Pertempuran Kursk

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

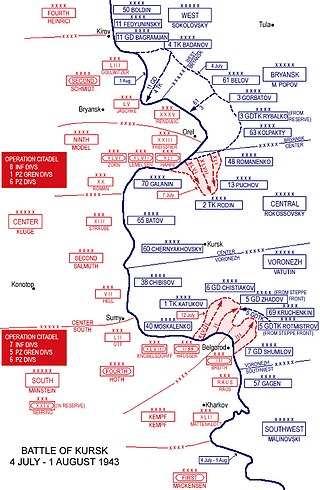

Pertempuran Kursk adalah satu pertembungan Perang Dunia Kedua antara tentera Jerman dan Soviet di Barisan Timur berhampiran Kursk (450km dari barat daya Moscow) di Soviet Union semasa bulan Julai dan Ogos 1943. Penyerangan Jerman telah diberi nama kod Operasi Citadel (Jerman: Unternehmen Zitadelle) dan membawa kepada salah satu pertempuran kereta kebal terbesar dalam sejarah, iaitu Pertempuran Prokhorovka. Penyerangan Jerman telah dibalas dengan dua penyerangan balas Soviet, Operasi Polkovodets Rumyantsev (Rusia: Полководец Румянцев) dan Operasi Kutuzov (Rusia: Кутузов). Bagi pihak Jerman, pertempuran itu menggambarkan penyerangan strategik terakhir yang mereka dapat lancarkan di Barisan Timur. Bagi pihak Soviet, kemenangan tersebut memberi Tentera Merah inisiatif strategik untuk keseluruhan perang.

Pihak Jerman berharap dapat melemahkan potensi penyerangan Soviet untuk musim panas tahun 1943 dengan memutuskan sejumlah besar tentera yang mereka jangkakan akan berada di dalam kawasan sesusuh Kursk.[33] Kawasan sesusuh atau kawasan berunjur Kursk itu berkeluasan 250 kilometer (160 bt) daripada utara ke selatan dan 160 kilometer (99 bt) daripada timur ke barat.[34] Dengan menghapuskan sesusuh Kursk, pihak Jerman juga akan memendekkan garisan pertahanan mereka, membantutkan penguasaan Soviet di sektor kritikal (yang mana dapat melegakan beberapa beban yang ditanggung oleh pihak Jerman dan memberi mereka masa untuk berkumpul semula dan merancang penyerangan lain terhadap pihak Soviet) dan mendapatkan semula inisiatif daripada pihak Soviet.[35] Rancangan ini membayangkan satu pelitupan oleh sepasang gerakan kacip yang memecah masuk melalui rusuk utara dan selatan kawasan sesusuh itu.[36] Diktator Jerman Adolf Hitler percaya kemenangan disini akan menaikkan semula kekuatan Jerman dan memperbaharui prestijnya dengan sekutunya, yang telah menimbang untuk menarik diri dari peperangan.[37] Ia juga berharap ramai tawanan Soviet dapat ditangkap supaya dapat digunakan sebagai hamba abdi dalam industri persenjataan Jerman.[35]

Pihak risikan Soviet telah mengetahui niat Jerman, sesetengahnya disediakan oleh bahagian perisikan dan pemintas Tunny. Beberapa bulan sebelum serangan akan berlaku di genting sesusuh Kursk, pihak Soviet membina satu pertahanan secara mendalam yang direka untuk memusnahkan penggempur panzer Jerman.[38] Pihak Jerman melambatkan penyerangan itu, sambil mereka cuba membina tenteranya dan menunggu senjata baru, terutamanya kereta kebal baru Panther dan juga sejumlah besar kereta kebal berat Tiger.[39][40][41] Ini memberikan Tentera Merah masa untuk membina berturut-turut lingkaran pertahanan jauh kedalam. Persiapan pertahanan termasuklah kawasan periuk api, perkubuan, zon tembak artileri dan kubu anti-kereta kebal, yang mana memanjang kira-kira 300 km (190 bt) ke dalam.[42] Formasi mudah gerak Soviet telah dikeluarkan dari kawasan sesusuh itu dan sebuah pasukan besar simpanan telah dibentuk untuk penyerangan balas strategik.[43]

Pertempuran Kursk adalah pertama kali dalam Perang Dunia Kedua yang serangan strategik Jerman telah dihentikan sebelum ia boleh memecah masuk pertahanan musuh dan menembusi kedalaman strategiknya.[44][45] Kedalaman maksimum kemaraan Jerman ialah 8–12 kilometer (5.0–7.5 bt) di utara dan 35 kilometer (22 bt) di selatan.[46] Walaupun Tentera Darat Soviet telah berjaya dalam penyerangan musim sejuk sebelum ini, penyerangan balas mereka selepas serangan Jerman di Kursk merupakan kejayaan strategik penyerangan musim panas pertama mereka dalam peperangan.[47]

Remove ads

Nota

- "With the final destruction of German forces at Kharkov, the Battle of Kursk came to an end. Having won the strategic initiative, the Red Army advanced along a 2,000 kilometer (1,200 bt)* front." (Taylor & Kulish 1974, halaman 171).

- The breakdown as shown in Bergström (2007, pp. 127–128) is as follows: 1,030 aircraft of 2nd Air Army and 611 of 17th Air Army on the southern sector (Voronezh Front), and 1,151 on the northern sector (Central Front).(Bergström 2007, halaman 21).

- The breakdown as shown in Zetterling & Frankson (2000, p. 20) is as follows: 1,050 aircraft of 16th Air Army (Central Front), 881 of 2nd Air Army (Voronezh Front), 735 of 17th Air Army (only as a secondary support for Voronezh Front), 563 of the 5th Air Army (Steppe Front) and 320 of Long Range Bomber Command.

- The breakdown as shown in Frieser (2007, p. 154) is as follows: 9,063 KIA, 43,159 WIA and 1,960 MIA.

- The breakdown as shown in Krivosheev (1997, pp. 132–134) is as follows: Kursk-defence: 177,847; Orel-counter: 429,890; Belgorod-counter: 255,566.

- The breakdown as shown in Krivosheev (1997, p. 262) is as follows: Kursk-defence; 1,614. Orel-counter; 2,586. Belgorod-counter; 1,864.

- Some military historians consider Operation Citadel, or at least the southern pincer, as envisioning a blitzkrieg attack or state it was intended as such. Some of the historians taking this view are: Lloyd Clark (Clark 2012, halaman 187), Roger Moorhouse (Moorhouse 2011, halaman 342), Mary Kathryn Barbier (Barbier 2002, halaman 10), David Glantz (Glantz 1986, halaman 24; Glantz & House 2004, halaman 63, 78, 149, 269, 272, 280), Jonathan House (Glantz & House 2004, halaman 63, 78, 149, 269, 272, 280), Hedley Paul Willmott (Willmott 1990, halaman 300), and others. Also, Niklas Zetterling and Anders Frankson specifically considered only the southern pincer as a "classical blitzkrieg attack" (Zetterling & Frankson 2000, halaman 137).

- Many of the German participants of Operation Citadel make no mention of blitzkrieg in their characterization of the operation. Several German officers and commanders involved in the operation wrote their account of the battle after the war, and some of these postwar accounts were collected by the U.S. Army. Some of these officers are: Theodor Busse (Newton 2002, halaman 3–27), Erhard Raus (Newton 2002, halaman 29–64), Friedrich Fangohr (Newton 2002, halaman 65–96), Peter von der Groeben (Newton 2002, halaman 97–144), Friedrich Wilhelm von Mellenthin (von Mellenthin 1956, halaman 212–234), Erich von Manstein (Manstein 1983, halaman 443–449), and others. Mellenthin stated: "The German command was committing exactly the same error as in the previous year. Then we attacked the city of Stalingrad, now we were to attack the fortress of Kursk. In both cases the German Army threw away all its advantages in mobile tactics, and met the Russians (sic - Soviets) on ground of their own choosing." (von Mellenthin 1956, halaman 217) Some of the military historians that make no mention of blitzkrieg in their characterization of the operation are: Mark Healy (Healy 2010), George Nipe (Nipe 2011), Steven Newton (Newton 2002), Dieter Brand (Brand 2003), Bruno Kasdorf (Kasdorf 2000), and others.

- "After Kursk, Germany could not even pretend to hold the strategic initiative in the East." (Glantz & House 1995, halaman 175).

- Source includes: German Nation Archive microfilm publication T78, Records of the German High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) Roll 343, Frames 6301178–180, which confirms Hitler's teleprinter messages to Rommel about reinforcing southern Italy with armoured forces that were already destined to be used for Citadel.

- According to Zetterling & Frankson (2000, p. 18) these figures are for 1 July 1943 and accounts for only units that eventually fought in Operation Citadel (4th Panzer Army, part of Army Detachment "Kempf", 2nd Army and 9th Army). The figure for German manpower refers to ration strength (which includes non-combatants and wounded soldiers still in medical installations). The figures for guns and mortars are estimates based on the strength and number of units slated for the operation; the figure for tanks and assault guns include those in workshops.

- Guderian developed and advocated the strategy of concentrating armoured formations at the point of attack (schwerpunkt) and deep penetration. In "Achtung Panzer!" he described what he believed were essential elements for a successful panzer attack. He listed three elements: surprise, deployment in mass, and suitable terrain. Of these, surprise was by far the most important.(Guderian 1937, halaman 205)

- Over 105,000 in April and as much as 300,000 in June, according to Zetterling & Frankson (2000, p. 22).

- Nikolai Litvin, a Soviet anti-tank gunner present at the battle of Kursk, recalls his experience during the special training to overcome tank phobia. "The tanks continued to advance closer and closer. Some comrades became frightened, leaped out of the trenches, and began to run away. The commander saw who was running and quickly forced them back into the trenches, making it sternly clear that they had to stay put. The tanks reached the trench line and, with a terrible roar, clattered overhead ... it was possible to conceal oneself in a trench from a tank, let it pass right over you, and remain alive." (Litvin & Britton 2007, halaman 12–13).

- This order of battle does not show the complete composition of the Steppe Front. In addition to the units listed below, there are also the 4th Guards, 27th, 47th and 53rd Armies. (Clark 2012, halaman 204). Perhaps the order of battle below represents only the formations relevant to Operation Citadel.

- The air operation is misunderstood in most accounts. The German Freya radar stations at Belgorod and Kharkov in 1943 had only picked up Soviet air formations approaching Belgorod and were not responsible for the failure of the entire Soviet preemptive air strike on the eve of Operation Citadel. (Bergström 2007, halaman 26–27).

- "I urged him earnestly to give up the plan of attack. The great commitment certainly would not bring us equivalent gains."(Guderian 1952, halaman 308)

Remove ads

Rujukan

Sumber

Bacaan lanjut

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads