Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Arlington County, Virginia

County in Virginia, United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Arlington County, or simply Arlington, is a county in the U.S. state of Virginia. The county, which is located in the Washington metropolitan area and the broader Northern Virginia region, is positioned directly across from Washington, D.C., the national capital, on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River. The smallest self-governing county in the United States by area, Arlington has both suburban and urbanized districts, the latter being concentrated around corridors along several Washington Metro lines. Its seat of government is located in the Court House neighborhood, which hosts many of its administrative offices and county courthouse.

Part of the Nacotchtank tribe's territory prior to the establishment of the Colony of Virginia, English colonists began settling in Arlington by the 1670s; the area was eventually designated as part of Fairfax County in 1742. The colonial-era economy was mostly based in tobacco agriculture operated with enslaved labor and indentured servants on large plantations. Following the end of the Revolutionary War, Arlington's planters and yeoman farmers transitioned to other crops. Virginia ceded present-day Arlington to help form the District of Columbia, and from 1801 the area was known as Alexandria County; it was eventually retroceded back to Virginia in 1847 as a result of pressure from Alexandria, which was the county's primary commercial center.

During the Civil War, Arlington formed part of the Union's defenses of Washington, which devastated its landscape and economy. Virginia's Reconstruction era Constitution of 1870, in addition to administratively separating Arlington from Alexandria, empowered its black community to participate in local and state elections, which changed the political dynamics of the county until local conservative Southern Democrats succeeded in re-establishing white supremacy by the 1880s. This facilitated the institution of Jim Crow laws and racial segregation in Arlington by the early 20th century. Developers and local politicians further ingrained these practices in Arlington as it experienced a boom in suburbanization with its expanding interurban trolley network starting in the 1880s and a continued influx of federal employees into the 1950s. Despite opposition from Virginia's massive resistance campaign and other groups, Arlington became the first county in Virginia to desegregate its schools in 1959, and its businesses in 1960 after a series of sit-in protests.

Arlington's modern economic development has been greatly influenced by its Metrorail lines, which through deliberate planning starting in the 1960s have become the center of its urban corridors. Many federal government agencies and complexes, including the Pentagon, which houses the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense, are based in Arlington. Government contractors that serve these organizations and others in the Washington metropolitan area, such as Boeing and RTX Corporation are also located within the county. While the public sector is a primary driver of Arlington's economy, tech firms with private sector operations, including Amazon, have established regional headquarters or offices in Arlington's business districts over the past several decades. Institutions of higher education such as Marymount University, George Mason University, Virginia Tech, and the University of Virginia have either main or satellite campuses within Arlington. Arlington is also known as the location of Arlington National Cemetery, a military cemetery established in 1864 where more than 400,000 members of the U.S. Armed Forces are buried. Sites at the cemetery such as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier attract thousands of visitors annually. It is also home to other prominent military memorials, including the Marine Corps War Memorial and Air Force Memorial.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Native American settlement

Arlington County was inhabited by prehistoric Native American cultures from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians 10,000 years before European colonization.[4] Archeological evidence, including pottery fragments, tools, and arrowheads, suggests sporadic habitation during the Archaic Period, with more permanent communities during the Formative stage and Early Woodland period.[5] Some objects unearthed during archeological digs have been found to be from as far as southern Ontario, indicating the existence of a trade route that ran through the area.[6]

When John Smith made contact in 1608, Arlington was populated by the Nacotchtank, an Eastern Algonquian-speaking people that were likely part of the Powhatan Confederacy.[7] He identified a village named Nameroughquena near the present-day 14th Street bridges.[7] The Nacotchtank farmed, hunted, and fished along the nearby Anacostia River, where they had more villages.[8]

Later in the 17th century, the Nacotchtank became involved in the regional beaver trade instigated by Henry Fleete, which while enabling the Nacotchtank to build wealth, undermined traditional social structures and ultimately weakened them.[9] Further pressures, including population loss due to the spread of infectious diseases from Europeans, warfare with encroaching British colonizers, and conflict with Native American tribes in northern regions forced the Nacotchtank to abandon their homeland.[10][7] By 1679, they had fully left the area and were absorbed into the Piscataway.[7]

Colonial era

Colonists began migrating from Jamestown and towards the Potomac River between 1646 and 1676, during which land speculation in the region increased substantially.[11] Early grants were issued in the mid-17th century by the Governor on behalf of the Crown to prominent figures of Virginia society; many never inhabited their landholdings during this period.[11][12] The first "seated" grant in the area was the Howson Patent, which John Alexander purchased from Captain Robert Howson on November 13, 1669, and populated with tenants by 1677.[13] With the establishment of the Northern Neck Proprietary after the restoration of Charles II in 1660, future land grants in the region were made by inheritors of Northern Neck, namely the Lords Fairfax.[14]

After colonists depopulated the area in the aftermath of Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, migration to Northern Neck began to grow by the end of the 17th century. The increase in population justified the formation of Prince William County from parts of Stafford County in 1730, and in 1742 Fairfax County, of which present-day Arlington County was part.[15] Early settlement patterns were defined by large plantations along waterways, where planters built wharfs that provided access to colonial trade networks.[16] This included Abingdon Plantation, which was established by John Alexander's grandson Gerard by 1746 and was the Arlington area's first mansion house.[17][18] Log cabins, such as the home built by John Ball in the mid-18th century, were common among Arlington's yeoman farming community.[19]

Indentured servants and enslaved labor worked the land, the latter of which are first documented being in the Arlington area in 1693 and were owned by the wealthiest planters, such as the Masons and Washingtons.[20][21] Tobacco was the dominant crop grown in Arlington until local soil was exhausted by the late 18th century, motivating tobacco planters to move further inland; remaining farmers turned to growing alternatives such as corn.[18][22] Colonists also built gristmills along Arlington's creeks and engaged in fishing along the Potomac.[23] Rudimentary roads, some of which were first established by Native Americans, and ferries along the Potomac connected residents and plantations with emerging towns such as Alexandria and Georgetown.[24] The former served as the region's primary shipping and commercial district.[25]

Revolutionary war and formation of federal district

The Stamp Act and Townshend Acts passed by the Parliament of Great Britain in the 1760s motivated planters and farmers in Fairfax County, including George Mason, George Washington, and members of the Ball family to sign agreements not to import or purchase British goods in protest.[26] Mason later authored the Fairfax Resolves in 1774 in opposition to the policies, which were adopted by him and other landowners.[26]

Following the Richmond Convention in 1776, Fairfax County established a Committee of Safety that collected taxes for the war effort and enforced bans on trade with Britain.[27] Local Fairfax militia formed before the war were dissolved after the Richmond Convention ordered for the organization of a regular state force in July 1775.[28] Men were recruited from Fairfax County and joined the Virginia state regiment that were incorporated into the Continental Army by 1776.[29] While the area did not see significant action during the war, Alexandria was the home port for part of the Virginia State Navy; some ships operated as privateers.[30] Part of Rochambeau's forces likely camped near Theodore Roosevelt Island on their way to Yorktown in 1781.[31]

After American independence from the British Empire was achieved following the Treaty of Paris and the Constitution was instituted in 1789, the federal government set about establishing the United States' seat of government, which Article 1, Section 8 enabled through the power to acquire an area of no more than ten square miles for the nation's capital.[32] The Residence Act passed by Congress on July 17, 1790, which decreed that the federal district be located on the Potomac River between the "mouths of the Eastern Branch and the Conogochegue", settled the rivalry between states on claiming the location of the capital city.[32] President George Washington commissioned a survey to define its borders, which reached down to Hunting Creek and were consequently beyond the Residence Act's limits; this required an amendment that was passed on March 3, 1791.[32]

In 1789, Virginia had offered to cede ten square miles or less and provide funding for the construction of public buildings. Congress accepted this as a part of the federal district, but specified that no public buildings would be erected in the Virginia section of the capital.[32] Boundary stones were placed at one miles intervals along the borders of the district starting on April 15, 1791.[32] The federal government and Congress moved to the new city of Washington within the District of Columbia in 1800; the Virginia section, which included Alexandria, became known as Alexandria County through the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.[33]

Antebellum period

In the early 19th century, the land outside of Alexandria, termed the "country part" of Alexandria County and representative of present-day Arlington, remained rural and dominated by several large plantations and smaller farms. Migration from northern states such as New York and Pennsylvania brought investment and improved farming methods.[34] Small communities established along the intersections of Alexandria County's growing road network, including Ball's Crossroads, became gathering places for local residents.[35] The county's free black population, which consistent of 235 individuals outside of Alexandria in 1840, lived throughout the area in small clusters and among white neighbors.[36] While agriculture, particularly of corn and grain, was the county's main economic output in the first half of the 19th century, some residents worked in various trades and factories in Alexandria.[37] Other non-farming occupations included fishing and brickmaking.[38]

Enslaved African Americans consisted of around 26% of the population in 1810, working on properties such as George Washington Parke Custis's Arlington Plantation, which Custis established with his inheritance from John Parke Custis, step-son of George Washington, in 1802; this included 18,000 acres of land across Virginia and 200 slaves, 63 of which worked on building and maintaining the plantation.[39][40] The prominent African American Syphax family, whose matriarch Maria Carter Syphax was an illegitimate daughter of Custis and enslaved maid Arianna Carter, originated as enslaved servants on the Arlington estate; Custis later manumitted Maria and her children in 1845 and granted them 17 acres of land.[41][42] Custis was the largest slave owner in the area until his death in 1857.[18]

The population share of the enslaved dropped to around 20% by 1840 as a consequence of the continued movement away from labor-intensive tobacco farming and the slave trade with Deep Southern states and territories.[18] Alexandria became a national center of this trade, with firms like Franklin & Armfield pioneering in the trafficking of enslaved people from around the Chesapeake region to New Orleans and the Forks in the Road slave market in Natchez, where they were sold to the Deep South's growing cotton plantations.[43]

Major infrastructure, including the Chain Bridge, Long Bridge, and Aqueduct Bridge, was built in the first half of the 19th century to better connect the District of Columbia with the surrounding region.[44] Toll roads were established between Alexandria, Georgetown, Leesburg, and other major settlements to facilitate the improvement and maintenance of thoroughfares, some of which also funded bridge construction.[45] The Alexandria Canal, which via the 1843 Aqueduct Bridge connected Alexandria to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in Georgetown, was opened in 1846.[46] Alexandria County's first railway, the Alexandria and Harper's Ferry Railroad, was chartered in 1847; it later became part of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad.[47] Infrastructure expansion drove the Jackson City speculative development, which was established in 1835 by a group of investors from New York at the foot of Long Bridge. Their vision of Jackson City as a rival port to Georgetown and Alexandria was never realized, as the settlement failed to receive a charter from Congress owing to opposition from residents Georgetown and Washington.[48]

Retrocession

The reintegration of Alexandria County into Virginia had been raised intermittently since the formation of the District, particularly by townspeople in Alexandria.[46] Congressional debate of the issue began with discussion of the 1801 Organic Act and its implications, focusing on the lack of political rights afforded to District residents,[51] who were not permitted to vote or have representation in Congress.[52] Economic concerns relating to insufficient federal investment in infrastructure like the Alexandria Canal, which left Alexandria heavily indebted, motivated merchants and leaders in Alexandria to consider retrocession by the 1830s.[53] The argument went that rejoining Virginia would bring financial relief to the municipal budget, greater support for economic development, restored political rights, and free Alexandria County from "antiquated" statutes Congress had inherited from older colonial laws and not updated.[54]

Congress's failure to recharter banks in the District further frustrated Alexandria's business community,[55] and in 1840 the Common Council of Alexandria convened a county-wide referendum on retrocession, with a majority voting in favor.[56] After several years of lobbying by a committee of Alexandrians, the Virginia General Assembly introduced state legislation in July 1846 to accept Alexandria County back into Virginia territory if Congress agreed.[56] Congress passed the Retrocession Act later that month that authorized the return of Alexandria County to Virginia pending another county referendum.[57]

"The act of retrocession is an act in clear and obvious hostility to the spirit and provisions of the constitution of the United States, and beyond the possibility of honest doubt, null and void; That therefore we respectfully invoke the senate and house of assembly to disregard and give no countenance or head to any so-called commissioners or representative pretending or purporting to speak for and in behalf of the citizens of the county of Alexandria, and more especially of the citizens of the country part of the same."

Committee of Nine, Memorial to Governor of Virginia. December 2, 1846 [58]

The referendum, held on September 1 and 2, passed with overwhelming support from Alexandrians, but was rejected by residents in the broader county;[57] many in Alexandria County questioned the constitutionality of retrocession and felt marginalized by a movement that was primarily driven by Alexandria's business interests.[59] George Washington Parke Custis, who had originally opposed retrocession due to concerns about the county's finances, changed sides after the Virginia General Assembly agreed to take on the debt incurred by the Alexandria Canal construction.[57][58] Alexandria County was officially returned to Virginia on March 13, 1847, after the Virginia General Assembly passed the state's retrocession bill.[60]

Beyond the freeholding whites in Alexandria County who were able to participate in the referendum, Alexandria County's free black community was also opposed to retrocession, as they anticipated the pro-slavery Virginia government would encroach upon their rights and institutions. This fear was realized soon after retrocession, when Virginia closed most of Alexandria County's black schools and imposed Black Codes upon all free African Americans.[61][62]

While not mentioned prominently in contemporary debates about retrocession, modern historians and other figures have since argued that the future of slavery in Alexandria and Virginia more broadly was a significant factor.[63] Growing domestic and international abolitionist sentiments stoked fears in Alexandria that slavery would eventually be abolished in the District of Columbia and by extension threaten the town's lucrative slave trade.[64] This ultimately came to pass as a part of the Compromise of 1850, which banned Washington's slave trade.[65] In 1907, Alexandria County attorney Crandal Mackey wrote that, given Alexandria County's existence as a destination for runaway enslaved people, Alexandrians thought they would be better served by the enforcement of slaveowners' property rights that would be guaranteed by Virginia's pro-slavery government.[66] Retrocession also enabled the pro-slavery faction of the Virginia General Assembly to add two safe seats, strengthening their position against non-slave owning, abolitionist-leaning constituencies in Western Virginia.[57][66]

Civil War

The "country part" of Alexandria County leaned strongly Unionist, as indicated by the results of the May 23, 1861 vote held on the ratification of Virginia's Ordinance of Secession; despite reports of voter intimidation from secessionists, two-thirds voted against the Ordinance.[67] This was in part a result of the migration from northern states into Arlington County during the first half of the 19th century, some of whom were sympathetic to abolitionism and the Republican Party.[68] Regardless, Virginia voted overwhelmingly in favor of secession and joined the Confederacy.[69] Robert E. Lee, a colonel in the U.S. Army, son-in-law of George Washington Parke Custis, and owner of Arlington Plantation following Custis's death, left for Richmond with his family on April 22, 1861, to accept command of Virginia's army.[70]

Union occupation

The proximity of Alexandria County to Washington, as well as the direct lines of sight it offered to important landmarks, necessitated the construction of defenses to protect the capital.[71] After engaging in brief reconnaissance activities, the Union Army moved three units into Alexandria County on the night of May 23, 1861, with commanding officer General Joseph K. Mansfield establishing a regional headquarters at Arlington Plantation.[71] Work began immediately on a series of fortifications that eventually became the Arlington Line of the Civil War Defenses of Washington. These included forts and rifle trenches along Arlington Heights, thoroughfare intersections, and bridgeheads.[71][72] The Confederate victory at the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 increased the urgency of completing Washington's defenses,[73] which were mostly finished by the end of that year.[74] The Union Army also built roads, such as Military Road, to enable improved communications and transport along the defensive line.[75] Construction of forts and improvements continued up to 1863.[75]

The Union occupation significantly altered the landscape of Alexandria County. Defensive works required the logging of forests and trenches that cut through farmland.[76] Union troops repurposed private homes and public buildings as hospitals and other facilities.[77] Many properties were left decimated following troop encampments and the razing of structures for timber and other resources.[78] Confederate sympathizers, many of whom were local officials, left after the arrival of Union soldiers, which created gaps in governance; General William Reading Montgomery addressed this by creating a military court that tried military and civilian cases, which was eventually closed after local criticism.[79]

Military engagements

Throughout the war, Alexandria County only saw minor skirmishes between Union and Confederate forces. Confederate parties began engaging in guerrilla tactics against Union outposts in early June 1861,[80] including a minor clash at Arlington Mill on June 2.[81] The most significant battle took place in August 1861 at Ball's Crossroads, when Confederates stationed at Munson's Hill in Fairfax County penetrated the Union line as far as Hall's Hill, which they shelled before being driven back by Union cavalry.[82][83] Union forces also operated the Balloon Corps in Alexandria County until 1863 to perform aerial reconnaissance on nearby Confederate encampments and activities.[84]

Arlington Cemetery and Freedman's Village

Congress's June 1862 enactment of an assessment of taxes owed by Southern property owners, and subsequent enforcement of tax collection, resulted in the Lee family owing $92.07 on Arlington plantation.[85] Mary Anna Custis Lee sent a relative to pay this, which was rejected given her absence.[85] The federal government then seized Arlington estate and purchased it at a public auction held on January 11, 1864, on orders from President Abraham Lincoln.[86] Following this purchase, the Quartermaster General's Office, in search of a burial site for the many Union casualties at the Battle of the Wilderness, selected Arlington in May 1864 for its scenic beauty and association with Robert E. Lee.[87] The first military burial took place on Mary 13, 1864, around one month before the cemetery was officially established.[88]

The rise in contraband migrants from the South into Washington, and the overcrowded camps that accommodate them, motivated the Department of Washington to establish the Freedman's Village settlement for emancipated enslaved people on the grounds of Arlington.[89][90] Founded on December 4, 1863, Freedman's Village, unlike other contraband camps, was envisioned as a model community for African Americans transitioning out of enslavement.[90] The Village provided its inhabitants with instruction in trades, housekeeping, and general education; many were employed by the Union Army and paid a regular wage.[91] Secretary of State William H. Seward often toured prominent visitors around Freedman's Village to demonstrate the Villagers' progress.[92] Many organizations, including churches and fraternities, were founded by Villagers during this period that became the social foundation of Arlington's black community.[93]

Reconstruction through 1900

Years of occupation by Union troops left Alexandria County's economy in poor condition after the war; thousands of acres of farms and woodland had been destroyed.[94] Local landowners who applied for compensation through the Southern Claims Commission generally received much less than they requested.[78] Some financially ruined residents sold off parcels of land at low rates to formerly enslaved people migrating into Alexandria County from rural Virginia and Maryland, eventually creating black enclaves like Hall's Hill.[95]

Changes in municipal governance in Virginia's 1870 Constitution required that all counties be divided into three or more districts, excluding any cities with a population greater than 5,000. This administratively separated Alexandria from the rest of the county and divided Alexandria County into the Arlington, Jefferson, and Washington Districts, with each having its own elected offices, public schools, and other facilities.[96][97] The Reconstruction Amendments passed along with the 1870 Constitution enabled Alexandria County's eligible black voters to participate in district and county-level elections, resulting in local black politicians, such as John B. Syphax, rising to elected office.[98] This was especially the case in the Jefferson District, which contained Freedman's Village and became a center of black political power in the county.[98]

While this constituency was initially associated with the Republican Party, the rise of Virginia's Conservative Party, which opposed black suffrage and other Reconstruction-era reforms,[99] eventually led to the Republicans abandoning their commitments to racial equality.[100] Dissatisfied black voters, as well as white working class communities associated with the labor movement, flocked to the Readjuster Party, a newly established progressive populist party that opposed Virginia's old planter establishment and controlled the General Assembly by 1879.[100][101]

White conservatives that wanted to reinstate their political and social dominance challenged the ascendency of Alexandria County's black community by the 1880s. Through an orchestrated smear campaign in the local press, they contributed to the closure of Freedman's Village in 1887, which had by that point lost the support of the federal government.[102][103] White conservatives also prevented elected black officials from taking office either through claims about "inexperience" or identifying failed payments of election dues.[102] This occurred during a broader political shift in Virginia towards Southern Democrats, who successfully undermined the Readjuster Party's interracial coalition with a reactionary, racist platform by 1885.[104]

Starting in the 1880s, local railroad companies began constructing an interurban trolley system in Alexandria County that eventually provided commuter services to Washington by 1907.[105] This facilitated the establishment of suburban subdivisions, such as Clarendon, along the trolley lines by 1900.[105] Population growth, as well as the inconvenience of running the county's affairs from the old courthouse in Alexandria, drove the General Assembly to enact legislation that enabled residents to vote if the courthouse should be relocated.[106] After a majority voted in favor of the motion, the county's new courthouse was completed on the old site of Fort Woodbury in 1898.[106]

20th century suburbanization and Jim Crow segregation

In the first several decades of the 20th century, Alexandria County, officially renamed to Arlington County after the Arlington estate in 1920,[107] rapidly developed into a commuter suburb of Washington. The ten-year period between 1900 and 1910 saw the creation of 70 new communities and subdivisions.[108] Community organizations were established in these neighborhoods to advocate for their residents.[109] During this period, the City of Alexandria succeeded in annexing significant portions of Arlington's southern area in 1915 and 1929; further annexations were prevented by the General Assembly in 1930.[110]

Developers and political figures such as Frank Lyon and Crandal Mackey, who were members of the Southern Progressive movement, advocated for county-wide infrastructure improvements and the removal of "areas of vice" to facilitate continued suburbanization.[111] This included Rosslyn, an interracial neighborhood which had developed a series of gambling halls and saloons beginning in the 1870s.[112] Lyon and Mackey established the Good Citizen's League in the 1890s, which consisted of Arlington's wealthiest and most influential residents, to push for these changes.[111] Consistent with other Southern Progressives during the Jim Crow era, the Good Citizen's League sought to modernize Arlington while maintaining its racial hierarchy through segregation and other means.[111] League members conducted violent "clean up" raids, most infamously in Rosslyn in 1904,[112] participated in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1901–02 that disenfranchised black voters through poll taxes,[113] and developed white suburban subdivisions via racially restrictive housing covenants.[114] By 1930, these figures also succeeded in changing Arlington's system of government, where the districts established in 1870 were abolished and replaced with a county board of five at-large members that appointed a county manager as chief executive. As intended, this diluted the voting power of Arlington's black population and enabled further institution of racial segregation.[115]

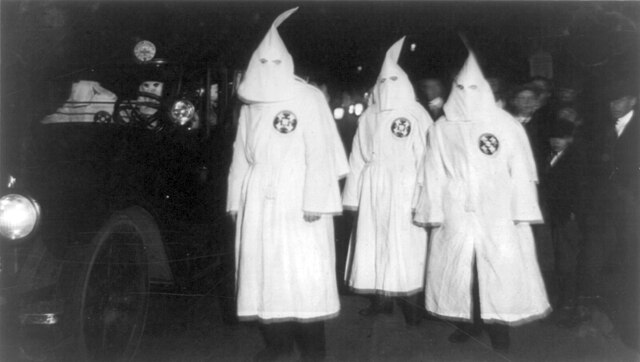

While there were no lynchings in Arlington like elsewhere in the South during the nadir in American race relations, there were recorded instances of racial violence by whites against Arlington's black residents, particularly on its segregated trolley lines. One notable example took place in 1908, when two black passengers traveling to Falls Church, Sandy James and Lee Gaskins, were severely beaten and thrown from a trolley car by a crowd of white people; a mob of 300 white people then gathered in Ballston to search for them on account of an unsubstantiated rumor that James and Gaskins had attempted to derail the trolley. Gaskins was found and sentenced to 10 years in prison despite flimsy evidence, and James was never seen again; Arlington Sheriff Howard Fields later boasted that he had hit James in the head 25 times with a blackjack.[116] Arlington also had an active Ku Klux Klan (KKK) presence during this period, who would participate in community parades and stage cross burnings near black neighborhoods.[117]

The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized "separate but equal" racial segregation enabled the Virginia Assembly to pass zoning ordinances in 1912 that created "segregation districts" throughout the state, which were adopted in Arlington.[118] While these eventually struck down by the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision, county planners and developers restricted the growth of black neighborhoods in other ways, including through Arlington's 1930 zoning ordinance that prevented further construction of more affordable multifamily housing in black communities.[119] The effect of these policies was the stagnation of Arlington's black population, which declined from 38% of Arlington's population in 1900 to around 12% by 1930.[120] Blacks were forced to concentrate in a few overcrowded enclaves as the county's white population increased rapidly with the growth of whites-only suburban subdivisions. These subdivisions gradually encroached upon black neighborhoods, and by 1950 only three black communities remained in the county; 11 had existed in 1900.[121]

New Deal through Civil Rights

Beginning in the New Deal era, Arlington County experienced an inflow of federal workers.[122] While the Great Depression stalled residential development, incoming government employees instigated further growth and the population doubled between 1930 and 1940.[123][124] Public housing projects such as Colonial Village backed by the Federal Housing Administration were built across Arlington to help house its expanding population; consistent with Arlington's Jim Crow policies, these communities were closed off to Arlington's black residents and other minority groups.[125] New Deal programs, such as the Public Works Administration, also supported the continued improvement of Arlington's infrastructure, including the completion of an overhauled sewer system in 1937 and renovations to local public schools.[126][127] Rising car ownership caused the closure of Arlington's trolley lines during the 1930s; these were replaced with a public bus system.[128] Washington National Airport, later renamed after President Ronald Reagan in 1998, opened in 1941 on land formerly occupied by the Abingdon Plantation.[129]

Arlington's population increase fundamentally altered its politics. Its traditional Southern Democratic political establishment, which favored racial segregation and consisted of Southerners in the mold of Mackey and Lyon, was gradually replaced with more liberal, New Deal Democrats and white moderates.[130] These figures fought for greater investment in public education and infrastructure in Arlington, often against opposition in Richmond, where the Democratic Party's socially and fiscally conservative Byrd Machine had dominated the General Assembly since the early 20th century.[131] These developments coincided with a rising civil rights movement in Arlington, reflected in the establishment of its NAACP branch in 1940 and Green Valley resident Jessie Butler's legal challenge to Virginia's poll tax in 1949.[132]

The entry of the U.S. into World War II drove expansion in government that had a significant impact on Arlington County. Massive facilities such as the Pentagon and Navy Annex were built to support military operations.[133] These, along with infrastructure like the Shiley Memorial Highway, required the demolition of Queen City and East Arlington, two historic black communities that had been established shortly after the closure of Freedman's Village.[134][135] The federal government at first housed displaced residents in several trailer camps after an intervention by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt;[136] poor living conditions resulted in both being closed by 1949.[137] Roosevelt further pressured the Federal Public Housing Authority in 1944 to provide more housing to Arlington's African American community, resulting in the construction of a 44-unit public housing project in Johnson's Hill for black residents that year; many leaving the trailer camps moved into this property.[138] By comparison, white residents had access to thousands of public housing units during this period, and none were housed in trailer camps.[138]

Arlington's NAACP and other civil rights organizations continued fighting the county's prevailing racial segregation through a series of legal challenges, particularly after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court ruling that struck down "separate but equal" segregation under Plessy v. Ferguson. Reactionary political forces and organizations, including Virginia's massive resistance program against racial integration in schooling led by former governor and Senator Harry F. Byrd and local Arlington hate groups such as George Lincoln Rockwell's American Nazi Party and the KKK, rose in opposition to this civil rights activism and Arlington's increasing liberalism.[139]

A 1956 lawsuit by NAACP and three residents from Hall's Hill against Arlington's segregation in schooling initiated an extended legal fight that lasted until February 2, 1959, when Stratford Junior High School in Cherrydale was racially integrated with the admission of four black students.[140] The integration, while tense, occurred with relative peace and was dubbed "the day nothing happened" in the local press.[141] In 1960, the Cherrydale sit-ins organized by the Nonviolent Action Group at Howard University resulted in the desegregation of Arlington businesses,[142] and with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, de jure racial housing discrimination in Arlington was officially outlawed.[143]

Arrival of Metro

Arlington County experienced decelerated population growth starting in 1960 as a result of continued migration of residents out to newer suburbs in Fairfax County and Montgomery County; between 1970 and 1980, Arlington lost 21,865 residents.[144] Factors involved in this population shift included new transportation infrastructure that made commuting from more distant communities possible, as well as white flight following the racial integration of Arlington's school system.[145] This change caused its commercial districts, which were also facing competitive pressure from suburban malls, to enter a period of decline.[146]

To revitalize these struggling neighborhoods, the Arlington County government sought to leverage the planned Washington Metro system, which was originally meant to follow the future Interstate 66 freeway.[144] Government planners were otherwise intending to use the provisions under the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act to build a freeway network in Arlington to address growing issues with traffic, which while potentially enabling easier commutes into Washington from outer suburbs, presented concerns about destructive highway construction to Arlington's residents.[144] The County Board also desired to diversify Arlington's economy away from the federal government by attracting more commercial activity.[147] This was reflected in the transformation of Rosslyn, where 19 skyscrapers were completed by 1967.[147]

After extended negotiations, the County Board convinced the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority to run the Orange Line between Rosslyn and Ballston. Residents in this area pushed back based on anticipate high-rise development surrounding the Metro stations.[144] This drove the County Board to adopt its "Bull's Eye" planning model, where higher density development would be concentrated within a walkable distance from the planned Metro stations while maintaining pre-existing single-family zoning beyond a half-mile radius.[144] Both the Orange and Blue Lines were operational by 1979.[144]

As a consequence of reduced rents caused by Orange Line construction, Clarendon became a Vietnamese enclave as refugees migrated to Arlington from Southeast Asia in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.[148] Known by names like "Little Saigon", Clarendon was one of the largest Southeast Asian commercial centers on the East Coast into the 1980s.[149][150] Increased rents and redevelopment following the opening of the Metro in 1979 eventually displaced almost all of Clarendon's Vietnamese businesses by the 1990s;[151] many moved to the Eden Center in Falls Church, which has succeeded Little Saigon as a Vietnamese community hub.[152]

The opening of the Metro stimulated another period of rapid growth. As planned, the corridor between Rosslyn and Ballston experienced revitalization driven by mixed-used, transit-oriented development.[144] Other areas near Blue line stations, such as Pentagon City, also became urbanized with numerous office complexes and retail centers like the Pentagon City Mall that opened in 1989.[144] As a result, Arlington increasingly transitioned away from being solely a commuter suburb of Washington and towards becoming an edge city with business and commercial districts.[153]

2000 through present

On September 11, 2001, The Pentagon was targeted as a part of the September 11 attacks, when American Airlines Flight 77 was hijacked and crashed into the building by five Al-Qaeda terrorists. The attack killed all 64 passengers and 125 people in the Pentagon, and is memorialized by the National 9/11 Pentagon Memorial located on the grounds of the complex.[154]

In recent years, Arlington's highly educated workforce, proximity to Washington, and financial incentives offered by the government have encouraged multinational corporations, including Amazon and Boeing, to establish corporate headquarters in Arlington's business districts.[155] New residents, including immigrants of Asian and Hispanic background, that have arrived since the passing of the 1965 Immigration Act have substantially increased Arlington's racial and ethnic diversity, altering the county's historical white-black demographic profile.[145] Some communities, such as Arlington's historically black neighborhoods, have experienced gentrification into the 21st century, driving rising costs of living.[156]

In 2020, Arlington County pursued a missing middle housing study to evaluate solutions to ongoing issues with county's inadequate housing supply, lack of housing options, and increasing housing costs.[157] Following the completion of this study and community engagement, the County Board officially adopted the Expanded Housing Options (EHO) zoning ordinance on March 22, 2023 to allow construction of up to 6 units on lots zoned for single-family housing, with the goal of increasing Arlington's housing supply and relieving upward pressure on the cost of housing.[158] As of 2025, a successful lawsuit filed by neighborhood organizations opposed to the EHO policy has blocked the measure, which is currently moving through appeal.[159]

Remove ads

Geography

Summarize

Perspective

Arlington County, which is located in the Washington metropolitan area and the Northern Virginia region, is surrounded by Fairfax County and Falls Church to the west, the city of Alexandria to the southeast, and Washington, D.C. to the northeast across the Potomac River. It occupies 26 square miles and is the smallest self-governing county in the United States.[1] Arlington is mostly within boundaries that were defined when it was made part of the District of Columbia in 1791; Arlington's irregular southeast border with Alexandria developed after several annexations by Alexandria that took place in the first half of the 20th century and was finalized in 1966.[160][161]

Geology and terrain

Arlington County exists on a fall line between the Appalachian Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain.[162] The fall line between these geologic provinces follows Interstate 66 between Rosslyn and Four Mile Run, and cuts south to the county border around U.S. Route 50.[162] Arlington's Piedmont terrain is characterized by highly eroded rolling hills; the county's highest prominence, Minor's Hill, is in this area and rises 451 feet above sea level.[162] The Coastal Plain is generally flat. Arlington is drained by Four Mile Run, Pimmit Run, and other small streams that all flow into the Potomac River.[162] Some of these waterways have deep valleys that have been cut by erosion.[162]

Climate

Arlington County has a humid subtropical climate that is characterized by hot, humid summers, mild to moderately cold winters. Based on climate data captured at the National Weather Service's Reagan National Airport station, regional seasonal extremes vary from average lows of 14.3 °F (−10 °C) in January to average highs of 98.1 °F (37 °C) in July. Annual precipitation averages at 41.82 inches, with an average low of 2.86 inches in January and average high of 4.33 inches in July. Average annual snowfall is 13.7 inches, with most occurring in February.

Arlington can experience extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and blizzards. These have included Agnes in 1972, Isabel in 2003, and the 2010 "Snowmaggedon" snowstorm; both hurricanes caused severe flooding and property damage,[163][164] and the 2010 blizzard brought over 13 inches of snowfall in some areas.[165] Extreme flooding of waterways such as Four Mile Run has in the past caused extensive damage to residential neighborhoods, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s before parts of the stream were channelized by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1980s; this was a result of the county's rapid 20th century development, much of which occurred before the introduction of modern stormwater management regulations.[166] Growth in Arlington's impervious surfaces, the majority of which has been driven by redevelopment of single family homes, has continued to present challenges to the county's stormwater management.[166] Localized flooding events after intense rainfall, particularly during the summer months, have occasionally been destructive to residential neighborhoods and infrastructure. For example, a July 2019 weather event later categorized as an 150-year storm resulted in hourly rainfall rates of 7 to 9 inches, which caused Four Mile Run to rise 11 feet within an hour.[167] This has required the periodic dredging of Four Mile Run to ensure it can accommodate for 100-year storms.[168] Due to global climate change, the frequency and extremity of these occurrences has increased in recent years; this trajectory is expected to continue as the broader climate warms.[169][170]

Urban landscape

Since the opening of Metro service in the 1970s, Arlington County has become heavily urbanized; the local government has actively encouraged this via its smart growth, "Bull's Eye" urban planning model, where high density, mixed-use development is promoted within walking distance of Metro stations.[176] Adopted in the county's General Land Use Plan (GLUP) since 1975, the impact of this policy is evident in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor along the Orange and Silver lines and in the Richmond Highway Metro corridor along the Blue and Yellow Lines.[176][177] County planners have termed neighborhoods within the corridors as "urban villages", where each is intended to have unique amenities and characteristics.[177] These areas are rated highly for their walkability, access to public transit, and environmental sustainability, which align with design principles formulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1996.[176] Arlington's approach to urban planning has been recognized by several organizations, including the EPA, which awarded Arlington with its National Award for Smart Growth Achievement for Overall Excellence in Smart Growth in 2002,[178] and the American Planning Association, which awarded Arlington's GLUP with its National Planning Achievement Gold Award for Implementation in 2017.[179]

Outside of its urban districts, Arlington is mostly residential and suburban in character; single-family homes consisted of around 75% of its total land area in 2023.[180] Garden apartment complexes, which were built most prolifically between the New Deal era and the post-war period, exist throughout the county.[181] Several major arterial roads and highways, including Interstate 395, Interstate 66, U.S. Route 50, and U.S. Route 1 run through Arlington and connect it with the broader Washington metropolitan area.[182]

Ecology

Arlington's urbanization during the 20th century greatly impacted its local ecosystem, with many of its natural stream, wetland, and forest environments being buried, reclaimed, or removed to facilitate development; a 2011 study found that only around 738 acres of land, or 4.4% of the total land area in the county, qualified as "historical natural areas".[183] Animals that have adapted well to these conditions, including raccoons and red foxes, are abundant.[184] White-tailed deer, which were mostly eradicated from Virginia by 1900, have rebounded significantly in Arlington since reintroduction and conservation programs were instituted statewide beginning in the 1940s;[185] the county is working to develop a plan to actively manage deer to address concerns about overpopulation.[186] Around half of plants found in the county are non-native; invasive species, including numerous varieties of vine such as English Ivy and Kudzu, have been documented in Arlington.[187]

Arlington has attempted to address its environmental degradation, particularly in its watershed,[188] which has been partially restored over the past several decades to improve local water quality and provide habitat for local wildlife.[189] Past projects have included the installation of living shorelines populated with native plants, removal of invasive vegetation along the lower Four Mile Run, and the conversion of stormwater catchment ponds into wetland habitats.[190][191] One 2011 restoration initiative revived a globally rare Magnolia bog ecosystem that was discovered in Barcroft Park.[192] These efforts have provided enhanced habitats for Arlington's many native mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects.[193] Native fish that inhabit Arlington's waterways include American eel, Eastern blacknose dace, and White sucker; invasive species like snakehead and carp are also present.[194] The county government actively monitors the water quality and ecosystem of its watershed via a series of stream monitoring stations.[195]

Remove ads

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

The 2020 Census found that Arlington County's total population had reached 238,643, which represents growth of 14.9% since the 2010 Census. Arlington's population increase was 9.7% of growth experienced throughout the Northern Virginia region, and 4.9% in Virginia overall.[203] Arlington continued to become more racially and ethnically diverse, with Arlington's Non-Hispanic White population growing 5%, but falling to 58.52% of the total population from 64.04% in 2010. Arlington's Asian population grew by 37.8% – the most of any single-racial group – during this period,[204] and reached a population share of 11.41%. Those that identified as multi-racial or another race not listed in the census had the highest growth rates among all groups.[204] Arlington had a total of 119,085 housing units, representing an increase of 13,681 units from 2010.[205]

According to American Community Survey's 2023 estimates, Arlington's median age is 35.7,[206] with 12.4% of individuals being above 65.[207] Adults aged between 25 and 29 are the largest age bracket and make up 12.8% of the total population.[206] 77.7% of the population has attained a bachelor's degree or higher; 42% of residents have a Master's or professional degree.[208] 21.7% of Arlington's population is foreign-born; 48.4% of this segment are non-U.S. citizens.[209] Married couple family households make up 36.7% of households; 44% of residents have never married.[210]

Remove ads

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

In 2023, Arlington County's GDP totaled $47.3 billion.[211] Given its proximity to Washington, Arlington's economy is especially focused on the federal government, with many of its corporations providing consulting, engineering, or technology services to defense and civilian agencies.[212] As the location of the Pentagon, the Joint Base Myer–Henderson Hall military installation, and other federal institutions, the federal government itself is also a significant contributor to the county's economic activity. Firms with business outside of the federal sector have also set up operations and headquarters in Arlington over the past several decades; the county government has actively pursued this, particularly in the technology space, through tax incentives and other measures.[213]

Employers and workforce

Arlington County's economy is primarily service-based, with a majority of its estimated 221,200 workers employed in professional services, technology companies, and federal, state, and municipal government in 2025; public employees made up around 20% of the workforce.[215] Many private companies with a presence in Arlington serve various government agencies in Washington as contractors, including Deloitte, Booz Allen Hamilton, and Accenture. Large defense and aerospace corporations such as Boeing, RTX Corporation, and Lockheed Martin are either headquartered or have offices in Arlington. Corporations either unaffiliated with or that have operations outside of the public sector, like Amazon, Costar, and Nestlé, have also established themselves in Arlington.[216] Outside of companies and government entities, Arlington also hosts a number of non-profit organizations and advocacy groups.[217]

70% of all jobs in Arlington are within in the county's "planning corridors", which include Rosslyn-Ballston, Richmond Highway, Columbia Pike, and Langston Boulevard; most of Arlington's jobs are located in the Rosslyn-Ballston area.[218] These districts are also home to Arlington's largest retail facilities, such as the Fashion Center at Pentagon City and Ballston Quarter.[219] Work from home arrangements, which spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, continue to persist in the post-pandemic era, with 31.5% of workers working full time from their place of residence in 2023.[220] This has contributed to Arlington's office vacancy rate, which rose to 24.2% in the fourth quarter of 2024 from 14.6% in 2020.[219]

Arlington's unemployment rate, which rose to 4.3% during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, has been consistently under the average for the Washington metropolitan area since at least 2015.[215] High levels of employment in the public sector has made Arlington vulnerable to cuts in federal government spending;[221] this has been particularly acute in the second Trump Administration, during which Arlington's unemployment rate rose to 3.3% in May 2025 as a result of broad spending cuts, layoffs, and contract cancellations across numerous government agencies.[222]

Income and housing

With a mean annual income estimated at $114,097,[223] Arlington is one of the wealthiest municipalities in the United States; 31.3% of households had an annual income of $200,000 or more.[224] Arlington's wealth is not equally distributed geographically or by racial background and tends to be concentrated in its wealthier northern neighborhoods that have a higher share of white households. Arlington's southern areas, which have greater racial and ethnic diversity and a higher population of immigrant families, have lower incomes and higher levels of poverty.[225] This has been attributed to the county's historical underinvestment in the infrastructure and economy of southern Arlington, which is the location of several of Arlington's formerly segregated, historically black neighborhoods.[226] Overall, 7.3% of Arlington residents were below the national poverty level in 2023.[224]

Arlington had an estimated total of 126,540 housing units in 2025, representing 6.3% growth since 2020. 73% of its housing supply consists of multifamily apartments or condos.[227] More than 38% of homes in Arlington are valued at $1 million or more, and the home ownership rate stands at 41.1%.[228] The average rent in 2024 was $2,549;[227] Arlington was identified as one of the most expensive rental markets in the United States outside of California by several real estate firms in 2025.[229] About 8.9% of Arlington's total housing supply consisted of affordable housing units in 2025.[227] Homelessness in Arlington has been trending upwards since 2021; as of 2025, there were 271 homeless individuals, which represented a 12% increase from 2024.[230]

Tourism

According to a 2024 report by the county government, Arlington County attracted 7.1 million visitors in 2023, who generated $6.5 billion in economic activity from a total of $4.5 billion in spending.[231] This activity, which is inclusive of spending at the county's travel centers like Ronald Reagan National Airport, supported 27,567 jobs and is representative of a broader recovery since the COVID-19 pandemic.[231][232] Employment in tourism and hospitality also increased during this period, but has yet to reach parity with pre-pandemic levels.[233]

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Arlington County is within the Northern Virginia region, which has been described as being greatly influenced by its proximity to Washington and its employment opportunities in the federal government; this has attracted highly educated, affluent migrants from other states and countries, ultimately rendering the culture more international and northern in character relative to Virginia's southern regions.[234][235] Consequently, Arlington has communities and enclaves of various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The Columbia Pike corridor, which has been a destination for immigrants since Southeast Asians began arriving after the Fall of Saigon in the 1970s,[236] exemplifies this, and is today home to residents from over 150 different nationalities; it has become particularly known for its wide variety of international food options and venues.[237]

Landmarks and attractions

Arlington is home to Arlington National Cemetery and several prominent military and civilian memorials, including the Air Force Memorial, Marine Corps War Memorial, and the National 9/11 Pentagon Memorial. Arlington National Cemetery attracts more than 3 million visitors annually,[238] with many coming to observe memorials like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which is guarded all year by the U.S. Army 3rd Infantry, the John F Kennedy Gravesite, which memorializes former president John F Kennedy with an eternal flame, and the Military Women's Memorial, which honors all women that have served in the U.S. Armed Forces. Others visit Arlington National Cemetery to pay respects to or grieve for deceased soldiers and relatives; more than 400,000 members of the U.S. Armed Forces are buried in the cemetery.[239] The cemetery offers interpretive group tours and tour bus services to its main memorials.[240] In addition, the National Park Service operates a museum in the historic Arlington House about the history of the Custis plantation, the estate's enslaved laborers and servants, and the life of Robert E. Lee.[241]

Local museums in Arlington include the Arlington Historical Museum, which is located in the 1891 Hume School and run by the Arlington Historical Society,[242] the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington, which details the history of Arlington's black community,[243] and the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington, which is hosted in the historic Clarendon School building and is one of the largest non-federal contemporary art venues in the Washington metropolitan area.[244]

Annual events

Arlington hosts a variety of events every year pertaining to culture and the arts, such as the Arlington County Fair, which was first held in 1977 as an event for local gardening clubs,[245] music festivals such as the Columbia Pike Blues Festival and Rosslyn Jazz Festival,[246][247] and summertime concerts held at the Lubber Run Amphitheater.[248] Major sporting events include the Marine Corps Marathon, whose course has run through Arlington every fall since 1976,[249] and the Armed Forces Association Cycling Classic, a summer road bicycle race which has been held in Arlington's Crystal City and Clarendon neighborhoods since 1998.[250]

Remove ads

Government and politics

Summarize

Perspective

Local government

Since 1930,[261] Arlington County has been governed by a board of supervisors that appoint a County Manager, the latter of which oversees the county's everyday operations, as well as its departments and offices that provide administrative and regulatory services.[262] Each of the board's five members are elected at-large and serving staggered 4-year terms.[263] Since 2023, primary elections for county board seats have been conducted via ranked choice voting.[264] Board members elect a chair, who serves as the official head of county government, and vice-chair at annual organizational meetings held every January.[263] The elected board chair and vice-chair share the same duties and responsibilities of their peers, and do not possess the power to veto motions.[263]

The board oversees various elements of county administration, including general policy, land use and zoning, tax rates, the issuance of proclamations, and the making of appointments to citizen advisory groups.[263] The board also represents Arlington County at regional, state, and national forums and commissions.[263] Other elected county officials include the school board and five constitutional officers, which consist of the County Clerk of the Circuit Court, Commissioner of the Revenue, Commonwealth's Attorney, Sheriff, and Treasurer.[265]

State and federal representation

In Virginia's General Assembly, Arlington County is represented by three members of the House of Delegates from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Districts, and two members of the Senate from Districts 39 and 40.[271] Members of the House of Delegates and Senate serve two-year and four-year terms, respectively.[271]

In the lower chamber of the U.S. Congress, Arlington is part of Virginia's 8th congressional district of the House of Representatives, which is represented by a single Representative elected every two years. Don Beyer, a Democrat, has served in this position since 2015.[272] Virginia's two members in the Senate are elected on six-year terms.[271] These positions have been occupied by Democratic Senators Mark Warner since 2009 and Tim Kaine since 2013.[273][274]

Politics

Historically a conservative Southern Democratic constituency, Arlington County has been liberal Democratic stronghold since the 1980s; a Republican candidate has not won Arlington in state or federal elections since 1981.[276] The Democratic Party has also mostly held Arlington's local elected offices over the last several decades; the election of John Vihstadt, a Republican who ran as an independent, to the county board in November 2014 represented the first non-Democrat to win a county board general election since 1983.[277] The demographic growth seen in Arlington and the broader Northern Virginia region, which is generally affiliated with the Democratic Party, has shifted Virginia's political orientation; largely as a consequence of its more diverse, urbanized regions, it has voted for the Democratic presidential nominee since 2008.[278][279]

Issues that have defined Arlington County politics in recent years have focused on how to manage rising costs of living and the county's housing supply, which has brought into debate the future of single-family zoning laws and community density, as well as lack of affordable housing options for residents.[264] This has been expressed in the controversy surrounding the county board’s EHO housing policy.[264] Also featured in recent elections has been Arlington's elevated office vacancy rates in the post-pandemic era, which have impacted revenue from commercial properties and increased the tax burden of residents for public services.[264]

Remove ads

Education

Summarize

Perspective

Primary and secondary education

Arlington Public Schools operates the county's public K-12 education system, which includes 22 elementary schools, six middle schools, and three high schools.[280] It also runs two specialized secondary education programs at H-B Woodlawn, which adopts an alternative education model,[281] and Arlington Tech, which provides STEM-focused coursework.[282] Arlington Public Schools has 3,000 teachers that serve a student body around 28,000 pupils, making it Virginia's 13th largest public school division.[283] It is governed by a school board composed of five members that are elected in overlapping four-year terms;[284] while board members officially run as non-partisan candidates per Virginia law, political parties are able to endorse them.[285] Arlington also has several private and religious schools, including the Catholic Bishop O'Connell High School.[286]

Colleges and universities

Many universities, such as George Mason University, George Washington University, Georgetown University, Virginia Tech, the University of Virginia, and Northeastern University, operate satellite campuses in Arlington.[287] Marymount University, a private Catholic university established in 1950 by the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary,[288] is the only university with its main campus located in Arlington County.[289]

Remove ads

Transportation

Summarize

Perspective

Roadways

Arterial roads and highways

Arlington County is traversed by two interstate highways: Interstate 66, which runs between the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge and Falls Church, and Interstate 395, which runs between the 14th Street Bridge and Alexandria. Virginia state highways include State Routes 123, 124, 233, 237, and 309. U.S. Routes 1, 29, and 50 also run through the county. All of these highways are operated and maintained by the Virginia Department of Transportation.[290] The George Washington Memorial Parkway, a landscaped parkway which follows Arlington's Potomac River shoreline, is managed by the National Park Service.[291]

Streets

Arlington County's street naming convention, first adopted in 1934 to unify the area's originally unorganized, duplicative street system, uses U.S. Route 50 as the dividing line between northern and southern street designations. Named streets generally run north to south and are ordered alphabetically starting at the Potomac River; this ordering is repeated with additional syllables when the end of the alphabet is reached. Numbered streets run east to west parallel to U.S. Route 50.[292]

Public transit

Arlington County is served by the WMATA Metrorail and Metrobus systems, as well as its local Arlington Transit (ART) bus service.[293] The Orange and Silver Metrorail lines run through Arlington's Rosslyn-Ballston corridor and Falls Church, while the Blue and Yellow lines are located along the Potomac River and the Richmond Highway corridor. Metrobus and ART service provides connections between Metrorail stations, Arlington's neighborhoods, Fairfax County, Alexandria, and Washington.[294][295] The Virginia Railway Express, which provides commuter rail service via the Manassas and Fredericksburg Lines to locations in Alexandria, Fredericksburg, and Fairfax, Prince William, Stafford, and Spotsylvania Counties, has a station in Arlington in its Crystal City neighborhood.[296]

Along with its neighboring municipalities, Arlington County also co-owns the Capital Bikeshare bicycle-sharing system, which as of 2021 has over 100 stations located across the county.[297] The service, which is operated by Lyft,[298] provides traditional bikes and e-bikes.[299]

Airport

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, Arlington's only airport, is located near Gravelly Point on an area of reclaimed land.[300] The airport's non-stop services are mostly to domestic destinations throughout the United States; international flights to locations in Canada, the Caribbean, and Bermuda are also available.[301] It is accessible via the Blue and Yellow Lines at the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport station.[302]

Bicycle and pedestrian routes

Arlington County has a network of bike and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure;[303] Arlington operates around 49 miles of paved trails for hikers and bikers. Major shared-use paths include the WO&D, Custis, Four Mile Run, and Mount Vernon Trails.[304] Arlington has continued to make improvements to its bike infrastructure in recent years, which includes protected bike lanes and trails, and was recognized by the League of American Bicyclists in 2024 as being a Gold-level community for bicycle-friendliness.[305]

Remove ads

Sister cities

Arlington Sister City Association (ASCA) is a nonprofit organization affiliated with Arlington County, Virginia. ASCA works to enhance and promote the region's international profile and foster productive exchanges in education, commerce, culture and the arts through a series of activities. Established in 1993, ASCA supports and coordinates the activities of Arlington County's five sister cities:[306]

Aachen, Germany

Aachen, Germany Coyoacán (Mexico City), Mexico

Coyoacán (Mexico City), Mexico Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine Reims, France

Reims, France San Miguel, El Salvador

San Miguel, El Salvador

Notable people

Notable individuals who reside or who have resided in Arlington County include:

- Patch Adams, social activist and physician

- Aldrich Ames, Soviet double agent

- Warren Beatty, actor

- Sandra Bullock, actress

- Katie Couric, television journalist

- Charles R. Drew, physician and prominent African-American researcher in the field of blood transfusions[307]

- Roberta Flack, musician

- John Glenn, former U.S. Senator and Mercury-Atlas 6 astronaut

- Al Gore, 45th U.S. vice president in the Clinton administration

- Grace Hopper, U.S. Navy rear admiral

- Robert E. Lee, Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War

- Shirley MacLaine, actress

- Jim Morrison, lead singer and songwriter, The Doors[308]

- George S. Patton, U.S. Army general during World War II[309]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads