The prime minister had repeatedly offered the position to the distinguished Quebec lawyer Eugène Lafleur, even enlisting Governor General Lord Byng to persuade him, but Lafleur declined each time.[17] At the time of appointment, Anglin was the third most senior member of the Court. He was elevated over Justice John Idington, whose mental capacity had significantly declined and who was later compelled to retire after Parliament introduced a mandatory retirement age of 75 in 1927.[19] Also senior to Anglin was Justice Lyman Duff, widely regarded as the Court's most capable jurist, but his earlier collaboration with Robert Borden's Conservative government and struggles with alcoholism made his appointment politically untenable.[19]

As Chief Justice, Anglin was an outspoken critic of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council serving as Canada's final court of appeal. In a letter to Prime Minister Mackenzie King, he wrote that "my Canadianism" led him to believe that "should finally settle our litigation in this country. If we are competent to make our own laws, we are, or should be, capable of interpreting and administering them," concluding that "it would be best to terminate all appeals to London."[20]

In 1925, Anglin publicly criticized Lord Haldane of the Privy Council for his reasoning in Russell, which had upheld the Canada Temperance Act on the ground that drunkenness in Canada constituted a national disaster warranting emergency intervention.[21][ps 3] Anglin's remarks, delivered in a judgment that rejected Haldane's expansive reading of federal power, were applauded by the Canadian Bar Review.[22]

In the Persons case, Anglin held that women were not "qualified persons" for the purpose of appointment to the Senate of Canada. In his decision he noted the decision to permit the appointment of women to the Senate was a political decision for parliament, and judges should remain focused on the language of the Constitution.[23][ps 4] The decision was overturned on appeal by Lord Sankey of the Privy Council, who held that the term could be read broadly to include women and articulated the now-foundational living tree doctrine doctrine of constitutional interpretation, under which the Constitution is "capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits."[24][25] In subsequent cases, however, Anglin interpreted this principle narrowly.[1]

During the early decades of the Supreme Court, it was customary for each justice to write individual reasons for judgment rather than issuing joint opinions.[26] Combined with the frequent dismissal of appeals due to evenly divided votes, this practice made it difficult to establish clear precedents or discern a coherent judicial philosophy. As a result, the Court often resolved disputes by applying existing legal principles rather than developing new ones.[27] Under Chief Justice Anglin, this individualistic approach began to change. During the 1920s, members of the Canadian Bar Association increasingly called for the Court to issue single majority judgments to clarify the law.[28] Anglin supported this reform, persuading his colleagues to write unified decisions. Where consensus existed, one justice would draft and circulate a majority opinion for review and comment. However, if there was not initial agreement, justices would draft their own individual drafts which would be exchanged.[29]

By 1929, Anglin's health had begun to decline, and he took an extended leave of absence.[30] That autumn, Prime Minister King privately described him as "failing, [and having] lost all his brightness."[30] Anglin continued to take annual leaves throughout the early 1930s. In 1933, after a private conversation with King about retirement, the former prime minister urged him to step down.[31] Eventually the government threatened to initiate a formal inquiry into his health and capacity to continue in office. Under mounting pressure, he resigned in February 1933, effective at the end of the month.[31] On March 2, 1933, just three days after his retirement at the age of 67, Anglin was found dead.[31]

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Anglin was the elder brother of the celebrated stage actress Margaret Anglin, who became Canada's first Broadway star. His sister Eileen Anglin also gained recognition as a stage performer, while his brother Arthur Whyte Anglin pursued a career as a lawyer.[1]

On June 29, 1892, Anglin married Harriett Isabell Fraser. The couple had two sons and three daughters.[1] Their daughter Beatrice later married Livius Percy Sherwood, the son of Sir Percy Sherwood.

Gifted musically, Anglin was an accomplished baritone and for many years sang as a soloist with various choral groups in Toronto.[1] He also composed several pieces, including settings of Salve Regina and Ave Maria, which he performed at St. Michael's Cathedral Basilica, where he frequently sang at major liturgical events. Although he once considered a career in music, he ultimately chose to pursue law.[1]

A devout Catholic, Anglin was regarded as a leading figure in the Irish-Catholic community in Canada prior to his judicial appointment.[1] In 1924, Pope Pius XI appointed him a Knight Commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great, and in 1930 elevated him to Knight Grand Cross.[1] Some contemporaries, including politician Charles Murphy, remarked that Anglin's use of his religious prominence appeared directed more toward advancing his professional standing than toward furthering the Irish-Canadian cause.[1]

Anglin was also active as a legal writer. He authored Trustees' Limitations and Other Relief (Toronto, 1900)[1] and contributed the entry on "Ontario" to the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Historians Snell and Vaughan describe Anglin as a "better than average member of the Court," noting that his judgments were clearly written and understandable.[17] Intellectually, he was a cautious conservative who approached the law through a formalist lens, favouring the consistent application of precedent over judicial innovation.[1] In constitutional matters, he tended to support a broad interpretation of federal authority, as reflected in his opinions in the Board of Commerce case and the Radio Reference.[1]

Anglin's personality, however, was often described in less flattering terms. Mackenzie King remarked that Anglin's wish to remain on the bench despite his declining health was "too vain," and earlier, during the appointment process, characterized him as "narrow, [with] not a pleasant manner, is very vain, but industrious steady and honest, a true liberal at heart."[17] Anglin had actively lobbied Wilfrid Laurier for judicial appointment years earlier, enlisting political and religious allies to advocate on his behalf.[1] As Chief Justice, he regularly hosted dinners attended by prominent politicians, judges, senior civil servants, foreign diplomats, and members of the bar. Although such gatherings may have been intended to foster goodwill between the Court and public life, Anglin's motive was to enhance his personal status.[32]

On the Court, Anglin's relationship with Justice Lyman Duff was strained. Tension arose from Anglin's elevation to Chief Justice despite Duff's seniority and reputation as the Court's leading jurist. Anglin had written to the Department of Justice advising against Duff's appointment to the position.[33] In 1932, while Anglin was abroad, Duff was authorized to act as a deputy to the Governor General during a vice-regal tour of the western provinces. When Anglin returned earlier than expected, he protested the decision, believing the role should have been his by right.[34]

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads