Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

First premiership of Mahathir Mohamad

Government of Malaysia from 1981 to 2003 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

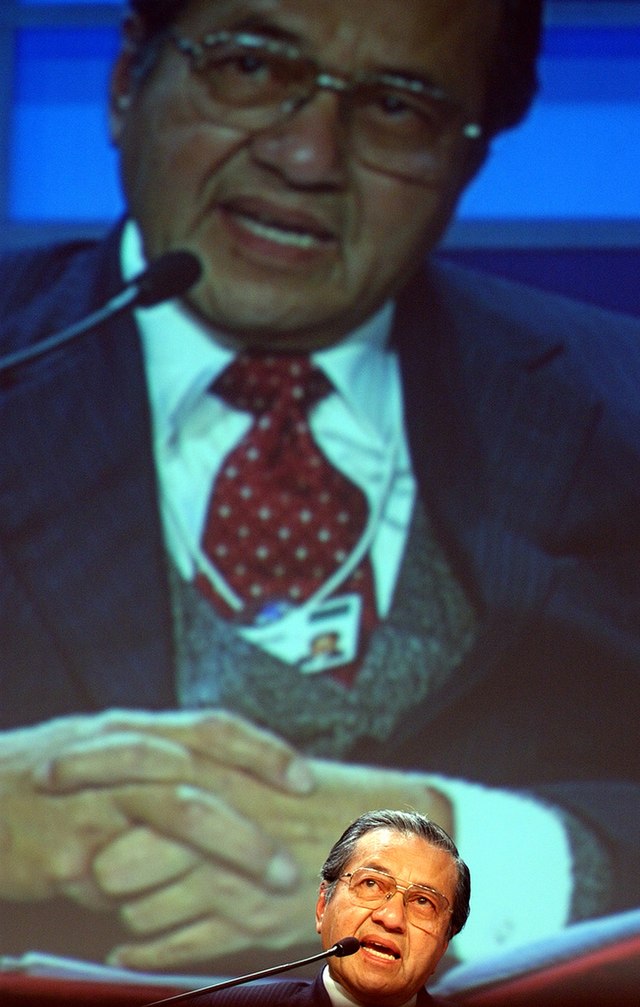

Mahathir Mohamad was sworn in as Malaysia’s fourth prime minister on 16 July 1981. This marked the beginning of his first premiership, which lasted until 2003, the longest in the country’s history. He adopted the slogan "Clean, Efficient and Trustworthy" (Bersih, Cekap dan Amanah) and introduced wide-ranging political, economic, and administrative reforms to modernize Malaysia and strengthen its presence on the global stage.

Domestically, Mahathir continued and modified the Malaysian New Economic Policy (NEP), promoting Bumiputera economic participation through privatization, industrialization, and major infrastructure projects such as the North–South Expressway and the development of Langkawi as a duty-free island. He also adopted a firm anti-drug stance, introducing stricter laws and public campaigns to combat drug abuse across the country. In 1991, following the conclusion of the NEP, he introduced the National Development Policy (NDP), which retained affirmative action elements but placed greater emphasis on economic growth, private sector expansion, and poverty reduction. That same year, he announced Vision 2020, a national agenda to transform Malaysia into a developed country by the year 2020. During the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, Mahathir took unorthodox measures including capital controls and a fixed exchange rate, which helped stabilize the economy and avoid IMF intervention.

Politically, Mahathir sought to modernize Malaysia’s governance by centralizing executive power and improving administrative efficiency. In 1987, Mahathir narrowly defeated Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah in a heated UMNO party election, a contest that deepened internal divisions and later led to the formation of a new UMNO in 1988. During his tenure, Mahathir’s government curbed the constitutional powers of the monarchy, including the removal of royal immunity from prosecution, thereby affirming the authority of the elected government within a parliamentary democracy. However, his leadership also saw challenges, including a major political crisis in 1998 when he dismissed Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, an event that drew widespread public attention and international scrutiny.

In foreign policy, Mahathir pursued the “Look East Policy” to deepen ties with Japan and South Korea, and temporarily boycotted British goods in response to diplomatic tensions, before later reconciling with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. He played an active role in international diplomacy, supporting anti-apartheid efforts in South Africa and advocating for Muslims in Bosnia. His tenure fundamentally reshaped Malaysia’s political and economic landscape, establishing his legacy as one of the most influential leaders in the developing world. Mahathir voluntarily retired in October 2003 and was succeeded by his deputy, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. He was granted the soubriquet "Father of Modernisation" ("Bapa Pemodenan") of Malaysia.

Remove ads

First 100 days

Summarize

Perspective

On 16 July 1981, Mahathir was officially appointed as Malaysia's fourth Prime Minister by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah, and was sworn in during a ceremony attended by acting Chief Justice Sultan Azlan Shah and Chief Secretary to the Government Hashim Aman.[1] The swearing-in ceremony, which took 10 minutes, was witnessed by all Cabinet ministers except for Foreign Minister Tengku Ahmad Rithauddeen Ismail, who was in New York.[2] He said effective implementation of the economic programme and strengthening of relations with the neighbouring ASEAN countries would be the priority items in his domestic and foreign policies.[3] Two days after his appointment, Mahathir announced a cabinet reshuffle,[4] including the appointment of Musa Hitam as deputy prime minister.[5]

At his first Cabinet meeting on 23 July, Mahathir announced that the government had chosen the contractor and decided on a concrete girder type design for the long-planned Penang Bridge project.[6] Shortly after taking office, he freed 21 political prisoners, including Kassim Ahmad, chairman of the opposition Malaysian People's Socialist Party, and two members of parliament from the Democratic Action Party, while also lifting the ban on his book The Malay Dilemma.[7]

Mahathir implemented a new initiative to promote punctuality in the government by introducing a clock-in system for all ministers and senior officials. The system required even top leaders to "punch" in, setting an example for the rest of the civil service.[8] His policy quickly showed results, reducing tardiness among civil servants and easing traffic jams in Kuala Lumpur as workers began their journeys earlier to avoid penalties for being late to government offices.[9] Mahathir later said he introduced the system because he noticed then that some civil servants left the office at 3pm.[10]

Throughout August, he welcomed Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang[11] and made his first official visits to Indonesia[12] and Thailand.[13] Zhao assured Mahathir that China had made efforts to distance itself from the Communist Party of Malaya, and Mahathir responded that Malaysia would only be fully satisfied if China severed all ties with the CPM.[14] On 29 August, The Straits Times commented that in just six weeks, Mahathir had shown he meant business through bold actions and rapid reforms, with his hyperactive movements generating almost daily headlines in the local press.[15] Meanwhile, Mahathir fell ill with an upset stomach during an open-air rally in Alor Star, and had to cut short his speech;[16] this also prompted him to leave for a two-week vacation in Spain and Portugal with his family starting from September 1, during which Musa Hitam acted as prime minister.[17]

In September, during a meeting with Iranian Parliament Speaker Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mahathir offered Malaysia's assistance for Iran's development programme, pledged to strengthen economic and trade cooperation, and reaffirmed Malaysia's commitment to helping resolve the Iran-Iraq conflict.[18] Meanwhile, Mahathir announced that he would not attend the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Melbourne, citing heavy workload in Malaysia and criticising the Commonwealth for producing "too much talk and very little results.[19] He approved a secretive stock market operation known as the "Dawn Raid" on the London Stock Exchange, enabling Malaysian agency Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) to regain majority control of Guthrie, a major British plantation company.[20]

On 23 October, as Mahathir was nearing his first 100 days as prime minister, Finance Minister Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah introduced a budget focused on tax cuts, inflation control, and encouraging savings and tourism.[21] Mahathir believed that the removal of various taxes under the 1982 Budget would stimulate Malaysia's commercial sector and strengthen its tourism industry.[22]

Remove ads

Domestic affairs

Summarize

Perspective

Mahathir launched the 'Bersih, Cekap & Amanah' campaign to improve government efficiency and combat corruption.[23] He explained that the concept emphasized administrative integrity, public service responsiveness, and disciplined, hardworking personnel guided by strong ethical values and a commitment to the public good.[24]

In 1989, Mahathir oversaw peace talks with the Communist Party of Malaya, resulting in the Hat Yai Agreement that ended the decades-long conflict.[25][26]

Under his leadership, the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Malaysia Plans were successively introduced.[27]

Change of Malaysian Standard Time

In December 1981, Mahathir proposed a change to Malaysia's official time to standardise the time zone across the country. Before this adjustment, Peninsular Malaysia operated at GMT+7:30 while Sabah and Sarawak used GMT+8:00. The half-hour difference had existed since before the formation of Malaysia in 1963. Mahathir introduced a motion in the Dewan Rakyat to move Peninsular Malaysia’s time forward by 30 minutes to match that of East Malaysia, with the change coming into effect on 1 January 1982. The proposal was approved by both houses of Parliament without amendment.[28] Following Mahathir's visit to Singapore and discussions with Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, the Singapore government also decided to adopt the same time zone adjustment in order to maintain synchronisation with Malaysia.[29] The policy has remained in effect without change since its introduction in 1982.[30]

Economic policy

During his tenure as prime minister, Mahathir implemented major structural reforms aimed at reducing the public sector's role in the economy. When he assumed office, Malaysia faced high budget deficits—peaking at 15% of GDP in 1982—and a federal debt level that reached over 100% of GDP by 1987. In response, Mahathir cut development spending and promoted private sector-led growth. These fiscal adjustments coincided with a recession in 1985, but they laid the groundwork for sustained economic expansion from 1988 to 1996, when GDP growth averaged 9.5% annually.[31]

Mahathir launched the "Malaysia Incorporated" concept in 1983, which envisioned the government and private sector working as partners in national development.[32] In line with this vision, he trimmed the civil service through the privatisation of government agencies.[33] The policy aimed to reduce the government's role in the economy and to promote private sector growth.[34] Industries such as telecommunications, utilities, and airlines were privatised, resulting in the establishment of major companies like Telekom Malaysia, Tenaga Nasional, and Malaysia Airlines (MAS).[34] By the time Mahathir stepped down in 2003, the number of civil servants had fallen to below one million.[33] However, during Najib Razak's tenure as prime minister, the civil service grew again relative to the population, which drew criticism.[33]

Mahathir successfully diversified Malaysia's economy from reliance on raw material exports to include manufacturing, services, and tourism.[35] The number of listed companies rose from 253 in 1981 to 906 by the end of 2003, while market capitalisation expanded from RM55 billion to RM640 billion.[36] Funds raised through the equity market increased from RM930 million in 1981 to RM7.6 billion in 2003.[36] By the end of his tenure, Malaysia had become one of the world's leading emerging economies, ranking as the 17th largest trading nation globally and 4th in trade competitiveness, behind only the United States, Canada, and Australia in 2003.[36]

During the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, Malaysia faced severe economic turmoil as the ringgit lost 35% of its value, foreign reserves dwindled, and the stock market halved. Mahathir refused to accept an IMF bailout, rejecting the austerity measures imposed by global lenders, and instead implemented unorthodox policies including capital controls, a fixed exchange rate, and lower interest rates. Though initially criticised, his measures stabilised the economy, restored investor confidence, and enabled Malaysia to recover rapidly—contracting 7.4% in 1998 but rebounding with 6.1% growth in 1999—while avoiding the social and political upheaval seen in countries like Indonesia and Thailand. Mahathir’s bold defiance of conventional economic wisdom was later vindicated by economists such as Paul Krugman and even acknowledged by the IMF and World Bank.[37]

Industrialisation and infrastructure development

During his tenure as prime minister, Mahathir initiated numerous large-scale infrastructure projects.[38]

As early as July 1979, when Mahathir was serving as minister of trade and industry, he proposed a feasibility study on the development of a Malaysian-manufactured car, based on the view that heavy industries were important for national economic development.[39] In October 1981, after becoming prime minister, Mahathir invited Yohei Mimura, the then president of Mitsubishi Corporation, to consider participating in the project.[39] In January 1983, Mahathir visited Mitsubishi's Okazaki plant, where he was shown two proposed models, codenamed LM41 and LM44, as potential bases for Malaysia's national car initiative.[39]

The national car project was approved in 1982, and Perusahaan Otomobil Nasional (Proton) was established on 7 May 1983. The company was placed under the ownership of Khazanah Nasional, Malaysia's sovereign wealth fund.[40] By 1985, Mahathir introduced the Proton Saga, the country's first national car.[41] The Proton Saga quickly gained popularity in Malaysia and secured a 64% market share within its segment by 1986. Following this domestic success, Proton expanded into the European market, beginning with the United Kingdom. In 1988, Proton showcased the Saga at the British International Motor Show, where it received three awards for quality, coachwork, and ergonomics. The model was also recognised as the fastest-selling new car make ever to enter the UK market at the time.[42]

Mahathir significantly developed Langkawi by declaring it a duty-free zone in 1987, boosting trade and tourism. He upgraded infrastructure, including a modern airport, and created the Langkawi Development Authority (LADA) to ensure dedicated funding. His efforts attracted investment and major events, including the signing of the Langkawi Declaration on Environment at the 1989 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM). Mahathir also initiated key events such as Le Tour de Langkawi, the Royal Langkawi International Regatta, and the Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition, solidifying Langkawi's status as a key tourism hub.[43]

The North–South Expressway (NSE) was revived during the administration of Mahathir in the 1980s.[44] Spanning approximately 847.7 km from Bukit Kayu Hitam in Kedah near the Malaysia–Thailand border to Johor Bahru in the south, it became the longest expressway in Malaysia.[45] The expressway was completed in stages and officially launched by Mahathir on 8 September 1994.[44]

MEASAT (Malaysia East Asia Satellite) was Malaysia's first communications satellite initiative, launched under the leadership of Mahathir in 1993. At the time, the telecommunications sector in Malaysia was heavily dominated by Telekom Malaysia Berhad (TM), a government-owned entity. To break this monopoly and encourage private sector participation, Mahathir facilitated the establishment of Binariang Sdn Bhd, a privately owned company that was awarded the contract to operate the MEASAT system. Binariang later became known as Maxis. In 1994, Binariang signed a contract with Hughes Space and Communications Company (now Boeing Satellite Systems) to build two satellites. The first, MEASAT-1, was launched in January 1996 from the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana, in a ceremony officiated by Mahathir himself.[46] It was positioned in geostationary orbit at 91.5° East and enabled direct-to-home broadcasting, expanded telecommunications coverage, and supported the growth of private broadcasters such as Astro. Later that year, MEASAT-2 was launched to supplement the first satellite, offering additional capacity and coverage. Together, MEASAT-1 and MEASAT-2 played a crucial role in modernizing Malaysia's broadcasting and telecommunications infrastructure during the 1990s.[47]

As part of Mahathir's modernisation and infrastructure development policies, he supported large-scale projects such as the Petronas Twin Towers, which became a landmark in Kuala Lumpur. Serving as the headquarters of the national oil company, Petronas, the 88-storey towers were designed by architect César Pelli. Construction began in 1993 and was completed in 1996. The towers held the title of the tallest buildings in the world from 1998 to 2004 and remain the tallest twin towers globally.[48] The towers were officially opened to the public on 31 August 1999 by Mahathir.[49] Mahathir maintained an office on the 86th floor of one of the towers.[48]

Additionally, Mahathir supported the development of Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA). The project was launched in 1993 based on the government's assessment—under Mahathir's leadership—that Subang Airport was no longer able to accommodate the increasing volume of air passengers. KLIA officially opened on 27 June 1998. Since its inauguration, the airport has been regarded as a world-class international gateway and has received numerous awards from global institutions, including Skytrax and the International Air Transport Association.[50] Another notable project was the Kuala Lumpur Tower (KL Tower), a telecommunications and broadcasting facility that also became a cultural and tourism landmark.[51] Mahathir officiated the installation of the tower's antenna mast on 13 September 1994, marking its final height of 421 meters, and later presided over its official launch on 1 October 1996.[51]

In the 1980s, Mahathir proposed the establishment of a new federal administrative center to decentralise government functions and ease congestion in Kuala Lumpur.[52] In 1993, the Cabinet approved the selection of Prang Besar as the development site,[53] and the area was later renamed Putrajaya in 1994.[54] Mahathir launched the construction of Putrajaya in 1995, with the project projected to be completed by 2005 at an estimated cost of RM20 billion.[55] He officiated the groundbreaking ceremony on 10 September 1996 and declared Putrajaya a city in 1997.[53] On 21 June 1999, Mahathir began working from his new office in Putrajaya, marking the official move of the Prime Minister's Department.[56] In 2001, Mahathir announced that Putrajaya would become Malaysia's third Federal Territory, after Kuala Lumpur and Labuan.[57] The city was once described by the BBC as "one of the world's greenest cities".[58]

Mahathir launched the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) in 1996 as part of his efforts to transform Malaysia into a knowledge-based economy in line with Vision 2020. He officially announced the project at the Multimedia Asia Conference on 1 August 1996, aiming to develop a high-tech zone stretching from the Petronas Twin Towers to Kuala Lumpur International Airport, including Putrajaya and Cyberjaya. To promote the initiative, Mahathir visited the United States in January 1997, where he successfully attracted interest from major IT companies and established an international advisory panel of 30 experts to support the MSC's development.[59] Cyberjaya, developed as the first hub of MSC, has since become known as Malaysia's "Silicon Valley" due to its concentration of tech infrastructure, multinational corporations, and higher learning institutions.[60]

In 2000, Microsoft founder Bill Gates described the MSC in Cyberjaya as the fastest developing IT centre in the world, praising it as one of the most ambitious and committed technology initiatives outside the United States.[61] Mahathir also invested heavily in constructing the Bukit Jalil National Stadium and related facilities to host the 1998 Commonwealth Games.[62] The event was widely regarded as a success,[63] during which Queen Elizabeth II, who officiated the closing ceremony, remarked that she and Prince Philip were deeply impressed with Malaysia's infrastructure development.[64] Commonwealth Games chairman Michael Fennell also declared during the closing ceremony that "Malaysia promised the best ever Commonwealth Games, and Malaysia delivered".[65]

Buy British Last and Look East Policy

In 1981, Mahathir launched the Buy British Last (BBL) policy as a response to the British government's decision to raise tuition fees for foreign students, which disproportionately affected Malaysian scholars in the United Kingdom. At the time, Malaysia had over 17,000 students in the UK, and the removal of subsidies placed a significant financial burden on the government. When Mahathir's appeal for reinstating subsidies was rejected by the Margaret Thatcher administration, Malaysia retaliated by limiting imports from British companies, publicly discouraging British goods and services unless deemed absolutely necessary.[66]

The Buy British Last campaign was part of Mahathir's broader vision to reduce Malaysia's reliance on the West and assert greater national autonomy. In line with this approach, he introduced the Look East Policy (LEP) in 1982, which encouraged Malaysians to adopt the work ethic and development model of East Asian nations, particularly Japan and South Korea. The policy involved sending Malaysian students and trainees to Japan for education and industrial training, while also inviting Japanese professionals to contribute to Malaysia's development. Mahathir was deeply impressed by Japan's post-war recovery and industrial discipline, which he saw as a model for Malaysia's own modernization efforts.[66] He also noted in his speech at the 20th Anniversary of the Look East Policy in 2002 that nations had looked to Japan for inspiration even prior to the policy's formal launch, citing the Meiji Restoration and Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War as pivotal moments that encouraged many Asian countries to resist Western colonial domination.[67] In 2022, during the 40th anniversary of the Look East Policy, Mahathir said the policy had been largely successful, noting that over 26,000 Malaysians had been sent to Japan since 1982 and nearly 1,500 Japanese companies were operating in Malaysia, employing more than 400,000 Malaysians.[68]

Health policy

In 1983, Mahathir announced a shift in health policy as part of a broader economic strategy emphasising private sector growth. The government began promoting the expansion of private healthcare and initiated studies on alternative financing methods, including insurance-based models. In 1985, the first official study on health financing reform was commissioned under his administration. Over the following two decades, private sector involvement in healthcare increased significantly. The number of private hospitals grew from 50 in 1980 to 224 by 2000, and the out-of-pocket share of national health expenditure rose steadily.[69]

Reforms during Mahathir’s tenure included the corporatisation of Hospital Kuala Lumpur’s cardiac unit into the National Heart Institute (IJN) in 1992,[69] following his heart attack in 1989, which prompted efforts to improve cardiac care in Malaysia.[70] Other measures included the contracting out of drug distribution in 1994, and the outsourcing of hospital support services in 1996.[69] In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO) presented Mahathir with an award for his contributions to primary health care in Malaysia.[71]

Drug policy

Upon assuming office as prime minister, Mahathir identified drug abuse as the primary public enemy of the nation.[72] Shortly after taking office, he stressed that the misuse and abuse of drugs were socially destructive, and that governments bore a heavy responsibility to prevent drug abuse from harming societies and leading the younger generation into irresponsibility and social deviance.[73]

Malaysia introduced the death penalty for offences such as murder and drug trafficking in 1975, initially as a discretionary punishment.[74] During Mahathir's administration, the death penalty for drug trafficking was made mandatory in 1983, reflecting the government's hardline stance against drug-related crimes at the time.[74] The media has described Malaysia as having some of the world's toughest drug laws, including a mandatory death penalty for those convicted of trafficking 15 grams (0.5 oz) or more of heroin or morphine, 1,000 grams (2.2 lbs) of opium, or 400 grams (14 oz) of cannabis.[75]

Under Mahathir's leadership, the government also implemented other anti-drug measures, including strengthening border control and launching large-scale public education campaigns. Anti-drug stories appeared regularly in the newspapers, and public service announcements became a common feature on television. The establishment of the Anti-Narcotics Committee and its executive arm, the Anti-Narcotics Task Force, in 1983 was a key part of these efforts. The committee, chaired by the prime minister and accountable to the National Security Council, was empowered by legislation passed in 1985, which allowed the government to detain suspected drug syndicate leaders without trial.[76]

According to data from Amnesty International, Malaysian authorities executed over 120 prisoners convicted of capital drug offenses between 1983 and 1992, with at least 39 executions in 1992, the highest annual total ever recorded by Amnesty International in Malaysia.[77] Notable cases include the execution of Kevin Barlow and Brian Chambers, two Australian nationals in 1986, who became the first Westerners to be sentenced to death in Malaysia. Last-minute appeals for clemency from Australian prime minister Bob Hawke, British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, and Amnesty International were unsuccessful, with Hawke condemning the hangings as "barbaric", and Mahathir responding, "You should tell that to the drug traffickers".[78] In May 1990, eight Hong Kong citizens were hanged in Malaysia, marking the largest mass execution for drug offenses in the country's history.[79]

Due to the anti-drug policies, Malaysia's drug-related incidents decreased from 14,624 cases in 1983 to 7,596 cases in 1987, and the number of foreign nationals apprehended for drug trafficking also declined.[80] In 1987, Mahathir was elected as the President of the International Conference on Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking,[81] where he chaired the plenary session.[82] During the discussions on two working papers, one on guidelines for combating the drug menace and the other on the declaration against drugs, 138 nations provided overwhelming support.[82]

Constitutional amendments and weakening of royal powers

Under Malaysia's federal and state constitutions, the Malay Rulers are bound by Westminster-style conventions, with the King generally expected to act on the advice of the executive. This arrangement had functioned relatively smoothly—until Mahathir became prime minister and the federal government began to take action against certain rulers who flouted the law and lived lavishly at public expense.[83]

In 1983, Mahathir introduced a series of constitutional amendments aimed at limiting the powers of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. Among the proposed changes were the imposition of a 30-day limit for the monarch to veto legislation and a restriction on the King's authority to declare a state of emergency. The proposals were met with significant resistance from the Malay rulers, prompting Mahathir's government to launch a public campaign to pressure the monarchy into accepting the changes. Eventually, a compromise was reached, and a revised amendment was passed, restoring the King's right to declare emergencies and allowing up to 60 days to delay legislation, but royal assent was no longer required for the enactment of laws.[84]

In 1993, another constitutional crisis unfolded following an alleged assault by the Sultan of Johor on hockey coach Douglas Gomez.[84] Up until then, the rulers had enjoyed absolute personal immunity from proceedings in any civil or criminal court. On 6 December 1992, Maktab Sultan Abu Bakar Johor hockey coach Douglas Gomez lodged a police report alleging that he was beaten by the then Sultan of Johor, Sultan Iskandar Sultan Ismail.[85] Responding to the report, Mahathir had said: "The royalty is not above the law. They cannot kill people. They cannot beat people." Four days later, on 10 December, the Dewan Rakyat held a special session and passed a motion to curb the powers of the royalty if necessary. The motion received 96 votes from the 180 lawmakers, including two votes from PAS and DAP. It was the first time a reproach against the monarchy was accepted by the Dewan Rakyat.[86]

The then Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Ghafar Baba subsequently moved a bill to amend the Constitution to make the rulers liable to criminal and civil proceedings in ordinary courts. The motion stated that "all necessary action must be taken to ensure that a similar incident" would not recur. Semangat 46, led by Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, opposed the motion, arguing it would undermine royal authority and Malay privileges.[86]

During this period, page 2 of the government-controlled New Straits Times regularly featured reports exposing royal excesses. Sultan Ismail Petra of Kelantan, for instance, was said to have imported 30 duty-free luxury cars—far exceeding the permitted seven—and once evaded customs officials in a Lamborghini Diablo by claiming he was test-driving it. The paper highlighted the RM200 million cost of maintaining the rulers, including exclusive hospital wards and RM9.3 million spent on new cutlery and bedspreads for the King—enough, it noted, to build two hospitals, 46 rural clinics, or 46 primary schools.[87]

On 19 January 1993, following a two-day special sitting, the Dewan Rakyat overwhelmingly passed the Constitution (Amendment) Bill 1993 with 133 votes in favour, aiming to remove the legal immunity of the Malay Rulers.[88] However, the sultans refused to comply, arguing that the constitution clearly prohibited the government from enacting laws affecting them without their consent.[89] In a joint statement condemning Parliament's move, the rulers asserted that they had always played a vital constitutional role—particularly in securing independence, shaping the federal constitution, and preserving Malay unity.[89] In March 1993, a compromise bill was introduced with several key concessions: no civil or criminal action could commence against the royalty in their personal capacity except with the attorney-general's consent under Article 183; rulers were permitted to initiate civil proceedings; all such cases would be tried under a Special Court established under Articles 181(2) and 182; and the Conference of Rulers would nominate two out of five judges to the Special Court under Article 182(1). If convicted, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, rulers, and their consorts could be pardoned by the Conference of Rulers under Article 42(12)(b). These reforms were eventually accepted by a majority of the Conference of Rulers, formalising the Special Court system.[86] The first notable case under the new system occurred in October 2008, when the court ordered the then Yang di-Pertuan Besar of Negeri Sembilan to pay US$1 million to a bank in a civil suit.[90]

Further reforms followed in 1994 when the government amended the constitution to ensure that any law passed by Parliament would automatically become law within 30 days, regardless of whether the King gave assent.[86] These three episodes marked a significant shift in the balance of power between the monarchy and the executive, with Mahathir consolidating civilian authority over royal prerogatives. His administration was the first to successfully curtail the discretionary powers of the Malay rulers in post-independence Malaysia.[84]

Defence

Under Mahathir's leadership, Malaysia undertook significant military modernisation efforts. As minister of defence from 1981 to 1986, he played a key role in shaping the country's defense strategy. His administration oversaw the procurement of advanced military assets, including 18 Russian-made MiG-29N fighter jets and eight American-made F/A-18D Hornets, diversifying Malaysia's defense partnerships beyond traditional suppliers. Malaysia also explored the purchase of submarines, with plans to acquire British Oberon-class submarines in 1988, although the deal was later canceled. Additionally, Mahathir strengthened Malaysia's defense ties with various countries, including Poland, Brazil, India, and Pakistan, expanding the range of military equipment procurement.[91]

A major structural reform during Mahathir's leadership was the establishment of the 10th Parachute Brigade (10 Briged Para) in 1994 as a Rapid Deployment Force (Pasukan Aturgerak Cepat). Internationally, Malaysia became a key contributor to United Nations peacekeeping missions, deploying around 18,000 military and police personnel between 1998 and 2003. The country's active participation peaked between 1992 and 1996, with about 2,500 peacekeepers sent to Cambodia, Bosnia, and Somalia. In recognition of Malaysia's commitment, the Malaysian Peacekeeping Training Centre (MPC) was established in Port Dickson in 1996, following an agreement with the UN to provide personnel for peacekeeping missions at any time.[91]

Haze pollution issue

During Mahathir's first tenure as prime minister, transboundary haze pollution emerged as a serious regional concern, with severe episodes beginning in the early 1990s and peaking in 1997. The haze, caused primarily by forest fires in Indonesia, posed significant environmental and health risks across Southeast Asia. In response to the 1997 crisis, the Malaysian government declared a state of emergency in Sarawak and several cities in Peninsular Malaysia. Mahathir's administration deployed 2,000 firefighters, the SMART disaster relief team, and Royal Malaysian Air Force units for cloud seeding operations in affected areas. He also established a disaster management committee, introduced policies on disaster and haze control, and reactivated the National Haze Action Plan. Mahathir publicly warned 17 Malaysian plantation companies operating in Indonesia to extinguish fires on their concessions or face repercussions.[92] On 11 December 1997, Malaysia and Indonesia signed a memorandum of understanding to jointly address transboundary haze issues through information exchange, joint training, and public awareness efforts.[93][92] These bilateral efforts contributed to the eventual signing of the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution in Kuala Lumpur on 10 June 2002.[94][92]

Remove ads

Foreign policy

Summarize

Perspective

In foreign policy, Mahathir advocated for diversifying Malaysia's international relations by actively exploring non-traditional and lesser-known markets, believing that a trading nation should not rely solely on established partners.[95] By 1999, Malaysia's trade with small and weak countries of the South had generated RM90 billion in volume annually since the Government initiated approaches in this direction.[96] Mahathir prioritised economic diplomacy over ideological alignment. He instructed Malaysian diplomats to focus on trade and investment opportunities.[97]

He turned to East Asia, promoting the "Look East Policy" and proposing the formation of the East Asia Economic Caucus (EAEC) to deepen regional economic integration. While initially facing resistance, the idea laid the foundation for the ASEAN Plus Three framework, which was formalised in 1999.[98]

Mahathir also pursued broader South–South cooperation, strengthening ties with Muslim-majority countries through platforms such as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the Developing Eight (D-8). His administration encouraged economic collaboration with these nations, including through the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) using Islamic finance instruments such as mudarabah.[98]

United States

Although Mahathir was a strident critic of U.S. foreign policy during his tenure, American investment in Malaysia nevertheless boomed.[99] After becoming prime minister, Mahathir declined the American ambassador's suggestion to meet the U.S. president, saying it was not in his plans, and only visited the United States three years later in 1984 while he was in North America.[100] Mahathir said that his visit aimed to raise awareness of Malaysia among Americans and to encourage greater investment and trade ties with the United States.[101] During his first visit, Mahathir received a warm welcome with full presidential honours, including transport by Air Force and Marine One, and met with President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office as well as Vice President George H. W. Bush.[102] He held discussions with Reagan on bilateral relations, global economic recovery, and regional security, with both sides expressing a high degree of agreement and a commitment to strengthening cooperation, especially in trade and economic matters.[103]

The U.S., while occasionally at odds with Mahathir’s outspoken rhetoric, often prioritised strategic and economic considerations in its dealings with Malaysia. For example, the Clinton administration chose not to penalise Malaysia under the 1996 Helms-Burton Act after its state-owned Petronas signed a US$2 billion deal with Iran, citing American national interests.[104]

Mahathir was described as a strong U.S. ally in the war on terror but also a vocal critic of the Iraq War.[105] In May 2002, Mahathir met with President George W. Bush in Washington, D.C., where they signed a memorandum of understanding on counterterrorism.[106] In March 2003, he condemned the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq as imperialistic and a violation of international law, warning it would provoke widespread resentment, fuel terrorism, and undermine global respect for democracy and sovereignty;[107] Mahathir also tabled a parliamentary motion containing seven resolutions against the war, which received unanimous support, including from opposition parties.[108]

Indonesia

Mahathir and former Indonesian president Suharto were close friends, frequently visiting each other during their respective tenures as national leaders.[109] He made an official visit to Indonesia less than a month after taking office.[110] In a joint communiqué issued after talks with Suharto, both countries urged the withdrawal of Vietnamese troops from Cambodia and called for a political solution in Afghanistan.[111]

During his tenure, Malaysia and Indonesia significantly expanded their bilateral economic cooperation, particularly in the sectors of investment and trade. Cooperation was notably strong in the plantation sector, with Malaysian companies investing heavily in palm oil and rubber plantations across Indonesia, including in Riau, Kalimantan, and Irian Jaya.[112]

To facilitate and protect bilateral investments, both countries signed several agreements:

- A Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement on 22 January 1991, aimed at eliminating the double taxation of income such as business profits, dividends, and royalties, thereby enhancing cross-border trade and investment flows.

- An Investment Guarantee Agreement (IGA) on 22 January 1994, designed to protect investors from non-commercial risks such as expropriation and to ensure the free transfer of profits and capital between the two countries.[112]

Mahathir also played a role in promoting regional subnational economic zones that included Indonesia, such as:

- The Indonesia–Malaysia–Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT), proposed in 1993, which focused on economic cooperation between northern Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia, and southern Thailand.

- The SIJORI Growth Triangle involving Singapore, Johor, and the Riau Islands, which promoted economic integration across complementary sectors.

- The Brunei Darussalam–Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA), established in 1994, which aimed to develop less-developed territories in Borneo and eastern Indonesia.[112]

In 1997, Mahathir and Suharto jointly proposed the Malacca Strait Bridge, a megaproject intended to physically connect Peninsular Malaysia with Sumatra,[113] although the plan was never realised.[112]

Despite the strong economic ties, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis posed serious challenges. Many Malaysian firms scaled back or suspended operations in Indonesia, and land disputes emerged as Indonesian workers and locals reclaimed plantation lands previously held by Malaysian companies. However, Mahathir and the Indonesian leadership worked to stabilise and rebuild economic relations in the post-crisis period.[112]

In March 2000, Mahathir made a two-day official visit to Indonesia,[114] during which both countries signed eight memoranda of understanding covering sectors such as banking, infrastructure, information technology, air services, and oil and gas.[115] In response to Indonesia’s interest in Malaysia’s New Economic Policy (NEP), the Malaysian government invited Indonesian officials to study its implementation.[116] Mahathir was the second ASEAN leader to visit Indonesia following the election of President Abdurrahman Wahid, who received him upon arrival in Jakarta.[117]

On 28 August 2003, Mahathir met with Indonesian president Megawati Sukarnoputri in Kuching, where they discussed efforts to combat terrorism and address the continued influx of Indonesian undocumented migrants into Malaysia;[118] following the meeting, Mahathir announced that both countries had agreed on a range of strategies to curb the entry of Indonesian illegal immigrants.[119] In the same year that Mahathir was due to retire, during the ASEAN Summit in Bali, Megawati paid tribute to Mahathir ahead of his retirement, describing him as a steadfast friend and influential ASEAN leader;[120] Mahathir responded by expressing gratitude and reaffirming Malaysia's commitment to ASEAN.[121] Following this, media reports stated that Megawati was "in tears" at the summit due to her emotional tribute to Mahathir.[122]

United Kingdom

Shortly after taking office, Mahathir's administration experienced growing diplomatic tension with the United Kingdom. In September 1981, Malaysia’s state investment arm, Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB), executed a surprise acquisition—commonly referred to as the "Dawn Raid"—on the London Stock Exchange to obtain control of Guthrie Corporation, a major British plantation company. In the week that followed, the United Kingdom’s Securities Industry Council amended its regulations governing large share acquisitions and corporate takeovers. Although British officials stated that the amendments had been under consideration for months, the timing prompted speculation within Malaysia that the changes were a direct response to the raid.[123]

On 2 October 1981, Mahathir confirmed that the Cabinet had adopted a new policy requiring all federal ministries, departments, and statutory bodies to seek non-British alternatives when procuring goods or consultancy services. Any proposal involving British firms would now be reviewed by the Prime Minister’s Department for approval. The directive also applied to joint ventures and partially British-owned companies. While Mahathir declined to publicly explain the rationale, the decision was widely interpreted as a reaction to perceived British hostility and regulatory retaliation. The policy, known as "Buy British Last", was declared official federal policy, with state governments being informed accordingly.[123] British Trade Minister Peter Rees, who had been visiting Kuala Lumpur at the time, expressed surprise at the announcement and remarked that it did not align with the tone of his earlier discussions with Malaysian officials.[124]

British companies were estimated to have lost approximately £15.5 million within the first few months of the campaign.[125] Anthony Kershaw, chairman of the British House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, estimated total losses to be between £20 million and £50 million.[125] In an effort to ease tensions caused by the campaign, Mahathir visited London in 10 March 1983 and met British prime minister Margaret Thatcher at 10 Downing Street.[126] The next day, he acknowledged shifts in British attitudes and indicated that Malaysia might review its policy towards Britain.[127] The campaign was officially withdrawn shortly thereafter.[128]

In 1984, the status of Carcosa, a colonial-era residence gifted to the British government by Tunku Abdul Rahman in 1956, became a source of diplomatic and political attention. Following a resolution at the UMNO General Assembly, UMNO Youth leader Anwar Ibrahim called for the property's return, arguing that independence should not have entailed material concessions. Mahathir supported the initiative, stating that the government needed to consider the sentiments expressed by UMNO.[129] In May 1984, Mahathir announced that the British government had agreed to return Carcosa to Malaysia in exchange for a parcel of land in the Ampang diplomatic enclave, with no other compensation to be paid and the mansion to be repurposed as a guest house for state visitors.[130] The formal handover, however, was only finalised in 1987 following sustained pressure from the Malaysian government.[131]

In April 1985, Mahathir met with Thatcher during her official visit to Malaysia—the first by a British prime minister. During their meeting, Mahathir discussed British investment, trade liberalisation, and ASEAN's access to European markets. The visit also resulted in the resolution of a long-standing aviation dispute: the British government granted Malaysian Airline System a fifth weekly landing slot at Heathrow Airport, while Malaysia agreed to reconsider a tax concession seen as favoring MAS.[132] Later that year, Mahathir attended his first Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Nassau.[133]

During his tenure, Malaysia hosted two major Commonwealth events attended by Queen Elizabeth II: the 1989 CHOGM in Kuala Lumpur and the 1998 Commonwealth Games, the first to be held in Asia. These visits reflected Malaysia’s growing engagement within the Commonwealth and marked the country's expanding diplomatic and economic profile in the international arena.[134]

Soviet Union/Russia

On 29 July 1987, following visits to the United Kingdom and Hungary, Mahathir began an official visit to the Soviet Union, where he was received at the airport in Moscow by Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze.[135] During his meetings with Soviet officials, including a two-hour bilateral discussion with Soviet Communist Party Secretary-General Mikhail Gorbachev at the Kremlin, both sides agreed to strengthen bilateral ties through regular high-level consultations and increased economic cooperation. They affirmed support for peaceful dispute resolution and endorsed Southeast Asia as a zone of peace, freedom, and neutrality. Discussions also covered Kampuchea, Afghanistan, the Iran–Iraq War, and disarmament. Mahathir raised concerns about the Soviet stance on Antarctica, leading to an agreement for further dialogue between foreign ministers.[136]

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Mahathir continued to strengthen Malaysia–Russia relations throughout the 1990s. Economic cooperation deepened, particularly in defense procurement, with Malaysia purchasing 18 MiG-29 fighter jets from Russia in 1995, contributing to a record bilateral trade volume of US$827.6 million that year.[137]

In 1998, following a meeting with Khabarovsk Krai Head of Administration Viktor Ishayev in Kuala Lumpur during the APEC summit, Mahathir abolished the visa requirement for Russians from the region for visits of up to one month.[137]

In August 1999, Mahathir visited the Russian Far East region of Khabarovsk Krai, where he met with local officials and emphasised the importance of fostering regional-level cooperation. He noted that due to Russia’s vast size, bilateral relations should not be limited to Moscow alone. Impressed by Khabarovsk's economic potential, he expressed interest in increasing Malaysian imports from the region and finding new markets for Malaysian exports, particularly fruits. He highlighted the need to address transportation and logistics costs to boost two-way trade. Mahathir also proposed promoting cultural exchanges among the younger generations to strengthen mutual understanding between the two countries.[137] Subsequently, he visited the Republic of Buryatia in Russia at the invitation of its president Leonid Potapov, becoming the first foreign head of government to do so, where he explored cooperation in aero-defence technology, mining, and timber processing.[138]

Since Vladimir Putin assumed the presidency of Russia, Mahathir met with him on multiple occasions. These included meetings during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Brunei in 2000 and again at the 2001 APEC summit in Shanghai. Mahathir had planned to make an official visit to Moscow in September 2001, but the trip was postponed following the September 11 attacks.[139] Following Mahathir’s official visit to Russia in March 2002,[140] Malaysia and Russia agreed to establish a Joint Economic Commission as well as the Malaysia-Russia and Russia-Malaysia Business Councils to follow up on decisions made during the bilateral meetings held in Moscow.[141]

Putin visited Malaysia twice in 2003 — first on an official trip in August, and later in October to participate in the OIC Summit.[142] The August visit saw Putin confer the Order of Friendship on Mahathir and both leaders witness the signing of a major defence contract for 18 Su-30MKM fighter jets, along with agreements on scientific and technical cooperation and information and communications technology.[143] According to Viktor Kladov, a senior official from Rostec and a special envoy of Putin, Putin held Mahathir in high regard and expressed strong respect for his leadership, viewing him as a figure capable of propelling Malaysia towards becoming a great nation. Putin also valued Mahathir’s longstanding efforts, particularly since the early 1990s, in developing Malaysia’s aerospace and defence sectors, including the establishment of the Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition (LIMA).[144]

Japan

On 15 December 1981, Mahathir introduced the Look East Policy, identifying Japan as a model for development, and in 1983, during his visit to Japan, the policy received its first high-level endorsement when Mahathir and Foreign Minister Shintaro Abe formally affirmed bilateral cooperation.[145] After 1982, relations between the two countries further deepened.[146] Following the 1985 Plaza Accord, the appreciation of the yen prompted Japanese companies to shift production overseas to lower costs, while Malaysia, facing a commodity crisis, adopted an export-oriented industrialisation policy—attracting substantial Japanese investment and boosting bilateral trade and official development assistance.[146]

Under Mahathir’s leadership, Japan emerged as Malaysia’s second-largest trading partner. Between 1997 and 2002, Malaysia recorded 643 Japanese investment projects valued at RM11.4 billion. Mahathir also secured low-interest Official Development Assistance (ODA) loans from Japan, supporting infrastructure and industrial development.[97]

Mahathir maintained close ties with a number of Japanese prime ministers and political figures. Among them were former prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, with whom he collaborated on initiatives such as the East Asia Economic Caucus, and former Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara, with whom he co-authored the book The Asia That Can Say No.[147]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

During the Bosnian War, Mahathir was a vocal supporter of Bosnia,[148] and Malaysia accepted and granted asylum to Bosnian Muslim refugees.[149] In May 1992, Kuala Lumpur officially recognised Bosnia and Herzegovina, along with Croatia and Slovenia, as independent nations. Bosnia and Herzegovina, in turn, established its embassy in Kuala Lumpur two years later.[150] In 1994, Mahathir strongly condemned ethnic cleansing and the inaction of the international community, declaring that 'ethnic cleansing of Bosnia-Herzegovina must be stopped or forever must those who mouth platitudes about democracy and human rights cease and desist from their pretense at righteousness'.[151] In June 1995, he ordered Malaysian UN peacekeepers not to surrender and openly criticised the United Nations for its indecision and failure to protect civilians.[151] Subsequently, Malaysia became the first country to openly declare its willingness to break the United Nations arms embargo on Bosnia, with Mahathir announcing that Malaysia would supply weapons to the Bosnian government in defiance of the embargo, while criticising the UN and NATO for enabling Serbian aggression against Bosnian Muslims.[152]

Following the end of the war with the signing of the Dayton Agreement in December 1995, Malaysia contributed to Bosnia's post-war reconstruction. The Bosmal Business Center in Sarajevo, built by Bosmal—a joint venture between Malaysian and Bosnian entities—was the tallest building in Bosnia until 2008. Mahathir stayed there during his visits to Sarajevo. Additionally, the Malaysian-Bosnian Friendship Bridge in Sarajevo, inaugurated by Mahathir himself, serves as a symbol of the ties between the two nations.[150]

In 2007, Mahathir was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by four Bosnian civil groups led by former president Ejup Ganić, in recognition of Malaysia’s political, economic, and humanitarian support for Bosnia during and after the Bosnian War.[153] In addition, a monument honouring Mahathir was unveiled in Sarajevo’s Kemal Monteno Park to acknowledge his and Malaysia’s contributions during the conflict and post-war reconstruction; the monument was completed in 2020.[154]

Remove ads

Elections

Summarize

Perspective

UMNO leadership elections

1987 UMNO leadership election

In 1987, Mahathir faced a serious challenge to his leadership when Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah contested the UMNO presidency, supported by former deputy Musa Hitam. Mahathir, backed by most party elites and the media, narrowly retained his position. Razaleigh's faction disputed the outcome, leading to legal battles that resulted in the courts declaring UMNO illegal in 1988.[155][156] Mahathir quickly formed UMNO Baru, sidelining his rivals who later formed Semangat 46 under Razaleigh.[157]

Malaysian general elections

1982 Malaysian general election

On 22 April 1982, Malaysia held a general election that had been called 16 months early by Mahathir. The ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) secured 131 of 154 parliamentary seats as final landslide results came in from East Malaysia.[159] The victory was attributed to Mahathir and Musa Hitam's popularity, effective campaigning, and strategic candidate selection.[160]

1986 Malaysian general election

On 2 August 1986, Malaysia held a general election in which the ruling BN coalition, led by Mahathir, won 148 out of 177 parliamentary seats, securing a two-thirds majority. The strong mandate further consolidated Mahathir's leadership.[161]

1990 Malaysian general election

On 21 October 1990, Malaysia held its eighth general election, in which Mahathir secured a third term with a landslide victory. His BN coalition won 121 out of 180 parliamentary seats, retaining a two-thirds majority. However, the opposition alliance led by Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah won all 39 state seats in Kelantan.[162]

1995 Malaysian general election

On 24 April 1995, Malaysia held its ninth general election. The ruling BN, led by Mahathir, won a landslide victory by securing 162 out of 192 parliamentary seats, significantly increasing its majority from 125 seats in the previous term. The opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP) saw its representation reduced from 20 seats to just 9. The election was widely regarded as a personal triumph for Mahathir, who campaigned on his Vision 2020 agenda to transform Malaysia into a fully developed nation. The result also reinforced his position within the ruling coalition.[163]

1999 Malaysian general election

On 29 November 1999, Malaysia held its tenth general election. The ruling BN coalition, led by Mahathir, won 149 out of 193 parliamentary seats, securing more than a two-thirds majority.[164] Mahathir, at a press conference after the victory, said that the result was a clear indication that "the Barisan Nasional is still the party of choice of the people of Malaysia".[165] The election reaffirmed his leadership and the coalition's strong mandate,[166] while the opposition DAP suffered significant losses, including the defeat of senior leaders such as Secretary-General Lim Kit Siang and Vice Chairman Karpal Singh.[167]

1981–2003 Malaysian by-elections

Additionally, Mahathir had a 16 to 9 win–loss record in parliamentary by-elections while leading the ruling coalition, representing a 64 percent success rate. In one instance, Lipis in 1997, the BN coalition won uncontested. Across the 24 contested by-elections during his leadership, the ruling coalition averaged 54.37 percent of the vote share.[168]

Remove ads

Personal leave

Summarize

Perspective

In September 1981, shortly after becoming prime minister, Mahathir took a two-week private vacation to Spain and Portugal, stating that the trip was strictly personal and involved no official meetings.[169] In September 1983, Mahathir announced that he would take a two-week personal leave starting, during which he would travel to Europe for a holiday with his family. Speaking to reporters, he remarked, "I am only human. But although I am entitled to two months' holiday a year, I am only taking two weeks off."[170] Following a coronary bypass surgery in January 1989, Mahathir took a three-week vacation abroad to London, Spain, and Morocco, before returning to work on 4 April.[171]

On 19 May 1997, Mahathir began a two-month leave of absence,[172] during which Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim was appointed as acting prime minister.[173] He dismissed speculation that the leave was due to health reasons, stating that he would continue to carry out certain official duties during his time off.[174] During the vacation, Mahathir also denied that Anwar’s appointment as acting prime minister was part of a succession plan, though he acknowledged that he would eventually have to step down.[175] Despite being on leave, Mahathir remained active on the international stage. He promoted the Multimedia Super Corridor in the United Kingdom, attended a summit of eight Islamic developing countries in Istanbul, became the first Malaysian prime minister to make an official visit to Lebanon, and held bilateral talks in Hungary with Prime Minister Gyula Horn. Mahathir also participated in an UMNO Supreme Council meeting via video conference from London. His continued presence in foreign media and official engagements countered speculation that the extended leave signaled a retreat from political leadership.[176]

In January 2000, Mahathir left for a two-week vacation in Argentina and the Caribbean, followed by a week-long working visit to Davos, Switzerland.[177]

In late June 2002, following his announcement of resignation during the UMNO General Assembly, Mahathir took a 10-day personal leave in Italy.[178] During this period, Deputy Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi served as acting prime minister, and Mahathir had already handed over some of his Ministry of Finance responsibilities to Abdullah in the preceding weeks.[179] On 3 July, he returned to Malaysia and was greeted by a crowd of approximately 5,000 people at the Royal Malaysian Air Force base in Subang, including government officials, students, and supporters.[178]

In March 2003, Mahathir began a two-month leave of absence, during which Abdullah served as Acting Prime Minister and Acting Finance Minister.[180] He commenced his vacation after attending the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) emergency summit in Doha, departing from the city with his wife, Siti Hasmah Mohamad Ali.[181] During the leave, he also made a two-day official visit to Brazil, his second visit to the country after a previous trip in 1991.[182] Mahathir returned to Malaysia on 2 May after a two-month vacation abroad and resumed official duties a few days later.[183]

Remove ads

Retirement and succession

Summarize

Perspective

In May and June 2002, Mahathir made visits to the United States and the Vatican, respectively.[184][185] On 22 June 2002, Mahathir unexpectedly announced his resignation during the UMNO general assembly.[186] However, the decision was retracted less than an hour later following emotional appeals from his colleagues and supporters.[186] On 26 June, the secretary-general of UMNO, Mohd Khalil Yaakob, announced that Mahathir's resignation would take effect only after the Organisation of Islamic Conference Summit in Kuala Lumpur in October 2003,[187] stating that the reins of government would then pass to his deputy, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi.[188]

On 31 October 2003, as Mahathir step down after 22 years in office,[189][190] hundreds of tribute messages appeared in Malaysian newspapers in the weeks leading up to his retirement, hailing him as a national hero for overseeing Malaysia's rapid economic development and for giving the country a stronger voice on the global stage. A 10-volume encyclopedia of his ideas was launched in both Arabic and English. His successor, Abdullah, said that Mahathir's legacy would be reflected in "an ever-flowing cornucopia of ideas, thoughts and opinions on a wide range of issues and topics", and added that "laymen and intellectuals will find pearls of wisdom in his ideas and thoughts", while also noting that "Malaysians and Muslims will benefit enormously from reading and re-reading his speeches".[191]

Following his retirement as prime minister, Mahathir and his wife, Siti Hasmah, were both conferred the Seri Maharaja Mangku Negara (S.M.N.), the nation's highest federal award, which carries the honorific title "Tun".[192] In recognition of Mahathir's contributions to the nation, the government under Abdullah conferred upon him the title Bapa Pemodenan Malaysia (Father of Malaysia's Modernisation).[193] As part of the tribute, Galeri Sri Perdana—the former official residence of Mahathir prior to his move to Putrajaya—was reopened as a national gallery highlighting his life and tenure as Malaysia's longest-serving prime minister.[194][195]

Remove ads

See also

References

Sources

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads