Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Max Planck Society

Association of German research institutes From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

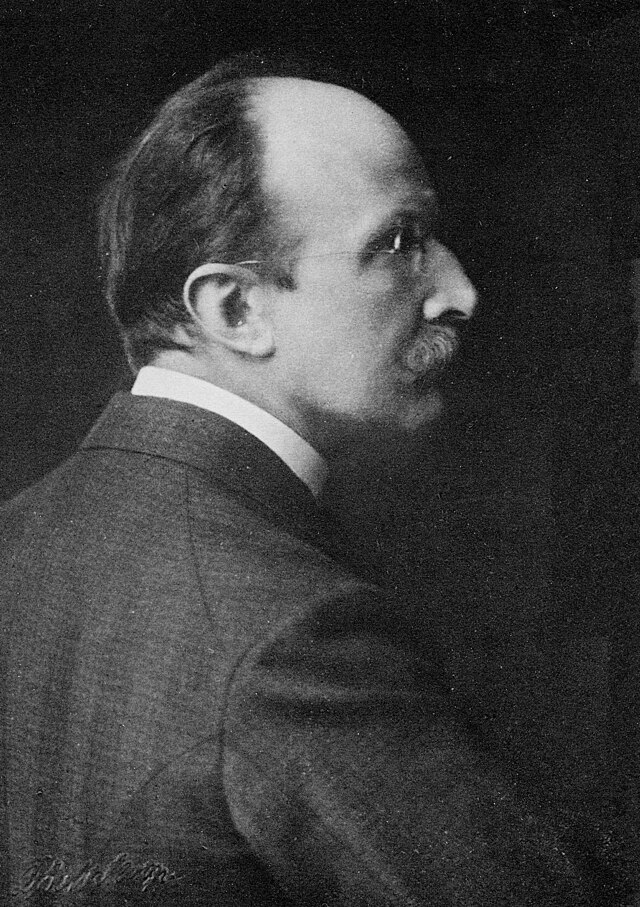

The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science (German: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e. V.; MPG) is a formally independent non-governmental and non-profit association of German research institutes. Founded in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society,[1][3] it was renamed to the Max Planck Society in 1948 in honor of its former president, theoretical physicist Max Planck. The society is funded by the federal and state governments of Germany.[2][1]

Remove ads

Mission

Summarize

Perspective

According to its primary goal, the Max Planck Society supports fundamental research in the natural, life and social sciences, the arts and humanities in its 84 (as of January 2024)[2] institutes and research facilities.[1][3] As of 31 December 2023[update], the society has a total staff of 24,655 permanent employees, including 6,688 contractually employed scientists, 3,444 doctoral candidates, and 3,203 guest scientists.[2] 44.9% of all employees are female and 57.2% of the scientists are foreign nationals. The society's budget for 2023 was about €2.1 billion.[2]

The Max Planck Society has a world-leading reputation as a science and technology research organization, with 39 Nobel Prizes awarded to their scientists, and is widely regarded as one of the foremost basic research organizations in the world. In 2020, the Nature Index placed the Max Planck Institutes third worldwide in terms of research published in Nature journals (after the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Harvard University).[4] In terms of total research volume (unweighted by citations or impact), the Max Planck Society is only outranked by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Russian Academy of Sciences and Harvard University in the Times Higher Education institutional rankings.[5] The Thomson Reuters-Science Watch website placed the Max Planck Society as the second leading research organization worldwide following Harvard University in terms of the impact of the produced research over science fields.[6]

The Max Planck Society and its predecessor Kaiser Wilhelm Society hosted several renowned scientists in their fields, including Otto Hahn, Werner Heisenberg, and Albert Einstein.

The Max Planck Society also hosts the Cornell, Maryland, and Max Planck Pre-Doctoral Research School, an intense week of lectures, informal conversations with guest faculty and fellow students from all over the world, professional development panels with academic and industrial speakers, research poster sessions, and social events.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The organization was established in 1911 as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, or Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft (KWG), a non-governmental research organization named for the then German emperor. The KWG was one of the world's leading research organizations; its board of directors included scientists like Walther Bothe, Peter Debye, Albert Einstein, and Fritz Haber. In 1946, Otto Hahn assumed the position of president of KWG, and in 1948, the society was renamed the Max Planck Society (MPG) after its former president (1930–37) Max Planck, who died in 1947.[7]

The Max Planck Society has a world-leading reputation as a science and technology research organization. In 2006, the Times Higher Education Supplement rankings[8] of non-university research institutions (based on international peer review by academics) placed the Max Planck Society as No.1 in the world for science research, and No.3 in technology research (behind AT&T Corporation and the Argonne National Laboratory in the United States).

The domain mpg.de attracted at least 1.7 million visitors annually by 2008 according to a Compete.com study.[9]

List of presidents of the KWG and the MPG

- Adolf von Harnack (1911–1930)

- Max Planck (1930–1937)

- Carl Bosch (1937–1940)

- Albert Vögler (1941–1945)

- Max Planck (16 May 1945 – 31 March 1946)

- Otto Hahn (as President of the KWG 1946 and then as Founder and President of the MPG 1948–1960)

- Adolf Butenandt (1960–1972)

- Reimar Lüst (1972–1984)

- Heinz Staab (1984–1990)

- Hans F. Zacher (1990–1996)

- Hubert Markl (1996–2002)

- Peter Gruss (2002–2014)

- Martin Stratmann (2014–2023)

- Patrick Cramer (2023–present)

Remove ads

Max Planck Research Award

Summarize

Perspective

From 1990 to 2004, the "Max Planck Research Award for International Cooperation" was presented to several researchers from a wide range of disciplines each year.

From 2004 to 2017, the "Max Planck Research Award" was conferred annually to two internationally renowned scientists, one of whom was working in Germany and one in another country. Calls for nominations for the award were invited on an annually rotating basis in specific sub-areas of the natural sciences and engineering, the life sciences, and the human and social sciences. The objective of the Max Planck Society and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in presenting this joint research award was to give added momentum to specialist fields that were either not yet established in Germany or that deserved to be expanded.[10]

Since 2018, the award has been succeeded by the "Max Planck-Humboldt Research Award", annually awarded to an internationally renowned mid-career researcher with outstanding future potential from outside Germany but having a strong interest in a research residency in Germany for limited time periods, alternately in the fields of natural and engineering sciences, human sciences, and life sciences, as well as the "Max Planck-Humboldt Medal" awarded to other two finalists.[11][12][13][14]

Max Planck-Humboldt Research Awards and Medals

Max Planck Research Award

Remove ads

Organization

Summarize

Perspective

The Max Planck Society is formally an eingetragener Verein, a registered association with the institute directors as scientific members having equal voting rights.[15] The society has its registered seat in Berlin, while the administrative headquarters are located in Munich. Since June 2023, chemist and molecular biologist Patrick Cramer has been the President of the Max Planck Society.[16]

Funding is provided predominantly from federal and state sources, but also from research and license fees and donations. One of the larger donations was the castle Schloss Ringberg near Kreuth in Bavaria, which was pledged by Luitpold Emanuel in Bayern (Duke in Bavaria). It passed to the Society after the duke died in 1973, and is now used for conferences.

Max Planck Institutes and research groups

The Max Planck Society consists of over 80 research institutes.[17] In addition, the society funds a number of Max Planck Research Groups (MPRG) and International Max Planck Research Schools (IMPRS). The purpose of establishing independent research groups at various universities is to strengthen the required networking between universities and institutes of the Max Planck Society.

The research units are primarily located across Europe with a few in South Korea and the U.S. In 2007, the Society established its first non-European centre, with an institute on the Jupiter campus of Florida Atlantic University focusing on neuroscience.[18][19]

The Max Planck Institutes operate independently from, though in close cooperation with, the universities, and focus on innovative research that does not fit into the university structure due to its interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary nature or that require resources that cannot be met by the state universities.

Internally, Max Planck Institutes are organized into research departments headed by directors such that each MPI has several directors, a position roughly comparable to anything from full professor to department head at a university. Other core members include Junior and Senior Research Fellows.[20]

In addition, there are several associated institutes:[17]

Max Planck Society also has a collaborative center with Princeton University—Max Planck Princeton Research Center for Plasma Physics—located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the U.S.[21] The latest Max Planck Research Center has been established at Harvard University in 2016 as the Max Planck Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean.

International Max Planck Research Schools

Together with the Association of Universities and other Education Institutions in Germany, the Max Planck Society established numerous International Max Planck Research Schools (IMPRS) to promote junior scientists:

- Cologne Graduate School of Ageing Research, Cologne[22]

- Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics

- International Max Planck Research School for Intelligent Systems, at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems located in Tübingen and Stuttgart[23]

- International Max Planck Research School on Adapting Behavior in a Fundamentally Uncertain World (Uncertainty School), at the Max Planck Institutes for Economics, for Human Development, and/or Research on Collective Goods

- International Max Planck Research School for Analysis, Design and Optimization in Chemical and Biochemical Process Engineering, Magdeburg[24]

- International Max Planck Research School for Astronomy and Cosmic Physics, Heidelberg at the MPI for Astronomy

- International Max Planck Research School for Astrophysics, Garching at the MPI for Astrophysics

- International Max Planck Research School for Complex Surfaces in Material Sciences, Berlin[25]

- International Max Planck Research School for Computer Science, Saarbrücken[26]

- International Max Planck Research School for Earth System Modeling, Hamburg[27]

- International Max Planck Research School for Elementary Particle Physics, Munich, at the MPI for Physics[28]

- International Max Planck Research School for Environmental, Cellular and Molecular Microbiology, Marburg at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology

- International Max Planck Research School for Evolutionary Biology, Plön at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology[29]

- International Max Planck Research School "From Molecules to Organisms", Tübingen at the Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen[30]

- International Max Planck Research School for Global Biogeochemical Cycles, Jena at the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry[31]

- International Max Planck Research School on Gravitational Wave Astronomy, Hannover and Potsdam MPI for Gravitational Physics[32]

- International Max Planck Research School for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research[33]

- International Max Planck Research School for Infectious Diseases and Immunity, Berlin at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology[34][35]

- International Max Planck Research School for Language Sciences, Nijmegen[36]

- International Max Planck Research School for Neurosciences, Göttingen[37]

- International Max Planck Research School for Cognitive and Systems Neuroscience, Tübingen[38]

- International Max Planck Research School for Marine Microbiology (MarMic), joint program of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, the University of Bremen, the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, and the Jacobs University Bremen[39]

- International Max Planck Research School for Maritime Affairs, Hamburg[40]

- International Max Planck Research School for Molecular and Cellular Biology, Freiburg

- International Max Planck Research School for Molecular and Cellular Life Sciences, Munich[41]

- International Max Planck Research School for Molecular Biology, Göttingen[42]

- International Max Planck Research School for Molecular Cell Biology and Bioengineering, Dresden[43]

- International Max Planck Research School Molecular Biomedicine, program combined with the 'Graduate Programm Cell Dynamics And Disease' at the University of Münster and the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine[44]

- International Max Planck Research School on Multiscale Bio-Systems, Potsdam[45]

- International Max Planck Research School for Organismal Biology, at the University of Konstanz and the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology[46][47]

- International Max Planck Research School on Reactive Structure Analysis for Chemical Reactions (IMPRS RECHARGE), Mülheim an der Ruhr, at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion[48]

- International Max Planck Research School for Science and Technology of Nano-Systems, Halle at Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics

- International Max Planck Research School for Solar System Science[49] at the University of Göttingen[50] hosted by MPI for Solar System Research[51]

- International Max Planck Research School for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Bonn, at the MPI for Radio Astronomy (formerly the International Max Planck Research School for Radio and Infrared Astronomy)[52]

- International Max Planck Research School for the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy, Cologne[53]

- International Max Planck Research School for Surface and Interface Engineering in Advanced Materials, Düsseldorf at Max Planck Institute for Iron Research GmbH

- International Max Planck Research School for Ultrafast Imaging and Structural Dynamics, Hamburg[54]

Max Planck Schools

Max Planck Center

Max Planck Institutes

Among others:

- Kunsthistorische Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, Florence, Italy

- Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience

- Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology of Behavior – caesar, Bonn

- Max Planck Institute for Aeronomics in Katlenburg-Lindau was renamed to Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in 2004;

- Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen in Tübingen;

- Max Planck Institute for Cell Biology in Ladenburg b. Heidelberg was closed in 2003;

- Max Planck Institute for Economics in Jena was renamed to the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in 2014;

- Max Planck Institute for Ionospheric Research in Katlenburg-Lindau was renamed to Max Planck Institute for Aeronomics in 1958;

- Max Planck Institute for Metals Research, Stuttgart

- Max Planck Institute of Oceanic Biology in Wilhelmshaven was renamed to Max Planck Institute of Cell Biology in 1968 and moved to Ladenburg 1977;

- Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research in Munich merged into the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in 2004;

- Max Planck Institute for Protein and Leather Research in Regensburg moved to Munich 1957 and was united with the Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry in 1977;

- Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World in Starnberg (from 1970 until 1981 (closed)) directed by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Jürgen Habermas.

- Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology

- Max Planck Institute of Experimental Endocrinology

- Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Social Law

- Max Planck Institute for Physics and Astrophysics

- Max Planck Research Unit for Enzymology of Protein Folding

- Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Potsdam

- Max Planck Institute for Coal Research in Mülheim

Remove ads

Open access publishing

Summarize

Perspective

The Max Planck Society describes itself as "a co-founder of the international Open Access movement".[58] Together with the European Cultural Heritage Online Project the Max Planck Society organized the Berlin Open Access Conference in October 2003 to ratify the Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing. At the Conference the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities was passed. The Berlin Declaration built on previous open access declarations, but widened the research field to be covered by open access to include humanities and called for new activities to support open access such as "encouraging the holders of cultural heritage" to provide open access to their resources.[59]

The Max Planck Society continues to support open access in Germany and mandates institutional self-archiving of research outputs on the eDoc server and publications by its researchers in open access journals within 12 months.[60] To finance open access the Max Planck Society established the Max Planck Digital Library. The library also aims to improve the conditions for open access on behalf of all Max Planck Institutes by negotiating contracts with open access publishers and developing infrastructure projects, such as the Max Planck open access repository.[61]

Remove ads

Criticism

Summarize

Perspective

Pay for PhD students

In 2008, the European General Court ruled in a case brought by a PhD student against the Max Planck Society that "a researcher preparing a doctoral thesis on the basis of a grant contract concluded with the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften eV, must be regarded as a worker within the meaning of Article 39 EC only if his activities are performed for a certain period of time under the direction of an institute forming part of that association and if, in return for those activities, he receives remuneration".[62]

In 2012, the Max Planck Society was at the centre of a controversy about some PhD students not being given employment contracts. Of the 5,300 students who at the time wrote their PhD thesis at the 80 Max Planck Institutes 2,000 had an employment contract. The remaining 3,300 received grants of between 1,000 and 1,365 Euro.[63] According to a 2011 statement by the Max Planck Society "As you embark on a PhD, you are still anything but a proper scientist; it's during the process itself that you become a proper scientist... a PhD is an apprenticeship in the lab, and as such it is usually not paid like a proper job – and this is, by and large, the practice at all research institutions and universities".[64] The allegation of wage dumping for young scientists was discussed during the passing of the 2012 "Wissenschaftsfreiheitsgesetz" (Scientific Freedom Law) in the German Parliament.[65]

Freedom of expression

In February 2024, the Max Planck Society faced widespread criticism for terminating the employment of Lebanese-Australian professor Ghassan Hage from the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, citing his social media posts on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict as incompatible with the society's core values.[66] This decision was publicly condemned by numerous scholars and academic organizations, who argued it infringed on Hage's freedom of expression. German newspaper Welt am Sonntag initially reported on Hage's posts.[67][68] Following the dismissal, global academic communities, including Israeli scholars,[69] the German Association of Social and Cultural Anthropology,[70] the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies,[71] the European Association of Social Anthropologists,[72] the American Anthropological Association,[73] the Council for Humanities, Arts and Sciences and the Australian Anthropological Society,[74] the Canadian Anthropology Society,[75] a Japanese group of scholars,[76] the Australian Sociological Association,[77] rallied in support of Hage, extensively citing Hage's own intellectual work, urging the society to reverse its decision. The Max Planck Society and the President Patrick Cramer have not yet respond to these letters, as of July 2024.[78][79] The Max Planck Society has made public statements expressing support for the state of Israel in the Gaza war.[80][81] Hage filed a legal challenge contesting his dismissal. In December 2024, the Labour Court Halle rejected the dismissal claim of Ghassan Hage.[82]

Allegations of misconduct

Since at least 2018, there have been numerous accusations of bullying and harassment by senior researchers and directors at the Max Planck Society. In 2018, two high-profile cases of bullying were made public. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching accused director Guinevere Kauffmann of insulting and bullying students and making racist remarks.[83][84] Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences also accused director Tania Singer of bullying and intimidation.[85] As of April 2025, both remain at the Max Planck Society.[86][87]

In 2021, Nicole Boivin, a director of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (renamed the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology in 2022), was removed after an internal investigation by the Max Planck Society reportedly determined that she had bullied junior researchers and plagiarized their work, along with other accusations. In December 2021, a court ruling reinstated her as a director. However in April 2022, she was removed following a vote by a governing board of the Max Planck Society.[88] However, as of April 2025, she is still employed as a Research Group Leader.[89] The same year, ecologist Ian Baldwin, a director at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, was accused of harassing doctoral candidates and postdoctoral researchers.[90]

In March 2025, a joint investigation between Deutsche Welle and Der Spiegel concluded that within the Max Planck Society, there was "a systemic failure to hold abusive staff members or their institutes accountable". Interviews with over 30 scientists, many recruited internationally, revealed that more than half experienced or witnessed misconduct by senior staff, particularly directors and group leaders. Women and people of color were identified as being at higher risk of such abuse. Many of those interviewed within the report wished to remain anonymous to avoid retaliation. Specific allegations of misconduct against Jan-Michael Rost, director of the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems in Dresden, were highlighted within the report.[91][92]

Remove ads

Nobel Laureates

Kaiser Wilhelm Society (1914–1948)

- Max von Laue, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914

- Richard Willstätter, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1915

- Fritz Haber, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918

- Max Planck, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918

- Albert Einstein, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921

- Otto Meyerhof, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1922

- James Franck, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1925

- Carl Bosch, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931

- Otto Heinrich Warburg, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1931

- Werner Heisenberg, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932

- Hans Spemann, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1935

- Peter J. W. Debye, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1936

- Richard Kuhn, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1938

- Adolf Butenandt, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1939

- Otto Hahn, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944

Max Planck Society (since 1948)

- Walter Bothe, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1954

- Karl Ziegler, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1963

- Feodor Lynen, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1964

- Manfred Eigen, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1967

- Konrad Lorenz, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973

- Georges Köhler, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984

- Klaus von Klitzing, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1985

- Ernst Ruska, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986

- Johann Deisenhofer, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1988

- Hartmut Michel, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1988

- Robert Huber, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1988

- Bert Sakmann, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1991

- Erwin Neher, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1991

- Paul Crutzen, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995

- Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995

- Theodor W. Hänsch, Nobel Prize in Physics in 2005

- Gerhard Ertl, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2007

- Stefan W. Hell, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2014

- Reinhard Genzel, Nobel Prize in Physics in 2020

- Emmanuelle Charpentier, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020

- Klaus Hasselmann, Nobel Prize in Physics in 2021

- Benjamin List, Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2021

- Svante Pääbo, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2022

- Ferenc Krausz, Nobel Prize in Physics in 2023

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads