Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Pax Americana

Historical concept From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Pax Americana[1][2][3] (Latin for 'American Peace', modeled after Pax Romana and Pax Britannica), often identified with the "Long Peace", is a term applied to the concept of relative peace in the Western Hemisphere and later in the world after the end of World War II in 1945, when the United States of America[4] became the world's foremost economic, cultural, and military power exercising primary responsibilities for world order. Though in large measure based on consent and cooperation, the defining feature of the Pax Americana is unipolarity, world organization around a single center of power.[5]

In this sense, Pax Americana has come to describe the military and economic position of the United States relative to other nations. In the aftermath of World War II the American federal government enacted the Marshall Plan, the transferring of US$13.3 billion (the equivalent of $173 billion in 2023) in economic recovery programs to Western European countries; the Marshall Plan has been described as "the launching of the Pax Americana".[6]

Remove ads

Early period

Summarize

Perspective

The first articulation of a Pax Americana occurred after the end of the American Civil War (in which the United States both quashed its greatest disunity and demonstrated the ability to field millions of well-equipped soldiers utilizing modern tactics) with reference to the peaceful nature of the North American geographical region, and was abeyant at the commencement of the First World War. Its emergence was concurrent with the development of the idea of American exceptionalism. This view holds that the U.S. occupies a special niche among developed nations[7] in terms of its national credo, historical evolution, political and religious institutions, and unique origins. The concept originates from Alexis de Tocqueville,[8] who asserted that the then-50-year-old United States held a special place among nations because it was a country of immigrants and the first modern democracy. From the establishment of the United States after the American Revolution until the Spanish–American War, the foreign policy of the United States had a regional, instead of global, focus. The Pax Americana, which the Union enforced upon the states of central North America, was a factor in the United States' national prosperity. The larger states were surrounded by smaller states, but these had no anxieties: no standing armies to require taxes and hinder labor; no wars or rumors of wars that would interrupt trade; there is not only peace, but security, for the Pax Americana of the Union covered all the states within the federal constitutional republic.[9] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first time the phrase appeared in print was in the August 1894 issue of Forum: "The true cause for exultation is the universal outburst of patriotism in support of the prompt and courageous action of President Cleveland in maintaining the supremacy of law throughout the length and breadth of the land, in establishing the pax Americana."[10]

With the rise of the New Imperialism in the Western hemisphere at the end of the 19th century, debates arose between imperialist and isolationist factions in the U.S. Here, Pax Americana was used to connote the peace across the United States and, more widely, as a Pan-American peace under the aegis of the Monroe Doctrine. Those who favored traditional policies of avoiding foreign entanglements included labor leader Samuel Gompers and steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie. American politicians such as Henry Cabot Lodge, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt advocated an aggressive foreign policy, but the administration of President Grover Cleveland was unwilling to pursue such actions. On January 16, 1893, U.S. diplomatic and military personnel conspired with a small group of individuals to overthrow the constitutional government of the Kingdom of Hawaii and establish a Provisional Government and then a republic. On February 15, they presented a treaty for annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the U.S. Senate, but opposition to annexation stalled its passage. The United States finally opted to annex Hawaii by way of the Newlands Resolution in July 1898.

After its victory in the Spanish–American War of 1898 and the subsequent acquisition of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam, the United States had gained a colonial empire. By ejecting Spain from the Americas, the United States shifted its position to an uncontested regional power, and extended its influence into Southeast Asia and Oceania. Although U.S. capital investments within the Philippines and Puerto Rico were relatively small, these colonies were strategic outposts for expanding trade with Latin America and Asia, particularly China. In the Caribbean area, the United States established a sphere of influence in line with the Monroe Doctrine, not explicitly defined as such, but recognized in effect by other governments and accepted by at least some of the republics in that area.[11] The events around the start of the 20th century demonstrated that the United States undertook an obligation, usual in such cases, of imposing a "Pax Americana".[11] As in similar instances elsewhere, this Pax Americana was not quite clearly marked in its geographical limit, nor was it guided by any theoretical consistency, but rather by the merits of the case and the test of immediate expediency in each instance.[11] Thus, whereas the United States enforced a peace in much of the lands southward from the Nation and undertook measures to maintain internal tranquility in such areas, the United States on the other hand withdrew from interposition in Mexico.[11]

European powers largely regarded these matters as the concern of the United States. Indeed, the nascent Pax Americana was, in essence, abetted by the policy of the United Kingdom, and the preponderance of global sea power which the British Empire enjoyed by virtue of the strength of the Royal Navy.[12] Preserving the freedom of the seas and ensuring naval dominance had been the policy of the British since victory in the Napoleonic Wars. As it was not in the interests of the United Kingdom to permit any European power to interfere in Americas, the Monroe Doctrine was indirectly aided by the Royal Navy. British commercial interests in South America, which comprised a valuable component of the informal empire that accompanied Britain's overseas possessions, and the economic importance of the United States as a trading partner, ensured that intervention by Britain's rival European powers could not engage with the Americas.

The United States lost its Pacific and regionally bounded nature towards the end of the 19th century. The government adopted protectionism after the Spanish–American War and built up the navy, the "Great White Fleet", to expand the reach of U.S. power. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, he accelerated a foreign policy shift away from isolationism towards foreign intervention which had begun under his predecessor, William McKinley. The Philippine–American War (1899–1913) arose from the ongoing Philippine Revolution against imperialism.[13] Interventionism found its formal articulation in the 1904 Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, proclaiming the right of the United States to intervene in the affairs of weak states in the Americas in order to stabilize them, a moment that underlined the emergent U.S. regional hegemony. By 1900, the United States possessed the world's largest industrial capacity and national income, having surpassed both the United Kingdom and Germany.[14]

Remove ads

Interwar period

Summarize

Perspective

The United States had been criticized for not taking up the hegemonic mantle following the disintegration of Pax Britannica before the First World War and during the interwar period due to the absence of established political structures, such as the World Bank or United Nations which would be created after World War II, and various internal policies, such as protectionism.[2][15][16][17] Though, the United States participated in the Great War, according to Woodrow Wilson:

[...] to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power and to set up amongst the really free and self-governed peoples of the world such a concert of purpose and of action as will henceforth insure the observance of those principles.

[...] for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own government, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.[2]

The United States' entry into the Great War marked the abandonment of the traditional American policy of isolation and independence of world politics. Not at the close of the Civil War, not as the result of the Spanish War, but in the Interwar period did the United States become a part of the international system.[2] With this global reorganization from the Great War, there were those in the American populace that advocated an activist role in international politics and international affairs by the United States.[2] Activities that were initiated did not fall into political-military traps and, instead, focused on economic-ideological approaches that would increase the American Empire and general worldwide stability.[18] Following the prior path, a precursor to the United Nations and a league to enforce peace, the League of Nations, was proposed by Woodrow Wilson.[2] This was rejected by the American Government in favor of more economic-ideological approaches and the United States did not join the League. Additionally, there were even proposals of extending the Monroe Doctrine to Great Britain put forth to prevent a second conflagration on the European theater.[19] Ultimately, the United States' proposals and actions did not stop the factors of European nationalism spawned by the previous war, the repercussions of Germany's defeat, and the failures of the Treaty of Versailles from plunging the globe into a Second World War.[20]

Between World War I and World War II, America also sought to continue to preserve Pax America as a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.[19] Some sought the peaceful and orderly evolution of existing conditions in the western hemisphere and nothing by immediate changes.[19] Before 1917, the position of the United States government and the feelings of the nation in respect to the "Great War" initially had properly been one of neutrality.[19] Its interests remained untouched, and nothing occurred of a nature to affect those interests.[19]

Pax Americana was not just an idea reserved for the United States Government. Business leaders from across the major corporations in the US all sought to steer America into a time of Pax Americana. For them by creating better trading conditions through peace and stability, they could expand their own businesses and maintain US superiority in the global stage.[21] As the United State Government had close ties to the largest businesses in America, it was easier for these businesses to sway political acts in their favour. These businesses also helped create the conditions for Pax Americana using foreign investments, loans and trade to secure influence without military commitment.[21]

The average American's sympathies, on the other hand, if the feelings of the vast majority of the nation had been correctly interpreted, was with the Allied (Entente) Powers.[19] The population of the United States was revolted at the ruthlessness of the Prussian doctrine of war, and German designs to shift the burden of aggression encountered skeptical derision.[19] The American populace saw themselves safeguarding liberal peace in the Western World. To this end, the American writer Roland Hugins stated that the United States is the only strong nation that has not entered on a career of imperial conquest and does not aspire to be the Romans of tomorrow or the "masters of the world." There is in America little of militarism, the Americans are not enamored of glamour or glory. Their desire to be left alone to work out their own destiny has been manifest from the birth of the republic.[22][2]

It was observed during this time that the initial defeat of Germany opened a moral recasting of the world.[19] The battles between Germans and Allies were seen as far less battles between different nations than they represent the contrast between Liberalism and reaction, between the aspirations of democracy and the Wilhelminism gospel of iron.[19][23]

According to Swen Holdar, the founder of geopolitics Rudolf Kjellen (1864–1922) predicted the era of US global supremacy using the term Pax Americana shortly after World War I.[24] Writing in 1945, Ludwig Dehio remembered that the Germans used the term Pax Anglosaxonica in a sense of Pax Americana since 1918:

Now [1918] the [American colonial] cutting had grown into a tree that bade fair to overshadow the globe with its foliage. Amazed and shaken, we Germans began to discuss the possibility of a Pax Anglosaxonica as a world-wide counterpart to the Pax Romana. Suddenly the tendency toward global unification towered up, ready to gather the separate national states of Europe together under one banner and blanket in a larger cohesion ...[25]

Remove ads

Postwar period

Summarize

Perspective

The modern Pax Americana era is cited by supporters and critics of U.S. foreign policy since the beginning of World War II. In 1941, before the entrance of the United States into the War, US Ambassador to Canada, James H. R. Cromwell, published a book, titled Pax Americana.[26] As the title implies, the book envisages the postwar world order with the interventionist US policy. Another wartime book confirms that the postwar era "might well be known as Pax Americana." Both the world and the United States need American peace and the United States must insist upon it and accept nothing less.[27] Explicit criticisms of the idea of Pax Americana appear in the United States synchronously.[28]

From 1945 to 1991, Pax Americana was a partial international order, as it applied only to the Western world, being preferable for some authors to speak about a Pax Americana et Sovietica.[29] Many commentators and critics focus on American policies from 1992 to the present, and as such, it carries different connotations depending on the context. For example, it appears three times in the 90-page document, Rebuilding America's Defenses,[30] by the Project for the New American Century, but is also used by critics to characterize American dominance and hyperpower status as imperialist in function and basis. From about the mid-1940s until 1991, U.S. foreign policy was dominated by the Cold War, and characterized by its significant international military presence and greater diplomatic involvement. Seeking an alternative to the isolationist policies pursued after World War I, the United States defined a new policy called containment to oppose the spread of Soviet communism.

The modern Pax Americana may be seen as similar to the period of peace in Rome, Pax Romana. In both situations, the period of peace was 'relative peace'. During both Pax Romana and Pax Americana wars continued to occur, but it was still a prosperous time for both Western and Roman civilizations. It is important to note that during these periods, and most other times of relative tranquility, the peace that is referred to does not mean complete peace. Rather, it simply means the civilization prospered in their military, agriculture, trade, and manufacturing.

Pax Britannica heritage

From the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 until the First World War in 1914, the United Kingdom played the role of offshore-balancer in Europe, where the balance of power was the main aim. It was also in this time that the British Empire became the largest empire of all time. The global superiority of British military and commerce was guaranteed by dominance of a Europe lacking in strong nation-states, and the presence of the Royal Navy on all of the world's oceans and seas. In 1905, the Royal Navy was superior to any two navies combined in the world. It provided services such as suppression of piracy and slavery.

In this era of peace, though, there were several wars between the major powers: the Crimean War, the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Prussian War, the Franco-Prussian War, and the Russo-Japanese War, as well as numerous other wars. William Wohlforth has argued that this period of tranquility, sometimes termed La Belle Époque, was actually a series of hegemonic states imposing a peaceful order. In Wohlforth's view, Pax Britannica transitioned to Pax Russica and then to Pax Germanica, before ultimately, between 1853 and 1871, ceasing to be a Pax of any kind.[31]

During the Pax Britannica, America developed close ties with Britain, evolving into what has become known as a "special relationship" between the two. The many commonalities shared with the two nations (such as language and history) drew them together as allies. Under the managed transition of the British Empire to the Commonwealth of Nations, members of the British government, such as Harold Macmillan, liked to think of Britain's relationship with America as similar to that of a progenitor Greece to America's Rome.[32] Throughout the years, both have been active in North American, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries.

In 1942, Advisory Committee on Postwar Foreign Policy envisaged that the United States may have to supplant the British Empire. Therefore, the United States "must cultivate a mental view toward world settlement after this war which will enable us to impose our own terms, amounting perhaps to a Pax Americana".[33] The transition from the British Empire to the Pax Americana is commonly dated to 1947 when the British rule ended in India, Pakistan, Palestine and the eastern Mediterranean, and the Truman Doctrine announced.[34]

Late 20th century

After the Second World War, no armed conflict emerged among major Western nations themselves, and no nuclear weapons were used in open conflict. The United Nations was also soon developed after World War II to help keep peaceful relations between nations and establishing the veto power for the permanent members of the UN Security Council, which included the United States.

In the second half of the 20th century, the USSR and US superpowers were engaged in the Cold War, which can be seen as a struggle between hegemonies for global dominance. After 1945, the United States enjoyed an advantageous position with respect to the rest of the industrialized world. In the Post–World War II economic expansion, the US was responsible for half of global industrial output, held 80 percent of the world's gold reserves, and was the world's sole nuclear power. The catastrophic destruction of life, infrastructure, and capital during the Second World War had exhausted the imperialism of the Old World, victor and vanquished alike. The largest economy in the world at the time, the United States recognized that it had come out of the war with its domestic infrastructure virtually unscathed and its military forces at unprecedented strength. Military officials recognized the fact that Pax Americana had been reliant on the effective United States air power, just as the instrument of Pax Britannica a century earlier was its sea power.[35] In addition, a unipolar moment was seen to have occurred following the collapse of the Soviet Union.[36]

The term Pax Americana was explicitly used by John F. Kennedy in the 1960s, who advocated against the idea, arguing that the Soviet bloc was composed of human beings with the same individual goals as Americans and that such a peace based on "American weapons of war" was undesirable:

I have, therefore, chosen this time and place to discuss a topic on which ignorance too often abounds and the truth too rarely perceived. And that is the most important topic on earth: peace. What kind of peace do I mean and what kind of a peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, and the kind that enables men and nations to grow, and to hope, and build a better life for their children – not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women, not merely peace in our time but peace in all time.[37]

No other US Presidents claimed Pax Americana. As Kennedy, Richard Nixon and George Bush the senior referred to Pax Americana but exclusively to deny its existence in fact and intent. For this reason, the concept was called "undiplomatic".[38]

Beginning around the Vietnam War, the 'Pax Americana' term had started to be used by the critics of American Imperialism. Here in the late 20th-century conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States, the charge of Neocolonialism was often aimed at Western involvement in the affairs of the Third World and other developing nations.[39][40][41][42][43] NATO became regarded as a symbol of Pax Americana in West Europe:

The visible political symbol of the Pax Americana was NATO itself ... The Supreme Allied Commander, always an American, was an appropriate title for the American proconsul whose reputation and influence outweighed those of European premiers, presidents, and chancellors.[44]

In one of the first criticisms of "Pax Americana" in 1943 Nathaniel Peffer wrote:

It is neither feasible nor desirable ... Pax Americana can be established and maintained only by force, only by means of a new, gigantic imperialism operating with the instrumentalities of militarism and the other concomitants of imperialism ... The way to dominion is through empire and the price of dominion is empire, and empire generates its own opposition.[45]

He did not know if it would happen: "It is conceivable that ... America might drift into empire, imperceptibly, stage by stage, in a kind of power-politics gravitation." He also noted that America was heading precisely in that direction: "That there are certain stirrings in this direction is apparent, though how deep they go is unclear."[45]

The depth soon became clarified. Two later critics of Pax Americana, Michio Kaku and David Axelrod, interpreted the outcome of Pax Americana: "Gunboat diplomacy would be replaced by Atomic diplomacy. Pax Britannica would give way to Pax Americana." After the war, with the German and British militaries in tatters, only one force stood on the way to Pax Americana: the Soviet Army.[46] Four years after this criticism was written, the Red Army withdrew, paving the way for the unipolar moment. Joshua Muravchik commemorated the event by titling his 1991 article, "At Last, Pax Americana". He detailed:

Last but not least, the Gulf War marks the dawning of the Pax Americana. True, that term was used immediately after World War II. But it was a misnomer then because the Soviet empire – a real competitor with American power – was born at the same moment. The result was not a "pax" of any kind, but a cold war and a bipolar world ... During the past two years, however, Soviet power has imploded and a bipolar world has become unipolar.[47]

The following year, in 1992, a US strategic draft for the post-Cold War period was leaked to the press. The person responsible for the confusion, former Assistant Secretary of State, Paul Wolfowitz, confessed seven years later: "In 1992 a draft memo prepared by my office at the Pentagon ... leaked to the press and sparked a major controversy." The draft's strategy aimed "to prevent any hostile power from dominating" a Eurasian region "whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power". He added: "Senator Joseph Biden ridiculed the proposed strategy as 'literally a Pax Americana ... It won't work ...' Just seven years later, many of these same critics seem quite comfortable with the idea of a Pax Americana."[48] The post-Cold War period, concluded William Wohlforth, much less ambiguously deserves to be called Pax Americana. "Calling the current period the true Pax Americana may offend some, but it reflects reality".[31]

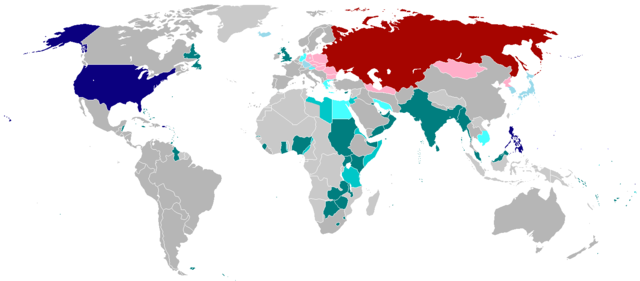

Contemporary power

Since 1991,[49] the Pax Americana was based on the military preponderance beyond challenge by any combination of rival powers and projection of power throughout the world's commons – neutral sea, air and space. This projection is coordinated by the Unified Command Plan which divides the world on regional branches controlled by a single command. The "right to command," translated into Latin, gives imperium, "commands" (plural) imperia.[50] The US Combatant Commanders have often been associated with the Roman proconsuls[51][52][53][54] and a complete book was devoted to the comparison.[55]

Integrated with it are global network of military alliances (the Rio Pact, NATO, ANZUS and bilateral alliances with Japan and several other states) coordinated by Washington in a hub-and-spokes system and worldwide network of several hundreds of military bases and installations. Neither the Rio Treaty, nor NATO, for Robert J. Art, "was a regional collective security organization; rather both were regional imperia run and operated by the United States".[56] Former Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski drew an expressive summary of the military foundation of Pax Americana shortly after the unipolar moment:

In contrast [to the earlier empires], the scope and pervasiveness of American global power today are unique. Not only does the United States control all the world's oceans, its military legions are firmly perched on the western and eastern extremities of Eurasia ... American vassals and tributaries, some yearning to be embraced by even more formal ties to Washington, dot the entire Eurasian continent ... American global supremacy is ... buttered by an elaborate system of alliances and coalitions that literally span the globe.[57]

Besides the military foundation, there are significant non-military international institutions backed by American financing and diplomacy (like the United Nations and WTO). The United States invested heavily in programs such as the Marshall Plan and in the reconstruction of Japan, economically cementing defense ties that owed increasingly to the establishment of the Iron Curtain/Eastern Bloc and the widening of the Cold War.

Being in the best position to take advantage of free trade, culturally indisposed to traditional empires, and alarmed by the rise of communism in China and the detonation of the first Soviet atom bomb, the historically non-interventionist US also took a keen interest in developing multilateral institutions which would maintain a favorable world order among them. The International Monetary Fund and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), part of the Bretton Woods system of international financial management was developed and, until the early 1970s, the existence of a fixed exchange rate to the US dollar. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was developed and consists of a protocol for normalization and reduction of trade tariffs.

With the fall of the Iron Curtain, the demise of the notion of a Pax Sovietica, and the end of the Cold War, the US maintained significant contingents of armed forces in Europe and East Asia. The institutions behind the Pax Americana and the rise of the United States unipolar power have persisted into the early 21st century. The ability of the United States to act as "the world's policeman" has been constrained by its own citizens' historic aversion to foreign wars.[58] Though there have been calls for the continuation of military leadership, as stated in "Rebuilding America's Defenses":

The American peace has proven itself peaceful, stable, and durable. It has, over the past decade, provided the geopolitical framework for widespread economic growth and the spread of American principles of liberty and democracy. Yet no moment in international politics can be frozen in time; even a global Pax Americana will not preserve itself. [... What is required is] a military that is strong and ready to meet both present and future challenges; a foreign policy that boldly and purposefully promotes American principles abroad; and national leadership that accepts the United States' global responsibilities.[59]

This is reflected in the research of American exceptionalism, which shows that "there is some indication for [being a leader of an 'American peace'] among the [US] public, but very little evidence of unilateral attitudes".[8] Resentments have arisen at a country's dependence on American military protection, due to disagreements with United States foreign policy or the presence of American military forces.

In the post-communism world of the 21st-century, the French Socialist politician and former Foreign Minister Hubert Védrine describes the US as a hegemonic hyperpower, while the US political scientists John Mearsheimer counter that the US is not a "true" hegemony, because it does not have the resources to impose a proper, formal, global rule; despite its political and military strength, the US is economically equal to Europe, thus, cannot rule the international stage. Several other countries are either emerging or re-emerging as powers, such as China, Russia, India, and the European Union.

In 1998, American political author, Charles A. Kupchan, described the world order "After Pax Americana"[60] and the next year "The Life after Pax Americana".[61] In 2003, he announced "The End of the American Era".[62] In 2012, he projected: "America's military strength will remain as central to global stability in the years ahead as it has been in the past."[63]

The Russian analyst Leonid Grinin argues that at present and in the nearest future Pax Americana will remain an effective tool of supporting the world order since the US concentrates too many leadership functions which no other country is able to take to the full extent. Thus, he warns that the destruction of Pax Americana will bring critical transformations of the World-system with unclear consequences.[64]

American political analyst Ian Bremmer argued that with the election of Donald Trump and the subsequent rise in populism in the west,[65][66] as well as US withdrawal from international agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, NAFTA, and the Paris Climate Accords, that the Pax Americana is over.[67]

American writer and academic Michael Lind stated that the Pax Americana withstood both the Cold War and the post-Cold War era, and "today's Second Cold War has strengthened rather than weakened America's informal empire," at least for now.[68]

Comparison with Pax Romana

In 1914, an Italian Historian, Guglielmo Ferrero, published Ancient Rome and Modern America: A Comparative Study of Morals and Manners. The title is misleading because the work does not pertain specifically to the United States. Instead, it compares Rome and what Ferrero labels the "New World" and broadens the discussion to modern civilization in general.[69] However, Ferrero's pioneering comparison echoed in the 1961 article by Mason Hammond, titled "Ancient Rome and modern America reconsidered."[70] Highly critical of the use of the past for the present, he still associated: "The modern world, like the Mediterranean world of the First century BC, faces a choice between self-annihilation... or of unification and peace... Rome of the second century BC and the United States of today face without adequate preparation the responsibilities of world dominance and the dilemma of how to reconcile recognition of the sovereignty of other states with national security."[71]

Hammond considered five moments in Roman history which offer tempting similarities to the American present and suggested the differences which "render such parallels deceptive."[72] Two of his differences refer to the parallel between Rome in 150 BC and the United States in 1960. First, representative federalism today offers for international rivalries an alternative solution to Pax Americana. "Rome moved toward imperialistic control; the United States can still hope for a cooperative federal solution through the United Nations." Unwilling to trust the lessons of history, Hammond bet on the utopian idea of world federalism. Second, the world is bipolar and it would be "foolish to equate Antiochus the Great of Syria in the 190s BC or Parthia in the 150s as rivals to Rome with Russia as a rival to the United States" because Russia is more formidable.[73] What Hammond called "representative federalism" remains where it was in his days, but thirty years after he published his parallels, Pax Americana leaped relatively to Pax Sovietica. The parallel proved to be "deceptive" indeed but in the opposite sense.

Writing in 1945, Ludwig Dehio remembered that the Germans used the term Pax Anglosaxonica in a sense of Pax Americana since 1918 and discussed the possibility of a Pax Anglosaxonica as a world-wide counterpart to the Pax Romana.[25] The United States, Dehio associates on the same page, withdrew to isolation on that occasion. "Rome, too, had taken a long time to understand the significance of her world role."

With the outbreak of World War II, British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, resolved that England would win the Second World War too as Rome had won the Second Punic War. Hitler disagreed: history has not yet determined who shall play Rome and who shall play Carthage in this case.[74] The War fast took a clear turn towards what the contemporary Germans feared as the fatal Pax Anglosaxonica. In 1943, Hitler tried to encourage his team: "They will never become Rome. America will never be the Rome of the future."[75] The same year, however, Hitler's compatriot and the founder of the Paneuropean Union, Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, whom Hitler called "cosmopolitan bastard,"[76] projected a new "Pax Romana" based on the preponderant US air power:

During the third century BC the Mediterranean world was divided on five great powers – Roma and Carthage, Macedonia, Syria, and Egypt. The balance of power led to a series of wars until Rome emerged the queen of the Mediterranean and established an incomparable era of two centuries of peace and progress, the 'Pax Romana' ... It may be that America's air power could again assure our world, now much smaller than the Mediterranean at that period, two hundred years of peace ... This is the only realistic hope for a lasting peace.[77]

Soon many scholars found that what Coudenhove-Kalergi called the "only realistic hope for peace" is coming true. In 1953, British Classicist Gilbert Murray encouraged that across the Atlantic is waiting a "greater Rome" which can establish world peace or at least maintain Europe in an "ocean of barbarism" as Rome maintained Hellas.[78] In the mid-1960s, some scholars concluded that the United States had outstripped the Soviet Union beyond the bipolar model and instead looked to the model of Rome.[79] One of those scholars, George Liska, argued that historical superstates in general and the Roman Empire in particular rather than the recent colonial empires have relevance for the contemporary US foreign policy.[80]

Prefacing his Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire in 1976,[81] Pentagon employee Edward Luttwak stressed that the United States pursues similar to Rome goals, faces a similar kind of resistance, and hence must apply a similar strategy. In the late 1990s,[82] Pentagon initiated new research on "military advantage in history" and how to keep it. Of four empires they selected, Rome was emphasized as the most relevant model for the contemporary United States.[83] The "whole bunch" of copies went out to the government.[82] A decade later, former NSC employee, Carnes Lord, compared US combatant commanders, Roman proconsuls, British colonial officials, Persian satraps and Spanish viceroys. He found the American version most similar to the Roman proconsular model.[84]

While Pentagon and NSC employees turned into Roman Historians, Roman Historian Arthur M. Eckstein proceeded in the reverse direction. He noted that the theoretical framework of hierarchy, unipolarity, and empire as political scientists have defined these terms is a procedure rarely pursued among scholars of Mediterranean antiquity[85] and decided to fill the gap. Eckstein presented his subject in terms of the 20th-century International Relations. The five-year (196–192 BC) diplomatic confrontation between Rome and Antiochus III was a classic contest between the two superpowers in a "bipolar system."[86] The confrontation turned into war and in 189 BC Rome defeated Antiochus. This victory resulted in an unprecedented for the Mediterranean world unipolar moment with Rome established as a "unipolar hegemon." There remained only one political and military focus, only one preponderant power. "Rome was now the sole remaining superpower.” A unified "unipolar system" stretched from Spain to Syria.[87]

Anti-imperialist empire is not a modern invention. Initially, Rome had appeared in the East as an anti-imperialist power – the champion of the weaker states against the aggression of the great powers of Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus III.[88] Eckstein's student, Paul Burton, adds that Achaean League statesman Lycortas, father of Polybius, interpreted the Roman foreign policy in words that might sound familiar to the critics of US foreign policy: The message the Romans are sending by criticizing the Achaeans is that "freedom, in the Roman mind, is also empire" (Livius 39.36.5 – 37.17).[89]

But Eckstein cared to provide the contemporary world with an emergency exit from Pax Americana. The Roman achievement of unipolarity was only one step along the spectrum of interstate relations that leads towards empire. And unipolarity, even when once achieved, can nevertheless be reversed. Historically this has frequently occurred and in the late 2000s the United States is discovering that unipolarity is unstable.[90]

Joseph Nye titled his 2002 article "The New Rome Meets the New Barbarians".[91] His book of the same year he opens: "Not since Rome has one nation loomed so large above the others."[92] And his 1991 book he titled Bound to Lead.[93] Leadership, translated into Greek, renders hegemony; an alternative translation is archia – Greek common word for empire. Decline, he writes, is not necessarily imminent. "Rome remained dominant for more than three centuries after the peak of its power ...[94]

The Pax Americana motif and its Roman parallel reached their peak in the context of the 2003 Iraq War. Comparing the United States to the Roman Empire has become somewhat of a cliché.[95][96] Jonathan Freedland observed:

Of course, enemies of the United States have shaken their fist at its "imperialism" for decades ... What is more surprising, and much newer, is that the notion of an American empire has suddenly become a live debate inside the United States Accelerated by the post-9/11 debate on America's role in the world, the idea of the United States as a 21st-century Rome is gaining a foothold in the country's consciousness.[97]

The New York Review of Books illustrated a 2002 piece on US might with a drawing of George Bush togged up as a Roman centurion, complete with shield and spears.[98] Bush's visits to Germany in 2002 and 2006 resulted in further Bush-as-Roman-emperor invective appearing in the German press. In 2006, freelance writer, political satirist, and correspondent for the left-leaning Die Tageszeitung, Arno Frank, compared the spectacle of the visit by Imperator Bush to "elaborate inspection tours of Roman emperors in important but not completely pacified provinces – such as Germania".[99] In September 2002, Boston's WBUR-FM radio station titled a special on US imperial power with the tag "Pax Americana".[100] The phrase "American Empire" appeared in one thousand news stories over a single six-month period in 2003.[101] A 2009 Google search yielded policy analyst Vaclav Smil 22 million hits for "America as a new Rome", and 23 million for "American Empire." Intrigued, Smil titled his 2010 book by what he intended to explain: Why America Is Not a New Rome.[102] The volume of the Rome-US comparisons made a bewildering impression on reviewers: "As the trickle turns into a flood, it is impossible to keep up with the many articles, books, internet sites, and documentaries that pose the comparison. Even after 2009... the number of works about Rome and the USA shows no sign of abating."[103]

Two Classicists, Paul J. Burton[104] and Eric Adler, decided that the volume of comparisons between America and Rome requires research of its own. Adler's comparison of comparisons revealed that most interventionists dissociate America from Rome while most critics of US interventions emphasize similarities between the two. The same he finds true for the Edwardian and Victorian debates regarding the British Empire. Isolationists use the polemical value of the "New Rome" to "shock" the reader while interventionists offer the same reader a therapy by distinguishing Rome from America. Adler also observed that many notable authors are more interested in expressing their opinion about recent US foreign policy rather than offering a nuanced interpretation of Roman history checked against primary sources. Instead, from secondary sources they select elements fitting their line and disregard whether these elements are from the republican Rome, or imperial Rome, or even the Byzantine Empire.[105]

Like Smil, Classicist and military Historian Victor Davis Hanson dissociates the United States from Rome. The U.S. does not pursue world domination, but maintains worldwide influence by a system of mutually beneficial exchanges.[106] He dismisses the notion of an American Empire altogether, with a mocking comparison to historical empires: "We do not send out proconsuls to reside over client states, which in turn impose taxes on coerced subjects to pay for the legions. Instead, American bases are predicated on contractual obligations — costly to us and profitable to their hosts. We do not see any profits in Korea, but instead accept the risk of losing almost 40,000 of our youth to ensure that Kias can flood our shores and that shaggy students can protest outside our embassy in Seoul."[106]

The existence of "proconsuls", however, has been recognized by many since the early Cold War. In 1957, French Historian Amaury de Riencourt associated the American "proconsul" with "the Roman of our time."[107] Expert on recent American history, Arthur M. Schlesinger, detected several contemporary imperial features, including "proconsuls." Washington does not directly run many parts of the world. Rather, its "informal empire" was one "richly equipped with imperial paraphernalia: troops, ships, planes, bases, proconsuls, local collaborators, all spread wide around the luckless planet."[108] "The Supreme Allied Commander, always an American, was an appropriate title for the American proconsul whose reputation and influence outweighed those of European premiers, presidents, and chancellors."[109] U.S. "combatant commanders ... have served as its proconsuls. Their standing in their regions has usually dwarfed that of ambassadors and assistant secretaries of state."[110][111][112]

Andrew J. Bacevich in his 2002 book about American Empire titled a chapter “Rise of the proconsuls,” where he identifies a new class of uniformed proconsuls presiding over vast “quasi-imperial” domains who emerged in the 1990s.[113] In September 2000, Washington Post reporter Dana Priest published a series of articles whose central premise was Combatant Commanders' inordinate amount of political influence within the countries in their areas of responsibility. They "had evolved into the modern-day equivalent of the Roman Empire's proconsuls—well-funded, semi-autonomous, unconventional centers of U.S. foreign policy."[114] A book, titled America's Viceroys, responds to Priest, claiming that US Combatant Commanders pose no threat of marching on Washington while Roman proconsuls “always presented” such threat.[115][116] Many Roman historians however reduce the period of the threat from “always” to the last century of the Republic (133-31 BC). One of most honorable Roman proconsuls who won for Rome supremacy over the Mediterranean, Scipio Africanus, was unsuccessful in the 184 BC campaign for the censorship and retired from politics. Founded c. 509 BC, the Republic still firmly controlled its proconsuls. Stephen Wrage precludes future complications with Combatant Commanders,[117] while some Roman historians are more cautious, supposing that the United States might be in the Roman sequence "somewhere between the great wars of conquest [202-146 BC] and the rise of the Caesars."[118][119][120]

Carnes Lord observes that since the 2000s, the notion that the Combatant Commanders are in effect the “proconsuls” of a new American Empire has become a standard trope in the literature on American foreign policy.[121] Harvard professor Niall Ferguson calls the regional combatant commanders, among whom the whole globe is divided, the "pro-consuls" of this "imperium."[122] Günter Bischof calls them "the all powerful proconsuls of the new American empire. Like the proconsuls of Rome they were supposed to bring order and law to the unruly and anarchical world."[123] The Romans often preferred to exercise power through friendly client regimes, rather than direct rule: "Until Jay Garner and L. Paul Bremer became U.S. proconsuls in Baghdad, that was the American method, too".[124]

Carnes Lord devoted a book to comparison between the Roman proconsuls, British colonial officials and US Combatant Commanders. The latter for him also associate with the Persian satraps and Spanish viceroys. He found the American version most similar to the Roman proconsular model. As they contributed importantly to the policy on the marches of empire, all of them qualify as proconsuls in proper sense of the term. With all due qualification, he confessed, his study is about imperial governance in the imperial periphery.[121]

Another distinction of Victor Davis Hanson—that US bases, contrary to the legions, are costly to America and profitable for their hosts—expresses the American view. The hosts express a diametrically opposite view. Japan pays for 25,000 Japanese working on US bases. 20% of those workers provide entertainment: a list drawn up by the Japanese Ministry of Defense included 76 bartenders, 48 vending machine personnel, 47 golf course maintenance personnel, 25 club managers, 20 commercial artists, 9 leisure-boat operators, 6 theater directors, 5 cake decorators, 4 bowling alley clerks, 3 tour guides and 1 animal caretaker. Shu Watanabe of the Democratic Party of Japan asks: "Why does Japan need to pay the costs for US service members' entertainment on their holidays?"[125] One research on host nations support concludes that the general trend of the South Korean and Japanese alliance burden sharing is towards increase.[126] Increasing the "economic burdens of the allies" is one of the major priorities of President Donald Trump.[127]

Classicist Eric Adler notes that Hanson earlier had written about the decline of the classical studies in the United States and insufficient attention devoted to the classical experience. "When writing about American foreign policy for a lay audience, however, Hanson himself chose to castigate Roman imperialism in order to portray the modern United States as different from—and superior to—the Roman state."[128] As a supporter of a hawkish unilateral American foreign policy, Hanson's "distinctly negative view of Roman imperialism is particularly noteworthy, since it demonstrates the importance a contemporary supporter of a hawkish American foreign policy places on criticizing Rome."[128]

Scholars list many additional parallels with the early Pax Romana (especially between 189 BC when the supremacy over the Mediterranean was won and the first annexation in 168 BC). By contrast to other empires, the early Pax Romana did not impose regular taxation on other states.[129][130] The first good evidence of such a taxation comes from Judea as late as 64 BC.[131] Client states made irregular military or economic contributions in case of the hegemonic campaigns, as is the case under the Pax Americana.[132]

Formally, client states remained independent and very seldom were called "clients". The latter term became widely used only in the late medieval period. Usually, other states were called "friends and allies" – a popular expression under the Pax Americana. Arnold J. Toynbee stressed the similarity of the US alliances with the Roman client system[133] and Ronald Steel cited Toynbee's parallel at length in his book, titled Pax Americana.[134] Nominally independent allies were offered Roman or US protection which, according to Peter Bender, meant their control and limit on other states' sovereignty.[135] Bender, in his 2003 article "America: The New Roman Empire", summarized: "When politicians or professors are in need of a historical comparison in order to illustrate the United States' incredible might, they almost always think of the Roman Empire."[136] The article abounds with analogies. The Romans similarly were isolationists until they expanded outside of Italy.[137] The factor for the overseas engagement is the same in both cases: the seas or oceans ceased to offer protection, or so it seemed:

Rome and America both expanded in order to achieve security. Like concentric circles, each circle in need of security demanded the occupation of the next larger circle. The Romans made their way around the Mediterranean, driven from one challenger to their security to the next. The struggles ... brought the Americans to Europe and East Asia; the Americans soon wound up all over the globe, driven from one attempt at containment to the next. The boundaries between security and power politics gradually blurred. The Romans and Americans both eventually found themselves in a geographical and political position that they had not originally desired, but which they then gladly accepted and firmly maintained.[138]

Both Rome and the United States claimed the unlimited right to render their enemies permanently harmless." Postwar treatments of Carthage, Macedon, Germany and Japan are similar. "When they later extended their power to overseas territories, they shied away from assuming direct control wherever possible." In the Hellenistic world, Rome withdrew its legions after three wars and instead settled for a role of all-powerful patron and arbitrator.[139] "World powers without rivals are a class unto themselves. They ... are quick to call loyal followers friends, or amicus populi Romani. They no longer know any foes, just rebels, terrorists, and rogue states. They no longer fight, merely punish. They no longer wage wars but merely create peace. They are honestly outraged when vassals fail to act as vassals."[140] Zbigniew Brzezinski comments on the latter analogy: "One is tempted to add, they do not invade other countries, they only liberate."[141]

Some scholars deemed Mithridates' massacre of Roman citizens in 88 BC Rome's "9/11 moment" and described the ways in which the vicissitudes of contemporary Pax Americana are reminiscent of Rome's reaction to Mithridates' revolt.[142][143] Robert Fisk used the association to claim that Pax Romana was more cruel than Pax Americana: Following the massacre, the Romans "crucified their enemies to extinction. Human rights knew no dimensions in ancient Rome."[144] Alternatively, Max Ostrovsky defines such conclusions as pre-determined and unrelated to what really happened. No mass crucification occurred. Having defeated Mithridates in 84 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla concluded with him peace and recognized him as friend and ally of Rome. No modern ruler would survive having massacred 80,000 American citizens, neither in power nor physically.[145] On the occasion, the tolerance of Pax Romana appears exaggerated by both ancient and modern standards. Cicero (De Imperio Cn. Pompei) wondered how Mithridates was left upon throne and allowed to initiate two more anti-Roman wars. Only after the Third Mithridatic War in 64 BC Pompey finally put an end to his kingship and annexed the rogue Kingdom.

Besides the books of Vaclav Smil and Peter Bender, a book completely devoted to the comparison between Rome and the United States is The Empires of Trust by Roman Historian Thomas F. Madden.[146] Madden outlines numerous parallels, many in agreement with Bender, such as beginning of both Empires as frontier societies and following isolationist policy, their later pattern of defensive imperialism, and allying other states rather than conquering them. Besides causes and patterns, he devotes much attention to the analogous results of Pax Romana and Pax Americana. The elimination of external threat leads to decline in internal social harmony.

The Roman synchronous establishment of the empire and the fall of the republic is causally linked by almost all writers on the subject, ancient and modern, and the thesis is often applied to the United States. US increasing imperialism and expansionism, modern experts warn, would exert a similar impact. The warning was traditionally repeated by anti-imperialists and isolationists from Mark Twain to Robert A. Taft to Patrick Buchanan and grew louder with the increased intervention during the War on Terror from such authors as Chalmers Johnson, Robert Merry, and Michael Vlahos.[147] The distinction of Madden's research is the focus on Pax. The new and bitter civil strife that erupted in Rome and led to the fall of the Republic was a by-product of Pax which paradoxically bears fierce internal divisions. The Romans remained a closely knit group so long as they continued to have powerful outside enemies – so long as the collective focus of their lives was the defense and preservation of their society.[148]

The powerful outside enemies were eliminated by 146 BC. And in 133 BC, violence broke on the Capitoline Hill in Rome. For the first time, the people did not defer to the Senate. And perhaps not anymore. Law was dispensed with and blood began to flow. Romans were killing Romans.[149]

Both classics[150] and modern historians stressed the absent external threat as the factor of civil wars in the 1st century BC followed by the fall of the Republic. But Madden seems to be the first scholar to apply the thesis to the United States: "Do the same dangers await America?"[151] Writing before the 2021 Capitol attack, he reflects:

Capitol Hill was the city's highest and most revered of the seven hills that made up Rome. Of course, Washington has a Capitol Hill too, named after the Roman one, and which has seen its own share of political fights. But not like this... No blood has yet flowed on America's Capitol Hill, but the Pax Americana is still young.[152]

In 146 BC, thirteen years before the first outbreak of civil violence, Rome had eliminated two more external threats (from Carthage and Greece). The United States lost its last grave (Soviet) external threat in 1991. Supposing that we might be in the Roman sequence, where 146 BC corresponds to AD 1991, Madden asks whether the United States has reached the level of Pax that Rome had achieved by 146 BC.[153] His estimation is either yes or very close,[154] but either way external threats will remain too small to wield the pre-1991 national unity.[151]

Thus, America is likely to repeat the Roman sequence and, though writing before 2020, he finds that indeed since 1991 the Americans, like the Romans since 146 BC, have been losing their internal harmony. Without external threats, he says, it is not surprising that we can detect the same turn inward in the United States as well. The dynamics that had bound Americans so closely together gave way to those that bound them together into smaller groups, such as red states and blue states.[155]

Political rivalries under the Pax Romana became fierce – so fierce that they undermined the fabric of the Republic. The Roman experience suggests that a republic cannot survive such a turmoil. But it was neither the Empire that was at stake, nor the Pax Romana that it brought. Those would remain secure for centuries. It was, instead, the republican form of government that fell. Hence, in worst case, Pax Americana would continue under imperial government.[151]

Remove ads

See also

- American Tianxia

- American Imperialism

- Anti-communism

- Bretton Woods system

- Bush Doctrine

- Cold War (1985–1991)

- Neoconservatism

- New world order

- Overseas interventions of the United States

- Pax Americana and the Weaponization of Space

- Pax Russica

- Platt Amendment

- Reagan Doctrine

- Timeline of United States military operations

- Truman Doctrine

- War on Terror

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads