Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Fitzpatrick Court

Period of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1906 to 1918 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

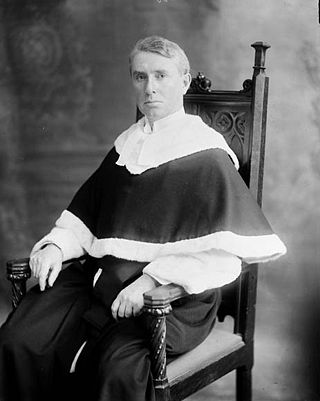

The Fitzpatrick Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1906 to 1918, during which Charles Fitzpatrick served as Chief Justice of Canada. Fitzpatrick succeeded Henri Elzéar Taschereau as Chief Justice after the latter's resignation, and held the position until his retirement on October 20, 1918.

The Fitzpatrick Court, much like all iterations of the Supreme Court prior to 1949, was largely overshadowed by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which served as the highest court of appeal in Canada, and whose decisions on Canadian appeals were binding on all Canadian courts.

The Fitzpatrick Court continued to face many of the same criticisms as its predecessors, the Ritchie Court, Strong Court and Taschereau Court, including the concerns about the conduct of its justices and the partisan nature of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier's appointments, which by 1911 accounted for the entire bench. The Court also became increasingly political, with justices providing advice and taking on quasi-judicial roles for both the Laurier and Borden governments.

Remove ads

Membership

Summarize

Perspective

The Supreme Court Act, 1875 established the Supreme Court of Canada, composed of six justices, two of whom were allocated to Quebec under law, in recognition of the province's unique civil law system.[1][2][ps 1] Early appointments to the Court reflected an unwritten regional balance, with two justices from Ontario and two from the Maritimes.[3][4] Western Canada was not represented until the early 1900s.[5]

Chief Justice Henri-Elzéar Taschereau resigned on May 2, 1906, at the age of 69.[6] He claimed his resignation was a condition of his 1904 appointment to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.[6] He remained in office until the Laurier government named a successor. By his retirement, Taschereau had served 44 years as a judge, including over 27 years on the Supreme Court. In his final years, his health and energy had declined.[6]

Charles Fitzpatrick was appointed Chief Justice of Canada by Prime Minister Laurier on June 4, 1906. An Anglo-Quebecer and Catholic, he had served as a Liberal Member of Parliament and Minister of Justice.[7] In his legal career, he worked as both Crown counsel and criminal defence, representing several prominent clients, including Louis Riel (1885), Thomas McGreevy (1891), and Honoré Mercier (1893).[7][8] Fitzpatrick was the first person since William Buell Richards to be appointed directly to the position of Chief Justice, and the only one to do so without prior judicial experience.[7] Contemporary public reaction was positive, likely due to his prominent legal work earlier in his career.[7][8]

Justices from the Taschereau Court who continued into the Fitzpatrick Court included Robert Sedgewick of Ontario, Désiré Girouard of Quebec, Louis Henry Davies of Prince Edward Island, John Idington of Ontario, and James Maclennan of Ontario.[9]

On September 27, 1906, Wilfrid Laurier appointed Lyman Duff of British Columbia to the Court following the death of Justice Sedgewick on August 4, 1906. Duff, then 41, was appointed from the Supreme Court of British Columbia, and was the first appointment from British Columbia. An active Liberal in Victoria, he had served as junior counsel on the Alaska Boundary Commission, and was a justice of the British Columbia Court for two years before his appointment.[10] Duff's appointment was well received by the legal community due to his good reputation and name recognition across Canada.[11] Duff went on to become the longest serving justice in the Court's history, serving for over 37 years, including 10 years as Chief Justice. Historians Snell and Vaughan note that by the 1980s, Duff was the "most famous justice in the history of the [Court]."[7]

On February 23, 1909, Laurier appointed Francis Alexander Anglin of Ontario after Justice Maclennan's retirement on February 13. Anglin had joined the High Court of Justice of Ontario (Exchequer Division) in 1904 after 16 years in corporate and commercial practice.[12] Considered a "scientific" lawyer, he had written several articles and a book before his appointment.[13]

On August 11, 1911, Laurier appointed Louis-Philippe Brodeur of Quebec after the death of Justice Girouard on March 22. Brodeur, a Liberal MP since 1891, had served as Speaker of the House of Commons of Canada and held minor cabinet roles in the Laurier government, including Minister of the Naval Service and Marine and Fisheries.[12] He was well liked and a close friend of Laurier, though described as having shown "no great skill in politics or law."[12]

By 1912, with Girouard's retirement, the entire Court consisted of Laurier appointees. His government followed two contrasting approaches to appointments: some, such as Justices Armour, Killam, Duff, and Anglin, were chosen for their skill and merit; others were patronage appointments to reward Liberals, often with limited judicial or legal experience.[12] Historians Snell and Vaughan note that justices such as Davies, Fitzpatrick, and Brodeur, who came from elected office, lacked the well-developed legal reasoning expected of judges and did not "make as useful a contribution to the law" as their more qualified colleagues.[12]

Timeline

Thompson appointee Bowell appointee Laurier appointee

Remove ads

Other branches of government

The Fitzpatrick Court began during the 10th Canadian Parliament, under a majority government led by Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier.[14]

The Court's tenure overlapped with three general elections. In 1908, the Liberal Party was re-elected with a majority government.[14] In 1911, the Conservative Party, led by Robert Borden, won a majority and formed the government.[14][15] In the contested 1917 election, which saw the Liberal and Conservative parties split into two coalitions, Robert Borden remained Prime Minister when his Unionist government elected with a strong majority.[14][16]

Remove ads

Relationship with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

Summarize

Perspective

From 1867 to 1949, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council served as the highest court of appeal in Canada, and its decisions on Canadian appeals were binding on all Canadian courts. After the creation of the Supreme Court of Canada, parties could still—if both consented—appeal directly from a provincial court of appeal to the Judicial Committee, bypassing the Supreme Court. This became common practice.[17] By 1900, the Privy Council had become dominant in Canadian jurisprudence, often deciding cases with "little or no restraint or respect" for the decisions of the Canadian courts from which the appeals originated.[18] By the early 20th century, it was regarded as a normal part of the Canadian legal system, no longer limited to exceptional cases, a point the Committee itself stressed when urging Canadian lawyers to bring forward only cases of significance or importance.[19]

In the early 1900s, public opinion began to turn against the Privy Council. Bushnell notes that national pride and imperial resentment grew in the aftermath of the Alaska Boundary Dispute and the Boer War.[13] Criticism of the Privy Council began to appear in the press, prompting the legal profession to respond in its own journals.[13] Liberal-linked media advocated restricting the appeal, while Conservative-linked media argued for its retention.[20] Former Supreme Court justice Wallace Nesbitt published an article broadly supporting the council with romantic language describing the broad jurisdiction of the Court.[13] When the Privy Council overturned the Street Railway Case (1907), Toronto newspapers criticized it as being out of touch with Canadian values.[21]

In 1895, the Parliament of the United Kingdom amended the Judicial Committee's constituting documents to allow the Queen to summon a limited number of colonial justices.[22] In 1909, Chief Justice Fitzpatrick was appointed to the Imperial Privy Council, giving him the right to sit on the Judicial Committee alongside former Chief Justice Henri-Elzéar Taschereau. His appointment was delayed because the maximum number of appointments from Canada was two, and former Chief Justice of Samuel Henry Strong refused to resign despite no longer attending sessions.[23]

Between 1903 and 1913, 14.5 per cent of all Supreme Court decisions were appealed to the Privy Council, a much higher rate than under the Strong Court, which had only 5.1 per cent appealed.[24]

- The Street Railway Case (1907): on construing a contract and territorial limits. Lord Collins overturned the decision of the Supreme Court.[ps 2]

- The Annuities Case (1910): on whether the federal or provincial government is liable for Treaty 3 annuity payments. Canada claimed Ontario was required to make Treaty annuity payments. Lord Loreburn upheld the Supreme Court's decision, holding that the Treaty was between the federal Crown and Ojibway, and that the that the federal and provincial governments "were separately invested by the Crown with its rights and responsibilities as treaty maker and as owner respectively."[ps 3]

Remove ads

Rulings of the Court

Summarize

Perspective

The Fitzpatrick Court continued the growth in the number of appeals heard by the Court from the Taschereau Court era, and a growing efficiency of the Court to handle those appeals.[25]

- Iredale v Loudon (1908): on adverse possession. A 3–2 majority of the Court held that Iredale acquired title to a second floor room of a building, but did not acquire a proprietary right to the supports in the building, rejecting an injunction preventing the demolition of the building.[26][ps 4]

- Stuart v Bank of Montreal (1909): on stare decisis. A 4–1 majority of the Court adopted a formalistic approach to stare decisis, choosing to be bound by previous decisions despite the grounds available to distinguish the decision.[27][ps 5]

- In re References by Governor-General in Council (1910): on the validity of the reference question authority. A 5–1 majority upheld the validity of the reference question authority, with all justices providing separate reasons. The only common element was that reference opinions were advisory in nature and not binding on any courts.[28][ps 6] The decision was upheld by the Privy Council.[ps 7]

- In Re Marriage Laws (1912): on solemnization of marriage and the Ne Temere Decree. A 4–1 majority of the Court held that the provincial power to solemnize marriage under section 92(12) of the Constitution Act, 1867, was broad in scope, absolute, and meant to cover the entire contract.[ps 8] The composition of the Court at the time was evenly split, 3–3 between Protestants and Roman Catholics.[29]

- In Re Gray (1918): on the constitutionality of Henry VIII Clauses. Gray's exemption to conscription was cancelled by order-in-council, he challenged his detention on the ground Parliament's delegation of legislative powers to Cabinet was ultra vires. The Court held a special session to hear the case. The 4–2 majority held that the legislature can delegate its legislative powers.[30][ps 9]

Remove ads

Administration of the Court

Summarize

Perspective

The Court operated with a panel of six judges, with a quorum of four judges, meaning that if there was an equal division (3—3), the appeal would be dismissed.[31][32] It was also common for each justice to write their own individual reasons for judgement rather than issuing joint judgments.[33] This practice, prevalent in the 1880s, continued into the 20th century.[34][35] Combined with the frequent dismissal of appeals due to tied votes, made it difficult to establish clear legal precedents or to discern whether a coordinated judicial approach existed. As a result, the Court primarily resolved disputes by applying existing legal principles, rather than by setting new legal standards.[36] Under the Supreme Court Act, the Court held three sessions per year.[37]

Several attempts in the 1890s and 1900s to permit federal or provincial court justices to sit as ad hoc members of the Court failed.[32] In 1910, Justice Anglin submitted a draft bill to the government to permit ad hoc members without notifying other justices, which was ignored by the government.[38] In 1918, after the Court was forced to suspend a sitting due to unavailability of its members, the government passed a bill permitting the Chief Justice to appoint an ad hoc judge from the Exchequer Court or a provincial chief justice.[38][ps 10] In practice, the Court appointed ad hoc justices based on proximity, bringing the Chief Justice of the King's Bench of Ontario William Glenholme Falconbridge when Duff of British Columbia, or Fitzpatrick of Quebec were absent.[39][ps 11]

In its early years, the Court did not sit at a traditional shared bench. Instead, each of the six justices had individual desks. Historians Snell and Vaughan note that this setup coincided with a period in the 1880s marked by deep divisions within the Court and a lack of "consultation and cooperation" among the justices.[40] The 1890s saw the introduction of judicial conferences,[41] which increased in frequency and use under Chief Justice Fitzpatrick.[42] The Chief Justice was even known to consult Court staff members including his secretary and the Court Registrar on his draft decisions.[42]

Under Chief Justice Fitzpatrick, the Court made several changes to improve efficiency and administration for French language appeals. In 1907, to increase efficiency of the Court, the rules of the Court restricted the number of counsel that could be heard by each side of a case to two, and a maximum time of three hours for arguments.[25] In 1908, a French stenographer was appointed to the Court staff.[25]

The Court recognized the right of applicants from Quebec to use either English or French. While French-language materials were accepted, they were translated into English at the Court's expense.[43] The Supreme Court Act required the Court to publish its own decisions rather than relying on private law reporters, an innovation not found elsewhere in the British Empire. This self-publishing model was intended to ensure that decisions would quickly reach legal professionals and lower court judges.[44] Judgments published in the Supreme Court Reports were printed in the language in which they were delivered and were not translated.[43] Despite its promise, the Supreme Court Reports continued to face criticism for numerous shortcomings, including errors, inconsistent editing and citations, a lack of uniform style, poorly written headnotes, and delays from decision to date of publication.[45]

Growing political role of the Court

Snell and Vaughan note that close connections and political involvement between the justices and the government were common and encouraged at the time, and not seen as inappropriate.[46]

With some exceptions, Laurier's Supreme Court appointments were highly partisan.[29] In the early 20th century, the Court and its justices became involved in national politics through appointments to government bodies and an increasing use of reference questions.[29] As these references grew more political, they exposed the Court to attack from the Conservative opposition.[29]

Chief Justice Fitzpatrick took an extensive public role, which Snell and Vaughan describe as appearing "non-partisan."[47] He lobbied the government to appoint Judge Cannon of Quebec to the Court after Justice Robert Sedgewick death and had a personal debt of $5,000 (equivalent to $142,461 in 2023) to Prime Minister Laurier.[47] Fitzpatrick's political advice was not limited to the Liberal government, he also advised the Conservative Borden government on Senate appointments, legislation, and political advice on issues in Quebec.[47] Snell and Vaughan note that Fitzpatrick acted as Prime Minister Borden's personal agent to the Quebec Conservative Party.[47]

In 1911, Minister of Labour and future Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King used his office to interfere with the Court's hearing of a case affecting his grandfather's reputation.[25][ps 12] King and his cousin wrote directly to a justice, providing facts not on the record that later emerged in litigation.[25] Snell and Vaughan speculate that Justice Anglin's dissent, which supported King's position, may have influenced his appointment as Chief Justice in 1924.[48]

In 1917, a group of Irish Catholics including Chief Justice Fitzpatrick, Justice Anglin, Minister of Justice Charles Doherty, and politician Charles Murphy urged Prime Minister Robert Borden to pressure the United Kingdom to permit home rule for Ireland.[49]

Changes to the structure and jurisdiction of the Court

In the early 20th century, there were serious proposals to alter the Supreme Court's structure and jurisdiction. One, considered seriously by the government, would have divided the Court's work along geographic lines, creating separate courts for Eastern and Western Canada.[24] As Leader of the Opposition, Wilfrid Laurier had argued that provincial superior courts should interpret provincial laws, while the Supreme Court and federal courts should be confined to interpreting federal laws. In 1908, Ontario Attorney General James Joseph Foy introduced resolutions urging the federal government to restrict appeals to both the Supreme Court and the Privy Council, making provincial appellate courts the final authority except in constitutional matters.[50] These debates, present since the Court's creation in the 1870s, reflected a tension over whether the Court should serve as a unifying force in Canadian law or focus solely on federal jurisdiction.[24]

Improving inter-personal relationships of the Court

Snell and Vaughan note that the retirement of Chief Justice Samuel Henry Strong led to an improvement in the inter-personal relationships of the Court. Several of the Justices made efforts to create a cooperative atmosphere at the Court.[51] The Chief Justice Fitzpatrick's efforts were a main catalyst for this improvement, including securing a knighthood for the senior Puisne Justice Girouard.[42] When conflicts did arise, justices were cooperative and the issues did not linger.[42]

Other instances demonstrating the improved relationships on the Court include Justice Wallace Nesbitt held an informal dinner to welcome Lyman Duff after his resignation.[42]

Costs and salaries of the Court

The cost of operating the Supreme Court steadily increased—from $54,530 in 1880 (equivalent to $1,792,564 in 2023), to $60,840 in 1890 (equivalent to $2,208,249 in 2023), and $66,087 in 1900 (equivalent to $2,542,306 in 2023).[52] These rising costs regularly drew criticism from the opposition. Justice Minister and future Supreme Court Justice David Mills remarked that "maintaining [the Court] costs altogether too much for what it does."[52] In 1903, pensions became more generous for the lifetime of the justice, and in 1906, the salary of a justice was raised to $9,000 (equivalent to $288,433 in 2023), with an additional $1,000 for the Chief Justice.[53]

The Chief Justice received a $2,500 allowance to cover travel costs to England to sit as a member of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. In 1914, Chief Justice Fitzpatrick claimed the allowance despite not attending any sittings. The following year, the description of the allowance was amended to remove the travel requirement and instead apply generally to "expenses in connection with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council." In 1917, it was amended again to require attendance.[54] In 1918, John Wesley Edwards, and later William Folger Nickle, raised concerns in Parliament about Fitzpatrick's use of the allowance. Edwards accused him of "deliberately stealing from the treasury of the country." Fitzpatrick and Prime Minister Robert Borden responded that there was no legal issue and that Fitzpatrick had acted in good faith. When Edwards revived the issue the following year, Fitzpatrick, by then Lieutenant Governor of Quebec, returned the allowance.[55]

Expansion of duties of justices

In the late 1890s, Supreme Court justices increasingly accepted additional roles at the government's request, reflecting both the Court's growing stature and its deeper involvement in public affairs beyond the bench. These political and quasi-judicial roles reflected a gradual increase in respect for the Court,[22] but also reinforced the view that it was a political tool rather than an institution separate from government.[56]

In 1907, Chief Justice Fitzpatrick was appointed to the Pecuniary Claims Arbitration Commission of Great Britain and the United States, which handled disputes between Canada and the United States.[56] In 1909, he became a British member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a role he valued and made a considerable effort to be reappointed in 1913.[23] He later served on the International Claims Commission between the United States and France and as Canada's representative to the International Peace Commission in 1915.[56]

In 1916, Prime Minister Borden appointed Justice Duff to a two-man Royal Commission to investigate Minister Sam Hughes and munitions contracts. Snell and Vaughan describe this as an "obviously partisan" role that exposed the Court to political attack.[56] The following year, Duff was appointed sole central appeal judge for conscription exemptions under the Military Service Act.[56][ps 13] After the war, he ordered all records of the appeal bodies destroyed, noting that "papers of the local tribunals and appeal bodies in Quebec were full of hatred and bitterness and would have been a living menace to national unity." He then took a leave of absence due to "nervous exhaustion."[57]

Remove ads

Appraisal

Summarize

Perspective

Historian Ian Bushnell describes the Supreme Court from 1903 to 1929, covering the Taschereau, Fitzpatrick, Davies, and Anglin Courts, as "the sterile years."[58] During this period, disunity in decision-making reached new heights, making it difficult to discern overarching legal principles.[59] As a result, the Court's jurisprudence was of limited value. This made retaining appeals to the Privy Council attractive, since a single decision from London provided greater certainty in the law.[59]

Criticism focused on the politically motivated nature of many judicial appointments.[60] While some legal journals occasionally defended the Court against press criticism, Bushnell notes these defences were motivated more by a desire to uphold the credibility of the legal system as a whole, than to support the Court itself.[61] Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier appointed 10 justices and had the opportunity to shape the Court, but, there was no consistent approach to appointments during the era.[62] Appointments were a mix of merit, patronage, and government interests, rather than what was best for the long-term development of the Court.[63] The political nature of appointments, combined with the Court's use as a political tool, contributed to institutional decline during the Fitzpatrick era.[24]

In its written decisions, the Court's reasoning during this period was largely formulaic and conservative, likely because it continued to view itself as an intermediate appellate body to the Privy Council.[27] As a result, the Court made little contribution to developing the law, and issuing decisions that drew ridicule from the public and legal community.[26] For instance, in civil rights, the Court followed earlier precedent to uphold laws infringement of Chinese-Canadian civil liberties.[64][ps 14] Snell and Vaughan note that by rationalizing popular racial discrimination, the Court helped entrench legalized discrimination in Canada.[65] In employment law, the Court led by Justice Girouard, overturned appeal decisions holding employers liable in negligence for harm to employees in industrial accidents, and required substantial proof to bring such a claim.[66]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads