Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Berbers

Ethnic group indigenous to North Africa From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Berbers, or the Berber peoples,[a] also known as Amazigh[b] or Imazighen,[c] are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arabs in the Maghreb.[38][39][40][41] Their main connections are identified by their usage of Berber languages, most of them mutually unintelligible,[40][42] which are part of the Afroasiatic language family.

This article has an unclear citation style. (December 2022) |

They are indigenous to the Maghreb region of North Africa, where they live in scattered communities across parts of Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and to a lesser extent Tunisia, Mauritania, northern Mali and northern Niger (Azawagh).[41][43][44] Smaller Berber communities are also found in Burkina Faso and Egypt's Siwa Oasis.[45][46][47]

Descended from Stone Age tribes of North Africa, accounts of the Imazighen were first mentioned in Ancient Egyptian writings.[48][49] From about 2000 BC, Berber languages spread westward from the Nile Valley across the northern Sahara into the Maghreb. A series of Berber peoples such as the Mauri, Masaesyli, Massyli, Musulamii, Gaetuli, and Garamantes gave rise to Berber kingdoms, such as Numidia and Mauretania. Other kingdoms appeared in late antiquity, such as Altava, Aurès, Ouarsenis, and Hodna.[50] Berber kingdoms were eventually suppressed by the Arab conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries AD. This started a process of cultural and linguistic assimilation known as Arabization, which influenced the Berber population. Arabization involved the spread of Arabic language and Arab culture among the Berbers, leading to the adoption of Arabic as the primary language and conversion to Islam. Notably, the Arab migrations to the Maghreb from the 7th century to the 17th century accelerated this process.[51] Berber tribes remained powerful political forces and founded new ruling dynasties in the 10th and 11th centuries, such as the Zirids, Hammadids, various Zenata principalities in the western Maghreb, and several Taifa kingdoms in al-Andalus, and empires of the Almoravids and Almohads. Their Berber successors – the Marinids, the Zayyanids, and the Hafsids – continued to rule until the 16th century. From the 16th century onward, the process continued in the absence of Berber dynasties; in Morocco, they were replaced by Arabs claiming descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[50]

Berbers are divided into several diverse ethnic groups and Berber languages, such as Kabyles, Chaouis and Rifians. Historically, Berbers across the region did not see themselves as a single cultural or linguistic unit, nor was there a greater "Berber community", due to their differing cultures.[52] They also did not refer to themselves as Berbers/Amazigh but had their own terms to refer to their own groups and communities.[53] They started being referred to collectively as Berbers after the Arab conquests of the 7th century and this distinction was revived by French colonial administrators in the 19th century. Today, the term "Berber" is viewed as pejorative by many who prefer the term "Amazigh".[54] Since the late 20th century, a trans-national movement – known as Berberism or the Berber Culture Movement – has emerged among various parts of the Berber populations of North Africa to promote a collective Amazigh ethnic identity and to militate for greater linguistic rights and cultural recognition.[55]

Remove ads

Names and etymology

Summarize

Perspective

The indigenous populations of the Maghreb region of North Africa are collectively known as Berbers or Amazigh in English.[41]

Tribal titles such as Barabara and Beraberata appear in Egyptian inscriptions of 1700 and 1300 BC, and the Berbers were probably intimately related with the Egyptians in very early times. Thus the true ethnic name may have become confused with Barbari, the designation used by classical conquerors.[56][better source needed]

The plural form Imazighen is sometimes also used in English.[43][57] While Berber is more widely known among English-speakers, its usage is a subject of debate, due to its historical background as an exonym and present equivalence with the Arabic word for "barbarian".[58][59][44][60] Historically, Berbers did not refer to themselves as Berbers/Amazigh but had their own terms to refer to themselves. For example, the Kabyle use the term "Leqbayel" to refer to their own people, while the Chaoui identified as "Ishawiyen", instead of Berber/Amazigh.[53]

Stéphane Gsell proposed the translation "noble/free" for the term Amazigh based on Leo Africanus's translation of "awal amazigh" as "noble language" referring to the Berber languages; this definition remains disputed and is largely seen as an undue extrapolation.[61][62][63] The term Amazigh also has a cognate in the Tuareg "Amajegh", meaning noble.[64][61] "Mazigh" was used as a tribal surname in Roman Mauretania Caesariensis.[62][65]

Abraham Isaac Laredo proposes that the term Amazigh could be derived from "Mezeg", which is the name of Dedan of Sheba in the Targum.[66][61]

The medieval Arab historian Ibn Khaldun says the Berbers were descendants of Barbar, the son of Tamalla, son of Mazigh, son of Canaan, son of Ham, son of Noah.[67][61]

The Numidian, Mauri and Libu populations of antiquity are typically understood by contemporary writers to have referred to approximately the same population as modern Berbers.[68][69]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The areas of North Africa that have retained the Berber language and traditions best have been, in general, Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Much of Berber culture is still celebrated among the cultural elite in Morocco and Algeria, especially in Kabylia, the Aurès and the Atlas Mountains. The Kabyles were one of the few peoples in North Africa who remained independent during successive rule by the Carthaginians, Romans, Byzantines, Vandals, and the Ottoman Turks.[70][71][72][73] Even after the Arab conquest of North Africa, the Kabyle people still maintained possession of their mountains.[74][75]

Prehistory

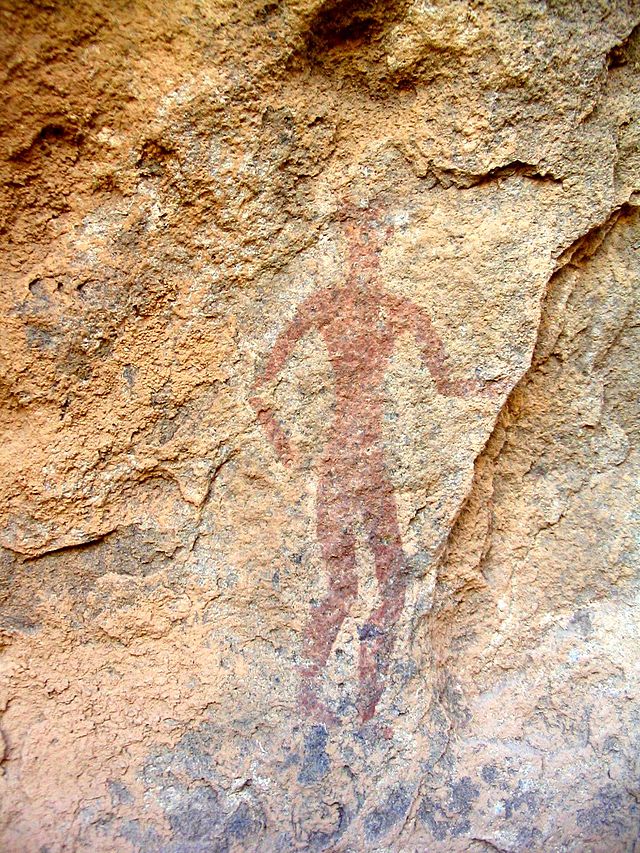

The Maghreb region in northwestern Africa is believed to have been inhabited by Berbers from at least 10,000 BC.[76] Cave paintings, which have been dated to twelve millennia before present, have been found in the Tassili n'Ajjer region of southeastern Algeria. Other rock art has been discovered at Tadrart Acacus in the Libyan desert. A Neolithic society, marked by domestication and subsistence agriculture and richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer paintings, developed and predominated in the Saharan and Mediterranean region (the Maghreb) of northern Africa between 6000 and 2000 BC (until the classical period).

Prehistoric Tifinagh inscriptions were found in the Oran region.[77] During the pre-Roman era, several successive independent states (Massylii) existed before King Masinissa unified the people of Numidia.[78][79][80][full citation needed]

Mythology

According to the Roman historian Gaius Sallustius Crispus, the original people of North Africa are the Gaetulians and the Libyans, they were the prehistoric peoples that crossed to Africa from the Iberian Peninsula, then much later, Hercules and his army crossed from Iberia to North Africa where his army intermarried with the local populace and settled the region permanently, the Medes of his army that married the Libyans formed the Maur people, while the other part of his Army formed the Nomadas or as they are today known as the Numidians which later on united all of Berber tribes of North Africa under the rule of Massinissa.

Other sources

According to the Al-Fiḥrist, the Barber (i.e. Berbers) comprised one of seven principal races in Africa.[81]

The medieval Tunisian scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), recounting the oral traditions prevalent in his day, sets down two popular opinions as to the origin of the Berbers: according to one opinion, they are descended from Canaan, son of Ham, and have for ancestors Berber, son of Temla, son of Mazîgh, son of Canaan, son of Ham, a son of Noah;[82] alternatively, Abou-Bekr Mohammed es-Souli (947 AD) held that they are descended from Berber, the son of Keloudjm (Casluhim), the son of Mesraim, the son of Ham.[82]

They belong to a powerful, formidable, brave and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen – like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans. The men who belong to this family of peoples have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.

— Ibn Khaldun[83]

Ancestry and DNA

As of about 5000 BC, the populations of North Africa were descended primarily from the Iberomaurusian and Capsian cultures, with a more recent intrusion being associated with the Neolithic Revolution.[84] The proto-Berber tribes evolved from these prehistoric communities during the late Bronze- and early Iron ages.[85]

Uniparental DNA analysis has established ties between Berbers and other Afroasiatic speakers in Africa. Most of these populations belong to the E1b1b paternal haplogroup, with Berber speakers having among the highest frequencies of this lineage.[86]

Additionally, genomic analysis found that Berber and other Maghreb communities have a high frequency of an ancestral component that originated in the Near East. This Maghrebi element peaks among Tunisian Berbers.[87] This ancestry is related to the Coptic/Ethio-Somali component, which diverged from these and other West Eurasian-affiliated components before the Holocene.[88]

In 2013, Iberomaurusian skeletons from the prehistoric sites of Taforalt and Afalou in the Maghreb were also analyzed for ancient DNA. All of the specimens belonged to maternal clades associated with either North Africa or the northern and southern Mediterranean littoral, indicating gene flow between these areas since the Epipaleolithic.[89] The ancient Taforalt individuals carried the mtDNA haplogroups U6, H, JT, and V, which points to population continuity in the region dating from the Iberomaurusian period.[90]

Human fossils excavated at the Ifri n'Amr ou Moussa site in Morocco have been radiocarbon dated to the Early Neolithic period, c. 5000 BC. Ancient DNA analysis of these specimens indicates that they carried paternal haplotypes related to the E1b1b1b1a (E-M81) subclade and the maternal haplogroups U6a and M1, all of which are frequent among present-day communities in the Maghreb. These ancient individuals also bore an autochthonous Maghrebi genomic component that peaks among modern Berbers, indicating that they were ancestral to populations in the area. Additionally, fossils excavated at the Kelif el Boroud site near Rabat were found to carry the broadly distributed paternal haplogroup T-M184 as well as the maternal haplogroups K1, T2 and X2, the latter of which were common mtDNA lineages in Neolithic Europe and Anatolia. These ancient individuals likewise bore the Berber-associated Maghrebi genomic component. This altogether indicates that the late-Neolithic Kehf el Baroud inhabitants were ancestral to contemporary populations in the area, but also likely experienced gene flow from Europe.[91]

The late-Neolithic Kehf el Baroud inhabitants were modelled as being of about 50% local North African ancestry and 50% Early European Farmer (EEF) ancestry. It was suggested that EEF ancestry had entered North Africa through Cardial Ware colonists from Iberia sometime between 5000 and 3000 BC. They were found to be closely related to the Guanches of the Canary Islands. The authors of the study suggested that the Berbers of Morocco carried a substantial amount of EEF ancestry before the establishment of Roman colonies in Berber Africa.[91]

Antiquity

The great tribes of Berbers in classical antiquity (when they were often known as ancient Libyans)[92][d] were said to be three (roughly, from west to east): the Mauri, the Numidians near Carthage, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauretania, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians occupied the regions between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both the Mauri and the Numidians had significant sedentary populations living in villages, and their peoples both tilled the land and tended herds. The Gaetulians lived to the near south, on the northern margins of the Sahara, and were less settled, with predominantly pastoral elements.[93][94][95]: 41f

For their part, the Phoenicians (Semitic-speaking Canaanites) came from perhaps the most advanced multicultural sphere then existing, the western coast of the Fertile Crescent region of West Asia. Accordingly, the material culture of Phoenicia was likely more functional and efficient, and their knowledge more advanced, than that of the early Berbers. Hence, the interactions between Berbers and Phoenicians were often asymmetrical. The Phoenicians worked to keep their cultural cohesion and ethnic solidarity, and continuously refreshed their close connection with Tyre, the mother city.[92]: 37

The earliest Phoenician coastal outposts were probably meant merely to resupply and service ships bound for the lucrative metals trade with the Iberians,[96] and perhaps at first regarded trade with the Berbers as unprofitable.[97] However, the Phoenicians eventually established strategic colonial cities in many Berber areas, including sites outside of present-day Tunisia, such as the settlements at Oea, Leptis Magna, Sabratha (in Libya), Volubilis, Chellah, and Mogador (now in Morocco). As in Tunisia, these centres were trading hubs, and later offered support for resource development, such as processing olive oil at Volubilis and Tyrian purple dye at Mogador. For their part, most Berbers maintained their independence as farmers or semi-pastorals, although, due to the example of Carthage, their organized politics increased in scope and sophistication.[95]

In fact, for a time their numerical and military superiority (the best horse riders of that time) enabled some Berber kingdoms to impose a tribute on Carthage, a condition that continued into the 5th century BC.[96]: 64–65 Also, due to the Berbero-Libyan Meshwesh dynasty's rule of Egypt (945–715 BC),[98] the Berbers near Carthage commanded significant respect (yet probably appearing more rustic than the elegant Libyan pharaohs on the Nile). Correspondingly, in early Carthage, careful attention was given to securing the most favourable treaties with the Berber chieftains, "which included intermarriage between them and the Punic aristocracy".[99] In this regard, perhaps the legend about Dido, the foundress of Carthage, as related by Trogus is apposite. Her refusal to wed the Mauritani chieftain Hiarbus might be indicative of the complexity of the politics involved.[100]

Eventually, the Phoenician trading stations would evolve into permanent settlements, and later into small towns, which would presumably require a wide variety of goods as well as sources of food, which could be satisfied through trade with the Berbers. Yet, here too, the Phoenicians probably would be drawn into organizing and directing such local trade, and also into managing agricultural production. In the 5th century BC, Carthage expanded its territory, acquiring Cape Bon and the fertile Wadi Majardah,[101] later establishing control over productive farmlands for several hundred kilometres.[102] Appropriation of such wealth in land by the Phoenicians would surely provoke some resistance from the Berbers; although in warfare, too, the technical training, social organization, and weaponry of the Phoenicians would seem to work against the tribal Berbers. This social-cultural interaction in early Carthage has been summarily described:

Lack of contemporary written records makes the drawing of conclusions here uncertain, which can only be based on inference and reasonable conjecture about matters of social nuance. Yet it appears that the Phoenicians generally did not interact with the Berbers as economic equals, but employed their agricultural labour, and their household services, whether by hire or indenture; many became sharecroppers.[92]: 86

For a period, the Berbers were in constant revolt, and in 396 there was a great uprising.

Thousands of rebels streamed down from the mountains and invaded Punic territory, carrying the serfs of the countryside along with them. The Carthaginians were obliged to withdraw within their walls and were besieged.

Yet the Berbers lacked cohesion; and although 200,000 strong at one point, they succumbed to hunger, their leaders were offered bribes, and "they gradually broke up and returned to their homes".[96]: 125, 172 Thereafter, "a series of revolts took place among the Libyans [Berbers] from the fourth century onwards".[92]: 81

The Berbers had become involuntary 'hosts' to the settlers from the east, and were obliged to accept the dominance of Carthage for centuries. Nonetheless, therein they persisted largely unassimilated,[citation needed] as a separate, submerged entity, as a culture of mostly passive urban and rural poor within the civil structures created by Punic rule.[103] In addition, and most importantly, the Berber peoples also formed quasi-independent satellite societies along the steppes of the frontier and beyond, where a minority continued as free 'tribal republics'. While benefiting from Punic material culture and political-military institutions, these peripheral Berbers (also called Libyans)—while maintaining their own identity, culture, and traditions—continued to develop their own agricultural skills and village societies, while living with the newcomers from the east in an asymmetric symbiosis.[e][105]

As the centuries passed, a society of Punic people of Phoenician descent but born in Africa, called Libyphoenicians emerged there. This term later came to be applied also to Berbers acculturated to urban Phoenician culture.[92]: 65, 84–86 Yet the whole notion of a Berber apprenticeship to the Punic civilization has been called an exaggeration sustained by a point of view fundamentally foreign to the Berbers.[94]: 52, 58 A population of mixed ancestry, Berber and Punic, evolved there, and there would develop recognized niches in which Berbers had proven their utility. For example, the Punic state began to field Berber–Numidian cavalry under their commanders on a regular basis. The Berbers eventually were required to provide soldiers (at first "unlikely" paid "except in booty"), which by the fourth century BC became "the largest single element in the Carthaginian army".[92]: 86

Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society.[citation needed] Thus, when the Greeks under Agathocles (361–289 BC) of Sicily landed at Cape Bon and threatened Carthage (in 310 BC), there were Berbers, under Ailymas, who went over to the invading Greeks.[96]: 172 [f] During the long Second Punic War (218–201 BC) with Rome (see below), the Berber King Masinissa (c. 240 – c. 148 BC) joined with the invading Roman general Scipio, resulting in the war-ending defeat of Carthage at Zama, despite the presence of their renowned general Hannibal; on the other hand, the Berber King Syphax (d. 202 BC) had supported Carthage. The Romans, too, read these cues, so that they cultivated their Berber alliances and, subsequently, favored the Berbers who advanced their interests following the Roman victory.[106]

Carthage was faulted by her ancient rivals for the "harsh treatment of her subjects" as well as for "greed and cruelty".[92]: 83 [g][107] Her Libyan Berber sharecroppers, for example, were required to pay half of their crops as tribute to the city-state during the emergency of the First Punic War. The normal exaction taken by Carthage was likely "an extremely burdensome" one-quarter.[92]: 80 Carthage once famously attempted to reduce the number of its Libyan and foreign soldiers, leading to the Mercenary War (240–237 BC).[96]: 203–209 [108][109] The city-state also seemed to reward those leaders known to deal ruthlessly with its subject peoples, hence the frequent Berber insurrections. Moderns fault Carthage for failure "to bind her subjects to herself, as Rome did [her Italians]", yet Rome and the Italians held far more in common perhaps than did Carthage and the Berbers. Nonetheless, a modern criticism is that the Carthaginians "did themselves a disservice" by failing to promote the common, shared quality of "life in a properly organized city" that inspires loyalty, particularly with regard to the Berbers.[92]: 86–87 Again, the tribute demanded by Carthage was onerous.[110]

[T]he most ruinous tribute was imposed and exacted with unsparing rigour from the subject native states, and no slight one either from the cognate Phoenician states. ... Hence arose that universal disaffection, or rather that deadly hatred, on the part of her foreign subjects, and even of the Phoenician dependencies, toward Carthage, on which every invader of Africa could safely count as his surest support. ... This was the fundamental, the ineradicable weakness of the Carthaginian Empire ...[110]

The Punic relationship with the majority of the Berbers continued throughout the life of Carthage. The unequal development of material culture and social organization perhaps fated the relationship to be an uneasy one. A long-term cause of Punic instability, there was no melding of the peoples. It remained a source of stress and a point of weakness for Carthage. Yet there were degrees of convergence on several particulars, discoveries of mutual advantage, occasions of friendship, and family.[111]

The Berbers gain historicity gradually during the Roman era. Byzantine authors mention the Mazikes (Amazigh) as tribal people raiding the monasteries of Cyrenaica. Garamantia was a notable Berber kingdom that flourished in the Fezzan area of modern-day Libya in the Sahara desert between 400 BC and 600 AD.

Roman-era Cyrenaica became a center of early Christianity. Some pre-Islamic Berbers were Christians[112] (there is a strong correlation between adherence to the Donatist doctrine and being a Berber, ascribed to the doctrine matching their culture, as well as their being alienated from the dominant Roman culture of the Catholic church),[83] some perhaps Jewish, and some adhered to their traditional polytheist religion. The Roman-era authors Apuleius and St. Augustine were born in Numidia, as were three popes, one of whom, Pope Victor I, served during the reign of Roman emperor Septimius Severus, who was a North African of Roman/Punic ancestry (perhaps with some Berber blood).[113]

Numidia

Numidia (202 – 46 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a Roman province and being a Roman client state. The kingdom was located on the eastern border of modern Algeria, bordered by the Roman province of Mauretania (in modern Algeria and Morocco) to the west, the Roman province of Africa (modern Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. Its people were the Numidians.

The name Numidia was first applied by Polybius and other historians during the third century BC to indicate the territory west of Carthage, including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha (Muluya), about 160 kilometres (100 mi) west of Oran. The Numidians were conceived of as two great groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii, under King Gala, were allied with Carthage, while the western Masaesyli, under King Syphax, were allied with Rome.

In 206 BC, the new king of the Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax, of the Masaesyli, switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war, the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa. At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of Carthaginian territory, and southeast as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage except towards the sea.[114]

Masinissa was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118 BC, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, of Berber origin, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarreled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.

After Jugurtha defeated him in open battle, Adherbal fled to Rome for help. The Roman officials, allegedly due to bribes but perhaps more likely out of a desire to quickly end conflict in a profitable client kingdom, sought to settle the quarrel by dividing Numidia into two parts. Jugurtha was assigned the western half. However, soon after, conflict broke out again, leading to the Jugurthine War between Rome and Numidia.

Mauretania

In antiquity, Mauretania (3rd century BC – 44 BC) was an ancient Mauri Berber kingdom in modern Morocco and part of Algeria. It became a client state of the Roman empire in 33 BC, after the death of king Bocchus II, then a full Roman province in AD 40, after the death of its last king, Ptolemy of Mauretania, a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Middle Ages

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches, Butr and Baranis (known also as Botr and Barnès), descended from Mazigh ancestors, who were themselves divided into tribes and subtribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several fully independent tribes (e.g., Sanhaja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmuda, Kutama, Awraba, Barghawata, etc.).[115][full citation needed][116]

The Mauro-Roman Kingdom was an independent Christian Berber kingdom centred in the capital city of Altava (present-day Algeria) which controlled much of the ancient Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis. Berber Christian communities within the Maghreb all but disappeared under Islamic rule. The indigenous Christian population in some Nefzaoua villages persisted until the 14th century.[117]

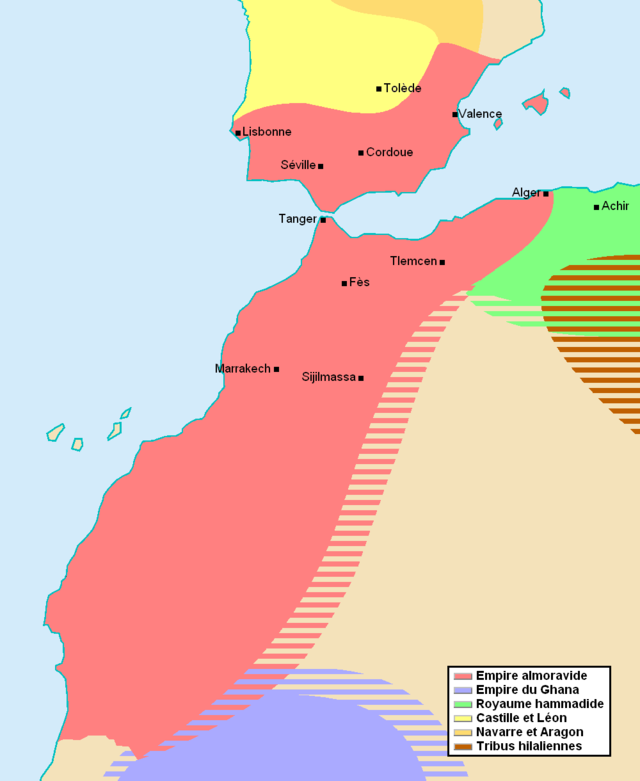

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb and al-Andalus. The most notable are the Zirids (Ifriqiya, 973–1148), the Hammadids (Western Ifriqiya, 1014–1152), the Almoravid dynasty (Morocco and al-Andalus, 1040–1147), the Almohads (Morocco and al-Andalus, 1147–1248), the Hafsids (Ifriqiya, 1229–1574), the Zianids (Tlemcen, 1235–1556), the Marinids (Morocco, 1248–1465) and the Wattasids (Morocco, 1471–1554).

Before the eleventh century, most of Northwest Africa had become a Berber-speaking Muslim area. Unlike the conquests of previous religions and cultures, the spread of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have extensive and long-lasting effects on the Maghreb. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of Berber society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms. A further Arabization of the region was in large part due to the arrival of the Banu Hilal, a tribe sent by the Fatimids of Egypt to punish the Berber Zirid dynasty for having abandoned Shiism. The Banu Hilal reduced the Zirids to a few coastal towns and took over much of the plains, resulting in the spread of nomadism to areas where agriculture had previously been dominant.

Besides the Arabian influence, North Africa also saw an influx, via the Barbary slave trade, of Europeans, with some estimates placing the number of European slaves brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period to be as high as 1.25 million.[118] Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, traders, and nomads from other parts of Africa also left impressions upon the Berber people.

Islamic conquest

The first Arabian military expeditions into the Maghreb, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. These early forays from a base in Egypt occurred under local initiative rather than under orders from the central caliphate. But when the seat of the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus, the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty ruling from 661 to 750) recognized that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. In 670, therefore, an Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi established the town of Qayrawan about 160 kilometres south of modern Tunis and used it as a base for further operations.

Abu al-Muhajir Dinar, Uqba's successor, pushed westward into Algeria and eventually worked out a modus vivendi with Kusaila, the ruler of an extensive confederation of Christian Berbers. Kusaila, who had been based in Tlemcen, became a Muslim and moved his headquarters to Takirwan, near Al Qayrawan. This harmony was short-lived; Arabian and Berber forces controlled the region in turn until 697. Umayyad forces conquered Carthage in 698, expelling the Byzantines, and in 703 decisively defeated Dihya's Berber coalition at the Battle of Tabarka. By 711, Umayyad forces helped by Berber converts to Islam had conquered all of North Africa. Governors appointed by the Umayyad caliphs ruled from Kairouan, capital of the new wilaya (province) of Ifriqiya, which covered Tripolitania (the western part of modern Libya), Tunisia, and eastern Algeria.

The spread of Islam among the Berbers did not guarantee their support for the Arab-dominated caliphate, due to the discriminatory attitude of the Arabs. The ruling Arabs alienated the Berbers by taxing them heavily, treating converts as second-class Muslims, and, worst of all, by enslaving them. As a result, widespread opposition took the form of open revolt in 739–740 under the banner of Ibadi Islam. The Ibadi had been fighting Umayyad rule in the East, and many Berbers were attracted by the sect's seemingly egalitarian precepts.

After the revolt, Ibadis established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. But others, such as Sijilmasa and Tlemcen, which straddled the principal trade routes, proved more viable and prospered. In 750, the Abbasids, who succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers, moved the caliphate to Baghdad and reestablished caliphal authority in Ifriqiya, appointing Ibrahim ibn al Aghlab as governor in Kairouan. Though nominally serving at the caliph's pleasure, Al Aghlab and his successors, the Aghlabids, ruled independently until 909, presiding over a court that became a center of learning and culture.

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustam ruled most of the central Maghreb from Tahert, south-west of Algiers. The rulers of the Rustamid imamate (761–909), each an Ibadi imam, were elected by leading citizens. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice. The court at Tahert was noted for its support of scholarship in mathematics, astronomy, astrology, theology, and law. The Rustamid imams failed, by choice or by neglect, to organize a reliable standing army. This important factor, accompanied by the dynasty's eventual collapse into decadence, opened the way for Tahert's demise under the assault of the Fatimids.

Mahdia was founded by the Fatimids under the Caliph Abdallah al-Mahdi in 921, and made the capital city of Ifriqiya by caliph Abdallah El Fatimi.[119] It was chosen as the capital because of its proximity to the sea, and the promontory on which an important military settlement had been since the time of the Phoenicians.[120]

In al-Andalus under the Umayyad governors

The Muslims who invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 711 were mainly Berbers, and were led by a Berber, Tariq ibn Ziyad, under the suzerainty of the Arab Caliph of Damascus Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan and his North African Viceroy, Musa ibn Nusayr.[121] Due to subsequent antagonism between Arabs and Berbers, and due to the fact that most of the histories of al-Andalus were written from an Arab perspective, the Berber role is understated in the available sources.[121] The biographical dictionary of Ibn Khallikan preserves the record of the Berber predominance in the invasion of 711, in the entry on Tariq ibn Ziyad.[121] A second mixed army of Arabs and Berbers came in 712 under Ibn Nusayr himself. They supposedly helped the Umayyad caliph Abd ar-Rahman I in al-Andalus, because his mother was a Berber.

English medievalist Roger Collins suggests that if the forces that invaded the Iberian peninsula were predominantly Berber, it is because there were insufficient Arab forces in Africa to maintain control of Africa and attack Iberia at the same time.[121]: 98 Thus, although north Africa had only been conquered about a dozen years previously, the Arabs already employed forces of the defeated Berbers to carry out their next invasion.[121]: 98 This would explain the predominance of Berbers over Arabs in the initial invasion. In addition, Collins argues that Berber social organization made it possible for the Arabs to recruit entire tribal units into their armies, making the defeated Berbers excellent military auxiliaries.[121]: 99 The Berber forces in the invasion of Iberia came from Ifriqiya or as far away as Tripolitania.[122]

Governor As-Samh distributed land to the conquering forces, apparently by tribe, though it is difficult to determine from the few historical sources available.[121]: 48–49 It was at this time that the positions of Arabs and Berbers were regularized across the Iberian peninsula. Berbers were positioned in many of the most mountainous regions of Spain, such as Granada, the Pyrenees, Cantabria, and Galicia. Collins suggests this may be because some Berbers were familiar with mountain terrain, whereas the Arabs were not.[121]: 49–50 By the late 710s, there was a Berber governor in Leon or Gijon.[121]: 149 When Pelagius revolted in Asturias, it was against a Berber governor. This revolt challenged As-Samh's plans to settle Berbers in the Galician and Cantabrian mountains, and by the middle of the eighth century it seems there was no more Berber presence in Galicia.[121]: 49–50 The expulsion of the Berber garrisons from central Asturias, following the battle of Covadonga, contributed to the eventual formation of the independent Asturian kingdom.[122]: 63

Many Berbers were settled in what were then the frontier lands near Toledo, Talavera, and Mérida,[121]: 195 Mérida becoming a major Berber stronghold in the eighth century.[121]: 201 The Berber garrison in Talavera would later be commanded by Amrus ibn Yusuf and was involved in military operations against rebels in Toledo in the late 700s and early 800s.[121]: 210 Berbers were also initially settled in the eastern Pyrenees and Catalonia.[121]: 88–89, 195 They were not settled in the major cities of the south, and were generally kept in the frontier zones away from Cordoba.[121]: 207

Roger Collins cites the work of Pierre Guichard to argue that Berber groups in Iberia retained their own distinctive social organization.[121]: 90 [123][124] According to this traditional view of Arab and Berber culture in the Iberian peninsula, Berber society was highly impermeable to outside influences, whereas Arabs became assimilated and Hispanized.[121]: 90 Some support for the view that Berbers assimilated less comes from an excavation of an Islamic cemetery in northern Spain, which reveals that the Berbers accompanying the initial invasion brought their families with them from north Africa.[122][125]

In 731, the eastern Pyrenees were under the control of Berber forces garrisoned in the major towns under the command of Munnuza. Munnuza attempted a Berber uprising against the Arabs in Spain, citing mistreatment of Berbers by Arabic judges in north Africa, and made an alliance with Duke Eudo of Aquitaine. However, governor Abd ar-Rahman attacked Munnuza before he was ready, and, besieging him, defeated him at Cerdanya. Because of the alliance with Munnuza, Abd ar-Rahman wanted to punish Eudo, and his punitive expedition ended in the Arab defeat at Poitiers.[121]: 88–90

By the time of the governor Uqba, and possibly as early as 714, the city of Pamplona was occupied by a Berber garrison.[121]: 205–206 An eighth-century cemetery has been discovered with 190 burials all according to Islamic custom, testifying to the presence of this garrison.[121]: 205–206 [126] In 798, however, Pamplona is recorded as being under a Banu Qasi governor, Mutarrif ibn Musa. Ibn Musa lost control of Pamplona to a popular uprising. In 806 Pamplona gave its allegiance to the Franks, and in 824 became the independent Kingdom of Pamplona. These events put an end to the Berber garrison in Pamplona.[121]: 206–208

Medieval Egyptian historian Al-Hakam wrote that there was a major Berber revolt in north Africa in 740–741, led by Masayra. The Chronicle of 754 calls these rebels Arures, which Collins translates as 'heretics', arguing it is a reference to the Berber rebels' Ibadi or Khariji sympathies.[121]: 107 After Charles Martel attacked Arab ally Maurontus at Marseille in 739, governor Uqba planned a punitive attack against the Franks, but news of a Berber revolt in north Africa made him turn back when he reached Zaragoza.[121]: 92 Instead, according to the Chronicle of 754, Uqba carried out an attack against Berber fortresses in Africa. Initially, these attacks were unsuccessful; but eventually Uqba destroyed the rebels, secured all the crossing points to Spain, and then returned to his governorship.[121]: 105–106

Although Masayra was killed by his own followers, the revolt spread and the Berber rebels defeated three Arab armies.[121]: 106–108 After the defeat of the third army, which included elite units of Syrians commanded by Kulthum and Balj, the Berber revolt spread further. At this time, the Berber military colonies in Spain revolted.[121]: 108 At the same time, Uqba died and was replaced by Ibn Qatan. By this time, the Berbers controlled most of the north of the Iberian peninsula, except for the Ebro valley, and were menacing Toledo. Ibn Qatan invited Balj and his Syrian troops, who were at that time in Ceuta, to cross to the Iberian peninsula to fight against the Berbers.[121]: 109–110

The Berbers marched south in three columns, simultaneously attacking Toledo, Cordoba, and the ports on the Gibraltar strait. However, Ibn Qatan's sons defeated the army attacking Toledo, the governor's forces defeated the attack on Cordoba, and Balj defeated the attack on the strait. After this, Balj seized power by marching on Cordoba and executing Ibn Qatan.[121]: 108 Collins points out that Balj's troops were away from Syria just when the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads broke out, and this may have contributed to the fall of the Umayyad regime.[121]: 121

In Africa, the Berbers were hampered by divided leadership. Their attack on Kairouan was defeated, and a new governor of Africa, Hanzala ibn Safwan, proceeded to defeat the rebels in Africa and then to impose peace between Balj's troops and the existing Andalusi Arabs.[121]: 110–111

Roger Collins argues that the Great Berber revolt facilitated the establishment of the Kingdom of Asturias and altered the demographics of the Berber population in the Iberian peninsula, specifically contributing to the Berber departure from the northwest of the peninsula.[121]: 150–151 When the Arabs first invaded the peninsula, Berber groups were situated in the northwest. However, due to the Berber revolt, the Umayyad governors were forced to protect their southern flank and were unable to mount an offense against the Asturians. Some presence of Berbers in the northwest may have been maintained at first, but after the 740s there is no more mention of the northwestern Berbers in the sources.[121]: 150–151, 153–154

In al-Andalus during the Umayyad emirate

When the Umayyad Caliphate was overthrown in 750, a grandson of Caliph Hisham, Abd ar-Rahman, escaped to north Africa[121]: 115 and hid among the Berbers of north Africa for five years. A persistent tradition states that this is because his mother was Berber[121]: 117–118 and that he first took refuge with the Nafsa Berbers, his mother's people. As the governor Ibn Habib was seeking him, he then fled to the more powerful Zenata Berber confederacy, who were enemies of Ibn Habib. Since the Zenata had been part of the initial invasion force of al-Andalus, and were still present in the Iberian peninsula, this gave Abd ar-Rahman a base of support in al-Andalus,[121]: 119 although he seems to have drawn most of his support from portions of Balj's army that were still loyal to the Umayyads.[121]: 122–123 [122]: 8

Abd ar-Rahman crossed to Spain in 756 and declared himself the legitimate Umayyad ruler of al-Andalus. The governor, Yusuf, refused to submit. After losing the initial battle near Cordoba,[121]: 124–125 Yusuf fled to Mérida, where he raised a large Berber army, with which he marched on Seville, but was defeated by forces loyal to Abd ar-Rahman. Yusuf fled to Toledo, and was killed either on the way or after reaching that place.[121]: 132 Yusuf's cousin Hisham ibn Urwa continued to resist Abd ar-Rahman from Toledo until 764,[121]: 133 and the sons of Yusuf revolted again in 785. These family members of Yusuf, members of the Fihri tribe, were effective in obtaining support from Berbers in their revolts against the Umayyad regime.[121]: 134

As emir of al-Andalus, Abd ar-Rahman I faced persistent opposition from Berber groups, including the Zenata. Berbers provided much of Yusuf's support in fighting Abd ar-Rahman. In 774, Zenata Berbers were involved in a Yemeni revolt in the area of Seville.[121]: 168 Andalusi Berber Salih ibn Tarif declared himself a prophet and ruled the Bargawata Berber confederation in Morocco in the 770s.[121]: 169

In 768, a Miknasa Berber named Shaqya ibn Abd al-Walid declared himself a Fatimid imam, claiming descent from Fatimah and Ali.[121]: 168 He is mainly known from the work of the Arab historian Ibn al-Athir,[121]: 170 who wrote that Shaqya's revolt originated in the area of modern Cuenca, an area of Spain that is mountainous and difficult to traverse. Shaqya first killed the Umayyad governor of the fortress of Santaver (near Roman Ercavica), and subsequently ravaged the district surrounding Coria. Abd ar-Rahman sent out armies to fight him in 769, 770, and 771; but Shaqya avoided them by moving into the mountains. In 772, Shaqya defeated an Umayyad force by a ruse and killed the governor of the fortress of Medellin. He was besieged by Umayyads in 774, but the revolt near Seville forced the besieging troops to withdraw. In 775, a Berber garrison in Coria declared allegiance to Shaqya, but Abd ar-Rahman retook the town and chased the Berbers into the mountains. In 776, Shaqya resisted sieges of his two main fortresses at Santaver and Shebat'ran (near Toledo); but in 777 he was betrayed and killed by his own followers, who sent his head to Abd ar-Rahman.[121]: 170–171

Roger Collins notes that both modern historians and ancient Arab authors have had a tendency to portray Shaqya as a fanatic followed by credulous fanatics, and to argue that he was either self-deluded or fraudulent in his claim of Fatimid descent.[121]: 169 However, Collins considers him an example of the messianic leaders that were not uncommon among Berbers at that time and earlier. He compares Shaqya to Idris I, a descendant of Ali accepted by the Zenata Berbers, who founded the Idrisid dynasty in 788, and to Salih ibn Tarif, who ruled the Bargawata Berber in the 770s. He also compares these leaders to pre-Islamic leaders Dihya and Kusaila.[121]: 169–170

In 788, Hisham I succeeded Abd ar-Rahman as emir; but his brother Sulayman revolted and fled to the Berber garrison of Valencia, where he held out for two years. Finally, Sulayman came to terms with Hisham and went into exile in 790, together with other brothers who had rebelled with him.[121]: 203, 208 In north Africa, Sulayman and his brothers forged alliances with local Berbers, especially the Kharijite ruler of Tahert. After the death of Hisham and the accession of Al-Hakam, Hisham's brothers challenged Al-Hakam for the succession. Abd Allah[who?] crossed over to Valencia first in 796, calling on the allegiance of the same Berber garrison that sheltered Sulayman years earlier.[122]: 30 Crossing to al-Andalus in 798, Sulayman based himself in Elvira (now Granada), Ecija, and Jaen, apparently drawing support from the Berbers in these mountainous southern regions. Sulayman was defeated in battle in 800 and fled to the Berber stronghold in Mérida, but was captured before reaching it and executed in Cordoba.[121]: 208

In 797, the Berbers of Talavera played a major part in defeating a revolt against Al-Hakam in Toledo.[122]: 32 A certain Ubayd Allah ibn Hamir of Toledo rebelled against Al-Hakam, who ordered Amrus ibn Yusuf, the commander of the Berbers in Talavera, to suppress the rebellion. Amrus negotiated in secret with the Banu Mahsa faction in Toledo, promising them the governorship if they betrayed Ibn Hamir. The Banu Mahsa brought Ibn Hamir's head to Amrus in Talavera. However, there was a feud between the Banu Mahsa and the Berbers of Talavera, who killed all the Banu Mahsa. Amrus sent the heads of the Banu Mahsa along with that of Ibn Hamir to Al-Hakam in Cordoba. The Toledo rebellion was sufficiently weakened that Amrus was able to enter Toledo and convince its inhabitants to submit.[122]: 32–33

Collins argues that unassimilated Berber garrisons in al-Andalus engaged in local vendettas and feuds, such as the conflict with the Banu Mahsa.[122]: 33 This was due to the limited power of the Umayyad emir's central authority. Collins states that "the Berbers, despite being fellow Muslims, were despised by those who claimed Arab descent".[122]: 33–34 As well as having feuds with Arab factions, the Berbers sometimes had major conflicts with the local communities where they were stationed. In 794, the Berber garrison of Tarragona massacred the inhabitants of the city. Tarragona was uninhabited for seven years until the Frankish conquest of Barcelona led to its reoccupation.[122]: 34

Berber groups were involved in the rebellion of Umar ibn Hafsun from 880 to 915.[122]: 121–122 Ibn Hafsun rebelled in 880, was captured, then escaped in 883 to his base in Bobastro. There he formed an alliance with the Banu Rifa' tribe of Berbers, who had a stronghold in Alhama.[122]: 122 He then formed alliances with other local Berber clans, taking the towns of Osuna, Estepa, and Ecija in 889. He captured Jaen in 892.[122]: 122 He was only defeated in 915 by Abd ar-Rahman III.[122]: 125

Throughout the ninth century, the Berber garrisons were one of the main military supports of the Umayyad regime.[122]: 37 Although they had caused numerous problems for Abd ar-Rahman I, Collins suggests that by the reign of Al-Hakam the Berber conflicts with Arabs and native Iberians meant that Berbers could only look to the Umayyad regime for support and patronage and developed solid ties of loyalty to the emirs. However, they were also difficult to control, and by the end of the ninth century the Berber frontier garrisons disappear from the sources. Collins says this might be because they migrated back to north Africa or gradually assimilated.[122]: 37

In al-Andalus during the Umayyad caliphate

New waves of Berber settlers arrived in al-Andalus in the 10th century, brought as mercenaries by Abd ar-Rahman III, who proclaimed himself caliph in 929, to help him in his campaigns to restore Umayyad authority in areas that had overthrown it during the reigns of the previous emirs.[122]: 103, 131, 168 These new Berbers "lacked any familiarity with the pattern of relationships" that had existed in al-Andalus in the 700s and 800s;[122]: 103 thus they were not involved in the same web of traditional conflicts and loyalties as the previously already existing Berber garrisons.[122]: 168

New frontier settlements were built for the new Berber mercenaries. Written sources state that some of the mercenaries were placed in Calatrava, which was refortified.[122]: 168 Another Berber settlement called Vascos, west of Toledo, is not mentioned in the historical sources, but has been excavated archaeologically. It was a fortified town, had walls, and a separate fortress or alcazar. Two cemeteries have also been discovered. The town was established in the 900s as a frontier town for Berbers, probably of the Nafza tribe. It was abandoned soon after the Castilian occupation of Toledo in 1085. The Berber inhabitants took all their possessions with them.[122]: 169 [127]

In the 900s, the Umayyad caliphate faced a challenge from the Fatimids in North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate of the 10th century was established by the Kutama Berbers.[128][129] After taking the city of Kairouan and overthrowing the Aghlabids in 909, the Mahdi Ubayd Allah was installed by the Kutama as Imam and Caliph,[130][131] which posed a direct challenge to the Umayyad's own claim.[122]: 169 The Fatimids gained overlordship over the Idrisids, then launched a conquest of the Maghreb. To counter the threat, the Umayyads crossed the strait to take Ceuta in 931,[122]: 171 and actively formed alliances with Berber confederacies, such as the Zenata and the Awraba. Rather than fighting each other directly, the Fatimids and Umayyads competed for Berber allegiances. In turn, this provided a motivation for the further conversion of Berbers to Islam, many of the Berbers, particularly farther south, away from the Mediterranean, being still Christian and pagan.[122]: 169–170 In turn, this would contribute to the establishment of the Almoravid dynasty and Almohad Caliphate, which would have a major impact on al-Andalus and contribute to the end of the Umayyad caliphate.[122]: 170

With the help of his new mercenary forces, Abd ar-Rahman launched a series of attacks on parts of the Iberian peninsula that had fallen away from Umayyad allegiance. In the 920s he campaigned against the areas that rebelled under Umar ibn Hafsun and refused to submit until the 920s. He conquered Mérida in 928–929, Ceuta in 931, and Toledo in 932.[122]: 171–172 In 934 he began a campaign in the north against Ramiro II of Leon and Muhammad ibn Hashim al-Tujibi, the governor of Zaragoza. According to Ibn Hayyan, after inconclusively confronting al-Tujibi on the Ebro, Abd ar-Rahman briefly forced the Kingdom of Pamplona into submission, ravaged Castile and Alava, and met Ramiro II in an inconclusive battle.[122]: 171–172 From 935 to 937, he confronted the Tujibids, defeating them in 937. In 939, Ramiro II defeated the combined Umayyad and Tujibid armies in the Battle of Simancas.[122]: 146–147

Umayyad influence in western North Africa spread through diplomacy rather than conquest.[122]: 172 The Umayyads sought out alliances with various Berber confederacies. These would declare loyalty to the Umayyad caliphate in opposition to the Fatimids. The Umayyads would send gifts, including embroidered silk ceremonial cloaks. During this time, mints in cities on the Moroccan coast—Fes, Sijilmasa, Sfax, and al-Nakur—occasionally issued coins with the names of Umayyad caliphs, showing the extent of Umayyad diplomatic influence.[122]: 172 The text of a letter of friendship from a Berber leader to the Umayyad caliph has been preserved in the work of 'Isa al-Razi.[132]

During Abd ar-Rahman's reign, tensions increased between the three distinct components of the Muslim community in al-Andalus: Berbers, Saqaliba (European slaves), and those of Arab or mixed Arab and Gothic descent.[122]: 175 Following Abd ar-Rahman's proclamation of the new Umayyad caliphate in Cordoba, the Umayyads placed a great emphasis on the Umayyad membership of the Quraysh tribe.[122]: 180 This led to a fashion, in Cordoba, for claiming pure Arab ancestry as opposed to descent from freed slaves.[122]: 181 Claims of descent from Visigothic noble families also became common.[122]: 181–182 However, an "immediately detrimental consequence of this acute consciousness of ancestry was the revival of ethnic disparagement, directed in particular against the Berbers and the Saqaliba".[122]: 182

When the Fatimids moved their capital to Egypt in 969, they left north Africa in charge of viceroys from the Zirid clan of Sanhaja Berbers, who were Fatimid loyalists and enemies of the Zenata.[122]: 170 The Zirids in turn divided their territories, assigning some to the Hammadid branch of the family to govern. The Hammadids became independent in 1014, with their capital at Qal'at Beni-Hammad. With the withdrawal of the Fatimids to Egypt, however, the rivalry with the Umayyads decreased.[122]: 170

Al-Hakam II sent Muhammad Ibn Abī ‘Āmir to north Africa in 973–974 to act as qadi al qudat (chief justice) to the Berber groups that had accepted Umayyad authority. Ibn Abī ‘Āmir was treasurer of the household of the caliph's wife and children, director of the mint at Madinat al-Zahra, commander of the Cordoba police, and qadi of the frontier. During his time as qadi in north Africa, Ibn Abi Amir developed close ties with the North African Berbers.[122]: 186

Considerable resentment arose in Cordoba against the increasing numbers of Berbers brought from north Africa by al-Mansur and his children Abd al-Malik and Sanchuelo.[122]: 198 It was said that Sanchuelo ordered anyone attending his court to wear Berber turbans, which Roger Collins suggests may not have been true, but shows that hostile anti-Berber propaganda was being used to discredit the sons of al-Mansur. In 1009, Sanchuelo had himself proclaimed Hisham II's successor, and then went on military campaign. However, while he was away a revolt took place. Sanchuelo's palace was sacked and his support fell away. As he marched back to Cordoba his own Berber mercenaries abandoned him.[122]: 197–198 Knowing the strength of ill feeling against them in Cordoba, they thought Sanchuelo would be unable to protect them, and so they went elsewhere in order to survive and secure their own interests.[122]: 198 Sanchuelo was left with only a few followers, and was captured and killed in 1009. Hisham II abdicated and was succeeded by Muhammad II al-Mahdi.

Having abandoned Sanchuelo, the Berbers who had formed his army turned to support another ambitious Umayyad, Sulayman. They obtained logistical support from Count Sancho Garcia of Castile. Marching on Cordoba, they defeated Saqaliba general Wadih and forced Muhammad II al-Mahdi to flee to Toledo. They then installed Sulayman as caliph, and based themselves in the Madinat al-Zahra to avoid friction with the local population.[122]: 198–199 Wadih and al-Mahdi formed an alliance with the Counts of Barcelona and Urgell and marched back on Cordoba. They defeated Sulayman and the Berber forces in a battle near Cordoba in 1010. To avoid being destroyed, the Berbers fled towards Algeciras.[122]: 199

Al-Mahdi swore to exterminate the Berbers and pursued them. However, he was defeated in battle near Marbella. With Wadih, he fled back to Cordoba while his Catalan allies went home. The Berbers turned around and besieged Cordoba. Deciding that he was about to lose, Wadih overthrew al-Mahdi and sent his head to the Berbers, replacing him with Hisham II.[122]: 199 However, the Berbers did not end the siege. They methodically destroyed Cordoba's suburbs, pinning the inhabitants inside the old Roman walls and destroying the Madinat al-Zahra. Wadih's allies killed him, and the Cordoba garrison surrendered with the expectation of amnesty. However, "a massacre ensued in which the Berbers took revenge for many personal and collective injuries and permanently settled several feuds in the process".[122]: 200 The Berbers made Sulayman caliph once again. Ibn Idhari said that the installation of Sulayman in 1013 was the moment when "the rule of the Berbers began in Cordoba and that of the Umayyads ended, after it had existed for two hundred and sixty eight years and forty-three days".[122]: 200 [133]

In al-Andalus in the Taifa period

During the Taifa era, the petty kings came from a variety of ethnic groups; some—for instance the Zirid kings of Granada—were of Berber origin. The Taifa period ended when a Berber dynasty—the Moroccan Almoravids—took over al-Andalus; they were succeeded by the Almohad dynasty of Morocco, during which time al-Andalus flourished.

After the fall of Cordoba in 1013, the Saqaliba fled from the city to secure their own fiefdoms. One group of Saqaliba seized Orihuela from its Berber garrison and took control of the entire region.[122]: 201

Among the Berbers who were brought to al-Andalus by al-Mansur were the Zirid family of Sanhaja Berbers. After the fall of Cordoba, the Zirids took over Granada in 1013, forming the Zirid kingdom of Granada. The Saqaliba Khayran, with his own Umayyad figurehead Abd ar-Rahman IV al-Murtada, attempted to seize Granada from the Zirids in 1018, but failed. Khayran then executed Abd ar-Rahman IV. Khayran's son, Zuhayr, also made war on the Zirid kingdom of Granada, but was killed in 1038.[122]: 202

In Cordoba, conflicts continued between the Berber rulers and those of the citizenry who saw themselves as Arab.[122]: 202 After being installed as caliph with Berber support, Sulayman was pressured into distributing southern provinces to his Berber allies. The Sanhaja departed from Cordoba at this time. The Zenata Berber Hammudids received the important districts of Ceuta and Algeciras. The Hammudids claimed a family relation to the Idrisids, and thus traced their ancestry to the caliph Ali. In 1016 they rebelled in Ceuta, claiming to be supporting the restoration of Hisham II. They took control of Málaga, then marched on Cordoba, taking it and executing Sulayman and his family. Ali ibn Hammud al-Nasir declared himself caliph, a position he held for two years.[122]: 203

For some years, Hammudids and Umayyads fought one another and the caliphate passed between them several times. Hammudids also fought among themselves. The last Hammudid caliph reigned until 1027. The Hammudids were then expelled from Cordoba, where there was still a great deal of anti-Berber sentiment. The Hammudids remained in Málaga until expelled by the Zirids in 1056.[122]: 203 The Zirids of Granada controlled Málaga until 1073, after which separate Zirid kings retained control over the taifas of Granada and Malaga until the Almoravid conquest.[134]

During the taifa period, the Aftasid dynasty, based in Badajoz, controlled a large territory centered on the Guadiana River valley.[134] The area of Aftasid control was very large, stretching from the Sierra Morena and the taifas of Mértola and Silves in the south, to the Campo de Calatrava in the west, the Montes de Toledo in the northwest, and nearly as far as Oporto in the northeast.[134]

According to Bernard Reilly,[134]: 13 during the taifa period genealogy continued to be an obsession of the upper classes in al-Andalus. Most wanted to trace their lineage back to the Syrian and Yemeni Arabs who accompanied the invasion. In contrast, tracing descent from the Berbers who came with the same invasion "was to be stigmatized as of inferior birth".[134]: 13 Reilly notes, however, that in practice the two groups had by the 11th century become almost indistinguishable: "both groups gradually ceased to be distinguishable parts of the Muslim population, except when one of them actually ruled a taifa, in which case his low origins were well publicized by his rivals".[citation needed]

Nevertheless, distinctions between Arab, Berber, and slave were not the stuff of serious politics, either within or between the taifas. It was the individual family that was the unit of political activity."[134]: 13 The Berber that arrived towards the end of the caliphate as mercenary forces, says Reilly, amounted to only about 20 thousand people in a total al-Andalusi population of six million. Their high visibility was due to their foundation of taifa dynasties rather than large numbers.[134]: 13

In the power hierarchy, Berbers were situated between the Arabic aristocracy and the Muladi populace. Ethnic rivalry was one of the most important factors driving Andalusi politics. Berbers made up as much as 20% of the population of the occupied territory.[135]

In al-Andalus under the Almoravids

During the taifa period, the Almoravid empire developed in northwest Africa, whose core was formed by the Lamtuna branch of the Sanhaja Berber.[134]: 99 In the mid-11th century, they allied with the Guddala and Massufa Berber. At that time, the Almoravid leader Yahya ibn Ibrahim went on a hajj. On his way back he met Malikite preachers in Kairouan, and invited them to his land. Malikite disciple Abd Allah ibn Yasin accepted the invitation. Traveling to Morocco, he established a military monastery or ribat where he trained a highly motivated and disciplined fighting force. In 1054 and 1055, employing these specially trained forces, Almoravid leader Yahya ibn Umar defeated the Kingdom of Ghana and the Zenata Berber. After Yahya ibn Umar died, his brother Abu Bakr ibn Umar pursued an Almoravid expansion. Forced to resolve a Sanhaja civil war, he left control of the Moroccan conquests to his brother, Yusuf ibn Tashfin. Yusuf continued to conquer territory; and following Abu Bakr's death in 1087, he became the Almoravid leader.[134]: 100–101

After their loss of Cordoba, the Hammudids had occupied Algeciras and Ceuta. In the mid-11th century, the Hammudids lost control of their Iberian possessions, but retained a small taifa kingdom based in Ceuta. In 1083, Yusuf ibn Tashufin conquered Ceuta. In the same year, al-Mutamid, king of the Taifa of Seville, traveled to Morocco to appeal to Yusuf for help against King Alfonso VI of Castile. Earlier, in 1079, the king of Badajoz, al-Mutawakkil, had appealed to Yusuf for help against Alfonso. After the fall of Toledo to Alfonso VI in 1085, al-Mutamid appealed again to Yusuf. This time, financed by the taifa kings of Iberia, Yusuf crossed to al-Andalus and took direct personal control of Algeciras in 1086.[134]: 102–103

Modern history

The Kabylians were independent of outside control during the period of Ottoman Empire rule in North Africa. They lived primarily in three states or confederations: the Kingdom of Ait Abbas, Kingdom of Kuku, and the principality of Aït Jubar.[136] The Kingdom of Ait Abbas was a Berber state of North Africa, controlling Lesser Kabylie and its surroundings from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century. It is referred to in the Spanish historiography as reino de Labes;[137] sometimes more commonly referred to by its ruling family, the Mokrani, in Berber At Muqran (Arabic: أولاد مقران Ouled Moqrane). Its capital was the Kalâa of Ait Abbas, an impregnable citadel in the Biban mountain range.

The most serious native revolt against colonial power in French Algeria since the time of Abd al-Qadir broke out in 1871 in the Kabylie and spread through much of Algeria. By April 1871, 250 tribes had risen, or nearly a third of Algeria's population.[138] In the aftermath of this revolt and until 1892, the Kabyle myth, which supposed a variety of stereotypes based on a binary between Arabs and Kabyle people, reached its climax.[139][140]

In 1902, the French penetrated the Hoggar Mountains and defeated Ahaggar Tuareg in the battle of Tit.

In 1912, Morocco was divided into French and Spanish zones.[141] The Rif Berbers rebelled, led by Abd el-Krim, a former officer of the Spanish administration. In July 1921, the Spanish army in northeastern Morocco, under Manuel Silvestre, were routed by the forces of Abd el-Krim, in what became known in Spain as the Disaster of Annual. The Spaniards may have lost up to 22,000 soldiers at Annual and in subsequent fighting.[142]

During the Algerian War (1954–1962), the FLN and ALN's reorganisation of the country created, for the first time, a unified Kabyle administrative territory, wilaya III, being as it was at the centre of the anti-colonial struggle.[143] From the moment of Algerian independence, tensions developed between Kabyle leaders and the central government.[144]

Soon after gaining independence in the middle of the twentieth century, the countries of North Africa established Arabic as their official language, replacing French, Spanish, and Italian; although the shift from European colonial languages to Arabic for official purposes continues even to this day. As a result, most Berbers had to study and know Arabic, and had no opportunities until the twenty-first century to use their mother tongue at school or university. This may have accelerated the existing process of Arabization of Berbers, especially in already bilingual areas, such as among the Chaouis of Algeria. Tamazight is now taught in Aurès since the march led by Salim Yezza in 2004.

While Berberism had its roots before the independence of these countries, it was limited to the Berber elite. It only began to succeed among the greater populace when North African states replaced their European colonial languages with Arabic and identified exclusively as Arabian nations, downplaying or ignoring the existence and the social specificity of Berbers. However, Berberism's distribution remains uneven. In response to its demands, Morocco and Algeria have both modified their policies, with Algeria redefining itself constitutionally as an "Arab, Berber, Muslim nation".

There is an identity-related debate about the persecution of Berbers by the Arab-dominated regimes of North Africa through both Pan-Arabism and Islamism,[145] their issue of identity is due to the pan-Arabist ideology of former Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Some activists have claimed that "[i]t is time—long past overdue—to confront the racist arabization of the Amazigh lands."[146]

The Black Spring was a series of violent disturbances and political demonstrations by Kabyle activists in the Kabylie region of Algeria in 2001. In the 2011 Libyan civil war, Berbers in the Nafusa Mountains were quick to revolt against the Gaddafi regime. The mountains became a stronghold of the rebel movement, and were a focal point of the conflict, with much fighting occurring between rebels and loyalists for control of the region.[4] The Tuareg Rebellion of 2012 was waged against the Malian government by rebels with the goal of attaining independence for the northern region of Mali, known as Azawad.[147] Since late 2016, massive riots have spread across Moroccan Berber communities in the Rif region. Another escalation took place in May 2017.[148]

In Morocco, after the constitutional reforms of 2011, Berber has become an official language, and is now taught as a compulsory language in all schools regardless of the area or the ethnicity. In 2016, Algeria followed suit and changed the status of Berber from "national" to "official" language.

Although Berberists who openly show their political orientations rarely reach high positions, Berbers have reached high positions in the social and political hierarchies across the Maghreb. Examples are the former president of Algeria, Liamine Zeroual; the former prime minister of Morocco, Driss Jettou; and Khalida Toumi, a feminist and Berberist militant, who has been nominated as head of the Ministry of Communication in Algeria.

Remove ads

Arabization

Summarize

Perspective

The Arabization of the indigenous Berber populations was a result of the centuries-long Arab migrations to the Maghreb which began since the 7th century, in addition to changing the population's demographics. The early wave of migration prior to the 11th century contributed to the Berber adoption of Arab culture. Furthermore, the Arabic language spread during this period and drove Latin into extinction in the cities. The Arabization took place around Arab centres through the influence of Arabs in the cities and rural areas surrounding them.[149]

The migration of Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym in the 11th century had a much greater influence on the process of Arabization of the population. It played a major role in spreading Bedouin Arabic to rural areas such as the countryside and steppes, and as far as the southern areas near the Sahara.[149] It also heavily transformed the culture in the Maghreb into Arab culture, and spread nomadism in areas where agriculture was previously dominant.[150] These Bedouin tribes accelerated and deepened the Arabization process, since the Berber population was gradually assimilated by the newcomers and had to share with them pastures and seasonal migration paths. By around the 15th century, the region of modern-day Tunisia had already been almost completely Arabized.[51] As Arab nomads spread, the territories of the local Berber tribes were moved and shrank. The Zenata were pushed to the west and the Kabyles were pushed to the north. The Berbers took refuge in the mountains whereas the plains were Arabized.[151]

Currently, most Arabized Berbers identify as Berber, although the prominence of Arab influences has fully assimilated them into the Arab cultural sphere.[152]

Contemporary demographics

Summarize

Perspective

Ethnic groups

Ethnically, Berbers comprise a minority population in the Maghreb. Berbers comprise 15%[153] to 25%[154] the population of Algeria, 10%[155] of Libya, 31%[156] to 35%[157] of Morocco, and 1%[158] of Tunisia. Berber language speakers in the Maghreb comprise 30%[4] to 40%[159][better source needed][16][better source needed] of the Moroccan population, and 15%[160] to 35%[16][better source needed] of the Algerian population, with smaller communities in Libya and very small groups in Tunisia, Egypt and Mauritania.[161] Berber languages in total are spoken by around 14 million[162] to 16 million[163] people in Africa.

Prominent Berber ethnic groups include the Kabyles—from Kabylia, a historical autonomous region of northern Algeria—who number about six million and have kept, to a large degree, their original language and society; and the Shilha or Chleuh—in High and Anti-Atlas and Sous Valley of Morocco—who number about eight million.[citation needed] Other groups include the Riffians of northern Morocco, the Chaoui people of eastern Algeria, the Chenouas in western Algeria and the Nafusis of the Nafusa Mountains.

Outside the Maghreb, the Tuareg in Mali (early settlement near the old imperial capital of Timbuktu),[164] Niger, and Burkina Faso number some 850,000,[20] 1,620,000,[165] and 50,000, respectively. Tuaregs are a Berber ethnic group with a traditionally nomadic pastoralist lifestyle and are the principal inhabitants of the vast Sahara Desert.[166][167]

Genetics

Genetically, the Berbers form the principal indigenous ancestry in the region.[185][186] Haplogroup E1b1b is the most frequent among Maghrebi groups, especially the downstream lineage of E1b1b1b1a, which is typical of the indigenous Berbers of North-West Africa. On the other hand, Haplogroup J1 is the second most frequent among Maghrebi groups and is more indicative of Middle East origins, and has its highest distribution among populations in the southern Arabian Peninsula. E1b1b1b accounts for 45% of North Africans, while Haplogroup J1-M267 accounts for 30% of North Africans, and has spread from Arabia.[187]

The Semitic-speaking presence in the Maghreb is mainly due to the migratory movements of Phoenicians in the 3rd century BC and large scale migrations of Arab Bedouin tribes in the 11th century AD such as Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, as well as other waves that occurred during the Arab migrations to the Maghreb (c. 7th century – 17th century). The results of a study from 2017 suggest that these Arab migrations to the Maghreb were mainly a demographic process that heavily implied gene flow and remodeled the genetic structure of the Maghreb.[188]

DNA studies of Iberomaurusian peoples at Taforalt, Morocco dating to around 15,000 years ago have found them to have a distinctive Maghrebi ancestry formed from a mixture of Near Eastern and African ancestry, which is still found as a part of the genome of modern Northwest Africans.[189] A 2025 study sequenced individuals from Takarkori (7,000 YBP) and discovered that most of their ancestry was from an unknown Ancestral North African lineage, related to the African admixture component found in Iberomaurusians.[190] According to the study, the Takarkori people were distinct from both contemporary sub-Saharan Africans and non-Africans/Eurasians. They had "only a minor component of non-African ancestry" but did "not carry sub-Saharan African ancestry, suggesting that, contrary to previous interpretations, the Green Sahara was not a corridor connecting Northern and sub-Saharan Africa."[191]

Later during the Neolithic, from around 7,500 years ago onwards, there was a migration into Northwest Africa of European Neolithic Farmers from the Iberian Peninsula (who had originated in Anatolia several thousand years prior), as well as pastoralists from the Levant, both of whom also significantly contributed to the ancestry of modern Northwest Africans.[192] The proto-Berber tribes evolved from these prehistoric communities during the late Bronze- and early Iron ages.[193]

Remove ads

Diaspora

According to a 2004 estimate, there were about 2.2 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians in Belgium, the Netherlands, and France; and Algerians of Kabyles and Chaouis heritage in France.[194]

Remove ads

Politics

Summarize

Perspective

Berberism

Since the 1970s,[195]: 209 a political movement, initially led by the Kabyles of Algeria, has developed among various parts of the Berber populations of North Africa to promote a collective Amazigh ethnic identity.[55] It is variously referred to as Amazighism,[196] Berberism,[195] the Berber identity movement, or the Berber Culture Movement.[55] The movement does not have a specific organization and cuts across both modern national boundaries and traditional tribal divisions. It is generally consistent in its demands, which include greater linguistic rights for Berber languages and greater official and social recognition of Amazigh culture.[55] These Berberists also aimed to counter the image that Berbers were a mere collection of disparate tribes speaking mutually incomprehensible languages. They did this by introducing "Imazighen" as a collective term of self-referral and claimed that the various Berber languages once constituted a single language.[53]

The political outcomes have been different in each country of the Maghreb and are shaped by other factors such as geography and socioeconomic circumstances. In Algeria, the politics of the movement were focused in Kabylie, were more overtly political, and have sometimes been confrontational. In Morocco, where Amazigh populations are spread across a wider area, the movement has been less overtly political and confrontational.[55][195]: 213 In the 1990s, both states made concessions to this movement or attempted to ally itself with it, partly in response to the challenge of other political forces such as Islamism.[195]: 214

Political tensions

Over the past few decades, political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups (especially the Kabyles and Rifians) and North African governments, partly over linguistic and social issues. For example, in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, giving children Berber names was banned.[197][198][199] In Morocco, the Arabic language and Arab culture occupied a superior position in official and social domains. The Arabist ideology was popular among Moroccan society, as well as within bureaucratic cadres and the political parties.[200] The regime of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya also banned the teaching of Berber languages, and, in a 2008 leaked diplomatic cable, the Libyan leader warned Berber minorities: "You can call yourselves whatever you want inside your homes – Berbers, Children of Satan, whatever – but you are only Libyans when you leave your homes."[201] He denied the existence of Berbers as a separate ethnicity, and called them a "product of colonialism" created by the West to divide Libya.[202][203] As a result of the persecution suffered under Gaddafi's rule, many Berbers joined the Libyan opposition in the 2011 Libyan civil war.[204]

In contrast, many Berber students in Morocco supported Nasserism and Arabism, rather than Berberism. Many educated Berbers were attracted to the leftist National Union of Popular Forces rather than the Berber-based Popular Movement.[200]

Remove ads

Languages

Summarize

Perspective

The Berber languages form a branch of the Afroasiatic language family, a large family that also includes Semitic languages like Arabic and the Ancient Egyptian language.[205][206] Most Berbers speak Arabic and French.[207]

Tamazight is a generic name for all of the Berber languages, which consist of many closely related varieties and dialects. Among these Berber languages are Riffian, Zuwara, Kabyle, Shilha, Siwi, Zenaga, Sanhaja, Tazayit (Central Atlas Tamazight), Tumẓabt (Mozabite), Nafusi, and Tamasheq, as well as the ancient Guanche language.

Most Berber languages have a high percentage of borrowing and influence from the Arabic language, as well as from other languages.[208] For example, Arabic loanwords represent 35%[209] to 46%[210] of the total vocabulary of the Kabyle language and represent 51.7% of the total vocabulary of Tarifit.[211] The least influenced are the Tuareg languages.[208] Almost all Berber languages took from Arabic the pharyngeal fricatives /ʕ/ and /ħ/, the (nongeminated) uvular stop /q/, and the voiceless pharyngealized consonant /ṣ/.[212] In turn, Berber languages have influenced local dialects of Arabic. Although Maghrebi Arabic has a predominantly Semitic and Arabic vocabulary,[213] it contains a few Berber loanwords which represent 2–3% of the vocabulary of Libyan Arabic, 8–9% of Algerian Arabic and Tunisian Arabic, and 10–15% of Moroccan Arabic.[214]

Berber languages in total are spoken by around 14 million[162] to 16 million[163] people in Africa (see population estimation). These Berber speakers are mainly concentrated in Morocco and Algeria, followed by Mali, Niger, and Libya. Smaller Berber-speaking communities are also found as far east as Egypt, with a southwestern limit today at Burkina Faso.

Remove ads

Religion

Summarize

Perspective

The Berber identity encompasses language, religion, and ethnicity, and is rooted in the entire history and geography of North Africa. Berbers are not an entirely homogeneous ethnicity, and they include a range of societies, ancestries, and lifestyles. The unifying forces for the Berber people may be their shared language or a collective identification with Berber heritage and history.