Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Shin (letter)

Twenty-first letter in many Semitic alphabets From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

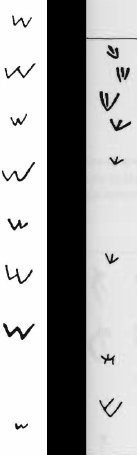

Shin (also spelled Šin (šīn) or Sheen) is the twenty-first and penultimate letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician šīn 𐤔, Hebrew šīn ש, Aramaic šīn 𐡔, Syriac šīn ܫ, and Arabic sīn س.[a][b]

The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek Sigma (Σ) (which in turn gave rise to the Latin S, the German ẞ and the Cyrillic С), and the letter Sha in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts (![]() , Ш). The South Arabian and Ethiopian letter Śawt is also cognate. The letter šīn is the only letter of the Arabic alphabet with three dots with a letter corresponding to a letter in the Northwest Semitic abjad or the Phoenician alphabet.

, Ш). The South Arabian and Ethiopian letter Śawt is also cognate. The letter šīn is the only letter of the Arabic alphabet with three dots with a letter corresponding to a letter in the Northwest Semitic abjad or the Phoenician alphabet.

Remove ads

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

The Proto-Sinaitic glyph, according to William Albright, was based on a "tooth" and with the phonemic value š "corresponds etymologically (in part, at least) to original Semitic ṯ (th), which was pronounced s in South Canaanite".[5] However, the Proto-Semitic word for "tooth" has been reconstructed as *šinn-.[6]

The Phoenician šin letter expressed the continuants of two Proto-Semitic phonemes, and may have been based on a pictogram of a tooth (in modern Hebrew shen).

The history of the letters expressing sibilants in the various Semitic alphabets is somewhat complicated, due to different mergers between Proto-Semitic phonemes. As usually reconstructed, there are nine Proto-Semitic coronal fricative phonemes that evolved into the various sibilants of its daughter languages, as follows:

Remove ads

Arabic shīn

Summarize

Perspective

Based on Semitic linguists (hypothesized), Samekh has no surviving descendant in the Arabic alphabet, and that sīn is derived from Phoenician šīn 𐤔 rather than Phoenician sāmek 𐤎, but it corresponds exclusively to Arabic س Sīn when comparing etymologically to other Semitic languages. In the Mashriqi abjadi order س Phonecsīn takes the place of Samekh at 15th position;[c] meanwhile, the ش shīn is placed at the 21st position, represents /ʃ/, and is the 13th letter of the modern hijā’ī (هِجَائِي) or alifbāʾī (أَلِفْبَائِي) order and is written thus:

In the Arabic alphabet, according to McDonald (1986), "there can be no doubt that ش is a formal derivative of س and that س is descended from 𐡔."[4] but unlike the Hebrew ש Sīn/Šīn and Aramaic 𐡔 Sīn/Šīn, Arabic س Sīn is considered a completely separate letter from ش Šīn /ʃ/.

The Arabic letter shīn was an acronym for "something" (شيء shayʾ(un) [ʃajʔ(un)]) meaning the unknown in algebraic equations. In the transcription into Spanish, the Greek letter chi (χ) was used which was later transcribed into Latin x. The letter shīn, along with Ṯāʾ, are the only two surviving letters in Arabic with three dots above. According to some sources, this is the origin of x used for the unknown in the equations.[8][9] However, according to other sources, there is no historical evidence for this.[10][11] In Modern Arabic mathematical notation, س sīn, i.e. shīn without its dots, often corresponds to Latin x. This led a debate to many Semitic linguists that the letter shīn is Arabic for samekh, although many Semitic linguists argue this debate as samekh has no surviving descendant in the Arabic alphabet.

In the Maghrebian abjad sequence :

- ص Ṣād replaces Samekh at 15th position and retains the numerical value of 60;

- س Sīn replaces Šīn at 21st position and retains the numerical value of 300.

- ش Šīn takes the places of the 28th letter with a numerical value of 1000.

Remove ads

Aramaic shin/sin

In Aramaic, where the use of shin is well-determined, the orthography of sin was never fully resolved.

To express an etymological *ś, a number of dialects chose either sin or samek exclusively, where other dialects switch freely between them (often 'leaning' more often towards one or the other). For example:[12]

Regardless of how it is written, *ś in spoken Aramaic seems to have universally resolved to /s/.

Hebrew shin/sin

Summarize

Perspective

Hebrew spelling: שִׁין

The Hebrew /s/ version according to the reconstruction shown above is descended from Proto-Semitic *ś, a phoneme thought to correspond to a voiceless alveolar lateral fricative /ɬ/, similar to Welsh Ll in "Llandudno" (Welsh: [ɬanˈdɨdnɔ] ⓘ).

See also Hebrew phonology, Śawt.

Sin and Shin dot

The Hebrew letter represents two different phonemes: a sibilant /s/, like English sour, and a /ʃ/, like English shoe. Prior to the advent and ascendancy of Tiberian orthography, the two were distinguished by a superscript samekh, i.e. ש vs. שס, which later developed into the dot. The two are distinguished by a dot above the left-hand side of the letter for /s/ and above the right-hand side for /ʃ/. In the biblical name Issachar (Hebrew: יִשָּׂשכָר) only, the second sin/shin letter is always written without any dot, even in fully vocalized texts. This is because the second sin/shin is always silent.

Unicode encoding

Significance

In gematria, Shin represents the number 300. The breakdown of its namesake, Shin[300] - Yodh[10] - Nunh[50] gives the geometrical meaningful number 360, which can be interpreted as encompassing the fullness of the degrees of circles.

Shin as a prefix commonly used in late-Biblical and Modern Hebrew language carries similar meaning as specificity faring relative pronouns in English: "that (..)", "which (..)" and "who (..)". When used this way, it is pronounced as 'sheh-' (IPA /ʃɛ-/. In colloquial Hebrew, Kaph and Shin together are a contraction of כּאשר, ka'asher (as, when).

Shin is also one of the seven letters which receive “crowns” (called tagin) in a Sefer Torah. (See Gimmel, Ayin, Teth, Nun, Zayin, and Tzadi).

According to Judges 12:6, the tribe of Ephraim could not differentiate between Shin and Samekh; when the Gileadites were at war with the Ephraimites, they would ask suspected Ephraimites to say the word shibboleth; an Ephraimite would say sibboleth and thus be exposed. This episode is the origin of the English term shibboleth.

In Judaism

Shin also stands for the word Shaddai, a Name of God. A kohen forms the letter Shin with each of his hands as he recites the Priestly Blessing. In the mid-1960s, actor Leonard Nimoy used a single-handed version of this gesture to create the Vulcan hand salute for his character, Mr. Spock, on Star Trek.[15][16]

The letter Shin is often written on the case of a mezuzah, a scroll of parchment containing select Biblical texts. Sometimes the whole word Shaddai will be written.

The Shema Yisrael prayer also commands the Israelites to write God's commandments on their hearts (Deut. 6:6); the shape of the letter Shin mimics the structure of the human heart: the lower, larger left ventricle (which supplies the full body) and the smaller right ventricle (which supplies the lungs) are positioned like the lines of the letter Shin.

A religious significance has been applied to the fact that there are three valleys that comprise the city of Jerusalem's geography: the Valley of Ben Hinnom, Tyropoeon Valley, and Kidron Valley, and that these valleys converge to also form the shape of the letter shin, and that the Temple in Jerusalem is located where the dagesh (horizontal line) is. This is seen as a fulfillment of passages such as Deuteronomy 16:2 that instructs Jews to celebrate the Pasach at "the place the LORD will choose as a dwelling for his Name" (NIV).

In the Sefer Yetzirah the letter Shin is King over Fire, Formed Heaven in the Universe, Hot in the Year, and the Head in the Soul.

The 13th-century Kabbalistic text Sefer HaTemunah, holds that a single letter of unknown pronunciation, held by some to be the four-pronged shin on one side of the teffilin box, is missing from the current alphabet. The world's flaws, the book teaches, are related to the absence of this letter, the eventual revelation of which will repair the universe.

In Russian

The corresponding letter for the /ʃ/ sound in Russian is nearly identical in shape to the Hebrew shin. Given that the Cyrillic script includes borrowed letters from a variety of different alphabets such as Greek and Latin, it is often suggested that the letter sha is directly borrowed from the Hebrew letter shin (other hypothesized sources include Coptic and Samaritan).

Hebrew terms containing Shin

Shin Bet is a commonly used acronym for the Israeli Department of Internal General Security. Despite referring to a former name of the department, it remains the term usually used in English. In Modern Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic, the security service is known as the Shabak.

A Shin-Shin clash is Israeli military parlance for a battle between two tank divisions (from Hebrew: שִׁרְיוֹן, romanized: shiryon, lit. 'armour').

Sh'at haShin ('Shin hour') is the last possible moment for any action, usually in a military context. Corresponds to the English expression eleventh hour.

Remove ads

Syriac shin

Character encodings

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- The position of Arabic shīn ش is 21st in the common abjadi order (according to the Arab Grammarian Adnan Al-Khatib it's the older and more correct order),[2] and the 28th in the Maghrebian abjadi order (quoted by apparently earliest authorities and considered older according to Macdonald); its numerical value is 300 in the common abjadi order, and 1000 in the Maghrebian abjad order.[3] Its sound value is a [ʃ].

- Which is occupied by ص ṣad in the Maghrebian abjadi order.

Remove ads

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads