Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Sambal

Southeast Asian spicy relish or sauce From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sambal (Indonesian and Malay pronunciation: [ˈsambal]) is a category of chilli-based sauces or pastes originating in maritime Southeast Asia, particularly within the cuisines of Indonesia, Malaysia, Timor-Leste, Brunei, Singapore, southern Thailand and southern Philippines. Owing to historical connections and migration, sambal is also found in South Africa, Suriname and the Netherlands, while in Sri Lanka a local adaptation is known as sambol. In English, it is commonly described as an “Indonesian condiment”.[4][5][6][7][2][8]

Traditionally, sambal is prepared by grinding or pounding fresh or dried chillies with aromatics such as shallots, garlic, galangal and ginger, often combined with shrimp paste and seasoned with salt, sugar and acidic ingredients like lime juice or tamarind. Sambal may be served raw or cooked and can function as a condiment, a flavouring base or a standalone side dish.

The history of sambal is closely linked to the development of spice use in the region. Before the arrival of chilli peppers from the Americas in the 16th century, local communities prepared pungent relishes using indigenous and Old World ingredients such as long pepper, ginger, galangal and andaliman. Chilli peppers, introduced through Portuguese and Spanish trade networks, were rapidly adopted for their flavour, adaptability to tropical climates and compatibility with established cooking methods, soon replacing long pepper in most dishes. By the 18th century, chilli-based sambals were recorded across the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, with each community developing variations shaped by local ingredients and culinary traditions.

Today, sambal exists in a wide range of regional forms across Southeast Asia and in other parts of the world. While chilli remains the central ingredient, the addition of items such as fermented durian, torch ginger stems, coconut or sweet soy sauce produces distinctive variations linked to local ingredients and culinary traditions. Across Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, southern Thailand and Sri Lanka, numerous varieties of sambal have developed, reflecting both regional diversity and shared historical influences.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Indigenous and early hot spices of Southeast Asia

Before the introduction of chilli peppers (Capsicum spp.) from the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries, the peoples of maritime Southeast Asia prepared spicy relishes using indigenous and Old World pungent ingredients. Among the most prominent were long pepper (Piper retrofractum and Piper longum), ginger (Zingiber officinale), galangal (Alpinia galanga) and in certain regions, andaliman (Zanthoxylum acanthopodium), a local variety of Sichuan pepper.[9]

The exact emergence of sambal remains uncertain, as historical records do not provide clear evidence of its earliest development or geographic origin.[3] The widespread practice of giling, meaning the pounding, crushing or grinding of ingredients with a mortar and pestle, is shared across many Austronesian and Southeast Asian cultures. The word giling itself, meaning “to grind” or “to crush,” is derived from Proto-Austronesian roots referring to the action of rolling, turning or crushing.

In Java, cabay (Javanese long pepper, Piper retrofractum) was the principal hot spice, recorded in inscriptions and literature from at least the 10th century CE during the Mataram Kingdom.[10] Black pepper, introduced from India by the 12th century, expanded the repertoire of pungent flavours. In North Sumatra, the Batak people used andaliman as a defining seasoning in dishes such as arsik fish, often combined with ginger and torch ginger buds.[11] In Maluku and the Banda Islands, long pepper, ginger and galangal were blended with cloves and nutmeg in stews and preserved foods prior to the widespread adoption of chilli peppers.[12]

Across the Malay Peninsula, parts of Sumatra and coastal Borneo, historical Malay sources record the use of long pepper (lada panjang) with ginger, galangal and black pepper in spice pastes.[13] Tomé Pires, a Portuguese physician in Malacca between 1512 and 1514, noted that betel nut was chewed in the region for its warming properties.[14] Similar culinary traditions were recorded in mainland Southeast Asia, where long pepper featured in early Thai and Khmer curry pastes alongside ginger, galangal, lemongrass and wild pepper leaves (Piper sarmentosum).[15][16]

In the pre-Hispanic Philippines, ginger was the principal source of pungency in broths such as tinola, with long pepper (laya-laya) likely introduced via trade from the Indonesian islands.[17] In Vietnam and the former Champa territories, long pepper was known through maritime exchange and used mainly in medicinal preparations together with ginger and galangal.[15] Across the region, these spices were valued both for their flavour and for perceived health benefits, including aiding digestion and protecting against illness.[13]

Introduction of chili peppers to Southeast Asia

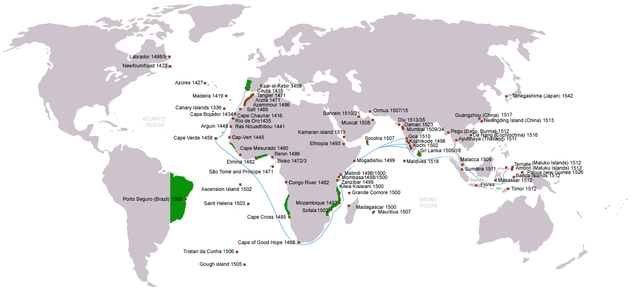

In the 16th century, chilli peppers, native to the Americas, were introduced to the Southeast Asian archipelago primarily through Portuguese and Spanish maritime trade routes.[18] The Portuguese, after their arrival in Goa, India, in 1498, brought chilli peppers to their colonies and trading posts, including Malacca in the Malay Peninsula in 1511, facilitating their spread throughout the Malay Archipelago.[19] Spanish traders likewise introduced chilli peppers to the Philippines by the mid-16th century.[20]

The capture of Malacca by the Portuguese under Afonso de Albuquerque in 1511 gave them control of a key maritime trading hub, enabling them to influence the spice trade and culinary practices across Southeast Asia.[21] The introduction of chilli peppers complemented, and in many cases supplanted, traditional spices, becoming a defining element in regional cooking from the 16th century onward.[19] Portuguese and Spanish traders connected key ports along maritime routes through India, Malacca, the Moluccas and coastal Java, enabling the diffusion of chilli peppers across Southeast Asia. Initially, they supplemented or replaced native spices such as long pepper, black pepper, ginger and galangal, becoming increasingly important in local cuisines. Their adaptability to tropical climates and compatibility with local tastes led to rapid adoption, gradually replacing long pepper in everyday cooking, although the latter remained in use in certain ceremonial and medicinal contexts.[13]

Chillies gained popularity for both economic and practical reasons. They allowed smaller amounts of costlier ingredients, such as meat or seafood, to be eaten with larger portions of rice, the region's staple food. Their strong flavour also helped mask the taste of less fresh or fermented foods common in the humid tropical climate. Despite an initial sensitivity to capsaicin, many Southeast Asian populations developed a cultural preference for the pungency of chillies, a taste reinforced by the pleasurable endorphin response associated with their consumption.[16]

By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, chillies had become fully integrated into the culinary landscape of the Southeast Asian archipelago. Fresh small chillies were commonly served whole or sliced alongside rice, noodles and side dishes.[20] In some cuisines, they were combined with other ingredients, for example ground peanuts in Thai som tam, while chilli-based sauces and pastes incorporated local seasonings such as shrimp paste, garlic, shallots, lime juice, palm sugar and soy sauce, creating complex, layered flavours. This widespread adoption of chilli peppers laid the foundation for the development of distinctive regional condiments, including the sambals of Indonesia and Malaysia, Thailand's nam prik and Vietnam's tương ớt tỏi (chilli–garlic sauce).[16]

Emergence of sambal

The introduction of chilli peppers into the archipelago quickly influenced existing spice-based condiments. Long before their arrival, communities across maritime Southeast Asia used stone mortars and pestles to pound long pepper, ginger, aromatic roots and other spices into coarse pastes. Chilli peppers were readily incorporated into these established methods alongside aromatics such as shallots, garlic, galangal and shrimp paste, creating the intense, layered flavours that came to characterise sambal and its many variants.[3][22]

Colonial-era accounts describe chilli-based condiments served with rice, fish and vegetable dishes.[22][3] By the 18th century, sambal had become a staple among diverse ethnic groups in the archipelago, including the Javanese, Minangkabau, Sundanese, Malay, Peranakans and Balinese, with numerous other communities developing their own local variations. These adaptations, shaped by available ingredients and cultural influences, laid the foundation for the wide variety of sambal found today.[22]

Beyond its role as a condiment, sambal was prepared in both raw and cooked forms, used as a side dish, flavouring base or cooking ingredient and adapted for everyday meals as well as festive occasions. Its versatility and compatibility with major dietary restrictions allowed it to cross cultural and religious boundaries, contributing to its status as a unifying element of Southeast Asian food culture.[21][23]

Remove ads

Culinary profile

Summarize

Perspective

Preparation and availability

Traditional sambals are freshly made using traditional tools, such as a stone pestle and mortar. Sambal can be served raw or cooked. There are two main categories of sambals, sambal masak (cooked) and sambal mentah (raw). Cooked sambal undergoes a cooking process resulting in a distinct flavour and aroma, while raw sambal is mixed with additional ingredients and usually consumed immediately. Sambal masak or cooked sambals are more prevalent in the western part of the Southeast Asian archipelago, including western Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, whereas sambal mentah or raw sambals are more common in eastern Indonesia.[24]

The chilli pepper, garlic, shallot and tomato are often freshly ground using a mortar, while the terasi or belacan (shrimp paste) is fried or burned first to kill its pungent smell and release its aroma. Sambal might be prepared in bulk, as it can be easily stored in a well-sealed glass jar in the refrigerator for a week to be served with meals as a condiment.[25] However, some households and restaurants insist on making freshly prepared sambal just a few moments prior to consuming to ensure its freshness and flavour; this is known as sambal dadak (lit. 'impromptu sambal' or 'freshly made sambal'). Nevertheless, in most warung and restaurants, most sambal is prepared daily in bulk and offered as a hot and

Today some brands of prepared, pre-packed, instant or ready-to-use sambal are available in warung, traditional markets, supermarkets and convenience stores. Most are bottled sambal, with a few brands available in plastic or aluminium sachet packaging. Compared to traditional sambals, bottled instant sambals often have a finer texture, more homogeneous content and thicker consistency, like tomato ketchup, due to the machine-driven manufacturing process. Traditionally made sambals ground in a pestle and mortar usually have a coarse texture and consistency. Several brands produce bottled sambals such as Heinz ABC sambal terasi[26] and several variants of sambal Indofood.[27][28] In the Netherlands a range of pre-packed sambals in glass or plastic jars is readily available from several brands (national and store brands) from almost all supermarkets and tokos.

Varieties of chili

The most common kinds of chili peppers used in sambal are:

- Cayenne pepper: a shiny, red and elongated pepper.

- Adyuma, also known as habanero: a very hot, yellow and block-shaped pepper.

- Madame Jeanette: a very hot, fruity yellow–light green, elongated, irregularly shaped pepper. Typical for Surinamese cuisine.

- Bird's eye chili: a very spicy, green–red, elongated pepper approximately 10 millimetres (0.39 in) wide and 50 mm (2.0 in) long.

Remove ads

Regional variations

Summarize

Perspective

Indonesia

In Indonesia, sambal is a ubiquitous condiment with significant regional diversity. Across the archipelago, there are reported to be between 212 and 300 distinct varieties, ranging in intensity from mild to extremely hot. Sambal is typically made by grinding or blending chilli peppers with various secondary ingredients such as garlic, shallots, tomatoes, shrimp paste (terasi) and lime juice. Preparation methods and flavour profiles vary according to local culinary traditions, available ingredients and cultural preferences.

Certain varieties are closely associated with specific regions or ethnic groups. Examples include sambal andaliman from the Batak people of North Sumatra, which incorporates Zanthoxylum acanthopodium (andaliman pepper);[29] sambal balado from the Minangkabau of West Sumatra, a sautéed chilli and tomato mixture often combined with eggs, eggplant or seafood;[30] and sambal matah from Bali, a raw sambal made with shallots, lemongrass and bird's eye chilli.[31]

Some sambals feature distinctive local ingredients, such as sambal durian (sambal tempoyak), which uses fermented durian and is found in Sumatra and parts of Kalimantan;[32] sambal bongkot from Bali, made with the stems of Etlingera elatior (torch ginger);[33] sambal gami from Bontang in East Kalimantan, cooked with various shellfish;[34] and sambal terung asam from Kalimantan, prepared with the sour Solanum ferox.[35]

Fruit-based sambals also occur, including sambal buah from Palembang, made with Mangifera kemanga (kemang mango) and pineapple; sambal belimbing wuluh with sour bilimbi;[36] and sambal pencit from Central Java, which incorporates shredded unripe mango.[25] Some recipes emphasise simplicity, such as sambal uyah-lombok, made only from raw chilli and salt, or sambal ulek, a plain raw chilli paste that can serve as a base for other preparations.

Regional sambals often accompany specific dishes or are integral to local foodways. For example, sambal colo-colo from Ambon is commonly paired with grilled fish, sambal luat from East Nusa Tenggara is served with se’i smoked meat,[37] and sambal pecak is a Betawi condiment for fried fish or chicken.[38] The Betawi version is more soupy and using ginger in the sambal.[39] Variants such as sambal tuktuk from the Batak incorporate andaliman and dried fish, while sambal taliwang from Lombok uses locally grown naga jolokia peppers.[40]

Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Thailand

In Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand and Singapore, sambal is a common accompaniment to rice and noodle dishes. While chilli and shrimp paste (belacan) form the base of many recipes, variations arise from differences in ingredient combinations, preparation methods and intended pairings.

One of the most well-known varieties is sambal belacan, made by pounding fresh chillies with toasted belacan in a stone mortar, seasoned with sugar and lime juice. Traditionally, limau kesturi (calamansi) is used, though regular lime is a common substitute outside Southeast Asia. Optional ingredients include tomatoes or sweet–sour fruits such as unripe mango. The sambal is eaten with raw vegetables or ulam, often as part of a rice meal. A Malaysian Chinese variation involves frying the belacan with chilli before serving.

Sambal jeruk is prepared from green or red chillies with kaffir lime, or with vinegar and sugar in place of lime and is typically served as a condiment with nasi goreng or noodle dishes. Sambal tempoyak, found in Pahang, Perak and parts of Brunei, incorporates fermented durian (tempoyak) and may be served raw or cooked. In the raw form, pounded chillies are mixed with dried anchovies and eaten with tempoyak; in the cooked version, the mixture is stir-fried with shallots, lemongrass, turmeric leaf, anchovies and sometimes petai or tapioca shoots. Sambal hitam Pahang is another regional variety that incorporates belimbing to add a sour note.

Other varieties include sambal kicap, a blend of sweet soy sauce, shallots, garlic and bird's eye chilli used as a dipping sauce for fried foods or as a condiment for soups; Sambal tumis, a stir-fried sambal made from dried and fresh chillies, belacan and gula Melaka, is a traditional accompaniment to nasi lemak, typically served with fried anchovies, peanuts, cucumber and boiled egg.[41]

The Philippines

In the southern Philippines, particularly among the Tausug and other Moro communities of the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao, sambal refers to a spicy condiment or appetiser distinct from, but related to, the chilli-based sambals of neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia. It is commonly served as a starter, accompanied by sliced cucumber, chopped radish or green mango and is intended to stimulate the appetite before the main meal.[42] Typical ingredients include shallots, ginger, onions, chillies, peppercorns and other aromatics, which are pounded or blended to produce a piquant mixture.[42][43] In the Philippines, the term is also used for a sweet and spicy broth, known as sambal soup, served with satti, a breakfast dish of skewered grilled meat and rice balls.[44]

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, sambol is believed to have been introduced during the colonial era, derived from the chilli-based sambal of the Dutch East Indies. The term is said to have acquired its distinctive “o” when adopted into local usage.[45] Once introduced, the preparation was adapted to incorporate locally abundant ingredients such as chillies, grated coconut, lime juice and vegetables like nelum ala (lotus stem) and dambala (winged bean). Traditionally, the ingredients are combined using a wooden grinding device called a mirisgala, producing a spicy side dish that is typically consumed uncooked.

Sri Lankan sambols differ from those of Southeast Asia in that they are generally prepared from fresh, uncooked ingredients. Commonly, fresh chillies, shallots, coconut and garlic are ground with a mortar and pestle, then mixed with a souring agent such as lime or lemon juice. The result resembles condiments such as Mexican salsa or Laotian jaew. Variations are often served as accompaniments to rice, bread or other staple foods.

A notable type is seeni sambol (also spelled sini sambol or seeni sambal), a hot–sweet preparation made from onions, crumbled Maldives fish and spices. Its name derives from the Sinhala word for “sugar.” Pol sambol (thengkai sambal in Tamil) is made from scraped coconut, onion, green and red chillies and lime juice, sometimes with the addition of Maldives fish or tomato in place of lime.

Lunumiris, literally “salt chilli,” is a paste of red chilli and sea salt, often enriched into katta sambal with onions, Maldives fish and lime juice. Other varieties include vaalai kai sambal, made from boiled and mashed unripe plantain, scraped coconut, chopped green chillies, onion, salt and lime juice. Among Jaffna Tamils, a preparation called campal is produced, bearing similarities to a chutney.

The Netherlands

Sambal is a common spicy condiment in Dutch cuisine, introduced from Indonesia, a former Dutch colony. It is widely available in supermarkets and Asian specialty stores (tokos), with popular brands including Conimex and Koningsvogel. Common varieties sold in the Netherlands include sambal oelek, a simple chili paste and sambal badjak, a sweet, cooked sambal often prepared with onions.[46][47]

In the Netherlands, sambal is used as a condiment for Dutch-Indonesian fusion dishes such as rijsttafel, nasi, bami and is also added to snacks and sandwiches. Among the available types, sambal oelek remains the most popular, though other ready-to-use jarred variants are also common.

South Africa

Sambal is a known condiment in South Africa, particularly within Cape Malay cuisine, which reflects the influence of Indonesian and Malaysian ancestors brought to the region during the colonial era.[48] South African sambals are typically chili-based and often include ingredients such as chilies, garlic and shallots, sometimes combined with local flavorings. They are used to add spice and zest to dishes and have been adapted to local tastes, with variations including cucumber sambal. Through historical migration and cultural blending, sambal has become an integrated element of South African cuisine while retaining its characteristic chili-based profile.[49]

Suriname

Sambal is a commonly used condiment in Surinamese cuisine, particularly among the Javanese-Surinamese community, who brought their culinary traditions during the colonial era. It is typically served with rice, meats and tempeh, varieties include sambal prepared with chicken hearts, gizzards or liver, as well as tempeh sambal, often spiced with the locally grown Madam Jeanette chili pepper for added heat.[50] Distinctive Surinamese versions incorporate local ingredients, such as Surinam cherry sambal and peanut sambal (pinda sambal), which blend indigenous produce with Indonesia-inspired preparation methods.[51][52] Sambal in Suriname is commonly made at home for freshness but is also widely available in markets and restaurants.

Remove ads

Sambal as an ingredient in dishes

Summarize

Perspective

Beyond its role as a condiment, sambal is frequently used as a cooking ingredient, forming the base of many dishes that incorporate large amounts of chilli peppers. In Indonesia, preparations beginning with the term sambal goreng (“fried sambal”) refer to stir-fried sambal combined with a main ingredient. Common examples include potatoes (sambal goreng kentang), liver (sambal goreng hati), beef or buffalo skin crackers (sambal goreng krecek), anchovies (sambal goreng teri) and tempeh (sambal goreng kering tempe).

In Minangkabau cuisine, dishes prefixed with balado, meaning “with chilli pepper,” similarly indicate the incorporation of sambal into the recipe, as in udang balado (prawns with sambal). Sambal is also served alongside fresh vegetables, as in the Sundanese sambal lalab, or paired with seafood such as squid or cuttlefish (sambal cumi or sambal sotong), dried prawns (sambal udang kering) and eel (sambal belut). Other variations include mushroom-based sambal jamur, fish preparations like sambal ikan, which may be cooked into a moist curry-like form or reduced to dry floss (serunding ikan) and the Javanese sambal wader, made from yellow rasbora and sambal terasi, believed to have been served since the Majapahit era.[53]

In Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, sambal features in popular dishes such as grilled stingray (Pari bakar), where barbecued stingray is served with sambal paste and serunding daging, a slow-cooked beef sambal with a floss-like texture. Ayam masak sambal is often served at kenduri kahwin (wedding feasts), highlighting its place in celebratory meals.[54]

Remove ads

See also

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sambal.

- Balado, Minang-style sambal goreng

- Hot sauce, also known as chili sauce or pepper sauce

- Nam phrik, the Thai equivalent of sambal

- Salsa (sauce)

- Indonesian cuisine

- Malaysian cuisine

- Singaporean cuisine

- Peranakan cuisine

- Filipino cuisine

- Varieties of sambal

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads