Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Turin King List

Ancient Egyptian manuscript From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Turin King List, also known as the Turin Royal Canon, is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus thought to date from the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC), now in the Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum)[1] in Turin. The papyrus is the most extensive list available of kings compiled by the ancient Egyptians, and is the basis for most Egyptian chronology before the reign of Ramesses II. The list records a total of 278 kings, but only 165 names have survived (sometimes only partially).

Remove ads

Creation and use

Summarize

Perspective

The papyrus is believed to date from the reign of Ramesses II, during the middle of the New Kingdom, or the 19th Dynasty. The beginning and ending of the list are now lost; there is no introduction, and the list does not continue after the 19th Dynasty. The composition may thus have occurred at any subsequent time, from the reign of Ramesses II to as late as the 20th Dynasty.

The papyrus lists the names of rulers, the lengths of reigns in years, with months and days for some kings. In some cases they are grouped together by family, which corresponds approximately to the dynasties of Manetho's book. The list includes the names of ephemeral rulers or those ruling small territories that may be unmentioned in other sources.

The list also is believed to contain kings from the 15th Dynasty, the Hyksos who ruled Lower Egypt and the River Nile delta. The Hyksos rulers do not have cartouches (enclosing borders which indicate the name of a king), and a hieroglyphic sign is added to indicate that they were foreigners, although typically on King Lists foreign rulers are not listed.

The papyrus was originally a tax roll, but on its back is written a list of rulers of Egypt – including mythical kings such as gods, demi-gods, and spirits, as well as human kings. That the back of an older papyrus was used may indicate that the list was not of great formal importance to the writer, although the primary function of the list is thought to have been as an administrative aid. As such, the papyrus is less likely to be biased against certain rulers and is believed to include all the kings of Egypt known to its writers up to the 19th or 20th Dynasty.

Remove ads

Discovery and reconstruction

Summarize

Perspective

Circumstances surrounding the discovery of the papyrus

The circumstances surrounding the discovery of the papyrus are no longer known, and there are many unclear points surrounding them; the archaeological context is lost. All we know is that the Italian traveler Bernardino Drovetti bought it c. 1818 in Thebes, Egypt. Purchased in Livorno in 1820, it was shipped to Genoa by sea and then overland to Turin in 1824. The 19th-century Egyptologist Gaston Maspero believed that Drovetti had unintentionally mutilated the papyrus during his journey.[2]

It was acquired in 1824 by the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy and was designated Papyrus Number 1874. When the box in which it had been transported to Italy was unpacked, the list had disintegrated into small fragments. Jean-Francois Champollion, examining it, could recognize only some of the larger fragments containing royal names, and produced a drawing of what he could decipher. A reconstruction of the list was created to better understand it and to aid in research.

Research and processing

The Saxon researcher Gustav Seyffarth re-examined the fragments, some only one square centimeter in size, and made a more complete reconstruction of the papyrus based only on the papyrus fibers, as he could not yet determine the meaning of the hieratic characters. Subsequent work on the fragments was done by the Munich Egyptologist Jens Peter Lauth, which largely confirmed the Seyffarth reconstruction. Giulio Farina, the director of the Museo Egizio from 1928 to 1946 published his analysis and examination of this document in 1938 in a book called The Restored Papyrus of the Kings or Turin Canon; here, he proposed a new placement of some fragments, gave the hieroglyphic transcription of the hieratic text, the translation and an extensive historical-chronological commentary.[3]

In 1997, prominent Egyptologist Kim Ryholt published a new and better interpretation of the list in his book The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. Egyptologist Donald Redford has also studied the papyrus and has noted that although many of the list's names correspond to monuments and other documents, there are some discrepancies and not all of the names correspond, questioning the absolute reliability of the document for pre-Ramesses II chronology.

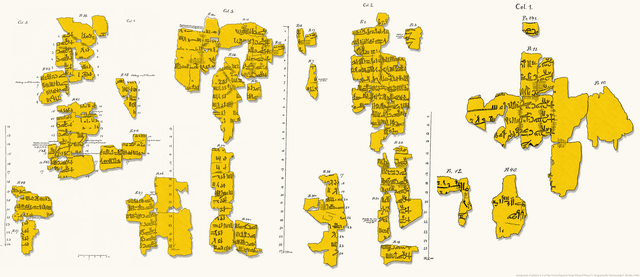

Despite attempts at reconstruction, approximately 50% of the papyrus remains missing. This papyrus as presently constituted is 1.7 m long and 0.41 m wide, broken into over 160 fragments. In 2009, previously unpublished fragments were discovered in the storage room of the Egyptian Museum of Turin, in good condition.[4] The fragments were found after studying a 1959 study by archaeologist Alan Gardiner. In his writing, Gardiner suggested that there were fragments in the museum that had not been used by scholars in reconstructing the document.[5]

The name Hudjefa, found twice in the papyrus, is now known to have been used by the royal scribes of the Ramesside era during the 19th Dynasty, when the scribes compiled king lists such as the Saqqara King List and the royal canon of Turin and the name of a deceased pharaoh was unreadable, damaged, or completely erased.

Remove ads

Contents of the papyrus

Summarize

Perspective

The papyrus is divided into eleven columns, distributed as follows. The names and positions of several kings are still being disputed, since the list is so badly damaged. Pharaohs that are known have the damaged part of the inscribed name in parentheses, if the damage part is known.

- Column 1 – Gods of Ancient Egypt

- Column 2 – Gods of Ancient Egypt, spirits and mythical kings

- Column 3 – Rows 1–10 (Spirits and mythical kings), Rows 11–25 (Dynasties 1–2)

- Column 4 – Rows 1–25 (Dynasties 2–5)

- Column 5 – Rows 1–26 (Dynasties 6–8/9/10)

- Column 6 – Rows 12–25 (Dynasties 11–12)

- Column 7 – Rows 1–2 (Dynasties 12–13)

- Column 8 – Rows 1–23 (Dynasty 13)

- Column 9 – Rows 1–27 (Dynasty 13–14)

- Column 10 – Rows 1–30 (Dynasty 14)

- Column 11 – Rows 1–30 (Dynasties 14–17)

It's possible that a twelfth column once existed that contained Dynasties 18–19/20, but that section has since been lost.

The following are the names written on the papyrus, omitting the years.

Remove ads

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian papyri

- Lists of ancient kings

- List of pharaohs

- Palermo Stone (An older fragmented king list)

- Abydos King List (A contemporary king list)

References

Sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads