Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Maldives

Island country in South Asia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

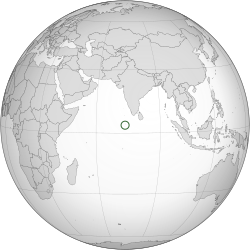

The Maldives,[e] officially the Republic of Maldives,[f] and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, about 750 kilometres (470 miles; 400 nautical miles) from the Asian continent's mainland. The Maldives' chain of 26 atolls stretches across the equator from Ihavandhippolhu Atoll in the north to Addu Atoll in the south.

The Maldives is the smallest country in Asia. Its land area is only 298 square kilometres (115 sq mi), but this is spread over roughly 90,000 square kilometres (35,000 sq mi) of the sea, making it one of the world's most spatially dispersed sovereign states. With a population of 515,132 in the 2022 census, it is the second least populous country in Asia and the ninth-smallest country by area, but also one of the most densely populated countries. The Maldives has an average ground-level elevation of around 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) above sea level,[8] and a highest natural point of only 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in), making it the world's lowest-lying country. Some sources state the highest point, Mount Villingili, as 5.1 metres or 17 feet.[8]

Malé is the capital and the most populated city, traditionally called the "King's Island", where the ancient royal dynasties ruled from its central location.[9] The Maldives has been inhabited for over 2,500 years. Documented contact with the outside world began around 947 AD when Arab travellers began visiting the islands. In the 12th century, partly due to the importance of the Arabs and Persians as traders in the Indian Ocean, Islam reached the Maldivian Archipelago.[10] The Maldives was soon consolidated as a sultanate, developing strong commercial and cultural ties with Asia and Africa. From the mid-16th century, the region came under the increasing influence of European colonial powers, with the Maldives becoming a British protectorate in 1887. Independence from the United Kingdom came in 1965, and a presidential republic was established in 1968 with an elected People's Majlis. The ensuing decades have seen political instability, efforts at democratic reform,[11] and environmental challenges posed by climate change and rising sea levels.[12] The Maldives became a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).

Fishing has historically been the dominant economic activity, and remains the largest sector by far, followed by the rapidly growing tourism industry. The Maldives rates "high" on the Human Development Index,[13] with per capita income significantly higher than other SAARC nations.[14] The World Bank classifies the Maldives as having an upper-middle income economy.[15]

The Maldives is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, and the Non-Aligned Movement, and is a Dialogue Partner of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.[16] It temporarily withdrew from the Commonwealth in October 2016 in protest of allegations of human rights abuses and failing democracy.[17] It rejoined on 1 February 2020 after showing evidence of reform and functioning democratic processes.[18]

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

According to legends, the first settlers of the Maldives were people known as Dheyvis.[19] The first Kingdom of the Maldives was known as Kingdom of Dheeva Maari.[20] During the 3rd century BCE visit of emissaries, it was noted that the Maldives was known as Dheeva Mahal.[19]

During c. 1100 – 1166, the Maldives was also referred to as Diva Kudha, and the Laccadive archipelago which was a part of the Maldives was then referred to as Diva Kanbar by the scholar and polymath al-Biruni.[21]

The name Maldives may also derive from Sanskrit माला mālā (garland) and द्वीप dvīpa (island),[22] or මාල දිවයින Maala Divaina ("Necklace Islands") in Sinhala.[23] The Maldivian people are called Dhivehin. The word Dheeb/Deeb (archaic Dhivehi, related to Sanskrit द्वीप, dvīpa) means "island", and Dhives (Dhivehin) means "islanders" (i.e., Maldivians).[24] In Tamil, "Garland of Islands" can be translated as Mālaitīvu (மாலைத்தீவு).[25]

The venerable Sri Lankan chronicle Mahavamsa mentions an island designated as Mahiladiva ("Island of Women", महिलादिभ) in Pali, likely arising from an erroneous translation of the Sanskrit term, signifying "garland".

Jan Hogendorn, professor of economics at Colby College, theorised that the name Maldives derives from the Sanskrit mālādvīpa (मालाद्वीप), meaning "garland of islands".[22] In Malayalam, "Garland of Islands" can be translated as Maladweepu (മാലദ്വീപ്).[26] In Kannada, "Garland of Islands" can be translated as Maaledweepa (ಮಾಲೆದ್ವೀಪ).[27] None of these names are mentioned in any literature, however, classical Sanskrit texts dating back to the Vedic period mention the "Hundred Thousand Islands" (Lakshadweepa), a generic name which would include not only the Maldives, but also the Laccadives, Aminidivi Islands, Minicoy, and the Chagos island groups.[28][29]

Medieval Muslim travellers such as Ibn Battuta called the islands Maḥal Dībīyāt (محل ديبية) from the Arabic word maḥal ("palace"), which must be how the Berber traveller interpreted the name of Malé, having been through Muslim North India, where Perso-Arabic words were introduced to the local vocabulary.[30] This is the name currently inscribed on the scroll in the Maldives state emblem.[1] The classical Persian/Arabic name for the Maldives is Dibajat.[31][32] The Dutch referred to the islands as the Maldivische Eilanden (pronounced [mɑlˈdivisə ˈʔɛilɑndə(n)]),[33] while the British anglicised the local name for the islands first to the "Maldive Islands" and later to "Maldives".[33]

In a conversational book published in 1563, Garcia de Orta writes: "I must tell you that I have heard it said that the natives do not call it Maldiva but Nalediva. In the Malabar language, nale means four, and diva means island. So that in that language, the word signifies 'four islands', while we, corrupting the name, call it Maldiva."[34]

The local name for Maldives by the Maldivian people in Dhivehi language is "Dhivehi Raajje", (Dhivehi: ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ).[35]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Ancient history and settlement

In the 6th–5th century BCE, the Maldives already had their kingdoms.[19] The country has an established history of over 2,500 years according to historical evidence and legends.[36]

The Mahāvaṃsa (300 BCE) has records of people from Sri Lanka emigrating to the Maldives.[19] Assuming that cowrie shells come from the Maldives, historians believe that there may have been people living in the Maldives during the Indus Valley civilisation (3300–1300 BCE).[37] Several artefacts show the presence of Hinduism in the country before the Islamic period.[19]

According to the book Kitāb fi āthār Mīdhu al-qādimah (كتاب في آثار ميذو القديمة) (On the Ancient Ruins of Meedhoo), written in the 17th century in Arabic by Allama Ahmed Shihabuddine (Allama Shihab al-Din) of Meedhoo in Addu Atoll, the first settlers of the Maldives were people known as Dheyvis.[19] They came from the Kalibanga in India.[19] The time of their arrival is unknown but it was before Emperor Asoka's kingdom in 269–232 BCE. Shihabuddin's story tallies remarkably well with the recorded history of South Asia and that of the copperplate document of the Maldives known as Loamaafaanu.[19]

The ancient history of the Maldives is told in copperplates, ancient scripts carved on coral artefacts, traditions, language, and different ethnicities of Maldivians.[19] The Maapanansa,[19] the copper plates on which were recorded the history of the first Kings of the Maldives from the Solar Dynasty, were lost quite early on.

A 4th-century notice written by Ammianus Marcellinus (362 CE) speaks of gifts sent to the Roman emperor Julian by a deputation from the nation of Divi. The name Divi is very similar to Dheyvi who were the first settlers of Maldives.[19]

The first Maldivians did not leave any archaeological artefacts. Their buildings were probably built of wood, palm fronds, and other perishable materials, which would have quickly decayed in the salt and wind of the tropical climate. Moreover, chiefs or headmen did not reside in elaborate stone palaces, nor did their religion require the construction of large temples or compounds.[38]

Comparative studies of Maldivian oral, linguistic, and cultural traditions confirm that the first settlers were people from the southern shores of the neighbouring Indian subcontinent,[39] including the Giraavaru people, mentioned in ancient legends and local folklore about the establishment of the capital and kingly rule in Malé.[40]

A strong underlying layer of Dravidian and North Indian cultures survives in Maldivian society, with a clear Elu substratum in the language, which also appears in place names, kinship terms, poetry, dance, and religious beliefs.[41] The North Indian system was brought by the original Sinhalese from Sri Lanka. Malabar and Pandya seafaring culture led to the settlement of the Islands by Tamil and Malabar seafarers.[41]

Buddhist period

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2025) |

Despite being just mentioned briefly in most history books, the 1,400 year-long Buddhist period has a foundational importance in the history of the Maldives. It was during this period that the culture of the Maldives both developed and flourished, a culture that survives today. The Maldivian language, early Maldive scripts, architecture, ruling institutions, customs, and manners of the Maldivians originated at the time when the Maldives were a Buddhist kingdom.[42]

Buddhism probably spread to the Maldives in the 3rd century BCE at the time of Emperor Ashoka's expansion and became the dominant religion of the people of the Maldives until the 12th century. Archeological evidence from an ancient Buddhist monastery in Kaashidhoo has been dated between 205 and 560 AD, based on the radiocarbon dating of shell deposits unearthed from the foundations of stupas and other structures in the monastery.[43] The ancient Maldivian Kings promoted Buddhism, and the first Maldive writings and artistic achievements, in the form of highly developed sculpture and architecture, originate from that period. Nearly all archaeological remains in the Maldives are from Buddhist stupas and monasteries, and all artefacts found to date display characteristic Buddhist iconography.[citation needed]

Islamic period

The importance of the Arabs as traders in the Indian Ocean by the 12th century may partly explain why the last Buddhist king of the Maldives, Dhovemi, converted to Islam in the year 1153 (or 1193). Adopting the Muslim title of Sultan Muhammad al-Adil, he initiated a series of six Islamic dynasties that lasted until 1932 when the sultanate became elective. The formal title of the sultan up to 1965 was, Sultan of Land and Sea, Lord of the twelve-thousand islands and Sultan of the Maldives which came with the style Highness.

A Moroccan traveller named Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari is traditionally cited for this conversion.[44] According to the story told to Ibn Battutah, a mosque was built with the inscription: 'The Sultan Ahmad Shanurazah accepted Islam at the hand of Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.'[44][45] Some scholars have suggested the possibility of Ibn Battuta misreading Maldive texts, and having a bias towards the North African, Maghrebi narrative of this Shaykh, instead of the Persian origins account that was known as well at the time.[46]

Others have it that he may have been from the Persian town of Tabriz.[47] This interpretation, held by the more reliable local historical chronicles, Raadavalhi and Taarikh,[48][49] is that Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari was Abdul Barakat Yusuf Shams ud-Dīn at-Tabrīzī, also locally known as Tabrīzugefānu.[50] In the Arabic script the words al-Barbari and al-Tabrizi are very much alike, since at the time, Arabic had several consonants that looked identical and could only be differentiated by overall context (this has since changed by the addition of dots above or below letters to clarify pronunciation – For example, the letter "B" in modern Arabic has a dot below, whereas the letter "T" looks identical except there are two dots above it). "ٮوسڡ الٮٮرٮرى" could be read as "Yusuf at-Tabrizi" or "Yusuf al-Barbari".[51]

The venerated tomb of the scholar now stands on the grounds of Medhu Ziyaaraiy, across the street from the Friday Mosque, or Hukuru Miskiy, in Malé. Originally built in 1153 and re-built in 1658,[52] this is one of the oldest surviving mosques in the Maldives. Following the Islamic concept that before Islam there was the time of Jahiliya (ignorance), in the history books used by Maldivians the introduction of Islam at the end of the 12th century is considered the cornerstone of the country's history. Nonetheless, the cultural influence of Buddhism remains, a reality directly experienced by Ibn Battuta during his nine months there sometime between 1341 and 1345, serving as a chief judge and marrying into the royal family of Omar I.[53] For he became embroiled in local politics and left when his strict judgements in the laissez-faire island kingdom began to chafe with its rulers. In particular, he was angered at the local women going about with no clothing above the waist— a cultural epithet of the region at the time- was seen as a violation of Middle Eastern Islamic rules of modesty—and the locals taking no notice when he complained.[54]

Compared to the other areas of South Asia, the conversion of the Maldives to Islam happened relatively late. The Maldives remained a Buddhist kingdom for another 500 years. Arabic became the prime language of administration (instead of Persian and Urdu), and the Maliki school of jurisprudence was introduced, both hinting at direct contact with the core of the Arab world.[citation needed]

Middle Eastern seafarers had just begun to take over the Indian Ocean trade routes in the 10th century and found the Maldives to be an important link in those routes as the first landfall for traders from Basra sailing to Southeast Asia. Trade involved mainly cowrie shells—widely used as a form of currency throughout Asia and parts of the East African coast—and coir fibre. The Bengal Sultanate, where cowrie shells were used as legal tender, was one of the principal trading partners of the Maldives. The Bengal–Maldives cowry shell trade was the largest shell currency trade network in history.[55]

The other essential product of the Maldives was coir, the fibre of the dried coconut husk, resistant to saltwater. It stitched together and rigged the dhows that plied the Indian Ocean. Maldivian coir was exported to Sindh, China, Yemen, and the Persian Gulf.

Protectorate period

In 1558, the Portuguese established a small garrison with a Viador (Viyazoaru), or overseer of a factory (trading post) in the Maldives, which they administered from their main colony in Goa. Their attempts to forcefully impose Christianity with the threat of death provoked a local revolt led by Muhammad Thakurufaanu al-A'uẓam, his two brothers, and Dhuvaafaru Dhandahele, who fifteen years later drove the Portuguese out of the Maldives. This event is now commemorated as National Day which is known as Qaumee Dhuvas (literally meaning "National" and "Day"). It is celebrated on the 1st of Rabi' al-Awwal, the third month of Hijri (Islamic) calendar.

In the mid-17th century, the Dutch, who had replaced the Portuguese as the dominant power in Ceylon, established hegemony over Maldivian affairs without involving themselves directly in local matters, which were governed according to centuries-old Islamic customs.

The British expelled the Dutch from Ceylon in 1796 and included the Maldives as a British protectorate. The status of the Maldives as a British protectorate was officially recorded in an 1887 agreement in which the sultan Muhammad Mueenuddeen II accepted British influence over Maldivian external relations and defence while retaining home rule, which continued to be regulated by Muslim traditional institutions in exchange for an annual tribute. The status of the islands was akin to other British protectorates in the Indian Ocean region, including Zanzibar and the Trucial States.

In the British period, the Sultan's powers were taken over by the Chief Minister, much to the chagrin of the British Governor-General who continued to deal with the ineffectual Sultan. Consequently, Britain encouraged the development of a constitutional monarchy, and the first Constitution was proclaimed in 1932. However, the new arrangements favoured neither the Sultan nor the Chief Minister, but rather a young crop of British-educated reformists. As a result, angry mobs were instigated against the Constitution which was publicly torn up.

The Maldives remained a British crown protectorate until 1953 when the sultanate was suspended and the First Republic was declared under the short-lived presidency of Mohamed Amin Didi. While serving as prime minister during the 1940s, Didi nationalised the fish export industry. As president, he is remembered as a reformer of the education system and an advocate of women's rights. Conservatives in Malé ousted his government, and during a riot over food shortages, Didi was beaten by a mob and died on a nearby island.

Beginning in the 1950s, the political history in the Maldives was largely influenced by the British military presence on the islands. In 1954, the restoration of the sultanate perpetuated the rule of the past. Two years later, the United Kingdom obtained permission to reestablish its wartime RAF Gan airfield in the southernmost Addu Atoll, employing hundreds of locals. In 1957, however, the new prime minister, Ibrahim Nasir, called for a review of the agreement. Nasir was challenged in 1959 by a local secessionist movement in the three southernmost atolls that benefited economically from the British presence on Gan. This group cut ties with the Maldives government and formed an independent state, the United Suvadive Republic with Abdullah Afeef as president and Hithadhoo as its capital. One year later the Suvadive Republic was scrapped after Nasir sent gunboats from Malé with government police, and Abdullah Afeef went into exile. Meanwhile, in 1960 the Maldives allowed the United Kingdom to continue to use both the Gan and the Hithadhoo facilities for thirty years, with the payment of £750,000 from 1960 to 1965 for the Maldives' economic development. The base was closed in 1976 as part of the larger British withdrawal of permanently stationed forces 'East of Suez'.[57]

Independence and republic

When the British became increasingly unable to continue their colonial hold on Asia and were losing their colonies to the indigenous populations who wanted freedom, on 26 July 1965 an agreement was signed on behalf of the Sultan by Ibrahim Nasir Rannabandeyri Kilegefan, Prime Minister, and on behalf of the British government by Sir Michael Walker, British Ambassador-designate to the Maldive Islands, which formally ended the British authority on the defence and external affairs of the Maldives.[58] The islands thus achieved independence, with the ceremony taking place at the British High Commissioner's Residence in Colombo. After this, the sultanate continued for another three years under Sir Muhammad Fareed Didi, who declared himself King upon independence.[59]

On 15 November 1967, a vote was taken in parliament to decide whether the Maldives should continue as a constitutional monarchy or become a republic.[60] Of the 44 members of parliament, 40 voted in favour of a republic. On 15 March 1968, a national referendum was held on the question, and 93.34% of those taking part voted in favour of establishing a republic.[61] The republic was declared on 11 November 1968, thus ending the 853-year-old monarchy, which was replaced by a republic under the presidency of Ibrahim Nasir.[62] As the King had held little real power, this was seen as a cosmetic change and required few alterations in the structures of government.

Tourism began to be developed on the archipelago by the beginning of the 1970s.[63] The first resort in the Maldives was Kurumba Maldives which welcomed the first guests on 3 October 1972.[64] The first accurate census was held in December 1977 and showed 142,832 people living in the Maldives.[65]

Political infighting during the 1970s between Nasir's faction and other political figures led to the 1975 arrest and exile of elected prime minister Ahmed Zaki to a remote atoll.[66] Economic decline followed the closure of the British airfield at Gan and the collapse of the market for dried fish, an important export. With support for his administration faltering, Nasir fled to Singapore in 1978, with millions of dollars from the treasury.[67]

Maumoon Abdul Gayoom began his 30-year role as president in 1978, winning six consecutive elections without opposition. His election was seen as ushering in a period of political stability and economic development given Maumoon's priority to develop the poorer islands. Tourism flourished and increased foreign contact spurred development. However, Maumoon's rule was controversial, with some critics saying Maumoon was an autocrat who quelled dissent by limiting freedoms and practising political favouritism.[68]

A series of coup attempts (in 1980, 1983, and 1988) by Nasir supporters and business interests tried to topple the government without success. While the first two attempts met with little success, the 1988 coup attempt involved a roughly 80-strong mercenary force of the PLOTE who seized the airport and caused Maumoon to flee from house to house until the intervention of 1,600 Indian troops airlifted into Malé restored order.

The November 1988 coup d'état was headed by Ibrahim Lutfee, a businessman, and Sikka Ahmed Ismail Manik, the father of the former first lady of the Maldives Fazna Ahmed.[69] The attackers were defeated by then National Security Services of Maldives.[70] On the night of 3 November 1988, the Indian Air Force airlifted a parachute battalion group from Agra and flew them over 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) to the Maldives.[70] By the time Indian armed forces reached the Maldives, the mercenary forces has already left Malé on the hijacked ship MV Progress Light.[70] The Indian paratroopers landed at Hulhulé and secured the airfield and restored the government rule at Malé within hours.[70] The brief operation labelled Operation Cactus, also involved the Indian Navy that assisted in capturing the freighter MV Progress Light and rescued the hostages and crew.[70]

21st century

The Maldives were devastated by a tsunami on 26 December 2004, following the Indian Ocean earthquake. Only nine islands were reported to have escaped any flooding,[71][72] while fifty-seven islands faced serious damage to critical infrastructure, fourteen islands had to be totally evacuated, and six islands were destroyed. A further twenty-one resort islands were forced to close because of tsunami damage. The total damage was estimated at more than US$400 million, or some 62% of the GDP.[73] 102 Maldivians and 6 foreigners reportedly died in the tsunami.[68] The destructive impact of the waves on the low-lying islands was mitigated by the fact there was no continental shelf or land mass upon which the waves could gain height. The tallest waves were reported to be 14 feet (4.3 m) high.[74]

During the later part of Maumoon's rule, independent political movements emerged in the Maldives, which challenged the then-ruling Dhivehi Rayyithunge Party (Maldivian People's Party, MPP) and demanded democratic reform. The dissident journalist and activist Mohamed Nasheed founded the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) in 2003 and pressured Maumoon into allowing gradual political reforms.[75] In 2008, a new constitution was approved and the first direct presidential elections occurred, which were won by Nasheed in the second round. His administration faced many challenges, including the huge debt left by the previous government, the economic downturn following the 2004 tsunami, overspending using overprinting of local currency (the rufiyaa), unemployment, corruption, and increasing drug use.[76][unreliable source?] Taxation on goods was imposed for the first time in the country, and import duties were reduced on many goods and services. Universal health insurance (Aasandha) and social welfare benefits were given to those aged 65 years or older, single parents, and those with special needs.[68]

Social and political unrest grew in late 2011, following opposition campaigns in the name of protecting Islam. Nasheed controversially resigned from office after a large number of police and army mutinied in February 2012. Nasheed's vice-president, Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik, was sworn in as president.[77] Nasheed was later arrested,[78] convicted of terrorism, and sentenced to 13 years. The trial was widely seen as flawed and political. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called for Nasheed's immediate release.[79]

The 2013 Maldivian presidential election results were highly contested. Former president Nasheed won the most votes in the first round, but the Supreme Court annulled it despite the positive assessment of international election observers. In the re-run vote Abdulla Yameen, the half-brother of the former president Maumoon, assumed the presidency.[75] Yameen survived an assassination attempt in late 2015.[80] Vice-president Mohamed Jameel Ahmed was removed from office after a no confidence motion from the People's Majlis, it was alleged that he was conspiring with opposition political parties and planning riots.[81] Vice-president Ahmed Adeeb was later arrested together with 17 supporters for "public order offences" and the government instituted a broader crackdown against his accomplices. A state of emergency was later declared ahead of a planned anti-government rally,[82] and the People's Majlis (parliament) accelerated the removal of Adeeb.[83][84]

In the 2018 election, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih won the most votes, and was sworn in as the Maldives' new president in November 2018. Adeeb was freed by courts in Male in July 2019 after his conviction on charges of terrorism and corruption was overruled but was placed under a travel ban after the state prosecutor appealed the order in a corruption and money laundering case. Adeeb escaped in a tugboat to seek asylum in India. It is understood that the Indian Coast Guard escorted the tugboat to the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL) and he was then "transferred" to a Maldivian Coast Guard ship, where officials took him into custody.[85] Former president Abdulla Yameen was sentenced to five years in prison in November 2019 for money laundering. The High Court upheld the jail sentence in January 2021.[86] However, Supreme Court overturned Yameen's conviction in November 2021.[87]

In the 2023 election, People's National Congress (PNC) candidate Mohamed Muizzu won the second-round runoff of the Maldives presidential election, beating incumbent president, Ibrahim Solih, with 54% of the vote.[88] On 17 October 2023, Mohamed Muizzu was sworn in as the eighth President of the Republic of Maldives.[89] Mohamed Muizzu is widely seen to be pro-China, souring relations with India.[90] In 2024, ex-President Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom was freed from his 11-year conviction and the High Court ordered a new trial.[91]

Remove ads

Geography

Summarize

Perspective

The Maldives consists of 1,192 coral islands grouped in a double chain of 26 atolls, that stretch along a length of 871 kilometres (541 miles) north to south, 130 kilometres (81 miles) east to west, spread over roughly 90,000 square kilometres (35,000 sq mi), of which only 298 km2 (115 sq mi) is dry land, making this one of the world's most dispersed countries. It lies between latitudes 1°S and 8°N, and longitudes 72° and 74°E. The atolls are composed of live coral reefs and sand bars, situated atop a submarine ridge 960 kilometres (600 mi) long that rises abruptly from the depths of the Indian Ocean and runs north to south.

Only near the southern end of this natural coral barricade do two open passages permit safe ship navigation from one side of the Indian Ocean to the other through the territorial waters of the Maldives. For administrative purposes, the Maldivian government organised these atolls into 21 administrative divisions. The largest island of the Maldives is that of Gan, which belongs to Laamu Atoll or Hahdhummathi Maldives. In Addu Atoll, the westernmost islands are connected by roads over the reef (collectively called Link Road), and the total length of the road is 14 km (9 mi).

The Maldives is the lowest country in the world, with maximum and average natural ground levels of only 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) and 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) above sea level, respectively. In areas where construction exists, however, this has been increased to several metres. More than 80 per cent of the country's land is composed of coral islands which rise less than one metre above sea level.[92] As a result, the Maldives are in danger of being submerged due to rising sea levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that, at current rates, sea-level rise would be high enough to make the Maldives uninhabitable by 2100.[93][94]

Climate

The Maldives has a tropical monsoon climate (Am) under the Köppen climate classification, which is affected by the large landmass of South Asia to the north. Because the Maldives has the lowest elevation of any country in the world, the temperature is constantly hot and often humid. The presence of this landmass causes differential heating of land and water. These factors set off a rush of moisture-rich air from the Indian Ocean over South Asia, resulting in the southwest monsoon. Two seasons dominate the Maldives' weather: the dry season associated with the winter northeastern monsoon and the rainy season associated with the southwest monsoon which brings strong winds and storms.[95]

The shift from the dry northeast monsoon to the moist southwest monsoon occurs during April and May. During this period, the southwest winds contribute to the formation of the southwest monsoon, which reaches the Maldives at the beginning of June and lasts until the end of November. However, the weather patterns of the Maldives do not always conform to the monsoon patterns of South Asia. The annual rainfall averages 254 centimetres (100 in) in the north and 381 centimetres (150 in) in the south.[96][95]

The monsoonal influence is greater in the north of the Maldives than in the south, more influenced by the equatorial currents.

The average high temperature is 31.5 degrees Celsius and the average low temperature is 26.4 degrees Celsius.[95]

Sea level rise

In 1988, Maldivian authorities claimed that sea rise would "completely cover this Indian Ocean nation of 1,196 small islands within the next 30 years."[99]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's 2007 report predicted the upper limit of the sea level rise will be 59 centimetres (23 in) by 2100, which means that most of the republic's 200 inhabited islands may need to be abandoned.[100] According to researchers from the University of Southampton, the Maldives are the third most endangered island nation due to flooding from climate change as a percentage of population.[101]

In 2008, Nasheed announced plans to look into purchasing new land in India, Sri Lanka, and Australia because he was concerned about global warming, and the possibility of much of the islands being inundated with water from rising sea levels. The purchase of land will be made from a fund generated by tourism. The president explained his intentions: "We do not want to leave the Maldives, but we also do not want to be climate refugees living in tents for decades".[102]

At the 2009 International Climate Talks, Nasheed stated that:

For us swearing off fossil fuels is not only the right thing to do, but it is also in our economic self-interest... Pioneering countries will free themselves from the unpredictable price of foreign oil; they will capitalise on the new green economy of the future, and they will enhance their moral standing giving them greater political influence on the world stage.[103]

Former president Mohamed Nasheed said in 2012 "If carbon emissions continue at the rate they are climbing today, my country will be underwater in seven years."[104] He has called for more climate change mitigation action while on the American television shows The Daily Show[105] and the Late Show with David Letterman,[104] and hosted "the world's first underwater cabinet meeting" in 2009 to raise awareness of the threats posed by climate change.[106][107] Concerns over rising sea levels have also been expressed by Nasheed's predecessor, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom.[108]

In 2020, a three-year study at the University of Plymouth which looked at the Maldives and the Marshall Islands, found that tides move sediment to create a higher elevation, a morphological response that the researchers suggested could help low-lying islands adjust to sea level rise and keep the islands habitable. The research also reported that sea walls were compromising islands' ability to adjust to rising sea levels and that island drowning is an inevitable outcome for islands with coastal structures like sea walls.[109] Hideki Kanamaru, natural resources officer with the Food and Agriculture Organization in Asia-Pacific, said the study provided a "new perspective" on how island nations could tackle the challenge of sea-level rise, and that even if islands can adapt naturally to higher seas by raising their own crests, humans still needed to double down on global warming and protection for island populations.[107]

Environment

Environmental issues other than sea level rise include bad waste disposal and sand theft. Although the Maldives are kept relatively pristine and little litter can be found on the islands, most waste disposal sites are often substandard. The bulk of the waste from Malé and nearby resorts in the Maldives is disposed of at Thilafushi, an industrial island on top of a lagoon reclaimed in the early '90s to sort waste management issues which had plagued the capital and surrounding islands.[110]

31 protected areas are administered by the Ministry of Climate Change, Environment and Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of the Maldives.[111]

Marine ecosystem

The Maldives have a range of different habitats including deep sea, shallow coast, and reef ecosystems, fringing mangroves, wetlands, and dry land. There are 187 species of coral forming the coral reefs. This area of the Indian Ocean, alone, houses 1,100 species of fish, 5 species of sea turtle, 21 species of whale and dolphin, 400 species of mollusc, and 83 species of echinoderms. The area is also populated by several crustacean species: 120 copepods, and 15 amphipods, as well as more than 145 crab and 48 shrimp species.[112]

Among the many marine families represented are pufferfish, fusiliers, jackfish, lionfish, oriental sweetlips, reef sharks, groupers, eels, snappers, bannerfish, batfish, humphead wrasse, spotted eagle rays, scorpionfish, lobsters, nudibranches, angelfish, butterflyfish, squirrelfish, soldierfish, glassfish, surgeonfish, unicornfish, triggerfish, Napoleon wrasse, and barracuda.[113][114]

These coral reefs are home to a variety of marine ecosystems that vary from planktonic organisms to whale sharks. Sponges have gained importance as five species have displayed anti-tumor and anti-cancer properties.[115]

In 1998, sea-temperature warming of as much as 5 °C (9.0 °F) due to a single El Niño phenomenon event caused coral bleaching, killing two-thirds of the nation's coral reefs.[116]

To induce the regrowth of the reefs, scientists placed electrified cones anywhere from 20–60 feet (6.1–18.3 m) below the surface to provide a substrate for larval coral attachment. In 2004, scientists witnessed corals regenerating. Corals began to eject pink-orange eggs and sperm. The growth of these electrified corals was five times faster than untreated corals.[116] Scientist Azeez Hakim stated:

Before 1998, we never thought that this reef would die. We had always taken for granted that these animals would be there, that this reef would be there forever. El Niño gave us a wake-up call that these things are not going to be there forever. Not only this, but they also act as a natural barrier against tropical storms, floods, and tsunamis. Seaweeds grow on the skeletons of dead coral.

— [113]

Again, in 2016, the coral reefs of the Maldives experienced a severe bleaching incident. Up to 95% of coral around some islands have died, and, even after six months, 100% of young coral transplants died. The surface water temperatures reached an all-time high in 2016, at 31 degrees Celsius in May.[117]

Recent scientific studies suggest that the faunistic composition can vary greatly between neighbour atolls, especially in terms of benthic fauna. Differences in terms of fishing pressure (including poaching) could be the cause.[118]

Wildlife

Clockwise from top left: Tawny nurse sharks near Vaavu Atoll, pier in Addu City, Butorides striata, and Ixora sp.

The wildlife of the Maldives includes the flora and fauna of the islands, reefs, and the surrounding ocean. Recent scientific studies suggest that the fauna varies greatly between atolls following a north–south gradient, but important differences between neighbouring atolls were also found (especially in terms of sea animals), which may be linked to differences in fishing pressure – including poaching.[119]

The terrestrial habitats of the Maldives are confronted with a significant threat as extensive development encroaches swiftly upon the limited land resources. Once seldom frequented, previously uninhabited islands now teeter on the brink of extinction, virtually devoid of untouched expanses. Over recent decades of intensive development, numerous natural environments crucial to indigenous species have suffered severe endangerment or outright destruction.

Coral reef habitats have been damaged, as the pressure for land has brought about the creation of artificial islands. Some reefs have been filled with rubble with little regard for the changes in the currents on the reef shelf and how the new pattern would affect coral growth and its related life forms on the reef edges.[120] Mangroves thrive in brackish or muddy regions of the Maldives. The archipelago hosts fourteen species spanning ten genera, among which is the fern Acrostichum aureum, indigenous to these islands.[121]

The waters surrounding the Maldives boast an extensive array of marine life, showcasing a vibrant tapestry of corals and over 2,000 species of fish.[122] From the dazzling hues of reef fish to the majestic presence of the blacktip reef shark, moray eels, and a diverse range of rays including manta rays, stingrays, and eagle rays, the seas teem with life. Notably, the Maldivian waters harbour the magnificent whale shark. Renowned for its biodiversity, these waters host rare species of both biological and commercial significance, with tuna fisheries representing a longstanding traditional resource. Within the limited freshwater habitats such as ponds and marshes, freshwater fish such as the milkfish (Chanos chanos) and various smaller species thrive. Additionally, the introduction of the tilapia or mouth-breeder, facilitated by a United Nations agency in the 1970s, further enriches the aquatic diversity of the Maldives.

Due to their diminutive size, land-dwelling reptiles are scarce on the Maldivian islands. Among the limited terrestrial reptilian inhabitants are a species of gecko and the oriental garden lizard (Calotes versicolor), alongside the white-spotted supple skink (Riopa albopunctata), the Indian wolf snake (Lycodon aulicus), and the Brahmin blind snake (Ramphotyphlops braminus).

In the surrounding seas, however, a more diverse array of reptilian life thrives. Maldivian beaches serve as nesting grounds for the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), the hawksbill sea turtle, and the leatherback sea turtle. Furthermore, saltwater crocodiles have been reported to occasionally reach the islands, taking residence in marshy regions.[123]

The location of this Indian Ocean archipelago means that its avifauna is mainly restricted to pelagic birds.[124] Most of the species are Eurasian migratory birds, only a few being typically associated with the Indian sub-continent. Some, like the frigatebird, are seasonal. Some birds dwell in marshes and island bush, like the grey heron and the moorhen. White terns are found occasionally on the southern islands due to their rich habitats.[125]

Remove ads

Government and politics

Summarize

Perspective

Mohamed Muizzu, President since 2023

Hussain Mohamed Latheef, Vice-President since 2023

The Maldives is a presidential constitutional republic, with extensive influence of the president as head of government and head of state. The president heads the executive branch and appoints the cabinet which is approved by the People's Majlis (Parliament). He leads the armed forces. The current president serving since 17 November 2023 is Mohamed Muizzu.[126][127] President of the Maldives and Members of the unicameral Majlis serve five-year terms.[128] The total number of members are determined by atoll populations. At the 2024 parliamentary election, the People's National Congress (PNC) won a super-majority over the 93 constituencies.[129]

The republican constitution came into force in 1968 and was amended in 1970, 1972, and 1975.[130] On 27 November 1997 it was replaced by another Constitution assented to by then-President Maumoon. This Constitution came into force on 1 January 1998.[131] The current Constitution of Maldives was ratified by President Maumoon on 7 August 2008, and came into effect immediately, replacing and repealing the constitution of 1998. This new constitution includes a judiciary run by an independent commission, and independent commissions to oversee elections and fight corruption. It also reduces the executive powers vested under the president and strengthens the parliament. All state that the president is head of state, head of government, and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces of the Maldives.

In 2018, the then ruling Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM-Y)'s tensions with opposition parties and the subsequent crackdown was termed as an "assault on democracy" by the UN Human Rights chief.[132]

In the April 2019 parliamentary election The Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) of President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih won a landslide victory. It took 65 of 87 seats of the parliament.[133] This was the first time a single party was able to get such a high number of seats in the parliament in Maldivian history.[134]

Order of Nishanizzuddeen is the Maldives' highest civilian honour that can be bestowed upon a person. It is awarded by the president, usually in an elaborate ceremony.[135]

In April 2024, President Mohamed Muizzu's pro-China People's National Congress (PNC) won 66 seats in the 2024 Maldivian parliamentary election, while its allies took nine, giving the president the backing of 75 legislators in the 93-member house, meaning a super-majority and enough to change the constitution.[136]

Law

According to the Constitution of Maldives, "the judges are independent, and subject only to the Constitution and the law. When deciding matters on which the Constitution or the law is silent, judges must consider Islamic Shari'ah".[137]

Islam is the official religion of the Maldives and open practice of any other religion is forbidden.[138] The 2008 constitution says that the republic "is based on the principles of Islam" and that "no law contrary to any principle of Islam can be applied". Non-Muslims are prohibited from becoming citizens.[139]

The requirement to adhere to a particular religion and prohibition of public worship following other religions is contrary to Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which the Maldives has recently become party[140] and was addressed in the Maldives' reservation in adhering to the Covenant claiming that "The application of the principles set out in Article 18 of the Covenant shall be without prejudice to the Constitution of the Republic of Maldives."[141]

A new penal code came into effect on 16 July 2015, replacing the 1968 law, the first modern, comprehensive penal code to incorporate the major tenets and principles of Islamic law.[142][143]

Same-sex relations are illegal in the Maldives, although tourist resorts typically operate as exceptions to this law.[144][145][146]

Foreign relations

Since 1996, the Maldives has been the official progress monitor of the Indian Ocean Commission. In 2002, the Maldives began to express interest in the commission but as of 2008[update] had not applied for membership. Maldives' interest relates to its identity as a small island state, especially economic development and environmental preservation, and its desire for closer relations with France, a main actor in the IOC region.

The Maldives is a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). The republic joined the Commonwealth in 1982, some 17 years after gaining independence from the United Kingdom. In October 2016, the Maldives announced its withdrawal from the Commonwealth[147] in protest at allegations of human rights abuse and failing democracy.[148] The Maldives enjoys close ties with Commonwealth members Seychelles and Mauritius. The Maldives and Comoros are also both members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. Following his election as president in 2018, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih and his Cabinet decided that the Maldives would apply to rejoin the Commonwealth,[149] with readmission occurring on 1 February 2020.[150]

As a result of sanctions imposed upon the Russian oligarchs by the West in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, many of them sought refuge for their mega-yachts in the Maldives due to the absence of an extradition treaty with the United States and other countries.[151]

Following a cabinet meeting, in June 2024, the government of the Maldives decided to ban Israeli passport holders from entering the country, as a response to the ongoing Gaza war.[152][153][154]

Military

The Maldives National Defence Force is the combined security organisation responsible for defending the security and sovereignty of the Maldives, having the primary task of being responsible for attending to all internal and external security needs of the Maldives, including the protection of the Exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the maintenance of peace and security.[155] The MNDF component branches are the Coast Guard, Marine Corps, Special Forces, Service Corps, Defence Intelligence Service, Military Police, Corps of Engineers, Special Protection Group, Medical Corps, Adjutant General's Corps, Air Corps, and Fire and Rescue Service. The Maldives has an arrangement with India allowing cooperation on radar coverage.

As a water-bound nation, much of its security concerns life at sea. Almost 99% of the country is covered by sea and the remaining 1% land is scattered over an area of 800 km (497 mi) × 120 km (75 mi), with the largest island being not more than 8 km2 (3 sq mi). Therefore, the duties assigned to the MNDF of maintaining surveillance over the Maldives' waters and providing protection against foreign intruders poaching in the EEZ and territorial waters, are immense tasks from both logistical and economic viewpoints. The Coast Guard plays a vital role in carrying out these functions. To provide timely security its patrol boats are stationed at various MNDF Regional Headquarters. The Coast Guard is also assigned to respond to maritime distress calls and to conduct search and rescue operations promptly. In 2019, the Maldives signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[156]

Human rights

Human rights in the Maldives is a contentious issue. In its 2011 Freedom in the World report, Freedom House declared the Maldives "Partly Free", claiming a reform process that had made headway in 2009 and 2010 had stalled.[157] The United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor claims in their 2012 report on human rights practices in the country that the most significant problems are corruption, lack of religious freedom, abuse, and unequal treatment of women.[158]

Administrative divisions

The Maldives has twenty-six natural atolls and few island groups on isolated reefs, all of which have been divided into twenty-one administrative divisions (17 administrative atolls and cities of Malé, Addu, Fuvahmulah, Thinadhoo, and Kulhudhuffushi).[159]

Each atoll is administered by an elected Atoll Council. The islands are administered by an elected Island Council.

In addition to a name, every administrative division is identified by the Maldivian code letters, such as "Haa Alif" for Thiladhunmati Uthuruburi (Thiladhunmathi North); and by a Latin code letter. The first corresponds to the geographical Maldivian name of the atoll; the second is a code adopted for convenience. As certain islands in different atolls have the same name, for administrative purposes this code is quoted before the name of the island, for example: Baa Funadhoo, Kaafu Funadhoo, Gaafu-Alifu Funadhoo. Since most atolls have very long geographical names it is also used whenever the long name is inconvenient, for example in the atoll website names.[160]

The introduction of code-letter names has been a source of much puzzlement and misunderstanding, especially among foreigners. Many people have come to think that the code letter of the administrative atoll is its new name and that it has replaced its geographical name. Under such circumstances, it is hard to know which is the correct name to use.[160]

Remove ads

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

Historically, the Maldives provided enormous quantities of cowry shells, an international currency of the early ages. From the 2nd century CE, the islands were known as the 'Money Isles' by the Arabs.[161] Monetaria moneta was used for centuries as a currency in Africa, and huge amounts of Maldivian cowries were introduced into Africa by western nations during the period of slave trade.[162] The cowry is now the symbol of the Maldives Monetary Authority.

In the early 1970s and 1980s, the Maldives was one of the world's 20 poorest countries, with a population of 100,000.[163] The economy at the time was largely dependent on fisheries and trading local goods such as coir rope, ambergris (Maavaharu), and coco de mer (Tavakkaashi) with neighbouring countries and East Asian countries.[164]

The Maldivian government began a largely successful economic reform programme in the 1980s, initiated by lifting import quotas and giving more opportunities to the private sector. At that time, the tourism sector was in its infant stage but would later play a significant role in the nation's development. Agriculture and manufacturing continue to play lesser roles in the economy, constrained by the limited availability of cultivable land and the shortage of domestic labour.

Tourism

The Maldives remained largely unknown to tourists until the early 1970s. Only 200 islands are home to its 382,751 inhabitants.[165][166] The other islands are used entirely for economic purposes, of which tourism and agriculture are the most dominant. Tourism accounts for 28% of the GDP and more than 60% of the Maldives' foreign exchange receipts. Over 90% of government tax revenue comes from import duties and tourism-related taxes.

The development of tourism fostered the overall growth of the country's economy. It created direct and indirect employment and income generation opportunities in other related industries. The first tourist resorts were opened in 1972 with Bandos Island Resort and Kurumba Village (the current name is Kurumba Maldives),[167] which transformed the Maldives' economy.

According to the Ministry of Tourism, the emergence of tourism in 1972 transformed the economy, moving rapidly from dependence on fisheries to tourism. In just three and a half decades, the industry became the main source of income. Tourism was also the country's biggest foreign currency earner and the single largest contributor to the GDP. As of 2008[update], 89 resorts in the Maldives offered over 17,000 beds and hosted over 600,000 tourists annually.[168] In 2019, over 1.7 million visitors came to the islands.[169]

The number of resorts increased from 2 to 92 between 1972 and 2007. As of 2007[update], over 8,380,000 tourists had visited the Maldives.[170]

The country has six heritage Maldivian coral mosques listed as UNESCO tentative sites.[171]

Visitors

Visitors to the Maldives do not need to apply for a visa pre-arrival, regardless of their country of origin, provided they have a passport with at least 1 month validity, a complete travel itinerary (including return journey confirmed tickets, prepaid confirmed booking at a registered facility,[172] proof of financial means for sufficient funds to support the stay in Maldives, and entry requirements for their onward destinations—such as visa and passport validity), a Traveller Declaration form (which must be filled out and submitted by all foreigners arriving in the Maldives within 96 hours of the flight), and a Yellow Fever Vaccination Certificate, if applicable.[173] However, entry is denied to Israeli passports.[174]

Most visitors arrive at Velana International Airport, on Hulhulé Island, adjacent to the capital Malé. The airport is served by flights to and from India, Sri Lanka, Doha, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Singapore, Dhaka, Istanbul, and major airports in South-East Asia like Kuala Lumpur International in Malaysia, as well as charters from Europe like Charles De Gaulle in France. Gan Airport, on the southern atoll of Addu, also serves an international flight to Malpensa in Milan several times a week. British Airways offers direct flights to the Maldives from Heathrow Airport.[175]

Fishing industry

For many centuries the Maldivian economy was entirely dependent on fishing and other marine products. Fishing remains the main occupation of the people and the government gives priority to the fisheries sector.

The mechanisation of the traditional fishing boat called dhoni in 1974 was a major milestone in the development of the fisheries industry. A fish canning plant was installed on Felivaru in 1977, as a joint venture with a Japanese firm. In 1979, a Fisheries Advisory Board was set up with the mandate of advising the government on policy guidelines for the overall development of the fisheries sector. Manpower development programmes began in the early 1980s, and fisheries education was incorporated into the school curriculum. Fish aggregating devices and navigational aids were located at various strategic points. Moreover, the opening up of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the Maldives for fisheries has further enhanced the growth of the fisheries sector.

As of 2010[update], fisheries contributed over 15% of the country's GDP and engaged about 30% of the country's workforce. Fisheries were also the second-largest foreign exchange earner after tourism.

Remove ads

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

The largest ethnic group is Dhivehin, i.e. the Maldivians, native to the historic region of the Maldive Islands comprising today's Republic of Maldives and the island of Minicoy in Union territory of Lakshadweep, India. They share the same culture and speak the Dhivehi language. They are principally an Indo-Aryan people, having traces of Middle Eastern, South Asian, Austronesian and African genes in the population.

In the past, there was also a small Tamil population known as the Giraavaru people. This group has now been almost completely absorbed into the larger Maldivian society but was once native to the island of Giraavaru, which was evacuated in 1968 due to heavy erosion of the island.[178]

There is a small Sinhalese population in the Maldives where they made up 0.7% of the total population in 2000.[179]

Some social stratification exists on the islands. It is not rigid, since rank is based on varied factors, including occupation, wealth, Islamic virtue, and family ties. Instead of a complex caste system, there was merely a distinction between noble (bēfulhu) and common people in the Maldives. Members of the social elite are concentrated in Malé.

The population doubled by 1978, and the population growth rate peaked at 3.4% in 1985. By the 2006 census, the population had reached 298,968,[180] although the census in 2000 showed that the population growth rate had declined to 1.9%. Life expectancy at birth stood at 46 years in 1978, and later rose to 72. Infant mortality has declined from 12.7% in 1977 to 1.2% today, and adult literacy reached 99%. Combined school enrolment reached the high 90s. The population was projected to have reached 317,280 in 2010.[181]

The 2014 Population and Housing Census listed the total population in the Maldives as 437,535: 339,761 resident Maldivians and 97,774 resident foreigners, approximately 16% of the total population. However, it is believed that foreigners have been undercounted.[177][182] As of May 2021[update], there were 281,000 expatriate workers, an estimated 63,000 of whom are undocumented in the Maldives: 3,506 Chinese, 5,029 Nepalese, 15,670 Sri Lankans, 28,840 Indians, and (the largest group of foreigners working in the country) 112,588 Bangladeshis.[183][184][185] Other immigrants include Filipinos as well as various Western foreign workers.

Religion

After the long Buddhist period of Maldivian history,[186] Muslim traders introduced Islam. Maldivians converted to Islam by the mid-12th century. The islands have had a long history of Sufic orders, as can be seen in the history of the country such as the building of tombs. They were used until as recently as the 1980s for seeking the help of buried saints. They can be seen next to some old mosques and are considered a part of the Maldives's cultural heritage.

Other aspects of tassawuf, such as ritualised dhikr ceremonies called Maulūdu (Mawlid) – the liturgy of which included recitations and certain supplications in a melodic tone – existed until very recent times. These Maulūdu festivals were held in ornate tents specially built for the occasion. At present Islam is the official religion of the entire population, as adherence to it is required for citizenship.

According to Arab traveller Ibn Battuta, the person responsible for this conversion was a Sunni Muslim visitor named Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari, sailing from what is today Morocco. He is also referred to as Tabrizugefaanu. His venerated tomb now stands on the grounds of Medhu Ziyaaraiy, across the street from the Friday Mosque, or Hukuru Miskiy, in Malé. Originally built in 1153 and re-built in 1658,[52] this is one of the country's oldest surviving mosques.

In 2013, scholar Felix Wilfred of Oxford University estimated the number of Christians in Maldives as 1,400 or 0.4% of the country's population.[187]

Since the adoption of the 2008 constitution citizens and anyone wishing to become citizens is required by law to nominally follow Sunni Islam[188] which would make Maldives a 100% Muslim country in theory. But residents, tourists, and guest workers are free to be of any religion and practise them in private. However, in 2020, studies found that 0.29% of the population is Christian (roughly split between Catholic and Protestant).[189]

Languages

The official and national language is Dhivehi, an Indo-Aryan language closely related to the Sinhala language of Sri Lanka. The first known script used to write Dhivehi is the eveyla akuru script, which is found in the historical recording of kings (raadhavalhi). Later a script called Dhives Akuru was used for a long period. The present-day script is called Thaana and is written from right to left. Thaana is derived from a mix of the old indigenous script of Dhives Akuru and Arabic abjad. Thaana is said to have been introduced during the reign of Mohamed Thakurufaanu.

English is widely spoken by the locals of the Maldives:[190] "Following the nation's opening to the outside world, the introduction of English as a medium of instruction at the secondary and tertiary levels of education, and its government's recognition of the opportunities offered through tourism, English has now firmly established itself in the country. As such, the Maldives are quite similar to the countries in the Gulf region... The nation is undergoing vast societal change, and English is part of this."[191]

Otherwise, Arabic is taught in schools and mosques, as Sunni Islam is the state religion. The Maldivian population has formal or informal education in the reading, writing, and pronunciation of the Arabic language, as part of the compulsory religious education for all primary and secondary school students.[188]

Thikijehi Thaana

These additional letters were added to the Thaana alphabet by adding dots (nukuthaa) to existing letters, to allow for transliteration of Arabic loanwords, as previously Arabic loanwords were written using the Arabic script. Their usage is inconsistent, and becoming less frequent as the spelling changes to reflect pronunciation by Maldivians, rather than the original Arabic pronunciation, as the words get absorbed into the Maldivian language.

Population by locality

Health

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative reports that Maldives is meeting 5.1 out of 10 of the expected fulfilment for the right to health considering its income level.[192] Specifically for children's health rights, Maldives attains 98.0% of the anticipated level based on its current income.[192] Regarding adult health rights, the country achieves 99.7% of the expected fulfilment considering its income level. However, in terms of reproductive health rights, Maldives falls into the "very bad" category, as it fulfills only 18.2% of the expected achievement based on its available resources.[193]

Life expectancy at birth in Maldives was 77 years in 2011.[194] Infant mortality fell from 34 per 1,000 in 1990 to 15 in 2004. There is an increasing disparity between health in the capital and on the other islands. There is also a problem of malnutrition. Imported food is expensive.[195]

On 24 May 2021, the Maldives had the world's fastest-growing COVID-19 outbreak, with the highest number of infections per million people over the prior 7 and 14 days, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.[196] Doctors warned that increasing demand for COVID-19 care could hinder their ability to handle other health emergencies in the Maldives.[197] The reason for the outbreak was the Delta variant.

Transportation

Velana International Airport is the principal gateway to the Maldives; it is adjacent to the capital city Malé and is connected by Sinamalé Bridge. International travel is available on government-owned Island Aviation Services (branded as Maldivian), which operates DHC-6 Twin Otter seaplanes and to nearly all Maldivian domestic airports with several Bombardier Dash 8 aircraft, and one Airbus A320 with international service to India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Thailand, and China.

In the Maldives, there are three main ways to travel between islands: by domestic flight, by seaplane, or by boat.[198] For several years two seaplane companies were operating: TMA (Trans Maldivian Airways) and Maldivian Air Taxi, but these merged in 2013 under the name TMA. The seaplane fleet is entirely made up of DHC-6 Twin Otters. There is also another airline, Villa Air, which operates using ATR planes to domestic airports, principally Villa-Maamigili, Dharavandhoo and some others. Manta Air began its first scheduled seaplane service in 2019. Its seaplane fleet is made up of DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft. In addition to the seaplane service, Manta Air uses ATR 72–600 aircraft to operate domestic flights to Dhaalu Airport, Dharavandhoo Airport and Kooddoo Airport from the main Velana International Airport.[199] Depending on the distance of the destination island from the airport, resorts organise speedboat transfers or seaplane flights directly to the resort island jetty for their guests. Several daily flights operate from Velana International Airport to the 18 domestic and international airports in the country. Scheduled ferries also operate from Malé to many of the atolls. The traditional Maldivian boat is called a dhoni, one of the oldest known sea vessels in the Maldives.[200] Speedboats and seaplanes tend to be more expensive, while travel by dhoni, although slower, is relatively cheaper and convenient.

Education

The Maldives National University is one of the country's institutions of higher education.[g][201] In 1973, the Allied Health Services Training Centre (the forerunner of the Faculty of Health Sciences) was established by the Ministry of Health.[202] The Vocational Training Centre was established in 1974, providing training for mechanical and electrical trades.[203] In 1984, the Institute for Teacher Education was created and the School of Hotel and Catering Services was established in 1987 to provide trained personnel for the tourist industry.[204] In 1991, the Institute of Management and Administration was created to train staff for public and private services. In 1998, the Maldives College of Higher Education was founded. The Institute of Shar'ah and Law was founded in January 1999. In 2000 the college launched its first-degree programme, Bachelor of Arts. On 17 January 2011, the Maldives National University Act was passed by the President of the Maldives; The Maldives National University was named on 15 February 2011. In 2015 under a Presidential decree the College of Islamic Studies was changed into the Islamic University of Maldives (IUM).[205]

The Maldivian government now offers 3 different scholarships to students who have completed their higher secondary education with results above a certain threshold, with ranks of the scholarship received depending on the merits achieved by students on their year 12 examinations.[206]

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

The culture of the Maldives is influenced by the cultures of the people of different ethnicities who have settled on the islands throughout the times.

Since the 12th century AD, there were also influences from Arabia in the language and culture of the Maldives because of the conversion to Islam and its location as a crossroads in the central Indian Ocean.[207] This was due to the long trading history between the far east and the middle east.

Reflective of this is the fact that the Maldives has had the highest national divorce rate in the world for many decades. This, it is hypothesised, is due to a combination of liberal Islamic rules about divorce and the relatively loose marital bonds that have been identified as common in non- and semi-sedentary peoples without a history of fully developed agrarian property and kinship relations.[208]

Media

PSM news serves as the country's main media, owned by the government of the Maldives.[209] The newspaper was founded on 3 May 2017, in the celebration of World Press Freedom Day.[210] Maldives has been ranked one–hundred in the World Press Freedom Index 2023 and 106 in 2024.[211] The country's first daily newspaper, Haveeru Daily News was the first and longest–serving newspaper in the history of the Maldives, which was registered on 28 December 1978, and dissolved in 2016.[212] Article 28 of the Maldives Constitution guarantees freedom of the press and stipulates that:

No person shall be compelled to disclose the source of any information that is espoused, disseminated, or published by that person.[213]

However, this protection is compromised by the Evidence Act, which came into effect in January 2023 and grants courts the authority to compel journalists to reveal their confidential sources. The Maldives Media Council (MMC) and the Maldives Journalists Association (MJA) serve as crucial watchdogs in addressing and combating these threats. Newspapers Sun Online, Mihaaru and its English edition named The Edition, and Avas serve as well–known private news outlets.[214]

Sports

Sports are deeply ingrained in the culture of the Maldives, with various activities based on traditional pastimes and modern sporting pursuits. Given its geography of scattered islands surrounded by the Indian Ocean, water sports naturally hold a prominent position. Surfing, in particular, has gained international recognition. Locations such as the atolls of North and South Malé, Thulusdhoo, and Himmafushi offer ideal surfing conditions.[215] Additionally, diving and snorkelling are immensely popular.[216]

Football, or soccer, is one of the most widely-played and passionately-followed sports in the Maldives.[217] The Maldives national football team competes in regional and international tournaments. The country has its own domestic football league, the Dhivehi Premier League, featuring clubs from various atolls vying for supremacy.[218] Matches often draw large crowds. Futsal is also popular, especially among younger generations, with numerous indoor facilities providing spaces for friendly matches and competitive leagues.

Bodu Beru, a rhythmic drumming and dance performance, often accompanies events for traditional sports such as "Baibalaa", a game resembling volleyball but played with a woven ball made from dried coconut palm leaves, and "Fenei Bashi", a form of wrestling.

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- The total area, including its exclusive economic zone territory is approximately 89,999 square kilometres, behind Jordan (89,342 square kilometres) and ahead of Portugal (92,220 square kilometres). With the EEZ, the Maldives would be the 110th largest country.[2]

- /ˈmɔːldivz/ ⓘ MAWL-deevz; Dhivehi: ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, romanized: Dhivehi Raajje, pronounced [diʋehi ɾaːd͡ʒːe].

- ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, pronounced [diʋehi ɾaːd͡ʒːeːge d͡ʒumhuːɾijjaː].

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads