Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Puquina language

Extinct language of South America From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

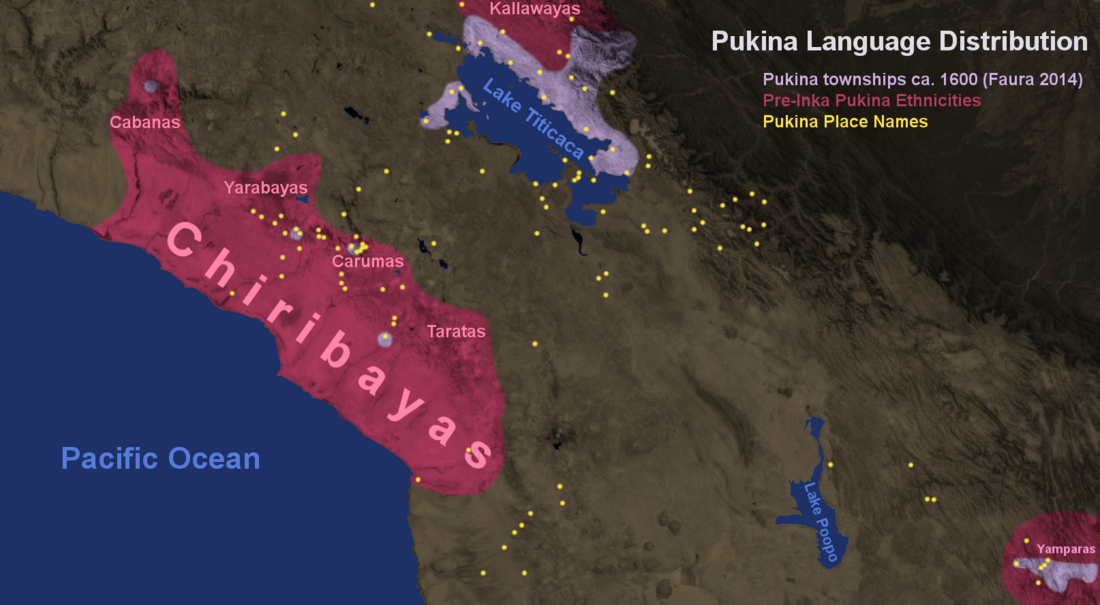

Puquina (or Pukina) is an extinct language once spoken by a native ethnic group in the region surrounding Lake Titicaca (Peru and Bolivia) and in the north of Chile. It is often associated with the culture that built Tiwanaku.

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (December 2025) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (February 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

A Puquina substrate can be found in the Quechuan and Spanish languages spoken in the south of Peru, mainly in Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna, as well as in Bolivia. There also seem to be remnants in the Kallawaya language, which may be a mixed language formed from Quechuan languages and Puquina. (Terrence Kaufman (1990) finds the proposal plausible.[1])

Sometimes the term Puquina is used for the Uru language, which is distinctly different.

Remove ads

Classification

Summarize

Perspective

Puquina has been considered an unclassified language, since it has not been proven to be firmly related to any other language in the Andean region. A relationship with the Arawakan languages has long been suggested, based solely on the possessive paradigm (1st no-, 2nd pi-, 3rd ču-), which is similar to the proto-Arawakan subject forms (1st * nu-, 2nd * pi-, 3ª * tʰu-). Recently Jolkesky (2016: 310-317) has presented further possible lexical cognates between Puquina and the Arawakan languages, proposing that this language belongs to the putative Macro-Arawakan stock along with the Candoshi and the Munichi languages. However, such a hypothesis still lacks conclusive scientific evidence.

In this regard, Adelaar and van de Kerke (2009: 126) have pointed out that if in fact the Puquina language is genetically related to the Arawakan languages, its separation from this family must have occurred at a relatively early date; the authors further suggest that in such a case the location of the Puquina speakers should be taken into account in the debate over the geographic origin of the Arawakan family. Such consideration was taken up by Jolkesky (op. cit., 611-616) in his archaeo-ecolinguistic model of diversification of the Macro-Arawakan languages. According to this author, the proto-Macro-Arawakan language would have been spoken in the Middle Ucayali River Basin during the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE and its speakers would have produced in this region the Tutishcainyo pottery.

Remove ads

Phonology

Consonants

- /h/ may also be heard as a uvular fricative [χ].

- /ʎ/ may also be heard as a voiced palatal affricate [ɟʎ̝].

Vowels

- Sounds [o, u] may either be heard as fluctuates of each other, or as separate phonemes /o/ and /u/.[2]

Remove ads

Vocabulary

Numerals

Pronouns

Loukotka (1968)

Proposed Inca affiliation

Summarize

Perspective

The linguist Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino proposed that "Qhapaq Simi", the cryptic language of the nobility of the Inca Empire, was closely related to Puquina, and that Runa Simi (Quechuan languages) were spoken by commoners; this proposal is known as the "Puquinist Hypothesis"[5]

The prominent linguist Alfredo Torero, a scholar of the Puquina language, has debunked and refuted of the "Puquinist hypothesis". In his last book, "Languages of the Andes," published in 2002, he argued the following:[6]

Following these replies and other arguments of ours regarding the Quechua-Aru relationship that we put forth in a 1998 work, Rodolfo Cerrón, in an almost complete turn, assumed our thesis months later, but wrapping himself - as is usual in him - in a smokescreen in the form of 'criticisms' of our and Szeminski's interpretations, 'criticisms' so misplaced and so easily refutable, that they seemed to be driven by profound ignorance and phobias (Cerrón, 1998).

In a new article, "Following the Footsteps of the Cuzco Aymara" (1999), our former disciple merely reiterates his arguments from a year earlier, so our observations will refer to his first article.

To measure (if possible) the magnitude of the missteps it makes, we reproduce here the analysis we made of the song in 1994, and some notes with which we supported, then and now, our conviction that we are facing a sample of an Aru language, and not a Puquina one.

— Alfredo Torero Fernández de Córdova, Languages of the Andes

Torero is convinced that the "particular language of the Incas" was a variant of the Aru or Aymara language family; his main arguments are the following:[6]

a) even if it had been in Puquina, which at the time was the 'third general language of Peru' and reached the gates of Cuzco, it would not have been secret either;

b) Murúa's observation, if we take it as well established, is a guarantee to rule out the Puquina, since the Mercedarian friar taught doctrine in the Altiplano and at the foot of Puquina populations, whose speech he would have recognized;

c) In the song, we had detected "an aru language" or an Aymara variety "with divergent features," not -let's say- Bertonio's Lupaca Aymara. Now the situation is clearer: the divergence of this 'particular Inga language' with respect to Aymara had reached a degree similar to that of the Cauquis languages currently used in Tupe and Cachuy, Yauyos, and formerly in Huarochirí, or to that of the "hahuasimis" of Lucanas or the "Chumbivilca language" of the 16th century, none of which were even recognized as similar to Aymara, despite belonging to the same family.

— Alfredo Torero Fernández de Córdoba, Languages of the Andes

Moulian et al. (2015) argue that Puquina language influenced Mapuche language of southern Chile long before the rise of the Inca Empire.[7] This areal linguistic influence may have started with a migratory wave arising from the collapse of the Tiwanaku empire around 1000 CE.[7][8]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads