Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

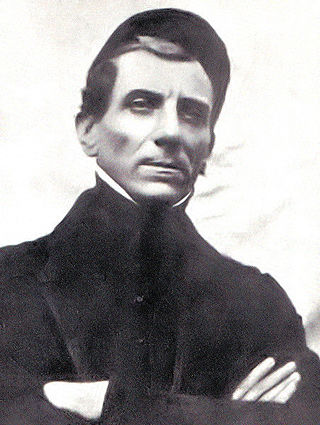

Stephan Ludwig Roth

Transylvanian-Saxon pastor (1796–1849) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Stephan Ludwig Roth (24 November 1796 – 11 May 1849) was a Transylvanian Saxon Lutheran pastor, educator, and political reformer active in the Principality of Transylvania during the first half of the 19th century. He was a prominent advocate for educational modernization based off Pestalozzian principles into Saxon schooling. He also politically campaigned for Romanians to be recognized in Saxon and the coexistence of Transylvania's multiethnic population of Hungarians, Romanians, and Transylvanian Saxons. His reformist activism brought him into conflict with the Hungarian authorities during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, and he was executed by the Hungarian revolutionary forces under the command of Lajos Kossuth in 1849. He later became a posthumous martyr amongst the Transylvanian Saxons for his progressiveness and advocating for a multiethnic empire.

Educated in Hermannstadt (Romanian: Sibiu) during his primary years, he later attended the University of Tübingen studying theology. After graduating, he worked at Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi's institute in Yverdon, before returning to Transylvania in order to spread Pestalozzi's educational and linguistic ideas. He began his career as a gymnasium professor in Mediasch and was later a Lutheran pastor in Nimesch and Meschen. During his time as pastor, he addressed a wide range of issues, which led to him becoming a political reformist. He published his ideas on guilds and promoted agricultural ideas to address rural policy. He became widely known for his 1842 publication Der Sprachkampf in Siebenbürgen, which addressed the Transylvanian Diet amongst debates over what should be the official language of Transylvania. During the Hungarian Revolution in 1848, he was appointed by the Habsburg government as the Commissioner for the 13 Saxon villages in Nagy-Küküllő, but was later arrested by Hungarian revolutionaries and executed by firing squad. Though widely commemorated later for his progressive ideals among the Transylvanian Saxons, his legacy remains complicated by present-day historians. He has been criticized more recently for his writing on Jewish people for perpetuating antisemitic stereotypes and opposing Jewish emancipation. Roth's life and work, however, continued to be studied as part of Transylvania's history, both educationally and politically, and he continues to be widely commemorated.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Stephan Ludwig Roth was born on 24 November 1796 in Mediasch in the Principality of Transylvania.[1] He was the son of Marie Elisabeth Roth (born Gunesch) and Gottlieb Roth, the rector of the Mediasch Gymnasium. He had two other siblings: Therese, who was older than Stephan, and Maria who was two years younger than him.[2] In terms of his ancestry, one part immigrated from Hamburg and the other came from Liegnitz, but most were local and were from the earliest Transylvanian Saxon settlers and came from Mediasch.[3][2] His grandfather through his paternal side was Stephan Rothmann, a shoemaker, and his maternal side was a pastoral family that had held village pastorates like Martin Fay (his great-grandfather).[4] Early on during 1803, his father was elected pastor of Kleinschelken (Romanian: Șeica Mică) to succeed Johann Gunnesch, who was his father's father-in-law, so the family moved there, with the city eventually becoming Roth's village home and the place he did his early schooling.[1]

He eventually transferred from the syntax class of Mediasch to Hermannstadt High School in May 1809, where he became part of the "Selekta" and a student inspector.[5] During his time there in Hermannstadt, he became close to his brother-in-law, Bergeileter, who held the post of principal of the Hermannstadt Gymnasium and who influenced him to improve his intellectual development.[5] In 1815, after Bergleiter died, Roth also became student librarian of the school before his examinations on 22 July 1816.[6][5] His final topic for the examinations was written in Latin over the natural order of the cosmos and disciplined thinking, which was a reflection of the nationalist spirit that was at Hermannstadt Gymnasium. He passed the matura with first class with eminence.[5]

Remove ads

Tübingen and years with Pestalozzi

Summarize

Perspective

To follow in his father's footsteps and enter the clergy, he applied for a scholarship at the Tübingen Theological Seminary, which was accepted in August 1816 by Frederick I of Württemberg as a special favor.[7] On 26 September 1816, he was informed and granted a two-year stay as a guest student at Tübingen.[5] However, he did not start at the university until 3 May 1817.[8] This was further compounded by the fact he acquired an illness in Mediasch during the winter of 1816-1817, and he finally departed for the university from 11-14 June 1817 by horse.[8]

The journey from Mediasch in June 1817 to Tübingen to 11 October 1817, took the better part of a few months, which allowed him to reflect deeply and which he later called his "educational journey".[8] He spent time in Pest and Vienna, where he reflected on Romanticism and agricultural advancements that were not seen in Transylvania at the time.[9] At this point, he considered himself a citizen of the Kingdom of Hungary, referring to himself on passports as an "Austrian native son" who liked the House of Habsburg.[9] He stated in his diaries that he believed that liberal progress could be made among the Habsburgs, despite the climate at the time, and praised the reforms of Emperor Joseph II.[9] He took a more theological approach than being supranationalist and was rationalist, which reflected rationalist Enlightenment ideas, which were formulated by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant through Blumenlese.[9] He finally arrived in Linz on 11 October, but took a detour and went by foot leading him to arrive in Tübingen on 27 November 1817, and he was finally matriculated on 1 January 1818 in the subject of theology.[8][10]

In a formative event in his life, on 19 July 1818, he met Wilhelm Stern while in Karlsruhe on vacation with friends to visit philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[8] Stern taught Latin and Greek with Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi.[8] This led him to engage in conversations during September at the university with Professor Holzmann, who was from Karlsruhe and had previously lived near Pestalozzi.[8] Not even a few months after arriving at Tübingen to study theology, he interrupted his studies again, inspired by his conversations with Holzmann, and arrived in Yverdon (Switzerland) on 1 October 1818 and was greeted by Pestalozzi and his associate Josef Schmid.[11] At this point, his wish was to become an educator of the people, spurred on by Pestalozzi's direction in Switzerland.[12] He went with Pestalozzi soon after to visit two collaborators of his, Niederer and Krüst, who had founded their own educational institution after working with Pestalozzi in Yverdon, which greatly inspired Roth.[11] On 25 December 1818 Pestalozzi formally asked Roth's father to approve a one-year stay for Stephan at the institute stating it would benefit the future of education in Transylvania, with Roth writing back a few days later stating his motivation was out of personal affection for him and a deep commitment to educational reform that Pestalozzi was developing.[11] His father quickly approved this request, and on 1 January 1819 he became a "member of the household", which meant he had received private instruction and could live in the castle at Yverdon where the institute was housed.[11] He was initially tasked with teaching Latin using Pestalozzi's method to the townspeople.[11] He was thus part of a philological team under Pestalozzi that created methods and textbooks for foreign language teaching alongside Stern, Meyer Marx, and Hirt.[13] However, he was the one who took a central position under Pestalozzi because he came from a region where multiple languages were spoken, which enabled him to understand multilingual acquisition better, like John Amos Comenius or even Pestalozzi himself.[13] During this time, he created an unpublished Latin textbook and mnemonic-based Latin teaching experiments, with both being delayed for the completion of Der Sprachunterricht, which was seen as being a potentially important contribution.[14]

In August 1819 he retreated to Bullet, and began drafting a work that Pestalozzi had commissioned him to write on teaching classical languages[11] This work, which became known as Der Sprachunterricht (Language Instruction), was developed mostly towards the end of 1819 and was translated into French and English to provide instructions on learning languages using Pestalozzi's method.[11] However, in January 1820, he fell seriously ill with a chest and stomach infection and paused work on Sprachunterricht, which eventually made Roth's father write to Pestalozzi demanding he return home.[11] Sprachunterricht itself was never finished and only survived in handwritten versions as a manuscript, unlike his colleagues' works, like Marx's method for teaching ancient language.[13] Thus, it remained unknown to anybody until 1928, when Otto Folberth printed it in Werke II with its partial translations.[15] On 5 April 1820 Pestalozzi granted Roth's leave and gave a testimonial which praised his mnemonic devices and improving language instruction and the application of these principles to Latin teaching, before Roth departed on 6 April.[16][17]

Remove ads

Return to Transylvania and Mediasch

Summarize

Perspective

He then returned home to Transylvania, staying in Freiburg where he was offered an invitation to teach at a lyceum in London which he declined, for a while before moving.[16] He made frequent stops during this journey, notably visiting Philipp Emanuel von Fellenberg at his Hofwyl School with the goal of getting his knowledge on how to recruit an agricultural student trained there to work in Transylvania.[16] He also wants to learn himself through Fellneberg the new agricultural methods.[16] He also did research on the Bell–Lancaster method, which had recently been developed, when he went to Fellenberg.[18] Fellenberg, wanting him to stay, offered him a teaching position at his school but Roth declined citing his parent's desire for him to return and went to Basel to eventually go through Karlsruhe to Tübingen.[19] Between 26 June and 30 June 1820, while staying in Tübingen, he wrote his dissertation on philosophy titled "The Nature of the State as an Educational Institution for the Human Calling", which was formally accepted on 4 July, and he was given his doctorate.[19] His main goal in writing his doctorate was to impress upon the Viennese government that he could establish a teacher training institute in Transylvania, inspired by Pestalozzi, and he declined other teaching positions again, like at Hermannstadt Gymnasium.[19] He was then instructed by the Hofkanzlei (Court Chancellery) to establish a formal plan for the school, which he presented to Count Samuel von Teleki in August, but did not receive a response for a while, so he returned home to Transylvania in September 1820.[19] The government would eventually issue a decree forbidding Roth from using his doctorate (which was foreign) in Transylvania.[20]

Finally, not receiving a response, he spoke with the superintendent of schools in Transylvania, who stated that he was against Pestalozzi's teaching methods.[19] He claimed they were only for "feeble-minded people" and that the people of Transylvania were gifted, but noted that Pestalozzi's ideas had come into fruition with the younger generation, especially in Hermannstadt (which was due to the city pastor).[19] The next few months became a difficult time in his life: the superintendent refused to acknowledge his idea because of what Roth called a biased "reviewer guild in Göttingen", and his fiancee broke off their engagement as she did not want to struggle in a foreign land with no money.[19] He tried advocating for a teacher training institute and a school journal, which eventually led him to accept a relatively modest teaching position at the Mediasch Gymnasium, which he recounted with bitterness in his diaries.[19] Since he saw no path forward with introducing anything, he instead resolved to finally get Der Sprachunterricht published and establish an educational institute in Kleinschelken.[19] Although he was listed as a teacher at this point, he was not assigned anywhere as he did not accept an assignment until his rank was formally clarified - which he was confused about.[20] To make matters worse, his bid to establish the institute in Kleinschelken dramatically failed and collapsed due to a lack of funding.[21]

In December 1822, he formally took the position at Mediasch and was assigned to teach history, periodology, and style.[22] He also began to introduce gymnastics into the curriculum, which was the first time the class had ever been part of instructions in a school in Transylvania.[23] During the year 1823 little is known about him, besides that he continued with the education of the young people, which was met with success, especially for his lectures on general and national history.[24][25] He also completed the manuscript for Sprachunterricht at this time, but struggled to get it published due to the increased hostility to Pestalozzianum ideas thanks to Pestalozzi's former assistant, Johannes Niederer, attacking the viewpoint.[26] In the classroom, he also heavily started applying Pestalozzi's pedagogical basic idea while also helping with practical training for people going into the trades and for future teachers looking to teach at grammar schools.[27] Lastly, he started his three-volume work "History of Transylvania", which was made in response to Martin Felmer's work (his work "Primae Lineae Historiae Transilvaniae" was a widely used history textbook at the time) and was intended to be the new standard for the history of Transylvania.[22][28] It covered the earliest records of its existence to 1699, which was based off an earlier manuscript from 1822.[22]

Finally, in 1828, he became vice-principal (Konrektor) of the gymnasium in Mediasch.[29] He was promoted to rector of the institution on 13 April 1831.[29] Important during his brief term as rector was that, contrary to the custom implemented at the time, all topics were discussed in Latin.[30] His school reforms during this time were also particularly notable: he was the first to include music in a Transylvanian school curriculum and proposed establishing a citizens' school and allowing rural schoolteachers to attend urban schools.[30] His introduction of music is of particular note. During his time in Yverdon, he had visited Hans Georg Nägeli's music institute, which viewed music as a form of social practice and human development.[31]

Remove ads

Consistoral conflict and appointment to first pastor

Summarize

Perspective

In March 1834, Pastor Johann Syll of the parish of Wurmloch in Mediasch was declared unfit for service and was released from duties.[32] To fill the pastorate, an electoral forum was held where Roth received the majority of the votes, 89, compared to the other 19 that Reverend Georg Friedrich Müller received.[32] However, Roth declined the position as he wished to remain rector and did not want to enter religious positions.[32] Later in 1834 he was forced on to accept a second preacher position at the Evangelical Church in Mediasch through a free election.[32] In response, he submitted an appeal, stating he did not want to vacate the rectorship to the domestic consistory, which led them to do a review of local consistory protocols and prior petitions from Roth.[32] Since they found there was a valid justification for applying the right of refusal (which had been exercised in the case of Wurmloch), they accepted his plea as they found he could not be compelled to accept the position.[32] In addition, they provided several reasons why Roth's refusal must be accepted, contrary to tradition.[32] First, Roth himself felt that the public was portraying the pastorship as an honor, but he felt like it was a punishment and a demotion.[32] Second, the community did not possess the right to compel an individual without their consent.[32] Third, that unfavorable transfers of office could only occur based on proven misconduct, and that he had been in contrast, been fully qualified in moral strength.[32] Fourth, the local custom that the people used was not a legally enforceable tradition and was not binding.[32] Therefore, the vacant position instead went to the candidate with the second-highest vote count: Lector Primus Carl Mangesius.[32] This decision was controversial in itself, which demonstrated a growing rift between schooling leadership and civic-religious authorities in Mediasch.[32]

After the community refused to comply with the decision of the domestic consistory, on 24 August, Roth was given a 15-day window to either appeal or accept the community's decision, and if an appeal was made, it would be sent to a higher ruling body of the evangelical community.[32] Roth eventually appealed, and the petition was sent to the Honorable Upper Consistory in Hermannstadt in September.[32] On 26 November, after a series of rows between the consistory and the community, the consistory agreed to fill the position of first preacher, which had been occupied by Georg Müller (who had been appointed to Baassen), with Roth as they deemed it "customary in similar cases" and that Conrector Friedrich Brecht would instead be rector of Mediasch Gymnasium.[32] Thus, in late 1834, however, he was finally forced to accept the position of first preacher of the Evangelical Church in Mediasch, which he accepted with great reluctance.[33] Some historians view this demotion was because of his efforts to remove Mediasch Gymnasium from the influence of the city's elites, which brought him into conflict with the Saxon patrician families.[33] On 2 December he was formally ordained a clergyman by Johannes Bergleiter, and he bid farewell to the gymnasium on 17 December.[30]

Through the sermons that have survived from 1835 to 1836, it can be seen that Roth was still heavily influenced by Kant's epistemology philosophy.[34] For example, his ascension sermon was almost entirely influenced by Kant's epistemological idealism, while also at the same time he expressed a supranaturalist stance (a theological stance emphasizing truth or realities that are above nature) in letters to his nephew Adolf Bergleiter.[34] Letters to Bergleiter during this time, for example, showed Roth's belief in divine revelation, so even though he was a supranationalist, he also had a rationalist undertone so his theology thus lacked a singular clarity.[34]

Remove ads

Pastoral career in Nimesch and Meschen

Summarize

Perspective

In December 1836 he resigned from the post in Mediasch and instead was elected on 21 January 1837 to the post of pastor of Nimesch (Romanian: Nemșa).[35][36] His father was previously the pastor of Nimesch 35 years earlier, in 1802, for a briefly period before taking on the pastoral role of Kleinschelken.[36] His first concern in Niemsch was to help the peasants there by studying the state of agricultural affairs and thus turn the parish's fields into a model farm for the community.[37] To this extent, he also sought to improve livestock breeding, viticulture, and fruit cultivation.[38] Since he could not establish the training center for young teachers that he had hoped for in the early 1820s, he instead resolved to set an example of teachings so that the Saxon peasants and Wallachians could learn from.[37] He did eventually establish a model farm in Rohrau, which consumed most of his savings but twice the farm buildings burned down.[39] It has also been argued by Folberth that through speech and writing during this time he sought to promote the strengthening of the Transylvanian Saxons and promote the idea of "good Germans".[40]

By 1840, Roth started taking into account Johann Gottlieb Fichte's ideas, particularly his development of German nationalism, alongside Johann Gottfried Herder's philosophy of history.[34] While also starting to embrace German nationalism, he did cultivate relations with Transylvanian Romanians.[34] During this time, he also started publishing works on farming and rural poverty, and embraced the Transylvanian Romanians by joining the "Association for the Study of Transylvania" to have an inclusive cultural development.[41] Starting in 1842, also, Pestalozzi's influence also started spreading in Hungary due to Ludwig Schedius and Teréz Brunszvik (although Roth was never acknowledged in the region for his ideas).[42] He also acquired a plot of land in Rohrau near Mediasch on the road to Hermannstadt, which included a tennant's cottage. He planned to bring a farmer from Germany to live in the cottage as a tenant and introduce rational agriculture to the townspeople through observation and examples.[42] By 1844 he introduced drawing as a subject in Mediasch, which he hoped would promote it.[43]

On 21 February 1847, after around 10 years in his post as pastor of Nimesch, he was elected pastor of Meschen (Romanian: Moşna).[44] That year he presented at a pastoral conference in Reichesdorf, where he espoused his Christian faiths.[45] He stated that the Transylvanian Saxons were divinely placed in the region to uphold Christian civilization, and that moral education was essential and that his activism was only because of his religious conviction.[45]

Remove ads

Political career

Summarize

Perspective

1841 and guilds

In 1841, he started defending the practice of the traditional guild system, which was a hotly debated issue as some wished to replace it with economic liberalism.[45] He wrote his position in the Hermannstadt newspaper Transsilvania.[45] In it, he acknowledged that the system was beginning to fall in Western Europe because of absolutist rulers and mercantilist policies and that champions of economic liberalism like Adam Smith had dissolved guilds.[45] However, he warned that the shift ended social cohesion and professional standards.[45] He also argued further that guilds in Transylvania still retained their independence and preserved craftmanship, supported community welfare, and economic stability.[45] This led to him earning some criticism, with accusations being made that he was overly nationalistic for wanting to retain the guild system, to which he responded that Saxon nationalism served the greater good and was simply a branch of his Christian faith, and was not in any way ill-intended toward other nations.[45]

In a subsequent treatise dated to 1841, he also expressed his support of a constitutional monarchy and lamented the fall of the Holy Roman Empire, which he argued fostered inner peace.[45] He stated that an idealized model of civil society could be seen in the Swiss cantons, and criticized Napoleon's centralized state model.[45] Thus, he viewed that the bourgeoisie should mediate between the states and the people, but advocated for "truly scientifically educated citizens" to advance the arts and sciences.[45]

Background to 1842

In 1842, the Transylvanian Diet in Klausenburg (Romanian: Cluj-Napoca) passed a law making Hungarian the official language, although there were some exceptions for Saxon schools and the Königsboden region, which many Saxons viewed as a clear move towards Magyarization.[46] The diet itself by this point was composed of privileged nations: Hungarians, Szeklers, and Saxons.[46] Romanians, despite being the majority, were excluded as part of the diet.[46] This was at a time of increased nationalism, which made the Hungarian elite want to restore a "historic Hungary", which included Transylvania, and Hungarians feared that their language might disappear.[46] Hungarian liberals also supported unification, stating that social reforms like the end of serfdom were associated with Magyarization, and that when the non-Magyar groups would adopt the Hungarian identity, they would have civil rights.[46] Saxons generally opposed those, fearing cultural erasure, which was a view Roth shared.[46]

1842 and Der Sprachkampf

He publicised the idea in his August 1842 work: Der Sprachkampf in Siebenbürgen, which he also supplemented with a twelve-part article in the Pest journal Der Ungar.[47] 'Der Sprachkampf was addressed implicitly to Emperor Ferdinand I, in the hopes that he would block the law's ratification (although it was passed, it still needed the emperor's approval).[46] In it, he framed the language conflict as a moral and civic crisis, arguing that the forcing of the Hungarian language as the dominant one threatened the culture of non-Magyar populations like the Transylvanian Saxons.[47] In particular, he stated that making Hungarian the administrative language was not right for Transylvania as it had limited use in the region as a cultural and bureaucratic medium.[46] Questioning why Hungarians only made up a third of the population but that they deserved more, he criticized why the Habsburgs were tolerant of the "hotheads" like Lajos Kossuth who advocated for independence.[46] He emphasized that it was a "fall from humanity" to go through with it, and that all nationalities must be respected as they were all humans.[47] Furthermore, he stated that the core of national identity was language: losing one's language meant the nation ceased to exist.[46] In the longest chapter of the work, he also deviated to talking about the Romanians, stating that he also felt empathy for their position and wished for their emancipation and inclusion as a fourth nation but did not necessarily advocate for political equality with them.[47] He considered that making Romanian as well the only official language, due to it being widely spoken, in the region would point out its ascendence over the others and its lingua franca status in the ethnical composition of the country, which showed his support for an old estate-based constitution.[46] He instead proposed the idea of making Hungarian, German, and Romanian the official languages in Transylvania.[48] These views can best be seen through quotes from Der Sprachkampf:

The gentlemen from the Diet in Klausenburg may have given birth to an official language, and now they rejoice, that the child was born.... However we have already a language of the land. It is not German, also not the Hungarian language, but the Wallachian language [Romanian language]! We may take measures and threaten as we like, that is the way it is, and not otherwise.[49]

When two people of different nationalities, who cannot speak each other's language, meet, is the Wallachian language [Romanian language] that serves as translator. No matter if one travels or goes to the market, anyone can speak Wallachian [Romanian]. Before one tries to see whether that one can speak German or that one can speak Hungarian, the discussion starts in Wallachian [Romanian].[49]

The idea in Der Sprachkampf that Roth took on reflected much of his positions, which were in line with Enlightenment thinkers like Pestalozzi and Herder.[47] He thus saw a multilingual society as essential to any society's stability, particularly the Habsburg monarchy's.[47] His essential idea was that the Hungarian aspiration for independence would lead to a Magyar-dominated state that would be ripe with minority tensions and vulnerable to foreign influence like the Ottoman Empire and more so the Russian Empire (but ultimately he stated the real threat was the principalities like Wallachia).[46] He even went so far as to call the Hungarians ungrateful, stating that the Ottomans had politically dominated the Hungarians and that Austria had "liberated Hungary" into a multiethnic empire.[46] His final note in the work was that Christianity should unite people, stating that it did not matter the denomination and that he had equal respect for them all.[46] Almost immediately after its reprinting in 1842, however, Hungarian contemporaries criticized him.[47] Hungarian publicist Zsigmond Kemény was the first to launch a major attack in Erdélyi Hiradó in December, and Miklós Wesselényi followed soon after to defend Hungarian nationalism.[50] Indeed, some scholars saw him as inconsistent as he remained loyal to an "outdated constitutional model", and also argued that Romanian was not justifiable but at the same time advocating for Hungarian, German, and Latin as the official language (which were less spoken and more regional).[46] On the opposite end, some Hungarians also defended him, particularly the then Roman Catholic Bishop of Transylvania, Miklós Kovács, who viewed the work as a defense of peaceful coexistence.[47] It was also influential to Count István Széchenyi, who delivered a speech to the academy in Pest in November 1842, which reflected many of Roth's ideas presented in the work.[50]

Subsequent career

In 1843, Roth began publishing more of his works. The first thing that he published was his work Eine Bittschrift fürs Landvolk, a pamphlet that had a specific chapter entitled "Die Zerbisselung", which was a critique of land division and the economic pressures that were put on Transylvania that drove peasants away from the field of agriculture.[51] He specifically called out intentional inheritance customs that were put in place, which he stated undermined national prosperity.[51] He also published a socio-economic treatise known as Der Geldmangel und die Verarmung in Siebenbürgen, besonders unter den Sachsen that same year, which was influential in its criticism of the feudal system, which he called for to be abolished as he argued it was incompatible with humanitarian and progressive ideals that had taken over the country.[52] The combined works led to the founding of the Transylvanian Saxon Agricultural Association in Kronstadt (Romanian: Brașov) as a way to push agriculture onto the population.[50] He also published An mein Volk! Ein Vorschlag zur Herausgabe von drei absonderlichen Zeitungen für siebenbürgisch-deutsche Landwirtschaft, Gewerbe, Schul- und Kirchensachen, in which he proposed creating more newspapers to address the issues in the community, specifically in agriculture, trades, schooling, and church matters.[53]

In 1844 the Hungarian Diet officially declared Hungarian as the sole official administrative language, which was widely influential - soon after, the Croatian Diet passed legislation replacing Latin with Croatian in all levels.[54] During this upheaval, he became personally acquainted with George Barițiu, a Romanian nationalist who published in Gazeta de Transilvania which Roth was subscribed to.[55] The agriculture association also started a newspaper during this time, in which Roth extensively wrote in for the abolition of fallow land and the introduction of crop rotation through fodder cultivation.[53]

In 1845 he started acting on his plans to advocate for German immigration to Transylvania to strengthen the Saxon element, taking a four-month leave from his post as pastor, which was taken over by Georg Paul Binder.[53] He intended to go to Württemberg to persuade progressive farmers to immigrate to Transylvania.[53] During his travels, he even met with publicist Eduard Glatz in the autumn of 1845 in Buda to discuss this proposal and getting it publicized.[47] The leading Magyar circles, however, feared that a new wave of colonization might strengthen German elements in Hungary and opposed it.[56] It took longer than expected because of his frequent detours, such as attending the General Assembly of the Gustav-Adolf Foundation in Stuttgart where he met with other bishops in the area, which is eventually published in the "Württemberg Travel Diary".[53] Eventually he set up a headquarters near Cannstatt to approach farmers in the area, and met with reformer Johannes Ronge of the dissident German Catholics.[57] Friedrich List, at the same time, took the government route and eventually approached the government of the Kingdom of Württemberg, which in turn approached the Austrian government inquiring whether Transylvania and Hungary both could receive German emigrants.[56]

This was passed to the Saxon Nationsuniversität, which gave the position that there were no areas suitable for closed settlement.[56] However, they stated there was land available for purchase at relatively low prices, as the Nationsuniversität supported the idea of a settlement.[56] They also proposed that it should now include not only farmers but also craftsmen.[56] Eventually Roth returned home in December 1845, where he made appearances at the Transylvanian Court Chancellory and was granted an audience with Archduke Louis of Austria, who at the time represented Ferdinand I of Austria in matters due to the king's severe epilepsy which prevented him from ruling.[57] He also met with Count Kolowrat, who led the Secret State Conference about the matter.[57]

By the end of March 1846, together with both of their efforts, it was reported that 914 individuals had arrived in Transylvania from Germany.[58] This was, however, met with some criticism by the emigres.[58] Many complained that despite accounts by officials, they were not satisfactorily accommodated, and some even sought shelter outside of Saxon territories, and many deaths occurred.[58] This eventually led to the Austrian legation receiving instructions not to issue visas for emigrants to the area, as they said the conditions there were not yet ripe.[58] Due to this, in the end of March Roth was summoned by the Austrian government via the Nationsuniversität to address his recruitment for peasants in Württemberg to emigrate.[57] To respond to this, he composed a written justification which he sent to the superintendent, which in the end led to no further actions.[57] This number of emigrants, even with the visas, grew to 307 families totalling 1,460 people by early June, with most of the immigrants (who came from Swabia) being accommodated.[58] By the end of 1846, 1,010 of the immigrated Swabians remained.[58]

In June of 1846 he sparked a lot of controversy with the "Mühlbach toast". He stated this during the 5th general assembly on Transylvanian regional studies and during the first general assembly of the Transylvanian Agricultural Association, both of which had been convened in Mühlbach.[57] Going off from its official agenda at the convention, he expressed that the nobility must come down to civic equality and that the future belonged to the educated serfs who would rise to civic dignity.[29] He also expressed his own desire to extend the Saxon civic constitution to all of Transylvania, showcasing his conservatism.[29][59]

The politicalness of his statement during the toast were thought to have had an effect of contributing to his conviction later on in 1849.[60] However, the immediate consequence was that the newspaper Erdélyi Hiradó immediately began a public attack against him for even suggesting social leveling, and in July the Transylvanian Court Chancellery in Vienna instructed the Gubernium in Klausenburg to hold Roth accountable for his words.[57] In response, Roth submitted a written defense to Binder which was forwarded to Vienna.[61] After the Transylvanian Court Chancellery received the defense, they revisited the case and told the Gubernium to only issue him a formal reprimand.[61]

In late 1847 he expressed his frustrations at both the Hungarian and Romanian populations.[29] He criticized the Hungarians for believing that the colonization efforts to get German immigrants to arrive to Transylvania was directed against them.[29] At the same time, he lamented about the mass immigration of Romanians to Saxon areas amid increasing dissatisfaction over the results of the immigration efforts.[29]

In March 1848 he proposed forming riflemen from Saxon hunters using private shooting societies as a militia in order to maintain peace during the revolution against the empire that had started two days before. He advocated for loyalty to the monarchy, stating that Saxons lost whenever there was upheaval due to revolution. On March 30, it was decided by the government to re-establish the Saxon militia, which had existed before.[62] However, he initially supported in the March Laws of 1848, but he returned to supporting the empire once it adopted a new constitution on 25 April that supported his stances.[63] He attended on 15 May the first ethnic Romanian gathering at Câmpia Libertății (near Blasendorf (Blaj) see Blaj Assemblies) called the Romanian People's Assembly and wrote about it in the local press under the pseudonym "Pestalozzi".[64] His articles showed a respect for the movement and highlighted Avram Iancu's contribution to the cause, supporting their right to be acknowledged as a distinct nation and civic recognition in the Transylvanian constitutional framework.[64] However, he also disapproved that some members expressed support for communism, and said it should've been condemned during the assembly.[64]

Revolution and civil war

With the outbreak of the violent clashes between Imperial and Hungarian troops in October 1848, Roth became a member of the Hermannstadt Pacification Committee.[39] He frequently condemned the Hungarian government calling it "Ultramagyarism".[65] However, in the end of October 1848, negotiations between the government and Roth were supposed to work with the Hungarians and Székelys, but collapsed, and civil war broke out in the territory.[66] Later on, on 1 November, he was appointed by the general in charge of Transylvania under the government, Anton von Puchner, as Commissioner for the 13 Saxon villages in Nagy-Küküllő (German: Groß-Kokel, Romanian: Târnava-Mare), as well as the administrator de facto of the respective county.[67] Roth was tasked by the government to annex the Königsboden villages upon their wishes due to the anarchy, and also was responsible for conscripting recruits for the Romanian legions and the militia of the "Saxon Rifle Battalion.[66][68] To try and restore order during the anarchy in the region while the villages were being annexed, Roth organized an ad hoc militia from neighboring villages and went to Gogan on a military expedition to prevent the looting of estates belonging to the Hungarian nobles that had fled.[66]

This kept some stability, so he went ahead and attempted to the 13 villages between the districts of Schäßburg (Romanian: Sighișoara) and Mediasch and began preparing for the annexation of nearby land.[66] This was controversial among the Romanians: they felt like some of the villages that were annexed were a majority Romanian, and some other opposition that Folberth conjectured was resistance even from some Saxons and of which Roth referred to in a letter dated 20 November.[68] Furthermore, the governmental committee declared that it would be a great loss for the Saxons to subjugate "brothers whom we have liberated from the Hungarians".[68] This led to Stefan Moldovan investigating the demographic composition on behalf of the government, which found the majority were Romanian and opposed any annexations (although later it was found it was needed a majority Saxons), so nevertheless he was instructed to stop Roth's plans.[68]

Puchner then appointed Roth later in November as assistant to the provisional administrator of Kőhalom County, Karl Commendo, which forced him to temporarily take post at Rupea Fortress.[66] Moldovan reached out to him during this inquiring about if the annexation had actually gone through, to which Roth responded that although he was aware the inhabitants were Romanian he had assigned the 13 villages to the jurisdictions of Schäßburg and Mediasch already.[68] He knew nothing of Moldovan's surveys, and so Moldovan responded back to the national committee that it was already too late as the annexation had gone through.[68] However, attempts at reversing the annexation were then started, while Roth, on the other hand, tried to go through with incorporating the neighboring land in a second group (the villages Belleschdorf, Bulkesch, Schönau, and Seiden were the only ones majority Saxon of the 13 in this group).[68] He rejected the Romanian argument of them having a majority of the population, and he attempted to persuade the commander that annexing would benefit the Romanians and that it was a mere ordering and that they would be treated the same.[68] However, this one never went through - this was mostly due to strong Romanian opposition and advancing forces in the civil war, which diverted Puchner and the government from the attempts.[68] Following this, his specific work as an assistant is relatively less talked about, and it is assumed that Roth was generally responsible for Saxon affairs, which Roth complained about as he stated he was too overburdened taking care of 100 Saxon villages during anarchy.[68] Despite this, Roth was not concerned about his safety after Moldovan advised him that the Saxon colleagues were fleeing as he called the Hungarians far too noble for the execution of a pastor and that the Hungarians considered the Saxons brothers.[68] Although both Commendo and Moldovan later fled in January to Mediasch, where it was safer, Roth declined to do so.[68]

With the Hungarian victories in January 1849 came the end of local government structures.[68] He subsequently left Kokelburg after Hungarian columns under János Czetz started entering the area. General Józef Bem offered the administrators amnesty, and Roth retired to Meschen at his post as pastor.[68] He subsequently fell into financial hardship: he did not receive his wages for being commissioner and later assistant, even though he formally requested compensation from Puchner. He continued to petition local magistrates, but the matter dragged on (it was never processed even after his death), and he was robbed of a lot of florins.[68]

Trial

However, in January, Lajos Kossuth set up military tribunals with László Csányi, the government commissioner of Transylvania, in which the pre-amnesty cases were trialed, backed by a parliamentary decree.[69] This was due to Bem - who protected Roth - leaving Transylvania and moving over to the Banat because of the war.[69] On 21 April 1849, on orders of Csányi, Roth was arrested in Meschen by a cavalry unit, under the following charges:

- Accepting an office under enemy's occupation

- Introducing Romanian as an official language throughout the county (a protocol written down in Romanian was presented as evidence)

- Attaching 13 villages from the county to the Saxon Seats, considered a violation of the Hungarian territory

- Robbing the Hungarian population, as leader of a Saxon and Wallachian revolt.[70]

Subsequently, he was sent to Klausenburg prison on either 27 April or 28 April.[71] Rescue attempts were made for him: some students from Schäßburg attempted to free him during a stopover when moving to Klausenburg, but Roth refused for unknown reasons.[69] In prison, he submitted a written defense to the charges: he did not deny the first three, and he believed that, because of the situation at the time, they seemed lawful and legitimate, and he believed he had acted correctly.[71] However, he rejected the final accusation and said he had plundered but instead requisitioned on orders from superiors in the government.[71] He tried evoking the amnesty under Bem, but it was rejected by the Diet and was recognized by Csányi, so it did not legally apply.[71] The defense attorney also attempted to object by saying it was a legal principle that actions that we are not questioned by criminal law prior cannot have a retroactive effect, that he had acted under moral compulsion to accept Puchner's entrustments, and that Bem had "cast a veil of oblivion" over these crimes by granting amnesty. The public prosecutor responded that the resolution of 13 February had not introduced a new penal system and that court martials had long existed, even though the defense attorney kept repeating for a full acquittal or even for a referral of the case to a regular court. However, since Roth had confirmed the allegations, the court was, by law, according to the Diet, to sentence him to death (technically, a pardon would have saved him and would have been justifiable).[71] With the pardon being the only thing that could help him, the Lutheran pastor of Klausenberg, Georg Hintz, attempted to appeal for clemency to Csányi - Csányi immediately denied it and said that Roth had worked towards the "extermination of the Hungarian nation" and also mobilized the Swabians.[71] However, his sentence was temporarily delayed from the 24 hours that it was supposed to be, likely due to the Hungarian National Assembly wanting to pass a law that allowed military tribunals to prosecute offenses committed before 13 February 1849, which was probably a reference to Roth's trial to make the actions legal.[71]

Execution

On 10 May 1849, the military tribunal formally convened. It consisted of six judges - at least three belonged to the inner circle of Erdélyi Hiradó.[69] The witness interrogation mostly rested on the military expedition in Gogan that occurred in November 1848, where he was accused of theft.[69] The witnesses stated that he protected the town from being looted by Wallachians, and said he felt duty-bound to protect the town as a loyal Austrian subject.[72] The trial lasted the following day, leading to a verbal duel taking place between the prosecutor and the defense attorney.[69] At 2 p.m., the verdict was announced, and at 5 p.m., it was announced he was sentenced to death by powder and lead (execution by gunfire).[69] His final actions were to write to his children before his death.[73] The proceedings took place at the marketplace of Klausenburg, escorted by a firing squad.[73] He was then taken to Cluj Castle Hill, to a large crowd.[74] He prayed the Lord's Prayer, and three shots were fired in a short interval, with the third being the fatal shot as it passed through his head.[74]

His body was immediately buried without a coffin in the gardens of Cluj Castle Hill, where he had been executed, as his friend Pastor Hintz could not arrange for one.[74] After the Hungarian army retreated due to the Russian Empire aiding the Habsburgs, Roth's family returned to his grave in 1850 and exhumed it.[74] They then transferred him to Mediasch on 19 April and were buried in the school garden in front of the city cemetery.[74] In May 1853, a large cast-iron obelisk was erected over his grave from donations, which bore the description honoring his memory from the Saxon people.[74]

Reactions to his execution

Hungarian officials

Just after the conclusion of Roth's trial on 11 May, Csányi was removed as Plenipotentiary Government Commissioner of Transylvania and replaced with József Szentiványi.[75] Although Csányi technically moved up governmental ranks by becoming Minister of Transport, it has been speculated that he left Transylvania as soon as the execution was carried out out of fear.[75] Also, several judges of the Klausenburg court martial, including the public prosecutor Miklós Krizbai, resigned, as evident by a letter from Countess Wass, which stated "yesterday's event made such a great impression...members of the blood court have submitted their resignations."[75]

Bem quickly issued a public declaration, which was addressed to the members of the Hungarian court-martial.[75] He was indignant after learning that his amnesty was disrespected by the courts.[75] He argued that he had not received information about the trial in order to implement a measure to prevent his execution, and that if he had, he would have prevented the execution.[75] He stated this on the grounds that courts like the one against Roth's were only used for robbers, arsonists, and the like, and wrote to Kossuth stating that Hungarian freedom meant genuine freedom and that they needed to show the people that the Austrian government was not noble.[75] Afterwards, he tried to make amends with the Roth case and had Roth's sequestered assets unsealed and given to his heirs.[75]

János Duschek, a court-martial, after hearing about Roth's death from Maager's rant, assured the Saxons that the execution left an unpleasant impression on the government as they saw the reprehensibility of the martial law, and decreed its repeal.[75] However, the repeal did not come immediately. This was mostly due to Sebő Vukovics taking over as Minister of Justice: he reduced the number of court-martials and urged public prosecutors to keep the laws established by the National Assembly in mind, eventually abolishing mixed court-martials, which muddled the process of getting the repeal actually in place.[75]

Transylvanian Saxons

Carl Maager, a Transylvanian Saxon politician who was elected to the City Council of Kronstadt and led negotiations with the leaders of the Hungarian revolution, had previously tried to contact Kossuth and other ministers to plead for saving Roth.[75] Maager, upon learning of Roth's death, lashed out at the Hungarian government for their implementation of martial law.[75] He portrayed him as defenseless and held captive, and he was slaughtered due to national enmity.[75] He further stated that any person could be hanged for public activities under the same law, saying the entire Transylvanian Saxons could be executed if such actions were taken.[75]

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Roth's first partner was Marie Schmid, who was two years older than him.[76] They first met in September 1819 when Roth was in Yverdon to work as Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi's assistant. Schmid was the sister of Pestalozzi's assistant, Josef Schmidk, and was the head of the poorhouse of Pestalozzi's in Yverdon.[76] They remained together and became engaged in the spring of 1820 in Yverdon until April 1820, when Roth was ordered to move back to Transylvania, where they then wrote back and forth in a series of letters, but ultimately their correspondence ended, and the engagement was broken off in December 1820.[76] Scholars have disputed the source for the end of their relationship: Otto Folberth stated that Marie had always been an uncertain element in the relationship, while Karl Holzträger rejected this based on Marie's stance in the letters they exchanged.[76] Holzträger rejected romantic assertions of their relationship, stating that even if Marie had broken off their engagement, and furthermore blamed Roth and asserted that he viewed love as a need for intellect.[76] Ultimately, Schmid said in her letters to him that she had broken off the relationship because she did not want to drag him down while he was struggling (at the time, financially) with the added burned of a family and bring him to complete ruin.[77]

Either way, after this heartbreak, he went to Mediasch and in June 1822 became engaged to Sophie Auner.[78] She was the daughter of the pastor of Großkopisch (Romanian: Copșa Mare), Georg Gottlieb Auner. Together, they had four children.[2] The first of them was Maria Elisabeth Sophie (born 1826), who married merchant Michael Gottlieb Rosenauer, and they together they had many children together until her death in 1913 - most descendants of Roth come from her.[2] They also had two other children: Stephan Ludwig Heinrich (born 1824), who died in 1841, and was a shop servant in Nimesch from emaciation, and Friederike Josepha (born 1829) who died in 1841 from emaciation also.[2] In 1831, Auner died from tuberculosis in Mediasch.[2] He later remarried his second wife, Karoline Henter, on 18 February 1837. Henter was the daughter of Bogeschdorf (Romanian: Băgaciu) pastor Andreas Henter.[2] Together, they had five children.[2] One emigrated out of Transylvania, Stephan Andreas (born 1838), to the United States with his wife Christine Ruder from Vienna but died in a traffic accident in 1907 in Cleveland.[2] His other children were Johanna Karolina (born 1839), who married merchant Josef Traugott Theil, and another was Stephan Gottlieb (born 1847), who was a cadet in the 17th Jägerbataillon but died from tuberculosis.[2] The last two were Regina Karolina Theresia (born 1845) who died at the age of ten and Maria Karolina (born 1847) who married Heinrich Siegmund, a pharmacist, and later captain Bernhard Sykan.[2] He also had one adopted child who he started taking care of in October 1848 after finding them in the in a forest near Meschen.[39]

After his death, he asked the state for continued support for his foster child.[39] On 26 August 1849 this was granted by Emperor Franz Joseph I, who granted all of Roth's underage children an annual educational allowance of 200 Gulden which was to be paid until they reached the age of 24.[79]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Roth has become a "martyr" among the Transylvanian Saxons.[80] He has been considered one of the most progressive figures in advocating for social justice and equality, and was called a "man ahead of his time".[81] Throughout out his life, however, he was respected but also controversial - his ideas on official languages were known, but more of his reformist ideas went unheard of or failed.[80] However, his death in 1849 changed people's viewpoints on him, to where he became a martyr and Saxon contemporaries viewed him as a celebrated hero.[80] For example, Andreas Gräser, the rector of the Mediasch Gymnasium by 1852, portrayed him as a genuine German spirit.[80]

At the same time, some Marxist historians and authors have criticized the depiction of Roth by people like Folberth, who they accused of fascist tendencies.[80] For example, Heinz Stănescu stated that Folberth, in his biographies, was not objective and portrayed him in a "falsified, historically sentimental" light.[80] Historians like Martin Wellmann later agreed with this in studies, opining that there was no biography that was objective and met standards.[80] Thus, subsequent biographies attempted to change this, like Michael Kroner's biography attempted to humanize Roth and remove any mythical glorification so that he was no longer a saint.[80] Nevertheless, he has continued to be presented as an "outstanding figure" among Transylvanian Saxons for advocating for a peaceful coexistence with different languages to introduce equality, like with the Romanians.[80]

For decades after his death, it was tradition in Mediasch to hold a ceremonial procession from the Mediasch Gymnasium across the marketplace to the Student Garden where his grave is in order to commemorate Roth.[80] On 24 April 2007 the Poșta Română, the national postal services in Romania, published a special edition of stamps intro circulation that depicted German personalities in Romania.[82] Roth was illustrated on a stamp with a face value of 3.90 Lei.[82]

Views on Jews

Authors like Kroner later attempted to analyze his views on Jewish people to see if he truly advocated for a peaceful coexistence.[80] Kroner found that Roth was often deeply contradictory between theological ideas and antisemitic prejudice that was present in Austria-Hungary.[80] Roth expressed admiration for the ancient Hebrews, who he viewed as industrious, and praised the Hebrew language and Old Testament for shaping human morality and intellectual development.[80] He wanted people to study Hebrew as a root language, and said the biblical Israelites were part of the "oriental heights" from which education and spiritual progress first emerged in the world.[80]

On the other hand, Roth viewed contemporary Jews in Austria-Hungary in a demeaning manner.[80] He often invoked antisemitic tropes, describing them as "bloodsuckers", "money-creatures", and "parasitic plants", accusing them of economic exploitation and deceit.[80] He opposed any Jewish emancipation, saying they lacked civic virtue and they should be excluded from Austrian citizenship until they proved themselves.[80] He specifically criticized the Talmud as promoting anti-Christian views.[80] He often generalized his views from isolated experiences, thus leading him to believe that economic reforms should restrict Jewish participation.[80]

These views on ambivalence mirrored people Roth admired, like Herder and Pestalozzi, who would praise the Hebrew past of Jews but would be antisemitic in the present.[80] Kroner used this to argue that Roth was not truly consistently tolerant like Folberth believed, but was contradictory in advocating for reforms while at the same time perpetuating prejudices that he reformed against.[80]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads