Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

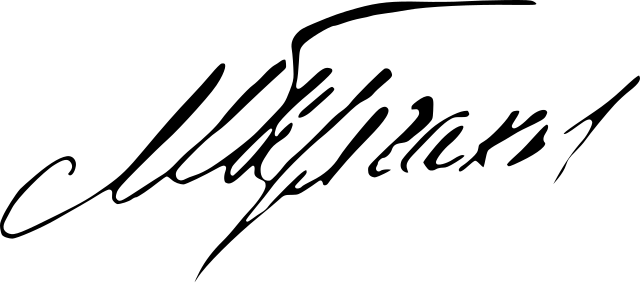

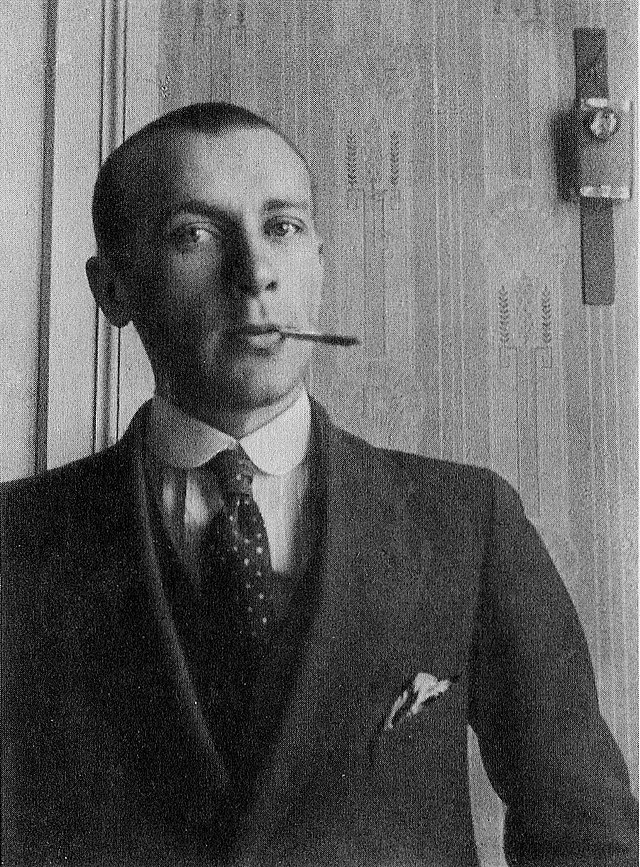

Mikhail Bulgakov

Russian and Soviet author (1891–1940) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov[a] (/bʊlˈɡɑːkɒf/ buul-GAH-kof; Russian: Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil ɐfɐˈnasʲjɪvʲɪdʑ bʊlˈɡakəf] 15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1891 – 10 March 1940) was a Russian and Soviet novelist and playwright. His novel The Master and Margarita,[1] published posthumously, has been called one of the masterpieces of the 20th century.[2] He also wrote the novel The White Guard and the plays Ivan Vasilievich, Flight (also called The Run), and The Days of the Turbins.

Some of his works (Flight, all his works between 1922 and 1926, and others) were banned by the Soviet government, and personally by Joseph Stalin, after it was decided by them that they "glorified emigration and White generals".[3] On the other hand, Stalin loved Bulgakov's dramatization of The White Guard, anodynely renamed The Days of the Turbins. The Soviet leader reportedly attended the play at least 15 times, even calling a theater to personally demand its production after the playwright's fall from favor.[4][5] Despite Stalin's intercession in this and other matters Bulgakov was only briefly successful during his lifetime. After his death, especially once the publication of The Master and Margarita had been accomplished in 1966-67, his work was reassessed. He is now widely regarded as one of the great Russian authors of the 20th century.

Remove ads

Life and work

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

Mikhail Bulgakov was born on 15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1891 in Kiev, Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire, at 28 Vozdvishenskaya Street, into a Russian family, and baptized on 18 May [O.S. 6 May] 1891.[6] He was the oldest of the seven children of Afanasiy Bulgakov – a state councilor, a professor at the Kiev Theological Academy, as well as a prominent Russian Orthodox essayist, thinker and translator of religious texts. His mother was Varvara Mikhailovna Bulgakova (nee Pokrovskaya), a former teacher at a women's gymnasium.[7][8] The academician Nikolai Petrov was his godfather,[9] while his godmother was his paternal grandmother, Olympiada.[10]

Afanasiy Bulgakov (1859 - 1907) was born in Oryol, Oryol Governorate, the oldest son of Ivan Avraamovich Bulgakov, a priest, and his wife Olympiada Ferapontovna.[11][12] He first studied in a seminary in Oryol, and then studied in Kiev Theological Academy from 1881 to 1885, and was named a docent of the Academy in 1886.[13] Varvara Bulgakova (1869 - 1922) was born in Karachev; her father, Mikhail Pokrovsky, was a protoiereus.[11][8] Afanasiy and Varvara married in 1890.[14] Their other children were Vera (b. 1892), Nadezhda (b. 1893), Varvara (b. 1895), Nikolai (b. 1898), Ivan (b. 1900), and Yelena (b. 1902).[15]

All the children received a good education; they read the classics of Russian and European literature, studied music, and went to concerts. Mikhail played piano, sang baritone, and enjoyed opera. In particular, he enjoyed Faust by Gounod; according to his sister Nadezhda, he attended showings of Faust at least 40 times.[16] At home, Mikhail and his siblings acted out plays that they enjoyed; the family also had a dacha in Bucha.[17][18]

In 1900, Bulgakov was enrolled in the Second Kiev Gymasium; in 1901, Bulgakov was enrolled in the First Kiev Gymnasium,[19] where he developed an interest in Russian and European literature (his favourite authors at the time being Gogol, Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Saltykov-Shchedrin, and Dickens), theatre and opera. The teachers of the Gymnasium exerted a great influence on the formation of his literary taste.

In 1906, Afanasy Bulgakov fell ill with malignant nephrosclerosis; he died of the illness in 1907. The loss of his father caused Mikhail to turn away from the Orthodox faith. His sister Nadezhda observed that he showed a great interest in the theories of Darwin, and had turned to "non-belief".[20] After Afanasy's death, Mikhail's mother, a well-educated and extraordinarily diligent person, assumed responsibility for his education.

In the summer of 1908, Bulgakov met Tatyana Lappa. Lappa, who lived in Saratov, had arrived in Kiev to visit her relatives; her aunt was a friend of Varvara Bulgakova and thus introduced her to the young Bulgakov.[21][22] In 1909, Bulgakov began to study medicine at the Kiev University. In 1912, Lappa arrived in Kiev to study. The two married in April 1913.[23]

Bulgakov was staying with Lappa's parents in Saratov at the outbreak of the First World War. Her mother opened a field hospital for wounded soldiers, where Bulgakov worked as a doctor.[24][25][26] The couple returned to Kiev in the autumn.[24] In 1916, Bulgakov graduated from the university, after which he volunteered for the Red Cross.[27] His wife volunteered as a nurse.[25] He first worked in Kamianets-Podilskyi, then he was transferred to Chernivtsi in the same year.[28][29][30] In September of that year he was transferred to Moscow; and then to the village of Nikolskoye in the Smolensk Oblast.[28][26] The time he spent working as a doctor would be the inspiration for his short story cycle, A Young Doctor's Notebook and his short story, Morphine.[31] Morphine is based on the author's actual addiction to morphine, which he started taking to alleviate the allergic effects of an anti-diphtheria drug, after accidentally infecting himself with the disease while treating a child with the same condition. While visiting Kiev with his wife, they received advice from Bulgakov's stepfather on countering his addiction in the form of injecting distilled water instead of morphine, which gradually helped Bulgakov to end his addiction.[32]: 22–25

In the autumn of 1917 he was transferred to the town of Vyazma, but left for Moscow in either November or December of that year in an unsuccessful attempt to gain a military discharge.[33] After briefly visiting Lappa's parents in Saratov, they returned to Kiev in February 1918.[34][35] Upon returning Bulgakov opened a private practice at his home at Andreyevsky Descent, 13.[36] Here he lived through the Civil War and witnessed ten coups. Successive governments drafted the young doctor into their service while two of his brothers were serving in the White Army against the Bolsheviks.

In 1919, he was mobilised as an army physician by the White Army.[37] In September 1919, Bulgakov was in Grozny with his wife.[38] While there, he observed the fighting between the forces of Anton Denikin and Uzun-Hajji in the city of Chechen-Aul; this became part of one of his earliest works, "Unusual Adventures" (Russian: Необыкновенные приключения).[39] There, he became seriously ill with typhus, and was bedridden for several weeks.[40][30] Around this time, both his brothers Nikolai and Ivan emigrated. The family lost contact with them, and Bulgakov never saw his brothers again.[40]

Career

Bulgakov had expressed his desire to be a writer as early as 1912 or 1913, when he showed his sister Nadezhda his first attempt at a story, called The Fiery Serpent (Russian: Огненный змий), about an alcoholic who dies in a fit of delirium tremens, and stated to her that he planned to be a writer.[41][42] According to his first wife, he first began to consistently write in Vyazma, where at night he would work on a story called The Green Serpent (Russian: Зеленый змий).[42]

After his illness, Bulgakov abandoned his medical practice to pursue writing. Bulgakov in his autobiography wrote that he abandoned medicine for writing in early 1920; according to his friend Pavel Popov, Bulgakov abandoned medicine for good on 15 February 1920. At this time, he was in Vladikavkaz.[43] His first book was an almanac of feuilletons called Future Perspectives, written and published the same year.

Bulgakov considered emigration; he made his way to the city of Batum in 1921 to attempt to emigrate. His attempts failed; he then decided to move to Moscow and attempt a career as a writer.[44] He arrived in Moscow in September 1921; his wife had arrived three weeks prior.[45] He was appointed secretary to the literary section of Glavpolitprosvet, where he worked until November, when the literary section closed. He began work on a novel there, which ultimately turned into his story Morphine. The story was published only once in his lifetime - in 1927.[46] To make a living, he started working as a feuilleton writer for the newspapers Gudok and Nakanune. His work Diaboliad was written in 1923.[47]

The death of Bulgakov's mother from typhus on 1 February 1922 influenced the writing of The White Guard. He completed the novel in 1924.[48][49] Early in 1924, Bulgakov attended a party hosted by Aleksey Tolstoy, where he met Lyubov Belozerskaya. The same year, Bulgakov divorced Tatyana Lappa. In April of the next year, he married Belozerskaya. The White Guard began serialization in 1925; he dedicated the work to Belozerskaya.[50][51]

The White Guard caught the attention of the Moscow Art Theatre. Bulgakov was invited in April 1925 to turn his work into a play, to be staged at the theater. The play was staged under the name The Days of the Turbins in October 1926, and met with success. Also in 1925 Bulgakov was approached by the Vakhtangov Theatre to write a play for them based on The White Guard. Bulgakov offered to write them another play. The resulting play, Zoyka's Apartment, was also staged in October 1926, and a third play, The Crimson Island, was staged at the Kamerny Theatre in December 1928.[52][53] His plays were popular with viewers, but attracted negative reviews from critics.[54]

Bulgakov began work on the play Flight in 1926, and completed it in 1928. He had planned to stage it at the Moscow Art Theatre. Glavrepertkom, the government organ responsible for censoring and approving theatrical works, published a resolution on 9 May, stating that the play had been written to glorify emigration and White Army generals, and therefore, it was banned. Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, wanting to save the play, invited Maxim Gorky, several theater critics and several members of Glaviskusstvo (Central Arts Administration) and Glavrepertkom to a reading of Flight on 9 October. Gorky, as well as most of those attending, was impressed by the play. Nemirovich-Danchenko began rehearsals the next day, with Nikolai Khmelyov, Viktor Stanitsyn, Alla Tarasova and Mark Prudkin in the main roles. However, Glavrepertkom showed Flight to Joseph Stalin, who agreed with the committee that it should be banned. Flight would only be staged again in 1957, 17 years after Bulgakov's death.[55]

On 6 December 1929, Bulgakov completed his play The Cabal of Hypocrites. However, the play was banned by Glavrepertkom on 18 March 1930. In despair, Bulgakov wrote personally to Joseph Stalin, requesting aid. He received a phone call directly from Stalin on 18 April, who asked him whether he really desired to leave the Soviet Union. Bulgakov replied that he did not want to leave his homeland. Stalin told him to apply for work as a director at the Moscow Art Theatre. In May 1930, he became a director at the MAT, and The Cabal of Hypocrites was permitted in October 1931 by Glavrepertkom to be staged, under the title of Molière.[56] Bulgakov began work on an adaptation of Gogol's Dead Souls for the stage that month. The play was complete by 1932. As with his earlier plays, it received a positive reaction among general viewers, and a negative reaction with critics.[57]

In 1929, Bulgakov met Elena Shilovskaya. The two married in October 1932. Elena's younger son from her previous marriage, Sergey, came to live with them.[58] During the last decade of his life, Bulgakov continued to work on The Master and Margarita, wrote plays, critical works, and stories and made several translations and dramatisations of novels. Many of them were not published, others were "torn to pieces" by critics. Much of his work (ridiculing the Soviet system) stayed in his desk drawer for several decades.

Last years

Bulgakov began work on The Master and Margarita in either 1928 or 1929. He burnt the first draft in 1930. The first version of the novel was very different from the final version: there was no Master or Margarita, and the novel was called "The Engineer's Hoof" (Russian: Копыто инженера, romanized: Kopyto inzhenera).[59]

In the late 1930s, he joined the Bolshoi Theatre as a librettist and consultant. He left after perceiving that none of his works would be produced there. Stalin's favor protected Bulgakov from arrests and execution, but he could not get his writing published. When his last play Batum (1939), a complimentary portrayal of Stalin's early revolutionary days,[60] was banned before rehearsals, Bulgakov requested permission to leave the country but was refused.

In poor health, Bulgakov devoted his last years to what he called his "sunset" novel. The years 1937 to 1939 were stressful for Bulgakov, veering from glimpses of optimism, believing the publication of his masterpiece could still be possible, to bouts of depression, when he felt as if there were no hope. On 15 June 1938, when the manuscript was nearly finished, Bulgakov wrote in a letter to his wife:

"In front of me 327 pages of the manuscript (about 22 chapters). The most important remains – editing, and it's going to be hard, I will have to pay close attention to details. Maybe even re-write some things... 'What's its future?' you ask? I don't know. Possibly, you will store the manuscript in one of the drawers, next to my 'killed' plays, and occasionally it will be in your thoughts. Then again, you don't know the future. My own judgement of the book is already made and I think it truly deserves being hidden away in the darkness of some chest..."

In 1939, Bulgakov organized a private reading of The Master and Margarita to his close circle of friends. Elena Bulgakova remembered 30 years later, "When he finally finished reading that night, he said: 'Well, tomorrow I am taking the novel to the publisher!' and everyone was silent", "...Everyone sat paralyzed. Everything scared them. P. (P. A. Markov, in charge of the literature division of MAT) later at the door fearfully tried to explain to me that trying to publish the novel would cause terrible things", she wrote in her diary (14 May 1939).

In the last month of his life, friends and relatives were constantly on duty at his bedside. On 10 March 1940, Bulgakov died from nephrotic syndrome[61] (an inherited kidney disorder). His father had died of the same disease, and from his youth Bulgakov had guessed his future mortal diagnosis. On 11 March, a civil funeral was held in the building of the Union of Soviet Writers. Before the funeral, the Moscow sculptor Sergey Merkurov cast a death mask of his face. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Remove ads

Works

Summarize

Perspective

During his life, Bulgakov was best known for the plays he contributed to Konstantin Stanislavski's and Nemirovich-Danchenko's Moscow Art Theatre. Stalin was known to be fond of the play Days of the Turbins (Дни Турбиных, 1926), which was based on Bulgakov's novel The White Guard. Even after his plays were banned from the theatres, Bulgakov wrote a comedy about Ivan the Terrible's visit into 1930s Moscow. His play Batum (Батум, 1939) about the early years of Stalin was prohibited by the premier himself. Bulgakov later reflected his experience of being a Soviet playwright in Theatrical Novel (Театральный роман, 1936, unfinished).

His prose remained unprinted from the late 1920s to 1961; his plays likewise remained mostly unstaged - only in 1954 would his play Day of the Turbins be staged again at the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Theatre.[62] In 1962, his Life of Monsieur de Molière was published; in 1963, Notes of a Young Doctor; in 1965, Theatrical Novel and a collection of his plays, including Flight, Ivan Vasilievich, and The Cabal of Hypocrites were published; in 1966, a collection of his prose including The White Guard; and in 1967 The Master and Margarita was published.[63][64]

Bulgakov began writing novels with The White Guard (Белая гвардия) (1923, partly published in 1925, first full edition 1927–1929, Paris) – a novel about a life of a White Army officer's family in civil war Kiev. In the mid-1920s, he came to admire the works of Alexander Belyaev and H. G. Wells and wrote several stories and novellas with elements of science fiction, notably The Fatal Eggs (Роковые яйца) (1924) and Heart of a Dog (Собачье сердце) (1925). He intended to compile his stories of the mid-twenties (published mostly in medical journals) that were based on his work as a country doctor in 1916–1918 into a collection titled Notes of a Young Doctor (Записки юного врача), but the book came out only in 1963.[65]

The Fatal Eggs tells of the events of a Professor Persikov, who, in experimentation with eggs, discovers a red ray that accelerates growth in living organisms. At the time, an illness passes through the chickens of Moscow, killing most of them, and to remedy the situation, the Soviet government puts the ray into use at a farm. Due to a mix-up in egg shipments, the Professor ends up with chicken eggs, while the government-run farm receives the shipment of ostrich, snake and crocodile eggs ordered by the Professor. The mistake is not discovered until the eggs produce giant monstrosities that wreak havoc in the suburbs of Moscow and kill most of the workers on the farm. The propaganda machine turns on Persikov, distorting his nature in the same way his "innocent" tampering created the monsters. This tale of a bungling government earned Bulgakov his label of counter-revolutionary.

Heart of a Dog features a professor who implants human testicles and a pituitary gland into a dog named Sharik (means "Little Balloon" or "Little Ball" – a popular Russian nickname for a male dog). The dog becomes more and more human as time passes, resulting in all manner of chaos. The tale can be read as a critical satire of liberal nihilism and the communist mentality. It contains a few bold hints to the communist leadership; e.g. the name of the drunkard donor of the human organ implants is Chugunkin[b] which can be seen as a parody on the name of Stalin ("stal'" is steel). It was adapted as a comic opera called The Murder of Comrade Sharik by William Bergsma in 1973. In 1988, an award-winning film version Sobachye Serdtse was produced by Lenfilm, starring Yevgeniy Yevstigneyev, Roman Kartsev and Vladimir Tolokonnikov.

Remove ads

The Master and Margarita

Summarize

Perspective

The novel The Master and Margarita is a critique of Soviet society and its literary establishment. The work is appreciated for its philosophical undertones and for its high artistic level, thanks to its picturesque descriptions (especially of old Jerusalem), lyrical fragments and style. It is a frame narrative involving two characteristically related time periods, or plot lines: a retelling in Bulgakov's interpretation of the New Testament and a description of contemporary Moscow.

The novel begins with Satan visiting Moscow in the 1930s, joining a conversation between a critic and a poet debating the most effective method of denying the existence of Jesus Christ. It develops into an all-embracing indictment of the corruption of communism and Soviet Russia. A story within the story portrays the interrogation of Jesus Christ by Pontius Pilate and the Crucifixion.

It became the best known novel by Bulgakov. He began writing it in 1928, but the novel was finally published by his widow only in 1966, twenty-six years after his death. The book contributed a number of sayings to the Russian language, for example, "Manuscripts don't burn" and "second-grade freshness". A destroyed manuscript of the Master is an important element of the plot. Bulgakov had to rewrite the novel from memory after he burned the draft manuscript in 1930, as he could not see a future as a writer in the Soviet Union at a time of widespread political repression.

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Exhibitions and museums

- Several displays at the One Street Museum are dedicated to Bulgakov's family. Among the items presented in the museum are original photos of Mikhail Bulgakov, books and his personal belongings, and a window frame from the house where he lived. The museum also keeps scientific works of Prof. Afanasiy Bulgakov, Mikhail's father.

Mikhail Bulgakov Museum, Kyiv

The Mikhail Bulgakov Museum (Bulgakov House) in Kyiv has been converted to a literary museum with some rooms devoted to the writer, as well as some to his works.[66] This was his family home, the model for the house of the Turbin family in his play The Days of the Turbins.

The Bulgakov Museums in Moscow

In Moscow, two museums honour the memory of Mikhail Bulgakov and The Master and Margarita. Both are situated in Bulgakov's old apartment building on Bolshaya Sadovaya street nr. 10, in which parts of The Master and Margarita are set. Since the 1980s, the building has become a gathering spot for Bulgakov's fans, as well as Moscow-based Satanist groups, and had various kinds of graffiti scrawled on the walls. The numerous paintings, quips, and drawings were completely whitewashed in 2003. Previously the best drawings were kept as the walls were repainted, so that several layers of different colored paints could be seen around the best drawings.[67]

The Bulgakov House

The Bulgakov House (Russian: Музей – театр "Булгаковский Дом") is situated at the ground floor. This museum has been established as a private initiative on 15 May 2004.

The Bulgakov House contains personal belongings, photos, and several exhibitions related to Bulgakov's life and his different works. Various poetic and literary events are often held, and excursions to Bulgakov's Moscow are organised, some of which are animated with living characters of The Master and Margarita. The Bulgakov House also runs the Theatre M.A. Bulgakov with 126 seats, and the Café 302-bis.

The Museum M.A. Bulgakov

In the same building, in apartment number 50 on the fourth floor, is a second museum that keeps alive the memory of Bulgakov, the Museum M.A. Bulgakov (Russian: Музей М. А. Булгаков). This second museum is a government initiative, and was founded on 26 March 2007.

The Museum M.A. Bulgakov contains personal belongings, photos, and several exhibitions related to Bulgakov's life and his different works. Various poetic and literary events are often held.

Other places named after him

- A minor planet, 3469 Bulgakov, discovered by the Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina in 1982, is named after him.[68]

Works inspired by him

Literature

- Salman Rushdie said that The Master and Margarita was an inspiration for his novel The Satanic Verses (1988).[69]

- John Hodge's play Collaborators (2011) is a fictionalized account of the relationship between Bulgakov and Joseph Stalin, inspired by The Days of the Turbins and The White Guard.

Music

- According to Mick Jagger, Master and Margarita was part of the inspiration for The Rolling Stones' "Sympathy for the Devil" (1968).[70]

- The lyrics of Pearl Jam's song "Pilate", featured on their album Yield (1998), were inspired by Master and Margarita.[71] The lyrics were written by the band's bassist Jeff Ament.

- Alex Kapranos from Franz Ferdinand based "Love and Destroy" on the same book.

Film

- The Flight (1970) — a two-part historical drama based on Bulgakov's Flight, The White Guard and Black Sea. It was the first Soviet adaptation of Bulgakov's writings directed by Aleksandr Alov and Vladimir Naumov, with Bulgakov's third wife Elena Bulgakova credited as a "literary consultant". The film was officially selected for the 1971 Cannes Film Festival.

- The Master and Margaret (1972) — a joint Yugoslav-Italian drama directed by Aleksandar Petrović, the first adaptation of the novel of the same name, along with Pilate and Others. It was selected as the Yugoslav entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 45th Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.

- Pilate and Others (1972) — a German TV drama directed by Andrzej Wajda, it was also a loose adaptation of The Master and Margarita novel. The film focused on the biblical part of the story, and the action was moved to the modern-day Frankfurt.

- Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the Future (1973) — an adaptation of Bulgakov's science fiction/comedy play Ivan Vasilievich about an unexpected visit of Ivan the Terrible to the modern-day Moscow. It was directed by one of the leading Soviet comedy directors Leonid Gaidai. With 60.7 million viewers on the year of release it became the 17th most popular film ever produced in the USSR.[72]

- Dog's Heart (1976) — a joint Italian-German science fiction/comedy film directed by Alberto Lattuada. It was the first adaptation of the Heart of a Dog satirical novel about an old scientist who tries to grow a man out of a dog.

- The Days of the Turbins (1976) — a three-part Soviet TV drama directed by Vladimir Basov. It was an adaptation of the play of the same name which, at the same time, was Bulgakov's stage adaptation of The White Guard novel.

- Heart of a Dog (1988) — a Soviet black-and-white TV film directed by Vladimir Bortko, the second adaptation of the novel of the same name. Unlike the previous version, this film follows the original text closely, while also introducing characters, themes and dialogues featured in other Bulgakov's writings.

- The Master and Margarita (1989) — a Polish TV drama in four parts directed by Maciej Wojtyszko. It was noted by critics as a very faithful adaptation of the original novel.

- After the Revolution (1990) – a feature-length film created by András Szirtes, a Hungarian filmmaker, using a simple video camera, from 1987 to 1989. It is a very loose adaptation, but for all that, it is explicitly based on Bulgakov's novel, in a thoroughly experimental way. What you see in this film is documentary-like scenes shot in Moscow and Budapest, and New York, and these scenes are linked to the novel by some explicit links, and by these, the film goes beyond the level of being but a visual documentary which would only have reminded the viewer of The Master and Margarita.

- Incident in Judaea, a 1991 film by Paul Bryers for Channel 4, focussing on the biblical parts of The Master and Margarita.

- The Master and Margarita (1994) — Russian film directed by Yuri Kara in 1994 and released to public only in 2011. Known for a long, troubled post-production due to the director's resistance to cut about 80 minutes of the film on the producers' request, as well as copyright claims from the descendants of Elena Bulgakova (Shilovskaya).

- The Master and Margarita (2005) — Russian TV mini-series directed by Vladimir Bortko and his second adaptation of Bulgakov's writings. Screened for Russia-1, it was seen by 40 million viewers on its initial release, becoming the most popular Russian TV series.[73]

- Morphine (2008) — Russian film directed by Aleksei Balabanov loosely based on Bulgakov's autobiographical short stories Morphine and A Country Doctor's Notebook. The screenplay was written by Balabanov's friend and regular collaborator Sergei Bodrov, Jr. before his tragic death in 2002.

- The White Guard (2012) — Russian TV mini-series produced by Russia-1. The film was shot in Saint Petersburg and Kyiv and released to mostly negative reviews. In 2014 the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture banned the distribution of the film, claiming that it shows "contempt for the Ukrainian language, people and state".[74]

- A Young Doctor's Notebook (2012–2013) — British mini-series produced by BBC, with Jon Hamm and Daniel Radcliffe playing main parts. Unlike the Morphine film by Aleksei Balabanov that mixed drama and thriller, this version of A Country Doctor's Notebook was made as a black comedy.

- The Master and Margarita. (2024) − Film directed by Michael Lockshin.[1]

Remove ads

Medical eponym

After graduating from the Medical School in 1909, he spent the early days of his career as a venereologist, rather than pursuing his goal of being a pediatrician, as syphilis was highly prevalent during those times. It was during those early years that he described the symptoms and characteristics of syphilis affecting the bones. He described the abnormal and concomitant change of the outline of the crests of the shin-bones with a pathological worm-eaten like appearance and creation of abnormal osteophytes in the bones of those suffering from later stages of syphilis. This became known as "Bulgakov's Sign" and is commonly used in the former Soviet states, but is known as the "Bandy Legs Sign" in the west.[75][76]

Remove ads

Bibliography

Novels

- The White Guard (1925/1975)

- The Master and Margarita (1940/1967)

- Theatrical Novel (1936/1967, aka Black Snow)

Novellas and short stories

- Notes on the Cuffs (1923)

- Diaboliad (1924)

- The Fatal Eggs (1925)

- A Young Doctor's Notebook (1926/1963)

- Heart of a Dog (1925/1968)

- "Morphine" (1927)

- "The Murderer" (1928)

- Great Soviet Short Stories (1962)

- The Terrible News: Russian Stories from the Years Following the Revolution (1990)

- Diaboliad and Other Stories (1990)

- Notes on the Cuff & Other Stories (1991)

- The Fatal Eggs and Other Soviet Satire, 1918–1963 (1993)

Theatre

- Zoyka's Apartment (1925)

- The Days of the Turbins (1926)

- Flight (1927)

- The Cabal of Hypocrites (1929)

- Adam and Eve (1931)

- Alexander Pushkin (The Last Days) (1935)

- Ivan Vasilievich (1936)

Biography

- Life of M. de Molière, 1962

Remove ads

Notes

- In this name that follows East Slavic naming customs, the patronymic is Afanasyevich and the family name is Bulgakov.

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads