Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

History of ancient Israel and Judah

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The history of ancient Israel and Judah spans from the early appearance of the Israelites in Canaan's hill country during the late second millennium BCE, to the establishment and subsequent downfall of the two Israelite kingdoms in the mid-first millennium BCE. This history unfolds within the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. The earliest documented mention of "Israel" as a people appears on the Merneptah Stele, an ancient Egyptian inscription dating back to around 1208 BCE. Archaeological evidence suggests that ancient Israelite culture evolved from the pre-existing Canaanite civilization. During the Iron Age II period, two Israelite kingdoms emerged, covering much of Canaan: the Kingdom of Israel in the north and the Kingdom of Judah in the south.[1]

This article may incorporate text from a large language model. (November 2025) |

According to the Hebrew Bible, a "United Monarchy" consisting of Israel and Judah existed as early as the 11th century BCE, under the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon; the great kingdom later was separated into two smaller kingdoms: Israel, containing the cities of Shechem and Samaria, in the north, and Judah, containing Jerusalem and Solomon's Temple, in the south. The historicity of the United Monarchy is debated—as there are no archaeological remains of it that are accepted as consensus—but historians and archaeologists agree that Israel and Judah existed as separate kingdoms by c. 900 BCE[2]: 169–195 [3] and c. 850 BCE,[4] respectively.[5] The kingdoms' history is known in greater detail than that of other kingdoms in the Levant, primarily due to the selective narratives in the Books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles, which were included in the Bible.[1]

The northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed around 720 BCE, when it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[6] While the Kingdom of Judah remained intact during this time, it became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then the Neo-Babylonian Empire. However, Jewish revolts against the Babylonians led to the destruction of Judah in 586 BCE, under the rule of Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. According to the biblical account, the armies of Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem between 589 and 586 BCE, which led to the destruction of Solomon's Temple and the exile of the Jews to Babylon; this event was also recorded in the Babylonian Chronicles.[7][8] The exilic period saw the development of the Israelite religion towards a monotheistic Judaism.

The exile ended with the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid Empire c. 538 BCE. Subsequently, the Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great issued a proclamation known as the Edict of Cyrus, which authorized and encouraged exiled Jews to return to Judah.[9][10] Cyrus' proclamation began the exiles' return to Zion, inaugurating the formative period in which a more distinctive Jewish identity developed in the Persian province of Yehud. During this time, the destroyed Solomon's Temple was replaced by the Second Temple, marking the beginning of the Second Temple period.

Remove ads

Periods

In archaeological terms, the history covered in this article falls within the Iron Age, which is commonly divided into two main phases (noting that precise dates are subject to scholarly debate):

Alternate terminology for this timeframe includes:

- First Temple period (or Israelite period): (c. 1000 – 586 BCE)[14]

These periods correspond to the emergence, development, and eventual fall of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The Iron Age II ends with the Babylonian conquest of Judah in 587/6 BCE. Following Iron Age II, periods are often named after dominant imperial powers. For example, the Babylonian period (586–539 BCE) is named for the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which conquered Judah and exiled much of its population. The return to Zion and the construction of the Second Temple marked the beginning of the Second Temple period (c. 516 BCE – 70 CE).

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Geography

The eastern Mediterranean seaboard stretches 400 miles (640 km) north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai Peninsula, and 60 to 90 miles (97 to 145 km) east to west between the sea and the Arabian Desert.[15] The coastal plain of the southern Levant, broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the Shfela; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of Mount Carmel. East of the plain and the Shfela is a mountainous ridge, the "hill country of Judea" in the south, the "hill country of Ephraim" north of that, then Galilee and Mount Lebanon. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the wadi of the Arabah, which continues down to the eastern arm of the Red Sea. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. The location and geographical characteristics of the narrow Levant made the area a battleground among the powerful entities that surrounded it.[16]

Late Bronze Age Canaan

Ancient Israel emerged during the late second millennium BCE. Canaan, as the region was known in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1500–1200 BCE), was then a patchwork of city-states under the imperial domination of the New Kingdom of Egypt. During this period, Canaan was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand.[17] Settlement was concentrated in cities along the coastal plain and along major communication routes; the central and northern hill country which would later become the biblical kingdom of Israel was only sparsely inhabited.[18] The Amarna letters, discovered in Egypt, offer insight into regional politics and mention cities such as Ashkelon, Hazor, Gezer, Shechem, Jerusalem, and Megiddo.[19] Several of these city-states were embroiled in rivalries and territorial disputes, with local rulers like Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem and Lab'ayu of Shechem appealing to the pharaoh for assistance against neighboring leaders.[19][20]

Alongside the city-states, Late Bronze Age texts mention other groups inhabiting the region.[21] The 'Apiru were a marginalized social class that included migrants, mercenaries, and others living on the fringes of society.[22] As the word 'Apiru is possibly related linguistically to the term "Hebrew," early scholars equated them with the Israelites, but most now view any connection as indirect: while some early Israelites may have come from Apiru-like backgrounds, the term "Hebrew" later developed into a distinct ethnic identity.[21][23] The Shasu, often associated with pastoralist groups east of the Dead Sea, are sometimes linked to early Israel—particularly due to an Egyptian reference that names them alongside a term resembling Yahweh,[a] which some scholars see as a reference to the Israelite deity.[22] Some texts describe these groups as tribal or settled communities, possibly indicating ethnic identities and suggesting that the Egyptians may have grouped diverse populations under a single label.[22]

Late Bronze Age collapse

Around 1200 BCE, the entire Eastern Mediterranean was impacted by the Late Bronze Age collapse, a period of widespread upheaval marked by population movements, invasions, urban destruction, and the fall of major powers, including the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite Empire, and Egypt's New Kingdom.[25] Scholars attribute these disruptions to war, famine, plague, climate change, invasions, or a combination of factors.[25] Canaan was affected too,[26] its large cities were devastated, setting the stage for a new era in the region's history. The process was gradual,[27] and some Canaanite cities survived into Iron Age I.[28]

Around 1140 BCE, Egypt lost control over Canaan, and various groups of Sea Peoples settled along its coastal regions.[29] Among them were the Peleset, who are widely considered to be the biblical Philistines, settling in the southern coastal plain, west of Judah.[30] Their material culture, genetic evidence, and the biblical narrative all point to an Aegean or Cypriot origin.[30] It is in this later part of the Late Bronze Age that a people called Israel are first attested.[31]

Remove ads

Origins of ancient Israel

Summarize

Perspective

Biblical account

The Hebrew Bible chronicles the descent of the Israelites from the Patriarchs. The Book of Genesis describes how Abraham, under God's guidance, migrated from Mesopotamia to Canaan and entered into a covenant with God, who promised to make his descendants a chosen people and grant them the land of Canaan as an eternal inheritance. The narrative continues with the lives of his son Isaac and grandson Jacob, who was renamed Israel after wrestling with an angel.[32] The twelve sons of Israel moved to Egypt during a famine, and their descendants, the Twelve Tribes of Israel, were enslaved by the pharaoh.[32] After generations of bondage, Moses, an Israelite from the Tribe of Levi raised in the Egyptian court, led the Israelites out during The Exodus—their deliverance from slavery in Egypt.[32] Following a miraculous crossing of the Red Sea, the giving of the Law at Mount Sinai, and forty years of wandering in the wilderness, Moses died as the Israelites reached the threshold of Canaan.[32] Under his successor Joshua, the Israelites crossed the Jordan River and began the conquest of Canaan. The land was allotted among the tribes and distributed to families as inheritance, but in the absence of centralized authority, the tribes were left to confront local populations on their own.[33] During the era of the Judges (as the Bible calls it), the Israelites existed as a loose tribal confederation in the hill country, without a centralized government, but with judges. The Book of Judges is thought to reflect early Israelite tribal society.[34]

Archaeological and scholarly perspectives

Modern scholarship generally views ancient Israel's origins as emerging primarily from the indigenous population of Canaan.[35][36] According to this view, the early Israelites likely consisted of diverse elements drawn from Late Bronze Age society, including rural villagers, former settled peoples, displaced peasants, and pastoralist groups.[37][35] These were joined by marginal segments of society, such as the 'Apiru and Shasu, who lived on the fringes of settled areas.[37][35][b] Additional external elements may have included fugitive or runaway Semitic slaves from Egypt, who likely constituted at least part of the emerging Israelite population.[35][39][40]

At the same time, scholars argue that the Exodus story may preserve a kernel of historical truth, though it has been reshaped over time. Various Semitic peoples lived in Egypt at different periods, and the biblical narrative could reflect the experiences of a particular group which was later expanded into a national saga.[41] The Egyptian origin of Moses's name, as well as the presence of other Egyptian names within the Levite tribe (including Hophni and Phinehas), suggests an authentic Egyptian connection.[41] Additionally, the story's references to brickmaking, the mention of city of Ramesses (linked to Ramesses II) and the route taken by the Israelites align with the reality of the Late Bronze Age.[41] Some scholars propose that multiple groups left Egypt at different times, while others suggest the Exodus traditions reflect the memories of refugees displaced during Egypt's withdrawal from Canaan.[41] The conquest story under Joshua, particularly regarding Jericho, et-Tell (identified with the biblical Ai), and Gibeon, is often described as being contradicted by archaeological evidence, as these cities were unoccupied during the relevant periods, though Hazor's destruction layer does align with the biblical account.[24]

While biblical texts often portray Israel as opponents of the Canaanites, scholars note that much of Israel's heritage was deeply Canaanite in character—culturally, linguistically, and religiously. Some of the Bible's earliest compositions, such as the Song of the Sea and the Song of Deborah, seem to have Canaanite roots.[42] The Hebrew language is referred to in the Book of Isaiah as the "lip of Canaan",[43] and was closely related to neighboring dialects like Phoenician and Moabite.[42] Alongside material continuity with Late Bronze Age Canaan[44]—albeit with some distinctive developments—the early Israelite religion also mirrored typical Canaanite traditions.[42] Other scholars dispute the idea of a purely Canaanite origin for the Israelites, pointing to distinctive practices that set them apart.[45] These include the settlement of small, unwalled hill villages, in contrast to the larger, walled towns typically found in the plains during the Canaanite period.[45] The Israelites also displayed unique pottery styles, characterized by the absence of painted or imported pottery in the hills.[45] Additionally, the Israelites avoided consuming pig meat, unlike the Canaanites and Philistines, and their religious practices lacked Canaanite-style temples, with limited evidence of organized cultic activity.[45]

Remove ads

Iron Age I (13th–11th centuries BCE)

Summarize

Perspective

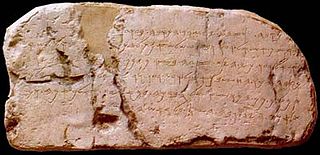

The Merneptah Stele

The earliest extra-biblical reference to Israel appears on the Merneptah Stele, also known as the "Israel stele",[46] an Egyptian inscription dated to c. 1208 BCE. It records Israel among Pharaoh Merneptah's military victories in Canaan, stating, "Israel is laid waste, his seed is not." A hieroglyphic marker classifies Israel as a semi-nomadic or rural people, distinguishing it from the fortified cities also listed in the inscription. The inclusion of Israel among notable defeated enemies suggests that the group was already an entity of significance in Canaan by the late 13th century BCE.[47]

Highland settlement and material culture

By the 13th–12th centuries BCE, new villages began to appear in the central hill country, particularly in the region between Jerusalem and Shechem,[48] which scholars identify as the earliest Israelite settlements. These villages were typically unwalled,[48] and contained only a few hundred inhabitants each. The sites exhibit continuity with Late Bronze Age culture, including in most pottery forms,[44] while also displaying changes: the usage of collared-rim jars, the absence of pig bones (possibly reflecting dietary practices), and the development of four-room house architecture, a feature unique to Israelite settlements. Many of these settlements were established on hilltops, with economies based on terraced agriculture adapted to the slopes.[48]

Around this period, substantial settlement is attested archaeologically in the highlands of central Canaan. In the Late Bronze Age there were no more than about 25 villages in the highlands, but this increased to over 300 by the end of Iron Age I, while the settled population doubled from 20,000 to 40,000.[49] The villages were more numerous and larger in the north, and probably shared the highlands with pastoral nomads, who left no remains.[50] Archaeologists and historians attempting to trace the origins of these villagers have found it impossible to identify any distinctive features that could define them as specifically Israelite – collared-rim jars and four-room houses have been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites,[51] and while the pottery of the highland villages is far more limited than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.[52] Israel Finkelstein proposed that the oval or circular layout that distinguishes some of the earliest highland sites, and the notable absence of pig bones from hill sites, could be taken as markers of ethnicity, but others have cautioned that these can be a "common-sense" adaptation to highland life and not necessarily revelatory of origins.[53] Other Aramaean sites also demonstrate a contemporary absence of pig remains at that time, unlike earlier Canaanite and later Philistine excavations.

Daily life in the highlands

Extensive archaeological excavations have provided a picture of Israelite society during the early Iron Age period. The archaeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population. During this period, Israelites lived primarily in small villages, the largest of which had populations of up to 300 or 400.[54][55] Their villages were built on hilltops. Their houses were built in clusters around a common courtyard. They built three- or four-room houses out of mudbrick with a stone foundation and sometimes with a second story made of wood. The inhabitants lived by farming and herding. They built terraces to farm on hillsides, planting various crops and maintaining orchards. The villages were largely economically self-sufficient and economic interchange was prevalent. According to the Bible, prior to the rise of the Israelite monarchy the early Israelites were led by the Biblical judges, or chieftains who served as military leaders in times of crisis. Scholars are divided over the historicity of this account. However, it is likely that regional chiefdoms and polities provided security. The small villages were unwalled but were likely subjects of the major town in the area. Writing was known and available for recording, even at small sites.[56][57][58][59][60]

Early Israelite organization

Unlike the city-state model, Israelite society was organized around kinship-based tribes that controlled parcels of land and operated independently, though they could unite when faced with external threats.[61] Early biblical texts, such as the Song of Deborah, indeed depict Israel as a confederation of loosely allied tribes.[61] The tribal structure appears fluid, with varying lists of tribes and occasional absences—most notably Judah, which seems to have maintained a distinct identity at this time.[61] A shared sense of kinship among the tribes appears to have shaped how they related to others and likely served as one motivating force behind their eventual unification.[61] In parallel, clashes with the Philistines may have pushed the tribes to cooperate more closely, contributing to the formation of a collective identity and ultimately a state.[62]

Remove ads

The United Monarchy

Summarize

Perspective

Biblical account

According to biblical tradition, the Israelite tribes eventually united under a centralized monarchy in the late 11th to 10th century BCE, forming what is often called the United Monarchy. The first king was Saul, from the tribe of Benjamin, who led Israel in battle against enemies in the region. After Saul died by suicide following a defeat against the Philistines, King David, a Judahite from Bethlehem, ascended to the throne (c. 1005 BCE).[63] David captured Jerusalem, establishing it as his capital and bringing the Ark of the Covenant there.[64] Under his rule, Jerusalem was likely a royal enclave rather than a large city, strategically located between Israel and Judah.[63] The Bible credits David with major military victories – defeating the Philistines[63] as well as the Transjordanian kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom. According to the Bible, he greatly expanded the kingdom's territory, forging a more cohesive state out of the tribes.

Under David and his son Solomon, who succeeded him around 970 BCE, Israel purportedly enjoyed a golden age of unity and prosperity. The Bible credits Solomon with wisdom, wealth, the establishment of administrative districts, and the commissioning of grand building projects.[65] Solomon is said to have built the First Temple in Jerusalem as a permanent house of worship to Israel's God.[64][c] This Temple, completed in the mid-10th century BCE, centralized the sacrificial cult and became the spiritual center of the nation. During Solomon's reign, the united kingdom of Israel reportedly extended its influence from the Euphrates River in the north to Egypt's border in the south, controlling key trade routes and enjoying regional prestige. He also reportedly established political and economic alliances, marrying foreign princesses and securing a trade partnership with Hiram of Tyre. In exchange for wheat and oil, Solomon received Lebanese cedar to build the Temple and his palace, while also developing a Red Sea port at Ezion-Geber (possibly modern Tell el-Kheleifeh[67]) to import luxury goods like gold, silver, and ivory.[68]

In modern scholarship

The historical reality of the United Monarchy is a subject of debate.[69] Since the 1980s, an approach increasingly skeptical of the biblical account of a united monarchy has emerged.[70][70] New methods in literary criticism state that the biblical texts were shaped by later theological and political agendas, raising doubts about their historical reliability.[71] Archaeological studies also challenged older interpretations: several structures once attributed to Solomon[72]—like gates at Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer—were redated or shown to lack clear ties to a centralized monarchy.[73] Some noted that Jerusalem appears to have been a small and modest settlement during the 10th century BCE.[69][74] Others have rejected the entire biblical narrative as a myth.[70]

Later discoveries have supported parts of the biblical account. In 1993, archaeologists at Tel Dan in northern Israel found the Tel Dan Stele, a fragmentary Aramaic inscription that references a "House of David," indicating that a dynasty of David was recognized by the 9th century BCE. This indicates that just over a century after David's presumed lifetime, he was already seen as the founder of Judah's royal lineage.[70] For example, archaeologist Eilat Mazar has argued that the so-called "Large Stone Structure" uncovered in Jerusalem belong to a 10th-century BCE royal complex, possibly King David's palace. However, this interpretation is debated, especially regarding the dating and whether the structures form a single unified complex.[75] Elsewhere, excavations at Khirbet en-Nahas in biblical Edom uncovered remains of a fortified copper production center, which some suggest points to centralized control—possibly linked to Solomon's reign—though the dating is disputed and may be later.[75]

A relatively recent piece of evidence that has influenced the debate comes from Khirbet Qeiyafa, a newly excavated fortified city overlooking the Elah Valley—the site of the biblical battle between David and Goliath.[76] Excavations conducted between 2007 and 2013 revealed a well-planned urban layout, administrative architecture, and a casemate wall, and radiocarbon dating places the site in the early 10th century BCE,[77] during the period traditionally associated with King David.[78] The material culture and dietary restrictions (evidenced by the absence of pig bones) were found to be closest to Judahite sites.[79][80] According to its excavators, led by Yosef Garfinkel, the findings suggest the existence of a centralized state in Judah in the 11th century BCE.[78] Inscriptions found there, as well as at Tel Zayit, including what may be early examples of Hebrew writing, have been cited as evidence for literacy and administrative activity in the 10th century BCE, possibly reflecting a centralized political structure.[81]

Literary analysis also supports the traditional view of an early, unified kingdom. As Benedikt Isserlin notes, if Israel and Judah were truly separate kingdoms, it would be difficult to understand why Judahites would refer to themselves as Israelites, especially considering that the northern kingdom was often Judah's enemy and condemned for its religious practices.[82] More significantly, the frequent reference to the deity worshipped in Jerusalem as "the God of Israel," rather than the god of Judah, suggests a shared heritage, which is most coherently explained by the biblical account of an early unified Israel.[82]

Some scholars, like Amihai Mazar, defend a more modest but real united monarchy, proposing that a unified Israelite kingdom likely did form in the 10th century BCE, but it may have been smaller and less centralized than the Bible depicts.[83] Mazar further notes that Pharaoh Shoshenq's campaign to the region c. 930 BCE, recorded by both the Bible and inscriptions in Egypt, indicates a significant political power in that area at the time, with the most reasonable candidate being a kingdom established by David and Solomon.[83] Others, like Israel Finkelstein, argue that state-level structures and territorial control only emerged in later centuries. Instead, Finkelstein proposed the "Low Chronology" model, which reassigns many architectural remains to the 9th century, during the Omride dynasty in the northern kingdom.[74] Finkelstein also argues that Shoshenk's campaign was directed at a tribal confederacy led by Saul in the Benjaminite area.[84] According to this view, David and Solomon were local hill-country chieftains than the leaders of a kingdom.[85] On the other hand, Yosef Garfinkel notes that the evidence from Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh, Tell en-Nasbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and Lachish allows for the reconstruction of 10th-century Judah as a centralized polity with urban centers and a territorial reach that extended up to a two-day walk from Jerusalem by the end of the century.[86] This model suggests that an organized kingdom, though smaller in scale, already existed during David's time.[86] Most agree that the biblical texts contain a blend of early memories and later elaborations, and while a large imperial kingdom is unlikely, a smaller political entity in the 10th century remains plausible.[83]

Remove ads

The Kingdoms of Israel and Judah (10th and 9th centuries BCE)

Summarize

Perspective

Political division and structure

According to the Bible, upon Solomon's death (c. 930 BCE), the northern tribes refused to accept his son Rehoboam as king, resulting in the division of the monarchy into two kingdoms.[87] There is firm evidence that by the 9th century BCE, two distinct successor states existed—though scholars debate whether they split from a previously united monarchy, as the biblical account suggests, or arose independently alongside one another. In either case, from this point forward, the history of Ancient Israel becomes the history of two kingdoms: the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. The larger Kingdom of Israel in the north consisted of ten tribes (with Joseph's tribes often dominant), and the smaller Kingdom of Judah in the south was comprised mainly the tribes of Judah and Benjamin.[87] In Israel, a former rebel against Solomon named Jeroboam led the secession and became the first king of the northern realm, while Rehoboam continued to rule Judah in the south.[87] For roughly two centuries, Israel and Judah co-existed as separate states – sometimes allied against common foes, but often rivals who even fought each other. Each kingdom had its own lineage of kings: Israel saw fast-changing dynasties and several coups, whereas Judah's throne remained in the hands of the Davidic dynasty based in Jerusalem.[88][d]

The Kingdom of Israel (also called Samaria, after its capital) was the more populous and economically robust of the two. It initially established its capital at Shechem, later moved to Tirzah and Mahanaim, and finally settled at Samaria. The kingdom emerged as a regional power and often clashed with its neighbors: it fought against the kingdom of Aram-Damascus to the northeast and with the Moabites and Ammonites to the east. Its ruling dynasty, however, was replaced frequently. Meanwhile, the southern Kingdom of Judah was smaller and more geographically confined, centered on Jerusalem and the Judaean Mountains. It was often overshadowed by its northern kin but had the advantage of dynastic stability under the house of David. The kingdom generally had fewer resources and a smaller army than Israel, but Jerusalem's fortified position gave it a strong defensive edge. Judah retained the First Temple in Jerusalem as the center of Yahweh worship,[89] which gave the Judahite kings and priests a unifying institution. However, high places and local shrines coexisted in Judah for much of this period, until reforms sought to centralize worship. By the mid-8th century BCE, Israel's population is estimated at 350,000, while Judah had approximately 110,000 inhabitants.[90]

As early as Israel's second king, Nadab, the ruling house was overthrown, and Baasha seized power. His son also reigned for only a short time. After a series of coup d'états, Omri (c. 880 BCE), an army commander, took power and established a more stable dynasty.[91] He was succeeded by his son Ahab, under whom Israel reached a peak of military strength and economic prosperity.[92][91] Ahab forged regional alliances, including through his marriage to Jezebel, a Phoenician princess.[93][91] Jehoshaphat of Judah, also allied with Ahab through a marriage alliance, appears to have reasserted control over Edom and attempted to revive maritime trade from Ezion-geber, though his fleet was wrecked in a storm. He also joined Israel in a joint military campaign against Moab.[94][67] After Ahab's death, the Moabites, led by Mesha, revolted and regained their independence. Jehoram of Israel, allied with Judah and Edom, attempted to reconquer Moab but was eventually forced to retreat.[95] The Mesha Stele, erected c. 840 BCE, recounts Moab's revolt against Israelite domination – it boasts of Moab throwing off the yoke of the "House of Omri" of Israel and contains what is likely the earliest non-biblical reference to the Israelite God, Yahweh.[96] The stele, discovered in Transjordan, matches the general timeframe of conflicts described in 2 Kings 3.[97]

Both Israel and Judah also had to contend with the expanding empires around them. By the 9th century BCE, the Neo-Assyrian Empire (based in Mesopotamia) began asserting its influence westward into the Levant.[98] The biblical and Assyrian records together detail how the Israelite kingdoms navigated this threat. During Ahab's time, Israel joined a regional coalition to confront the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III at the Battle of Qarqar in 853 BCE. The Kurkh Monolith, an Assyrian inscription, lists "Ahab the Israelite" among the combatants,[99] showing Israel was a significant regional player. Based on the inscription, Ahab led the second-largest army in the coalition, and commanded a chariot force larger than those of the other allies.[99][100]

Around 841 BCE, Jehu overthrew Jehoram, ending Omri's dynasty (though the Assyrians continued referring to Israel as the House of Omri). During this coup d'état, Ahaziah, king of Judah, was also killed, likely the background for the Tel Dan Inscription, in which the king of Aram boasts of killing both the kings of Israel and Judah. Jehu chose a different approach to Assyria: he paid tribute to Shalmaneser III. This event is immortalized on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser – a carved pillar from Assyria that actually depicts Jehu (or his emissary) bowing and presenting tribute to the Assyrian king. It is the only known pictorial representation of an Israelite king and confirms Israel's submission to Assyrian overlordship in the mid-9th century BCE. During this period, the usurper King Hazael of Aram Damascus successfully repelled the Assyrians, conquered parts of Israel, and brought both the kingdom of Israel and Judah, along with the Philistines, under Aramean hegemony.[101]

Remove ads

Fall of the kingdom of Israel (8th century BCE)

Summarize

Perspective

During the long reign of Jeroboam II (788–747 BCE), Israel experienced renewed prosperity and reached a territorial high point.[102] However, Assyria soon resumed its expansion into the Levant. According to the Bible, King Pekah of Israel, allied with Rezin of Aram-Damascus, invaded Judah in an attempt to replace King Ahaz with a ruler who would join a regional alliance against Assyria.[103] This prompted Ahaz to seek Assyrian assistance, leading Tiglath-Pileser III to intervene.[104] In 733–732 BCE, Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III conquered Aram-Damascus and seized much of northern Israel's territory, reducing it to a rump state. The Assyrian king captured Galilee and Gilead and the northern coastal regions, and deported their Israelite population.[105] Archaeological evidence confirms widespread destruction and significant depopulation in these areas.[105] Tiglath-Pileser III installed Hoshea as a puppet king in what remained of Israel. Hoshea, however, rebelled by allying with Egypt, which brought the wrath of Assyria.[106]

The Assyrian king Shalmaneser V launched a siege against Samaria, the capital of Israel, which lasted three years. In 722–720 BCE, the city fell to Shalmaneser or his successor Sargon II.[107] The northern Kingdom of Israel ceased to exist as an independent state[107] – its territories were divided into Assyrian provinces,[108] and a large portion of its population was deported.[106] Assyrian policy, as recorded in their annals, was to exile conquered peoples and resettle foreign populations in their place. Indeed, Assyrian records and the Bible concur that Israelites were carried off to Assyria and peoples from elsewhere were brought into Samaria. Sargon's annals record the deportation of 27,290 people from Samaria to Assyria and note the resettlement of foreign populations in the region, including settlers from Arabia.[109] According to the Bible (2 Kings 17), the deported Israelites were settled in "Halah, by the [River] Habur, [by] the River Gozan, and [among] the cities of the Medes", while foreign settlers were brought from "Babylon, and from Cuthah, and from Avva, and from Hamath and Sepharvaim."[110] The Assyrian captivity of the northern tribes gave rise to the legend of the "Lost Tribes of Israel" – although many northern Israelites likely fled to Judah.[111] Others stayed in the land and intermarried with imported groups, producing the mixed Samaritan population of later history.[112]

Remove ads

Judah between Hezekiah and Josiah (720–609 BCE)

Summarize

Perspective

Hezekiah's revolt and the Assyrian invasion

Judah, having outlasted its northern counterpart, now stood alone, though this reprieve lasted for about a century and a half.[113] For a time, Judah became a vassal of Assyria, largely spared from destruction by submitting to Assyrian rule and paying tribute.[114] The kingdom experienced a dramatic population increase, growing by two- or even threefold, likely driven by a major influx of Israelite refugees following the fall of the northern kingdom.[111] This growth was especially evident in Jerusalem, which became the largest city in the country.[111] Judah, Philistia and Edom experienced economic growth, and these regions appear to have been closely linked to Judah through shared trade networks. Some scholars attribute this prosperity to the so-called Assyrian Peace (Pax Assyriaca) and to deliberate Assyrian policies aimed at promoting regional development. Others contend that the prosperity resulted not from Assyrian efforts, but from the semi-autonomous status of these local kingdoms, which enabled them to develop their economies independently and participate in international trade. In the late 8th century, during the reign of King Hezekiah (c. 727–697 BCE[115]), Judah attempted to throw off Assyrian domination.[115] Encouraged by Assyria's temporary weakness and possibly by Egyptian diplomacy, Hezekiah joined a revolt against King Sennacherib of Assyria. Anticipating an Assyrian siege, he fortified Jerusalem's suburbs with a broad defensive wall,[116] and the underground Siloam tunnel, known for the Hebrew inscription found inside, which was used to channel Gihon spring water into the city's walls.[117] Hezekiah also sought to centralize worship by making the Jerusalem Temple the sole authorized place of religious practice, banning the use of other shrines, altars, and high places throughout the kingdom.[106]

The Assyrian response was swift and brutal: in 701 BCE, Sennacherib invaded Judah, laying waste to the countryside and capturing many fortified cities. The most famous episode of this campaign is the Siege of Lachish. Lachish was Judah's second largest city,[118] yet Sennacherib's army conquered it after a siege, an event corroborated by archaeological findings, including a siege ramp and physical evidence of intense combat.[119] The Assyrian king commemorated this victory in elaborate palace reliefs at Nineveh, which graphically depict the assault on the city, the deportation of its inhabitants, and the king enthroned as he receives their surrender.[120] These Lachish reliefs (now in the British Museum) provide an artistic record of the Assyrian invasion and confirm the biblical account of Lachish's fall (2 Kings 18:13-14, as well as references in Isaiah and 2 Chronicles).[119]

Sennacherib then turned to Jerusalem. The Bible recounts that Jerusalem was miraculously saved: an angel of the Lord struck down the Assyrian troops, or the Assyrians withdrew upon rumors of Pharaoh's approach. Assyrian records do state that Sennacherib failed to capture Jerusalem, noting only that he trapped Hezekiah in the city "like a caged bird"[115] before accepting a hefty tribute and departing. The Bible also notes Hezekiah surrendered and paid a heavy tribute. Sennacherib's emphasis on the conquest of Lachish, prominently depicted in his palace reliefs, may have served to divert attention from his failure to take Jerusalem. Thus, Jerusalem survived the 701 BCE siege, likely by paying off the invaders. Hezekiah's revolt led to Judah's renewed subjugation, widespread destruction, the loss of the fertile Shephelah, and the deportation of tens of thousands.[121][e] Still, other parts of the kingdom recovered, experiencing population growth and expanding settlement into the Negev and the Judaean Desert.[123] Above all, the survival of Jerusalem bolstered a national sense of divine favor and protection, fostering a belief in the city's invincibility—a conviction later challenged by the prophet Jeremiah.[124]

Upon Hezekiah's death, his son Manasseh succeeded him and remained a loyal Assyrian vassal throughout his reign.[125] His long rule, from around 697 to 642 BCE, saw the restoration of idolatrous practices and the rebuilding of high places, actions condemned in the Bible.[125] After Manasseh's death, his son Amon briefly ruled from around 642 to 640 BCE before being assassinated. Amon's death led to the ascension of his young son, Josiah, who began his reign at the age of eight.[125]

Josiah's reign and reforms

In the 7th century BCE, Assyria's power waned and finally collapsed with the fall of Nineveh in 612 BCE. During the power vacuum, Josiah (reigned 640–609 BCE) asserted greater independence. Josiah is renowned for his religious reforms: after an old scroll at the Jerusalem Temple,[126] he purged Judah of idolatry and local shrines, centralizing all worship at the Temple and enforcing exclusive devotion to Yahweh. Scholars link Josiah's reform (around 622 BCE) with the composition of a core of the Torah (widely believed to be an early version of the Book of Deuteronomy[127]), as part of a movement toward strict monotheism. Josiah's reign was a bright spot for Judah, as he also extended his authority into the former territory of Israel, taking advantage of Assyria's retreat. However, Judah was not the only power to exploit the Assyrian collapse—Egypt also moved in, seizing control of parts of the southern Levant. In 609 BCE, Josiah was killed at Megiddo by Pharaoh Necho II of Egypt, possibly due to suspicions of disloyalty.[128] His successors became entangled in the rivalry between Egypt and Babylon. Ultimately, Judah could not escape the fate that had befallen Israel.

Remove ads

Fall of Judah (609–587 BCE)

Summarize

Perspective

By the early 6th century BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Empire, having replaced Assyria as the dominant power in the ancient Near East, set its sights on the Levant. Babylon's policy in the region was even more ruthless than that of Assyria. In response to revolts, the Babylonians devastated rebellious territories and carried out one-way deportations to Mesopotamia. In 604 BCE, they conducted a campaign against Philistia, destroying all the Philistine cities and exiling or killing their inhabitants; within 150 years, the distinct Philistine identity ultimately disappeared.[129]

The last decades of Judah were tumultuous: one king, Jehoiakim, rebelled against Babylon; he died and was succeeded by his young son Jeconiah, who soon surrendered to Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon in 597 BCE. The Babylonians exiled Jeconiah, the royal family, and many of Judah's elites to Babylon in that year.[130] They installed Zedekiah (Jehoiachin's uncle) as a puppet king in Jerusalem. But Zedekiah too eventually rebelled, encouraged by Egyptian promises. This led Nebuchadnezzar to march on Judah once more, determined to crush it for good. In 588 BCE, Babylon laid siege to Jerusalem. The siege lasted perhaps 18 months,[131] and in 587/586 BCE the Babylonians breached Jerusalem's walls. King Zedekiah attempted to flee but was captured; his sons were killed before him and he was blinded and taken in chains to Babylon.[130] The Babylonians then burned Jerusalem to the ground, destroying the Temple of Solomon and the royal palace, and tearing down the city walls.[132] The destruction, overseen by Nebuzaradan, was deliberate and systematic—intended to eliminate Jerusalem's political and religious significance.[133]

The year 587 BCE mark the fall of Judah and the start of the Babylonian captivity. Fortified towns in the kingdom's western region, including Lachish and Azekah, were destroyed, and the settlement system throughout the kingdom experienced a widespread collapse.[134] In a letter found in Lachish from this period, the writer urgently calls for help, adding that the fire signal from Azekah is no longer visible.[135] Nebuchadnezzar's forces deported a large number of Judah's population to Babylon in several waves. Only a small portion of the population was left behind to tend the land, and they soon fell under the governance of Babylonian-appointed officials based in Mizpah in Benjamin.[136] Some fled to Egypt after Gedaliah, one of these officials, was assassinated.[137]

Remove ads

Aftermath: Babylonian captivity and the return to Zion

Summarize

Perspective

The fall of Judah in 587 BCE marks the end point of the First Temple period of Jewish history. It was an unprecedented crisis for the people of Judah: their holy city lay in ruins and the First Temple, center of their worship, was gone. The question of how this could happen despite the covenant with Yahweh led to profound soul-searching among the exiled priests, prophets, and scribes. Biblical writers interpreted the catastrophe as divine punishment for Judah's violations of the covenant, particularly the lapse into idolatry. This theological reflection during the Babylonian exile (587–538 BCE) was pivotal in shaping Judaism.

The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.[138] The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology,"[139] the idea that the god of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty would reign there forever.[140] The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community – kings, priests, scribes and prophets – to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.[141] The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah 40–55; Ezekiel; the final version of Jeremiah; the work of the hypothesized priestly source in the Pentateuch; and the final form of the history of Israel from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings.[142] Theologically, the Babylonian exiles were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world) and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.[142] Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of Hebrew identity distinct from other peoples,[143] with increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to sustain that distinction.[144]

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population[145] and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.[146] Jerusalem, destroyed but probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the settlements surrounding it, as well as the towns in the former kingdom's western borders, were all devastated as a result of the Babylonian campaign. The town of Mizpah in Benjamin in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of Yehud.[147][148] This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite (but not the bulk of the population) was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location.[149] There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at Bethel in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.[150]

Hans M. Barstad writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.[151] It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon.[152] Conversely, Avraham Faust writes that archaeological and demographic surveys show that the population of Judah was significantly reduced to barely 10% of what it had been in the time before the exile.[153] The assassination around 582 of the Babylonian governor by a disaffected member of the former royal House of David provoked a Babylonian crackdown, possibly reflected in the Book of Lamentations, but the situation seems to have soon stabilized again.[154] Nevertheless, those unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs by Samaritans, Arabs, and Ammonites.[155]

The exiles, such as the prophet Ezekiel, encouraged the community that their identity could survive without a land or Temple – through adherence to God's law and trust in His mercy. In Babylon, the Jewish exiles gathered and likely began compiling and editing their national traditions and sacred scriptures (the Torah and the historical books), solidifying their religion in written form. The exile also reinforced a trend toward full monotheism: by the end of the 6th century BCE, many Jews came to believe Yahweh was not just their national god but the only true God of all.

Later in the 6th century BCE, Babylon fell to a rising power that soon became the largest empire known at the time[156]—the Persian Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great, the first king of the Achaemenid dynasty. Cyrus issued a proclamation allowing the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild their Temple. Under Persian patronage, the Return to Zion saw some exiles return in the late 6th century BCE and rebuild the Temple, marking the beginning of the Second Temple period in Jewish history.[157]

Remove ads

Religion

Summarize

Perspective

Although the specific process by which the Israelites adopted monotheism is unknown, it is certain that the transition was a gradual one and was not totally accomplished during the First Temple period.[158][page needed] More is known about this period, as during this time writing was widespread.[159] The number of gods that the Israelites worshipped decreased, and figurative images vanished from their shrines. Yahwism, as some scholars name this belief system, is often described as a form of henotheism or monolatry. Over the same time, a folk religion continued to be practised across Israel and Judah. These practices were influenced by the polytheistic beliefs of the surrounding ethnicities, and were denounced by the prophets.[160][161][page needed][162]

In addition to the Temple in Jerusalem, there was public worship practised all over Israel and Judah in shrines and sanctuaries, outdoors, and close to city gates. In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, the kings Hezekiah and Josiah of Judah implemented a number of significant religious reforms that aimed to centre worship of the God of Israel in Jerusalem and eliminate foreign customs.[163][164][165]

Henotheism

Henotheism is the act of worshipping a single god, without denying the existence of other deities.[166] Many scholars believe that before monotheism in ancient Israel, there came a transitional period; in this transitional period many followers of the Israelite religion worshipped the god Yahweh, but did not deny the existence of other deities accepted throughout the region.[158][page needed] Henotheistic worship was not uncommon in the Ancient Near East, as many Iron Age nation states worshipped an elevated national god which was nonetheless only part of a wider pantheon; examples include Chemosh in Moab, Qos in Edom, Milkom in Ammon, and Ashur in Assyria.[167]

Canaanite religion syncretized elements from neighbouring cultures, largely from Mesopotamian religious traditions.[168] Using Canaanite religion as a base was natural due to the fact that the Canaanite culture inhabited the same region prior to the emergence of Israelite culture.[169] Israelite religion was no exception, as during the transitional period, Yahweh and El were syncretized in the Israelite pantheon.[169] El already occupied a reasonably important place in the Israelite religion. Even the name "Israel" is based on the name El, rather than Yahweh.[170][171][172] It was this initial harmonization of Israelite and Canaanite religious thought that led to Yahweh gradually absorbing several characteristics from Canaanite deities, in turn strengthening his own position as an all-powerful "One." Even still, monotheism in the region of ancient Israel and Judah did not take hold overnight, and during the intermediate stages most people are believed to have remained henotheistic.[168]

During this intermediate period of henotheism many families worshipped different gods. Religion was very much centred around the family, as opposed to the community. The region of Israel and Judah was sparsely populated during the time of Moses. As such many different areas worshipped different gods, due to social isolation.[173] It was not until later on in Israelite history that people started to worship Yahweh alone and fully convert to monotheistic values. That switch occurred with the growth of power and influence of the Israelite kingdom and its rulers. Further details of this are contained in the Iron Age Yahwism section below. Evidence from the Bible suggests that henotheism did exist: "They [the Hebrews] went and served alien gods and paid homage to them, gods of whom they had no experience and whom he [Yahweh] did not allot to them" (Deut. 29.26). Many believe that this quote demonstrates that the early Israelite kingdom followed traditions similar to ancient Mesopotamia, where each major urban centre had a supreme god. Each culture embraced their patron god but did not deny the existence of other cultures' patron gods. In Assyria, the patron god was Ashur, and in ancient Israel, it was Yahweh; however, both Israelite and Assyrian cultures recognized each other's deities during this period.[173] Some scholars have used the Bible as evidence to argue that most of the people alive during the events recounted in the Hebrew Bible, including Moses, were most likely henotheists. There are many quotes from the Hebrew Bible that are used to support this view. One such quote from Jewish tradition is the first commandment which in its entirety reads "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage: You shall have no other gods before me."[174] This quote does not deny the existence of other gods; it merely states that Jews should consider Yahweh or God the supreme god, incomparable to other supernatural beings. Some scholars attribute the concept of angels and demons found in Judaism and Christianity to the tradition of henotheism. Instead of completely getting rid of the concept of other supernatural beings, these religions changed former deities into angels and demons.[168]

Iron Age Yahwism

The religion of the Israelites of Iron Age I, like the Ancient Canaanite religion from which it evolved and other religions of the ancient Near East, was based on a cult of ancestors and worship of family gods (the "gods of the fathers").[175][176] With the emergence of the monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II the kings promoted their family god, Yahweh, as the god of the kingdom, but beyond the royal court, religion continued to be both polytheistic and family-centred.[177] The major deities were not numerous – El, Asherah, and Yahweh, with Baal as a fourth god, and perhaps Shamash (the sun) in the early period.[178] At an early stage El and Yahweh became fused and Asherah did not continue as a separate state cult,[178] although she continued to be popular at a community level until Persian times.[179]

Yahweh, the national god of both Israel and Judah, seems to have originated in Edom and Midian in southern Canaan and may have been brought to Israel by the Kenites and Midianites at an early stage.[180]

In the 10th–9th centuries BCE, the Kingdom of Israel featured a decentralized religious landscape, with local shrines found in cities like Megiddo, Tel Amal, and Ta'anach. These modest cult sites served different quarters and rural communities.[181] However, by the early 8th century BCE, these shrines disappeared, and a shift toward centralized or state-controlled worship took place. Around this time, major sanctuaries at Dan and Bethel emerged. According to the Bible, these sites were built by Jeroboam I and housed statues of young bulls.[89] Inscriptions such as the reference to "YHWH of Samaria" at Kuntillet 'Ajrud suggest that the capital also hosted a royal shrine.[182]

There is a general consensus among scholars that the first formative event in the emergence of the distinctive religion described in the Bible was triggered by the destruction of Israel by Assyria in c. 722 BCE. Refugees from the northern kingdom fled to Judah, bringing with them laws and a prophetic tradition of Yahweh. This religion was subsequently adopted by the landowners of Judah, who in 640 BCE placed the eight-year-old Josiah on the throne. Judah at this time was a vassal state of Assyria, but Assyrian power collapsed in the 630s, and around 622 Josiah and his supporters launched a bid for independence expressed as loyalty to "Yahweh alone".[183]

The Babylonian exile and Second Temple Judaism

According to the Deuteronomists, as scholars call these Judean nationalists, the treaty with Yahweh would enable Israel's god to preserve both the city and the king in return for the people's worship and obedience. The destruction of Jerusalem, its Temple, and the Davidic dynasty by Babylon in 587/586 BCE was deeply traumatic and led to revisions of the national mythos during the Babylonian exile. This revision was expressed in the Deuteronomistic history, the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings, which interpreted the Babylonian destruction as divinely-ordained punishment for the failure of Israel's kings to worship Yahweh to the exclusion of all other deities.[184]

The Second Temple period (520 BCE – 70 CE) differed in significant ways from what had gone before.[185] Strict monotheism emerged among the priests of the Temple establishment during the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, as did beliefs regarding angels and demons.[186] At this time, circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath-observance gained more significance as symbols of Jewish identity, and the institution of the synagogue became increasingly important, and most of the biblical literature, including the Torah, was substantially revised during this time.[187]

Remove ads

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

Archaeological evidence points to large-scale olive oil and wine production in the highlands.[188] Additional support comes from the Samaria ostraca—inscribed pottery shards from the 8th century BCE, likely dating to the reign of Jeroboam II. These inscriptions record administrative transactions involving olive oil and wine, along with the names of officials, and places near the Israelite capital of Samaria.[189] Archaeological evidence indicates that during the reign of Jeroboam II (786–746 BCE), the central government in Samaria initiated large-scale economic projects. Sites such as Qla', Hudash, and Kurnat Bir et-Tell appear to have functioned as royal production centers for the industrialized processing of oil and wine.[190] Israel likely became a major supplier of olive oil to neighboring powers such as Egypt and Assyria—regions whose arid climates made them less suitable for extensive olive cultivation.[191] Israel also benefited from its strategic position in regional trade, particularly through access to copper from Khirbet en-Nahas—the largest known copper production site in the southern Levant—which supplied the high demand for military equipment such as weapons and chariot fittings. However, the site declined in the 8th century BCE.[192] Israel also acted as an intermediary in the export of Egyptian horses to northern powers like Assyria. The large training facility at Megiddo and the kingdom's sizable chariot force reflect the scale of this industry.[193]

Judah's economy initially followed a traditional Mediterranean subsistence model. Under Assyrian influence, it shifted to a system where each region specialized in specific agricultural products.[194] The highlands were known for viticulture (wine production).[194] Gibeon, located in the Benjamin Plateau to the north of Jerusalem, is particularly noted for its large concentration of wine storage cellars, with 63 cellars found, which were used for aging wine.[195] The Shephelah was focused on olive oil production, alongside dry farming.[194] The Beersheba Valley for services related to Arabian trade,[194] the Judaean Desert on animal husbandry,[194] and the areas of Jericho and Ein Gedi for date and exotic plant groves.[196]

Administrative and judicial structure

Summarize

Perspective

As was customary in the ancient Near East, a king (Hebrew: מלך, romanized: melekh) ruled over the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The national god Yahweh, who selects those to rule his realm and his people, is depicted in the Hebrew Bible as having a hand in the establishment of the royal institution. In this sense, the true king is God, and the king serves as his earthly envoy and is tasked with ruling his realm. In some Psalms that appear to be related to the coronation of kings, they are referred to as "sons of Yahweh". The kings actually had to succeed one another according to a dynastic principle, even though the succession was occasionally decided through coups d'état. The coronation seemed to take place in a sacred place, and was marked by the anointing of the king who then becomes the "anointed one (māšîaḥ, the origin of the word Messiah) of Yahweh"; the end of the ritual seems marked by an acclamation by the people (or at least their representatives, the Elders), followed by a banquet.[197]

The Bible's descriptions of the lists of dignitaries from the reigns of David and Solomon show that the king is supported by a group of high dignitaries. Those include the chief of the army (Hebrew: שר הצבא, romanized: śar haṣṣābā), the great scribe (Hebrew: שר הצבא, romanized: śar haṣṣābā) who was in charge of the management of the royal chancellery, the herald (Hebrew: מזכיר, romanized: mazkîr), as well as the high priest (Hebrew: כהן הגדול, romanized: kōhēn hāggādôl) and the master of the palace (Hebrew: על הבית, סוכן, romanized: ʿal-habbayit, sōkēn), who has a function of stewardship of the household of the king at the beginning and seems to become a real prime minister of Judah during the later periods. The attributions of most of these dignitaries remain debated, as illustrated in particular by the much-discussed case of the “king's friend” mentioned under Solomon.[197][198]

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Ancient Israel, linguistically, was part of a mutually intelligible Levantine koiné language group.[199]

Music

In ancient Israel and Judah, music played a significant role in liturgies and rituals, as evidenced by several passages in the Hebrew Bible.[200] Music, both vocal and instrumental, was an integral part of worship and religious ceremonies, often used in conjunction with sacrifices and offerings. The Hebrew Bible mentions various musical instruments and practices, such as the use of trumpets in Numbers 10:1–10 during sacrifices (with Aaronite priests specifically tasked with playing the trumpets), and the association of lyres and stringed instruments with offerings in Amos 5:21–24.[201] The term "ZMR" in Hebrew, which refers to singing and making music, suggests that both vocal and instrumental music were likely combined in these rituals.[200] The use of music in religious contexts is further reflected in the book of Psalms, with several psalms providing clear evidence of music in the Jerusalem Temple, such as Psalms 66 and 68, which describe sacrificial and liturgical contexts. In Psalm 95 and 144, music is again associated with worship at the Temple, where singing and playing instruments, including lyres, would have been performed.[201]

Music in ancient Israel and Judah played a key role in ceremonial processions, blending music, movement, and a transition from the mundane to the sacred. In 1 Samuel 10:5, a "band of prophets" descends from a shrine, playing instruments like the harp (nebel), tambourine (tof), flute (ḥaliyl), and lyre (kinnôr) in a prophetic frenzy.[202] Similarly, 2 Samuel 6 describes musical processions accompanying the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem, featuring dance, shouts, and instruments such as lyres, harps, hand drums, rattles, cymbals, and trumpets (shofar), with King David dancing before the Ark.[202] Musical processions also marked significant events, like Solomon's anointing (1 Kings 1:40), where the sound was so loud it "quaked the earth," and Isaiah 30:29, where the flute accompanies movement to the Temple. Psalm 68:24–25 describes temple processions with singers, lyre players, and girls with hand drums. These processions, featuring an organized, structured musical aspect, served to reinforce communal identity, express devotion, and potentially project political power.[202]

Legacy

The religious concepts and scriptures of ancient Israel have had an enduring impact on Western civilization, surpassing its geopolitical importance during its period of existence.[203]

Ancient Israel is notable for preserving accounts of its origins, which have shaped much of the Judeo-Christian tradition and remain known throughout the Western world today.[204] The histories of Israel and Judah are known in greater detail than those of other kingdoms in the Levant, primarily due to the narratives in the Books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles, which were preserved in the Bible.[1]

See also

- Biblical archaeology

- Chronology of the Bible

- History of the ancient Levant

- History of Israel

- History of Palestine

- Jewish diaspora

- Kings of Israel and Judah

- Timeline of ancient Israel and Judah

- Timeline of Jewish history

- Timeline of the Palestine region

- Time periods in the Palestine region

- Ancient history of the Negev

Notes

- As Avraham Faust notes, this process continued into the monarchic period, with additional groups, including Canaanites from the lowlands, assimilating into the Israelite population.[38]

- Although no archaeological evidence for the temple exists due to restrictions on excavations, contemporary sites like Ain Dara in Syria, Tell Tayinat in Turkey, and Tel Motza near Jerusalem, help support its biblical description.[66]

- According to Assyrian records, 46 fortified cities and numerous rural settlements in Judah were destroyed—a figure that is widely accepted by scholars. Destruction layers attributed to this campaign have been found at nearly every major excavated site in Judah, including Lachish, Beth-Shemesh, Hebron,[clarification needed] Tel Halif, Beersheba,[clarification needed] Arad, Tel Malhata (in the Beersheba-Arad Valley of biblical Negev), Tel 'Eton, Tel Goded, Tell Beit Mirsim, Tel Batash, Khirbet Rabud, and Ramat Rahel.[122]

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads