Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

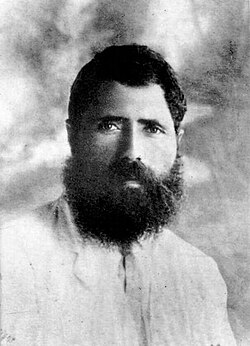

Yosef Haim Brenner

Russian-born Hebrew-language author From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Yosef Haim Brenner (Hebrew: יוסף חיים ברנר, romanized: Yosef Ḥayyim Brener; 11 September 1881 – 2 May 1921) was a Russian-born Hebrew-language author and public intellectual, and one of the pioneers of modern Hebrew literature. His writings, public engagement, and murder during the 1921 Jaffa riots contributed to his enduring status as a symbolic figure in the Yishuv.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

Yosef Haim Brenner was born into a poor Jewish family in Novi Mlyny, then part of the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine). He studied at a yeshiva in Pochep, and published his first story, Pat Leḥem ('A Loaf of Bread') in Ha-Melitz in 1900, followed by a collection of short stories in 1901.[1]

In 1902, Brenner was drafted into the Imperial Russia army. When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904, he deserted his post. He was initially captured, but escaped to London with the help of the General Jewish Labour Bund, a socialist Jewish workers' organization which he had joined as a youth.

While in London, Brenner lived in an apartment in Whitechapel, which doubled as an office for Ha-Me'orer, a Hebrew periodical that he edited and published in 1906–7. In 1905, he befriended the Yiddish writer Lamed Shapiro. Brenner's time in London was later chronicled by Asher Beilin in the 1922 biography Brenner in London.

Life in London and Palestine

Brenner immigrated to Palestine (then part of the Ottoman Empire) in 1909. Motivated by Zionist ideals, he initially worked as a farmer. However, he was unable to endure the physical demands of manual labor and soon transitioned to teaching and writing. Until 1914, he lived in Jerusalem, in a modest room in the Ezrat Yisrael neighbourhood. He was a member of the editorial board of the newspaper Ha-Aḥdut and contributed articles to other newspapers.

He later moved to Tel Aviv, where he taught at the Gymnasia Herzliya high school. During the 1917 Tel Aviv deportation, Brenner relocated to Hadera, returning only after the British mandate began.

Personal life

In 1913, Brenner married kindergarten teacher Chaya Braude. The couple had one son, Uri Nissan, named after his friend Uri Nissan Gnessin, who had died about a year earlier. The marriage did not last long, and his wife left him, taking their son with her to Berlin.[citation needed] According to biographer Anita Shapira, he suffered from depression and problems of sexual identity.[2]

Death and Legacy

Yosef Haim brenner was murdered in Jaffa in May 1921 during the Jaffa riots.

The site of his murder on Kibbutz Galuyot street is now marked by Brenner House, a centre for Hanoar Haoved Vehalomed, the youth organization of the Histadrut. Kibbutz Givat Brenner was also named for him, while kibbutz Revivim was named in honor of his magazine. The Brenner Prize, one of Israel's top literary awards, is named for him.[3]

Remove ads

Views and controvereies

Summarize

Perspective

In his writing, Brenner praised the Zionist endeavour, though also affirmed that the modern Land of Israel was but another Diaspora.[2] Brenner was a lecturer and teacher in the roadwork camps of the Yosef Trumpeldor Labour Battalion and was described as one of the most passionate and inspiring advocates for the unification of the workers' parties in the Land of Israel.[citation needed]

At the end of 1910, Brenner published a provocative article in the newspaper Ha-Poel Ha-Tza'ir, containing a blunt and dismissive rejection of all religions, including Judaism, while expressing allegiance to Jewish culture, which Brenner saw as rooted in both the Tanakh and the New Testament. The article sparked months of debate and public discourse in both the Yishuv and the Diaspora. The "Odessa Committee" withdrew its financial support from the newspaper, and in response, local writers and workers raised funds to ensure the paper's continued existence.[4]

The affair had lasting effects on Brenner's public image and professional life. When he began teaching literature at the Herzliya Gymnasium in 1915, his appointment faced opposition from the school's supervisory board. As a compromise, an instructor was assigned to oversee Brenner's classes to ensure he followed the curriculum and did not incite against religion. Eventually, Brenner's teaching was found to be exemplary, and he continued teaching at the Gymnasium, including Bible, Mishnah, and Hebrew language.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Literary activity

Summarize

Perspective

As a writer, Brenner was a experimental both in his use of language and in literary form. With Modern Hebrew still in its infancy, Brenner improvised with an intriguing mixture of Hebrew, Aramaic, Yiddish, English and Arabic. In his attempt to portray life realistically, his work is full of emotive punctuation and ellipses. Robert Alter, in the collection Modern Hebrew Literature, writes that Brenner "had little patience for the aesthetic dimension of imaginative fictions: 'A single particle of truth,' he once said, 'is more valuable to me than all possible poetry.'" Brenner "wants the brutally depressing facts to speak for themselves, without any authorial intervention or literary heightening."[5]

Brenner played a significant role in advancing modern Hebrew literature and supporting emerging writers. Notably, he introduced S.Y. Agnon to the Jewish literary and cultural public by helping to publish his book And the Crooked Shall Be Made Straight. He translated from Russian into Hebrew Dostoevsky's' Crime and Punishment and Tolstoy's Master and Man, and from German into Hebrew two books by Gerhart Hauptmann as well as The Jews of Today by Arthur Ruppin. He also engaged in translating works of popular science.

From 1919, he edited the literary monthly Ha-Adamah ('The Land'), which was published as an appendix to Kuntres, edited by Berl Katznelson.

Published works

- Me-ʻemek ʻakhor: tsiyurim u-reshimot [Out of a Gloomy Valley]. Warsaw: Tushiyah. 1900. A collection of 6 short stories about Jewish life in the diaspora.

- Ba-ḥoref [In Winter] (novel). Ha-Shilo'aḥ. 1904.

- Yiddish: Warsaw, Literarisher Bleter, 1936.

- Mi-saviv la-nekudah [Around the Point] (novel). Ha-Shilo'aḥ. 1904.

- Yiddish: Berlin, Yiddisher Literarisher Ferlag, 1923.

- Me'ever la-gvulin [Beyond the Border] (play). London: Y. Groditzky. 1907.

- Min ha-metzar [Out of the Depths] (novella). Ha-Olam. 1908–1909.

- Bein mayim le-mayim [Between Water and Water] (novella). Warsaw: Sifrut. 1909.

- Kitve Y. Ḥ. Brenner [Collected Works]. Kruglyiakov. 1909.

- Atzabim [Nerves] (novella). Lvov: Shalekhet. 1910.

- English: In Eight Great Hebrew Short Novels, New York, New American Library, 1983.

- Spanish: In Ocho Obras Maestras de la Narrativa Hebrea, Barcelona, Riopiedras, 1989.

- French: Paris, Intertextes, 1989; Paris, Noel Blandin, 1991.

- Mi-kan u-mi-kan: shesh maḥbarot u-miluʼim [From Here and There] (novel). Warsaw: Sifrut. 1911.

- Sipurim [Stories]. Sifriyah ʻamamit; no. 9. New York: Kadimah. 1917. hdl:2027/uc1.aa0012503777.

- Shekhol ve-khishalon; o, sefer ha-hitlabtut [Breakdown and Bereavement] (novel). Hotsaʼat Shtibel. 1920.

- English: London, Cornell Univ. Press, 1971; Philadelphia, JPS, 1971; London, The Toby Press, 2004.[6]

- Chinese: Hefei, Anhui Literature and Art Publishing House, 1998.

- Kol kitve Y. Ḥ. Brenner [Collected Works of Y. H. Brenner]. Tel Aviv: Hotsaʼat Shtibel. 1924–30.

- Ketavim [Collected Works] (four volumes). Ha-kibutz ha-me’uhad. 1978–85.

- English: Colorado, Westview Press, 1992.

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads