Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Economy of Iran

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Iran has a mixed, centrally planned economy with a large public sector.[24][needs update] It consists of hydrocarbon, agricultural and service sectors, in addition to manufacturing and financial services,[25] with over 40 industries traded on the Tehran Stock Exchange. With 10% of the world's proven oil reserves and 15% of its gas reserves, Iran is considered an "energy superpower".[26][27][28][29][30] Nevertheless since 2024, Iran has been suffering from an energy crisis.

This article needs to be updated. (April 2023) |

Since the 1979 Islamic revolution, Iran's economy has experienced slower economic growth, high inflation, and recurring crises. The 8-year Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), increased Corruption in Iran, and subsequent international sanctions severely disrupted development.[31] In recent years, Iran's economy has faced stagnant growth, inflation rates among the highest in the world, currency devaluation, rising poverty, water and power shortages, and low rankings in corruption and business climate indices. The brief war with Israel in June 2025 further exacerbated economic pressures, causing billions in damage and loss of revenues.[32] Despite possessing large oil and gas reserves, Iran's economy remains burdened by structural challenges and policy mismanagement, resulting in limited growth and a decline in living standards in the post-revolution era.[33]

A unique feature of Iran's economy is the reliance on large religious foundations called bonyads, whose combined budgets represent more than 30 percent of central government spending.[citation needed]

In 2007, the Iranian subsidy reform plan introduced price controls and subsidies particularly on food and energy.[34][35] Contraband, administrative controls, widespread corruption,[36][37] and other restrictive factors undermine private sector-led growth.[38] The government's 20-year vision involved market-based reforms reflected in a five-year development plan, 2016 to 2021, focusing on "a resilient economy" and "progress in science and technology".[39] Most of Iran's exports are oil and gas, accounting for a majority of government revenue in 2010.[40] In March 2022, the Iranian parliament under the then new president Ebrahim Raisi decided to eliminate a major subsidy for importing food, medicines and animal feed, valued at $15 billion in 2021.[41] Also in March 2022, 20 billion tons of basic goods exports from Russia including vegetable oil, wheat, barley and corn were agreed.[41]

Iran's educated population, high human development, constrained economy and insufficient foreign and domestic investment prompted an increasing number of Iranians to seek overseas employment, resulting in a significant "brain drain".[38][42][43][44] However, in 2015, Iran and the P5+1 reached a deal on the nuclear program which removed most international sanctions. Consequently, for a short period, the tourism industry significantly improved and the inflation of the country was decreased,[citation needed] though US withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 hindered the growth of the economy again and increased inflation.[citation needed]

GDP contracted in 2018 and 2019, but a modest rebound was expected in 2020.[45] Challenges include a COVID-19 outbreak starting in February 2020, US sanctions reimposed in mid-2018, increased unemployment due to the sanctions,[45] inflation,[39][45] food inflation,[46] a "chronically weak and undercapitalized" banking system,[45][47] an "anemic" private sector,[45] and corruption.[48] Iran's currency, the Iranian rial, has fallen,[49] and Iran has a relatively low rating in "Economic Freedom",[50][45] and "ease of doing business".[51] Recently, Iran faces severe economic challenges resulting from long conflict with Israel and the war that broke between the two states, which resulted in a destruction of investments of more than 3 trillion USD.[52]

Remove ads

History until 1979

Summarize

Perspective

In 546 BC, Croesus of Lydia was defeated and captured by the Persians, who then adopted gold as the main metal for their coins.[53][54] There are accounts in the biblical Book of Esther of dispatches being sent from Susa to provinces as far out as India and the Kingdom of Kush during the reign of Xerxes the Great (485–465 BC). By the time of Herodotus (c. 475 BC), the Royal Road of the Persian Empire ran some 2,857 km from the city of Susa on the Karun (250 km east of the Tigris) to the port of Smyrna (modern İzmir in Turkey) on the Aegean Sea.

Modern agriculture in Iran dates back to the 1850s when Amir Kabir undertook a number of changes to the traditional agricultural system. Such changes included importing modified seeds and signing collaboration contracts with other countries. Polyakov's Bank Esteqrazi was bought in 1898 by the Tsarist government of Russia, and later passed into the hands of the Iranian government by a contract in 1920.[55] The bank continued its activities under the name of Bank Iran until 1933 when incorporating the newly founded Keshavarzi Bank.[55][56]

The Imperial Bank of Persia was established in 1885, with offices in all major cities of Persia.[55] Reza Shah Pahlavi (r. 1925–41) improved the country's overall infrastructure, implemented educational reform, campaigned against foreign influence, reformed the legal system, and introduced modern industries. During this time, Iran experienced a period of social change, economic development, and relative political stability.[56]

Reza Shah Pahlavi, who abdicated in 1941, was succeeded by his son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (r. 1941–79). No fundamental change occurred in the economy of Iran during World War II and the years immediately following. Between 1954 and 1960 a rapid increase in oil revenues and sustained foreign aid led to greater investment and fast-paced economic growth, primarily in the government sector. Subsequently, inflation increased, the value of the national currency, the rial, depreciated, and a foreign-trade deficit developed. Economic policies implemented to combat these problems led to declines in the rates of nominal economic growth and per capita income by 1961.[56]

Remove ads

History since the 1979 Islamic revolution

Summarize

Perspective

Prior to 1979, Iran developed rapidly. Traditionally agricultural, by the 1970s, the country had undergone significant industrialization and modernization.[57][58] The pace slowed by 1978 as capital flight reached $30 to $40 billion 1980-US dollars just before the revolution.[59]

Following the nationalizations in 1979 and the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War, over 80% of the economy came under government control.[citation needed] The eight-year war with Iraq claimed at least 300,000 Iranian lives and injured more than 500,000. The cost of the war to Iran's economy was some $500 billion.[60]

After hostilities ceased in 1988, the government tried to develop the country's communication, transportation, manufacturing, health care, education and energy sectors, including its prospective nuclear power facilities, and began integrating its communication and transportation systems with those of neighboring states.[61]

The government's long-term objectives since the revolution were stated as economic independence, full employment, and a comfortable standard of living but Iran's population more than doubled between 1980 and 2000 and its median age declined.[62] Although many Iranians are farmers, agricultural production has consistently fallen since the 1960s. By the late 1990s, Iran imported much of its food. At that time, economic hardship in the countryside resulted in many people moving to cities.[59]

Due to its relative isolation from global financial markets, Iran was initially able to avoid recession in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis.[63] However, following expansion of international sanctions related to Iran's nuclear programme, the Iranian rial fell to a record low of 23,900 to the US dollar in September 2012.[64][65][66][67]

- The Provinces of Iran by their contribution to national GDP, 2014

- Historical GDP per capita development in Iran, 1820–2018

- Economic sectors, 2002

- Inflation rate, 1980–2010

- Market liquidity, 2012

- US dollar/Iranian rial exchange rate, 2003–2014 est.

- Debt service, 1980–2000

- Balance of payment, 2003–2007

- Oil production and consumption, 1977–2010

- Oil and gas production, 1970–2030 est.

Remove ads

Macroeconomic trends

Summarize

Perspective

Iran's national science budget in 2005 was about $900 million, roughly equivalent to the 1990 figure.[68] By early 2000, Iran allocated around 0.4% of its GDP to research and development, ranking the country behind the world average of 1.4%.[69] In 2009 the ratio of research to GDP was 0.87% against the government's medium-term target of 2.5%.[70] Iran ranked first in scientific growth in the world in 2011 and 17th in science production in 2012.[citation needed]

Iran has a broad and diversified industrial base.[71] According to The Economist, Iran ranked 39th in a list of industrialized nations, producing $23 billion of industrial products in 2008.[72] Between 2008 and 2009 Iran moved to 28th from 69th place in annual industrial production growth because of its relative isolation from the 2008 financial crisis.[73]

In the early 21st century, the service sector was Iran's largest, followed by industry (mining and manufacturing) and agriculture.

Growth

Iran's long-term economic growth since the 1979 Islamic Revolution has been far below its pre-revolution performance. According to Central Bank data, GDP grew on average only about 1.9% per year from 1979 to 2020, compared to 9.1% annually in 1960–1979 before the revolution.[74] The Iran–Iraq War (1980–88) caused a deep recession: during 1981–89 Iran's GDP grew only 0.9% annually on average, the lowest of any period, as war destruction and revolutionary upheaval crippled output.[74] In the early 1990s, after the war, Iran saw a rebound – President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani's administration (1989–1997) achieved about 5.5% average growth by rebuilding infrastructure and liberalizing parts of the economy.[74]

In 2008, Iran's GDP was estimated at $382.3 billion ($842 billion PPP), or $5,470 per capita ($12,800 PPP).[38]

In 2010, the nominal GDP was projected to double in the next five years.[75] Real GDP growth was expected to average 2.2% a year in 2012–16, insufficient to reduce the unemployment rate.[76] Furthermore, international sanctions have damaged the economy by reducing oil exports by half, before recovering in 2016.[77][78] The Iranian rial lost more than half of its value in 2012, directing Iran to import substitution industrialization and a resistive economy.[77][79] According to the International Monetary Fund, Iran is a "transition economy", i.e., changing from a planned to a market economy.[80]

In 2008, the United Nations classified Iran's economy as semi-developed.[81] In 2014, Iran ranked 83rd in the World Economic Forum's analysis of the global competitiveness of 144 countries.[82][83][84]

In 2008, according to Goldman Sachs, Iran has the potential to become one of the world's largest economies in the 21st century.[85][86] In 2014, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani stated that Iran has the potential to become one of the ten largest economies within the next 30 years.[87]

The lifting of sanctions in 2016 under the JCPOA nuclear deal spurred a one-time jump of 12.5% GDP growth in 2016, Iran's only double-digit growth in decades (mostly from restored oil exports).[88][89] But after the United States reimposed sanctions in 2018, Iran entered another downturn (GDP fell in 2018–2019). The 2011–2020 period is regarded as a "lost decade" for Iran's economy, with average growth near 0.5%, due to sanctions, capital flight, and low investment.[90][91]

After a modest recovery in 2020–2022, the IMF and World Bank estimated Iran's real GDP growth at around 2–5% in 2022–2024, partly due to higher oil prices and improved non-oil output.[92][93] However, for 2025 the outlook turned grim: after new U.S. sanctions and the mid-2025 conflict, the IMF projected near zero growth (0.3%) for 2025, revising down earlier forecasts.[94] Oil production and exports have been constrained by sanctions and the 2025 war damage; Iran's oil exports, which averaged ~1.4–1.7 million barrels/day in 2024, were expected to drop by several hundred thousand barrels in 2025 under sanctions.[94][95]

250

500

750

1,000

1,250

1,500

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

2000

2004

2008

2012

2015

- GDP, PPP, million (current international $)

- GDP per capita, PPP (current international $)

Reform plan

Expansion of public healthcare and international relations are the other main objectives of the fifth plan, an ambitious series of measures that include subsidy reform, banking recapitalization, currency, taxation, customs, construction, employment, nationwide goods and services distribution, social justice and productivity.[97] The intent is to make the country self-sufficient by 2015 and replace the payment of $100 billion in subsidies annually with targeted social assistance.[98][99][100][101] These reforms target Iran's major sources of inefficiency and price distortion and are likely to lead to major restructuring of almost all economic sectors.[99]

By removing energy subsidies, Iran intends to make its industries more efficient and competitive.[102] By 2016, one third of Iran's economic growth is expected to originate from productivity improvement. Energy subsidies left the economy as one of the world's least energy-efficient, with energy intensity three times the global average and 2.5 times higher than the Middle Eastern average.[103] Notwithstanding its own issues, the banking sector is seen as a potential hedge against the removal of subsidies, as the plan is not expected to directly impact banks.[104]

Remove ads

National planning

Summarize

Perspective

Iran's budget is established by the Management and Planning Organization of Iran and proposed by the government to the parliament before the year's end. Following approval of the budget by Majlis, the central bank presents a detailed monetary and credit policy to the Money and Credit Council (MCC) for approval. Thereafter, major elements of these policies are incorporated into the five-year economic development plan.[56] The plan is part of "Vision 2025", a strategy for long-term sustainable growth.[105]

- Sixth development plan (2016–2021)

The sixth five-year development plan for the 2016–2021 period places emphasis on "guidelines" rather than "hard targets".[134] It defines only three priorities:

Remove ads

Fiscal policy

Summarize

Perspective

Since the 1979 revolution, government spending has averaged 59% on social policies, 17% on economic matters, 15% on national defense, and 13% on general affairs.[56] Payments averaged 39% on education, health and social security, 20% on other social programs, 3% on agriculture, 16% on water, power and gas, 5% on manufacturing and mining, 12% on roads and transportation and 5% on other economic affairs.[56] Iran's investment reached 27.7% of GDP in 2009.[38] Between 2002 and 2006, inflation fluctuated around 14%.[136]

In 2008, around 55% of government revenue came from oil and natural gas revenue, with 31% from taxes and fees.[137][138] There are virtually millions of people who do not pay taxes in Iran and hence operate outside the formal economy.[38] The budget for year 2012 was $462 billion, 9% less than 2011.[139] The budget is based on an oil price of $85 per barrel. The value of the US dollar is estimated at IRR 12,260 for the same period.[139]

According to the head of the Department of Statistics of Iran, if the rules of budgeting were observed the government could save at least 30 to 35% on its expenses.[140] The central bank's interest rate is 21%, and the inflation rate has climbed to 22% in 2012, 10% higher than in 2011.[141] There is little alignment between fiscal and monetary policy. According to the Central Bank of Iran, the gap between the rich and the poor narrowed because of monthly subsidies but the trend could reverse if high inflation persists.[142]

Defense related burden

According to official data, as of 2023 Iran spends 10.3 billion USD or 2.1% of its GDP on national defense. This percentage is similar to that in other countries such as UK, France and Finland.[143]

In 2025, the Iranian budget bill granted 51% of the total oil and gas export revenues, estimated at 12 billion euros, to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Law Enforcement Command (LEF).[144][145]

Iran also finances Hezbollah, the Yemeni Houthis, Iraqi militia, and Hamas. The average annual budget reserved for the funding of Iran's proxies is estimated at US$1.6 billion.[146] According to Syrian opposition sources, starting from the beginning of 2011, Iran allocated a total of US$50 billion to maintain the Assad regime in Syria. However, this investment proved to be a failure following the eventual collapse of the regime.[147][148]

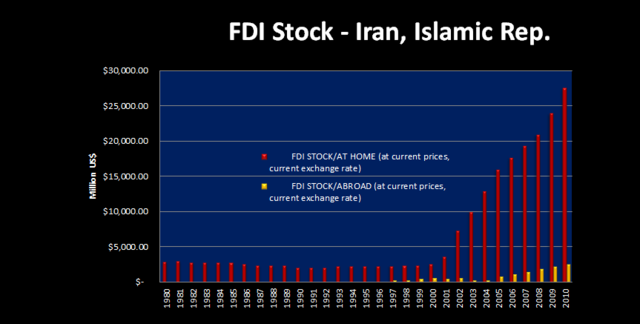

The most costly of Iran's defense expenditures is its nuclear program. The estimated total cost of Iran's nuclear program until 2025 approaches US$500 billion.[149][150] As a result of its nuclear program Iran is subject to international sanctions, causing a long-term economic stagnation which cost Iran an additional US$1.2 trillion over 12 years.[151][152] Furthermore, the sanctions led to a significant decline in foreign direct investments (FDI), with Iran experiencing a reduction of approximately 80% in FDI between 2011 and 2021.[153]

Remove ads

Corruption and governance indices

Summarize

Perspective

Corruption

Iran consistently ranks poorly on international corruption and governance indices. In Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Iran scores very low – in the 2023 CPI report, Iran scored 23/100, ranking 151st out of 180 countries (among the worst 20% globally for perceived public-sector corruption).[154] This was a slight decline from the previous year (score 24). Issues include widespread bureaucratic corruption, bribery, embezzlement, and the influence of powerful organizations that operate outside formal oversight (like parastatal religious foundations and the Revolutionary Guard's economic wing). Corruption has been cited as a major obstacle to investment and equitable growth in Iran.[155] Iranian leaders, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, have at times called for "jihad against corruption", and some high-profile arrests/trials have occurred (e.g. banking fraud scandals). However, critics argue that many corrupt actors enjoy impunity, especially if politically connected, and that anti-corruption efforts are often politicized or selective.[156][157]

Ease of doing business

The business climate in Iran is widely seen as difficult. In the World Bank's now-discontinued Ease of Doing Business Index, Iran was ranked around 127th out of 190 countries in the last published report (Doing Business 2020), reflecting a generally poor environment for starting and running private businesses.[158] Cumbersome regulations, lengthy permit processes, weak contract enforcement, and barriers to trade and finance all contributed to this low ranking. Although Iran made some reforms (e.g. simplifying business registration and improving access to credit information), it lagged behind regional peers. International sanctions added another layer of difficulty, as Iranian firms were cut off from global banking and faced restrictions on imports/exports.[158]

Iran is rated as "Repressed" economically in the Heritage Foundation's Index of Economic Freedom. In the 2025 Heritage index, Iran's score was 42.5 (out of 100), ranking it 169th in the world (near the bottom, among countries with least economic freedom).[159] This reflects extensive state intervention, weak property rights, and lack of investment freedom. Large sectors of Iran's economy are dominated by the government or semi-state entities (including the bonyads and IRGC-affiliated companies), leading to oligopolies and limited competition. The judiciary's lack of independence and rule-of-law issues also deter investors.[159]

Governance indicators

Governance indicators by the World Bank also rate Iran poorly on control of corruption, regulatory quality, and rule of law.[160][161] These problems have tangible impacts: for example, cumbersome customs procedures and the prevalence of informal payments increase costs for businesses; unclear property rights or contract enforcement discourages entrepreneurship. International companies have largely shied away from investing in Iran (aside from some Chinese, Russian, and regional firms) due not only to sanctions but also concerns about transparency and predictability.[162] Iran's government acknowledges the need to improve its business environment – the Rouhani administration (2013–2021) made it a goal to climb rankings – but progress has been limited, especially as U.S. sanctions returned.[162]

Remove ads

Inflation

Summarize

Perspective

Inflation in Iran has been persistently high since the revolution, eroding living standards. During 1960–1978, Iran's inflation was usually in single digits, but after 1979 it surged into double digits almost every year. From 1979 to 2024, consumer prices increased astronomically – an item that cost 100 rials in 1960 costs over 2 million rials by 2025.[163] The average inflation rate since 1979 has been about 17–18% per year, compared to under 10% before 1979.[163][93] Periodic bouts of very high inflation occurred: in the 1980s during the war and money-printing, inflation topped 20–30%. In the 1990s, it spiked above 50% (in 1995). Tightening measures brought inflation down to ~10% by the early 2000s, but it accelerated again later. International sanctions on Iran's oil and banking (especially 2012 and 2018 onward) led to currency devaluation and shortages, driving inflation to 30–50% annually in 2018–2023.[164] By 2023–2024, Iran's annual inflation was roughly 40%, particularly elevated for food prices, which led to steep declines in real incomes.[165] In 2025, amid renewed sanctions and war disruption, the IMF raised Iran's projected inflation to over 43%, placing Iran as the 4th-highest inflation country globally (after Venezuela, Sudan, Zimbabwe).[94][166] The latest data shows that the annual inflation rate reached 38.7% in May 2025.[167] Due to the high inflation and the devaluation of the Iranian real (90% since 2018)[167] have brought the Iran's parliament to approve a bill in committee that paves the way to remove four zeros from the national currency, the rial, in an effort to tackle long-term inflation. However, experts say that while cutting zeros from the currency may have some benefits, it does not offer a clear solution to Iran’s deeper economic problems.[167]

In August Iran effectively raised taxation by introducing a new law making inflation partly taxable framing it as a tool against hoarding in a country where inflation often exceeds 40 percent.[168]

Remove ads

The current account

Summarize

Perspective

Iran had an estimated $110 billion in foreign reserves in 2011[169] and balances its external payments by pricing oil at approximately $75 per barrel.[170] As of 2013, only $30 to $50 billion of those reserves are accessible because of current sanctions.[171] Iranian media has questioned the reason behind Iran's government non-repatriation of its foreign reserves before the imposition of the latest round of sanctions and its failure to convert into gold. As a consequence, the Iranian rial lost more than 40% of its value between December 2011 and April 2012.[142]

Iran's external and fiscal accounts reflect falling oil prices in FY 2012, but remain in surplus. The current account was expected to reach a surplus of 2.1% of GDP in FY 2012, and the net fiscal balance (after payments to Iran's National Development Fund) will register a surplus of 0.3% of GDP.[76] In 2013 the external debts stood at $7.2 billion down from $17.3 billion in 2012.[172] Overall fiscal deficit is expected to deteriorate to 2.7% of GDP in FY 2016 from 1.7% in 2015.[173]

Money in circulation reached $700 billion in March 2020 (based on the 2017 pre-devaluation exchange rate), thus furthering the decline of the Iranian rial and rise in inflation.[174][175]

The Iranian Rial

The Iranian rial has continually lost value, especially since the 2010s. The currency was roughly 70 rials per US dollar before 1979; after the revolution and war, it fell to ~1,700 rials/USD by 1990s, and kept sliding.[176] Following the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal (2018) and sanctions, the rial's decline accelerated: the free-market exchange rate crossed 300,000 rials/USD in 2020, then 600,000 by late 2022, and hit 1,000,000 rials per USD in early 2025 – a psychological milestone of 1 million.[176][177] Authorities periodically attempted currency reforms, e.g., banning exchange shops, unifying rates, or proposing to cut four zeros from the currency, but the underlying pressures of limited foreign exchange and excess money supply have kept the rial weak.[178] By 2025, Iran's currency and inflation problems were severe enough that even basic goods saw rapid price rises, sparking protests over living costs.[179][180] Subsidy reforms (such as cutting the subsidized currency for imports in 2022) also led to jumps in prices of staples like bread and medicine.[181][182]

Remove ads

The stock market

Summarize

Perspective

Iran's stock market, the Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE), has experienced boom-and-bust cycles in recent years, often moving opposite to the real economy.[183] During recessions and currency devaluation, many Iranians invested in stocks as a hedge against inflation, fueling speculative rallies.[184] In 2019–2020, amid U.S. "maximum pressure" sanctions and a recession, the TSE index surged by over 500% within a year.[185] The index hit record highs (over 2 million points in Aug 2020), propelled by high liquidity and public campaigns by authorities for people to buy stocks. Analysts warned of a bubble, given poor economic fundamentals (GDP was shrinking and COVID-19 ravaged the economy).[186] By late 2020 and into 2021, the bubble burst – the market crashed over 30% from its peak by early 2021, wiping out many small investors' savings. Allegations emerged that government insiders had benefited from selling at highs, causing public mistrust.[187][188]

After a period of stagnation, the stock market rallied again in 2023, with the main TEDPIX index reaching about 3.2 million points by early 2025.[189] However, trading volumes were often driven by inflation hedge motives rather than corporate earnings. In mid-June 2025, the exchange was shut down for 9 days during the war with Israel, and when it reopened after the ceasefire, the market plunged sharply. Within the first three days post-war, the TSE's benchmark index fell by over 200,000 points (≈7%) to around 2.79 million, despite daily trading limits that normally slow declines.[189] Panicked investors placed massive sell orders, on the first day back, sell orders outweighed buy orders by a 220:1 ratio (31.9 trillion tomans sell vs 0.145 trillion buy), indicating widespread flight from equities.[189] The post-war drop highlighted fragile confidence: even before the conflict, many retail investors doubted the rally's sustainability and kept funds out of the market.[189] The government intervened by limiting daily price moves to 3% and has at times injected liquidity via state funds to stabilize stocks. Yet, structural issues, such as lack of market depth, high inflation, and political risks, continue to make Iran's stock market volatile. Following the war, analysts argued that without genuine government support (e.g. large capital injections like those used to stabilize the currency), the market downturn could deepen, as the war's aftermath and ongoing sanctions deter both local and foreign investors.[189]

In 2024, Iran passed a law to make a two-day weekend. Saturday was added to Friday weekends and Thursdays were removed. The work week was reduced from 44 hours to 40/42 hours.[190][191]

Remove ads

Challenges

Summarize

Perspective

The GDP of Iran contracted in FY 2018 and FY 2019 and modest rebound is expected in 2020/2021 according to an April 2020 World Economic Outlook by the IMF.[45] Challenges to the economy include the COVID-19 outbreak starting in February 2020, which on top of US sanctions reimposed in mid-2018 and other factors, led a fall in oil production and are projected to lead to a slow recovery in oil exports.[39] Labor-force participation has risen[45] but unemployment is above 10% as of 2020 and projected to rise in 2021 and 2022.[45]

Inflation reached 41.1% in 2019, and is expected to continue "in the coming years" according to the World Bank,[39] but decline into the 34-33% range.[45] In July 2022, the average inflation rate rose 40.5% while the inflation rate for food and beverages alone rose 87%.[192][193] Iran's banking system is "chronically weak and undercapitalised" according to Nordea Bank Abp,[45] holding billions of dollars of non-performing loans,[47] and the private sector remains "anemic".[45]

The unofficial Iranian rial to US dollar exchange rate, which had plateaued at 40,000 to one in 2017, has fallen 120,000 to one as of November 2019.[49] Iran's economy has a relatively low rating in the Heritage Foundation's "Index of Economic Freedom" (164 out of 180);[50][45] and ease of doing business ranking (127 among 190) according to the World Bank.[51] Critics have complained that privatization has led not to state owned businesses being taken over by "skilled businesspeople" but by the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps "and its associates".[194]

In 2020, an Iranian businessperson complained to a foreign journalist (Dexter Filkins) that the uncertainty of "chronic shortages of material and unruly inspectors pushing for bribes" made operating his business very difficult -- "Plan for the next quarter? I can't plan for tomorrow morning."[194]

In 2021, according to the NIOC, daily consumption of gasoline in Iran has surpassed 85 million liters, i.e., 10 times more than Turkey with almost the same population.[195]

Remove ads

Ownership

Summarize

Perspective

- Upper class (4.30%)

- Middle-class (32.0%)

- Working class (15.0%)

- Lower class/relative poverty (42.0%)

- Lower class/absolute poverty (6.70%)

Following the hostilities with Iraq, the Government declared its intention to privatize most industries and to liberalize and decentralize the economy.[199] Sale of state-owned companies proceeded slowly, mainly due to opposition by a nationalist majority in the parliament. In 2006, most industries, some 70% of the economy, remained state-owned.[38] The majority of heavy industries including steel, petrochemicals, copper, automobiles, and machine tools remained in the public sector, with most light industry privately owned.[38]

Article 44 of the Iranian Constitution declares that the country's economy should consist of state, cooperative, and private based sectors. The state sector includes all large-scale industries, foreign trade, major minerals, banking, insurance, power generation, dams and large-scale irrigation networks, radio and television, post, telegraph and telephone services, aviation, shipping, roads, railroads and the like. These are publicly owned and administered by the State. Cooperative companies and enterprises concerned with production and distribution in urban and rural areas form the basis of the cooperative sector and operated in accordance with Shariah law. As of 2012, 5,923 consumer cooperatives, employed 128,396.[200] Consumer cooperatives have over six million members.[200] Private sector operate in construction, agriculture, animal husbandry, industry, trade, and services that supplement the economic activities of the state and cooperative sectors.[201]

Since Article 44 has never been strictly enforced, the private sector has played a much larger role than that outlined in the constitution.[202] In recent years, the role of this sector has increased. A 2004 constitutional amendment allows 80% of state assets to be privatized. Forty percent of such sales are to be conducted through the "Justice Shares" scheme and the rest through the Tehran Stock Exchange. The government would retain the remaining 20%.[203][204]

In 2005, government assets were estimated at $120 billion. Some $63 billion of such assets were privatized from 2005 to 2010, reducing the government's direct share of GDP from 80% to 40%.[citation needed] Many companies in Iran remain uncompetitive because of mismanagement over the years, thus making privatization less attractive for potential investors.[205] According to then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, 60% of Iran's wealth is controlled by just 300 people.[206]

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are thought to control about one third of Iran's economy through subsidiaries and trusts.[207][208][209] 2007 estimates by the Los Angeles Times suggest the IRGC has ties to over one hundred companies and annual revenue in excess of $12 billion, particularly in construction.[210] The Ministry of Petroleum awarded the IRGC billions of dollars in no-bid contracts as well as major infrastructure projects.[211]

Tasked with border control, the IRGC maintains a monopoly on smuggling, costing Iranian companies billions of dollars each year.[207] Smuggling is encouraged in part by the generous subsidization of domestic goods, including fuel. The IRGC also runs the telecommunication company, laser eye-surgery clinics, makes cars, builds bridges and roads and develops oil and gas fields.[212]

Religious foundations

Welfare programs for the needy are managed by more than 30 public agencies alongside semi-state organizations known as bonyads, together with several private non-governmental organizations. Bonyads are a consortium of over 120 tax-exempt organizations that receive subsidies and religious donations. They answer directly to the Supreme Leader of Iran and control over 20% of GDP.[207][213] Operating everything from vast soybean and cotton farms to hotels, soft drink, automobile manufacturing, and shipping lines, they are seen as overstaffed, corrupt and generally unprofitable.[214]

Bonyad companies compete with Iran's unprotected private sector, whose firms complain of the difficulty of competing with the subsidized bonyads.[214] Bonyads are not subject to audit or Iran's accounting laws.[215] Setad is a multi-sector business organization, with holdings of 37 companies, and an estimated value of $95 billion. It is under the control of the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, and created from thousands of properties confiscated from Iranians.[216]

Remove ads

Labor force

Summarize

Perspective

After the revolution, the government established a national education system that improved adult literacy rates. In 2008, 85% of the adult population was literate, well ahead of the regional average of 62%.[218][219] The Human Development Index was 0.749 in 2013, placing Iran in the "high human development" bracket.[44]

In 2008, annual economic growth of above 5% was necessary to absorb the 750,000 new labor force entrants each year.[220] In 2020, agriculture was 10% of GDP and employed 16% of the labor force.[6] In 2017, the industrial sector, which includes mining, manufacturing, and construction, was 35% of GDP and employed 35% of the labor force.[6] In 2009, mineral products, notably petroleum, accounted for 80% of Iran's export revenues, even though mining employs less than 1% of the labor force.[70]

In 2004, the service sector ranked as the largest contributor to GDP, at 48% of the economy, and employed 44% of workers.[38] Women made up 33% of the labor force in 2005.[221] Youth unemployment, aged 15–24, was 29.1% in 2012, resulting in significant brain drain.[38][222] In 2016, according to the government, some 40% of the workforce in the public sector are either in excess or incompetent.[223]

Labor force and the public sector

The Islamic Republic of Iran employs around 8 million individuals, of whom roughly 3 million hold formal positions within the three branches of government, the armed forces, and leadership institutions. These roles encompass bureaucratic staff, civil servants, and uniformed military personnel.[224]

Beyond the formal government structure, approximately 2.3 million individuals are employed in quasi-governmental organizations, including state-owned enterprises, national banks, municipalities, and the Islamic Azad University. Additionally, about 2.5 million pensioners receive state stipends, often distributed through the Relief Committee, a government-controlled charitable organization. As a result, nearly one in ten Iranian citizens maintain a regular financial connection to the state.[224]

Unemployment

Unemployment in Iran has remained at high single digits officially, but underemployment and joblessness among youth are significant concerns. However, this headline figure masks labor force dropout: over 38 million working-age Iranians (especially women and youth) are economically inactive, and only 25 million were employed, indicating a very low labor participation rate (around 41%).[225][226] Youth unemployment is much higher: for ages 18–35 it was around 15%, and for 15–24 year-olds about 20% in 2024–25 (with young women's jobless rate even higher, near 35%).[227]

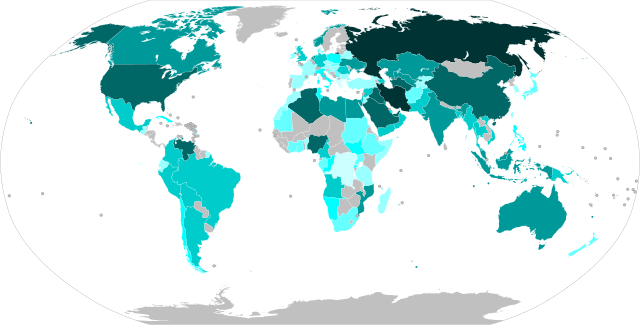

Personal income

Higher GNI per capita compared to Iran

Lower GNI per capita compared to Iran

Iran is classed as a middle income country and has made significant progress in provision of health and education services in the period covered by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In 2010, Iran's average monthly income was about $500. The GNI per capita in 2012 was $13,000, by PPP.[38][228][229][230] A minimum national wage applies to each sector of activity as defined by the Supreme Labor Council. In 2009 this was about $263 per month ($3,156 per year).[231]

In 2001, approximately 20% of household consumption was spent on food, 32% on fuel, 12% on health care and 8% on education.[232] In 2015, Iranians had little personal debt.[233] In 2007, seventy percent of Iranians owned their homes.[234]

In 2018–2019, the median household income of Iran was 434,905,000 rials (a bit above $3,300), an 18.6% rise from 2017 to 2018, when median household income was about 366,700,000 rials.[citation needed] Adjusted for purchasing power parity, Iran's 2017–2018 median income was equivalent to about $28,647 (2017 conversion factor, private consumption, LCU).[235]

As the average Iranian household size is 3.5, this puts median personal income at around $8,185.[236] While Iran rates relatively well on income, median wealth is very low for its income level, on par with Vietnam or Djibouti, indicating a high level of spending. According to SCI, median household spending in 2018 was 393,227,000 rials, or 90.5% of the median household income of 434,905,000 rials.[citation needed]

After the Revolution, the composition of the middle class in Iran did not change significantly, but its size doubled from about 15% of the population in 1979 to more than 32% in 2000.[237] In 2008, the official poverty line in Tehran for 2008 was $9,612. The national average poverty line was $4,932.[238] In 2010, Iran's Department of Statistics announced that 10 million Iranians live under the absolute poverty line and 30 million live under the relative poverty line.[239]

Salaries and wages in Iran have not kept up with inflation, causing a steep decline in real purchasing power. The government sets a national minimum wage annually through the Supreme Labor Council.[240] In March 2024, the minimum monthly wage was raised by 35% to 11,107,000 rials (about \$185 at the time, including certain benefits).[241] However, due to rapid rial depreciation, by late 2024 that amount was worth only ~$137, while the cost of living spiked causing a real decrease of wages.[242] Labor organizations note the minimum wage that once covered roughly half of a family's basic expenses now covers only one-quarter or less of essential costs.[241]

Income inequality

According the inequality dataset of the world bank, in 2002 the Gini index in Iran was 34.8, a level that is considered to be quite modest. However, closer data analysis reveals significant wealth concentration, with the top 10% of earners holding 52.7% of the national income - a larger share than in the United States or European countries.[243]

Iran's Gini coefficient fell from ~0.50 in the late 1970s to ~0.40 by the mid-1980s. In the 2000s, inequality fluctuated around a Gini index of 0.38–0.40. In the late 2010s and 2020s, some official data suggested a slight decline in the Gini (possibly due to overall economic contraction hitting higher incomes). The World Bank estimated Iran's Gini index at around 36.0 in 2019, improving to 34.8 in 2022 (on a 0–100 scale where higher is more unequal).[244]

Economic disparity is also evident within the public sector. Many Iranian state employees face significant financial hardship, with salaries as low as $200 per month, however, some Majlis representatives receive monthly salaries ranging from 200 to 250 million tomans (or more than $59,172 according to the exchange rate of January 2024).[245] Additionally, they receive extra bonuses during religious holidays and on "Parliament Day" and "Employee Day," along with perquisites like Nowruz and Yalda Night snacks.[246]

Inequality is also evident in access to essential services such as water supply. In Tehran impoverished districts struggle with inadequate water provision and hazardous water quality, while affluent areas, housing many of the nation's economic elite, including high-ranking government and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) officials, are largely unaffected by these shortages.[247]

The government has a sizable social transfer system (subsidies for fuel, bread, cash handouts introduced in 2010, etc.) which has helped limit extreme inequality.[248][249] However, wealth inequality is believed to be more pronounced – a small subset connected to power and business conglomerates (like religious foundations and the Revolutionary Guard's businesses) control significant assets, while many Iranians struggle. Notably, inequalities between urban and rural areas and between provinces persist.[250][251][252]

Poverty

Poverty levels in Iran have risen in recent years amid sanctions and inflation, after some improvements in the 2000s. The Research Center of Iran's Parliament reported that poverty reached 30.1% of the population in 2023, up from about 26% in 2018, meaning around 25–27 million people unable to meet basic needs.[253] Over 5 years, the poverty rate hovered around 30%, indicating persistent hardship. The World Bank estimated that in 2018, only 0.5% of Iranians lived on under $1.90/day (extreme poverty), but by 2021 the share living under the upper-middle-income country poverty line (~$6.85/day) had increased sharply due to inflation.[90] By March 2022, Iranian media reported over 32 million people (around 38% of the population) were below the poverty line when considering the ability to afford essential food and housing, as inflation in food prices outpaced incomes.[254]

Malnutrition in Iran has been reported as a growing social and economic issue amid the country’s ongoing economic crisis. In August 2025, the Iranian newspaper Shargh, citing surveys conducted by NGOs and volunteer groups, highlighted severe deficiencies in food access and nutrition, particularly protein intake, across the population.[255] The study revealed that only 1.7% of households reported daily protein consumption. About 27% of households reported no protein intake at all. Among households with temporary employment, over 93% consumed protein less than once a week or not at all. In unemployed households, this figure rose to 95%.[255]

Social security

Although Iran does not offer universal social protection, in 1996, the Iranian Center for Statistics estimated that more than 73% of the Iranian population was covered by social security.[256] Membership of the social security system for all employees is compulsory.[257]

Social security ensures employee protection against unemployment, disease, old age and occupational accidents.[258] In 2003, the government began to consolidate its welfare organizations to eliminate redundancy and inefficiency. In 2003 the minimum standard pension was 50% of the worker's earnings but no less than the minimum wage.[258] Iran spent 22.5% of its 2003 national budget on social welfare programs of which more than 50% covered pension costs.[259] Out of the 15,000 homeless in Iran in 2015, 5,000 were women.[260]

Employees between the age of 18 and 65 years are covered by the social security system with financing shared between the employee (7% of salary), the employer (20–23%) and the state, which in turn supplements the employer contribution up to 3%.[261] Social security applies to self-employed workers, who voluntarily contribute between 12% and 18% of income depending on the protection sought.[258] Civil servants, the regular military, law enforcement agencies, and IRGC have their own pension systems.[262]

Trade unions

Although Iranian workers have a theoretical right to form labor unions, there is no union system in the country. Ostensible worker representation is provided by the Workers' House, a state-sponsored institution that attempts to challenge some state policies.[263] Guild unions operate locally in most areas, but are limited largely to issuing credentials and licenses. The right to strike is generally not respected by the state. Since 1979 strikes have often been met by police action.[264]

A comprehensive law covers labor relations, including hiring of foreign workers. This provides a broad and inclusive definition of the individuals it covers, recognizing written, oral, temporary and indefinite employment contracts. Considered employee-friendly, the labor law makes it difficult to lay off staff. Employing personnel on consecutive six-month contracts (to avoid paying benefits) is illegal, as is dismissing staff without proof of a serious offense. Labor disputes are settled by a special labor council, which usually rules in favor of the employee.[257]

Sectors

Summarize

Perspective

Agriculture and foodstuffs

Agriculture contributes 9.5% to the gross domestic product and employs 17% of the labor force.[45] About 9% of Iran's land is arable,[265] with the main food-producing areas located in the Caspian region and in northwestern valleys. Some northern and western areas support rain-fed agriculture, while others require irrigation.[266] Primitive farming methods, overworked and under-fertilized soil, poor seed and water scarcity are the principal obstacles to increased production. About one third of total cultivated land is irrigated. Construction of multipurpose dams and reservoirs along rivers in the Zagros and Alborz mountains have increased the amount of water available for irrigation. Agricultural production is increasing as a result of modernization, mechanization, improvements to crops and livestock as well as land redistribution programs.[267]

Wheat, the most important crop, is grown mainly in the west and northwest. Rice is the major crop in the Caspian region. Other crops include barley, corn, cotton, sugar beets, tea, hemp, tobacco, fruits, potatoes, legumes (beans and lentils), vegetables, fodder plants (alfalfa and clover), almonds, walnuts and spices including cumin and sumac. Iran is the world's largest producer of saffron, pistachios, honey, berberis and berries and the second largest date producer.[268] Meat and dairy products include lamb, goat meat, beef, poultry, milk, eggs, butter, and cheese.

Non-food products include wool, leather, and silk. Forestry products from the northern slopes of the Alborz Mountains are economically important. Tree-cutting is strictly controlled by the government, which also runs a reforestation program. Rivers drain into the Caspian Sea and are fished for salmon, carp, trout, pike, and sturgeon that produce caviar, of which Iran is the largest producer.[267][269]

Since the 1979 revolution, commercial farming has replaced subsistence farming as the dominant mode of agricultural production. By 1997, the gross value reached $25 billion.[70] Iran is 90% self-sufficient in essential agricultural products, although limited rice production leads to substantial imports. In 2007 Iran reached self-sufficiency in wheat production and for the first time became a net wheat exporter.[270] By 2003, a quarter of Iran's non-oil exports were of agricultural products,[271] including fresh and dried fruits, nuts, animal hides, processed foods, and spices.[70] Iran exported $736 million worth of foodstuffs in 2007 and $1 billion (~600,000 tonnes) in 2010.[272] A total of 12,198 entities are engaged in the Iranian food industry, or 12% of all entities in the industry sector. The sector also employs approximately 328,000 people or 16.1% of the entire industry sector's workforce.[273]

Manufacturing

Large-scale factory manufacturing began in the 1920s. During the Iran–Iraq War, Iraq bombed many of Iran's petrochemical plants, damaging the large oil refinery at Abadan bringing production to a halt. Reconstruction began in 1988 and production resumed in 1993. In spite of the war, many small factories sprang up to produce import-substitution goods and materials needed by the military.[citation needed]

Iran's major manufactured products are petrochemicals, steel and copper products. Other important manufactures include automobiles, home and electric appliances, telecommunications equipment, cement and industrial machinery. Iran operates the largest operational population of industrial robots in West Asia.[274] Other products include paper, rubber products, processed foods, leather products and pharmaceuticals. In 2000, textile mills, using domestic cotton and wool such as Tehran Patou and Iran Termeh employed around 400,000 people around Tehran, Isfahan and along the Caspian coast.[275][276]

A 2003 report by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization regarding small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)[217] identified the following impediments to industrial development:

- Lack of monitoring institutions;

- Inefficient banking system;

- Insufficient research & development;

- Shortage of managerial skills;

- Corruption;

- Inefficient taxation;

- Socio-cultural apprehensions;

- Absence of social learning loops;

- Shortcomings in international market awareness necessary for global competition;

- Cumbersome bureaucratic procedures;

- Shortage of skilled labor;

- Lack of intellectual property protection;

- Inadequate social capital, social responsibility and socio-cultural values.

Despite these problems, Iran has progressed in various scientific and technological fields, including petrochemical, pharmaceutical, aerospace, defense, and heavy industry. Even in the face of economic sanctions, Iran is emerging as an industrialized country.[277]

Handicrafts

Iran has a long tradition of producing artisanal goods including Persian carpets, ceramics, copperware, brassware, glass, leather goods, textiles and wooden artifacts. The country's carpet-weaving tradition dates from pre-Islamic times and remains an important industry contributing substantial amounts to rural incomes. An estimated 1.2 million weavers in Iran produce carpets for domestic and international export markets.[citation needed] More than $500 million worth of hand-woven carpets are exported each year, accounting for 30% of the 2008 world market.[278][279] Around 5.2 million people work in some 250 handicraft fields and contribute 3% of GDP.[citation needed]

Automobile manufacturing

As of 2001, 13 public and privately owned automakers within Iran, led by Iran Khodro and Saipa that accounted for 94% of domestic production. Iran Khodro's Paykan, replaced by the Samand in 2005, is the predominant brand. With 61% of the 2001 market, Khodro was the largest player, whilst Saipa contributed 33% that year. Other car manufacturers, such as the Bahman Group, Kerman Motors, Kish Khodro, Raniran, Traktorsazi, Shahab Khodro and others accounted for the remaining 6%.[280]

These automakers produce a wide range of vehicles including motorbikes, passenger cars such as Saipa's Tiba, vans, mini trucks, medium-sized trucks, heavy trucks, minibuses, large buses and other heavy automobiles used for commercial and private activities in the country. In 2009 Iran ranked fifth in car production growth after China, Taiwan, Romania and India.[281] Iran was the world's 12th biggest automaker in 2010 and operates a fleet of 11.5 million cars.[282][283][284][285] Iran produced 1,395,421 cars in 2010, including 35,901 commercial vehicles.[citation needed]

Defense industry

In 2007 the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated Iran's defense budget at $7.31 billion, equivalent to 2.6% of GDP or $102 per capita, ranking it 25th internationally. The country's defense industry manufactures many types of arms and equipment. Since 1992, Iran's Defense Industries Organization (DIO) has produced its own tanks, armored personnel carriers, guided missiles, radar systems, guided missile destroyers, military vessels, submarines and fighter planes.[286] In 2006 Iran exported weapons to 57 countries, including NATO members, and exports reached $100 million.[287][288] It has also developed a sophisticated mobile air defense system dubbed as Bavar 373.[289]

Construction and real estate

Until the early 1950s construction remained in the hands of small domestic companies. Increased income from oil and gas and easy credit triggered a building boom that attracted international construction firms to the country. This growth continued until the mid-1970s when a sharp rise in inflation and a credit squeeze collapsed the boom. The construction industry had revived somewhat by the mid-1980s, although housing shortages and speculation remained serious problems, especially in large urban centers. As of January 2011, the banking sector, particularly Bank Maskan, had loaned up to 102 trillion rials ($10.2 billion) to applicants of Mehr housing scheme.[290] Construction is one of the most important sectors accounting for 20–50% of total private investment in urban areas and was one of the prime investment targets of well-off Iranians.[259]

Annual turnover amounted to $38.4 billion in 2005 and $32.8 billion in 2011.[291][292] Because of poor construction quality, many buildings need seismic reinforcement or renovation.[293] Iran has a large dam building industry.[294]

Mines and metals

Mineral production contributed 0.6% of the country's GDP in 2011,[citation needed] a figure that increases to 4% when mining-related industries are included. Gating factors include poor infrastructure, legal barriers, exploration difficulties, and government control over all resources.[296] Iran is ranked among the world's 15 major mineral-rich countries.[297]

Although the petroleum industry provides the majority of revenue, about 75% of all mining sector employees work in mines producing minerals other than oil and natural gas.[70] These include coal, iron ore, copper, lead, zinc, chromium, barite, salt, gypsum, molybdenum, strontium, silica, uranium, and gold, the latter of which is mainly a by-product of the Sar Cheshmeh copper complex operation.[298] The mine at Sar Cheshmeh in Kerman Province is home to the world's second largest store of copper.[299] Large iron ore deposits exist in central Iran, near Bafq, Yazd and Kerman. The government owns 90% of all mines and related industries and is seeking foreign investment.[296] The sector accounts for 3% of exports.[296]

In 2019, the country was the 2nd largest world producer of gypsum;[300] the 8th largest world producer of molybdenum;[301] the world's 8th largest producer of antimony;[302] the 11th largest world producer of iron ore;[303] the 18th largest world producer of sulfur,[304] in addition to being the 21st largest worldwide producer of salt.[305] It was the 13th largest producer in the world of uranium in 2018.[306]

Iran has recoverable coal reserves of nearly 1.9 billion short tonnes. By mid-2008, the country produced about 1.3 million short tonnes of coal annually and consumed about 1.5 million short tonnes, making it a net importer.[307] The country plans to increase hard-coal production to 5 million tons in 2012 from 2 million tons in November 2008.[308]

The main steel mills are located in Isfahan and Khuzestan. Iran became self-sufficient in steel in 2009.[309] Aluminum and copper production are projected to hit 245,000 and 383,000 tons respectively by March 2009.[308][310] Cement production reached 65 million tons in 2009, exporting to 40 countries.[310][311]

Petrochemicals

Iran manufactures 60–70% of its equipment domestically, including refineries, oil tankers, drilling rigs, offshore platforms, and exploration instruments.[312][313][314][315]

Based on a fertilizer plant in Shiraz, the world's largest ethylene unit, in Asalouyeh, and the completion of other special economic zone projects, Iran's exports in petrochemicals reached $5.5 billion in 2007, $9 billion in 2008 and $7.6 billion during the first ten months of the Iranian calendar year 2010.[316] National Petrochemical Company's output capacity will increase to over 100 million tpa by 2015 from an estimated 50 million tpa in 2010 thus becoming the world' second largest chemical producer globally after Dow Chemical with Iran housing some of the world's largest chemical complexes.[123]

Major refineries located at Abadan (site of its first refinery), Kermanshah and Tehran failed to meet domestic demand for gasoline in 2009. Iran's refining industry requires $15 billion in investment over the period 2007–2012 to become self-sufficient and end gasoline imports.[317] Iran has the fifth cheapest gasoline prices in the world leading to fuel smuggling with neighboring countries.[318]

In November 2019, Iran raised the gasoline prices by 50% and imposed a strict rationing system again, as in 2007. The prices per liter gasoline rose to 15,000 rials, where only 60 liters were permitted to private cars for a month. Besides, oil purchase beyond the limit would cost 30,000 rials per liter. Those prices are still well below target prices set in the subsidy reform plan, however. The policy changes came in effect to the US sanctions, and caused protests across the country.[319] The result of the rationing, a year later, was reduced pollution and wasteful domestic consumption and increase in exports.[320]

Services

Despite 1990s efforts towards economic liberalization, government spending, including expenditure by quasi-governmental foundations, remains high. Estimates of service sector spending in Iran are regularly more than two-fifths of GDP, much government-related, including military expenditures, government salaries, and social security disbursements.[38] Urbanization contributed to service sector growth. Important service industries include public services (including education), commerce, personal services, professional services and tourism.

The total value of transport and communications is expected to rise to $46 billion in nominal terms by 2013, representing 6.8% of Iran's GDP.[321] Projections based on 1996 employment figures compiled for the International Labour Organization suggest that Iran's transport and communications sector employed 3.4 million people, or 20.5% of the labor force in 2008.[321]

Energy, gas, and petroleum

- production: 258 billion kWh (2014)

- consumption: 218 billion kWh (2014)

- exports: 9.7 billion kWh (2014)

- imports: 3.8 billion kWh (2014)

Electricity – production by source:

- fossil fuels: 85.6% (2012)

- hydro: 12.4% (2012)

- other: 0.8% (2012)

- nuclear: 1.2% (2012)

Oil:

- production: 3,300,000 bbl/d (520,000 m3/d) (2015)

- exports: 1,042,000 bbl/d (165,700 m3/d) (2013)

- imports: 87,440 bbl/d (13,902 m3/d) (2013)

- proved reserves: 157.8 Gbbl (25.09×109 m3) (2016)

Natural gas:

- production: 174.5 km3 (2014)

- consumption: 170.2 km3 (2014)

- exports: 9.86 km3 (2014)

- imports: 6.886 km3 (2014)

- proved reserves: 34,020 km3 (2016)

Iran possesses 10% of the world's proven oil reserves and 15% of its gas reserves.[27] Domestic oil and gas along with hydroelectric power facilities provide power.[27] Energy wastage in Iran amounts to six or seven billion dollars per year,[323] much higher than the international norm.[103] Iran recycles 28% of its used oil and gas, whereas some other countries reprocess up to 60%.[323] In 2008 Iran paid $84 billion in subsidies for oil, gas and electricity.[35] It is the world's third largest consumer of natural gas after United States and Russia.[38] In 2010 Iran completed its first nuclear power plant at Bushehr with Russian assistance.[324]

Iran has been a major oil exporter since 1913. The country's major oil fields lie in the central and southwestern parts of the western Zagros mountains. Oil is also found in northern Iran and in the Persian Gulf. In 1978, Iran was the fourth largest oil producer, OPEC's second largest oil producer and second largest exporter.[325] Following the 1979 revolution the new government reduced production. A further decline in production occurred as result of damage to oil facilities during the Iraq-Iran war.[326]

Oil production rose in the late 1980s as pipelines were repaired and new Gulf fields exploited. By 2004, annual oil production reached 1.4 billion barrels producing a net profit of $50 billion.[326] Iranian Central Bank data show a declining trend in the share of Iranian exports from oil-products (FY 2006: 84.9%, 2007/2008: 86.5%, 2008/2009: 85.5%, 2009/2010: 79.8%, FY 2010 (first three quarters): 78.9%).[327] Iranian officials estimate that Iran's annual oil and gas revenues could reach $250 billion by 2015 once current projects come on stream.[117]

Pipelines move oil from the fields to the refineries and to such exporting ports as Abadan, Bandar-e Mashur and Kharg Island. Since 1997, Iran's state-owned oil and gas industry has entered into major exploration and production agreements with foreign consortia.[328][329] In 2008 the Iranian Oil Bourse (IOB) was inaugurated in Kish Island.[330] The IOB trades petroleum, petrochemicals and gas in various currencies. Trading is primarily in the euro and rial along with other major currencies, not including the US dollar.[citation needed] According to the Petroleum Ministry, Iran plans to invest $500 billion in its oil sector by 2025.[331]

As of August 2025 the crude oil price declined by 15.44% since August 2024.[332] In addition, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says global demand in 2025 is expected to grow by less than 700,000 barrels per day (bpd), while supply is set to rise by 2.5 million bpd— resulting in a surplus of more than 1.8 million bpd and consequently, a further decline in oil price is expected.[333] The decline of oil price is expected to further aggravate Iran's economic situation since Iran is heavily dependent on Chinese refiners that take advantage on Iran's difficulties to sell oil in the global markets.[333]

Retail and distribution

Iran's retail industry consists largely of cooperatives (many of them government-sponsored), and independent retailers operating in bazaars. The bulk of food sales occur at street markets with prices set by the Chief Statistics Bureau. Iran has 438,478 small grocery retailers.[334] These are especially popular in cities other than Tehran where the number of hypermarkets and supermarkets is still very limited. More mini-markets and supermarkets are emerging, mostly independent operations. The biggest chainstores are state-owned Etka, Refah, Shahrvand and Hyperstar Market.[334] Electronic commerce in Iran passed the $1 billion mark in 2009.[335]

In 2012, Iranians spent $77 billion on food, $22 billion on clothes and $18.5 billion on outward tourism.[336] In 2015, overall consumer spending and disposable income are projected at $176.4 billion and $287 billion respectively.[337]

Healthcare and pharma

The constitution entitles Iranians to basic health care. By 2008, 73% of Iranians were covered by the voluntary national health insurance system.[338] Although over 85% of the population use an insurance system to cover their drug expenses, the government heavily subsidizes pharmaceutical production/importation. The total market value of Iran's health and medical sector was $24 billion in 2002 and was forecast to rise to $50 billion by 2013.[339][340] In 2006, 55 pharmaceutical companies in Iran produced 96% (quantitatively) of the medicines for a market worth $1.2 billion.[338][341][342] This figure is projected to increase to $3.65 billion by 2013.[340]

According to Hataminia, S., & Mohammadzadeh Asl, N. (2025), the deteriorating economic indicator of Iran especially, inflation and unemployment rates exert significant negative effects on life expectancy.[343]

Tourism and travel

Although tourism declined significantly during the war with Iraq, it has subsequently recovered. About 1,659,000 foreign tourists visited Iran in 2004 and 2.3 million in 2009 mostly from Asian countries, including the republics of Central Asia, while about 10% came from the European Union and North America.[81][344]

The most popular tourist destinations are Mazandaran, Isfahan, Mashhad and Shiraz.[345] In the early 2000s the industry faced serious limitations in infrastructure, communications, industry standards and personnel training.[266] Several organized tours from Germany, France and other European countries come to Iran annually to visit archaeological sites and monuments. In 2003 Iran ranked 68th in tourism revenues worldwide.[346] According to UNESCO and the deputy head of research for Iran Travel and Tourism Organization (ITTO), Iran is rated among the "10 most touristic countries in the world".[346] Domestic tourism in Iran is one of the largest in the world.[347]

Banking, finance and insurance

Government loans and credits are available to industrial and agricultural projects, primarily through banks. Iran's unit of currency is the rial which had an average official exchange rate of 9,326 rials to the U.S. dollar in 2007.[38] Rials are exchanged on the unofficial market at a higher rate. In 1979, the government nationalized private banks. The restructured banking system replaced interest on loans with handling fees, in accordance with Islamic law. This system took effect in the mid-1980s.[56]

The banking system consists of a central bank, the Bank Markazi, which issues currency and oversees all state and private banks, as well as the Organization of Islamic Economics which acts as a sort of central bank for issuing Qard al-Hasan, as a parallel system in the banking sector, operating outside the purview of the Central Bank.[93] It supervises 1200, out of 2500 Islamic loan funds, on behalf of Iran's Central Bank.[350] Several commercial banks have branches throughout the country. Two development banks exist and a housing bank specializes in home mortgages. The government began to privatize the banking sector in 2001 when licenses were issued to two new privately owned banks.[351]

State-owned commercial banks predominantly make loans to the state, bonyad enterprises, large-scale private firms and four thousand wealthy/connected individuals.[352][353] While most Iranians have difficulty obtaining small home loans, 90 individuals secured facilities totaling $8 billion.[citation needed] In 2009, Iran's General Inspection Office announced that Iranian banks held some $38 billion of delinquent loans, with capital of only $20 billion.[citation needed]

Foreign transactions with Iran amounted to $150 billion of major contracts between 2000 and 2007, including private and government lines of credit.[354] In 2007, Iran had $62 billion in assets abroad.[355] In 2010, Iran attracted almost $11.9 billion from abroad, of which $3.6 billion was FDI, $7.4 billion was from international commercial bank loans, and around $900 million consisted of loans and projects from international development banks.[356]

As of 2010, the Tehran Stock Exchange traded the shares of more than 330 registered companies.[349] Listed companies were valued at $100 billion in 2011.[357]

Insurance premiums accounted for just under 1% of GDP in 2008,[307] a figure partly attributable to low average income per head.[307] Five state-owned insurance firms dominate the market, four of which are active in commercial insurance. The leading player is the Iran Insurance Company, followed by Asia, Alborz and Dana insurances. In 2001/02 third-party liability insurance accounted for 46% of premiums, followed by health insurance (13%), fire insurance (10%) and life insurance (9.9%).[351]

Communications, electronics and IT

Broadcast media, including five national radio stations and five national television networks as well as dozens of local radio and television stations are run by the government. In 2008, there were 345 telephone lines and 106 personal computers for every 1,000 residents.[358] Personal computers for home use became more affordable in the mid-1990s, since when demand for Internet access has increased rapidly. As of 2010, Iran also had the world's third largest number of bloggers (2010).[359]

In 1998, the Ministry of Post, Telegraph & Telephone, later renamed the Ministry of Information & Communication Technology, began selling Internet accounts to the general public. In 2006, revenues from the Iranian telecom industry were estimated at $1.2 billion.[360] In 2006, Iran had 1,223 Internet Service Providers (ISPs), all private sector operated.[361] As of 2014, Iran has the largest mobile market in the Middle East, with 83.2 million mobile subscriptions and 8 million smart-phones in 2012.[362]

According to the World Bank, Iran's information and communications technology sector had a 1.4% share of GDP in 2008.[358] Around 150,000 people work in this sector, including 20,000 in the software industry.[363] 1,200 IT companies were registered in 2002, 200 in software development. In 2014 software exports stood at $400 million.[citation needed] By the end of 2009, Iran's telecom market was the fourth-largest in the Middle East at $9.2 billion and was expected to reach $12.9 billion by 2014 at a compound annual growth rate of 6.9%.[364]

Transport

Iran has an extensive paved road system linking most towns and all cities. In 2011, the country had 173,000 kilometres (107,000 mi) of roads, of which 73% were paved. In 2007 there were approximately 100 passenger cars for every 1,000 inhabitants.[282] Trains operated on 11,106 kilometres (6,901 mi) of track.[38]

Iran's major port of entry is Bandar-Abbas on the Strait of Hormuz. After arriving in Iran, imported goods are distributed by trucks and freight trains. The Tehran–Bandar-Abbas railroad, opened in 1995, connects Bandar-Abbas to Central Asia via Tehran and Mashhad. Other major ports include Bandar Anzali and Bandar Torkaman on the Caspian Sea and Khoramshahr and Bandar Imam Khomeini on the Persian Gulf.

Dozens of cities have passenger and cargo airports. Iran Air, the national airline, was founded in 1962 and operates domestic and international flights. All large cities have bus transit systems and private companies provide intercity bus services. Tehran, Mashhad, Shiraz, Tabriz, Ahvaz and Isfahan are constructing underground railways. More than one million people work in the transportation sector, accounting for 9% of 2008 GDP.[365]

In August 2022, President Ebrahim Raisi's cabinet approved a law to import fully assembled foreign cars. His predecessor President Hassan Rouhani, had outlawed such imports in July 2018 due to sanctions imposed on Iran. Regular Iranian citizens were unable to buy safe cars at affordable prices.[366]

International trade

Summarize

Perspective

Iran is a founding member of OPEC and the Organization of Gas Exporting Countries.[367] Petroleum constitutes 56% of Iran's exports with a value of $60.2 billion in 2018.[17] For the first time, the value of Iran's non-oil exports is expected to reach the value of imports at $43 billion in 2011.[368] Pistachios, liquefied propane, methanol (methyl alcohol), hand-woven carpets and automobiles are the major non-oil exports.[369] Copper, cement, leather, textiles, fruits, saffron and caviar are also export items of Iran.

Technical and engineering service exports in FY 2007 were $2.7 billion of which 40% of technical services went to Central Asia and the Caucasus, 30% ($350 million) to Iraq, and close to 20% ($205 million) to Africa.[370] Iranian firms have developed energy, pipelines, irrigation, dams and power generation in different countries. The country has made non-oil exports a priority[107] by expanding its broad industrial base, educated and motivated workforce and favorable location, which gives it proximity to an estimated market of some 300 million people in Caspian, Persian Gulf and some ECO countries further east.[371][372]

Total import volume rose by 189% from $13.7 billion in 2000 to $39.7 billion in 2005 and $55.189 billion in 2009.[373] Iran's major commercial partners are China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, and South Korea. From 1950 until 1978, the United States was Iran's foremost economic and military partner, playing a major role in infrastructure and industry modernization.[57][58] It is reported that around 80% of machinery and equipment in Iran is of German origin.[374] In March 2018, Iran had banned Dollar in trade.[375] In July 2018, France, Germany and the UK agreed to continue trade with Iran without using Dollar as a medium of exchange.[376]

Since the mid-1990s, Iran has increased its economic cooperation with other developing countries in "South–South integration" including Syria, India, China, South Africa, Cuba, and Venezuela. Iran's trade with India passed $13 billion in 2007, an 80% increase within a year.[citation needed] Iran is expanding its trade ties with Turkey and Pakistan and shares with its partners the common objective to create a common market in West and Central Asia through ECO.[citation needed]

Since 2003, Iran has increased investment in neighboring countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan. In Dubai, UAE, it is estimated that Iranian expatriates handle over 20% of its domestic economy and account for an equal proportion of its population.[378][379] Migrant Iranian workers abroad remitted less than $2 billion home in 2006.[380] Between 2005 and 2009, trade between Dubai and Iran tripled to $12 billion; money invested in the local real estate market and import-export businesses, collectively known as the Bazaar, and geared towards providing Iran and other countries with required consumer goods.[381] It is estimated that one third of Iran's imported goods and exports are delivered through the black market, underground economy, and illegal jetties, thus damaging the economy.[207]

The current account

Iran had an estimated $110 billion in foreign reserves in 2011[169] and balances its external payments by pricing oil at approximately $75 per barrel.[170] As of 2013, only $30 to $50 billion of those reserves are accessible because of current sanctions.[171] Iranian media has questioned the reason behind Iran's government non-repatriation of its foreign reserves before the imposition of the latest round of sanctions and its failure to convert into gold. As a consequence, the Iranian rial lost more than 40% of its value between December 2011 and April 2012.[142]

The current account was expected to reach a surplus of 2.1% of GDP in FY 2012, and the net fiscal balance (after payments to Iran's National Development Fund) will register a surplus of 0.3% of GDP.[76] In 2013 the external debts stood at $7.2 billion down from $17.3 billion in 2012.[172] Overall fiscal deficit is expected to deteriorate to 2.7% of GDP in FY 2016 from 1.7% in 2015.[173]

Money in circulation reached $700 billion in March 2020 (based on the 2017 pre-devaluation exchange rate), thus furthering the decline of the Iranian rial and rise in inflation.[174][175]

Foreign direct investment

In the 1990s and early 2000s, indirect oilfield development agreements were made with foreign firms, including buyback contracts in the oil sector whereby the contractor provided project finance in return for an allocated production share. Operation transferred to National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) after a set number of years, completing the contract.[382]

Unfavorable or complex operating requirements and international sanctions have hindered foreign investment in the country, despite liberalization of relevant regulations in the early 2000s. Iran absorbed $24.3 billion of foreign investment between the Iranian calendar years 1993 and 2007.[383] The EIU estimates that Iran's net FDI will rise by 100% between 2010 and 2014.[384]

Foreign investors concentrated their activities in the energy, vehicle manufacture, copper mining, construction, utilities, petrochemicals, clothing, food and beverages, telecom and pharmaceuticals sectors. Iran is a member of the World Bank's Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.[385] In 2006, the combined net worth of Iranian citizens abroad was about 1.3 trillion dollars.[386]