Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

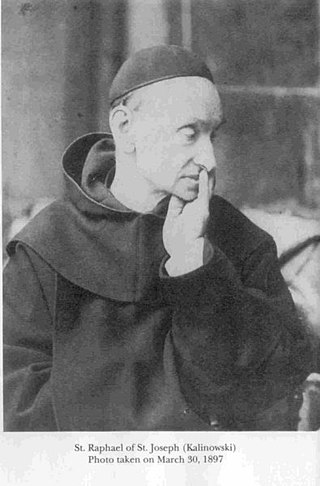

Raphael Kalinowski

Polish friar and saint (1835–1907) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Raphael of Saint Joseph Kalinowski OCD (1 September 1835 – 15 November 1907) was a Polish Carmelite, social activist, participant in the January Uprising, and a saint of the Catholic Church. Before his conversion, he served in the Imperial Russian Army, fought in the January Uprising in Lithuania and was exiled to Siberia.

He was born as Józef Kalinowski in Vilnius into a noble family bearing the Kalinowa coat of arms. After completing his education at the Institute for Nobles in Vilnius, he became a military engineer in the Russian army, where he engaged in pro-independence conspiracy. After the outbreak of the January Uprising, he left the army; he did not take part in the fighting himself, but supported the insurgents. For this activity, in 1864 he was sentenced to death, later commuted to ten years of hard labor in Siberia.

During his exile he underwent a religious conversion and became a devout Catholic. After returning in 1874, he settled in Warsaw. In 1877 he entered the Carmelite novitiate in Graz, taking the religious name Raphael of Saint Joseph Kalinowski. He professed his solemn vows in 1881 and settled in the monastery in Czerna near Kraków, where he soon became prior. He gained renown as a confessor, theologian, translator, and founder of monastic houses.

He died on 15 November 1907 in the odour of sanctity. His informative process was opened in 1934. On 22 June 1983 in Kraków, John Paul II beatified Raphael Kalinowski, and on 17 November 1991 in Rome, canonized him. The liturgical memorial of St. Raphael Kalinowski is celebrated on 20 November. He is the patron saint of Catholics in Siberia, as well as soldiers, engineers, and railway workers.

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Childhood

Raphael was born Józef Kalinowski to a noble szlachta family in the city of Vilnius. He was born after the failed November Uprising, which failed to liberate the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the wider Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from the Russian partition.

He was the second son of Andrzej Kalinowski (1805–1878), an assistant superintendent professor of mathematics at the Institute for Nobles in Vilnius. His mother, Józefa Połońska, also a noblewoman, Leliwa coat of arms died a few months after he was born, leaving him and his older brother Wiktor (1833–1880) without a mother. His father then married Józefa's sister Wiktoria Połońska, and had three more children: Emilia (1840–1897), Gabriel Hilary (1840–1898) and Karol (1841–1877).[1] After Wiktoria died in 1845, Andrew married again, this time to Zofia Puttkamer, daughter of Maryla Wereszczak (famous at the time for being written about by Adam Mickiewicz) and Wawrzyniec Puttkamer, and had with her four more children: Maria (1848–1878), Aleksander (1851–1920), Monika (1855–1868) and Jerzy (1859–1930).

From the age of 8, Kalinowski attended the Institute for Nobles in Vilnius, and graduated with honors in 1850.[2] He next attended the Institute of Agriculture at Hory-Horki, near Orsha.

Military career

The Russians strictly limited opportunities for further education, so in 1853 he enlisted in the Imperial Russian Army and entered the Nicholayev Engineering Academy. The Army promoted him to Second Lieutenant in 1856. In 1857 he worked as an associate professor of mathematics, and from 1858 to 1860, he worked as an engineer who helped design the Odessa-Kiev-Kursk railway.

In 1862 the Imperial Russian Army promoted him to captain and stationed him in Brest (in modern-day Belarus), but he still sympathized with the Poles.

January Uprising

When a wave of patriotic and religious demonstrations swept the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1861–1862, Kalinowski distanced himself from them, dismissing them as "sentimental piety."[3] Kalinowski met in Warsaw with Piotr Kobylański, a future member of the Polish National Government, whom he then considered an extreme demagogue, which is one of the explanations offered as to why he became disaffected with the Reds and did not engage deeply in the underground resistance, despite attending secret meetings.[4] He was also critical of the idea of relying on the intervention of Western countries in the Polish case and was generally against initiating an uprising.[5] Knowing that the uprising would break out and fearing that the Brest Fortress would be used in military operations against the insurgents, he decided to leave the Russian army and work again in railway construction.[5]

When the January Uprising broke out, Józef Kalinowski was in Brest-Litovsk.[6] Only by chance did he avoid having to engage in armed combat against his compatriots participating in the uprising.[7] Fearing being called upon to fight the insurgents, Kalinowski, an officer in the tsarist army with the rank of captain, resigned from the army and received his resignation on May 17, 1863.[8][9] While in Warsaw, he provided the insurgent authorities with plans of Russian fortresses and received an offer from Józef Gałęzowski to take up an executive position in the Lithuanian insurgent authorities.[10][11]

At the end of May he went to Vilnius and, although he was critical of those who had instigated the January Uprising, he took over the War Department of the Executive Department in Lithuania with the stipulation that he would not conduct revolutionary propaganda and would not organize a revolutionary faction of the uprising.[12] He was only involved in the military aspect of the uprising, trying to organize armed forces in Lithuania, although he himself did not take part in the fighting.[13][14] He also did not agree to the issuing and execution of death sentences on a large scale.[15] At the same time, he started working as a secondary school teacher, teaching surveying.[16]

Once in Lithuania, Kalinowski realized that the insurgents' armed forces were small, undisciplined, scattered, and poorly armed, that the insurgents' commanders operated alone, that contact with them was very difficult, that attempts to deliver weapons from East Prussia were unsuccessful, and that, on top of all this, information about the fighters was uncertain.[17] Many military decisions did not reach the insurgents at all.[18] In his report to the War Department of the National Government, he considered the case of an armed uprising in Lithuania hopeless and therefore opposed the expansion of military operations, as it would only result in futile sacrifices.[19] Soon the remaining members of the Executive Branch were arrested.[19] In December 1863, Kalinowski asked the head of the Lithuanian uprising authorities to notify the National Government in Warsaw that the uprising in Lithuania had collapsed and ordered the cessation of arms deliveries in order to minimize Russian repressive actions.[20][21] He also refrained from any action.[22]

On August 15, 1863, fulfilling a promise made to his 14-year-old sister, he went to confession for the first time in nine years.[23][24][25] From then on, he attended Holy Mass daily, made weekly confession, and became interested in theology.[26][27] Shortly thereafter, he first conceived the idea of joining a religious order (the Capuchins), but had to abandon these plans after becoming involved in the underground uprising.[28] In the 1870s, in a letter to his stepmother, Zofia Kalinowska, who was painfully affected by her stepson's religious indifference, he wrote from exile that he owed his conversion, among other things, to her.[29]

On the night of March 24-25, 1864, Kalinowski was arrested in his parents' apartment and placed under investigation.[30] He was caught because one of the insurgents involved in the uprising's leadership revealed information about him in a Russian prison to an associate of the head of the insurgent leadership in Lithuania, who was in the employ of the Russians.[31] Kalinowski initially denied participating in the January Uprising, but fearing that this would intensify the investigation within his immediate circle and bring dire consequences to his comrades, he decided to confess and take as much blame as possible. On April 9, 1864, he testified, but provided only the names of those who had already been arrested or had left Lithuania.[32][33] On May 28, he was court-martialed and pleaded guilty, but cited the mitigating circumstance that he had sought to curtail the insurgent activities as early as December 1863.[15] On June 2, 1864, the death sentence was passed, but thanks to the efforts and connections of the family, it was reviewed, and on July 2 of that year, a sentence of 10 years' hard labor was imposed, along with the deprivation of nobility and state privileges.[a][34] The sentence was allegedly also mitigated by a letter sent by Kalinowski to Mikhail Muravyov, which made a great impression on the Governor-General of Vilnius; he was also convinced that executing a death sentence on a person popularly considered a saint would make him a martyr in the eyes of the Poles.[35][36][37]

Siberian exile

On 24 March 1864, Russian authorities arrested Kalinowski and in June condemned him to death by firing squad. His family intervened, and the Russians, fearing that their Polish subjects would revere him as a political martyr, commuted the sentence to 10 years[38] in katorga, the Siberian labor camp system. They forced him to trek overland to the salt mines of Usolye-Sibirskoye near Irkutsk, Siberia, a journey that took nine months.[2] Very few survived the forced march to slave labour in Siberia, but Raphael was sustained by his faith and became a spiritual leader to the prisoners.

Three years after arriving in Usolye, Kalinowski moved to Irkutsk. In 1871/1872 he did meteorological research for the Siberian subdivision of the Russian Geographical Society. He also participated in research expedition of Benedykt Dybowski to Kultuk, on the shore of Lake Baikal. Authorities released him from Siberia in 1873 but exiled him from Lithuania; he then moved to Paris, France.

Czartoryski tutor

Kalinowski returned to Warsaw in 1874, where he became a tutor to 16-year-old Prince August Czartoryski. The prince was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1876, and Kalinowski accompanied him to various health destinations in France, Switzerland, Italy, and Poland.[2] Kalinowski was a major influence on the young man (known as "Gucio"), who later became a priest and was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2004.

Later Kalinowski decided to travel to the city of Brest where he began a Sunday school at the fortress in Brest-Litovsk where he was a captain, he became increasingly aware of the state persecution of the church, and of his native Poles.

Carmelite friar and priest

In 1877 Kalinowski was admitted as a postulant to the Carmelite priory in Linz, and where he was given the religious name Raphael of St. Joseph on his investiture.

Kalinowski was ordained a priest at Czerna in 1882 by Bishop Albin Dunajewski, and in 1883 he became prior of the convent at Czerna. Kalinowski founded multiple convents around Poland and Ukraine, most prominent of which was one in Wadowice, Poland, where he was also elected prior. He installed a convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns in Przemyśl in 1884, and in Lvov in 1888.

From 1892 to 1907 Kalinowski worked to document the life and work of Theresa Marchocka, a 17th-century Discalced Carmelite nun, to assist with her beatification. He was a noted spiritual director of both Catholic and Russian Orthodox faithful.[39]

Kalinowski died in Wadowice of tuberculosis in 1907.[40] Fourteen years later, Karol Wojtyła, later known as Pope John Paul II, was born in the same town.

Remove ads

Veneration

Summarize

Perspective

Kalinowski's remains were originally kept in the convent's cemetery, but this caused difficulties because of the large number of pilgrims who came visiting. So many of them took handfuls of dirt from the grave that the nuns had to keep replacing the earth and plants at the cemetery. Kalinowski's remains was later translated to a tomb, but the pilgrims went there instead, often scratching with their hands at the plaster, just to have some relic to keep with them.[41] His remains were then moved to a chapel in Czerna, where they remain.[42]

Theologians approved Kalinowski's spiritual writings on 4 April 1943, and his cause was opened on 2 March 1952, granting him the title of Servant of God.[43] Pope John Paul II beatified Kalinowski in 1983 in Kraków, in front of a crowd of over two million people. On 17 November 1991, he was canonized when, in St. Peter's Basilica, Pope John Paul II declared his boyhood hero a saint.[44] Rafał was the first friar in the Order of the Discalced Carmelites to have been canonized since co-founder John of the Cross (1542–1591) became a saint in 1726.

Kalinowski's feast day is celebrated on 20 November (on 19 November in the Order of the Discalced Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel). He is considered a patron saint of soldiers and officers of Poland[45] and also of Polish exiles in Siberia.[46][47]

Remove ads

Literary works

- Carmelite Chronicles of the convents of Vilnius, Warsaw, Leopolis, and Kraków

- Translated the autobiography of Therese of Lisieux, The Story of a Soul into Polish

- Wrote biography of Augustine Mary of the Blessed Sacrament

- Kalinowski, Rafal, Czesc Matki Bozej w Karmelu Polskim, in Ksiega Pamiatkowa Marianska, Lwów-Warszawa 1905, vol. 1, part II, pp 403–421

- Kalinowski, J. Wspomnienia 1805-1887 (Memoirs 1805–1887), ed. R. Bender, Lublin 1965

- Kalinowski, Jozef, Listy (Letters), ed. Czeslaus Gil, vol. I, Lublin 1978, vol II, Kraków 1986-1987

- Kalinowski, Rafal, Swietymi badzcie. Konferencje i teksty ascetyczne, ed. Czeslaus Gil, Kraków 1987

See also

Notes

- His brother, Gabriel Kalinowski, was exiled to Shedrynsk for his role in the uprising. The brothers met in Perm and traveled together to Yekaterinburg at the beginning of the penal servitude (Bender 1977, p. 83). His brother, Karol Kalinowski, was also exiled (in February 1863) (Adamska 2003, p. 20).

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads