Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

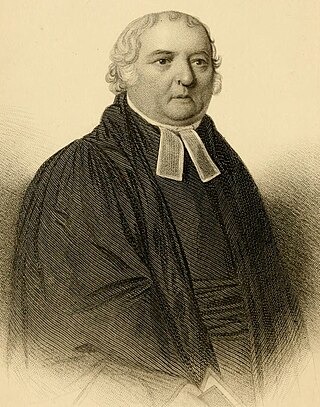

Samuel Marsden

Church of England chaplain, missionary, agriculturalist, magistrate (1765–1838) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Samuel Marsden (25 June 1765 – 12 May 1838) was an English-born priest of the Church of England in Australia and a prominent member of the Church Missionary Society. He played a leading role in cross-cultural interchange with Māori people and bringing Christianity to New Zealand. Marsden was a prominent figure in early New South Wales, partly through his role as the colony's senior Anglican cleric and as a pioneer of the Australian wool industry. He is also remembered for his harsh punishments meted out as a magistrate at Parramatta, his bigoted social views and his self-serving financial dealings, all of which attracted contemporary criticism.[2][3]

Remove ads

Early life

Born in Farsley, near Pudsey, Yorkshire in England as the son of a Wesleyan blacksmith turned farmer, Marsden attended the village school and spent some years assisting his father on the farm. In his early twenties his reputation as a lay preacher drew the attention of the evangelical Elland Society, which sought to train poor men for the ministry of the Church of England. With a scholarship from the Elland Society Marsden attended Hull Grammar School, where he became associated with Joseph Milner and the reformist William Wilberforce, and after two years, he matriculated, at the age of 25, at Magdalene College, Cambridge.[4] He abandoned his degree studies to respond to the call of the evangelical leader Charles Simeon for service in overseas missions. Marsden was offered the position of second chaplain to the Reverend Richard Johnson's ministry to the Colony of New South Wales on 1 January 1793.

Marsden married Elizabeth Fristan at Holy Trinity, Hull on 21 April 1793. The following month William Buller, the Bishop of Exeter, ordained him as a priest.[5]

Remove ads

New South Wales

Summarize

Perspective

Rapid rise in power and wealth

Marsden travelled as a passenger on the convict ship, William to New South Wales, his first child Anne being born en route. He arrived in the colony on 10 March 1794, and the Lieutenant-Governor, Francis Grose gave him the position of assistant chaplain at Parramatta, 15 miles (24 km) inland from the main Port Jackson settlement. Marsden was advised to be "submissive and corteous" to the military government of the New South Wales Corps, and was quickly rewarded by Grose with a 100-acre land grant at Marsfield, supplemented with free convict labourers.[6]

However, Marsden took issue with the extortion and the alcohol-driven economy of the officers, and in 1795 sided with the newly appointed Governor John Hunter to attempt to reform the system. In return, Hunter gave Marsden significant political and social power by naming him as the magistrate for Parramatta and also giving him a further land grant of 374 acres.[6]

Marsden, receiving dual salaries as both a chaplain and magistrate as well as deriving an income from the produce of his landholdings, further built upon his wealth in 1797 by purchasing some of the first flock of valuable merino sheep imported into the colony. He also established a business partnership with the merchant Robert Campbell, one of the most prominent export traders operating in Sydney.[6]

By 1802, Marsden owned six properties totalling 619 acres, including several houses and twelve convict servants. He had succeeded Richard Johnson as the senior Church of England chaplain in New South Wales and retained his position as magistrate at Parramatta, making him one of the wealthiest and most influential identities in the colony. By 1806 his landholdings rose to 3,000 acres (12 km2), which started criticisms against Marsden for his financial self-interest taking precedence over his religious role.[7][6]

The "Flogging Parson"

In the early 1800s, there was a large increase in the proportion of Irish Catholic convicts being sent to New South Wales. Marsden was a staunch Anglican and Tory with an "inveterate hostility" toward Catholics and the Irish.[6] In his role as magistrate, he became known as the "Flogging Parson",[8] with the historical record showing he handed down severe punishments (notably extended floggings), even by the standards of his day on the accused. The Australian historian, Robert Hughes in his book, The Fatal Shore, describes Marsden as, "a grasping Evangelical missionary with heavy shoulders and the face of a petulant ox." Hughes declares that Marsden's "hatred for the Irish Catholic convicts knew no bounds".[9]

In 1800, ten Irish prisoners were interrogated and tortured after rumours surfaced of an Irish plot for insurrection in New South Wales. Marsden was one of several magistrates who ordered 100 to 500 lashes to be given as a means to extort information. Marsden himself described his interrogation of Paddy Galvin to Governor Philip Gidley King:

"Mr Atkins and I ordered him to be punished very severely in hopes of making him inform...punished on his back and also his bottom when he could receive no more on his back. Galvin was just in the same mood when taken to the Hospital as when he was tied up... I am sure he will die before he will reveal anything"[6]

Joseph Holt, who was transported to Sydney for his role in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, also gave a vivid account in his memoirs of the interrogation of Irish convicts. He related:

"I have witnessed many horrible scenes; but this was the most appalling sight I had ever seen...the blood, skin, and flesh blew in my face" as floggers "shook it off from their cats" [referring to the cat-of-nine-tails scourging lash]...The next prisoner who was tied up was Paddy Galvin, a young lad about twenty years of age; he was also sentenced to receive three hundred lashes. The first hundred were given on his shoulders, and he was cut to the bone between the shoulder-blades, which were both bare. The doctor then directed the next hundred to be inflicted lower down, which reduced his flesh to such a jelly that the doctor ordered him to have the remaining hundred on the calves of his legs"[10]

Marsden's attitudes to Irish Roman Catholic convicts were illustrated in a memorandum which he sent to his church superiors during his time at Parramatta:

"The number of Catholic Convicts is very great... and these in general composed of the lowest class of the Irish nation; who are the most wild, ignorant and savage Race that were ever favoured with the light of Civilization...Their minds being Destitute of every Principle of Religion & Morality render them capable of perpetrating the most nefarious Acts in cool Blood...No Confidence whatever can be placed in them"[11]

Despite Marsden's opposition to Catholicism being practised in Australia, Governor King permitted monthly Catholic masses in Sydney from May 1803 under police surveillance.[12] When the Irish convicts actually organised a brief rebellion in 1804 at Castle Hill, Marsden fled Parramatta with the loyalist women and children to the safer location of Sydney until the uprising was over.[6]

Involvement in the orphanage and the Female Factory

Marsden was an active leader in the creation of the first orphanage for girls in the colony, which opened in 1801.[6] His altruism, however, was tempered by a strong dislike of any criticism of the institution. When a member of the public voiced an opinion that one of orphans was of scandalous reputation, Marsden sentenced that person to 100 lashes.[13]

Marsden was also the originator of the New South Wales Female Register which classed all women in the colony as either "married" or "concubine". Only marriages within the Church of England were recognised as legitimate on this list; women who married in Roman Catholic or Jewish ceremonies were automatically classed as concubines.[9]

Related to this was Marsden's involvement in the establishment in 1804 of the Parramatta Female Factory which was a labour camp facility for female convicts who were not otherwise suitably employed or married. The inmates at the Factory, which was a dirty enclosed loft above the jail, were forced to spin the coarse wool, which was sold to the government by landholders such as Marsden, into yarn to make the convict clothing. The conditions for the women were awful and prostitution of the inmates was rife. Marsden complained of the conditions but praised both the cost-savings to the government and that the work was keeping the women from "idleness and dissipation".[6][9]

Marsden was the main proponent for the construction of a new building for the Female Factory, which was completed in 1821. However, conditions for the women were worsened after the move. The superintendent of the Factory was paid based on the clothing produced by the women, so they were worked as hard as possible. Meagre rations, overcrowding and poor sanitation led to some dying of disease and hunger, while their infant children were removed and taken to the orphanage. Discipline was severe and punishments included having their heads shaved and working a treadwheel. Marsden viewed the treatment of these female convicts in the new building with satisfaction, praising "such order and discipline".[14]

Visit to England and planning for a New Zealand mission

In 1807 he returned to England to report on the state of the colony to the government, and to solicit further assistance of clergy and schoolmasters. He promoted the need for secular and religious educators to be sent to New South Wales and encouraged his associates to donate quality books so that he could establish a public library. He also organised the purchase of premium sheep and Suffolk cattle to add to his herds in the colony.[6]

While in England, he met the young Maori chief Ruatara, who had gone to Britain from New Zealand in the whaling ship Santa Anna and been stranded there.[15] Marsden had previously met Ruatara and his uncle Te Pahi in Sydney where he had been impressed by the mannerisms of the Maori men and their willingness accept Anglican religious instruction.[16] Marsden and Ruatara returned to New South Wales together on the convict transport Ann,[15] where Marsden discussed establishing a Christian mission at Ruatara's homeland at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands of New Zealand.[17] They arrived in Sydney in February 1810 and Ruatara, who was accepting of the plan for the mission at Rangihoua, later travelled with Marsden on his voyage to establish the mission in 1814.[15]

Views and interactions with Aboriginal Australians

Only months after his arrival at Parramatta in 1794, Marsden acquired an Indigenous Australian boy aged around three years old. The boy's mother had been shot by the whites and Marsden wrote that the child had been taken from the dead mother's breast. Marsden named the boy Tristan Maumby and he was brought up in the Marsden household, attending school and trained in the ways of a house servant. At the age of 16, Tristan accompanied the Marsden family on a voyage to England. While the vessel was anchored at Rio de Janeiro, Marsden beat Tristan for drinking alcohol. Tristan subsequently robbed Marsden of a considerable sum of money and absconded into the streets of Rio. Marsden made no attempt to find Tristan and proceeded with his journey to England.[18]

During the late 1790s and early 1800s, the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars between the colonists and the local Aboriginal people were at their height. As a magistrate, Marsden was central in organising operations against the Aborigines. He regularly used the ruthless tactics of interrogation, hostage taking and forcing young tribesmen to guide soldiers to capture or kill the supposed leaders of the Aboriginal resistance. By these methods Marsden was able to capture notable figures such as Tedbury and Musquito, and kill others such as Talloon. During the conflict, he also obtained another Aboriginal child whose mother was axed to death. Marsden named the boy John Rickaby but he died soon after. While trying to arrange a punitive expedition against "the natives", Marsden was quoted as saying "there never would be any good done until there was clear riddance of them", and that "the Aborigines are the most degraded of the human race".[19][20][21]

This attitude to the original inhabitants continued throughout his life. During the 1820s, as the British pushed into the interior of the continent, Marsden received large land grants on the country of the Wiradjuri people. His economic interests far outweighed any concern for the Wiradjuri in the subsequent Bathurst War, with his stock-keepers participating in the conflict which resulted in the Indigenous people being forced off the land.[22]

When a proposal for a 10,000 acre reserve to provide for the displaced Wiradjuri was raised, Marsden objected as he thought it would interfere with the colonists' ability to access land. He again dismissed the Aborigines as "degraded and idle" who would be "submerged and destroyed" by superior Europeans. Marsden also actively sabotaged another Aboriginal reserve run by the evangelist Lancelot Threlkeld for the Awabakal people of Lake Macquarie. Marsden refused to provide funding for the mission, despite Threlkeld making pioneering inroads into the study of Awabakal language.[6]

Business and politics

In 1811, Marsden was the first colonist to export wool to England from Australia for commercial use. His shipment of 5,000 lbs (2267 kg) of wool was sold in England for £1250. Marsden was an important promoter of the wool staple, even though his contribution to technology, breeding and marketing was far eclipsed by that of the famous colonist John Macarthur.[6]

Marsden's fortunes in colonial administration at this time though were less agreeable. He raised the ire of Governor Lachlan Macquarie by refusing to work with ex-convicts (known as emancipists) in government appointed positions. His socially conservative outlook maintained that working with such people was "a degradation to his office". Marsden's antipathy for Macquarie's reformist ideals later led to consequential disputes between him and the governor, and for a brief period, he lost his magistracy.[6][23]

Despite Macquarie granting Marsden more packages of land and providing funds for the renovation of Marsden's churches including St John's Church in Parramatta, Marsden continued actively to undermine Macquarie's authority. When John Bigge arrived in the colony in 1818 to conduct an enquiry, Marsden sent constant communication to him and other colonial directors discrediting Macquarie, which ultimately contributed to Macquarie resigning from the governorship.[23]

With Macquarie's departure, the colony shifted more toward a plantation economy, where large landholders like Marsden benefited by being provided with priority access to further land allocations and cheap convict labour. Together with other wealthy colonists, Marsden helped form the Agricultural Society, which lobbied for further reactionary policies such as abolishing duties and taxes and reducing convict labourers to serfdom. By 1828, Marsden had increased his wealth, owning around 5,000 acres of land, worked by 80 convict servants.[6][23]

Recommended for dismissal

Marsden continued his reputation for cruel discipline throughout his career. In the 1820s, Marsden endorsed the scheme brought in by the colonial authorities to increase the maximum corporal punishment of flagellation to 500 lashes. He was consistently criticised for ordering floggings before suspects were tried or sentenced and in the proceedings of convict William Refraine, Marsden ordered him to be flogged despite a court exonerating him of guilt. In another case, Marsden had a female witness, Ann Rumsby, arrested and jailed for several years because he didn't agree with her statement.[6]

In 1825, after a series of questions were raised about the standards of punishment of Marsden and his fellow magistrates, an enquiry was held. It was found that Marsden was a consistent culprit in the practice of torturing suspects by flogging while interrogating them in order to obtain information or confessions. As a result of this enquiry, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Bathurst, stated that Marsden was "untrustworthy" and "turbulent", and should not be placed in any position of authority. Marsden also lost the confidence of his long-time patron William Wilberforce, who called him "corrupt" and a "liar", while another colonial authority John Bigge said that Marsden was "stamped with severity".[6]

Marsden consequently lost many of his government appointments, but it was the recommendation by the Archdeacon of New South Wales, Thomas Hobbes Scott, that Marsden be dismissed from the church which would have had the most significant ramification for him. In the end Scott's recommendation was overruled and Marsden retained his clerical post. When Governor Darling, a man remembered for his cruelty, arrived to take command of the colony in 1826, Marsden was restored to most of his government positions.[6]

Remove ads

Mission to New Zealand

Summarize

Perspective

Background

In contrast to his treatment of Aboriginal Australians, Marsden befriended many Māori visitors from New Zealand. He provided them with accommodation, food, drink, work and an education at Parramatta. Marsden learnt the Māori language and made an English-Māori translation sheet of common words and expressions. He was of the view that the Māori would be readily converted to Christianity and actively pursued a vision to form a Christian mission in New Zealand.[24]

Marsden was a member of both the London Missionary Society (LMS) and the Church Missionary Society (CMS). He became head of operations in the South Pacific for the LMS after he housed and found employment for the society's missionaries like Rowland Hassall who were forced out of Tahiti. However, it was through the CMS that Marsden was able to become the director in the establishment of the New Zealand mission.[6]

Marsden was greatly concerned about European whalers, sealers and sandalwood traders massacring and corrupting Pacific Islander and Māori people, and in 1813 he successfully lobbied the CMS to form a New South Wales chapter with him as the president in charge of placing a mission in New Zealand.[25][26] Marsden also formed the short-lived "Philanthropic Society" to fund the mission, but ultimately it was his own resources and £500 per annum from the CMS that initially financed the scheme.[27]

Preliminary excursion to New Zealand

CMS missionary Thomas Kendall, along with mariner Peter Dillon and tradesmen William Hall and John King, were chosen by Marsden to lead an investigative journey to the Bay of Islands.[28] In March 1814,[29] they proceeded from Sydney on board Marsden's brig Active, which he had purchased for £1,400.[30][1] Once arrived, Kendall established contact with Marsden's Maori friend Ruatara, as well as two other significant rangatira (chiefs) from the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe), who controlled the region around the Bay of Islands, including noted war leaders, Korokoro and Hongi Hika, who had helped pioneer the introduction of the musket to Māori warfare in the previous decade. The three chiefs agreed to the proposal of the Christian mission and returned to Sydney with Kendall on 22 August.[31]

Establishment of the mission at Rangihoua

As a result of the successful initial investigatory voyage, Marsden quickly organised a second journey with himself as leader, to establish the mission settlement. The Active departed from Sydney on 14 November 1814,[32] with Marsden, Kendall, King and Hall, together with other settlers, their supplies and several of Marsden's horses. Also on board were the three Maori chiefs who had been given military uniforms to wear, which Marsden surmised would assist him to wield influence at the Bay of Islands. He also offered to pay the Maori crewmen on the Active equal rates to white men, the extra cost being covered by the CMS. Interestingly, before leaving Sydney, Ruatara was informed that the mission was just a front for British colonisation which would lead to the Maori being displaced and degraded just like the Aboriginal Australians.[6]

The expedition arrived at Ruatara's dominion of Rangihoua Bay on 24 December 1814. The following day, which happened to be Christmas, Marsden raised the Union Jack over Oihi Bay (a small cove in the north-east of Rangihoua Bay) and gave the first known Christian sermon on New Zealand soil.[33][34] The service from the Church of England Book of Common Prayer was read in English but it is likely that, having learnt the language from Ruatara, Marsden preached his sermon in the Māori language.[35] Ruatara was prevailed upon to explain those parts of the sermon the 400-strong Māori congregation did not understand.

Marsden later visited the neighbouring tribal areas, including the Okuratope Pā in Hongi Hika's territory. He also secured a cargo of timber to sell in Sydney. Marsden, who believed in the principle of "commerce before conversion", reckoned that trade brought back on the Active would earn around £1,000 per year.[6] On 24 February 1815, Marsden exchanged 12 axes with Ruatara to gain exclusive access to 200 acres of land at Rangihoua for the first Christian mission in New Zealand.[33] Ruatara, who was ill and died several weeks later, was told to make sure his people understood that this package of land was for white people only. Marsden left 25 Europeans at Rangihoua to build the mission under the management of Kendall, and to reduce the likelihood of the local people attacking this group, Marsden took ten Maori with him back to Sydney as surety.[6]

One of these hostages was the Ngāpuhi chief Tītore, who spent two years with Marsden at Parramatta,[36] before sailing to England in the Kangaroo[37] where he visited Professor Samuel Lee at Cambridge University and assisted him in the 1820 publication of First Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language.[38]

Weapons trade and the Musket Wars

Almost immediately, the fledging settlement at Rangihoua struggled to survive as the whites there had little that the Maori leaders wanted, except guns. Marsden had already given Hongi Hika a musket on his first trip to New Zealand, and the Europeans remaining at mission site found themselves having to compete with visiting whalers and merchants to provide weapons and ammunition in order to trade with the Maori for food and resources such as flax and timber.[6]

Marsden had experience of trading illicit items for profit at missionary sites under his direction. At Tahiti, his LMS missionaries traded rum and cheap firearms to the ruling warlord Pōmare II in return for pigs which were sold in Sydney for considerable profit. In 1816, Marsden's vessel, the Active, even carried several cannons to Tahiti which were traded for 126 hogs.[6]

Word of these activities reached Sydney in 1817, where the The Sydney Gazette published an article aimed at Marsden ridiculing his overt hypocrisy in providing weapons and alcohol for his own profit to people whose souls he was meant to be saving. The article also raised issues around his poor treatment of Aboriginal Australians and his hoarding the books that were donated to him for the establishment a public library.[39] Marsden countered by suing the Gazette and making a statement that weapons trade at the mission sites was forbidden.[6]

This statement proved hollow, as Marsden's appointees at Rangihoua continued to trade guns to the Maori, with Thomas Kendall and William Hall becoming large-scale arms dealers. Hongi Hika was the main local beneficiary of the weapons provided by the missionaries as well as the whalers, and was able to implement devastation on neighbouring tribes during part of what has become known as the Musket Wars. In 1818, for instance, his militia raided the people of East Cape, returning with 2,000 prisoners and the severed heads of 70 victims. These heads were likely to have been later traded to the British as toi moko (preserved heads) for more guns, due to their value as collectable curiosities in the colonial market.[6][40][41]

Marsden did not make another visit to check on the operations at Rangihoua until 1819. Despite witnessing first-hand the effects of the gun trade, he still kept Kendall and Hall employed as missionaries. Marsden did however place a new chaplain, John Gare Butler, in charge of the mission. On this visit, Marsden traded 48 axes with Hongi Hika for 13,000 acres of land at Kerikeri for a new mission site. In a baffling move, Marsden also offered Hongi Hika a shotgun if he would cease buying guns from Kendall.[6]

Marsden returned again in 1820 on board HMS Coromandel, for the contractual purpose of procuring a cargo of timber in the Firth of Thames for the Royal Navy. He found the trade in guns and heads was flourishing despite his appointment of Butler, and further witnessed the destructive effects on Maori society. There was also minimal interest of the local people being converted to Christianity, with the few who attended Marsden's sermons falling asleep. In an implicit acceptance of the gun trade, Marsden still kept Butler and Kendall employed at the mission, stating that "New Zealand must suffer before becoming a civilized nation".[6][42]

Meanwhile, Hongi Hika travelled with Kendall to England on the whaling ship New Zealander.[43] where he met King George IV, who gifted him a suit of armour. They also obtained further muskets when passing through Sydney on the return to New Zealand. Kendall's continued weapons trade, opposed in words but not actions by Marsden, was an important means of support for the new Kerikeri mission station. [44][45]

Managing issues associated with the mission

Marsden came under pressure from within the Church Missionary Society to do something about the scandalous operations occuring at the mission. In addition to the weapons trade, news arrived that Thomas Kendall had abandoned his wife for the daughter of a Māori tohunga (priest), and had also flirted with Maori traditional religion. The CMS also tried to establish a committee to investigate financial irregularities at the mission, but Marsden quickly had it dissolved. Furthermore, his appointee, John Butler, had written to Governor Macquarie outlining Marsden's hypocritical attitude to the gun trade.[6]

Adding to Marsden's troubles were the thirteen deaths of Maori children who had previously been taken as hostages to New South Wales to be educated at Marsden's purpose-built Parramatta Maori Seminary. One of the dead boys was Te Ahora, a son of Te Koki, chief at Kawakawa. These deaths forced Marsden to shut the seminary.[46][47]

The CMS subsequently sacked Kendall in 1822 and Marsden sailed to New Zealand the following year to remove both him and Butler from their positions. On the return voyage, they survived after their ship the Brampton was wrecked.[48] Marsden later went to some trouble talking to all Australian printers to prevent Kendall from publishing a Māori grammar book, apparently largely out of spite.[citation needed] Marsden appointed Henry Williams as the new leader of the mission who concentrated on religious instruction instead of trafficking guns.[6]

Later involvement in the mission

Marsden visited the New Zealand mission in 1827 and again in 1830 where he oversaw peace negotiations between rival iwi during the Girls' War.[6]

Marsden's final journey to the mission in 1837, like some previous trips, was made in response to controversy. Reverend William Yate, appointed as a missionary to New Zealand in 1826, had become embroiled in a major sex scandal involving oral sex and mutual masturbation with dozens of boys and young adult males at the mission and elsewhere. Damning testimonies of homosexual paedophilia from children at the mission forced the Anglican Archbishop of Sydney, William Broughton, to dismiss Yate. Marsden, who was infuriated with Yate's activities, made the journey to New Zealand after Yate had been banished, to check on its residents. Yate was never punished but the scandal seems to have had a toll on the ageing Marsden who died the following year.[49][50][51]

The mission would struggle on in competition with nearby Wesleyan and Catholic missions. In the 1820s, Kerikeri became the main mission in New Zealand (where the mission house and stone store can still be seen). Ultimately a model farming village was built at Te Waimate. By the 1830s[52] the houses of the mission at the old Rangihoua site had deteriorated and some buildings were moved to Te Puna, further to the west in Rangihoua Bay.[33][53] The mission finally closed in the 1850s.[54]

Remove ads

Death

Marsden was on a visit to the Reverend Henry Stiles at St Matthew's Church at Windsor, New South Wales when he succumbed to an incipient chill and died at the rectory on 12 May 1838.[55]

Marsden is buried in the cemetery near his old church at Parramatta, St John's.[56]

During his life, Marsden had amassed 29 farms and properties amounting to 11,724 acres, which included several mansions and homesteads. His overall worth upon his death was £30,000, equivalent to a multi-millionaire in today's currency.[6]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

The Sydney suburb of Marsden Park, located near to where Marsden had his 1,400 acre Mamre property, is named after him.[57] Marsden Point in New Zealand was also named in his honour.

Marsden Street, Parramatta, is named after him.[58]

Samuel Marsden Collegiate School in Karori, Wellington was named after Marsden. Houses at King's College, Auckland, King's School, Auckland and at Corran School for Girls are also named after him.

The Marsden Cross, erected near Rangihoua Bay in 1907, marks the place where Marsden delivered the first sermon on New Zealand soil.[59]

Rangihou Reserve in Parramatta is named after the mission site in New Zealand, and is where Marsden established his short-lived Parramatta Maori Seminary.[47]

Marsden introduced winegrowing to New Zealand with the planting of over 100 different varieties of vine in Kerikeri, Northland. He wrote:

New Zealand promises to be very favourable to the vine as far as I can judge at present of the nature of the soil and climate[60]

There are approximately 135 sermons written by Marsden in various collections around the world. The largest collection is in the Moore Theological College Library in Sydney, Australia. These sermons reveal Marsden's attitudes to some of the controversial issues he faced, including magistrates, the Aboriginal people and wealth. A transcription of the Moore College collection can be found online.[61][62]

Remove ads

Family

Marsden and his wife, Elizabeth Fristan, had several surviving daughters and a son. Two other sons died in infancy, one from an incident involving a wheelbarrow, and the other was scalded to death in a kitchen accident. His wife also suffered a hemiplegic stroke during childbirth in 1811 and was partially paralysed for the rest of her life.[6]

One of his daughters, Ann, married the Anglican priest Thomas Hassall. A grandson, also named Samuel Marsden, became the first Anglican Bishop of Bathurst.[63]

Remove ads

In fiction and popular culture

The Australian poet Kenneth Slessor wrote a satirical poem criticising the parson, "Vesper-Song of the Reverend Samuel Marsden".[64]

New Zealand reggae band 1814 took their name from the year that Marsden held the first sermon in the Bay of Islands.[65]

Bryan Bruce's 2001 documentary, Workhorse to Dreamhorse includes a story about Marsden's stallion.[66]

A portrait of Marsden based on Robert Hughes' The Fatal Shore appears in Patrick O'Brian's book The Nutmeg of Consolation.[citation needed]

In the 1978 Australian television series Against the Wind, Marsden was portrayed by David Ravenswood.[citation needed]

In the 1980 television adaptation of Eleanor Dark's 1941 novel The Timeless Land, Marsden is portrayed by John Cousins.[citation needed]

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads