Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Paradise Lost

Epic poem by John Milton From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

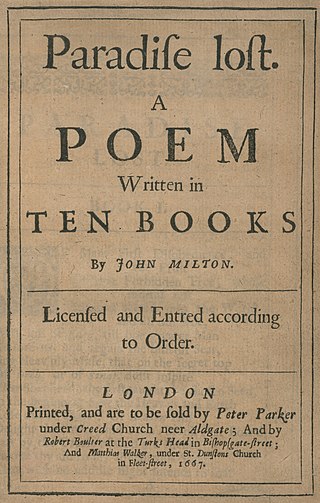

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 1674, arranged into twelve books (in the manner of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout.[1][2] It is considered to be Milton's masterpiece, and it helped solidify his reputation as one of the greatest English poets of all time.[3]

At the heart of Paradise Lost are the themes of free will and the moral consequences of disobedience. Milton seeks to "justify the ways of God to men," addressing questions of predestination, human agency, and the nature of good and evil. The poem begins in medias res, with Satan and his fallen angels cast into Hell after their failed rebellion against God. Milton's Satan, portrayed with both grandeur and tragic ambition, is one of the most complex and debated characters in literary history, particularly for his perceived heroism by some readers.

The poem's portrayal of Adam and Eve emphasizes their humanity, exploring their innocence, before the Fall of Man, as well as their subsequent awareness of sin. Through their story, Milton reflects on the complexities of human relationships, the tension between individual freedom and obedience to divine law, and the possibility of redemption. Despite their transgression, the poem ends on a note of hope, as Adam and Eve leave Paradise with the promise of salvation through Christ.

Milton's epic has been praised for its linguistic richness, theological depth, and philosophical ambition. However, it has also sparked controversy, particularly for its portrayal of Satan, whom some readers interpret as a heroic or sympathetic figure. Paradise Lost continues to inspire scholars, writers, and artists, remaining a cornerstone of literary and theological discourse.

Remove ads

Synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (lit. 'in the midst of things'), the background story being recounted later.

Milton's story has two narrative arcs, one about Satan (Lucifer) and the other about Adam and Eve. It begins after Satan and the other fallen angels have been defeated and banished to Hell, or, as it is also called in the poem, Tartarus. In Pandæmonium, the capital city of Hell, Satan employs his rhetorical skill to organise his followers; he is aided by Mammon and Beelzebub; Belial, Chemosh, and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers to corrupt the newly created Earth and God's new and most favoured creation, Mankind. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone, in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas. After an arduous traversal of the Chaos outside Hell, he enters God's new material World, and later the Garden of Eden.

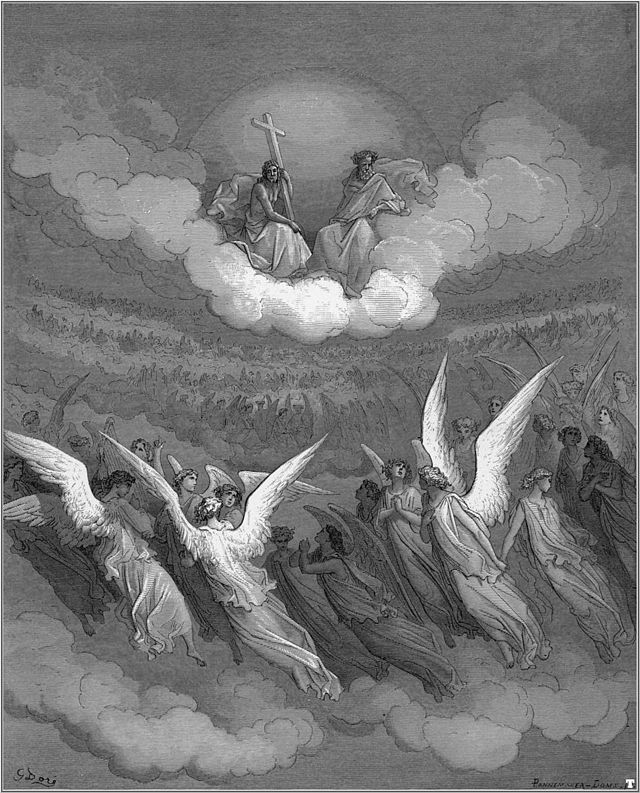

At several points in the poem, an Angelic War over Heaven is recounted from different perspectives. Satan's rebellion follows the epic convention of large-scale warfare. The battles between the faithful angels and Satan's forces take place over three days. At the final battle, the Son of God single-handedly defeats the entire legion of angelic rebels and banishes them from Heaven. Following this purge, God creates the World, culminating in his creation of Adam and Eve. While God gave Adam and Eve total freedom and power to rule over all creation, he gave them one explicit command: not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil on penalty of death. It is less often related that God was afraid that they would eat the fruit of the tree of life, and live forever.

Adam and Eve are presented as having a romantic and sexual relationship while still being without sin. They have passions and distinct personalities. Satan, disguised in the form of a serpent, successfully tempts Eve to eat from the Tree by preying on her vanity and tricking her with rhetoric. Adam, learning that Eve has sinned, knowingly commits the same sin. He declares to Eve that since she was made from his flesh, they are bound to one another – if she dies, he must also die. In this manner, Milton portrays Adam as a heroic figure, but also as a greater sinner than Eve, as he is aware that what he is doing is wrong.

After eating the fruit, Adam and Eve experience lust for the first time, which renders their next sexual encounter with one another unpleasant. At first, Adam is convinced that Eve was right in thinking that eating the fruit would be beneficial. However, they soon fall asleep and have terrible nightmares, and after they awake, they experience guilt and shame for the first time. Realising that they have committed a terrible act against God, they engage in mutual recrimination.

Meanwhile, Satan returns triumphantly to Hell, amid the praise of his fellow fallen angels. He tells them about how their scheme worked and Mankind has fallen, giving them complete dominion over Paradise. As he finishes his speech, however, the fallen angels around him become hideous snakes, and soon enough, Satan himself turns into a snake, deprived of limbs and unable to talk. Thus, they share the same punishment, as they shared the same guilt.

Eve appeals to Adam for reconciliation of their actions. Her encouragement enables them to approach God, and plead for forgiveness. In a vision shown to him by the Archangel Michael, Adam witnesses everything that will happen to Mankind until the Great Flood. Adam is very upset by this vision of the future, so Michael also tells him about Mankind's potential redemption from original sin through Jesus Christ (whom Michael calls "King Messiah"). Adam and Eve are cast out of Eden, and Michael says that Adam may find "a paradise within thee, happier far". Adam and Eve now have a more distant relationship with God, who is omnipresent but invisible (unlike the tangible Father in the Garden of Eden).

Remove ads

Composition

Summarize

Perspective

It is uncertain when Milton composed Paradise Lost.[4] John Aubrey (1626–1697), Milton's contemporary and biographer, says that it was written between 1658 and 1663.[5] However, parts of the poem had likely been in development since Milton was young.[5] Having gone blind in 1652, Milton wrote Paradise Lost entirely through dictation with the help of amanuenses and friends. He was often ill, suffering from gout, and suffering emotionally after the early death of his second wife, Katherine Woodcock, in 1658, and their infant daughter.[6] The image of Milton dictating the poem to his daughters became a popular subject for paintings, especially in the Romantic period.[7]

The Milton scholar John Leonard also notes that Milton "did not at first plan to write a biblical epic".[5] Since epics were typically written about heroic kings and queens (and with pagan gods), Milton originally envisioned his epic to be based on a legendary Saxon or British king like the legend of King Arthur.[8][9] Leonard speculates that the English Civil War interrupted Milton's earliest attempts to start his "epic [poem] that would encompass all space and time".[5]

Publication

In the 1667 version of Paradise Lost, the poem was divided into ten books. However, in the 1674 edition, the text was reorganized into twelve books.[10] In later printing, "Arguments" (brief summaries) were inserted at the beginning of each book.[11] Milton's previous work had been printed by Matthew Simmons who was favoured by radical writers. However, he died in 1654 and the business was then run by Mary Simmons. Milton had not published work with the Simmons printing business for twenty years. Mary was increasingly relying on her son Samuel to help her manage the business and the first book that Samuel Simmons registered for publication in his name was Paradise Lost in 1667.[12]

Remove ads

Style

Summarize

Perspective

Biblical epic

Key to the ambitions of Paradise Lost as a poem is the creation of a new kind of epic, one suitable for English, Christian morality rather than polytheistic Greek or Roman antiquity. This intention is indicated from the very beginning of the poem, when Milton uses the classical epic poetic device of an invocation for poetic inspiration. Rather than invoking the classical muses, however, Milton addresses the Christian God as his "Heav'nly Muse" (1.1). Other classical epic conventions include an in medias res opening, a journey in the underworld, large-scale battles, and an elevated poetic style. In particular, the poem often uses Homeric similes. Milton repurposes these epic conventions to create a new biblical epic, promoting a different kind of hero. Classical epic heroes like Achilles, Odysseus, and Aeneas were presented in the Iliad, Odyssey, and Aeneid as heroes for their military strength and guile, which might go hand in hand with wrath, pride, or lust. Milton attributes these traits instead to Satan, and depicts the Son as heroic for his love, mercy, humility, and self-sacrifice. The poem itself therefore presents the value system of classical heroism as one which has been superseded by Christian virtue.[4]

Blank verse

The poem is written in blank verse, meaning the lines are metrically regular iambic pentameter but they do not rhyme. Milton used the flexibility of blank verse to support a high level of syntactic complexity. Although Milton was not the first to use blank verse, his use of it was very influential and he became known for the style. Blank verse was not much used in the non-dramatic poetry of the 17th century until Paradise Lost. Milton also wrote Paradise Regained (1671) and parts of Samson Agonistes (1671) in blank verse. Miltonic blank verse became the standard for those attempting to write English epics for centuries following the publication of Paradise Lost and his later poetry.[13]

When Miltonic verse became popular, Samuel Johnson mocked Milton for inspiring bad blank verse imitators.[14] Alexander Pope's final, incomplete work was intended to be written in the form,[15] and John Keats, who complained that he relied too heavily on Milton,[16] adopted and picked up various aspects of his poetry.

Acrostics

Milton used a number of acrostics in the poem. In Book 9, a verse describing the serpent which tempted Eve to eat the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden spells out "SATAN" (9.510), while elsewhere in the same book, Milton spells out "FFAALL" and "FALL" (9.333). Respectively, these probably represent the double fall of humanity embodied in Adam and Eve, as well as Satan's fall from Heaven.[17]

Remove ads

Characters

Summarize

Perspective

Satan

Satan, formerly called Lucifer, is the first major character introduced in the poem. He is a tragic figure who famously declares: "Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heaven" (1.263). He viewed God as a tyrannical figure and refused to be subjected to his reign.[18] Satan was able to accumulate an army of angels who were loyal to his cause. He strove to "set himself in Glory above his Peers," and the pair of "Rebel angels" worked alongside him.[19] Following his vain rebellion against God, he is cast out from Heaven and condemned to Hell. The rebellion stems from Satan's pride and envy, derived from God's proclamation that the Son of God was "anointed" as the savior (5.660-664ff). As a result, Satan "thought himself impaird," meaning that his envy caused him to perceive himself as being lessened through God's actions.[20]

Satan is also depicted as a persuasive and charismatic being, whose rhetorical skills allow him to manipulate others and rally the fallen angels. What makes him so effective is his ability to “[adapt] his arguments” to suit his needs in any given situation.[21] Some scholars have noted that Milton’s use of heroic language, demonstrated in Satan’s depiction of having a “fixt mind,” “unconquerable Will,” and “courage never to submit or yield,” contributes to the human-like complexity of his character (1.97, 106, 108). These characteristics resemble an epic hero, but his moral corruption and rebellion undermine this ideal.[21] Satan, due to his own self-deception, caused him spread that same deception to others through manipulation.[22][21] His actions influence other characters, such as the fallen angels and Adam and Eve, to be coerced into disobedience.

Such actions allude to his use of free will, which is important to his characterization. Milton portrays his rebellion against God as a deliberate choice. For Satan declares in Book 1 that “in [his] choyce,” he would rather have leadership in Hell than Heaven, emphasizing that his defying God was personal agency (261). Scholars highlight the fact that Lucifer was not created as evil, but rather, he “consciously” decided to pervert himself despite knowing the consequences out of pride.[23] He maintains autonomy throughout Paradise Lost as he is not compelled to act, but rather plans meticulously for the fall of man and carries it out of his own accord.

Satan’s psychological trajectory evolves throughout the poem as his character progresses. Early on, Milton portrays him as a figure of sublimity and a powerful personality, which captivates those who behold him.[24] He presents the qualities of a leader or a great orator. Book 4 marks a turning point in his psyche. Scholars cite Satan’s “abjection” as he internally isolates himself from his followers.[24] He laments his condition upon seeing Eden[25]:

Me miserable! which way shall I flie /

Infinite wrauth, and infinite despaire? /

Which way I flie is Hell; my self am Hell;

— John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book IV, Lines 73-75

Satan stands at the center of Paradise Lost. Milton structures much of the poem around his intentions and his actions.[18] He is not merely an “outline” or a background character, but the primary force driving the poem’s narrative.[26] Satan begins the conflict in Heaven. He orchestrates the temptation of Eve in the Garden of Eden, and his corruption of God’s creations leads to humanity being expelled from paradise. His appearances are presented in grand imagery, from his imposing stature and strength to his possession of the serpent.[26][18] He frequently shifts forms, altering his features, like in Book 3 when he becomes a cherub. Milton’s interpretation of Satan has been subject to critical debate.[18]

Opinions on the character are often sharply divided. Milton presents Satan as the origin of all evil, but some readers interpret Milton's Satan as a nuanced or sympathetic character. Romanticist critics in particular, among them William Blake, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and William Hazlitt, are known for interpreting Satan as a hero of Paradise Lost. This has led other critics, such as C. S. Lewis and Charles Williams, both of whom were devout Christians, to argue against reading Satan as a sympathetic, heroic figure.[27][28] Despite Blake thinking that Milton intended for Satan to have a heroic role in the poem, Blake himself described Satan as the "state of error," and as beyond salvation.[29]

John Carey argues that this conflict cannot be solved because the character of Satan exists in more modes and greater depth than the other characters of Paradise Lost: in this way, Milton has created an ambivalent character, and any "pro-Satan" or "anti-Satan" argument is by its nature discarding half the evidence. Satan's ambivalence, Carey says, is "a precondition of the poem's success – a major factor in the attention it has aroused".[30]

C. S. Lewis argues in his A Preface to Paradise Lost that it is important to remember what society was like when Milton wrote the poem. In particular, during that time period, there were certain "stock responses" to elements that Milton would have expected every reader to have. As examples, Lewis lists "love is sweet, death bitter, virtue lovely, and children or gardens delightful." According to Lewis, Milton would have expected readers not to view Satan as a hero at all. Lewis argues that readers far in the future romanticizing Milton's intentions is not accurate.[31]

Comparative religion scholar R. J. Zwi Werblowsky argues in his Lucifer and Prometheus that Milton's Satan is a disproportionately appealing character because of attributes he shares with the Greek Titan Prometheus. It has been called "most illuminating" for its historical and typological perspective on Milton's Satan as embodying both positive and negative values.[32] The book has also been significant in pointing out the essential ambiguity of Prometheus and his dual Christ-like/Satanic nature as developed in the Christian tradition.[33]

Adam

Adam is the first human created by God. Adam requests a companion from God:

Of fellowship I speak

Such as I seek, fit to participate

All rational delight, wherein the brute

Cannot be human consort. (8.389–392)

God approves his request then creates Eve. God appoints Adam and Eve to rule over all the creatures of the world and to reside in the Garden of Eden.

Adam is more gregarious than Eve and yearns for her company. He is completely infatuated with her. Raphael advises him to "take heed lest Passion sway / Thy Judgment" (5.635–636). But Adam's great love for Eve contributes to his disobedience to God.

Unlike the biblical Adam, before Milton's Adam leaves Paradise he is given a glimpse of the future of mankind by the Archangel Michael, which includes stories from the Old and New Testaments.

Eve

Eve is the second human created by God. God takes one of Adam's ribs and shapes it into Eve. Eve may be the more intelligent of the two. When Eve awakes after being created, she is next to a lake where she sees and admires a reflection in the water, not understanding it to be herself. A voice speaks to her and leads her to Adam, and informs the two of who each other are. When she first meets Adam, she turns away, being more interested in returning to the watery reflection, Milton's allusion to the myth of Narcissus. Recounting this to Adam she confesses that she found him less enticing than her reflection (4.477–480). Adam and Eve live in the Garden of Eden together, where they care for the garden and its creatures.

Eve delivers an autobiography in Book 4.[35]

Book four, lines 440-491 is the first instance in the poem of Eve speaking. During this speech, Eve recounts to Adam her memory of her creation. Later in book four, Milton depicts Satan whispering into Eve's ear as she sleeps, and her resulting dream reinforces her earlier admiration for her own reflection (4.800-809).

In Book 9, Milton stages a domestic debate between Adam and Eve about whether they should separate for a time to work in different parts of the Garden. The couple have always worked to this point. Eve argues that working apart will be more efficient, and ultimately, Adam agrees. Satan's temptation depends upon finding Eve alone. Having entered into the mouth of the serpent, Satan approaches Eve and begins to flatter her, alleging that her beauty makes her almost divine. When Eve asks how a snake is able to speak, Satan tells a story about how he ate the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, using the language of Renaissance love poetry. Satan explains that the fruit gave him the ability to speak and reason, and he says that Eve could use the same fruit to achieve godhead. With this story Satan overcomes Eve's obedience to God; she eats the fruit.[35] Having eaten, Eve debates with herself whether she should share with Adam. Ultimately, she goes to find Adam and convinces him to eat also.

Milton’s presentation of Eve’s character in the poem has resulted in diverging interpretations, some positive and some negative. For Angela Benninghof, “Milton employs traditional narratives, such as Genesis 1-3, The Lives of Adam and Eve, and Ovid’s Metamorphosis, and long-held misogynistic perspectives, refashioning those stories to make an argument with Eve, not for her innocence or Adam’s ultimate culpability, but rather for free will and humanity.”[36] But for Beverly McCabe, “Milton uses Eve as a catalyst to elicit weaknesses in others - namely, Adam and Satan. By juxtaposing Eve with Adam and Satan, Milton makes her a vessel through which he forewarns the reader, giving validity to the fall.”[37]

The Son of God

The Son of God is the spirit who will become incarnate as Jesus Christ, though he is never named explicitly because he has not yet entered human form. Milton believed in a subordinationist doctrine of Christology that regarded the Son as secondary to the Father and as God's "great Vice-regent" (5.609).

Milton's God in Paradise Lost refers to the Son as "My word, my wisdom, and effectual might" (3.170). The poem is not explicitly anti-trinitarian, but it is consistent with Milton's convictions. The Son is the ultimate hero of the epic and is infinitely powerful—he single-handedly defeats Satan and his followers and drives them into Hell. After their fall, the Son of God tells Adam and Eve about God's judgment. Before their fall the Father foretells their "Treason" (3.207) and that Man

with his whole posteritie must dye,

Dye hee or Justice must; unless for him

Som other able, and as willing, pay

The rigid satisfaction, death for death. (3.210–212)

The Father then asks whether there "Dwels in all Heaven charitie so deare?" (3.216) and the Son volunteers himself.

In the final book a vision of Salvation through the Son is revealed to Adam by Michael. The name Jesus of Nazareth, and the details of Jesus' story are not depicted in the poem,[38] though they are alluded to. Michael explains that "Joshua, whom the Gentiles Jesus call", prefigures the Son of God, "his name and office bearing" to "quell / The adversarie Serpent, and bring back [...] long wander[e]d man / Safe to eternal Paradise of rest".[39]

God the Father

God the Father is the creator of Heaven, Hell, the world, of everyone and everything there is, through the agency of His Son. Milton presents God as all-powerful and all-knowing, as an infinitely great being who cannot be overthrown by even the great army of angels Satan incites against him. Milton portrays God as often conversing about his plans and his motives for his actions with the Son of God. The poem shows God creating the world in the way Milton believed it was done, that is, God created Heaven, Earth, Hell, and all the creatures that inhabit these separate planes from part of Himself, not out of nothing.[40] Thus, according to Milton, the ultimate authority of God over all things that happen derives from his being the "author" of all creation. Satan tries to justify his rebellion by denying this aspect of God and claiming self-creation, but he admits to himself the truth otherwise, and that God "deserved no such return / From me, whom He created what I was".[41][42]

Raphael

Raphael is an archangel who is sent by God to Eden in order to strengthen Adam and Eve against Satan. Raphael is described as having six wings. The first pair are “regal with ornament” (5.280). The next pair are “dipped in colors of Heaven” (5.283) The third pair then “shadowed either heel with feathered mail” (5.284).

When Raphael finally reaches the bower, where Adam and Eve dwell, his conversation with Adam and Eve extends all the way from Book 5 to Book 8. In Book 5, the discussion between Adam and Raphael pertains to the nature of the angels in Heaven, including the fact that angels eat food. The archangel then describes the celebration of the angels in Heaven after the Son of God was begotten, with tables were high with heavenly food, singing and dancing. God's announcement that he has begotten a son inspires envy in Satan who decamps with his followers to the northern reaches of Heaven. In Book 6, Raphael tells a heroic tale about the War in Heaven. Ultimately, the story told by Raphael, in which Satan is portrayed as bold, manipulative, and decisive, does not prepare Adam and Eve to counter Satan's subtle temptations – and some critics argue that Raphael helped cause the Fall.[43]

In Book 7, Adam asks Raphael about the creation of the cosmos, to which Raphael “responds mild” and proceeds to tell Adam about each day of creation (7.110). In Book 8, Adam asks about the planets and the stars, wondering why the Sun, which is much larger, appears to orbit the smaller Earth. Raphael responds telling Adam that his role is not to question the secrets of the cosmos but “Rather admire” (8.75). Adam also asks Raphael if angels express their love physically. Raphael seems to blush at this statement “with a smile that glowed / Celestial rosy red” and confirms that angels have their own ways of loving and being intimate (8.618-619). Critic William Epsom notes that this “blushing” is a way that Milton humanizes the angels. [44]

Michael

Michael is an archangel who is preeminent in military prowess. He leads in battle and uses a sword which was "giv'n him temperd so, that neither keen / Nor solid might resist that edge" (6.322–323).

God sends Michael to Eden, charging him:

from the Paradise of God

Without remorse drive out the sinful Pair

From hallowd ground th' unholie, and denounce

To them and to thir Progenie from thence

Perpetual banishment. [...]

If patiently thy bidding they obey,

Dismiss them not disconsolate; reveale

To Adam what shall come in future dayes,

As I shall thee enlighten, intermix

My Cov'nant in the womans seed renewd;

So send them forth, though sorrowing, yet in peace. (11.103–117)

He is also charged with establishing a guard for Paradise.

When Adam sees him coming he describes him to Eve as

not terrible,

That I should fear, nor sociably mild,

As Raphael, that I should much confide,

But solemn and sublime, whom not to offend,

With reverence I must meet, and thou retire. (11.233–237)

Sin

Sin is the first female character presented in the epic and is introduced in Book 2. She is described to have a monstrous serpentine form such as Homer's Scylla in The Odyssey, Edmund Spenser's Error in The Faerie Queene, and the Greek myth of Lamia. She is Satan's daughter and lover, born in Heaven through parthenogenesis (2.757-760). After the angels fall from Heaven, God charges Sin with the responsibility of guarding the gates of Hell (2.850-853).

Milton’s gruesome descriptions of Sin’s serpent tail and the hellhounds she perpetually births fit within the archetype of the monstrous feminine, a term coined by Barbara Creed.[45] Sin's body is corrupted through incestuous intercourse and mutilation from the births of her children, Death and the hellhounds. This serves as an opposition to Eve's beauty and the sanctity of her sexual relationship with Adam, and the distortion of Sin's body, as well as her "lethally fertile" womb, encapsulate the abominable nature of Hell.[45][46]

Sin has been interpreted through contrasting frameworks of victimhood and seduction. Some scholars stress the significance of Sin being a victim of rape due to the nature of her intercourse with Satan and Death and the violation the hellhounds impose by repeatedly forcing themselves back into her womb.[47] Sin’s lack of bodily autonomy and the torment she suffers situate her in a position of innocence and invite compassion rather than condemnation.[47] Others claim Milton subjects Sin to horrific bodily transgressions because her overt sexuality is the reason Satan and the angels fell from Heaven.[48]

At the same time, other interpretations highlight Sin as a temptress, emphasizing the sexual connotations and symbolism embedded within her character. In “Childlessness, Monstrosity, and Redemption: Exploring Motherhood in John Milton’s Paradise Lost [49],” A. Louise Cole, explores how Sin’s role as a mother complicates her identity further, situating her within the framework of both postlapsarian and prelapsarian sin. Cole examines Sin as the first mother in Paradise Lost saying, “Milton’s decision to make Sin female and a mother also allows us to read her character as the embodiment of the Son’s curse upon Eve and her descendants.” The sexual implications and actions of Sin set a complex analysis according to Cole she is both the object of sexual desire but has no agency of her own.

John S.P. Tatlock attributes James 1:15 as the foundation for Milton’s allegory of Sin and her son Death: “Then when lust hath conceived, it bringeth forth sin: and sin, when it is finished, bringeth forth death."[50] Robert B. White asserts that the foundation is the Holy Trinity, which Milton perverts to frame Sin as a hellish version of the Son.[51]

Critics offer mixed opinions on the effectiveness of Milton's allegorical framework. Joseph Addison published his critiques in his magazine The Spectator in the early 18th century. Addison admired the captivating and vivid quality of Milton’s descriptions, but believed Sin and Death’s fantastical qualities undermined the serious tone and realism of stories in the epic genre.[52] Samuel Johnson similarly argued that Milton’s allegorical argument is weakened by the tangible impacts and interactions Sin and Death have despite representing abstract concepts.[53]

Other academics contend that the allegory provides a compelling contrast to the excellence of God and His creations. Professor James S. Baumlin argues that Milton’s allegory extends to Hell’s other inhabitants and likens each of them to one of the Seven Deadly Sins.[24] Sin exhibits a dual allegory as she symbolizes both the concept of sin and the vice of Lust.[24] Akin to White, Joseph H. Summers views Sin as an absurd imitation of the Son because her theatrical proclamations mock the Son’s humility and sacrifice.[54]

Death

Death in Paradise Lost is represented as an undefined shadowy figure. Readers are first introduced to Death in Book 2 when Satan encounters Death at the gates of Hell. Milton gives no clear description as to what Death looks like other than that it is a shapeless black shadow. Milton presents Death as the incestuous offspring of Sin, who herself is born from Satan, making Death the direct result of Satan’s earlier rebellion. According to A Milton Encyclopedia, Death’s undefined and shifting form reflects his status as an allegorical being whose identity is rooted in disorder rather than stable creation.[55] His birth situates him as both a consequence of Satan’s actions and an extension of the chaos that rebellion produces.

In Book 10, Satan returns towards of Hell and encounters Sin and Death who are going down to earth, which Satan has effectively conquered by successfully tempting Adam and Eve. They will infect and destroy all living things. In Book 10, Death again is described as merely a “shadow" (10.264). The interaction of Sin and Death shows them working together to continue the disorder that began with Satan’s rebellion. As Stephen Fallon explains in “Milton’s Sin and Death: The Ontology of Allegory in Paradise Lost,” Milton uses Sin and Death to show how allegorical beings can both embody and perpetuate the consequences of rebellion.[56] In this scene, Death’s presence illuminates the ongoing spread of that chaos as he and Sin move into the world beyond Hell.

Beelzebub

Beelzebub, in Paradise Lost, is Satan's second-in-command and the fallen angel who plays a central role in organizing the demons after their expulsion from Heaven (1.79). He is depicted as cunning, persuasive, and politically strategic, often acting as the voice that articulates Satan's broader plans to the infernal council (2.378-380). Throughout the epic, Beelzebub's speeches help shape the demons' course of action, positioning him as one of Hell's leaders (2.299-301).

Remove ads

Locations

Hell

Paradise Lost by John Milton takes place in many different settings, the first of which is Hell. In Book 1, Hell is described as a "dismal situation waste and wild / A dungeon horrible" with flames that shed not light but rather "darkness visible." Milton alludes to the inscription above the entrance to Dante's Inferno when he calls Hell a place "where peace / And rest can never dwell, hope never comes / That comes to all but torture without end" (1.59-67).

Pandemonium is a city erected in Hell under the leadership of Mammon, one of Satan's followers, whom Milton calls "the least erected spirit that fell from Heav'n (1.679). The fallen angels dig up metal and "ribs of gold" (1.690) and use a smelting technique to grow a grand palace up out of the ground in a parody of organic creation. C.S. Lewis in A Preface to Paradise Lost writes that Mammon "believes that Hell can be made into a substitute for Heaven" and that Mammon's tragedy is that he "never understood the difference between Hell and Heaven at all. The tragedy has been no tragedy for him: he can do very well without Heaven."[57]

Remove ads

Themes

Summarize

Perspective

Marriage

Milton held many opinions on what the ideal marriage was supposed to be. A year after Mary Powell left him weeks after their marriage in 1642, Milton published The Divorce Tracts, detailing his opinions on marriage and divorce. In the book Tetrachordon, Milton defines marriage as "a love fitly dispos'd to mutual help and comfort of life; this is that happy Form of marriage naturally arising from the very heart of divine institution in the Text".[58] John Halkett states that, to Adam, Eve represents a more complex space in his heart as she helps satisfy the emotional needs[59] he expressed to God[60], bringing him true harmony as his desire. Hermine Van Nuis clarifies, that although there was stringency specified for the roles of male and female, Adam and Eve unreservedly accept their designated roles.[61] Rather than viewing these roles as forced upon them, each uses their assignment as an asset in their relationship with each other. These distinctions can be interpreted as Milton's view on the importance of mutuality between husband and wife.

When examining the relationship between Adam and Eve, some critics apply either an Adam-centered or Eve-centered view of hierarchy and importance to God. David Mikics argues, by contrast, these positions "overstate the independence of the characters' stances, and therefore miss the way in which Adam and Eve are entwined with each other".[62]Others like Halkett argue that these very differences help set up the inherent hierarchy between husband and wife. He states that "Milton argues the inequality of the sexes from the differences in their appearance: their hair, forehead, and eyes give evidence of different intellectual and moral powers,"[63] which the Son reminds Adam when he confronts the pair after the fall, as Eve was to "attract thy love, not thy subjection."[64] However, Kristin Pruitt argues that both reciprocity and hierarchy are at equal play in the relationship[65]. Eve sees Adam as her faithful guide, and Adam sees her as a priceless companion, and through this they develop each other's gifts[65]. Pruitt states that "the ideal human marriage....is not masculinist or feminist but essentially...humanist."[65] Milton's narrative depicts a relationship where the husband and wife (here, Adam and Eve) depend on each other and, through each other's differences, thrive.[62] Even though there are several instances where Adam communicates directly with God while Eve must go through Adam to God[66], Pruitt suggests that through her relationship with Adam, she has gained "God in her" and Adam must honor that.[65]

Although Milton does not directly mention divorce, critics posit theories on Milton's view of divorce based upon their inferences from the poem and from his tracts on divorce written earlier in his life. Other works by Milton suggest he viewed marriage as an entity separate from the church. Discussing Paradise Lost, Biberman entertains the idea that "marriage is a contract made by both the man and the woman".[67] These ideas imply Milton may have thought that both man and woman should have equal access to marriage and to divorce.

Idolatry

Milton's 17th-century contemporaries by and large criticised his ideas and considered him a radical, mostly because of his republican political views and heterodox theological opinions. One of Milton's most controversial arguments centred on his concept of what is idolatrous, a subject which is deeply embedded in Paradise Lost.

Milton's first criticism of idolatry focused on the constructing of temples and other buildings to serve as places of worship. In Book XI of Paradise Lost, Adam tries to atone for his sins by offering to build altars to worship God. In response, the angel Michael explains that Adam does not need to build physical objects to experience the presence of God.[68] Joseph Lyle points to this example, explaining: "When Milton objects to architecture, it is not a quality inherent in buildings themselves he finds offensive, but rather their tendency to act as convenient loci to which idolatry, over time, will inevitably adhere."[69] Even if the idea is pure in nature, Milton thought it would unavoidably lead to idolatry simply because of the nature of humans. That is, instead of directing their thoughts towards God, humans will turn to erected objects and falsely invest their faith there. While Adam attempts to build an altar to God, critics note Eve is similarly guilty of idolatry, but in a different manner. Harding believes Eve's narcissism and obsession with herself constitutes idolatry.[70] Specifically, Harding claims that "under the serpent's influence, Eve's idolatry and self-deification foreshadow the errors into which her 'Sons' will stray".[70] Much like Adam, Eve falsely places her faith in herself, the Tree of Knowledge, and to some extent the Serpent, all of which do not compare to the ideal nature of God.

Milton made his views on idolatry more explicit with the creation of Pandæmonium and his allusion to Solomon's temple. In the beginning of Paradise Lost and throughout the poem, there are several references to the rise and eventual fall of Solomon's temple. Critics elucidate that "Solomon's temple provides an explicit demonstration of how an artefact moves from its genesis in devotional practice to an idolatrous end."[71] This example, out of the many presented, distinctly conveys Milton's views on the dangers of idolatry. Even if one builds a structure in the name of God, the best of intentions can become immoral in idolatry. The majority of these similarities revolve around a structural likeness, but as Lyle explains, they play a greater role. By linking Saint Peter's Basilica and the Pantheon to Pandemonium—an ideally false structure—the two famous buildings take on a false meaning.[72] This comparison best represents Milton's Protestant views, as it rejects both the purely Catholic perspective and the Pagan perspective.

In addition to rejecting Catholicism, Milton revolted against the idea of a monarch ruling by divine right. He saw the practice as idolatrous. Barbara Lewalski concludes that the theme of idolatry in Paradise Lost "is an exaggerated version of the idolatry Milton had long associated with the Stuart ideology of divine kingship".[73] In the opinion of Milton, any object, human or non-human, that receives special attention befitting of God, is considered idolatrous.

Criticism of monarchy

Although Satan's army inevitably loses the war against God, Satan achieves a position of power and begins his reign in Hell with his band of loyal followers, composed of fallen angels, which is described to be a "third of heaven". Similar to Milton's republican sentiments of overthrowing the King of England for both better representation and parliamentary power, Satan argues that his shared rebellion with the fallen angels is an effort to "explain the hypocrisy of God",[citation needed] and in doing so, they will be treated with the respect and acknowledgement that they deserve. As Wayne Rebhorn argues, "Satan insists that he and his fellow revolutionaries held their places by right and even leading him to claim that they were self-created and self-sustained" and thus Satan's position in the rebellion is much like that of his own real-world creator.[74]

Milton scholar John Leonard interpreted the "impious war" between Heaven and Hell as civil war:[75][page needed]

Paradise Lost is, among other things, a poem about civil war. Satan raises "impious war in Heav'n" (i 43) by leading a third of the angels in revolt against God. The term "impious war" implies that civil war is impious. But Milton applauded the English people for having the courage to depose and execute King Charles I. In his poem, however, he takes the side of "Heav'n's awful Monarch" (iv 960). Critics have long wrestled with the question of why an antimonarchist and defender of regicide should have chosen a subject that obliged him to defend monarchical authority.

The editors at the Poetry Foundation argue that Milton's criticism of the English monarchy was being directed specifically at the Stuart monarchy and not at the monarchical system of government in general.[3]

In a similar vein, C. S. Lewis argued that there was no contradiction in Milton's position in the poem since "Milton believed that God was his 'natural superior' and that Charles Stuart was not."[75][page needed]

Moral ambiguity

The critic William Empson claimed the poem was morally ambiguous, with Milton's complex characterization of Satan playing a large part in Empson's claim of moral ambiguity.[75][page needed] For context, the second volume of Empson's authorized biography was titled: William Empson: Against the Christians. In it his authorized biographer describes "Empson's visceral loathing of Christianity."[76] He spent a large amount of his career attacking Christianity, demonizing it as "wickedness" and claiming that Milton's God was "sickeningly bad."[77] For example, Empson portrays Milton's God as akin to a "Stalinist" tyrant "who enslaves His human creations to serve His own narcissism."

From there, Empson gives fake praise that is really an attack, saying that "Milton deserves credit for making God wicked, since the God of Christianity is 'a wicked God'." John Leonard states that "Empson never denies that Satan's plan is wicked. What he does deny is that God is innocent of its wickedness: 'Milton steadily drives home that the inmost counsel of God was the Fortunate Fall of man; however wicked Satan's plan may be, it is God's plan too [since God in Paradise Lost is depicted as being both omniscient and omnipotent].'"[75][page needed] Leonard notes that this interpretation was challenged by Dennis Danielson in his book Milton's Good God (1982).[75][page needed]

Alexandra Kapelos-Peters explains that: "as Danielson logically asserts, foreknowledge is not commensurate with culpability. Although God knew that Adam and Eve would eat the forbidden fruit of knowledge, He neither commanded them to do so, nor influenced their decision." Moreover, God gives humans free will to choose to do good or evil, while a tyrant would do the very opposite and deny free will by controlling his subjects' actions like a puppet-master. She says Danielson and Milton "demonstrate one crucial point: the presence of sin in the world is attributable to human agency and free will. Danielson argues that free will is crucial, because without it humanity would have only been serving necessity, and not participating in a free love act with the divine."[78] She notes that in Paradise Lost, God says: "They trespass, Authors to themselves in all, Both what they judge and what they choose; for so I formd them free, and free they must remain."

Kapelos-Peters adds: "Milton demonstrates that far from being a tyrannical lord, God and the Son function as a collaborative team that desire nothing but the return of man to his pre-fallen state. Furthermore, God is not even able to dominate in this aspect because human agency and free-will are not abandoned. Not only will the Son sacrifice himself pre-emptively in Book 3 for the not-yet-occurred Fall of Man, but Man himself will have a role in his own salvation. To successfully navigate atonement, humanity will have to admit and repent of their former disobedience."

C. S. Lewis also rebutted the approach of people like Empson. Lewis wrote: "The first qualification for judging any piece of workmanship from a corkscrew to a cathedral is to know what it is – what it was intended to do and how it is meant to be used."[79] Lewis said the poem was a genuine Christian morality tale.[75][page needed] In Lewis's book A Preface to Paradise Lost, he discusses the theological similarities between Paradise Lost and St. Augustine, and says that "The Fall is simply and solely Disobedience – doing what you have been told not to do: and it results from Pride – from being too big for your boots, forgetting your place, thinking that you are God."[28]

Free Will

One of the major themes seen throughout Milton’s Paradise Lost is free will, used as a way to “justify the ways of God to men” (PL 1. 26)[80] . Scholar Barry Edward Gross suggests that Milton uses characters like Adam and Eve to illustrate a choice to remain obedient to God; however, it is Eve’s love for her own image and Adam’s fascination with Eve that foil their decision-making.[81] Additionally, writer William Walker argues that faith in God does not control the freedom of men.[82]

Remove ads

Cosmology

Summarize

Perspective

Cosmology - as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary - is "The science or theory of the universe as an ordered whole, and of the general laws which govern it."[83] In Paradise Lost, John Milton describes the structure of the universe in a way that does not explicitly support the heliocentric or geocentric models of the solar system, but rather a structure that Milton himself designed in the process of writing the poem.[84] At the time of Paradise Lost's publication, the geocentric model of the solar system still had widespread credence, though there was a growing opposition towards the model from those who believed the solar system to be heliocentric. Milton himself did not strictly align himself with one theory or the other[85], the impact of which is apparent in his structuring of the universe in Paradise Lost.

According to Milton, the universe of Paradise Lost is made of three primary layers: Heaven, Chaos, and Hell. Though Milton himself never created a map detailing the exact structure of the universe in the poem, many Paradise Lost historians have established that it is structured along the lines of the vast expanse of Heaven being above the vast expanse of Chaos, where is Earth hanging from a golden chain that descends from Heaven.[86] Below Chaos and Earth, there is the entity of Hell.[87]

The structure of the universe in Paradise Lost has been widely discussed in light of Milton's theological views. In some ways, Milton's poem makes room for emerging new models of the cosmos. But some scholars say that Milton resists the seventeenth-century scientific consensus in the name of being true to the Bible, and he is skeptical in the poem about those who would try to understand the secrets of the universe.[85] Jacob Taylor says that "although Milton writes with three astronomies, the Copernican, Epicurean, and Ptolemaic, he emphasizes that the faith is a far surpassing beginning than any astronomical remodeling." [88]

Remove ads

Interpretation and critique

Summarize

Perspective

Eighteenth-century critics

The writer and critic Samuel Johnson wrote that Paradise Lost shows off Milton's "peculiar power to astonish" and that Milton "seems to have been well acquainted with his own genius, and to know what it was that Nature had bestowed upon him more bountifully than upon others: the power of displaying the vast, illuminating the splendid, enforcing the awful, darkening the gloomy, and aggravating the dreadful".[89]

William Blake famously wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: "The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it."[90] This quotation succinctly represents the way in which some 18th- and 19th-century English Romantic poets viewed Milton.

Christian epic

Tobias Gregory wrote that Milton was "the most theologically learned among early modern epic poets. He was, moreover, a theologian of great independence of mind, and one who developed his talents within a society where the problem of divine justice was debated with particular intensity."[91] Gregory says that Milton is able to establish divine action and his divine characters in a superior way to other Renaissance epic poets, including Ludovico Ariosto or Torquato Tasso.[92]

In Paradise Lost Milton also ignores the traditional epic format of a plot based on a mortal conflict between opposing armies with deities watching over and occasionally interfering with the action. Instead, both divinity and humanity are involved in a conflict that, while momentarily ending in tragedy, offers a future salvation.[92] In both Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, Milton incorporates aspects of Lucan's epic model, the epic from the view of the defeated. Although he does not accept the model completely within Paradise Regained, he incorporates the "anti-Virgilian, anti-imperial epic tradition of Lucan".[93] Milton goes further than Lucan in this belief and "Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained carry further, too, the movement toward and valorization of romance that Lucan's tradition had begun, to the point where Milton's poems effectively create their own new genre".[94] The Catholic Church reacted by banning the poem and placing it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[a]

Remove ads

Iconography

Summarize

Perspective

The first illustrations to accompany the text of Paradise Lost were added to the fourth edition of 1688, with one engraving prefacing each book, of which up to eight of the twelve were by Sir John Baptist Medina, one by Bernard Lens II, and perhaps up to four (including Books I and XII, perhaps the most memorable) by another hand.[95] The engraver was Michael Burghers (given as 'Burgesse' in some sources[96]). By 1730, the same images had been re-engraved on a smaller scale by Paul Fourdrinier.

Some of the most notable illustrators of Paradise Lost included William Blake, Gustave Doré, and Henry Fuseli. However, the epic's illustrators also include John Martin, Edward Francis Burney, Richard Westall, Francis Hayman, and many others.

Outside of book illustrations, the epic has also inspired other visual works by well-known painters like Salvador Dalí who executed a set of ten colour engravings in 1974.[97] Milton's achievement in writing Paradise Lost while blind (he dictated to helpers) inspired loosely biographical paintings by both Fuseli[98] and Eugène Delacroix.[99]

- In Sin, Death and the Devil (1792), James Gillray caricatured the political battle between Pitt and Thurlow as a scene from Paradise Lost. Pitt is Death and Thurlow Satan, with Queen Charlotte as Sin in the middle.

- The Shepherd's Dream, from "Paradise Lost", Henry Fuseli (1793)

- John Martin, Eve's Dream, Satan Aroused, from Paradise Lost (1824–1827). Mezzotint, plate, 14 × 20.2 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Translations

Tamil

Book 1 of Paradise Lost was translated into Tamil under the title Swarga Neekam MutharKandam (1895) by V. P. Subramania Mudaliar (1857-1946). The translator included annotations and a biography of Milton in the translation.[100][101]

Another translation titled Iḻanta corkkam: Kāviyam was published on 2020 by H. Mujeeb Rahman as an Amazon Kindle edition.[citation needed]

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads