Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Benito Mussolini

Dictator of Italy from 1922 to 1943 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini[a] (29 July 1883 – 28 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 1943. He was also Duce of Italian fascism upon the establishment of the Italian Fasces of Combat in 1919, and held the title until his summary execution in 1945. He founded and led the National Fascist Party (PNF). As a dictator and founder of fascism, Mussolini inspired the international spread of fascism during the interwar period.[1]

Mussolini was originally a socialist politician and journalist at the Avanti! newspaper. In 1912, he became a member of the National Directorate of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), but was expelled for advocating military intervention in World War I. In 1914, Mussolini founded a newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia, and served in the Royal Italian Army until he was wounded and discharged in 1917. He eventually denounced the PSI, his views pivoting to focus on Italian nationalism, and founded the fascist movement which opposed egalitarianism and class conflict, instead advocating "revolutionary nationalism" transcending class lines. In October 1922, following the March on Rome, he was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. After removing opposition through his secret police and outlawing labour strikes, Mussolini and his followers consolidated power through laws that transformed the nation into a one-party dictatorship. Within five years, he established dictatorial authority by legal and illegal means and aspired to create a totalitarian state. In 1929, he signed the Lateran Treaty to establish Vatican City.

Mussolini's foreign policy was based on the fascist doctrine of spazio vitale ("living space"), which aimed to expand Italian possessions and have an Italian sphere of influence in southeastern Europe. In the 1920s, he ordered the Pacification of Libya and the bombing of Corfu over an incident with Greece, and his government annexed Fiume after a treaty with Yugoslavia. In 1936, Ethiopia was conquered following the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and merged into Italian East Africa (AOI) with Eritrea and Somalia. In 1939, Italian forces annexed Albania. Between 1936 and 1939, Mussolini ordered an intervention in Spain in favour of Francisco Franco, during the Spanish Civil War. Mussolini took part in the Treaty of Lausanne, Four-Power Pact and Stresa Front. However, he alienated the democratic powers as tensions grew in the League of Nations, which he left in 1937. Now hostile to France and Britain, Italy formed the Axis alliance with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

The wars of the 1930s cost Italy enormous resources, leaving it unprepared for the Second World War; Mussolini initially declared Italy's non-belligerence. However, in June 1940, believing Allied defeat imminent, he joined the war on Germany's side, to share the spoils. After the tide turned, and the Allied invasion of Sicily, King Victor Emmanuel III dismissed Mussolini as head of government and placed him in custody in July 1943. After the king agreed to an armistice with the Allies in September 1943, Mussolini was rescued by Germany in the Gran Sasso raid. Adolf Hitler made Mussolini the figurehead of a puppet state in German-occupied north Italy, the Italian Social Republic, which served as a collaborationist regime of the Germans. With Allied victory imminent, Mussolini and mistress Clara Petacci attempted to flee to Switzerland, but were captured by communist partisans and executed on 28 April 1945.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was born on 29 July 1883 in Dovia di Predappio, a small town in the province of Forlì in Romagna. During the Fascist era, Predappio was dubbed "Duce's town" and Forlì was called "Duce's city", with pilgrims going to Predappio and Forlì to see the birthplace of Mussolini.

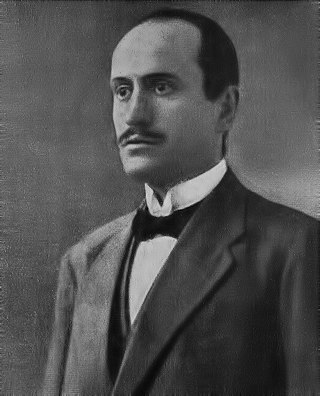

Benito Mussolini's father, Alessandro Mussolini, was a blacksmith and a socialist,[2] while his mother, Rosa (née Maltoni), was a devout Catholic schoolteacher.[3] Given his father's political leanings, Mussolini was named Benito after liberal Mexican president Benito Juárez, while his middle names, Andrea and Amilcare, were for Italian socialists Andrea Costa and Amilcare Cipriani.[4] In return his mother required that he be baptised at birth.[3] Benito was followed by his siblings Arnaldo and Edvige.[5][6]

As a young boy, Mussolini helped his father in his smithy.[7] Mussolini's early political views were strongly influenced by his father, who idolised 19th-century Italian nationalist figures with humanist tendencies such as Carlo Pisacane, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Giuseppe Garibaldi.[8] His father's political outlook combined views of anarchist figures such as Carlo Cafiero and Mikhail Bakunin, the military authoritarianism of Garibaldi, and the nationalism of Mazzini. In 1902, at the anniversary of Garibaldi's death, Mussolini made a public speech in praise of the republican nationalist.[9]

Mussolini was sent to a boarding school in Faenza run by Salesians.[10] Despite being shy, he often clashed with teachers and fellow boarders due to his proud, grumpy, and violent behaviour.[3] During an argument, he injured a classmate with a penknife and was severely punished.[3] After joining a new non-religious school in Forlimpopoli, Mussolini achieved good grades, was appreciated by his teachers despite his violent character, and qualified as an elementary schoolmaster in July 1901.[3][11]

Emigration to Switzerland and military service

In July 1902, Mussolini emigrated to Switzerland, partly to avoid compulsory military service.[2][12] He worked briefly as a stonemason but was unable to find a permanent job.

During this time he studied the ideas of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the sociologist Vilfredo Pareto, and the syndicalist Georges Sorel. Mussolini also later credited Charles Péguy and Hubert Lagardelle as influences.[13] Sorel's emphasis on the need for overthrowing decadent liberal democracy and capitalism by the use of violence, direct action, the general strike, and the use of neo-Machiavellian appeals to emotion, impressed Mussolini deeply.[2]

Mussolini became active in the Italian socialist movement in Switzerland, working for the paper L'Avvenire del Lavoratore (The Future of the Worker), organising meetings, giving speeches to workers, and serving as secretary of the Italian workers' union in Lausanne.[12] John Gunther alleged that Angelica Balabanov introduced Mussolini, then a bricklayer, to Vladimir Lenin.[14] In 1903, he was arrested by Bernese police because of his advocacy of a violent general strike, spent two weeks in jail, and was handed over to Italian police in Chiasso.[12] After he was released in Italy, he returned to Switzerland.[15] He was arrested again in Geneva, in April 1904, for falsifying his passport expiration date, and was expelled from the canton of Geneva.[12] He was released in Bellinzona following protests from Genevan socialists.[12] Mussolini then returned to Lausanne, where he entered the University of Lausanne's Department of Social Science on 7 May 1904, attending the lectures of Vilfredo Pareto.[12][16] In 1937, when he was prime minister of Italy, the University of Lausanne awarded Mussolini an honorary doctorate.[17]

In December 1904, Mussolini returned to Italy to take advantage of an amnesty for desertion from the military. He had been convicted for this in absentia.[12] Since a condition for being pardoned was serving in the army, he joined the corps of the Bersaglieri in Forlì on 30 December 1904.[18] After serving for two years in the military (from January 1905 until September 1906), he returned to teaching.[19]

Political journalist, intellectual and socialist

In February 1909,[20] Mussolini again left Italy, this time to take the job as the secretary of the labour party in the Italian-speaking city of Trento, then part of Austria-Hungary. He also did office work for the local Socialist Party, and edited its newspaper L'Avvenire del Lavoratore (The Future of the Worker). Returning to Italy, he spent a brief time in Milan, and in 1910 he returned to his hometown of Forlì, where he edited the weekly Lotta di classe (The Class Struggle).

Mussolini thought of himself as an intellectual and was considered to be well-read. He read avidly; his favourites in European philosophy included Sorel, the Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, French Socialist Gustave Hervé, Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta, and German philosophers Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the founders of Marxism.[21][22] Mussolini had taught himself French and German and translated excerpts from Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Kant.

During this time, he published Il Trentino veduto da un Socialista (Trentino as viewed by a Socialist) in the radical periodical La Voce.[23] He also wrote several essays about German literature, some stories, and one novel: L'amante del Cardinale: Claudia Particella, romanzo storico (The Cardinal's Mistress). This novel he co-wrote with Santi Corvaja, and it was published as a serial book in the Trento newspaper Il Popolo from 20 January to 11 May 1910.[24] The novel was bitterly anticlerical, and years later was withdrawn from circulation after Mussolini made a truce with the Vatican.[2]

He had become one of Italy's most prominent socialists. In September 1911, Mussolini participated in a riot, led by socialists, against the Italian war in Libya. He bitterly denounced Italy's "imperialist war," an action that earned him a five-month jail term.[25] After his release, he helped expel Ivanoe Bonomi and Leonida Bissolati from the Socialist Party, as they were two "revisionists" who had supported the war.

In 1912, he became a member of the National Directorate of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI).[26] He was rewarded with the editorship of the Socialist Party newspaper Avanti! Under his leadership, its circulation soon rose from 20,000 to 100,000.[27] John Gunther in 1940 called him "one of the best journalists alive"; Mussolini was a working reporter while preparing for the March on Rome, and wrote for the Hearst News Service until 1935.[14] Mussolini was so familiar with Marxist literature that in his writings he would not only quote from well-known Marxist works but also from the relatively obscure works.[28] During this period Mussolini considered himself an "authoritarian communist"[29] and a Marxist and he described Karl Marx as "the greatest of all theorists of socialism."[30]

In 1913, he published Giovanni Hus, il veridico (Jan Hus, true prophet), a historical and political biography about the life and mission of the Czech ecclesiastic reformer Jan Hus and his militant followers, the Hussites. During this socialist period of his life, Mussolini sometimes used the pen name "Vero Eretico" ("sincere heretic").[31]

Mussolini rejected egalitarianism,[32] a core doctrine of socialism.[32] He was influenced by Nietzsche's anti-Christian ideas and negation of God's existence.[33] Mussolini felt that socialism had faltered, in view of the failures of Marxist determinism and social democratic reformism, and believed that Nietzsche's ideas would strengthen socialism. Mussolini's writings came to reflect an abandonment of Marxism and egalitarianism in favour of Nietzsche's übermensch concept and anti-egalitarianism.[33]

Expulsion from the Italian Socialist Party

When World War I began in August 1914, many socialist parties worldwide followed the rising nationalist current and supported their country's intervention in the war.[34][35] In Italy, the outbreak of the war created a surge of Italian nationalism and intervention was supported by a variety of political factions. One of the most prominent and popular Italian nationalist supporters of the war was Gabriele d'Annunzio who promoted Italian irredentism and helped sway the Italian public to support intervention.[36] The Italian Liberal Party under the leadership of Paolo Boselli promoted intervention on the side of the Allies and utilised the Società Dante Alighieri to promote Italian nationalism.[37][38] Italian socialists were divided on whether to support the war.[39] Prior to Mussolini taking a position on the war, a number of revolutionary syndicalists had announced their support of intervention, including Alceste De Ambris, Filippo Corridoni, and Angelo Oliviero Olivetti.[40] The Italian Socialist Party decided to oppose the war after anti-militarist protestors had been killed, resulting in a general strike called Red Week.[41]

Mussolini initially held official support for the party's decision and, in an August 1914 article, Mussolini wrote "Down with the War. We remain neutral." He saw the war as an opportunity, both for his own ambitions as well as those of socialists and Italians. He was influenced by anti-Austrian Italian nationalist sentiments, believing that the war offered Italians in Austria-Hungary the chance to liberate themselves from rule of the Habsburgs. He eventually decided to declare support for the war by appealing to the need for socialists to overthrow the Hohenzollern and Habsburg monarchies in Germany and Austria-Hungary who he said had consistently repressed socialism.[42]

Mussolini further justified his position by denouncing the Central Powers for being reactionary powers; for pursuing imperialist designs against Belgium and Serbia as well as historically against Denmark, France, and against Italians, since hundreds of thousands of Italians were under Habsburg rule. He argued that the fall of Hohenzollern and Habsburg monarchies and the repression of "reactionary" Turkey would create conditions beneficial for the working class, and that the mobilisation required for the war would undermine Russia's reactionary authoritarianism and bring Russia to social revolution. He said that for Italy the war would complete the process of Risorgimento by uniting the Italians in Austria-Hungary into Italy and by allowing the common people of Italy to be participating members in what would be Italy's first national war. Thus he claimed that the vast social changes that the war could offer meant that it should be supported as a revolutionary war.[40]

As Mussolini's support for the intervention solidified, he came into conflict with socialists who opposed the war. He attacked the opponents of the war and claimed that those proletarians who supported pacifism were out of step with the proletarians who had joined the rising interventionist vanguard that was preparing Italy for a revolutionary war. He began to criticise the Italian Socialist Party and socialism itself for having failed to recognise the national problems that had led to the outbreak of the war.[43] He was expelled from the party for his support of intervention.

A police report prepared by the Inspector-General of Public Security in Milan, G. Gasti, describes his background and his position on the First World War that resulted in his ousting from the Italian Socialist Party:

Professor Benito Mussolini, ... 38, revolutionary socialist, has a police record; elementary school teacher qualified to teach in secondary schools; former first secretary of the Chambers in Cesena, Forlì, and Ravenna; after 1912 editor of the newspaper Avanti! to which he gave a violent suggestive and intransigent orientation. In October 1914, finding himself in opposition to the directorate of the Italian Socialist party because he advocated a kind of active neutrality on the part of Italy in the War of the Nations against the party's tendency of absolute neutrality, he withdrew on the twentieth of that month from the directorate of Avanti! Then on the fifteenth of November [1914], thereafter, he initiated publication of the newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, in which he supported—in sharp contrast to Avanti! and amid bitter polemics against that newspaper and its chief backers—the thesis of Italian intervention in the war against the militarism of the Central Empires. For this reason he was accused of moral and political unworthiness and the party thereupon decided to expel him ... Thereafter he ... undertook a very active campaign in behalf of Italian intervention, participating in demonstrations in the piazzas and writing quite violent articles in Popolo d'Italia ...[27]

In his summary, the Inspector also noted:

He was the ideal editor of Avanti! for the Socialists. In that line of work he was greatly esteemed and beloved. Some of his former comrades and admirers still confess that there was no one who understood better how to interpret the spirit of the proletariat and there was no one who did not observe his apostasy with sorrow. This came about not for reasons of self-interest or money. He was a sincere and passionate advocate, first of vigilant and armed neutrality, and later of war; and he did not believe that he was compromising with his personal and political honesty by making use of every means—no matter where they came from or wherever he might obtain them—to pay for his newspaper, his program and his line of action. This was his initial line. It is difficult to say to what extent his socialist convictions (which he never either openly or privately abjure) may have been sacrificed in the course of the indispensable financial deals which were necessary for the continuation of the struggle in which he was engaged ... But assuming these modifications did take place ... he always wanted to give the appearance of still being a socialist, and he fooled himself into thinking that this was the case.[44]

John Gunther alleged that Lenin criticised Italian socialists for having lost Mussolini from their cause.[14]

Beginning of Fascism and service in World War I

After being ousted by the Italian Socialist Party, Mussolini made a radical transformation, ending his support for class conflict and joining in support of revolutionary nationalism transcending class lines.[43] He formed the interventionist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia and the Fascio Rivoluzionario d'Azione Internazionalista ("Revolutionary Fasces of International Action") in October 1914.[38] The funds to create Il Popolo d'Italia—funneled through entrepreneur Filippo Naldi—came from many sources, including domestic industrial and agrarian interests, such as the engineering giants Fiat and Ansaldo, and the governments of France and Britain.[b][45][47][48]

On 5 December 1914, Mussolini denounced orthodox socialism for failing to recognise that the war had made national identity and loyalty more significant than class distinction.[43] He fully demonstrated his transformation in a speech that acknowledged the nation as an entity, a notion he had rejected prior to the war, saying:

The nation has not disappeared. We used to believe that the concept was totally without substance. Instead we see the nation arise as a palpitating reality before us! ... Class cannot destroy the nation. Class reveals itself as a collection of interests—but the nation is a history of sentiments, traditions, language, culture, and race. Class can become an integral part of the nation, but the one cannot eclipse the other.[49]

The class struggle is a vain formula, without effect and consequence wherever one finds a people that has not integrated itself into its proper linguistic and racial confines—where the national problem has not been definitely resolved. In such circumstances the class movement finds itself impaired by an inauspicious historic climate.[50]

Mussolini continued to promote the need of a revolutionary vanguard elite to lead society. He no longer advocated a proletarian vanguard, but instead a vanguard led by dynamic and revolutionary people of any social class.[50] Though he denounced orthodox socialism and class conflict, he maintained at the time that he was a nationalist socialist and a supporter of the legacy of nationalist socialists in Italy's history, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Carlo Pisacane. As for the Italian Socialist Party and its support of orthodox socialism, he claimed that his failure as a member of the party to revitalise and transform it to recognise the contemporary reality revealed the hopelessness of orthodox socialism as outdated and a failure.[51] This perception of the failure of orthodox socialism in the light of the outbreak of World War I was not solely held by Mussolini; other pro-interventionist Italian socialists such as Filippo Corridoni and Sergio Panunzio had also denounced classical Marxism in favour of intervention.[52]

These basic political views and principles formed the basis of Mussolini's newly formed political movement, the Fasci d'Azione Rivoluzionaria in 1914, who called themselves Fascisti (Fascists).[53] At this time, the Fascists did not have an integrated set of policies and the movement was small, ineffective in its attempts to hold mass meetings, and was regularly harassed by government authorities and orthodox socialists.[54] Antagonism between the interventionists versus the anti-interventionist orthodox socialists resulted in violence between the Fascists and socialists. These early hostilities between the Fascists and the revolutionary socialists shaped Mussolini's conception of the nature of Fascism in its support of political violence.[55]

Mussolini became an ally with the irredentist politician and journalist Cesare Battisti.[27] When World War I started, Mussolini, like many Italian nationalists, volunteered to fight. He was turned down because of his radical Socialism and told to wait for his reserve call up. He was called up on 31 August and reported for duty with his old unit, the Bersaglieri. After a two-week refresher course he was sent to Isonzo front where he took part in the Second Battle of the Isonzo, September 1915. His unit also took part in the Third Battle of the Isonzo, October 1915.[56]

The Inspector General continued:

He was promoted to the rank of corporal "for merit in war". The promotion was recommended because of his exemplary conduct and fighting quality, his mental calmness and lack of concern for discomfort, his zeal and regularity in carrying out his assignments, where he was always first in every task involving labor and fortitude.[27]

Mussolini's military experience is told in his work Diario di guerra. He totalled about nine months of active, front-line trench warfare. During this time, he contracted paratyphoid fever.[57] His military exploits ended in February 1917 when he was wounded accidentally by the explosion of a mortar bomb in his trench. He was left with at least 40 shards of metal in his body and had to be evacuated from the front.[56][57] He was discharged from the hospital in August 1917 and resumed his editor-in-chief position at his new paper, Il Popolo d'Italia.

On 25 December 1915, in Treviglio, he married his compatriot Rachele Guidi, who had already borne him a daughter, Edda, at Forlì in 1910. In 1915, he had a son with Ida Dalser, a woman born in Sopramonte, a village near Trento.[11][4][58] He legally recognised this son on 11 January 1916.

Remove ads

Rise to power

Summarize

Perspective

Formation of the National Fascist Party

By the time he returned from service in the Allied forces of World War I, Mussolini was convinced that socialism as a doctrine had largely been a failure. In early 1918 he called for the emergence of a man "ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep" to revive the Italian nation.[59] On 23 March 1919 Mussolini re-formed the Milan fascio as the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Squad), consisting of 200 members.[60]

The ideological basis for fascism came from a number of sources. Mussolini drew from the works of Plato, Georges Sorel, Nietzsche, and the economic ideas of Vilfredo Pareto. Mussolini admired Plato's The Republic, which he often read for inspiration.[61] The Republic expounded a number of ideas that fascism promoted, such as rule by an elite promoting the state as the ultimate end, opposition to democracy, protecting the class system and promoting class collaboration, rejection of egalitarianism, promoting the militarisation of a nation by creating a class of warriors, demanding that citizens perform civic duties in the interest of the state, and utilising state intervention in education to promote the development of warriors and future rulers of the state.[62]

The idea behind Mussolini's foreign policy was that of spazio vitale ('living space'), a concept in Italian Fascism that was analogous to Lebensraum in German National Socialism.[63] The concept of spazio vitale was first announced in 1919, when the entire Mediterranean, especially so-called Julian March, was redefined to make it appear a unified region that had belonged to Italy from the times of the ancient Roman province of Italia,[64][65] and was claimed as Italy's exclusive sphere of influence. The right to colonise the neighbouring Slovene ethnic areas and the Mediterranean, being inhabited by what were alleged to be less developed peoples, was justified on the grounds that Italy was allegedly suffering from overpopulation.[66]

Borrowing the idea first developed by Enrico Corradini before 1914 of the natural conflict between "plutocratic" nations like Britain and "proletarian" nations like Italy, Mussolini claimed that Italy's principal problem was that "plutocratic" countries like Britain were blocking Italy from achieving the necessary spazio vitale that would let the Italian economy grow.[67] Mussolini equated a nation's potential for economic growth with territorial size, thus in his view the problem of poverty in Italy could only be solved by winning the necessary spazio vitale.[68]

Though biological racism was less prominent in Italian Fascism than in National Socialism, right from the start the spazio vitale concept had a strong racist undercurrent. Mussolini asserted there was a "natural law" for stronger peoples to subject and dominate "inferior" peoples such as the "barbaric" Slavic peoples of Yugoslavia. He stated in a September 1920 speech:

When dealing with such a race as Slavic—inferior and barbarian—we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy ... We should not be afraid of new victims ... The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps ... I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians ...

In the same way, Mussolini argued that Italy was right to follow an imperialist policy in Africa because he saw all black people as "inferior" to whites.[71] Mussolini claimed that the world was divided into a hierarchy of races (though this was justified more on cultural than on biological grounds), and that history was nothing more than a Darwinian struggle for power and territory between various "racial masses".[71] Mussolini saw high birthrates in Africa and Asia as a threat to the "white race". Mussolini believed that the United States was doomed as the American blacks had a higher birthrate than whites, making it inevitable that the blacks would take over the United States to drag it down to their level.[72] The fact that Italy was suffering from overpopulation was seen as proving the cultural and spiritual vitality of the Italians, who were thus justified in seeking to colonise lands that Mussolini argued—on a historical basis—belonged to Italy anyway. In Mussolini's thinking, demography was destiny; nations with rising populations were nations destined to conquer; and nations with falling populations were decaying powers that deserved to die. Hence, the importance of natalism to Mussolini, since only by increasing the birth rate could Italy ensure its future as a great power. By Mussolini's reckoning, the Italian population had to reach 60 million to enable Italy to fight a major war—hence his relentless demands for Italian women to have more children.[71]

Mussolini and the fascists managed to be simultaneously revolutionary and traditionalist;[73][74] because this was vastly different from anything else in the political climate of the time, it is sometimes described as "The Third Way".[75] The Fascisti, led by one of Mussolini's close confidants, Dino Grandi, formed armed squads of war veterans called blackshirts (or squadristi) with the goal of restoring order to the streets of Italy with a strong hand. The blackshirts clashed with communists, socialists, and anarchists at parades and demonstrations; all of these factions were also involved in clashes against each other. The Italian government rarely interfered with the blackshirts' actions, owing in part to a looming threat and widespread fear of a communist revolution. The Fascisti grew rapidly; within two years they transformed themselves into the National Fascist Party at a congress in Rome. In 1921, Mussolini won election to the Chamber of Deputies for the first time.[4] In the meantime, from about 1911 until 1938, Mussolini had various affairs with the Jewish author and academic Margherita Sarfatti, called the "Jewish Mother of Fascism" at the time.[76]

March on Rome

In the night between 27 and 28 October 1922, about 30,000 Fascist blackshirts gathered in Rome to demand the resignation of liberal Prime Minister Luigi Facta and the appointment of a new Fascist government. On the morning of 28 October, King Victor Emmanuel III, who according to the Albertine Statute held the supreme military power, refused the government request to declare martial law, which led to Facta's resignation. The King then handed over power to Mussolini (who stayed in his headquarters in Milan during the talks) by asking him to form a new government. The King's controversial decision has been explained by historians as a combination of delusions and fears; Mussolini enjoyed wide support in the military and among the industrial and agrarian elites, while the King and the conservative establishment were afraid of a possible civil war and thought they could use Mussolini to restore law and order, but failed to foresee the danger of a totalitarian evolution.[77]

Appointment as Prime Minister

As Prime Minister, the first years of Mussolini's rule were characterised by a right-wing coalition government of Fascists, nationalists, liberals, and two Catholic clerics from the People's Party. The Fascists made up a small minority in his original governments. Mussolini's domestic goal was the eventual establishment of a totalitarian state with himself as supreme leader (Il Duce), a message that was articulated by the Fascist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, which was now edited by Mussolini's brother, Arnaldo. To that end, Mussolini obtained from the legislature dictatorial powers for one year (legal under the Italian constitution of the time). He favoured the complete restoration of state authority, with the integration of the Italian Fasces of Combat into the armed forces (the foundation in January 1923 of the Voluntary Militia for National Security) and the progressive identification of the party with the state. In political and social economy, he passed legislation that favoured the wealthy industrial and agrarian classes (privatisations, liberalisations of rent laws and dismantlement of the unions).[4]

On 1 November 1922, armed fascists raided the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Mission's Trade Department, broke into the foreign trade agent's office, then abducted and shot one Soviet official, prompting the Soviets to denounce the fascists to the Italian Foreign Ministry.[78] In a letter written before 8 November to Georgy Chicherin, Lenin judged that incident "a very convenient pretext" for the Soviets to "kick at Mussolini and have everyone (Vorovsky and the whole delegation) leave Italy, starting to attack her over her fascists", to "stage an international demonstration", and to "give the Italian people some serious help".[79]

In 1923, Mussolini sent Italian forces to invade Corfu during the Corfu incident. The League of Nations proved powerless, and Greece was forced to comply with Italian demands.

Acerbo Law

In June 1923, the government passed the Acerbo Law, which transformed Italy into a single national constituency. It also granted a two-thirds majority of the seats in Parliament to the party or group of parties that received at least 25% of the votes.[80] This law applied in the elections of 6 April 1924. The national alliance, consisting of Fascists, most of the old Liberals and others, won 64% of the vote.

Squadristi violence

The assassination of the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti, who had requested that the elections be annulled because of the irregularities,[81] provoked a momentary crisis in the Mussolini government. Mussolini ordered a cover-up, but witnesses saw the car that transported Matteotti's body parked outside Matteotti's residence, which linked Amerigo Dumini to the murder.

Mussolini later confessed that a few resolute men could have altered public opinion and started a coup that would have swept fascism away. Dumini was imprisoned for two years. On his release, Dumini allegedly told other people that Mussolini was responsible, for which he served further prison time.

The opposition parties responded weakly or were generally unresponsive. Many of the socialists, liberals, and moderates boycotted Parliament in the Aventine Secession, hoping to force Victor Emmanuel to dismiss Mussolini.

On 31 December 1924, MVSN consuls met with Mussolini and gave him an ultimatum: crush the opposition or they would do so without him. Fearing a revolt by his own militants, Mussolini decided to drop all pretense of democracy.[82] On 3 January 1925, Mussolini made a truculent speech before the Chamber in which he took responsibility for squadristi violence (though he did not mention the assassination of Matteotti).[83] He did not abolish the squadristi until 1927, however.[14]

Remove ads

Prime Minister

Summarize

Perspective

Organizational innovations

German-American historian Konrad Jarausch has argued that Mussolini was responsible for an integrated suite of political innovations that made fascism a powerful force in Europe. First, he proved the movement could actually seize power and operate a comprehensive government in a major country. Second, the movement claimed to represent the entire national community, not a fragment such as the working class or the aristocracy. He made a significant effort to include the previously alienated Catholic element. He defined public roles for the main sectors of the business community rather than allowing it to operate backstage. Third, he developed a cult of one-man leadership that focused media attention and national debate on his own personality. As a former journalist, Mussolini proved highly adept at exploiting all forms of mass media. Fourth, he created a mass membership party with groups that could be more readily mobilised and monitored. Like all dictators he made liberal use of the threat of extrajudicial violence, as well as actual violence by his Blackshirts, to frighten his opposition.[84]

Police state

Between 1925 and 1927, Mussolini progressively dismantled virtually all constitutional and conventional restraints on his power and built a police state. A law passed on 24 December 1925—Christmas Eve for the largely Roman Catholic country—changed Mussolini's formal title from "President of the Council of Ministers" to "Head of the Government", although he was still called "Prime Minister" by most non-Italian news sources. He was no longer responsible to Parliament and could be removed only by the King. While the Italian constitution stated that ministers were responsible only to the sovereign, in practice it had become all but impossible to govern against the express will of Parliament. The Christmas Eve law ended this practice, and also made Mussolini the only person competent to determine the body's agenda. This law transformed Mussolini's government into a de facto legal dictatorship. Local autonomy was abolished, and podestàs appointed by the Italian Senate replaced elected mayors and councils.

While Italy occupied former Austro-Hungarian areas between years 1918 and 1920, five hundred "Slav" societies (for example Sokol) and slightly smaller number of libraries ("reading rooms") had been forbidden, specifically so later with the Law on Associations (1925), the Law on Public Demonstrations (1926) and the Law on Public Order (1926)—the closure of the classical lyceum in Pisino, of the high school in Voloska (1918), and the five hundred Slovene and Croatian primary schools followed.[85] One thousand "Slav" teachers were forcibly exiled to Sardinia and to Southern Italy.

On 7 April 1926, Mussolini survived a first assassination attempt by Violet Gibson.[86] On 31 October 1926, 15-year-old Anteo Zamboni attempted to shoot Mussolini in Bologna. Zamboni was lynched on the spot.[87][88] Mussolini also survived a failed assassination attempt in Rome by anarchist Gino Lucetti,[89] and a planned attempt by the Italian anarchist Michele Schirru,[90] which ended with Schirru's capture and execution.[91]

All other parties were outlawed following Zamboni's assassination attempt in 1926, though in practice Italy had been a one-party state since 1925. In 1928, an electoral law abolished parliamentary elections. Instead, the Grand Council of Fascism selected a single list of candidates to be approved by plebiscite. If voters rejected the list, the process would simply be repeated until it was approved. The Grand Council had been created five years earlier as a party body but was "constitutionalized" and became the highest constitutional authority in the state. On paper, the Grand Council had the power to recommend Mussolini's removal from office, and was thus theoretically the only check on his power. However, only Mussolini could summon the Grand Council and determine its agenda. To gain control of the South, especially Sicily, he appointed Cesare Mori as a Prefect of the city of Palermo, with the charge of eradicating the Sicilian Mafia. In the telegram, Mussolini wrote to Mori:

Your Excellency has carte blanche; the authority of the State must absolutely, I repeat absolutely, be re-established in Sicily. If the laws still in force hinder you, this will be no problem, as we will draw up new laws.[92]

Mori did not hesitate to lay siege to towns, using torture, and holding women and children as hostages to oblige suspects to give themselves up. These harsh methods earned him the nickname of "Iron Prefect". In 1927, Mori's inquiries brought evidence of collusion between the Mafia and the Fascist establishment, and he was dismissed for length of service in 1929, at which time the number of murders in Palermo Province had decreased from 200 to 23. Mussolini nominated Mori as a senator, and fascist propaganda claimed that the Mafia had been defeated.[93]

In accordance with the new electoral law, the general elections took the form of a plebiscite in which voters were presented with a single PNF-dominated list. According to official figures, the list was approved by 98.43% of voters.[94]

"Pacification of Libya"

In 1919, the Italian state had brought in a series of liberal reforms in Libya that allowed education in Arabic and Berber and allowed for the possibility that the Libyans might become Italian citizens.[95] Giuseppe Volpi, who had been appointed governor in 1921, was retained by Mussolini, and withdrew all of the measures offering equality to the Libyans.[95] A policy of confiscating land from the Libyans and granting it to Italian colonists gave new vigor to Libyan resistance led by Omar Mukhtar, and during the ensuing "Pacification of Libya", the Fascist regime waged a genocidal campaign designed to kill as many Libyans as possible.[96][95] Well over half the population of Cyrenaica were confined to 15 concentration camps by 1931 while the Royal Italian Air Force staged chemical warfare attacks against the Bedouin.[97] On 20 June 1930, Marshal Pietro Badoglio wrote to General Rodolfo Graziani:

As for overall strategy, it is necessary to create a significant and clear separation between the controlled population and the rebel formations. I do not hide the significance and seriousness of this measure, which might be the ruin of the subdued population ... But now the course has been set, and we must carry it out to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica must perish.[98]

On 3 January 1933, Mussolini told the diplomat Baron Pompei Aloisi that the French in Tunisia had made an "appalling blunder" by permitting sex between the French and the Tunisians, which he predicted would lead to the French degenerating into a nation of "half-castes", and to prevent the same thing happening to the Italians gave orders to Marshal Badoglio that miscegenation be made a crime in Libya.[99]

Economic policy

Mussolini launched several public construction programs and government initiatives throughout Italy to combat economic setbacks or unemployment levels. His earliest (and one of the best known) was the Battle for Wheat, by which 5,000 new farms were established and five new agricultural towns (among them Littoria and Sabaudia) on land reclaimed by draining the Pontine Marshes. In Sardinia, a model agricultural town was founded and named Mussolinia (it has long since been renamed Arborea). This town was the first of what Mussolini hoped would be thousands of new agricultural settlements across the country. The Battle for Wheat diverted valuable resources to wheat production from other more economically viable crops. Landowners grew wheat on unsuitable soil using all the advances of modern science, and although the wheat harvest increased, prices rose, consumption fell and high tariffs were imposed.[100] The tariffs promoted widespread inefficiencies and the government subsidies given to farmers pushed the country further into debt.

Mussolini also initiated the "Battle for Land", a policy based on land reclamation outlined in 1928. The initiative had a mixed success; while projects such as the draining of the Pontine Marsh in 1935 for agriculture were good for propaganda purposes, provided work for the unemployed and allowed for great land owners to control subsidies, other areas in the Battle for Land were not very successful. This program was inconsistent with the Battle for Wheat (small plots of land were inappropriately allocated for large-scale wheat production), and the Pontine Marsh was lost during World War II. Fewer than 10,000 peasants resettled on the redistributed land, and peasant poverty remained high. The Battle for Land initiative was abandoned in 1940.

In 1930, in "The Doctrine of Fascism" he wrote, "The so-called crisis can only be settled by State action and within the orbit of the State."[101] He tried to combat economic recession by introducing a "Gold for the Fatherland" initiative, encouraging the public to voluntarily donate gold jewellery to government officials in exchange for steel wristbands bearing the words "Gold for the Fatherland". The collected gold was melted down and turned into gold bars, which were then distributed to the national banks.

Government control of business was part of Mussolini's policy planning. By 1935, he claimed that three-quarters of Italian businesses were under state control. Later that year, Mussolini issued several edicts to further control the economy, e.g. forcing banks, businesses, and private citizens to surrender all foreign-issued stock and bond holdings to the Bank of Italy. In 1936, he imposed price controls.[102] He also attempted to turn Italy into a self-sufficient autarky, instituting high barriers on trade with most countries except Germany.

In 1943, Mussolini proposed the theory of economic socialisation.

Railways

Mussolini was keen to take the credit for major public works in Italy, particularly the railway system.[103] His reported overhauling of the railway network led to the popular saying, "Say what you like about Mussolini, he made the trains run on time."[103] Kenneth Roberts, journalist and novelist, wrote in 1924:

The difference between the Italian railway service in 1919, 1920 and 1921 and that which obtained during the first year of the Mussolini regime was almost beyond belief. The cars were clean, the employees were snappy and courteous, and trains arrived at and left the stations on time — not fifteen minutes late, and not five minutes late; but on the minute.[104]

In fact, the improvement in Italy's dire post-war railway system had begun before Mussolini took power.[103][105] The improvement was also more apparent than real. Bergen Evans wrote in 1954:

The author was employed as a courier by the Franco-Belgique Tours Company in the summer of 1930, the height of Mussolini's heyday, when a fascist guard rode on every train, and is willing to make an affidavit to the effect that most Italian trains on which he travelled were not on schedule—or near it. There must be thousands who can support this attestation. It's a trifle, but it's worth nailing down.[106]

George Seldes wrote in 1936 that although the express trains carrying tourists generally—though not always—ran on schedule, the same was not true for the smaller lines, where delays were frequent,[103] while Ruth Ben-Ghiat has said that "they improved the lines that had a political meaning to them".[106]

Propaganda and cult of personality

Mussolini's foremost priority was the subjugation of the minds of the Italian people through the use of propaganda. The regime promoted a lavish cult of personality centered on the figure of Mussolini. He pretended to incarnate the new fascist Übermensch, promoting an aesthetic of exasperated Machismo that attributed to him quasi-divine capacities.[107] At various times after 1922, Mussolini personally took over the ministries of the interior, foreign affairs, colonies, corporations, defence, and public works. Sometimes he held as many as seven departments simultaneously, as well as the premiership. He was also head of the all-powerful Fascist Party and the armed local fascist militia, the MVSN or "Blackshirts", who terrorised incipient resistance in the cities and provinces. He would later form the OVRA, an institutionalised secret police that carried official state support. In this way he succeeded in keeping power in his own hands and preventing the emergence of any rival.

All teachers in schools and universities had to swear an oath to defend the fascist regime. Newspaper editors were all personally chosen by Mussolini, and only those in possession of a certificate of approval from the Fascist Party could practice journalism. These certificates were issued in secret; Mussolini thus skilfully created the illusion of a "free press". The trade unions were also deprived of any independence and were integrated into what was called the "corporative" system. The aim was to place all Italians in various professional organisations or corporations, all under clandestine governmental control.

Large sums of money were spent on highly visible public works and on international prestige projects. These included as the Blue Riband ocean liner SS Rex; setting aeronautical records with the world's fastest seaplane, the Macchi M.C.72; and the transatlantic flying boat cruise of Italo Balbo, which was greeted with much fanfare in the United States when it landed in Chicago in 1933.

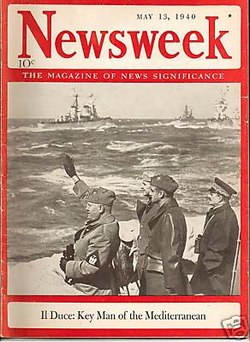

The principles of the doctrine of Fascism were laid down in an article by eminent philosopher Giovanni Gentile and Mussolini himself that appeared in 1932 in the Enciclopedia Italiana. Mussolini always portrayed himself as an intellectual, and some historians agree.[108] Gunther called him "easily the best educated and most sophisticated of the dictators", and the only national leader of 1940 who was an intellectual.[14] German historian Ernst Nolte said that "His command of contemporary philosophy and political literature was at least as great as that of any other contemporary European political leader."[109]

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Nationalists in the years after World War I thought of themselves as combating the liberal and domineering institutions created by cabinets—such as those of Giovanni Giolitti, including traditional schooling. Futurism, a revolutionary cultural movement which would serve as a catalyst for Fascism, argued for "a school for physical courage and patriotism", as expressed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1919. Marinetti expressed his disdain for "the by now prehistoric and troglodyte Ancient Greek and Latin courses", arguing for their replacement with exercise modelled on those of the Arditi soldiers. It was in those years that the first Fascist youth wings were formed: Avanguardia Giovanile Fascista (Fascist Youth Vanguards) in 1919, and Gruppi Universitari Fascisti (Fascist University Groups) in 1922.

After the March on Rome that brought Mussolini to power, the Fascists started considering ways to politicise Italian society, with an accent on education. Mussolini assigned former ardito and deputy-secretary for Education Renato Ricci the task of "reorganizing the youth from a moral and physical point of view". The Opera Nazionale Balilla was created through Mussolini's decree of 3 April 1926, and was led by Ricci for the following eleven years. It included children between the ages of 8 and 18, grouped as the Balilla and the Avanguardisti.

According to Mussolini: "Fascist education is moral, physical, social, and military: it aims to create a complete and harmoniously developed human, a fascist one according to our views". The "educational value set through action and example" was to replace the established approaches. Fascism opposed its version of idealism to prevalent rationalism, and used the Opera Nazionale Balilla to circumvent educational tradition by imposing the collective and hierarchy, as well as Mussolini's own personality cult.

Another important constituent of the Fascist cultural policy was Catholicism. In 1929, a concordat with the Vatican was signed, ending decades of struggle between the Italian state and the papacy that dated back to the 1870 takeover of the Papal States by the House of Savoy during the unification of Italy. The Lateran Treaty, by which the Italian state was at last recognised by the Catholic Church, and the independence of Vatican City was recognised by the Italian state, were so much appreciated by the ecclesiastic hierarchy that Pope Pius XI acclaimed Mussolini as "the Man of Providence".[110]

The 1929 treaty included a legal provision whereby the Italian government would protect the honour and dignity of the Pope by prosecuting offenders.[111] Mussolini had had his children baptised in 1923 and himself re-baptised by a Catholic priest in 1927.[112] After 1929, Mussolini, with his anti-communist doctrines, convinced many Catholics to actively support him.

Foreign policy

In foreign policy, Mussolini was pragmatic and opportunistic. His vision centered on forging a new Roman Empire in Africa and the Balkans, vindicating the so-called "mutilated victory" of 1918 imposed by Britain and France, which betrayed the Treaty of London and denied Italy its "natural right" to supremacy in the Mediterranean.[113][114] However, in the 1920s, given Germany's weakness, post-war reconstruction, and reparations issues, Europe's situation was unfavorable for openly revising the Treaty of Versailles. Italy's foreign policy focused on maintaining an "equidistant" stance from major powers to exercise "determinant weight," using alignment with one power to secure support for Italian ambitions in Europe and Africa.[115] Mussolini believed that Italy's population, then at 40 million, was insufficient for a major war, and sought to increase it to at least 60 million through relentless natalist policies, including making advocacy of contraception a criminal offense in 1924.[116][117]

Initially, Mussolini operated as a pragmatic statesman, seeking advantages without risking war with Britain and France. An exception was the 1923 Corfu incident, where Mussolini was prepared for war with Britain over the assassination of Italian military personnel, but was persuaded to accept a diplomatic solution by the Italian Navy's leadership.[118] In 1925, Mussolini secretly told Italian military leaders that Italy needed to win spazio vitale ('living space'), aiming to unite the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean under Italian control, though he acknowledged that Italy lacked sufficient manpower for war until the mid-1930s.[118] Mussolini participated in the Locarno Treaties of 1925, which guaranteed Germany's western borders. In 1929, he began planning for aggression against France and Yugoslavia, and by 1932 sought an anti-French alliance with Germany.[118] A planned attack on France and Yugoslavia in 1933 was aborted when Mussolini learned that French intelligence had broken Italian military codes.[118] After Adolf Hitler rose to power, threatening Italian interests in Austria and the Danube basin, Mussolini proposed the Four Power Pact with Britain, France, and Germany in 1933. Italy also signed the Italo-Soviet Pact[119] which was partly intended as a warning to Germany.[120] When Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss was assassinated in 1934 by Austrian Nazis during a coup, Mussolini threatened Hitler with war in the event of a German invasion of Austria, and opposed any German attempt at Anschluss, promoting the Stresa Front against Germany in 1935.

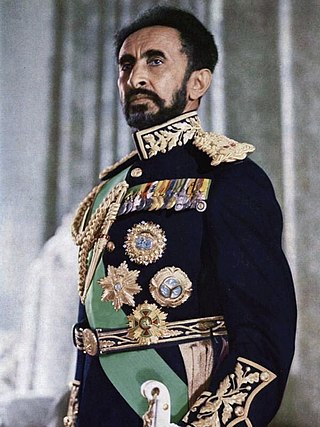

Despite earlier opposition to the Italo-Turkish War, after the Abyssinia Crisis of 1935–1936, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia following border incidents between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland. Historians are divided on the reasons for the invasion. Some argue it was a distraction from the Great Depression, while others see it as part of a broader expansionist program.[122] Italy’s forces quickly overwhelmed Ethiopia, leading to the proclamation of an Italian Empire in May 1936.[123] Confident of French support due to his opposition to Hitler, Mussolini dismissed the League of Nations' sanctions imposed over the Ethiopian invasion. He viewed the sanctions as hypocritical attempts by older imperial powers to block Italy’s expansion.[124][125] Italy was criticized for its use of mustard gas and brutal tactics against Ethiopian guerrillas.[123][126] Mussolini ordered systematic terror against Ethiopian rebels, targeting both combatants and civilians.[127][128] Mussolini ordered the execution of the entire adult male population in a town and in one district ordered that "the prisoners, their accomplices and the uncertain will have to be executed" as part of the "gradual liquidation" of the population.[127] Mussolini favoured a policy of brutality partly because he believed the Ethiopians were not a nation because black people were too stupid to have a sense of nationality.[128] The other reason was because Mussolini was planning on bringing millions of Italians into Ethiopia and wanted to kill off much of the population to make room.[128]

Sanctions against Italy pushed Mussolini towards an alliance with Germany. In 1936, he told the German Ambassador that Italy had no objections to Austria becoming a German satellite, removing a key obstacle to Italo-German relations.[129] After the sanctions ended, France and Britain tried to revive the Stresa Front, seeking to retain Italy as an ally. However, in 1936, Mussolini agreed to the Rome-Berlin Axis with Germany, and in 1939 signed the Pact of Steel, binding Italy and Germany in a full military alliance.

The conquest of Ethiopia cost 12,000 Italian lives and placed a severe financial burden on Italy. Mussolini had underestimated the cost of the invasion, which proved far higher than expected, and the ongoing occupation further strained Italy’s economy. The Ethiopian and Spanish wars consumed funds intended for military modernization, weakening Italy's military power.[130] From 1936 to 1939, Mussolini provided substantial military support to Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, further distancing Italy from France and Britain. This intervention and the worsening relationship with the Western powers led Mussolini to accept the German annexation of Austria and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. At the Munich Conference in 1938, Mussolini posed as a peacemaker while supporting Germany’s annexation of the Sudetenland.

In 1938, TIGR, a Slovene partisan group, plotted to assassinate Mussolini in Kobarid, but their attempt was unsuccessful.

Remove ads

World War II

Summarize

Perspective

Gathering storm

By the late 1930s, Mussolini concluded that Britain and France were declining powers, and that Germany and Italy, due to their demographic strength, were destined to rule Europe.[131] He believed that the declining birth rates in France were "absolutely horrifying" and that the British Empire was doomed because one-quarter of the British population was over 50.[131] Mussolini preferred an alliance with Germany over Britain and France, viewing it as better to be allied with the strong instead of the weak.[132] He saw international relations as a Social Darwinian struggle between "virile" nations with high birth rates destined to destroy "effete" nations with low birth rates. Mussolini had no interest in an alliance with France, which he considered a "weak and old" nation due to its declining birthrate.[133]

Mussolini's belief in Italy's destino to rule the Mediterranean led him to neglect serious planning for a war with the Western powers.[134] He was held back from full alignment with Berlin by Italy's economic and military unpreparedness and his desire to use the Easter Accords of April 1938 to split Britain from France.[135] A military alliance with Germany, rather than the looser political alliance under the Anti-Comintern Pact, would end any chance of Britain implementing the Easter Accords.[136] The Easter Accords were intended by Mussolini to allow Italy to take on France alone, with the hope that improved Anglo-Italian relations would keep Britain neutral in a Franco-Italian war (Mussolini had designs on Tunisia and some support in that country).[136] Britain, in turn, hoped the Easter Accords would win Italy away from Germany.

Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law and foreign minister, summed up the dictator's objectives regarding France in his diary on 8 November 1938: Djibouti would be ruled jointly with France; Tunisia with a similar regime; and Corsica under Italian control.[137] Mussolini showed no interest in Savoy, considering it neither "historically nor geographically Italian." On 30 November 1938, Mussolini provoked the French by orchestrating demonstrations where deputies demanded France turn over Tunisia, Savoy, and Corsica to Italy.[138] This led to heightened tensions, with France and Italy on the verge of war through the winter of 1938–39.[139]

In January 1939, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain visited Rome. Mussolini learned that while Britain wanted better relations with Italy, it would not sever ties with France.[140] This realization led Mussolini to grow more interested in the German offer of a military alliance, first made in May 1938.[140] In February 1939, Mussolini declared that a state's power is "proportional to its maritime position," asserting that Italy was a "prisoner in the Mediterranean," surrounded by British-controlled territories.[141]

The new pro-German course was controversial. On 21 March 1939, during a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council, Italo Balbo accused Mussolini of "licking Hitler's boots" and criticized the pro-German policy as leading Italy to disaster.[142] Despite some internal opposition, Mussolini's control of foreign policy ensured that dissenting voices had little impact.[142] In April 1939, Mussolini ordered the Italian invasion of Albania, quickly occupying the country and forcing King Zog I to flee.[143] In May 1939, Mussolini signed the Pact of Steel, a full military alliance with Germany, after securing a promise from Hitler that there would be no war for three years.

Despite the pact, Mussolini was cautious. When Hitler expressed his intent to invade Poland, Ciano warned that this would likely lead to war with the Allies. Hitler dismissed the warning, suggesting Italy should invade Yugoslavia.[144] Although tempted, Mussolini knew that Italy was unprepared for a global conflict, particularly given King Victor Emmanuel III's demand for neutrality.[144] Thus, when World War II began with Germany’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, Italy remained uninvolved.[144] However, when the Germans arrested 183 professors from Jagiellonian University in Kraków in November 1939, Mussolini intervened personally, resulting in the release of 101 Poles.[145]

War declared

As World War II began, Ciano and Viscount Halifax were holding secret phone conversations. The British wanted Italy on their side against Germany as it had been in World War I.[144] French government opinion was more geared towards action against Italy, as they were eager to attack Italy in Libya. In September 1939, France swung to the opposite extreme, offering to discuss issues with Italy, but as the French were unwilling to discuss Corsica, Nice and Savoy, Mussolini did not answer.[144] Mussolini's Under-Secretary for War Production, Carlo Favagrossa, had estimated that Italy could not be prepared for major military operations until 1942 due to its relatively weak industrial sector compared to western Europe.[146] In late November 1939, Adolf Hitler declared: "So long as the Duce lives, one can rest assured that Italy will seize every opportunity to achieve its imperialistic aims."[144]

Convinced that the war would soon be over, with a German victory looking likely at that point, Mussolini decided to enter the war on the Axis side. Accordingly, Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940. At 6 p.m., Benito Mussolini appeared on the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia to announce that in six hours, Italy would be in a state of war with France and Britain. After a speech explaining his motives for the decision, he concluded: "People of Italy: take up your weapons and show your tenacity, your courage and your valor."[23] The Italians had no battle plans of any kind prepared. This caused FDR to say that "On this tenth day of June 1940, the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor." Mussolini regarded the war against Britain and France as a life-or-death struggle between opposing ideologies—fascism and the "plutocratic and reactionary democracies of the west"—describing the war as "the struggle of the fertile and young people against the sterile people moving to the sunset; it is the struggle between two centuries and two ideas".[147]

Italy joined the Germans in the Battle of France, by launching the Italian invasion of France just beyond the border. Just eleven days later, France and Germany signed an armistice and on 24 June, Italy and France signed the Franco-Italian Armistice. Included in Italian-controlled France were most of Nice and other southeastern counties.[148] Mussolini planned to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of the UK in the European theatre. The Italians invaded Egypt, bombed Mandatory Palestine, and attacked the British in their Sudan, Kenya and British Somaliland colonies (in what would become known as the East African Campaign);[149] British Somaliland was conquered and became part of Italian East Africa on 3 August 1940, and there were Italian advances in the Sudan and Kenya with initial success.[150] The British government refused to accept proposals for a peace that would involve accepting Axis victories in Europe; plans for an invasion of the UK did not proceed and the war continued.

Path to defeat

In September 1940, the Italian Tenth Army was commanded by Marshal Rodolfo Graziani and crossed from Italian Libya into Egypt, where British forces were located; this would become the Western Desert Campaign. Advances were successful, but the Italians stopped at Sidi Barrani waiting for logistic supplies to catch up. On 24 October 1940, Mussolini sent the Italian Air Corps to Belgium, where it took part in the Blitz until January 1941.[151] In October, Mussolini also sent Italian forces into Greece, starting the Greco-Italian War. The Royal Air Force prevented the Italian invasion and allowed the Greeks to push the Italians back to Albania, but the Greek counter-offensive in Italian Albania ended in a stalemate.[152]

Events in Africa had changed by early 1941 as Operation Compass had forced the Italians back into Libya, causing high losses in the Italian Army.[153] Also in the East African Campaign, an attack was mounted against Italian forces. Despite putting up stiff resistance, they were overwhelmed at the Battle of Keren, and the Italian defence started to crumble with a final defeat in the Battle of Gondar. When addressing the Italian public on the events, Mussolini was open about the situation, saying "We call bread bread and wine wine, and when the enemy wins a battle it is useless and ridiculous to seek, as the English do in their incomparable hypocrisy, to deny or diminish it."[154] With the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece, Italy annexed Ljubljana, Dalmatia and Montenegro, and established the puppet states of Croatia and the Hellenic State.

General Mario Robotti, Commander of the Italian XI Corps in Slovenia and Croatia, issued an order in line with a directive received from Mussolini in June 1942: "I would not be opposed to all (sic) Slovenes being imprisoned and replaced by Italians. In other words, we should take steps to ensure that political and ethnic frontiers coincide".[155]

Mussolini first learned of Operation Barbarossa after the invasion of the Soviet Union had begun on 22 June 1941, and was not asked by Hitler to involve himself.[156] On 25 June 1941, he inspected the first units at Verona, which served as his launching pad to Russia.[157] Mussolini told the Council of Ministers of 5 July that his only worry was that Germany might defeat the Soviet Union before the Italians arrived.[158] At a meeting with Hitler in August, Mussolini offered and Hitler accepted the commitment of further Italian troops to fight the Soviet Union.[159] The heavy losses suffered by the Italians on the Eastern Front, where service was extremely unpopular owing to the widespread view that this was not Italy's fight, did much to damage Mussolini's prestige with the Italian people.[159] After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941.[160][161] A piece of evidence regarding Mussolini's response to the attack on Pearl Harbor comes from the diary of his Foreign Minister Ciano:

A night telephone call from Ribbentrop. He is overjoyed about the Japanese attack on America. He is so happy about it that I am happy with him, though I am not too sure about the final advantages of what has happened. One thing is now certain, that America will enter the conflict and that the conflict will be so long that she will be able to realize all her potential forces. This morning I told this to the King who had been pleased about the event. He ended by admitting that, in the long run, I may be right. Mussolini was happy, too. For a long time he has favored a definite clarification of relations between America and the Axis.[162]

Italian forces had achieved some success in the regions of Italian-occupied Balkans by suppressing partisan insurgency in Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania and in Montenegro. In 1942, Italy saw its greatest extent, as the Italian Regia Marina had controlled most of the Mediterranean Sea. In North Africa, together with German forces, Italian forces would drive the British forces out of Libya during the Battle of Gazala. They subsequently pushed towards Egypt with the aim of capturing Alexandria and the Suez Canal, but the offensive was halted at El Alamein in the summer of 1942. In October 1942, the Italian forces were severely defeated at the Second Battle of El Alamein by the British and Commonwealth forces and were driven out of Egypt. The British and Commonwealth forces would continue to push back the Italians until January 1943, when Italian Libya fell to the Allies.

Following Vichy France's collapse and the Case Anton in November 1942, Italy occupied the French territories of Corsica and Tunisia. Italian forces would use Tunisia as a base of military operations for the Tunisian campaign. Although Mussolini was aware that Italy, whose resources were reduced by the campaigns of the 1930s, was not ready for a long war, he opted to remain in the conflict to not abandon the occupied territories and the fascist imperial ambitions.[163]

Dismissal and arrest

By 1943, Italy's military position had become untenable. Axis forces in North Africa were defeated in the Tunisian Campaign in early 1943. Italy suffered major setbacks on the Eastern Front and in the Allied invasion of Sicily.[164] The Italian home front was also in bad shape as the Allied bombings were taking their toll. Factories all over Italy were brought to a virtual standstill because raw materials were lacking. There was a chronic shortage of food, and what food was available was being sold at nearly confiscatory prices. Mussolini's once-ubiquitous propaganda machine lost its grip on the people; a large number of Italians turned to Vatican Radio or Radio London for more accurate news coverage. Discontent came to a head in March 1943 with a wave of labour strikes in the industrial north—the first large-scale strikes since 1925.[165] Also in March, some of the major factories in Milan and Turin stopped production to secure evacuation allowances for workers' families. The German presence in Italy had sharply turned public opinion against Mussolini; when the Allies invaded Sicily, the majority of the public there welcomed them as liberators.[166]

Mussolini feared that with Allied victory in North Africa, Allied armies would come across the Mediterranean and attack Italy. In April 1943, as the Allies closed into Tunisia, Mussolini had urged Hitler to make a separate peace with the USSR and send German troops to the west to guard against an expected Allied invasion of Italy. The Allies landed in Sicily on 10 July 1943, and within a few days it was obvious the Italian army was on the brink of collapse. This led Hitler to summon Mussolini to a meeting in Feltre on 19 July 1943. By this time, Mussolini was so shaken from stress that he could no longer stand Hitler's boasting. His mood darkened further when that same day, the Allies bombed Rome—the first time that city had ever been the target of enemy bombing.[167] It was obvious by this time that the war was lost, but Mussolini could not extricate himself from the German alliance.[168] By this point, some prominent members of Mussolini's government had turned against him, including Grandi and Ciano. Several of his colleagues were close to revolt, and Mussolini was forced to summon the Grand Council on 24 July 1943. This was the first time the body had met since the start of the war. When he announced that the Germans were thinking of evacuating the south, Grandi launched a blistering attack on him.[164] Grandi moved a resolution asking the king to resume his full constitutional powers—in effect, a vote of no confidence in Mussolini. This motion carried by a 19–8 margin.[165] Mussolini showed little visible reaction, even though this effectively authorised the king to sack him. He did, however, ask Grandi to consider the possibility that this motion would spell the end of Fascism. The vote, although significant, had no de jure effect, since in Italy's constitutional monarchy the prime minister was responsible only to the king and only the king could dismiss the prime minister.[168]

Despite this sharp rebuke, Mussolini showed up for work the next day as usual. He allegedly viewed the Grand Council as merely an advisory body and did not think the vote would have any substantive effect.[165] That afternoon, at 17:00, he was summoned to the royal palace by Victor Emmanuel. By then, Victor Emmanuel had already decided to sack him; the king had arranged an escort for Mussolini and had the government building surrounded by 200 carabinieri. Mussolini was unaware of these moves by the king and tried to tell him about the Grand Council meeting. Victor Emmanuel cut him off and formally dismissed him from office, although guaranteeing his immunity.[165] After Mussolini left the palace, he was arrested by the carabinieri on the king's orders without telling him that he was formally arrested but rather under protective custody, as Victor Emmanuel III was trying to save the monarchy. The police took Mussolini in a Red Cross ambulance car, without specifying his destination and assuring him that they were doing it for his own safety.[169] By this time, discontent with Mussolini was so intense that when the news of his downfall was announced on the radio, there was no resistance of any sort. People rejoiced because they believed that the end of Mussolini also meant the end of the war.[165] The king appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio as the prime minister.

In an effort to conceal his location from the Germans, Mussolini was moved around: first to Ponza, then to La Maddalena, before being imprisoned at Campo Imperatore, a mountain resort in Abruzzo where he was completely isolated. Badoglio kept up the appearance of loyalty to Germany, and announced that Italy would continue fighting on the side of the Axis. However, he dissolved the Fascist Party two days after taking over and began negotiating with the Allies. On 3 September 1943, Badoglio agreed to an Armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces. Its announcement five days later threw Italy into chaos; German troops seized control in Operation Achse. As the Germans approached Rome, Badoglio and the king fled with their main collaborators to Apulia, putting themselves under the protection of the Allies, but leaving the Italian Army without orders.[170] After a period of anarchy, they formed a government in Malta, and finally declared war on Germany on 13 October 1943. Several thousand Italian troops joined the Allies to fight against the Germans; most others deserted or surrendered to the Germans; some refused to switch sides and joined the Germans. The Badoglio government agreed to a political truce with the predominantly leftist Partisans for the sake of Italy and to rid the land of the Nazis.[171]

Italian Social Republic ("Salò Republic")

Italian Social Republic (RSI) as of 1943

Only two months after Mussolini had been dismissed and arrested, he was rescued from his prison at the Hotel Campo Imperatore in the Gran Sasso raid on 12 September 1943 by a special Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) unit and Waffen-SS commandos led by Major Otto-Harald Mors; Otto Skorzeny was also present.[169] The rescue saved Mussolini from being turned over to the Allies in accordance with the armistice.[171] Hitler had made plans to arrest the king, the Crown Prince Umberto, Badoglio, and the rest of the government and restore Mussolini to power in Rome, but the government's escape south likely foiled those plans.[172]

Three days after his rescue in the Gran Sasso raid, Mussolini was taken to Germany for a meeting with Hitler in Rastenburg at his East Prussian headquarters. Despite his public support, Hitler was clearly shocked by Mussolini's dishevelled and haggard appearance as well as his unwillingness to go after the men in Rome who overthrew him. Feeling that he had to do what he could to blunt the edges of Nazi repression, Mussolini agreed to set up a new regime, the Italian Social Republic (Italian: Repubblica Sociale Italiana, RSI),[164] informally known as the Salò Republic because of its seat in the town of Salò, where he was settled 11 days after his rescue by the Germans. His new regime was much reduced in territory; in addition to losing the Italian lands held by the Allies and Badoglio's government, the provinces of Bolzano, Belluno and Trento were placed under German administration in the Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills, while the provinces of Udine, Gorizia, Trieste, Pola (now Pula), Fiume (now Rijeka), and Ljubljana (Lubiana in Italian) were incorporated into the German Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral.[173][174]

Additionally, German forces occupied the Dalmatian provinces of Split (Spalato) and Kotor (Cattaro), which were subsequently annexed by the Croatian fascist regime. Italy's conquests in Greece and Albania were also lost to Germany, with the exception of the Italian Islands of the Aegean, which remained nominally under RSI rule.[175] Mussolini opposed any territorial reductions of the Italian state and told his associates:

I am not here to renounce even a square meter of state territory. We will go back to war for this. And we will rebel against anyone for this. Where the Italian flag flew, the Italian flag will return. And where it has not been lowered, now that I am here, no one will have it lowered. I have said these things to the Führer.[176]

For about a year and a half, Mussolini lived in Gargnano on Lake Garda in Lombardy. Although he insisted in public that he was in full control, he knew he was a puppet ruler under the protection of his German liberators—for all intents and purposes, the Gauleiter of Lombardy.[177] Indeed, he lived under what amounted to house arrest by the SS, who restricted his communications and travel. He told one of his colleagues that being sent to a concentration camp would be preferable.[168]

Yielding to pressure from Hitler and the remaining loyal fascists who formed the government of the Republic of Salò, Mussolini helped orchestrate executions of some of the leaders who had betrayed him at the last meeting of the Fascist Grand Council. One of those executed was his son-in-law, Galeazzo Ciano. As head of state and Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Italian Social Republic, Mussolini used much of his time to write his memoirs. Along with his autobiographical writings of 1928, these writings would be combined and published by Da Capo Press as My Rise and Fall. In an interview in January 1945 by Madeleine Mollier, a few months before he was captured and executed, he stated flatly: "Seven years ago, I was an interesting person. Now, I am little more than a corpse." He continued: