Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Smartphone

Handheld mobile device From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

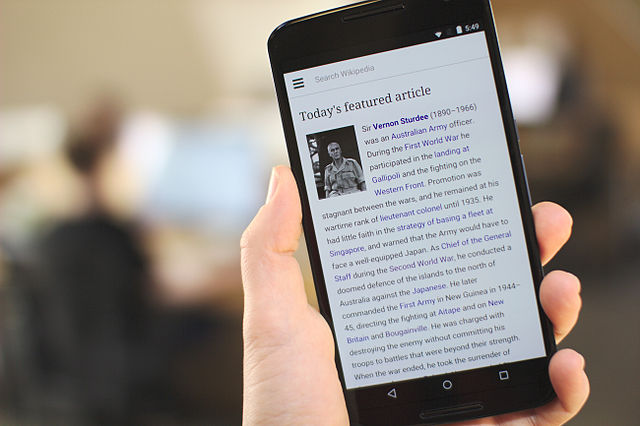

A smartphone is a mobile device that combines the functionality of a traditional mobile phone with advanced computing capabilities. It typically has a touchscreen interface, allowing users to access a wide range of applications and services, such as web browsing, email, and social media, as well as multimedia playback and streaming. Smartphones have built-in cameras, GPS navigation, and support for various communication methods, including voice calls, text messaging, and internet-based messaging apps. Smartphones are distinguished from older-design feature phones by their more advanced hardware capabilities and extensive mobile operating systems, access to the internet, business applications, mobile payments, and multimedia functionality, including music, video, gaming, radio, and television.

This page is currently being split out. Consensus to split out this page into History of smartphones has been found. You can help implement the split by following the resolution on the discussion and the splitting instructions. |

Smartphones typically feature metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chips, various sensors, and support for multiple wireless communication protocols. Examples of smartphone sensors include accelerometers, barometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers; they can be used by both pre-installed and third-party software to enhance functionality. Wireless communication standards supported by smartphones include LTE, 5G NR, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and satellite navigation. By the mid-2020s, manufacturers began integrating satellite messaging and emergency services, expanding their utility in remote areas without reliable cellular coverage. Smartphones have largely replaced personal digital assistant (PDA) devices, handheld/palm-sized PCs, portable media players (PMP),[1] point-and-shoot cameras, camcorders, and, to a lesser extent, handheld video game consoles, e-reader devices, pocket calculators, and GPS tracking units.

Following the rising popularity of the iPhone in the late 2000s, the majority of smartphones have featured thin, slate-like form factors with large, capacitive touch screens with support for multi-touch gestures rather than physical keyboards. Most modern smartphones have the ability for users to download or purchase additional applications from a centralized app store. They often have support for cloud storage and cloud synchronization, and virtual assistants. Since the early 2010s, improved hardware and faster wireless communication have bolstered the growth of the smartphone industry. As of 2014[update], over a billion smartphones are sold globally every year. In 2019 alone, 1.54 billion smartphone units were shipped worldwide.[2] As of 2020[update], 75.05 percent of the world population were smartphone users.[3]

Remove ads

History

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Needs summary of main article. (November 2025) |

Hardware

Summarize

Perspective

A typical smartphone contains a number of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chips,[4] which in turn contain billions of tiny MOS field-effect transistors (MOSFETs).[5] A typical smartphone contains the following MOS IC chips:[4]

- Application processor (CMOS system-on-a-chip)

- Flash memory (floating-gate MOS memory)

- Cellular modem (baseband RF CMOS)

- RF transceiver (RF CMOS)

- Phone camera image sensor (CMOS image sensor)

- Power management integrated circuit (power MOSFETs)

- Display driver (LCD or LED driver)

- Wireless communication chips (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, GPS receiver)

- Sound chip (audio codec and power amplifier)

- Gyroscope

- Capacitive touchscreen controller (ASIC and DSP)[4][6][7]

- RF power amplifier (LDMOS)[8][9][10]

Some are also equipped with an FM radio receiver, a hardware notification LED, and an infrared transmitter for use as remote control. A few models have additional sensors such as thermometer for measuring ambient temperature, hygrometer for humidity, and a sensor for ultraviolet ray measurement.

A few smartphones designed around specific purposes are equipped with uncommon hardware such as a projector (Samsung Beam i8520 and Samsung Galaxy Beam i8530), optical zoom lenses (Samsung Galaxy S4 Zoom and Samsung Galaxy K Zoom), thermal camera, and even PMR446 (walkie-talkie radio) transceiver.[11][12]

Central processing unit

Smartphones have central processing units (CPUs), similar to those in computers, but optimised to operate in low power environments. In smartphones, the CPU is typically integrated in a CMOS (complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor) system-on-a-chip (SoC) application processor.[4]

The performance of mobile CPU depends not only on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz)[13] but also on the memory hierarchy. Because of these challenges, the performance of mobile phone CPUs is often more appropriately given by scores derived from various standardized tests to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Buttons

Smartphones are typically equipped with a power button and volume buttons. Some pairs of volume buttons are unified. Some are equipped with a dedicated camera shutter button. Units for outdoor use may be equipped with an "SOS" emergency call and "PTT" (push-to-talk button). The presence of physical front-side buttons such as the home and navigation buttons has decreased throughout the 2010s, increasingly becoming replaced by capacitive touch sensors and simulated (on-screen) buttons.[14]

As with classic mobile phones, early smartphones such as the Samsung Omnia II were equipped with buttons for accepting and declining phone calls. Due to the advancements of functionality besides phone calls, these have increasingly been replaced by navigation buttons such as "menu" (also known as "options"), "back", and "tasks". Some early 2010s smartphones such as the HTC Desire were additionally equipped with a "Search" button (🔍) for quick access to a web search engine or apps' internal search feature.[15]

Since 2013, smartphones' home buttons started integrating fingerprint scanners, starting with the iPhone 5s and Samsung Galaxy S5.

Functions may be assigned to button combinations. For example, screenshots can usually be taken using the home and power buttons, with a short press on iOS and one-second holding Android OS, the two most popular mobile operating systems. On smartphones with no physical home button, usually the volume-down button is instead pressed with the power button. Some smartphones have a screenshot and possibly screencast shortcuts in the navigation button bar or the power button menu.[16][17][18]

Display

One of the main characteristics of smartphones is the screen. Depending on the device's design, the screen fills most or nearly all of the space on a device's front surface. Many smartphone displays have an aspect ratio of 16:9, but taller aspect ratios became more common in 2017, as well as the aim to eliminate bezels by extending the display surface to as close to the edges as possible.

Screen sizes

Screen sizes are measured in diagonal inches. Phones with screens larger than 5.2 inches are often called "phablets". Smartphones with screens over 4.5 inches in size are commonly difficult to use with only a single hand, since most thumbs cannot reach the entire screen surface; they may need to be shifted around in the hand, held in one hand and manipulated by the other, or used in place with both hands. Due to design advances, some modern smartphones with large screen sizes and "edge-to-edge" designs have compact builds that improve their ergonomics, while the shift to taller aspect ratios have resulted in phones that have larger screen sizes whilst maintaining the ergonomics associated with smaller 16:9 displays.[19][20][21]

Panel types

Liquid-crystal displays (LCDs) and organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays are the most common. Some displays are integrated with pressure-sensitive digitizers, such as those developed by Wacom and Samsung,[22] and Apple's Force Touch system. A few phones, such as the YotaPhone prototype, are equipped with a low-power electronic paper rear display, as used in e-book readers.

Alternative input methods

Some devices are equipped with additional input methods such as a stylus for higher precision input and hovering detection or a self-capacitive touch screens layer for floating finger detection. The latter has been implemented on few phones such as the Samsung Galaxy S4, Note 3, S5, Alpha, and Sony Xperia Sola, making the Galaxy Note 3 the only smartphone with both so far.

Hovering can enable preview tooltips such as on the video player's seek bar, in text messages, and quick contacts on the dial pad, as well as lock screen animations, and the simulation of a hovering mouse cursor on web sites.[23][24][25]

Some styluses support hovering as well and are equipped with a button for quick access to relevant tools such as digital post-it notes and highlighting of text and elements when dragging while pressed, resembling drag selection using a computer mouse. Some series such as the Samsung Galaxy Note series and LG G Stylus series have an integrated tray to store the stylus in.[26]

Few devices such as the iPhone 6s until iPhone Xs and Huawei Mate S are equipped with a pressure-sensitive touch screen, where the pressure may be used to simulate a gas pedal in video games, access to preview windows and shortcut menus, controlling the typing cursor, and a weight scale, the latest of which has been rejected by Apple from the App Store.[27][28]

Some early 2010s HTC smartphones such as the HTC Desire (Bravo) and HTC Legend are equipped with an optical track pad for scrolling and selection.[29]

Notification light

Many smartphones except Apple iPhones are equipped with low-power light-emitting diodes besides the screen that are able to notify the user about incoming messages, missed calls, low battery levels, and facilitate locating the mobile phone in darkness, with marginial power consumption.

To distinguish between the sources of notifications, the colour combination and blinking pattern can vary. Usually three diodes in red, green, and blue (RGB) are able to create a multitude of colour combinations.

Sensors

Smartphones are equipped with a multitude of sensors to enable system features and third-party applications.

Common sensors

Accelerometers and gyroscopes enable automatic control of screen rotation. Uses by third-party software include bubble level simulation. An ambient light sensor allows for automatic screen brightness and contrast adjustment, and an RGB sensor enables the adaption of screen colour.

Many mobile phones are also equipped with a barometer sensor to measure air pressure, such as Samsung since 2012 with the Galaxy S3, and Apple since 2014 with the iPhone 6. It allows estimating and detecting changes in altitude.

A magnetometer can act as a digital compass by measuring Earth's magnetic field.

Rare sensors

Samsung equips their flagship smartphones since the 2014 Galaxy S5 and Galaxy Note 4 with a heart rate sensor to assist in fitness-related uses and act as a shutter key for the front-facing camera.[30]

So far, only the 2013 Samsung Galaxy S4 and Note 3 are equipped with an ambient temperature sensor and a humidity sensor, and only the Note 4 with an ultraviolet radiation sensor which could warn the user about excessive exposure.[31][32]

A rear infrared laser beam for distance measurement can enable time-of-flight camera functionality with accelerated autofocus, as implemented on select LG mobile phones starting with LG G3 and LG V10.

Due to their currently rare occurrence among smartphones, not much software to utilize these sensors has been developed yet.

Storage

While eMMC (embedded multi media card) flash storage was most commonly used in mobile phones, its successor, UFS (Universal Flash Storage) with higher transfer rates emerged throughout the 2010s for upper-class devices.[33]

- Capacity

While the internal storage capacity of mobile phones has been near-stagnant during the first half of the 2010s, it has increased steeper during its second half, with Samsung for example increasing the available internal storage options of their flagship class units from 32 GB to 512 GB within only 21⁄2 years between 2016 and 2018.[34][35][36][37]

Memory cards

The space for data storage of some mobile phones can be expanded using MicroSD memory cards, whose capacity has multiplied throughout the 2010s (→ SD card § 2009–2019: SDXC). Benefits over USB on the go storage and cloud storage include offline availability and privacy, not reserving and protruding from the charging port, no connection instability or latency, no dependence on voluminous data plans, and preservation of the limited rewriting cycles of the device's permanent internal storage. Large amounts of data can be moved immediately between devices by changing memory cards, large-scale data backups can be created offline, and data can be read externally should the smartphone be inoperable.[38][39][40]

In case of technical defects which make the device unusable or unbootable as a result of liquid damage, fall damage, screen damage, bending damage, malware, or bogus system updates,[41] etc., data stored on the memory card is likely rescueable externally, while data on the inaccessible internal storage would be lost. A memory card can usually[a] immediately be re-used in a different memory-card-enabled device with no necessity for prior file transfers.

Some dual-SIM mobile phones are equipped with a hybrid slot, where one of the two slots can be occupied by either a SIM card or a memory card. Some models, typically of higher end, are equipped with three slots including one dedicated memory card slot, for simultaneous dual-SIM and memory card usage.[42]

- Physical location

The location of both SIM and memory card slots vary among devices, where they might be located accessibly behind the back cover or else behind the battery, the latter of which denies hot swapping.[43][44]

Mobile phones with non-removable rear cover typically house SIM and memory cards in a small tray on the handset's frame, ejected by inserting a needle tool into a pinhole.[45]

Some earlier mid-range phones such as the 2011 Samsung Galaxy Fit and Ace have a sideways memory card slot on the frame covered by a cap that can be opened without tool.[46]

File transfer

Originally, mass storage access was commonly enabled to computers through USB. Over time, mass storage access was removed, leaving the Media Transfer Protocol as protocol for USB file transfer, due to its non-exclusive access ability where the computer is able to access the storage without it being locked away from the mobile phone's software for the duration of the connection, and no necessity for common file system support, as communication is done through an abstraction layer.

However, unlike mass storage, Media Transfer Protocol lacks parallelism, meaning that only a single transfer can run at a time, for which other transfer requests need to wait to finish. This, for example, denies browsing photos and playing back videos from the device during an active file transfer. Some programs and devices lack support for MTP. In addition, the direct access and random access of files through MTP is not supported. Any file is wholly downloaded from the device before opened.[47]

Sound

Some audio quality enhancing features, such as Voice over LTE and HD Voice have appeared and are often available on newer smartphones. Sound quality can remain a problem due to the design of the phone, the quality of the cellular network and compression algorithms used in long-distance calls.[48][49] Audio quality can be improved using a VoIP application over Wi-Fi.[50] Cellphones have small speakers so that the user can use a speakerphone feature and talk to a person on the phone without holding it to their ear. The small speakers can also be used to listen to digital audio files of music or speech or watch videos with an audio component, without holding the phone close to the ear. However, integrated speakers may be small and of restricted sound quality to conserve space.

Some mobile phones such as the HTC One M8 and the Sony Xperia Z2 are equipped with stereophonic speakers to create spacial sound when in horizontal orientation.[51]

Audio connector

The 3.5mm headphone receptible (coll. "headphone jack") allows the immediate operation of passive headphones, as well as connection to other external auxiliary audio appliances. Among devices equipped with the connector, it is more commonly located at the bottom (charging port side) than on the top of the device.

The decline of the connector's availability among newly released mobile phones among all major vendors commenced in 2016 with its lack on the Apple iPhone 7. An adapter reserving the charging port can retrofit the plug.

Battery-powered, wireless Bluetooth headphones are an alternative. Those tend to be costlier however due to their need for internal hardware such as a Bluetooth transceiver and a battery with a charging controller, and a Bluetooth coupling is required ahead of each operation.[52]

Battery

Smartphones typically feature lithium-ion or lithium-polymer batteries due to their high energy densities.

Batteries chemically wear down as a result of repeated charging and discharging throughout ordinary usage, losing both energy capacity and output power, which results in loss of processing speeds followed by system outages.[53] Battery capacity may be reduced to 80% after few hundred recharges, and the drop in performance accelerates with time.[54][55] Some mobile phones are designed with batteries that can be interchanged upon expiration by the end user, usually by opening the back cover. While such a design had initially been used in most mobile phones, including those with touch screen that were not Apple iPhones, it has largely been usurped throughout the 2010s by permanently built-in, non-replaceable batteries; a design practice criticized for planned obsolescence.[56]

Charging

Due to limitations of electrical currents that existing USB cables' copper wires could handle, charging protocols which make use of elevated voltages such as Qualcomm Quick Charge and MediaTek Pump Express have been developed to increase the power throughput for faster charging, to maximize the usage time without restricted ergonomy and to minimize the time a device needs to be attached to a power source.

The smartphone's integrated charge controller (IC) requests the elevated voltage from a supported charger. "VOOC" by Oppo, also marketed as "dash charge", took the counter approach and increased current to cut out some heat produced from internally regulating the arriving voltage in the end device down to the battery's charging terminal voltage, but is incompatible with existing USB cables, as it requires the thicker copper wires of high-current USB cables. Later, USB Power Delivery (USB-PD) was developed with the aim to standardize the negotiation of charging parameters across devices of up to 100 Watts, but is only supported on cables with USB-C on both endings due to the connector's dedicated PD channels.[57]

While charging rates have been increasing, with 15 watts in 2014,[58] 20 Watts in 2016,[59] and 45 watts in 2018,[60] the power throughput may be throttled down significantly during operation of the device.[61][b]

Wireless charging has been widely adapted, allowing for intermittent recharging without wearing down the charging port through frequent reconnection, with Qi being the most common standard, followed by Powermat. Due to the lower efficiency of wireless power transmission, charging rates are below that of wired charging, and more heat is produced at similar charging rates.

By the end of 2017, smartphone battery life has become generally adequate;[62] however, earlier smartphone battery life was poor due to the weak batteries that could not handle the significant power requirements of the smartphones' computer systems and color screens.[63][64][65]

Smartphone users purchase additional chargers for use outside the home, at work, and in cars and by buying portable external "battery packs". External battery packs include generic models which are connected to the smartphone with a cable, and custom-made models that "piggyback" onto a smartphone's case. In 2016, Samsung had to recall millions of the Galaxy Note 7 smartphones due to an explosive battery issue.[66] For consumer convenience, wireless charging stations have been introduced in some hotels, bars, and other public spaces.[67]

Power management

A technique to minimize power consumption is the panel self-refresh, whereby the image to be shown on the display is not sent at all times from the processor to the integrated controller (IC) of the display component, but only if the information on screen is changed. The display's integrated controller instead memorizes the last screen contents and refreshes the screen by itself. This technology was introduced around 2014 and has reduced power consumption by a few hundred milliwatts.[68]

Cameras

Cameras have become standard features of smartphones. As of 2019[update] phone cameras are now a highly competitive area of differentiation between models, with advertising campaigns commonly based on a focus on the quality or capabilities of a device's main cameras.

Images are usually saved in the JPEG file format; some high-end phones since the mid-2010s also have RAW imaging capability.[69][70]

Space constraints

Typically smartphones have at least one main rear-facing camera and a lower-resolution front-facing camera for "selfies" and video chat. Owing to the limited depth available in smartphones for image sensors and optics, rear-facing cameras are often housed in a "bump" that is thicker than the rest of the phone. Since increasingly thin mobile phones have more abundant horizontal space than the depth that is necessary and used in dedicated cameras for better lenses, there is additionally a trend for phone manufacturers to include multiple cameras, with each optimized for a different purpose (telephoto, wide angle, etc.).

Viewed from back, rear cameras are commonly located at the top center or top left corner. A cornered location benefits by not requiring other hardware to be packed around the camera module while increasing ergonomy, as the lens is less likely to be covered when held horizontally.

Modern advanced smartphones have cameras with optical image stabilisation (OIS), larger sensors, bright lenses, and even optical zoom plus RAW images. HDR, "Bokeh mode" with multi lenses and multi-shot night modes are now also familiar.[71] Many new smartphone camera features are being enabled via computational photography image processing and multiple specialized lenses rather than larger sensors and lenses, due to the constrained space available inside phones that are being made as slim as possible.

Dedicated camera button

Some mobile phones such as the Samsung i8000 Omnia 2, some Nokia Lumias and some Sony Xperias are equipped with a physical camera shutter button.

Those with two pressure levels resemble the point-and-shoot intuition of dedicated compact cameras. The camera button may be used as a shortcut to quickly and ergonomically launch the camera software, as it is located more accessibly inside a pocket than the power button.

Back cover materials

Back covers of smartphones are typically made of polycarbonate, aluminium, or glass. Polycarbonate back covers may be glossy or matte, and possibly textured, like dotted on the Galaxy S5 or leathered on the Galaxy Note 3 and Note 4.

While polycarbonate back covers may be perceived as less "premium" among fashion- and trend-oriented users, its utilitarian strengths and technical benefits include durability and shock absorption, greater elasticity against permanent bending like metal, inability to shatter like glass, which facilitates designing it removable; better manufacturing cost efficiency, and no blockage of radio signals or wireless power like metal.[72][73][74][75]

Accessories

A wide range of accessories are sold for smartphones, including cases, memory cards, screen protectors, chargers, wireless power stations, USB On-The-Go adapters (for connecting USB drives and or, in some cases, a HDMI cable to an external monitor), MHL adapters, add-on batteries, power banks, headphones, combined headphone-microphones (which, for example, allow a person to privately conduct calls on the device without holding it to the ear), and Bluetooth-enabled powered speakers that enable users to listen to media from their smartphones wirelessly.

Cases range from relatively inexpensive rubber or soft plastic cases which provide moderate protection from bumps and good protection from scratches to more expensive, heavy-duty cases that combine a rubber padding with a hard outer shell. Some cases have a "book"-like form, with a cover that the user opens to use the device; when the cover is closed, it protects the screen. Some "book"-like cases have additional pockets for credit cards, thus enabling people to use them as wallets.

Accessories include products sold by the manufacturer of the smartphone and compatible products made by other manufacturers.

However, some companies, like Apple, stopped including chargers with smartphones in order to "reduce carbon footprint", etc., causing many customers to pay extra for charging adapters.

Remove ads

Software

Summarize

Perspective

Mobile operating systems

A mobile operating system (or mobile OS) is an operating system for phones, tablets, smartwatches, or other mobile devices. Globally, Android and IOS are the two most used mobile operating systems based on usage share, with the former having been the best selling OS globally on all devices since 2013.

Mobile operating systems combine features of a personal computer operating system with other features useful for mobile or handheld use; usually including, and most of the following considered essential in modern mobile systems; a touchscreen, cellular, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi Protected Access, Wi-Fi, Global Positioning System (GPS) mobile navigation, video- and single-frame picture cameras, speech recognition, voice recorder, music player, near-field communication, and infrared blaster. By Q1 2018, over 383 million smartphones were sold with 85.9 percent running Android, 14.1 percent running iOS and a negligible number of smartphones running other OSes.[76] Android alone is more popular than the popular desktop operating system Windows, and in general, smartphone use (even without tablets) exceeds desktop use. Other well-known mobile operating systems are Flyme OS and Harmony OS.

Mobile devices with mobile communications abilities (e.g., smartphones) contain two mobile operating systems—the main user-facing software platform is supplemented by a second low-level proprietary real-time operating system which operates the radio and other hardware. Research has shown that these low-level systems may contain a range of security vulnerabilities permitting malicious base stations to gain high levels of control over the mobile device.[77]

Mobile apps

A mobile app is a computer program designed to run on a mobile device, such as a smartphone. The term "app" is a short-form of the term "software application".[78]

Application stores

The introduction of Apple's App Store for the iPhone and iPod Touch in July 2008 popularized manufacturer-hosted online distribution for third-party applications (software and computer programs) focused on a single platform. There are a huge variety of apps, including video games, music products and business tools. Up until that point, smartphone application distribution depended on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms, such as GetJar, Handango, Handmark, and PocketGear. Following the success of the App Store, other smartphone manufacturers launched application stores, such as Google's Android Market (later renamed to the Google Play Store) and RIM's BlackBerry App World, Android-related app stores like Aptoide, Cafe Bazaar, F-Droid, GetJar, and Opera Mobile Store. In February 2014, 93% of mobile developers were targeting smartphones first for mobile app development.[79]

Remove ads

List of current smartphone brands

Remove ads

Sales

Summarize

Perspective

Since 1996, smartphone shipments have had positive growth. In November 2011, 27% of all photographs created were taken with camera-equipped smartphones.[80] In September 2012, a study concluded that 4 out of 5 smartphone owners use the device to shop online.[81] Global smartphone sales surpassed the sales figures for feature phones in early 2013.[82] Worldwide shipments of smartphones topped 1 billion units in 2013, up 38% from 2012's 725 million, while comprising a 55% share of the mobile phone market in 2013, up from 42% in 2012. In 2013, smartphone sales began to decline for the first time.[83][84] In Q1 2016 for the first time the shipments dropped by 3 percent year on year. The situation was caused by the maturing China market.[85] A report by NPD shows that fewer than 10% of US citizens have spent $1,000 or more on smartphones, as they are too expensive for most people, without introducing particularly innovative features, and amid Huawei, Oppo and Xiaomi introducing products with similar feature sets for lower prices.[86][87][88] In 2019, smartphone sales declined by 3.2%, the largest in smartphone history, while China and India were credited with driving most smartphone sales worldwide.[89] It is predicted that widespread adoption of 5G will help drive new smartphone sales.[90][91]

By manufacturer

In 2011, Samsung had the highest shipment market share worldwide, followed by Apple. In 2013, Samsung had 31.3% market share, a slight increase from 30.3% in 2012, while Apple was at 15.3%, a decrease from 18.7% in 2012. Huawei, LG and Lenovo were at about 5% each, significantly better than 2012 figures, while others had about 40%, the same as the previous years figure. Only Apple lost market share, although their shipment volume still increased by 12.9%; the rest had significant increases in shipment volumes of 36 to 92%.[92]

In Q1 2014, Samsung had a 31% share and Apple had 16%.[93] In Q4 2014, Apple had a 20.4% share and Samsung had 19.9%.[94] In Q2 2016, Samsung had a 22.3% share and Apple had 12.9%.[95] In Q1 2017, IDC reported that Samsung was first placed, with 80 million units, followed by Apple with 50.8 million, Huawei with 34.6 million, Oppo with 25.5 million and Vivo with 22.7 million.[96]

Samsung's mobile business is half the size of Apple's, by revenue. Apple business increased very rapidly in the years 2013 to 2017.[97] Realme, a brand owned by Oppo, is the fastest-growing phone brand worldwide since Q2 2019. In China, Huawei and Honor, a brand owned by Huawei, have 46% of market share combined and posted 66% annual growth as of 2019[update], amid growing Chinese nationalism.[98] In 2019, Samsung had a 74% market share of 5G smartphones in South Korea.[99]

In the first quarter of 2024, global smartphone shipments rose by 7.8% to 289.4 million units. Samsung, with a 20.8% market share, overtook Apple to become the leading smartphone manufacturer. Apple's smartphone shipments dropped 10%. Xiaomi secured the third spot with a 14.1% market share.[100]

By operating system

Remove ads

Use

Summarize

Perspective

Contemporary use and convergence

Some technologic devices whose markets have declined by the popularity of smartphones: (from top-left) portable media players (inc. "MP3 players"); compact digital cameras; in-car satellite navigation systems; personal digital assistants (inc. electronic organizers)

The rise in popularity of touchscreen smartphones and mobile apps distributed via app stores along with rapidly advancing network, mobile processor, and storage technologies led to a convergence where separate mobile phones, organizers, and portable media players were replaced by a smartphone as the single device most people carried.[101][102][103][104][1][105] Advances in digital camera sensors and on-device image processing software more gradually led to smartphones replacing simpler cameras for photographs and video recording.[106] The built-in GPS capabilities and mapping apps on smartphones largely replaced stand-alone satellite navigation devices, and paper maps became less common.[107] Mobile gaming on smartphones greatly grew in popularity,[108] allowing many people to use them in place of handheld game consoles, and some companies tried creating game console/phone hybrids based on phone hardware and software.[109][110] People frequently have chosen not to get fixed-line telephone service in favor of smartphones.[111][112] Music streaming apps and services have grown rapidly in popularity, serving the same use as listening to music stations on a terrestrial or satellite radio. Streaming video services are easily accessed via smartphone apps and can be used in place of watching television. People have often stopped wearing wristwatches in favor of checking the time on their smartphones, and many use the clock features on their phones in place of alarm clocks.[113] Mobile phones can also be used as a digital note taking, text editing and memorandum device whose computerization facilitates searching of entries.

Additionally, in many lesser technologically developed regions smartphones are people's first and only means of Internet access due to their portability,[114][failed verification] with personal computers being relatively uncommon outside of business use. The cameras on smartphones can be used to photograph documents and send them via email or messaging in place of using fax (facsimile) machines. Payment apps and services on smartphones allow people to make less use of wallets, purses, credit and debit cards, and cash. Mobile banking apps can allow people to deposit checks simply by photographing them, eliminating the need to take the physical check to an ATM or teller. Guide book apps can take the place of paper travel and restaurant/business guides, museum brochures, and dedicated audio guide equipment.

Mobile banking and payment

In many countries, mobile phones are used to provide mobile banking services, which may include the ability to transfer cash payments by secure SMS text message. Kenya's M-PESA mobile banking service, for example, allows customers of the mobile phone operator Safaricom to hold cash balances which are recorded on their SIM cards. Cash can be deposited or withdrawn from M-PESA accounts at Safaricom retail outlets located throughout the country and can be transferred electronically from person to person and used to pay bills to companies.

Branchless banking has been successful in South Africa and the Philippines. A pilot project in Bali was launched in 2011 by the International Finance Corporation and an Indonesian bank, Bank Mandiri.[115]

Another application of mobile banking technology is Zidisha, a US-based nonprofit micro-lending platform that allows residents of developing countries to raise small business loans from Web users worldwide. Zidisha uses mobile banking for loan disbursements and repayments, transferring funds from lenders in the United States to borrowers in rural Africa who have mobile phones and can use the Internet.[116]

Mobile payments were first trialled in Finland in 1998 when two Coca-Cola vending machines in Espoo were enabled to work with SMS payments. Eventually, the idea spread and in 1999, the Philippines launched the country's first commercial mobile payments systems with mobile operators Globe and Smart.

Some mobile phones can make mobile payments via direct mobile billing schemes, or through contactless payments if the phone and the point of sale support near-field communication (NFC).[117] Enabling contactless payments through NFC-equipped mobile phones requires the co-operation of manufacturers, network operators, and retail merchants.[118][119]

Facsimile

Some apps allows for sending and receiving facsimile (fax), over a smartphone, including facsimile data (composed of raster bi-level graphics) generated directly and digitally from document and image file formats.

Films

Films are increasingly made using smartphones and tablets, leading to the rise of dedicated film festivals for such films, including the SmartFone Flick Fest in Sydney, Australia;[120][121] Dublin Smartphone Film Festival; the International Mobil Film Festival based in San Diego; the Spanish festival Cinephone – Festival Internacional de Cine con Smartphone; the African Smartphone International Film Festival;[122] Toronto Smartphone Film Festival; New York Mobile Film Festival; and others.[123]

Remove ads

Criticism and issues

Summarize

Perspective

Social impacts

Manufacture

Cobalt and lithium are needed in order to manufacture smartphones' rechargeable batteries. Workers in cobalt and lithium mining, including children, suffer injuries, amputations, and death as the result of the hazardous working conditions and mine tunnel collapses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during artisanal mining of cobalt.[124][125] Reports indicate that thousands of artisanal lithium diggers are working in unsafe conditions, with reports of child labour and miners being buried by a mine collapse, also in Zimbabwe; and suspected corruption cases in Namibia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 2019 a lawsuit was filed against Apple and other tech companies for the use of child labor in mining cobalt;[126][127] in 2024 the court ruled that the companies were not liable.[128] Apple announced it would convert to using recycled cobalt by 2025.[129]

Use

In 2012, University of Southern California study found that unprotected adolescent sexual activity was more common among owners of smartphones.[130]

A study conducted by the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute's (RPI) Lighting Research Center (LRC) concluded that smartphones, or any backlit devices, can seriously affect sleep cycles.[131]

Some persons might become psychologically attached to smartphones, resulting in anxiety when separated from the devices.[132]

A "smombie" (a combination of "smartphone" and "zombie") is a walking person using a smartphone and not paying attention as they walk, possibly risking an accident in the process, an increasing social phenomenon.[133] The issue of slow-moving smartphone users led to the temporary creation of a "mobile lane" for walking in Chongqing, China.[134] The issue of distracted smartphone users led the city of Augsburg, Germany, to embed pedestrian traffic lights in the pavement.[135]

While driving

Mobile phone use while driving—including calling, text messaging, playing media, web browsing, gaming, using mapping apps or operating other phone features—is common but controversial, since it is widely considered dangerous due to what is known as distracted driving. Being distracted while operating a motor vehicle has been shown to increase the risk of accidents. In September 2010, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported that 995 people were killed by drivers distracted by phones. In March 2011 a US insurance company, State Farm Insurance, announced the results of a study which showed 19% of drivers surveyed accessed the Internet on a smartphone while driving.[136] Many jurisdictions prohibit the use of mobile phones while driving. In Egypt, Israel, Japan, Portugal and Singapore, both handheld and hands-free calling on a mobile phone (which uses a speakerphone) is banned. In other countries, including the UK and France, and in many US states, calling is only banned on handheld phones, while hands-free calling is permitted.

A 2011 study reported that over 90% of college students surveyed text (initiate, reply or read) while driving.[137] The scientific literature on the danger of driving while sending a text message from a mobile phone, or texting while driving, is limited. A simulation study at the University of Utah found a sixfold increase in distraction-related accidents when texting.[138] Due to the complexity of smartphones that began to grow more after, this has introduced additional difficulties for law enforcement officials when attempting to distinguish one usage from another in drivers using their devices. This is more apparent in countries which ban both handheld and hands-free usage, rather than those which ban handheld use only, as officials cannot easily tell which function of the phone is being used simply by looking at the driver. This can lead to drivers being stopped for using their device illegally for a call when, in fact, they were using the device legally, for example, when using the phone's incorporated controls for car stereo, GPS or satnav.

A 2010 study reviewed the incidence of phone use while cycling and its effects on behavior and safety.[139] In 2013 a national survey in the US reported the number of drivers who reported using their phones to access the Internet while driving had risen to nearly one of four.[140] A study conducted by the University of Vienna examined approaches for reducing inappropriate and problematic use of mobile phones, such as using phones while driving.[141]

Accidents involving a driver being distracted by being in a call on a phone have begun to be prosecuted as negligence similar to speeding. In the United Kingdom, from 27 February 2007, motorists who are caught using a handheld phone while driving will have three penalty points added to their license in addition to the fine of £60.[142] This increase was introduced to try to stem the increase in drivers ignoring the law.[143] Japan prohibits all use of phones while driving, including use of hands-free devices. New Zealand has banned handheld phone use since 1 November 2009. Many states in the United States have banned text messaging on phones while driving. Illinois became the 17th American state to enforce this law.[144] As of July 2010[update], 30 states had banned texting while driving, with Kentucky becoming the most recent addition on July 15.[145]

Public Health Law Research maintains a list of distracted driving laws in the United States. This database of laws provides a comprehensive view of the provisions of laws that restrict the use of mobile devices while driving for all 50 states and the District of Columbia between 1992, when first law was passed through December 1, 2010. The dataset contains information on 22 dichotomous, continuous or categorical variables including, for example, activities regulated (e.g., texting versus talking, hands-free versus handheld calls, web browsing, gaming), targeted populations, and exemptions.[146]

Legal

A "patent war" between Samsung and Apple started when the latter claimed that the original Galaxy S Android phone copied the interface—and possibly the hardware—of Apple's iOS for the iPhone 3GS. There was also smartphone patents licensing and litigation involving Sony Mobile, Google, Apple Inc., Samsung, Microsoft, Nokia, Motorola, HTC, Huawei and ZTE, among others. The conflict is part of the wider "patent wars" between multinational technology and software corporations. To secure and increase market share, companies granted a patent can sue to prevent competitors from using the methods the patent covers. Since the 2010s the number of lawsuits, counter-suits, and trade complaints based on patents and designs in the market for smartphones, and devices based on smartphone operating systems such as Android and iOS, has increased significantly. Initial suits, countersuits, rulings, license agreements, and other major events began in 2009 as the smartphone market stated to grow more rapidly by 2012.

Medical

With the rise in number of mobile medical apps in the market place, government regulatory agencies raised concerns on the safety of the use of such applications. These concerns were transformed into regulation initiatives worldwide with the aim of safeguarding users from untrusted medical advice.[147] According to the findings of these medical experts in recent years, excessive smartphone use in society may lead to headaches, sleep disorders and insufficient sleep, while severe smartphone addiction may lead to physical health problems, such as hunchback, muscle relaxation and uneven nutrition.[148]

Impacts on cognition and mental health

There is a debate about beneficial and detrimental impacts of smartphones or smartphone-uses on cognition and mental health.

Security

Smartphone malware is easily distributed through an insecure app store.[149][150] Often, malware is hidden in pirated versions of legitimate apps, which are then distributed through third-party app stores.[151][152] Malware risk also comes from what is known as an "update attack", where a legitimate application is later changed to include a malware component, which users then install when they are notified that the app has been updated.[153] As well, one out of three robberies in 2012 in the United States involved the theft of a mobile phone. An online petition has urged smartphone makers to install kill switches in their devices.[154] In 2014, Apple's "Find my iPhone" and Google's "Android Device Manager" can locate, disable, and wipe the data from phones that have been lost or stolen. With BlackBerry Protect in OS version 10.3.2, devices can be rendered unrecoverable to even BlackBerry's own Operating System recovery tools if incorrectly authenticated or dissociated from their account.[155]

Leaked documents from 2013 to 2016 codenamed Vault 7 detail the capabilities of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to perform electronic surveillance and cyber warfare, including the ability to compromise the operating systems of most smartphones (including iOS and Android).[156][157] In 2021, journalists and researchers reported the discovery of spyware, called Pegasus, developed and distributed by a private company which can and has been used to infect iOS and Android smartphones often—partly via use of 0-day exploits—without the need for any user-interaction or significant clues to the user and then be used to exfiltrate data, track user locations, capture film through its camera, and activate the microphone at any time.[158] Analysis of data traffic by popular smartphones running variants of Android found substantial by-default data collection and sharing with no opt-out by this pre-installed software.[159][160]

Guidelines for mobile device security were issued by NIST[161] and many other organizations. For conducting a private, in-person meeting, at least one site recommends that the user switch the smartphone off and disconnect the battery.[162]

Sleep

Using smartphones late at night can disturb sleep, due to the blue light and brightly lit screen, which affects melatonin levels and sleep cycles. In an effort to alleviate these issues, "Night Mode" functionality to change the color temperature of a screen to a warmer hue based on the time of day to reduce the amount of blue light generated became available through several apps for Android and the f.lux software for jailbroken iPhones.[163] iOS 9.3 integrated a similar, system-level feature known as "Night Shift." Several Android device manufacturers bypassed Google's initial reluctance to make Night Mode a standard feature in Android and included software for it on their hardware under varying names, before Android Oreo added it to the OS for compatible devices.[164]

It has also been theorized that for some users, addiction to use of their phones, especially before they go to bed, can result in "ego depletion." Many people also use their phones as alarm clocks, which can also lead to loss of sleep.[165][166][167][168][169]

Remove ads

Restrictions and bans

Summarize

Perspective

In some countries authorities make efforts to reduce digital device use, including smartphones among students.

- South Korea passed nationwide classroom phone ban. The law will come to effect in March 2026. Exceptions allowed for students with disabilities, emergencies and educational purposes.

- Italy, the Netherlands, and China created stronger restrictions. The policy improved the situation in Dutch schools.

- In Australia there are state-level bans. Victoria and New South Wales are introducing policies that prohibit phone use during school hours.

"There is significant scientific and medical proof that smartphone addiction has extremely harmful effects on students’ brain development and emotional growth," Cho Jung-hun, who introduced the bill in South Korea told the BBC. Not all students agree this will solve the problem. "Rather than simply taking phones away, I think the first step should be teaching students what they can do without them," said Seo Min-joon, an 18-year-old high schooler. Another student, aged 13, said that he doesn’t have time to be addicted to his phone due to an overloaded schedule.[170]

In 2024–2025 Australia and France began to advance legislation which prohibits entirely the use of social media by children under the age of 15–16.[171] In Australia the law will come into effect from 2026.[172]

Remove ads

Replacement of dedicated digital cameras

Summarize

Perspective

As the 2010s decade commenced, the sale figures of dedicated compact cameras decreased sharply since mobile phone cameras were increasingly perceived as serving as a sufficient surrogate camera.[173]

Increases in computing power in mobile phones enabled fast image processing and high-resolution filming, with 1080p Full HD being achieved in 2011 and the barrier to 2160p 4K being breached in 2013.

However, due to design and space limitations, smartphones lack several features found even on low-budget compact cameras, including a hot-swappable memory card and battery for nearly uninterrupted operation, physical buttons and knobs for focusing and capturing and zooming, a bolt thread tripod mount, a capacitor-charged xenon flash that exceeds the brightness of smartphones' LED flashlights, and an ergonomic grip for steadier holding during handheld shooting, which enables longer exposure times. Since dedicated cameras can be more spacious, they can house larger image sensors and feature optical zooming.

Since the late 2010s, smartphone manufacturers have bypassed the lack of optical zoom to a limited extent by incorporating additional rear cameras with fixed magnification levels.[174][175]

Lifespan

Summarize

Perspective

In mobile phones released since the second half of the 2010s, operational life span commonly is limited by built-in batteries which are not designed to be interchangeable. The life expectancy of batteries depends on usage intensity of the powered device, where activity (longer usage) and tasks demanding more energy expire the battery earlier.

Lithium-ion and lithium-polymer batteries, those commonly powering portable electronics, additionally wear down more from fuller charge and deeper discharge cycles, and when unused for an extended amount of time while depleted, where self-discharging may lead to a harmful depth of discharge.[176][177][178]

Manufacturers have prevented some smartphones from operating after repairs, by associating components' unique serial numbers to the device so it will refuse to operate or disable some functionality in case of a mismatch that would occur after a replacement. Locking of the serial number was first documented in 2015 on the iPhone 6, which would become inoperable from a detected replacement of the "home" button. Later, some functionality was restricted on Apple and Samsung smartphones when a battery replacement not authorized by the vendor was detected.[179][180]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- Presuming common file system support, which is usually given. Some software-specific data left over from a previous device might not be relevant on the new device.

- I.e. while the device is not in stand-by mode or charging while the main operating system is powered off.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads