Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Georgian language

Official language of the country of Georgia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Georgian (ქართული ენა, kartuli ena, pronounced [ˈkʰäɾt̪ʰuli ˈe̞n̪ä]) is the most widely spoken Kartvelian language. It is the official language of Georgia and the native or primary language of 88% of its population.[2] It also serves as the literary language or lingua franca for speakers of related languages.[3] Its speakers today amount to approximately 3.8 million. Georgian is written with its own unique Georgian scripts, alphabetical systems of unclear origin.[1]

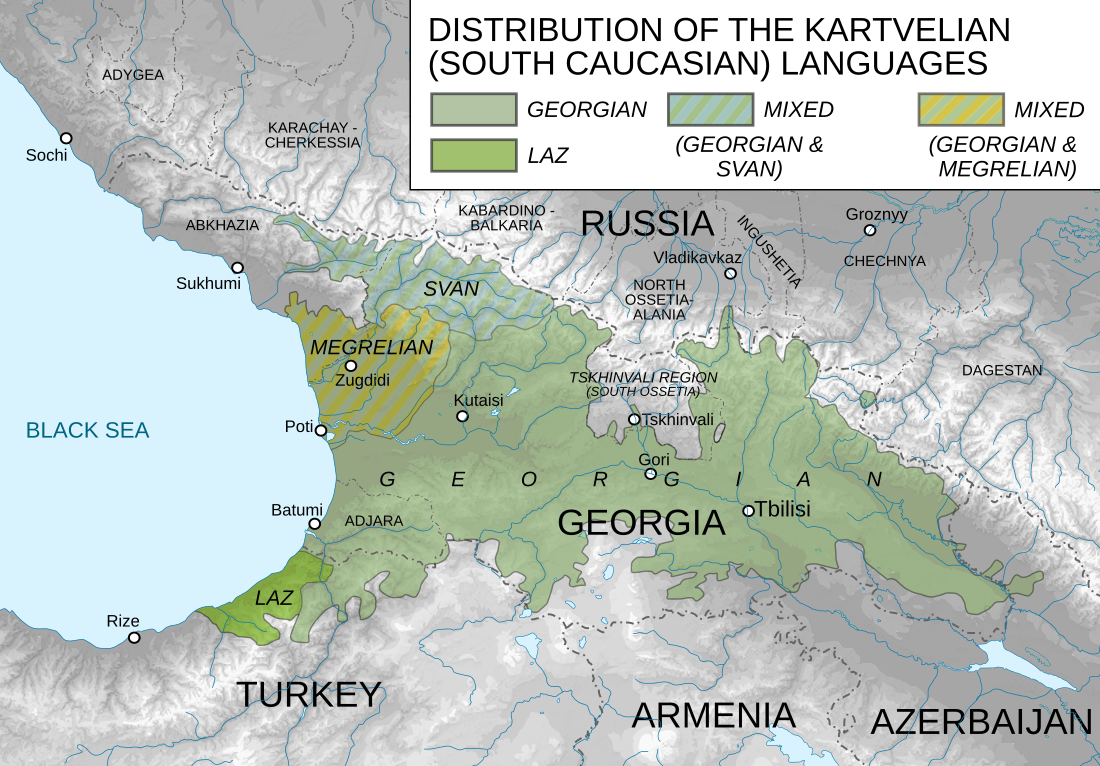

Georgian is most closely related to the Zan languages (Megrelian and Laz) and more distantly to Svan. Georgian has various dialects, with standard Georgian based on the Kartlian dialect, and all dialects are mutually intelligible. The history of Georgian spans from Early Old Georgian in the 5th century, to Modern Georgian today. Its development as a written language began with the Christianization of Georgia in the 4th century.

Georgian phonology features a rich consonant system, including aspirated, voiced, and ejective stops, affricates, and fricatives. Its vowel system consists of five vowels with varying realizations. Georgian prosody involves weak stress, with disagreements among linguists on its placement. The language's phonotactics include complex consonant clusters and harmonic clusters. The Mkhedruli script, dominant in modern usage, corresponds closely to Georgian phonemes and has no case distinction, though it employs a capital-like effect called Mtavruli for titles and inscriptions. Georgian is an agglutinative language with a complex verb structure that can include up to eight morphemes, exhibiting polypersonalism. The language has seven noun cases and employs a left-branching structure with adjectives preceding nouns and postpositions instead of prepositions. Georgian lacks grammatical gender and articles, with definite meanings established through context. Georgian's rich derivation system allows for extensive noun and verb formation from roots, with many words featuring initial consonant clusters.

The Georgian writing system has evolved from ancient scripts to the current Mkhedruli, used for most purposes. The language has a robust grammatical framework with unique features such as syncope in morphophonology and a left-branching syntax. Georgian's vocabulary is highly derivational, allowing for diverse word formations, while its numeric system is vigesimal, based on 20, as opposed to a Base 10 (decimal) system.

Remove ads

Classification

No claimed genetic links between the Kartvelian languages and any other language family in the world are accepted in mainstream linguistics. Among the Kartvelian languages, Georgian is most closely related to the so-called Zan languages (Megrelian and Laz); glottochronological studies indicate that it split from the latter approximately 2700 years ago. Svan is a more distant relative that split off much earlier, perhaps 4000 years ago.[4]

Remove ads

Dialects

The Georgian language has at least 18 dialects, with Standard Georgian being largely based on the Kartlian dialect.[5] Over the centuries, it has exerted a strong influence on the other dialects. As a result, they are all, generally, mutually intelligible with standard Georgian, and with one another.[6]

History

Summarize

Perspective

The history of the Georgian language is conventionally divided into the following phases:[7]

- Early Old Georgian: 5th–8th centuries

- Classical Old Georgian: 9th–11th centuries

- Middle Georgian: 11th/12th–17th/18th centuries

- Modern Georgian: 17th/18th century–present

The earliest extant references to Georgian are found in the writings of Marcus Cornelius Fronto, a Roman grammarian from the 2nd century AD.[8] The first direct attestations of the language are inscriptions and palimpsests dating to the 5th century, and the oldest surviving literary work is the 5th century Martyrdom of the Holy Queen Shushanik by Iakob Tsurtaveli.

The emergence of Georgian as a written language appears to have been the result of the Christianization of Georgia in the mid-4th century, which led to the replacement of Aramaic as the literary language.[7]

By the 11th century, Old Georgian had developed into Middle Georgian. The most famous work of this period is the epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin, written by Shota Rustaveli in the 12th century.

In 1629, a certain Nikoloz Cholokashvili authored the first printed books written (partially) in Georgian, the Alphabetum Ibericum sive Georgianum cum Oratione and the Dittionario giorgiano e italiano. These were meant to help western Catholic missionaries learn Georgian for evangelical purposes.[9]

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

Consonants

On the left are IPA symbols, and on the right are the corresponding letters of the modern Georgian alphabet, which is essentially phonemic.

- Opinions differ on the aspiration of /t͡sʰ, t͡ʃʰ/, as it is non-contrastive.[12]

- Opinions differ on how to classify /x/ and /ɣ/; Aronson (1990) classifies them as post-velar, Hewitt (1995) argues that they range from velar to uvular according to context.

- The uvular ejective stop is commonly realized as a uvular ejective fricative [χʼ] but it can also be [qʼ], [ʔ], or [qχʼ], they are in free variation.[13]

- /r/ is realized as an alveolar tap [ɾ] [14] though [r] occurs in free variation.

- /l/ is pronounced as a velarized [ɫ] before back vowels; it is pronounced as [l] in the environment of front vowels.[15]

- /v/ is realized in most contexts as a bilabial fricative [β] or [v],[16][14] but has the following allophones.[14]

- before voiceless consonants, it is realized as [f] or [ɸ].

- after voiceless consonants it is also voiceless and has been interpreted either as labialization of the preceding consonant [ʷ] or simply as [ɸ].

- whether it is realized as labialization after voiced consonants is debated.

- word-initially before the vowel /u/ and sometimes before other consonants it may be deleted entirely.

- In initial positions, /b, d, ɡ/ are pronounced as a weakly voiced [b̥, d̥, ɡ̊].[17]

- In word-final positions, /b, d, ɡ/ may be devoiced and aspirated to [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ].[17][16]

- /r/ may be dropped in CrC contexts in colloquial speech.[18]

- Word-final /b, d, ɡ/ may be realized as unreleased stops [b̚, d̚, ɡ̚] before another obstruent at word boundaries.[19]

Former /qʰ/ (ჴ) has merged with /x/ (ხ), leaving only the latter.

The glottalization of the ejectives is rather light, and in fact Georgian transliterates the tenuis stops in foreign words and names with the ejectives.[20]

The coronal occlusives (/tʰ tʼ d n/, not necessarily affricates) are variously described as apical dental, laminal alveolar, and "dental".[10]

Vowels

Per Canepari, the main realizations of the vowels are [i], [e̞], [ä], [o̞], [u].[25]

Aronson describes their realizations as [i̞], [e̞], [ä] (but "slightly fronted"), [o̞], [u̞].[24]

Shosted transcribed one speaker's pronunciation more-or-less consistently with [i], [ɛ], [ɑ], [ɔ], [u].[26]

Allophonically, [ə] may be inserted to break up consonant clusters, as in /dɡas/ [dəɡäs].[27]

In casual speech, /i/ preceded or followed by a vowel may be realized as [i̯]~[j].[28][29] similarly, /u/ and /o/ before a vowel may be realized as [w].[29]

Phrase-final unstressed vowels are sometimes partially reduced.[19]

Sequences /aa ii ee oo uu/ occurring at word and morpheme boundaries may be realized as single long vowels [äː iː e̞ː o̞ː uː],[19][30] as in /kʼibeebi/ [ˈkʼibe̞ːbi] ("stairs").[31]

Prosody

Prosody in Georgian involves stress, intonation, and rhythm. Stress is very weak, and linguists disagree as to where stress occurs in words.[24] Jun, Vicenik, and Lofstedt have proposed that Georgian stress and intonation are the result of pitch accents on the first syllable of a word and near the end of a phrase.[32]

According to Borise,[33] Georgian has fixed initial word-level stress cued primarily by greater syllable duration and intensity of the initial syllable of a word.[34] Georgian vowels in non-initial syllables are pronounced with a shorter duration compared to vowels in initial syllables.[35] long polysyllabic words may have a secondary stress on their third or fourth syllable.[36][37][38]

According to Gamq'relidze et al, quadrisyllabic words may be exceptionally stressed on their second syllable.[37] Stressed vowels in Georgian have slightly longer duration, more intensity, and higher pitch compared to unstressed vowels.[37]

Some Georgian dialects have distinctive stress.[39]

Phonotactics

Georgian contains many "harmonic clusters" involving two consonants of a similar type (voiced, aspirated, or ejective) that are pronounced with only a single release; e.g. ბგერა bgera 'sound', ცხოვრება tskhovreba 'life', and წყალი ts’q’ali 'water'.[40] There are also frequent consonant clusters, sometimes involving more than six consonants in a row, as may be seen in words like გვფრცქვნი gvprtskvni 'you peel us' and მწვრთნელი mts’vrtneli 'trainer'.

Vicenik has observed that Georgian vowels following ejective stops have creaky voice and suggests this may be one cue distinguishing ejectives from their aspirated and voiced counterparts.[41]

Remove ads

Writing system

Summarize

Perspective

A commemorative plaque using Mkhedruli for the upper four lines and Mtavruli for the lower two (the name of the person), with each line written in a different typeface

Georgian has been written in a variety of scripts over its history. Currently the Mkhedruli script is almost completely dominant; the others are used mostly in religious documents and architecture.

Mkhedruli has 33 letters in common use; a half dozen more are obsolete in Georgian, though still used in other alphabets, like Mingrelian, Laz, and Svan. The letters of Mkhedruli correspond closely to the phonemes of the Georgian language.

According to the traditional account written down by Leonti Mroveli in the 11th century, the first Georgian script was created by the first ruler of the Kingdom of Iberia, Pharnavaz, in the 3rd century BC. The first examples of a Georgian script date from the 5th century AD. There are now three Georgian scripts, called Asomtavruli 'capitals', Nuskhuri 'small letters', and Mkhedruli. The first two are used together as upper and lower case in the writings of the Georgian Orthodox Church and together are called Khutsuri 'priest alphabet'.

In Mkhedruli, there is no case. Sometimes, however, a capital-like effect, called Mtavruli ('title' or 'heading'), is achieved by modifying the letters so that their vertical sizes are identical and they rest on the baseline with no descenders. These capital-like letters are often used in page headings, chapter titles, monumental inscriptions, and the like.

Keyboard layout

This is the Georgian standard[42] keyboard layout. The standard Windows keyboard is essentially that of manual typewriters.

| “ „ |

1 ! |

2 ? |

3 № |

4 § |

5 % |

6 : |

7 . |

8 ; |

9 , |

0 / |

- _ |

+ = |

← Backspace |

| Tab key | ღ | ჯ | უ | კ | ე ჱ | ნ | გ | შ | წ | ზ | ხ ჴ | ც | ) ( |

| Caps lock | ფ ჶ | ძ | ვ ჳ | თ | ა | პ | რ | ო | ლ | დ | ჟ | Enter key ↵ |

| Shift key ↑ |

ჭ | ჩ | ყ | ს | მ | ი ჲ | ტ | ქ | ბ | ჰ ჵ | Shift key ↑ |

| Control key | Win key | Alt key | Space bar | AltGr key | Win key | Menu key | Control key | |

Remove ads

Grammar

Summarize

Perspective

Morphology

Georgian is an agglutinative language. Certain prefixes and suffixes can be joined in order to build a verb. In some cases, one verb can have up to eight different morphemes in it at the same time. An example is ageshenebinat ('you [all] should've built [it]'). The verb can be broken down to parts: a-g-e-shen-eb-in-a-t. Each morpheme here contributes to the meaning of the verb tense or the person who has performed the verb. The verb conjugation also exhibits polypersonalism; a verb may potentially include morphemes representing both the subject and the object.

Morphophonology

In Georgian morphophonology, syncope is a common phenomenon. When a suffix (especially the plural suffix -eb-) is attached to a word that has either of the vowels a or e in the last syllable, this vowel is, in most words, lost. For example, megobari means 'friend'; megobrebi (megobØrebi) means 'friends', with the loss of a in the last syllable of the word stem.

Inflection

Georgian has seven noun cases: nominative, ergative, dative, genitive, instrumental, adverbial and vocative. An interesting feature of Georgian is that, while the subject of a sentence is generally in the nominative case and the object is in the accusative case (or dative), one can find this reversed in many situations (this depends mainly on the character of the verb). This is called the dative construction. In the past tense of the transitive verbs, and in the present tense of the verb "to know", the subject is in the ergative case.

Syntax

- Georgian is a left-branching language, in which adjectives precede nouns, possessors precede possessions, objects normally precede verbs, and postpositions are used instead of prepositions.

- Each postposition (whether a suffix or a separate word) requires the modified noun to be in a specific case. This is similar to the way prepositions govern specific cases in many Indo-European languages such as German, Latin, or Russian.

- Georgian is a pro-drop language; both subject and object pronouns are frequently omitted except for emphasis or to resolve ambiguity.

- A study by Skopeteas et al. concluded that Georgian word order tends to place the focus of a sentence immediately before the verb, and the topic before the focus. A subject–object–verb (SOV) word order is common in idiomatic expressions and when the focus of a sentence is on the object. A subject–verb–object (SVO) word order is common when the focus is on the subject, or in longer sentences. Object-initial word orders (OSV or OVS) are also possible, but less common. Verb-initial word orders including both subject and object (VSO or VOS) are extremely rare.[43]

- Georgian has no grammatical gender; even the pronouns are ungendered.

- Georgian has no articles. Therefore, for example, "guest", "a guest" and "the guest" are said in the same way. In relative clauses, however, it is possible to establish the meaning of the definite article through use of some particles.[44]

Remove ads

Vocabulary

Summarize

Perspective

Georgian has a rich word-derivation system. By using a root, and adding some definite prefixes and suffixes, one can derive many nouns and adjectives from the root. For example, from the root -kart-, the following words can be derived: Kartveli ('a Georgian person'), Kartuli ('the Georgian language') and Sakartvelo ('the country of Georgia').

Most Georgian surnames end in -dze 'son' (Western Georgia), -shvili 'child' (Eastern Georgia), -ia (Western Georgia, Samegrelo), -ani (Western Georgia, Svaneti), -uri (Eastern Georgia), etc. The ending -eli is a particle of nobility, comparable to French de, German von or Polish -ski.

Georgian has a vigesimal numeric system like Basque and (partially) French. Numbers greater than 20 and less than 100 are described as the sum of the greatest possible multiple of 20 plus the remainder. For example, "93" literally translates as 'four times twenty plus thirteen' (ოთხმოცდაცამეტი, otkhmotsdatsamet’i).

One of the most important Georgian dictionaries is the Explanatory dictionary of the Georgian language (ქართული ენის განმარტებითი ლექსიკონი). It consists of eight volumes and about 115,000 words. It was produced between 1950 and 1964, by a team of linguists under the direction of Arnold Chikobava.

Remove ads

Examples

Summarize

Perspective

Word formations

Georgian has a word derivation system, which allows the derivation of nouns from verb roots both with prefixes and suffixes, for example:

- From the root -ts’er- 'write', the words ts’erili 'letter' and mts’erali 'writer' are derived.

- From the root -tsa- 'give', the word gadatsema 'broadcast' is derived.

- From the root -tsda- 'try', the word gamotsda 'exam' is derived.

- From the root -gav- 'resemble', the words msgavsi 'similar' and msgavseba 'similarity' are derived.

- From the root -shen- 'build', the word shenoba 'building' is derived.

- From the root -tskh- 'bake', the word namtskhvari 'cake' is derived.

- From the root -tsiv- 'cold', the word matsivari 'refrigerator' is derived.

- From the root -pr- 'fly', the words tvitmprinavi 'airplane' and aprena 'takeoff' are derived.

It is also possible to derive verbs from nouns:

- From the noun -omi- 'war', the verb omob 'you wage/are waging war' is derived.

- From the noun -sadili- 'lunch', the verb sadilob 'you eat/are eating lunch' is derived.

- From the noun -sauzme 'breakfast', the verb ts’asauzmeba 'eating a little breakfast' is derived; the preverb ts’a- in Georgian adds the meaning 'a little'.

- From the noun -sakhli- 'home', the verb gadasakhleba 'relocating, moving' is derived.

Likewise, verbs can be derived from adjectives, for example:

- From the adjective -ts’iteli- 'red', the verb gats’itleba 'blushing, making one blush' is derived. This kind of derivation can be done with many adjectives in Georgian.

- From the adjective -brma 'blind', the verbs dabrmaveba 'becoming blind, blinding someone' are derived.

- From the adjective -lamazi- 'beautiful', the verb galamazeba 'becoming beautiful' is derived.

Words that begin with multiple consonants

In Georgian many nouns and adjectives begin with two or more contiguous consonants. This is because syllables in the language often begin with two consonants. Recordings are available on the relevant Wiktionary entries, linked to below.

- Some examples of words that begin with two consonants are:

- Many words begin with three contiguous consonants:

- A few words in Georgian that begin with four contiguous consonants. Examples are:

- Some extreme cases also exist in Georgian. For example, the following word begins with six contiguous consonants:

- მწვრთნელი (mts’vrtneli), 'trainer'

- While the following word begins with seven:

- გვწვრთნი (gvts’vrtni), 'you train us'

- And the following words begin with eight:

Remove ads

Sample text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:[45]

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads