Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

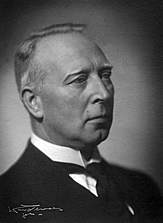

Sigmund Mowinckel

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sigmund Olaf Plytt Mowinckel (4 August 1884 – 4 June 1965) was a Norwegian professor, theologian and biblical scholar. He was noted for his research into the practice of religious worship in ancient Israel.[1]

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Mowinckel was born at Kjerringøy in 1884[2] and was educated at the University of Oslo (1908; Th.D. 1916).[3] His early research interests were study of the Old Testament and Assyriology.[2] In the years 1911-13 he made study trips to Copenhagen, Marburg and Giessen.[2] At Giessen he came into contact with Hermann Gunkel and was inspired by Gunkel's understanding of the Old Testament as literature, as well as his traditio-historical method.[2]

In 1916 he published his doctoral thesis on the prophet Nehemiah, and a companion work on the prophet Ezra.[2] In the years 1921-24 he published Psalmenstudien, maybe his most influential work.[2] As an Old Testament scholar he was particularly interested in the Psalms and the ancient cult of Israel. [2]According to Clements,[4] "Mowinckel continually developed and revised his views, notably on Israelite kingship and Psalmody". In 1956 he published "He That Cometh: The Messiah Concept in the Old Testament and Later Judaism".[5][6] For most of his professional life Mowinckel was connected to the University of Oslo and continued to lecture there as an emeritus in the 1960's.[2] Among his students we find the norwegian biblical scholar Arvid Kapelrud.[2] His last book in english, "Religion and Cult", was published in 1981.[7]

Remove ads

Academic work and theories

Summarize

Perspective

Mowinckels main contribution to biblical scholarship is his work on The Psalms of the Old Testament and his study of Messianic ideas in Judaism.

The Psalms

From the 1920s, Mowinckel headed a school of thought concerning the Book of Psalms which sometimes clashed with the Form criticism conclusions of Hermann Gunkel and those who followed in Gunkel's footsteps. In broad terms, Gunkel strongly advocated a view of the Psalms which focused on the two notable names for God occurring therein: Yahweh (JHWH sometimes called tetragrammaton) and Elohim. The schools of Psalm writing springing therefrom were termed Yahwist and Elohist. Mowinckel's approach to the Psalms differed quite a bit from Gunkel's. Mowinckel explained the Psalms as wholly cultic, both in origin and in intention. He attempted to relate more than 40 psalms to a hypothetical New Year autumn festival,[8][9] the so-called "Enthronement Festival of Yahweh".[10] According to Mowinckel the Psalms had a practical usage in the context of the Temple service.[11] He also suggests that the authors of the Psalms were temple singers.[12] As for the Psalms that have no cultic context, Mowinckel identifies these as the "wisdom psalms".[12]

Messianic ideas

In addition to his work on Psalms, his major monograph on the Old Testament roots of Messianism is of significance in scholarship until this day.[13] In his study of Messianism in ancient Israel, and the Ancient Near East, Mowinckel identified the concept of divine kingship.[14] He did however deny the title of Messiah to the reigning Hebrew kings, although they reflected the Messianic ideal.[15] The kings were associated with divinity, but Mowinckel does not support the view that they were an incarnation of the deity, or that they represented a suffering, dying and rising god.[15] The Israelites adapted some ideas on kingship from Canaanite sources, combined with traditions of old nomadic chieftainship and Yahwism.[16] According to Mowinckel the concept of Kingship is associated with the present, while the Messiah is a future being,[16] associated with eschatology.[17] The Hebrew royal line is therefore, in his view, not Messianic,[17] and there is no eschatology prior to the Babylonian exile.[17]

Mowinckel also considers the songs of the Suffering Servant in the Old Testament. Mowinckel accepts the common understanding of the servant songs, according to tradition, as signifying atonement and vicarious suffering. [17] He identifies the servant as a historical character from the circle surrounding Isaiah and Second Isaiah.[14] However, he does not rule out that the servant could be a future character.[17][14] He finds the servant free of kingly traits [15] and concludes that the songs were not originally meant to be Messianic. [16] The suffering servant is therefore, according to Mowinckel, something else than a Messiah, he is a «mediator of salvation»[17]

The Son of Man, on the other hand, is an eschatological figure,[17] influenced by Messianic ideas.[15] According to Ceroke[17] «The Son of Man is in Mowinckel’s treatment the culmination of messianism». However, Mowinckel disagrees with other scholars, such as Joachim Jeremias, that the Son of Man represents an atoning suffering and death.[17] Martin[16] notes that Mowinckels approach to the subject is historical, not theological or doctrinal. As a consequence of this Martin finds that Mowinckels handling of the subject is a bit incomplete in light of the entire message of Jesus and his (Jesus') use of the term Son of Man.

Mowinckel suggests that Jesus adapted both the concept of the Son of Man and the figure of the Servant, but in a paradoxical way.[16] The concept of the Messiah is modified in order to suit his ministry and his understanding of himself. He merges the redeeming element of the Son of Man with the idea of the suffering Servant. [16][17] According to Muilenburg[14] «Mowinckel believes that Jesus himself was the first to understand the real meaning of Isaiah 53 and to apply it to himself». Despite expressing criticism toward several aspects of Mowinckels work on this subject, several reviewers [15][16][17] found his treatment of Messianic ideas to be a solid contribution to Old Testament Scholarship.

Remove ads

Selected works

- Statholderen Nehemia (Kristiania: a. 1916)

- Esra den skriftlærde (Kristiania: a. 1916)

- Kongesalmerne i det Gamle Testamentet (Kristiania: (1916)

- Der Knächt Jahves (1921)

- Psalmenstudien I: 'Awan und die individuellen Klagepsalmen (Kristiania: SNVAO, 1921)Note a

- Psalmenstudien II: Das Thronbesteigungsfest Jahwäs und der Ursprung der Eschatologie (Kristiania: SNVAO, 1922)Note a

- Psalmenstudien III: Kultprophetie und kultprophetische Psalmen (Kristiania: SNVAO, 1923)Note a

- Psalmenstudien IV: Die technischen Termini in den Psalmenuberschriften (Kristiania: SNVAO, 1923)Note a

- Psalmenstudien V: Segen und Fluch in Israels Kult und Psalmdichtung (Kristiania: SNVAO, 1924)Note a

- Psalmenstudien VI: Die Psalmdichter (Kristiania: SNVAO, 1924)Note a

- Han som kommer : Messiasforventningen i Det gamle testament og på Jesu tid (1951)

- He That Cometh: The Messiah Concept in the Old Testament and Later Judaism (trans. G. W. Anderson. Oxford: B.Blackwell, 1956)

- The Spirit and the Word: Prophecy and Tradition in Ancient Israel. Edited by K. C. Hanson. Fortress Classics in Biblical Studies (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002)

Selected articles

- 'Om den jodiske menighets og provinsen Judeas organisasjon ca. 400 f. Kr.', Norsk Teologisk Tidsskrift (Kristiania: 1915), pp. 123ff., 226ff.

- 'Det kultiske synspunkt som forskningsprinsipp i den gammelstestamentlige videnskap', Norsk Teologisk Tidsskrift (Kristiania: 1924), pp. 1ff.

- 'I porten' Studier tilegnede Frans Buhl (Copenhagen: 1925)

- 'Levi und Leviten' [translation: "Levi and Levites"], RGG2 [appeared in Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart 2.Aufl.] (Tübingen: 1927-32)

- 'Stilformer og motiver i profeten Jeremias dikning', Edda Vol. 36 (1926), pp. 276ff.

- 'A quelle moment le culte de Jahwe a Jerusalem est il officiellement devenu un culte sans images?' [translation: "At what moment did the cult of Jahweh of Jerusalem officially become a cult without images?"] Revue de l'Histoire et des Philosophies Religieuses Vol. 9 (Strasbourg: 1929), pp. 197ff.

- 'Die Komposition des Deuterojesajanischen Buches' [translation: "The Composition of the book of Deutero-Isaiah"], Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft Band (Vol.) 44 (Giessen: 1931)pp. 87ff., 242ff.

- 'Die Chronologie der israelitischen und judaischen Konige' [translation: "The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah"], Acta Orientalia Vol. 10 (Leiden: 1932) pp. 161ff.

- 'The "Spirit" and the "Word" in the Pre-exilic Reforming Prophets', Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 53 (1934) pp. 199–227.

- 'Extatic Experience and Rational Elaboration in Old Testament Prophecy', Acta Orientalia Vol. 13 (Leiden: 1935), pp. 264–291.

- 'Hat es ein israelitisches Nationalepos gegeben?' [translation: "Is there a given Israelite national epic?"], Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft Band (Vol.) 53 (Giessen: 1935) pp. 130ff.

- 'Zur Geschichte der Dekalogue' [translation: "To a History of the Decalogue (Ten Commandments)"], Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft Band (Vol.) 55 (Giessen: 1937) pp. 218ff.

- 'Ras Shamra og det Gamle Testament', Norsk Teologisk Tidsskrift Vol. xl, (Oslo: 1939), pp. 16ff.

- 'Oppkomsten av profetlitteraturen', Norsk Teologisk Tidsskrift (Oslo: 1942), pp. 65ff.

- 'Zur hebraischen Metrik II' [translation: "Towards Hebrew Metric II"], Studia theologica cura ordinum theologorum Scandinavorum edita Vol. VII (1953), pp. 54ff.

- 'Der metrische Aufbau von Jes. 62, 1 - 12 und die neuen sog. kurzverse' [translation: "The metrical construction of Isaiah 62: 1 - 12 and the new so-called ? shortverse"], Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft' Band (Vol.) 65 (Giessen: 1953), pp. 167ff.

- 'Zum Psalm des Habakuk' [translation: "Towards the Psalm of Habakkuk"], Theologische Zeitschrift Band (Vol.) 9 (Basel: 1953), pp. 1ff.

- 'Psalm Criticism between 1900 and 1935 (Ugarit and Psalm Exegesis)', Vetus Testamentum Vol. 5 (Leiden: Brill, 1955) pp. 13ff.

- 'Marginalien zur hebraischen Metrik', Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft' Band (Vol.) 67 (Giessen: 1956) pp. 97ff.

- 'Zu Psalm 16, 3 - 4' [translation: "To/towards Psalm 16: 3 - 4"], Theologische Literaturzeitung (1957), columns 649ff.

- 'Notes on the Psalms', Studia theologica cura ordinum theologorum Scandinavorum edita' Vol. XIII (1959), pp. 134ff.

- 'Drive and/or Ride in the O.T.', Vetus Testamentum Vol. 12 (Leiden: Brill, 1962) pp. 278–299ff.

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- :a.^ SNVAO signifies the Norwegian publisher/publications Skrifter utgitt av Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo, II. Hist.-Filos. Klasse.

References

Other sources

Related Reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads