Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Paganism

Polytheistic religious groups From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

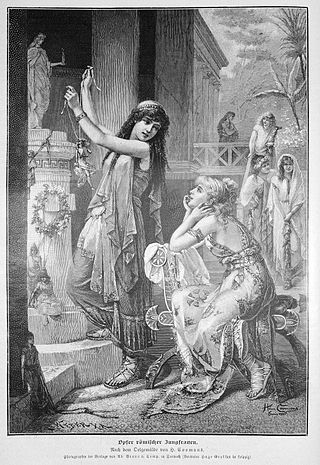

Paganism (from Latin paganus 'rural, rustic', later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism,[1] or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the Roman Empire, individuals fell into the pagan class either because they were increasingly rural and provincial relative to the Christian population, or because they were not milites Christi (soldiers of Christ).[2][3] Alternative terms used in Christian texts were hellene, gentile, and heathen.[1] Ritual sacrifice was an integral part of ancient Greco-Roman religion[4] and was regarded as an indication of whether a person was pagan or Christian.[4] Paganism has broadly connoted the "religion of the peasantry".[1][5]

During and after the Middle Ages, the term paganism was applied to any non-Christian religion, and the term presumed a belief in false gods.[6][7] The origin of the application of the term "pagan" to polytheism is debated.[8] In the 19th century, paganism was adopted as a self-descriptor by members of various artistic groups inspired by the ancient world. In the 20th century, it came to be applied as a self-descriptor by practitioners of modern paganism, modern pagan movements and polytheistic reconstructionists. Modern pagan traditions often incorporate beliefs or practices, such as nature worship, that are different from those of the largest world religions.[9][10]

Contemporary knowledge of old pagan religions and beliefs comes from several sources, including anthropological field research, the evidence of archaeological artifacts, the philology of ancient language, and the historical accounts of ancient writers regarding cultures known to Classical antiquity. Most modern pagan religions existing today express a worldview that is polytheistic, pantheistic, panentheistic, or animistic, but some are monotheistic.[11][12][13]

Remove ads

Etymology and nomenclature

Summarize

Perspective

Pagan

It is crucial to stress right from the start that until the 20th century, people did not call themselves pagans to describe the religion they practiced. The notion of paganism, as it is generally understood today, was created by the early Christian Church. It was a label that Christians applied to others, one of the antitheses that were central to the process of Christian self-definition. As such, throughout history it was generally used in a derogatory sense.

— Owen Davies, Paganism: A Very Short Introduction, 2011[14]

The term pagan derives from Late Latin paganus, revived during the Renaissance. Itself deriving from classical Latin pagus which originally meant 'region delimited by markers', paganus had also come to mean 'of or relating to the countryside', 'country dweller', 'villager'; by extension, 'rustic', 'unlearned', 'yokel', 'bumpkin'; in Roman military jargon, 'non-combatant', 'civilian', 'unskilled soldier'. It is related to pangere ('to fasten', 'to fix or affix') and ultimately comes from Proto-Indo-European *pag- ('to fix' in the same sense):[15]

The adoption of paganus by the Latin Christians as an all-embracing, pejorative term for polytheists represents an unforeseen and singularly long-lasting victory, within a religious group, of a word of Latin slang originally devoid of religious meaning. The evolution occurred only in the Latin west, and in connection with the Latin church. Elsewhere, Hellene or gentile (ethnikos) remained the word for pagan; and paganos continued as a purely secular term, with overtones of the inferior and the commonplace.

— Peter Brown, Late Antiquity, 1999[16]

Medieval writers often assumed that paganus as a religious term was a result of the conversion patterns during the Christianization of Europe, where people in towns and cities were converted more easily than those in remote regions, where old ways tended to remain. However, this idea has multiple problems. First, the word's usage as a reference to non-Christians pre-dates that period in history. Second, paganism within the Roman Empire centred on cities. The concept of an urban Christianity as opposed to a rural paganism would not have occurred to Romans during Early Christianity. Third, unlike words such as rusticitas, paganus had not yet fully acquired the meanings (of uncultured backwardness) used to explain why it would have been applied to pagans.[17]

Paganus more likely acquired its meaning in Christian nomenclature via Roman military jargon (see above). Early Christians adopted military motifs and saw themselves as Milites Christi (soldiers of Christ).[15][17] A good example of Christians still using paganus in a military context rather than a religious one is in Tertullian's De Corona Militis XI.V, where the Christian is referred to as paganus (civilian):[17]

| Apud hunc [Christum] tam miles est paganus fidelis quam paganus est miles fidelis.[18] | With Him [Christ] the faithful citizen is a soldier, just as the faithful soldier is a citizen.[19] |

Paganus acquired its religious connotations by the mid-4th century.[17] As early as the 5th century, paganos was metaphorically used to denote persons outside the bounds of the Christian community. Following the sack of Rome by the Visigoths just over fifteen years after the Christian persecution of paganism under Theodosius I,[20] murmurs began to spread that the old gods had taken greater care of the city than the Christian God. In response, Augustine of Hippo wrote De Civitate Dei Contra Paganos ('The City of God against the Pagans'). In it, he contrasted the fallen "city of Man" with the "city of God", of which all Christians were ultimately citizens. Hence, the foreign invaders were "not of the city" or "rural".[21][22][23]

The term pagan was not attested in the English language until the 17th century.[24] In addition to infidel and heretic, it was used as one of several pejorative Christian counterparts to goy (גוי / נכרי) as used in Judaism, and to kafir (كافر, 'unbeliever') and mushrik (مشرك, 'idolater') as in Islam.[25]

Hellene

In the Latin-speaking Western Roman Empire of the newly Christianizing Roman Empire, Koine Greek became associated with the traditional polytheistic religion of Ancient Greece and was regarded as a foreign language (lingua peregrina) in the west.[26] By the latter half of the 4th century in the Greek-speaking Eastern Empire, pagans were—paradoxically—most commonly called Hellenes (Ἕλληνες, lit. "Greeks") The word had almost entirely ceased being used in a cultural sense.[27][28] It retained that meaning for roughly the first millennium of Christianity.

This was influenced by Christianity's early members, who were Jewish. The Jews of the time distinguished themselves from foreigners according to religion rather than ethno-cultural standards, and early Jewish Christians would have done the same. Since Hellenic culture was the dominant pagan culture in the Roman east, they referred to pagans as Hellenes. Christianity inherited Jewish terminology for non-Jews and adapted it to refer to non-Christians with whom they were in contact. This usage is recorded in the New Testament. In the Pauline epistles, Hellene is almost always juxtaposed with Hebrew regardless of actual ethnicity.[28]

The usage of Hellene as a religious term was initially part of an exclusively Christian nomenclature, but some Pagans began to defiantly call themselves Hellenes. Other pagans even preferred the narrow meaning of the word from a broad cultural sphere to a more specific religious grouping. However, there were many Christians and pagans alike who strongly objected to the evolution of the terminology. The influential Archbishop of Constantinople Gregory of Nazianzus, for example, took offence at imperial efforts to suppress Hellenic culture (especially concerning spoken and written Greek) and he openly criticized the emperor.[27]

The growing religious stigmatization of Hellenism had a chilling effect on Hellenic culture by the late 4th century.[27]

By late antiquity, however, it was possible to speak Greek as a primary language while not conceiving of oneself as a Hellene.[29] The long-established use of Greek both in and around the Eastern Roman Empire as a lingua franca ironically allowed it to instead become central in enabling the spread of Christianity—as indicated for example, by the use of Greek for the Epistles of Paul.[30] In the first half of the 5th century, Greek was the standard language in which bishops communicated,[31] and the Acta Conciliorum ("Acts of the Church Councils") were recorded originally in Greek and then translated into other languages.[32]

Heathen

"Heathen" comes from Old English: hæðen (not Christian or Jewish); cf. Old Norse heiðinn. This meaning for the term originated from Gothic haiþno (gentile woman) being used to translate Hellene[33] in Wulfila's Bible, the first translation of the Bible into a Germanic language. This may have been influenced by the Greek and Latin terminology of the time used for pagans. If so, it may be derived from Gothic haiþi (dwelling on the heath). However, this is not attested. It may even be a borrowing of Greek ἔθνος (ethnos) via Armenian hethanos.[34]

The term has recently been revived in the forms "Heathenry" and "Heathenism" (often but not always capitalized), as alternative names for the modern Germanic pagan movement, adherents of which may self-identify as Heathens.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Definition

Summarize

Perspective

It is perhaps misleading even to say that there was such a religion as paganism at the beginning of [the Common Era] ... It might be less confusing to say that the pagans, before their competition with Christianity, had no religion at all in the sense in which that word is normally used today. They had no tradition of discourse about ritual or religious matters (apart from philosophical debate or antiquarian treatise), no organized system of beliefs to which they were asked to commit themselves, no authority-structure peculiar to the religious area, above all no commitment to a particular group of people or set of ideas other than their family and political context. If this is the right view of pagan life, it follows that we should look on paganism quite simply as a religion invented in the course of the second to third centuries AD, in competition and interaction with Christians, Jews and others.

— J A North 1992, 187–88, [35]

Defining paganism is very complex and problematic. Understanding the context of its associated terminology is important.[36] Early Christians referred to the diverse array of cults around them as a single group for reasons of convenience and rhetoric.[37] While paganism generally implies polytheism, the primary distinction between classical pagans and Christians was not one of monotheism versus polytheism, as not all pagans were strictly polytheist. Throughout history, many of them believed in a supreme deity. However, most such pagans believed in a class of subordinate gods/daimons—see henotheism—or divine emanations.[13] To Christians, the most important distinction was whether or not someone worshipped the one true God. Those who did not (polytheist, monotheist, or atheist) were outsiders to the Church and thus considered pagan.[38] Similarly, classical pagans would have found it peculiar to distinguish groups by the number of deities followers venerate. They would have considered the priestly colleges (such as the College of Pontiffs or Epulones) and cult practices more meaningful distinctions.[39]

Referring to paganism as a pre-Christian indigenous religion is equally untenable. Not all historical pagan traditions were pre-Christian or indigenous to their places of worship.[36]

Owing to the history of its nomenclature, paganism traditionally encompasses the collective pre- and non-Christian cultures in and around the classical world; including those of the Greco-Roman, Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic tribes.[40] However, modern parlance of folklorists and contemporary pagans in particular has extended the original four millennia scope used by early Christians to include similar religious traditions stretching far into prehistory.[41]

Remove ads

Perception and Ethnocentrism

Paganism came to be equated by Christians with a sense of hedonism, representing those who are sensual, materialistic, self-indulgent, unconcerned with the future, and uninterested in more mainstream religions. Pagans were usually described in terms of this worldly stereotype, especially among those drawing attention to what they perceived as the limitations of paganism.[42]

Recently, the ethnocentric and moral absolutist origins of the common usage of the term pagan have been proposed,[43][44] with scholar David Petts noting how, with particular reference to Christianity, "...local religions are defined in opposition to privileged 'world religions'; they become everything that world religions are not, rather than being explored as a subject in their own right."[45] In addition, Petts notes how various spiritual, religious, and metaphysical ideas branded as "pagan" from diverse cultures were studied in opposition to Abrahamism in early anthropology, a binary he links to ethnocentrism and colonialism.[46]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Prehistoric

Bronze Age to Early Iron Age

Ancient history

Classical antiquity

Ludwig Feuerbach defined the paganism of classical antiquity, which he termed Heidentum ('heathenry') as "the unity of religion and politics, of spirit and nature, of god and man",[47] qualified by the observation that man in the pagan view is always defined by ethnicity, i.e., As a result, every pagan tradition is also a national tradition. Modern historians define paganism instead as the aggregate of cult acts, set within a civic rather than a national context, without a written creed or sense of orthodoxy.[48]

Late Antiquity

Pagan as a religious concept arose out of the development of Christianity, as an exonym to refer to certain non-Christian peoples and practices, both at the center of and in the outer reaches of the Roman Empire.

Early Christianity was one of several monotheistic cults within the Roman Empire, emerging from Second Temple Judaism and Hellenistic Judaism. It developed in context, relationship, and competition with other religions advocating both monotheism and polytheism. Early Christianity distinguished itself from these other religions through the concept of paganism, naming those "pagan" who did not worship "the one true God".

Notable monotheistic cults contemporary with Early Christianity included those of Dionysus,[49] Neoplatonism, Mithraism, Gnosticism, and Manichaeanism.[citation needed] The cult of Dionysus is thought to have strongly influenced Early Christian themes, and is an example of how Christianity defined itself against "paganism" while incorporating "pagan" religious themes and practices. Numerous scholars have concluded that the conceptual construction of Jesus the wandering rabbi into the image of Christ the Logos, reflects direct influence from the cult of Dionysus, and the symbolism of wine and the importance it held in the mythology surrounding both Dionysus and Jesus Christ exemplifies this.[50][51] Peter Wick argues that the use of wine symbolism in the Gospel of John, including the story of the Marriage at Cana at which Jesus turns water into wine, was intended to show Jesus as superior to Dionysus.[52] The scene in The Bacchae wherein Dionysus appears before King Pentheus on charges of claiming divinity can be compared to the New Testament scene of Jesus being interrogated by Pontius Pilate.[52][53][54]

In Albania

Paganism in Albania serves as an example of how indigenous folk religious practices persisted under official policies of Christian conversion. Proto-Albanian speakers were Christianized under the Latin sphere of influence, specifically in the 4th century CE, as shown by the basic Christian terms in Albanian, which are of Latin origin and entered Proto-Albanian before the Gheg–Tosk dialectal diversification.[56][57] Regardless of Christianization, paganism persisted among Albanians, and especially within the inaccessible and deep interior[58] where Albanian folklore evolved over the centuries in a relatively isolated tribal culture and society.[59] It has continued to persist, despite partially transformation by Christian, and later Muslim and Marxist beliefs, that were either to be introduced by choice or imposed by force.[60] The Albanian traditional customary law (Kanun) has held a longstanding, unwavering, and sacred – although secular – unchallenged authority with a cross-religious effectiveness over the Albanians, which is attributed to an earlier pagan code common to all the Albanian tribes.[61] Historically, the Christian clergy has vigorously fought, but without success, to eliminate the pagan rituals practiced by Albanians for traditional feasts and particular events, especially the fire rituals (Zjarri).[62][63]

Postclassical history

The Byzantine lineage

Christianity was introduced late in Mani, with the first Greek temples converted into churches during the 11th century. Byzantine monk Nikon "the Metanoite" (Νίκων ὁ Μετανοείτε) was sent in the 10th century to convert the predominantly pagan Maniots. Although his preaching began the conversion process, it took over 200 years for the majority to accept Christianity fully by the 11th and 12th centuries. Patrick Leigh Fermor noted that the Maniots, isolated by mountains, were among the last Greeks to abandon the old religion, doing so towards the end of the 9th century:

Sealed off from outside influences by their mountains, the semi-troglodytic Maniots themselves were the last of the Greeks to be converted. They only abandoned the old religion of Greece towards the end of the ninth century. It is surprising to remember that this peninsula of rock, so near the heart of the Levant from which Christianity springs, should have been baptised three whole centuries after the arrival of St. Augustine in far-away Kent.[64]

According to Constantine VII in De Administrando Imperio, the Maniots were referred to as 'Hellenes' and only fully Christianized in the 9th century, despite some church ruins from the 4th century indicating early Christian presence. The region's mountainous terrain allowed the Maniots to evade the Eastern Roman Empire's Christianization efforts, thus preserving pagan traditions, which coincided with significant years in the life of Gemistos Plethon.

The End of the Athenian and Alexandrian Schools (5th–6th Century)

The continuity of classical philosophical thought, especially Neoplatonism and Aristotelianism, within the Byzantine Empire necessitated a strategic management of theological risk, given that the Hellenic tradition implied pagan cosmology and metaphysics contradicting Christian orthodoxy. Modern scholarship posits that key Byzantine intellectuals employed conscious strategies of intellectual accommodation, or oikonomia, which secured the transmission of non-Christian material, often discussed under the framework of crypto-pagan dissimulation.[65] These strategies allowed for the academic preservation of texts while publicly adhering to Christian orthodoxy.

The final generation of Neoplatonists established the survival strategies that would be inherited by Byzantium:

Proclus (412–485) and Damascius (458–538): As the successive heads of the Athenian School, both were overt practitioners of Hellenic paganism and Theurgy. The intellectual survival of their doctrines relied on structural abstraction: Proclus's systematic method in works like the Elements of Theology made him an indispensable philosophical quarry for later Christian theologians seeking a rigorous conceptual framework, thus ensuring his content's survival under the guise of intellectual utility.[66] Damascius, the last head of the school before its closure in 529, is implicated in the most radical act of dissimulation: the pseudepigraphy of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 500), which placed advanced Proclean Henology under apostolic authority, a strategy interpreted by scholars like Tuomo Lankila as a conscious "resurrect[ion of] the polytheistic religion" through concealment.[67]

Ammonius Hermiae (440–520): In Alexandria, Ammonius employed a pragmatic strategy of accommodation. Although a pagan, he negotiated with the Christian authorities (specifically the patriarch Proterius) to keep the school open, ensuring the continuous teaching of the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic curriculum. This public compliance allowed for the technical preservation of philosophical texts.[68]

Simplicius of Cilicia (6th century): Following the closure of the Athenian School, Simplicius moved to Persia. His immense commentaries on Aristotle served as a primary strategy of intellectual neutrality. By focusing on the historical and technical exposition of his predecessors' pagan arguments without overtly endorsing them, Simplicius became the essential vehicle for the objective transmission of Greek philosophy into the Byzantine and later Islamic worlds.[69]

Dionysius of Thrace (5th–6th century commentator): The tradition surrounding the Tékhnē grammatikḗ ensured the survival of pagan myth references within a dry, academic structure. Scholars note that the accompanying Christianized scholia (commentaries), written by Unknown early Byzantine commentators (7th–8th centuries), preserved the detailed mythological content, only adding perfunctory Christian disclaimers that did not meaningfully engage with or neutralize the pagan knowledge, thus ensuring its continuity.[70] This group of commentators are precursors to the later Aristotelian circle in Constantinople. Figures like John Philoponus (490–570), a student of Ammonius, also preserved Hellenism through the strategic refutation of pagan doctrines, such as in Against Proclus on the Eternity of the World, preserving the detailed philosophical arguments under the guise of neutralization.[71]

The Macedonian Renaissance and Komnenian Era (9th–12th Century)

The revival of scholarship formalized the use of disclaimers and political strategy:

Leo the Mathematician (c. 790–869) and Theodore of Smyrna (8th–9th century): Leo's promotion of advanced mathematics and Platonic-inspired thought while Archbishop and head of the Magnaura School led to explicit accusations of crypto-paganism from contemporaries, who charged him with "having rejected Christianity and adopted Greek paganism." His public disclaimers—or the political defenses he was forced to mount—were essential for his institutional survival.[72] Theodore of Smyrna, often cited as a student of Leo, participated in this transmission, though direct evidence of his own use of disclaimers is less prominent in scholarship.

Photius (c. 810–893) and Arethas of Caesarea (c. 860–935): Both utilized a strategy of archival preservation. Photius’s Myriobiblon preserved lost pagan philosophical and historical works by framing them as academic reviews.[73] Arethas’s patronage secured the physical copying of vital pagan texts, including Plato's dialogues. Arethas further used a political disclaimer by publicly attacking others (like Leo) for being "Hellenic," rhetorically distancing himself from the theological risk while actively enabling pagan scholarship.[74]

Michael Psellos (1017–1078): Psellos refined the strategy of the explicit disclaimer through dissimulation (oikonomia). He openly studied Proclus, Plotinus, and the Chaldaean Oracles, while publicly disavowing belief in pagan practices (like astrology) to "distance himself from heretical doctrines," a necessary facade to secure Hellenic philosophical concepts within the Christian educational system.[75]

John Italos (1025–1085), Eustratios of Nicaea (960–1030), and Michael of Ephesus (11th century): This group formed the core of the 11th-century Aristotelian circle. Italos's reliance on apodeictic proof over patristic authority was perceived as a failure of his disclaimers, leading to his condemnation and ten anathemas in 1082 for promoting "(crypto-)pagan" doctrines, recorded in the Synodikon of Orthodoxy.[76] Eustratios, his student, continued the tradition but his strategy of survival lay in focusing commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics (practical philosophy), a less theologically dangerous area, while Michael of Ephesus focused on monumentalizing the complete Aristotelian corpus (e.g., Parva Naturalia), a crucial act of systemic preservation for philosophical completeness.[77][78]

The Palaiologan Renaissance (13th–15th Century)

This final period saw renewed engagement with classical sources, requiring careful strategies to manage the transmission of volatile texts:

Gregory Choniades (c. 1240–1302) and Maximus Planudes (c. 1260–1330): Choniades's contribution was the importation of advanced Hellenic astronomical and mathematical knowledge from Persia. His strategy involved the technical translation of these texts into Greek, focusing on their empirical utility rather than their religious or philosophical implications, a form of intellectual compartmentalization aimed at protection.[79] Planudes, a grammarian, employed the strategy of literary preservation, compiling and commenting on potentially controversial texts, such as the Greek Anthology and Ptolemy's works, ensuring their survival through the guise of academic philology.[80]

Theodore Metochites (1270–1332): Metochites championed the preservation of classical science and philosophy through a strategy of apologetic structural integration. His literary projects employed sophisticated apologetic language, positioning pagan customs and prophecies as historical precursors fulfilled by Christian truth. This structure functioned as an overarching disclaimer that neutralized the theological threat of Hellenism through reinterpretation and "Hellenic-Christian synthesis."[81]

Georgios Gemistos Plethon (c. 1355–1452): Plethon was arguably the most radical proponent of Platonism in the Byzantine world. His intellectual survival strategy was based on radical dissimulation and secrecy: while publicly engaging in political and philosophical debates, he authored the Nómoi (Laws), a text that proposed a comprehensive, state-sanctioned neo-pagan, polytheistic religious system intended to replace Christianity in the reformed Byzantine state. Scholars view this concealed work as the ultimate statement of crypto-paganism, intended for a secret intellectual elite. The failure of this deep concealment led to its discovery after his death by Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios, who condemned Plethon and ordered the destruction by fire of the Nómoi, saving only the table of contents.[82][83]

The Arabic transmission

In the near east, the survival of specific technical and intellectual traditions from late antiquity, including advanced astrology, specialized mathematical techniques, and the corpus of Hermetic alchemy, was secured through organized non-Muslim communities integrated within the Arabic intellectual world.[84] This transmission route was centered on the non-Islamic community of the Sabians of Harran, who employed religious dissimulation (kitmān) while serving as essential scholars and translators.[85] Their technical expertise allowed them to preserve and transmit non-orthodox cosmological frameworks within scientific pursuits.[86]

Harran

The city of Harran served as a geographically and politically resilient center for a unique syncretic religion that blended Mesopotamian paganism with Neoplatonism.[87] This persistence allowed the community to function as a crucial hub for intellectual continuity well into the Abbasid period.[88]

Harran negotiated a peaceful surrender to the Rashidun Caliphate in 639–640.[89] The city gained particular political prominence under the Umayyad Caliph, Marwan II (r. 744–750), serving as his capital.[90] Although it later lost this status, its established schools and university flourished, actively participating in the Translation Movement during the reign of Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809).[91] Following a decree by Caliph Al-Ma'mun in 830, the community successfully adopted the protected legal status of "Sabians" mentioned in the Quran, ensuring the survival of their distinct religious and intellectual identity.[92]

The Sabian Core: Pagan Identity and Literary Transmission

The Sabians explicitly maintained a pagan identity, viewing their scientific and esoteric studies as integral to their religious practice.[93] Their devotion to the Chaldean-style astral cultus and their claim that Hermes Trismegistus was their primary prophet made them the natural custodians of the esoteric Greek and Babylonian scientific lineages.[94]

The most influential scholarly line was founded by Thābit ibn Qurra (836–901), a Harranian scholar and major figure in the Translation Movement. Thābit was an open pagan; his funeral inscription explicitly refers to him as a "Sabian, son of a Sabian."[95] He was a mathematician, astronomer, and translator whose works introduced the theoretical framework for celestial mechanics and the technical basis for talismanic operations into Arabic.[96] His lineage continued through his descendants, including his son Sinān ibn Thābit ibn Qurra (c. 880–943) and grandson Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān ibn Thābit (c. 908–946), who served as elite court physicians and mathematicians.[97]

The foundational corpus of Arabic alchemy is associated with Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Geber) (c. 721–815). The intellectual history surrounding Geber firmly links his esoteric knowledge to the Harranian scholarly network.[98] This connection is rooted in the Sabian tradition of viewing Hermes as the prophet of alchemy.[99] Geber is understood to have served as a conduit for the technical and intellectual currents connected to the Sabian traditions, embedding a Hermetic and Chaldean-influenced cosmology into early Islamic chemical arts.[100] Scholars such as Ibn Waḥshiyya (d. 930s) helped codify and transmit texts rooted in ancient Babylonian–Sabian priesthoods, ensuring the literary survival of magical and alchemical lore for subsequent generations of Arabic scholars.[101]

The Transmission to the Latin West (13th Century)

The established Arabic intellectual heritage, which contained the Sabian cosmological influences, was transmitted directly into the Latin West via the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1194–1250) and his primary translator.

Frederick was a unique patron who explicitly sought Arabic esoteric knowledge during the Sixth Crusade.[102] His host, the Ayyubid ruler al-Kāmil, patronized scholars preserving Harranian-style astral science.[103] Contemporary sources [104] confirm that Frederick requested specific books on astrology, treatises on talismans, and Greek philosophical works preserved in Arabic—the very material in which Harranian scholars specialized.[105] Historians (Burnett, Pingree, Akasoy) concur that Frederick's exposure to this lineage of intellectual knowledge is extremely plausible.[106] This contact was established through meeting scholars associated with the Ayyubid court, rather than through direct contact with the Harranian community itself.[107]

Michael Scot (c. 1175–1232): Frederick II's chief court scholar. His work was the primary literary vector for this transmission into Europe.[108] his writings show clear signs of working within the Arabic Hermetic–astral tradition, a lineage that incorporated elements preserved by the Sabians of Harran;[109] Scot’s corpus reflects a strong indirect link to the Sabian tradition through his translation and use of works by Thābit ibn Qurra and his connection to the intellectual network that produced Picatrix-type material (the Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm), which drew upon Harranian cosmology.[110]

Islam in Arabia

Arab paganism gradually disappeared during Muhammad's era through Islamization.[111][112] The sacred months of the Arab pagans were the 1st, 7th, 11th, and 12th months of the Islamic calendar.[113] After Muhammad had conquered Mecca he set out to convert the pagans.[114][115][116] One of the last military campaigns that Muhammad ordered against the Arab pagans was the Demolition of Dhul Khalasa. It occurred in April and May 632 AD, in 10AH of the Islamic Calendar. Dhul Khalasa is referred to as both an idol and a temple, and it was known by some as the Ka'ba of Yemen, built and worshipped by polytheist tribes.[117][118][119]

Modern history

Early Modern Renaissance

The Ordine Osirideo Egizio claimed direct descent from a colony of Alexandrian priests who, fleeing persecution after the 4th century AD, sought refuge in Naples, preserving ancient pagan liturgies almost intact.[120] Through the Middle Ages (5th–15th centuries) these rites persisted in secret esoteric circles and re-emerged during the Renaissance (14th–17th centuries), later inspiring figures such as Raimondo di Sangro (1710–1771), Prince of Sansevero.[121]

Interest in reviving ancient Roman religious traditions can be traced to the Renaissance, with figures such as Gemistus Pletho and Julius Pomponius Laetus advocating for a revival,[122] when Renaissance magic was practiced as a revival of Greco-Roman magic. Gemistus Plethon, who was from Mistras (near the Mani Peninsula—where paganism had endured until the 12th century) encouraged the Medici, descendants of the Maniot Latriani dynasty, to found the Neoplatonic Academy in Florence, helping to spark the Renaissance. In addition Julius Pomponius Laetus (student of Pletho) established the Roman academy which secretly celebrated the Natale di Roma, a festival linked to the foundation of Rome, and the birthday of Romulus.[123][124] The Academy was dissolved in 1468 when Pope Paul II ordered the arrest and execution of some of the members, Pope Sixtus IV allowed Laetus to open the academy again until the Sack of Rome in 1527.

After the French Revolution, the French lawyer Gabriel André Aucler (mid 1700s–1815) adopted the name Quintus Nautius and sought to revive paganism, styling himself as its leader. He designed religious clothing and performed pagan rites at his home. In 1799, he published La Thréicie, presenting his religious views. His teachings were later analyzed by Gérard de Nerval in Les Illuminés (1852).[125] Admiring ancient Greece and ancient Rome, Aucler supported the French Revolution and saw it as a path to restoring an ancient republic.[126] He took the name Quintus Nautius, claimed Roman priestly lineage, and performed Orphic rites at his home.[127] His followers were mainly his household.[125] In 1799, he published La Thréicie, advocating a revival of paganism in France, condemning Christianity, and promoting universal animation.[128]

In the 17th century, the description of paganism turned from a theological aspect to an ethnological one, and religions began to be understood as part of the ethnic identities of peoples, and the study of the religions of so-called primitive peoples triggered questions as to the ultimate historical origin of religion. Jean Bodin viewed pagan mythology as a distorted version of Christian truths.[129] Nicolas Fabri de Peiresc saw the pagan religions of Africa of his day as relics that were in principle capable of shedding light on the historical paganism of Classical Antiquity.[130]

Late Modern Romanticism

The 19th century saw much scholarly interest in the reconstruction of pagan mythology from folklore or fairy tales. Depictions of reconstructed themes in theater, poetry, and music flourished alongside political invocations of reimagined pagan codes and ethics.

Folklore reconstructions were notably attempted by the Brothers Grimm, especially Jacob Grimm in his Teutonic Mythology, and Elias Lönnrot with the compilation of the Kalevala. The work of the Brothers Grimm influenced other collectors, both inspiring them to collect tales and leading them to similarly believe that the fairy tales of a country were particularly representative of it, to the neglect of cross-cultural influence. Among those influenced were the Russian Alexander Afanasyev, the Norwegians Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, and the Englishman Joseph Jacobs.[131]

Poetic examples display how paganist themes were mobilized in ethical and cultural discourse of the era. G. K. Chesterton wrote: "The pagan set out, with admirable sense, to enjoy himself. By the end of his civilization he had discovered that a man cannot enjoy himself and continue to enjoy anything else."[132] In sharp contrast, the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne would comment on this same theme: "Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy breath; We have drunken of things Lethean, and fed on the fullness of death."[133]

Romanticist interest in non-classical antiquity coincided with the rise of Romantic nationalism and the rise of the nation state in the context of the 1848 revolutions, leading to the creation of national epics and national myths for the various newly formed states. Pagan or folkloric topics were also common in the musical nationalism of the period. Paganism resurfaces as a topic of fascination in 18th to 19th-century Romanticism, in particular in the context of the literary Celtic, Slavic and Viking revivals, which portrayed historical Celtic, Slavic and Germanic polytheists as noble savages.

Great God! I'd rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

— William Wordsworth, "The World Is Too Much with Us", lines 9–14

In Italy

With the fall of the Papal States the process of Italian unification fostered anti-clerical sentiment among the intelligentsia. The Brotherhood of Myriam, founded in 1899, inherited its lineage from the Ordine Osirideo Egizio and can be understood as a form of modern neopaganism that revives and adapts ancient Egyptian and Greco-Egyptian rituals for contemporary spiritual practice.[134][135] Intellectuals like archaeologist Giacomo Boni and writer Roggero Musmeci Ferrari Bravo promoted the restoration of Roman religious practices.[136][137] In 1927, philosopher and esotericist Julius Evola founded the Gruppo di Ur in Rome, along with its journal Ur (1927–1928), involving figures like Arturo Reghini. In 1928, Evola published Imperialismo Pagano, advocating Italian political paganism to oppose the Lateran Pacts. The journal resumed in 1929 as Krur. A mysterious document published in Krur in 1929, attributed to orientalist Leone Caetani, suggested that Italy's World War I victory and the rise of fascism were influenced by Etruscan-Roman rites.[138]

Late 20th century

The 1960s and 1970s saw a resurgence in neo-Druidism as well as the rise of modern Germanic paganism in the United States and in Iceland. In the 1970s, Wicca was notably influenced by feminism, leading to the creation of an eclectic, Goddess-worshipping movement known as Dianic Wicca.[139] The 1979 publication of Margot Adler's Drawing Down the Moon and Starhawk's The Spiral Dance opened a new chapter in public awareness of paganism.[140] With the growth and spread of large, pagan gatherings and festivals in the 1980s, public varieties of Wicca continued to further diversify into additional, eclectic sub-denominations, often heavily influenced by the New Age and counter-culture movements. These open, unstructured or loosely structured traditions contrast with British Traditional Wicca, which emphasizes secrecy and initiatory lineage.[141]

The public appeal for pre-Christian Roman spirituality in the years following fascism was largely driven by Julius Evola. By the late 1960s, a renewed "operational" interest in pagan Roman traditions emerged from youth circles around Evola, particularly concerning the experience of the Gruppo di Ur.[142] Evola's writings incorporated concepts from outside classical Roman religion, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, sexual magic, and private ritual nudity. This period saw the rise of the Gruppo dei Dioscuri in cities like Rome, Naples, and Messina, which published a series of four booklets, including titles such as L'Impeto della vera cultura and Rivoluzione Tradizionale e Sovversione, before fading from public view.[143] The Evolian journal Arthos, founded in Genoa in 1972 by Renato del Ponte, expressed significant interest in Roman religion. In 1984, the Gruppo Arx revived Messina's Dioscuri activities, and Reghini's Pythagorean Association briefly resurfaced in Calabria and Sicily from 1984 to 1988, publishing Yghìeia.

Other publications include the Genoese Il Basilisco (1979–1989), which released several works on pagan studies, and Politica Romana (1994–2004), seen as a high-level Romano-pagan journal. One prominent figure was actor Roberto Corbiletto, who died in a mysterious fire in 1999.The 1980s and 1990s also saw an increasing interest in serious academic research and reconstructionist pagan traditions. The establishment and growth of the Internet in the 1990s brought rapid growth to these, and other pagan movements.[141]

By the time of the collapse of the former Soviet Union in 1991, freedom of religion was legally established across Russia and a number of other newly independent states, allowing for the growth in both Christian and non-Christian religions.[144]

Remove ads

Modern paganism

Summarize

Perspective

21st century

In the 2000s, Associazione Tradizionale Pietas began reconstructing temples across Italy and sought legal recognition from the state, drawing inspiration from similar groups like YSEE in Greece. In 2023, Pietas participated in the ECER meeting, resulting in the signing of the Riga Declaration, which calls for the recognition of European ethnic religions.[145] Public rituals, such as those celebrating the ancient festival of the Natale di Roma, have also resumed in recent years.[146][147][148]

The idea of practicing Roman religion in the modern era has spread beyond Italy, with practitioners found in countries across Europe and the Americas. The most prominent international organization is Nova Roma, founded in 1998, with active groups worldwide.[149]

Modern paganism, or Neopaganism, includes reconstructed practice such as Roman Polytheistic Reconstructionism, Hellenism, Slavic Native Faith, Celtic Reconstructionist Paganism, or heathenry, as well as modern eclectic traditions such as Wicca and its many offshoots, Neo-Druidism, and Discordianism.

However, there often exists a distinction or separation between some polytheistic reconstructionists such as Hellenism and revivalist neopagans like Wiccans. The divide is over numerous issues such as the importance of accurate orthopraxy according to ancient sources available, the use and concept of magic, which calendar to use and which holidays to observe, as well as the use of the term pagan itself.[150][151][152]

In 1717 John Toland became the first Chosen Chief of the Ancient Druid Order, which became known as the British Circle of the Universal Bond.[153] Many of the revivals, Wicca and Neo-Druidism in particular, have their roots in 19th century Romanticism and retain noticeable elements of occultism or Theosophy that were current then, setting them apart from historical rural (paganus) folk religion. Most modern pagans, however, believe in the divine character of the natural world and paganism is often described as an Earth religion.[154]

There are a number of neopagan authors who have examined the relation of the 20th-century movements of polytheistic revival with historical polytheism on one hand and contemporary traditions of folk religion on the other. Isaac Bonewits introduced a terminology to make this distinction.[155]

- Neopaganism

- The overarching contemporary pagan revival movement which focuses on nature-revering, living, pre-Christian religions or other nature-based spiritual paths, and frequently incorporating contemporary liberal values.[citation needed] This definition may include groups such as Wicca, Neo-Druidism, Heathenry, and Slavic Native Faith.

- Paleopaganism

- A retronym coined to contrast with Neopaganism, original polytheistic, nature-centered faiths, such as the pre-Hellenistic Greek and pre-imperial Roman religion, pre-Migration period Germanic paganism as described by Tacitus, or Celtic polytheism as described by Julius Caesar.

- Mesopaganism

- A group, which is, or has been, significantly influenced by monotheistic, dualistic, or nontheistic worldviews, but has been able to maintain an independence of religious practices. This group includes aboriginal Americans as well as Aboriginal Australians, Viking Age Norse paganism and New Age spirituality. Influences include: Spiritualism, and the many Afro-Diasporic faiths like Haitian Vodou, Santería and Espiritu religion. Isaac Bonewits includes British Traditional Wicca in this subdivision.

Prudence Jones and Nigel Pennick in their A History of Pagan Europe (1995) classify pagan religions as characterized by the following traits:

- Polytheism: Pagan religions recognise a plurality of divine beings, which may or may not be considered aspects of an underlying unity (the soft and hard polytheism distinction).

- Nature-based: Some pagan religions have a concept of the divinity of nature, which they view as a manifestation of the divine, not as the fallen creation found in dualistic cosmology.

- Sacred feminine: Some pagan religions recognize the female divine principle, identified as the Goddess (as opposed to individual goddesses) beside or in place of the male divine principle as expressed in the Abrahamic God.[156]

In modern times, Heathen and Heathenry are increasingly used to refer to those branches of modern paganism inspired by the pre-Christian religions of the Germanic, Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon peoples.[157]

In Iceland, the members of Ásatrúarfélagið account for nearly 2% of the total population,[158] therefore being nearly six thousand people. In Lithuania, many people practice Romuva, a revived version of the pre-Christian religion of that country. Lithuania was among the last areas of Europe to be Christianized. Heathenry has been established on a formal basis in Australia since at least the 1930s.[159]

Remove ads

Ethnic religions of pre-Christian Europe

Reconstructionist groups

See also

- Animism

- Anitism

- Crypto-paganism

- Dharmic religions

- East Asian religions

- Eleusinian Mysteries

- Henotheism

- Jungian psychology

- Kemetism

- List of pagans

- List of modern pagan movements

- List of modern pagan temples

- List of religions and spiritual traditions

- Myth and ritual

- Naturalistic pantheism

- Nature worship

- Panentheism

- Polytheism

- Secular paganism

- Sentientism

- Totemism

- Virtuous pagan

- Worship of heavenly bodies

Remove ads

Notes

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads