Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

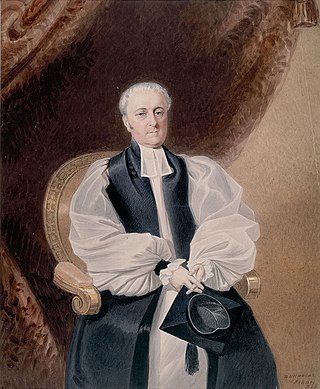

William Grant Broughton

Australian bishop (1788–1853) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

William Grant Broughton (22 May 1788 – 20 February 1853) was a British-born Anglican clergyman who served as the first and only Bishop of Australia. Broughton was born in London and began his career as a clerk at the East India Company, before graduating from Cambridge University and being ordained as a priest in 1818. He was appointed Archdeacon of the Colony of New South Wales and arrived in Australia in 1829. Upon the establishment of the Diocese of Australia in 1836, he was installed as the first Bishop of Australia.

Broughton is known for his opposition to the education reforms proposed by Governor of New South Wales Richard Bourke in 1831, modelled on the Irish National schools system. Broughton opposed moves towards religious equality and state-supported schooling, suspicious of the growing recognition and presence of the Catholic and Presbyterian churches in Australia. He believed that the Church of England should continue to enjoy special privileges as a semi-official religion within the colony. He established a number of Anglican educational institutions, including The King's School, Parramatta, and helped to expand the church's presence after the passage of the Church Act of 1836 by dedicating new church buildings, supporting the establishment of new Dioceses in Oceania, and recruiting a substantial pool of new clergy.

Broughton was a committed high churchman who opposed liberalism and the growing movement towards Catholic emancipation. He served on the New South Wales Executive Council and Legislative Council, where he played a significant role in the economic management of the colony. He was known for his conservatism and for his defence of the Church of England's special status within the growing colony.

Remove ads

Early life and education

William Grant Broughton was born on 22 May 1788 in Westminster, London.[1] His family was not wealthy, but did have influential connections, including with Lord Robert Cecil, Marquess of Salisbury, and the Cecil family.[2][3] He attended Barnet Grammar School between 1794 and 1796 and graduated from The King's School, Canterbury in 1803. He was awarded an exhibition to Cambridge University, but after the death of his father left him unable to afford to attend, he instead became a clerk for the East India Company.[1][4] In 1814 he inherited a sum of money from an uncle and was able to enrol at Pembroke College, Cambridge, from which he obtained a Bachelor of Arts in 1818 followed by a Master of Arts in 1823.[1][4] He graduated as sixth wrangler—the sixth-highest scoring student—after undertaking the Mathematical Tripos.[5]

Remove ads

Early ministry and views

Summarize

Perspective

In 1818 Broughton was ordained as a deacon by Thomas Burgess, Bishop of Salisbury, and later that year was ordained to the priesthood by George Pretyman Tomline, Bishop of Winchester.[1][6] On 13 July 1818 he married Sarah Francis, with whom he would go on to have three children—daughters Emily and Phoebe, and a son who died soon after his birth.[1] Upon his ordination, he was appointed curate to John Keate, the rector of Hartley Wespall and the Headmaster of Eton College.[3] During his time as curate to Keate he published research on the Eikon Basilike and the Greek New Testament.[1] In 1827 he was appointed to the parish of Farnham by Charles Sumner, Bishop of Winchester, and was then given the position of chaplain at the Tower of London.[1][3]

Broughton was a Tory and a high churchman, and was opposed to the growing movement towards political and theological liberalism.[7][8] He was a defender of the doctrine of Apostolic succession, the importance of the Eucharist, and Royal Supremacy over the Church of England.[9][5] He also held strong anti-Catholic sentiments and was an opponent of Catholic emancipation.[10] Later in his life, he would flirt with Tractarianism—a high church or Anglo-Catholic theological movement that began at Oxford University.[1][11]

Remove ads

Career in Australia

Summarize

Perspective

In 1829, after being appointed Archdeacon of New South Wales by Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, Broughton arrived in Sydney on the convict ship John.[3][1] He was unenthusiastic about taking up the role in Australia and was reluctant to accept it, writing in his journal as he approached Sydney that "the expected termination of our voyage...occasions no sensation of joy".[12][1] He moved into Tusculum, a villa in Potts Point, and was given positions on both the colony's Executive Council and Legislative Council.[13] Broughton would go on to have a significant impact on politics in New South Wales until his retirement from the legislature in 1843, particularly in the development of its immigration and land policy, and used his experience at the East India Company to become one of the most knowledgable figures on the colony's economy.[14] Broughton's theology placed him somewhat outside the norm in Australia, where most Anglicans were Evangelical in their beliefs. The colony's chaplain Samuel Marsden at one point said that Broughton's churchmanship made him "perhaps too high a churchman for our mixt population".[9]

At the time of Broughton's arrival in Sydney, then part of the Diocese of Calcutta, the city had a population of 10,000 and was home to two churches: St Philip's and St James'.[15] The Anglican church had long held a privileged position within the colony, but had begun to attract greater criticism, while the influence of the Catholic and Presbyterian churches had begun to grow.[1] In the 1820s, the Church and School Lands Corporation had been set up to take control of one seventh of the uncleared land in the colony in order to generate income for the church. But the corporation had struggled to generate an income from its lands.[16] Upon his arrival in Australia, Broughton learned that the Church and School Lands Corporation's charter had been suspended, and that the Anglican church's influence was waning and that the quality of church education was low.[1][17] The church was reliant on funding received from the government to maintain and grow its presence in the colony.[16]

Education reform and appointment as Bishop

Education within the colony quickly became a substantial concern for Broughton. In 1830 he issued a plan to establish King's Schools in Parramatta and Sydney; the school in Parramatta proved successful, while the school in Sydney quickly failed.[18][1] In 1831, the Irish liberal Richard Bourke had been appointed Governor of New South Wales. Bourke wished to establish a new model of education, modelled on the Irish National schools system, in which the three major churches—the Church of England, the Presbyterian Church and the Catholic Church—would be treated on more equal footing.[19] These state-funded schools would allow Christians of any denomination, with students receiving religious education directly from their respective denominations' ministers one day each week.[20] Broughton fiercely opposed the policy and believed that the Church of England should continue to be given special status and government support in educating the colony's children.[18][1]

In 1834, Broughton made a trip back to England to lobby for his position at the Colonial Office.[18] The Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, eventually approved Bourke's educational policy, while also supporting his proposal for the establishment of a new Diocese of Australia.[21] Broughton at first threatened to refuse the bishopric unless Bourke's government abandoned its education reforms.[22] But Broughton eventually accepted the position of Bishop, under the condition that he would not be associated with the new education policy.[23] Broughton was appointed the first Bishop of Australia and was consecrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Howley, at Lambeth Palace on 14 February 1836.[21] He was enthroned by Samuel Marsden on 5 June at St James' Church.[1]

Upon his return to Australia, despite Lord Glenelg's approval of Bourke's education policy, Broughton directed Anglican clergy and congregants to advocate against the proposed system. The fierce backlash prevented Bourke from enacting his planned reforms. It was not until 1847 that Broughton was forced by the dire financial position of the Anglican church's schools to allow the establishment of a parallel state-run educational body.[24][1]

Church Act of 1836

Soon after Broughton's return to Australia, Bourke passed the Church Act of 1836, subsidising clergy and religious buildings in the colony.[25] While his church stood to benefit from the Act, Broughton opposed Bourke's efforts at reform, which would allow for funding of all denominations on equal footing. He believed that the Anglican church, being the sole true religion, should be the sole recipient of government support.[26] He also protested throughout his time in Australia against the government's recognition of Catholic bishops.[27] While the Church of England received the largest sum of money under the new Church Act, it lost its semi-official status as the colony's established church.[28]

The Act enabled Broughton to recruit a large number of new clergymen, who were offered stipends to immigrate to Australia.[29] The number of clergymen in Australia would quintuple between 1836 and 1850, driven in part by an increasing oversupply of priests within Britain.[30] In the 1840s, Broughton supported the establishment of a grammar school and short-lived theological college to train Australian men for the priesthood.[1][31] The Church Act also allowed for the establishment of a significant number of new church buildings; about 100 new churches across Australia were dedicated or consecrated by Broughton during his time as bishop.[1] Despite his long-standing difficulties walking and his frequent use of a cane, he travelled extensively throughout the colony, consecrating church buildings across New South Wales.[1][32] In 1837 Broughton began the construction of St. Andrew's Cathedral, which would not be completed until after his death.[1]

Church government and later life

Broughton supported the establishment of a number of other bishoprics in Oceania in the 1840s, including in New Zealand, Tasmania, Melbourne, Newcastle and Adelaide.[1] In 1847, after three new bishops were consecrated in a ceremony at Westminster Abbey, Broughton became Bishop of Sydney and Metropolitan of Australasia.[33] This growth of the Australasian church increased the urgency of resolving unanswered questions of ecclesiastical government, the application of canon law, and the relationship between church and state.[1] Broughton was also concerned by the poor discipline of his clergymen after a number of scandals and incidents of misconduct.[34]

In 1850, Broughton held a meeting of Australasia's bishops in Sydney to decide the church's governance structure.[1] The meeting, which was held at Tusculum, was not a formal assembly and had no power to issue decrees.[1][35] But the bishops reached agreement on a number of principles, including for education, church government and clerical discipline.[1] One of their decisions was that the church should establish synods of bishops and priests at the provincial level and for each diocese, supported by conventions of laymen that would hold little decision-making authority.[36] The recommendation provoked backlash from the laity, who regarded the meeting of the bishops as evidence of "episcopal tyranny" and "clerical supremacy".[1] Broughton sailed to England in 1852 to discuss the future of the Australian church and to gain the British government's support for his proposed church constitution. He became ill on the journey and died in London on 20 February 1853.[1][37] He was buried at Canterbury Cathedral, becoming the first priest since the Reformation to be buried in the cathedral.[37]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads