Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

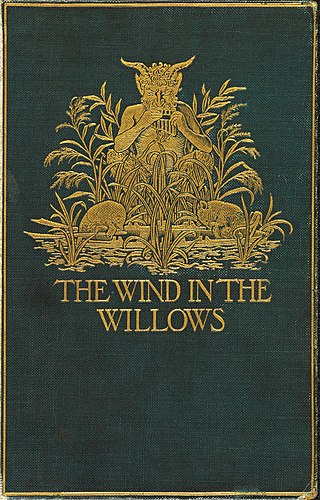

The Wind in the Willows

1908 children's novel by Kenneth Grahame From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Wind in the Willows is a children's novel by the British novelist Kenneth Grahame, first published in 1908. It details the story of Mole, Ratty, and Badger as they try to help Mr. Toad, after he becomes obsessed with motorcars and gets into trouble. It also details short stories about them that are disconnected from the main narrative. The novel was based on bedtime stories Grahame told his son Alastair. It has been adapted numerous times for both stage and screen.

The Wind in the Willows received negative reviews upon its initial release, but it has since become a classic of British literature. It was listed at No. 16 in the BBC's survey The Big Read[2] and has been adapted multiple times in different media.

Remove ads

Background

In 1899, at age 40, Kenneth Grahame married Elspeth Thomson, the daughter of Robert William Thomson. The next year they had their only child, a boy named Alastair (nicknamed "Mouse"). He was born premature, blind in one eye, and plagued by health problems throughout his life.[3] When Alastair was about four years old, Grahame would tell him bedtime stories, some of which were about a toad, and on his frequent boating holidays without his family he would write further tales of Toad, Mole, Ratty, and Badger in letters to Alastair.[4]

In 1908, Grahame took early retirement from his position as secretary of the Bank of England. He moved with his wife and son to an old farmhouse in Blewbury, Berkshire. There, he used the bedtime stories he had told Alastair as a basis for the manuscript of The Wind in the Willows.

Remove ads

Plot summary

Summarize

Perspective

With the arrival of spring and fine weather outside, the good-natured Mole loses patience with spring cleaning, exclaiming, "Hang spring cleaning!" He leaves behind his underground home and comes up at the bank of the river, which he has never seen before. Here he meets Rat, a water vole, who takes Mole for a ride in his rowing boat. They get along well and spend many more days boating, with "Ratty" teaching Mole the ways of the river, with the two friends living together in Ratty's riverside home.

One summer day, Rat and Mole disembark near the grand Toad Hall and pay a visit to Toad. Toad is rich, jovial, friendly, and kindhearted, but sometimes arrogant and rash; he regularly becomes obsessed with current fads, only to abandon them abruptly. His current craze is his horse-drawn caravan. When a passing car scares his horse and causes the caravan to overturn into a ditch, Toad's craze for caravan travel is immediately replaced by an obsession with motorcars.

Mole goes to the Wild Wood on a snowy winter's day, hoping to meet the elusive but virtuous and wise Badger. He gets lost in the woods, succumbs to fright, and hides among the sheltering roots of a tree. Rat finds him as snow begins to fall in earnest. Attempting to find their way home, Mole barks his shin on the boot scraper on Badger's doorstep. Badger welcomes Rat and Mole to his large, cosy underground home, providing them with hot food, dry clothes, and reassuring conversation. Badger learns from his visitors that Toad has crashed seven cars, has been in hospital three times, and has spent a fortune on fines.

With the arrival of spring, the three of them put Toad under house arrest with themselves as the guards, but Toad pretends to be sick and tricks Ratty to leave so he can escape. Badger and Mole continue to live in Toad Hall in the hope that Toad may return. Toad orders lunch at The Red Lion Inn and then sees a motorcar pull into the courtyard. Taking the car, he drives it recklessly, is caught by the police, and is sent to prison for 20 years (most of which is for "gross impertinence" to his captors).

In prison, Toad gains the sympathy of the gaoler's daughter, who helps him to escape disguised as a washerwoman. After a long series of misadventures, he returns to the hole of the Water Rat. Rat hauls Toad inside and informs him that Toad Hall has been taken over by weasels, stoats, and ferrets from the Wild Wood, who have driven out Mole and Badger. Armed to the teeth, Badger, Rat, Mole, and Toad enter through the tunnel and pounce upon the unsuspecting Wild-Wooders who are holding a celebratory party. Having driven away the intruders, Toad holds a banquet to mark his return, during which he behaves both quietly and humbly. He makes up for his earlier excesses by seeking out and compensating those he has wronged, and the four friends live happily ever after.

In addition to the main narrative, the book contains several independent short stories featuring Rat and Mole, such as an encounter with the wild god Pan while searching for Otter's son Portly, and Ratty's meeting with a Sea Rat. These appear for the most part between the chapters chronicling Toad's adventures, and they are often omitted from adaptations of the story, as well as some abridged versions.

Remove ads

Main characters

- Mole: known as "Moley" to his friends. An independent, timid, genial, thoughtful, home-loving animal and the first character introduced in the story. Discontent with spring cleaning in his secluded home, he ventures into the outside world. Initially intimidated by the hectic lifestyle of the riverbank, he eventually adapts with the support of his new friend Rat. He has a spontaneous intelligence moment with his trickery against the Wild Wooders before the battle to retake Toad Hall.

- Rat: known as "Ratty" to his friends (though actually a water vole), he is astute, charming, and affable. He enjoys a life of leisure; when not spending time on the river, he composes doggerel. Ratty loves the river and befriends Mole. He can be very unsettled about subjects and endeavours outside his preferred routine, but is persistently loyal and does the right thing when needed, such as when he risks his life to save Mole in the Wild Wood, and helps rid Toad Hall of the unruly weasels. Ratty is the free and easy sort, as well as a dreamer, and he has a poetic thought process, finding deeper meaning, beauty, and intensity in situations others may see through more practical eyes.

- Mr. Toad: known as "Toady" to his friends, the wealthy scion of Toad Hall who inherited his wealth from his late father. He is gregarious and well-meaning, but as a fixated control freak, he is sometimes inclined to boast lavishly and make outrageous outbursts when held back by another character, regardless of their intentions with him. He is prone to obsessions (such as punting, houseboats, and horse-drawn caravans) but gets dissatisfied with each of these activities and drops them fairly quickly, finally settling on motorcars. His motoring craze degenerates into a sort of addiction that lands him in the hospital a few times, subjects him to expensive fines for his unlawfully erratic driving, and eventually gets him imprisoned for theft, dangerous-driving, and severe impertinence to the police. Two chapters of the book chronicle his daring escape from prison.

- Mr. Badger: a firm but considerate animal, Badger embodies the "wise hermit" figure. A friend of Toad's deceased father, he is strict with the immature Toad, yet hopes that his good qualities will prevail through his shortcomings. He lives in a vast underground sett, part of which incorporates the remains of a buried Roman settlement. A fearless and powerful fighter, Badger helps clear the Wild-Wooders from Toad Hall with his large stick.

Remove ads

Supporting characters

- Otter and Portly: a good friend of Ratty with a stereotypical "Cockney costermonger" character, Otter is confident, respected and headstrong. Portly is his young son.

- The weasels, ferrets, and stoats: the story's main antagonists. They plot to take over Toad Hall. Although they are unnamed, the leader is referred to as "Chief Weasel".

- Pan: a gentle and wise god of the wild who makes a single, anomalous appearance in Chapter 7, "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn", when he helps Portly and looks after him until Ratty and Mole find him.

- The Gaoler's Daughter: the only major human character, she embodies the youth perspective toward the situation faced by Toad whilst he is incarcerated in prison; a "good, kind, clever girl", she helps Toad escape.

- The Wayfarer: a vagabond seafaring rat, who also makes a single appearance in Chapter 9, "Wayfarers All". Ratty briefly contemplates accompanying him on his adventures, before Mole convinces him otherwise.

- Squirrels and rabbits, who are generally good-natured (although rabbits are described as "a mixed lot").

- Inhabitants of the Wild Wood: weasels, stoats, and foxes who are described by Ratty as "All-right in a way but well, you can't really trust them".

- The Engine Driver: An unnamed man who drives a steam engine on the railway. When Toad is in his washerwoman disguise and unable to purchase a ticket to the station nearest to Toad Hall, the driver takes sympathy upon hearing Toad's false tale of woe and gives him a free ride on the engine, with the promise that he wash a few of the driver's clothes. During the journey, the driver becomes aware that Toad isn't really a washerwoman, upon sighting a single engine that is following them and carrying officials of the law who try to get his attention. Once Toad confesses his actions, the driver thinks he should turn Toad in, but not having a fancy for motorcars nor being ordered about on his own engine, he allows Toad to escape after the train has passed through a tunnel.

- The Barge Woman: An unnamed woman who owns a barge. Like the Engine Driver, she is briefly fooled by Toad's washerwoman disguise and offers Toad a ride, with the promise that he wash her clothes. Upon realising that he is actually a toad, she throws him off the barge and into a river flowing by. Toad gets infuriated and decides to take revenge by leaving the river and stealing the horse of the barge woman.

Remove ads

Editions

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

The original publication of the book was plain text, with a frontispiece illustrated by Graham Robertson, but many illustrated, comic, and annotated versions have been published over the years. Notable illustrators include Paul Bransom (1913), Nancy Barnhart (1922), Wyndham Payne (1927), Ernest H. Shepard (1931), Arthur Rackham (1940), Richard Cuffari (1966), Tasha Tudor (1966), Michael Hague (1980), Scott McKowen (2005), and Robert Ingpen (2007).

- The 1927 edition illustrated by Wyndham Payne was noted for its use of a distinctive colour of yellow, described by some cultural commentators as canary yellow.

- The most popular illustrations are probably by E. H. Shepard, originally published in 1931, and believed to be authorised as Grahame was pleased with the initial sketches, although he did not live to see the completed work.[5]

- The Wind in the Willows was the last work illustrated by Arthur Rackham. The book with his illustrations was issued posthumously in a limited edition by the Folio Society with 16 colour plates in 1940 in the US. It was not issued with the Rackham illustrations in the UK until 1950.

- The Folio Society 2006 edition featured 85 illustrations, 35 in colour, by Charles van Sandwyk. A fancier centenary edition was produced two years later.

- Michel Plessix created a Wind in the Willows watercolour comic album series, which helped to introduce the stories to France. They have been translated into English by Cinebook Ltd.

- Patrick Benson re-illustrated the story in 1994 and HarperCollins published it in 1994 together with the William Horwood sequels The Willows in Winter, Toad Triumphant and The Willows and Beyond. It was published in the US in 1995 by St. Martin's Press.

- Inga Moore's edition, abridged and illustrated by her, is arranged so that a featured line of the text also serves as a caption to a picture.

- Barnes & Noble Classics featured an introduction by Gardner McFall in 2007. New York, ISBN 978-1-59308-265-9

- Egmont Press produced a 100th Anniversary paperback edition, with Shepard's illustrations, in 2008. ISBN 978-1-4052-3730-7

- Belknap Press, a division of Harvard University Press, published Seth Lerer's annotated edition in 2009.[6]

- W. W. Norton published Annie Gauger's and Brian Jacques's annotated edition in 2009.[7]

- Jamie Hendry Productions published a special edition of the novel in 2015 and donated it to schools in Plymouth and Salford to celebrate the World Premiere of the musical version of The Wind in the Willows by Julian Fellowes, George Stiles, and Anthony Drewe.[8]

- IDW Publishing published an illustrated edition of the novel in 2016.[9] The hardcover novel features illustrations from Eisner Award-winning artist David Petersen, who is best known for creating and drawing the comic series Mouse Guard.

- Simon & Schuster published a lavishly illustrated edition in 2017.[10] Illustrator Sebastian Meschenmoser created more than 100 expressive watercolour vignettes and a dozen lush oil paintings.

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

A number of publishers rejected the manuscript. It was published in the UK by Methuen and Co., and later in the US by Scribner. The critics, who were hoping for a third volume in the style of Grahame's earlier works, The Golden Age and Dream Days, generally gave negative reviews.[4] The public loved it, however, and within a few years it sold in such numbers that many reprints were required, with 100 editions reached in Britain alone by 1951.[11] In 1909, then US President Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Grahame to tell that he had "read it and reread it, and have come to accept the characters as old friends".[12]

In The Enchanted Places, Christopher Robin Milne wrote of The Wind in the Willows:

A book that we all greatly loved and admired and read aloud or alone, over and over and over: The Wind in the Willows. This book is, in a way, two separate books put into one. There are, on the one hand, those chapters concerned with the adventures of Toad; and on the other hand there are those chapters that explore human emotions – the emotions of fear, nostalgia, awe, wanderlust. My mother was drawn to the second group, of which "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" was her favourite, read to me again and again with always, towards the end, the catch in the voice and the long pause to find her handkerchief and blow her nose. My father, on his side, was so captivated by the first group that he turned these chapters into the children's play, Toad of Toad Hall. In this play one emotion only is allowed to creep in: nostalgia.

Remove ads

Adaptations

Summarize

Perspective

Stage

- Toad of Toad Hall by A. A. Milne, produced in 1929 when the novel was in its 31st printing.

- Wind in the Willows, a 1985 Tony-nominated Broadway musical with book by Jane Iredale, lyrics by Roger McGough and music by William P. Perry, starring Nathan Lane.

- The Wind in the Willows by Alan Bennett, which premiered in December 1990 at the National Theatre in London.

- Mr. Toad's Mad Adventures by Vera Morris.

- Wind in the Willows (UK National Tour) by Ian Billings.

- The Wind in the Willows,[13] two stage adaptations – a full musical adaptation and a small-scale, shorter, stage play version – by David Gooderson.

- The Wind in the Willows,[14] a musical theatre adaption by Scot Copeland and Paul Carrol Binkley.

- The Wind in the Willows[15] by George Stiles, Anthony Drewe and Julian Fellowes which opened at Theatre Royal Plymouth in October 2016 before playing at The Lowry, Salford, and then later at the London Palladium in the West End.

- The Wind in the Willows (musical play) adapted by Michael Whitmore for Quantum Theatre, music by Gideon Escott and lyrics by Jessica Selous that toured in 2019.

- The Wind in the Willows,[16] opera for children in two acts by Elena Kats-Chernin (music) and Jens Luckwaldt (libretto, with English translation by Benjamin Gordon), commissioned by Staatstheater Kassel and had its world premiere on 2 July 2021.

- The Wind in the Willows (a musical in two acts), adapted by Andrew Gordon for Olympia Family Theater, music by Bruce Whitney, lyrics by Daven Tillinghast, Andrew Gordon, and Bruce Whitney that premiered in 2012.[17]

- The Wind in the Willows (for actors, singers and orchestra), adapted by Neil Brand, commissioned by BBC Radio 3 and BBC Radio 4, world premiere BBC Maida Vale Studios 16 February 2013 - with BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Timothy Brock.

- The Wind in the Willows, a musical theatre adaption by Douglas Post.[18][19]

Theatrical films

- The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, a 1949 animated adaptation produced by Walt Disney Productions for RKO Radio Pictures, narrated by Basil Rathbone. One half of the animated feature was based on the unrelated short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" by Washington Irving.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1996 live-action film written and directed by Terry Jones starring Steve Coogan as Mole, Eric Idle as Rat, and Jones as Mr. Toad.

Television

- Toad of Toad Hall, the first live action telecast of the novel. Adapted by Michael Barry for BBC Television and transmitted live in 1946. The film featured (in alphabetical order) Julia Braddock as Marigold, Kenneth More as Mr. Badger, Jack Newmark as Mole, Andrew Osborn as Water Rat, Jon Pertwee as the Judge, Alan Reid as Mr. Toad, John Thomas and Victor Woolf as Alfred the Horse, Madoline Thomas as Mother, and an uncredited Pat Pleasanse as various rats, weasels, and mice.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1969 TV series adaptation of the story produced by Anglia Television, told by still illustrations by artist John Worsley. The story was adapted, produced, and narrated by Paul Honeyman and directed by John Salway.

- The Reluctant Dragon & Mr. Toad Show, a 1970–1971 TV series produced by Rankin/Bass Productions and animated overseas by Mushi Production in Tokyo, Japan, based on both The Reluctant Dragon and The Wind in the Willows.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1983 animated TV film version with stop-motion animated puppets, featuring the voice of David Jason and produced by Cosgrove Hall Films.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1984–1990 TV series following the 1983 film, using the same sets and characters in mostly original stories, but also including some chapters from the book that were omitted in the film, notably "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". The cast included David Jason (reprising his role from the film), Sir Michael Hordern, Peter Sallis, Richard Pearson, and Ian Carmichael. This series then had another TV movie made entitled A Tale of Two Toads and then a spin off series entitled Oh, Mr. Toad.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1985/1987 animated musical TV film version for television, produced by Rankin/Bass Productions with animation by Wang Film Productions (also known as Cuckoo's Nest Studios) in Taiwan. This version was very faithful to the book and featured a number of original songs, including the title, "Wind in the Willows", performed by folk singer Judy Collins. Voice actors included Eddie Bracken as Mole, Jose Ferrer as Badger, Roddy McDowell as Ratty, and Charles Nelson Reilly as Toad.[20]

- Wind in the Willows, a 1988 animated made-for-TV film by Burbank Films Australia and adapted by Leonard Lee.

- Willow Town, a 1993 Japanese anime series later dubbed in English in Australia.

- The Adventures of Mole, first part of a 1995 animated made-for-TV film produced by Martin Gates with a cast including Hugh Laurie as Toad, Richard Briers as Ratty, Peter Davison as Mole, and Paul Eddington as Badger. This part ends shortly after the visit to Badger at his home. The story is continued in Mole's Christmas and The Adventures of Toad.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1995 animated TV film adaptation narrated by Vanessa Redgrave (in the live action scenes), with a cast led by Michael Palin and Alan Bennett as Ratty and Mole, Rik Mayall as Toad, and Michael Gambon as Badger; followed by an adaptation of The Willows in Winter produced by the now defunct TVC (Television Cartoons) in London.[21]

- The Wind in the Willows, a 1999 Czech animated TV series.

- The Wind in the Willows, another live-action TV film in 2006, with Lee Ingleby as Mole, Mark Gatiss as Ratty, Matt Lucas as Toad, Bob Hoskins as Badger, and also featuring Imelda Staunton, Anna Maxwell Martin, Mary Walsh, and Michael Murphy.

- Toad & Friends, a 2023 animated comedy series, is based on The Wind in the Willows with Adrian Edmondson as Toad, Seána Kerslake as Hedge the Hedgehog, Rish Shah as Mole and Reuben Joseph as Ratty.

- The Wind in the Willows, a 2025 four-part told adaptation of the story produced by school's TV company Time Capsule Video

Unproduced

- In 2003, Guillermo del Toro was working on an adaptation for Disney. It was to mix live action with CG animation, and the director explained why he had to leave the helm. "It was a beautiful book, and then I went to meet with the executives and they said, 'Could you give Toad a skateboard and make him say, "radical dude" things?' and that's when I said, 'It's been a pleasure ...'"[22]

Web series

- In 2014, Classic Alice took the titular character on a six episode reimagining of The Wind in the Willows. Reid Cox played Toad, and Kate Hackett and Tony Noto served as loose Badger, Ratty, and Mole characters.

Radio

The BBC has broadcast a number of radio productions of the story. Dramatisations include:

- Eight episodes from 4 to 14 April 1955, BBC Home Service. With Richard Goolden, Frank Duncan, Olaf Pooley, and Mary O'Farrell.

- Episodes from 27 September to 15 November 1965, BBC Home Service, with Leonard Maguire, David Steuart, and Douglas Murchie.

- Single 90 minute play, dramatised by A.A. Milne under the name Toad of Toad Hall, on 21 April 1973, BBC Radio 4, with Derek Smith, Bernard Cribbins, Richard Goolden, and Cyril Luckham.

- Six episodes from 28 April to 9 June 1983, BBC Schools Radio, Living Language series. With Paul Darrow as Badger.

- Six episodes, dramatised by John Scotney, from 13 February to 20 March 1994, BBC Radio 5, with Martin Jarvis, Timothy Bateson, Willie Rushton, George Baker, and Dinsdale Landen.

- Single two-hour play, dramatised by Alan Bennett, on 27 August 1994, BBC Radio 4.

Abridged readings:

- A ten-part reading by Alan Bennett from 31 July to 11 August 1989 on BBC Radio 4.

- A twelve-part reading by Bernard Cribbins from 22 December 1983 to 6 January 1984 on an unknown BBC channel.

- A three-hour reading by June Whitfield, Nigel Anthony, James Saxon and Nigel Lambert, available on a Puffin audiobook published in 1996.

Other presentation formats:

- Kenneth Williams did a version of the book for radio.

- In 1986, Oxford University Press published a musical entertainment, The Wind in the Willows, by composer John Rutter and lyricist David Grant. It features a narrator, five soloists, a SATB chorus, and instrumentalists. The piece, which runs slightly over one-half hour, highlights the story of Toad and was first performed by The King's Singers in 1981.[23][24]

- In 2002, Paul Oakenfold produced a trance soundtrack for the story that aired on the Galaxy FM show Urban Soundtracks. The soundtrack blended classic stories with a mixture of dance and contemporary music.

- In 2013, Andrew Gordon produced a full-cast audio adaptation of his stage play, available on Audible and on CD.[25]

Sequels and alternative versions

- Jan Needle's Wild Wood was published in 1981 with illustrations by William Rushton (ISBN 0-233-97346-X). It is a re-telling of the story of The Wind in the Willows from the point of view of the working-class inhabitants of the Wild Wood. For them, money is short and employment hard to find. They have a very different perspective on the wealthy, easy, careless lifestyle of Toad and his friends.

- Dixon Scott's A Fresh Wind in the Willows, illustrated by Jonathon Coudrille, was published by Heinemann/Quixote in England in 1983 and Dell Yearling in the United States in 1987.

- William Horwood created several sequels to The Wind in the Willows: The Willows in Winter, Toad Triumphant, The Willows and Beyond, and The Willows at Christmas (1999). These books include some of the same incidents as Scott's sequel, including a climax in which Toad steals a Bleriot monoplane.

- Jacqueline Kelly's sequel Return to the Willows was published in 2012.

- Kij Johnson published The River Bank in 2017. If Wild Wood reimagined Grahame's work through a shift of class, Johnson's work may be said to do the same thing through shift of gender.

- Daniel Mallory Ortberg included the story "Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Mr. Toad," which blends Wind in the Willows with the Donald Barthelme short story "Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby," in his 2018 collection The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror. In Ortberg's retelling, Toad's friends are abusive and use the guise of "rescuing" their friend to justify violence and manipulation.

- Frederick Thurber's In the Wake of the Willows was published in 2019. It is the New World version of the original, recounting the adventures of the same set of characters and their children, who lived on a coastal estuary in southern New England.

- Dina Gregory released an all-female adaptation on Audible in 2020. The story sticks very closely to the original, but with Lady Toad, Mistress Badger, Miss Water Rat, and Mrs Mole.[26]

- Peter Darne's and Leon Mitchell's The Wind in the Willows was published as an audiobook in 2024 with original illustrations by Peter Darnes. The illustrations are based on the early artistic style of Peter Darnes drawings from his childhood, using soft pastel pencils. The adaptation is an infusion of telling the story of The Wind in the Willows with the classic texts and characters, supported by newly produced music and soundscapes to give the audiobook a modern take. The audiobook was produced by British award-winning director and BAFTA member Leon Mitchell.

Remove ads

Awards

- Mr. Toad was voted Number 38 among the 100 Best Characters in Fiction Since 1900 by Book magazine in their March/April 2002 issue.[27]

Inspiration

Mapledurham House in Oxfordshire was an inspiration for Toad Hall,[28] although Hardwick House and Fawley Court also make this claim.[29]

The village of Lerryn in Cornwall claims to be the setting for the book.[30]

Simon Winchester suggested that the character of Ratty was based on Frederick Furnivall, a keen oarsman and acquaintance of Grahame.[31] The writer Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, a friend of Grahame who enjoyed boating, has also been suggested as the inspiration for Ratty.[12]

The Scotsman[32] and Oban Times[33] suggested The Wind in the Willows was inspired by the Crinan Canal, because Grahame spent some of his childhood in Ardrishaig.

There is a proposal that the idea for the story arose when its author saw a water vole beside the River Pang in Berkshire, southern England. A 29 hectare extension to the nature reserve at Moor Copse, near Tidmarsh Berkshire, was acquired in January 2007 by the Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust.[34]

Peter Ackroyd, in his book Thames: Sacred River, asserts that "Quarry Wood, bordering on the river [Thames] at Cookham Dean, is the original of [the] 'Wild Wood'..."[35]

In popular culture

Music

- The first album by the psychedelic rock group Pink Floyd, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), was named by the founding member Syd Barrett after Chapter 7 of The Wind in the Willows. However, the songs on the album are not directly related to the contents of the book.

- Chapter 7 was the basis for the name and lyrics of "Piper at the Gates of Dawn", a song by the Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison from his 1997 album The Healing Game.

- The song "The Wicker Man" by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden includes the lyric "the piper at the gates of dawn is calling you his way". The song is otherwise unrelated to The Wind in the Willows, instead taking inspiration from the 1973 film with which it shares a title.

- The British extreme metal band Cradle of Filth released a special edition of its album Thornography called Harder, Darker, Faster: Thornography Deluxe; on the song "Snake-Eyed and the Venomous", a pun is made in the lyrics "... all vipers at the gates of dawn" referring to Chapter 7 of the book.

- The song "Power Flower" on Stevie Wonder's 1979 album Stevie Wonder's Journey Through "The Secret Life of Plants", co-written with Michael Sembello, mentions "the piper at the gates of dawning".

- In 1991, Tower of Power included an instrumental entitled "Mr. Toad's Wild Ride" on the album Monster on a Leash.

- Wind in the Willows is a fantasy for flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon, narrated by John Frith (2007).

- The Dutch composer Johan de Meij wrote a music piece for concert band in four movements, named after and based on The Wind in the Willows.

- The Edinburgh-based record label Song, by Toad Records takes its name from a passage in The Wind in the Willows.

- English composer John Rutter wrote a setting of The Wind in the Willows for narrator, SATB chorus, and chamber orchestra.

- The American post-hardcore band La Dispute adapted the first chapter of the book into the song "Seven" on their EP Here, Hear II.

- The song "Sweet Amarillo", written by Donna Weiss and performed by Old Crow Medicine Show, mentions The Wind in the Willows.

Adventure rides

- Mr. Toad's Wild Ride is the name of a ride at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and a former attraction at Disney's Magic Kingdom in Orlando, Florida, inspired by Toad's motorcar adventure. It is the only ride with an alternative Latin title, given as the inscription on Toad's Hall: Toadi Acceleratio Semper Absurda ("Toad's Ever-Absurd Acceleration"). After the removal of the ride from the Magic Kingdom, a statue of Toad was added to the cemetery outside the Haunted Mansion attraction in the same park.

- The Toad Hall Restaurant inspired by Toad's home is located in Fantasyland at Disneyland Paris and serves traditional English fish and chips, tea and cake.

Other

- In 2016, the historian Adrian Greenwood was tortured and murdered in his home by a thief intent on finding a rare 1908 first edition print of which he was in possession. The book was later recovered as part of the criminal investigation. The crime was the subject of a Channel 4 documentary entitled Catching a Killer: The Wind in the Willows Murder.[36][37]

- In The Simpsons episode "Lisa Gets an 'A'", Lisa neglects to complete her Wind in the Willows reading homework and subsequently has to cheat on a pop-quiz.

- In the Rugrats episode "The Santa Experience, Chaz mentions that he had the lead role in a Wind in the Willows play in school when they were kids. Drew remarks that Chaz just played a tree.

- In Alan Moore's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Mr. Toad appear in one of the issues, although this version of Toad is a creation of Dr. Moreau.[38]

- In a series 2 episode of Downton Abbey, the Dowager Countess learns that her granddaughter, Lady Edith Crowley, has volunteered to drive a tractor for a local farmer during the war, to which the Dowager Countess says, "You're a lady. Not Toad of Toad Hall!"[39]

- Two notable gay bars in San Francisco's Castro District were named Toad Hall. The first was open from 1971 to 1979, and the second from 2008 to the present day.

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads