Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Isaac Asimov

American writer and biochemist (1920–1992) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Isaac Asimov (/ˈæzɪmɒv/ AZ-im-ov;[b][c] c. January 2, 1920[a] – April 6, 1992) was an American writer and professor of biochemistry at Boston University. During his lifetime, Asimov was considered one of the "Big Three" science fiction writers, along with Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke.[2] A prolific writer, he wrote or edited more than 500 books. He also wrote an estimated 90,000 letters and postcards.[d] Best known for his hard science fiction, Asimov also wrote mysteries and fantasy, as well as popular science and other non-fiction.

Asimov's most famous work is the Foundation series,[3] the first three books of which won the one-time Hugo Award for "Best All-Time Series" in 1966.[4] His other major series are the Galactic Empire series and the Robot series. The Galactic Empire novels are set in the much earlier history of the same fictional universe as the Foundation series. Later, with Foundation and Earth (1986), he linked this distant future to the Robot series, creating a unified "future history" for his works.[5] He also wrote more than 380 short stories, including the social science fiction novelette "Nightfall", which in 1964 was voted the best short science fiction story of all time by the Science Fiction Writers of America. Asimov wrote the Lucky Starr series of juvenile science-fiction novels using the pen name Paul French.[6]

Most of his popular science books explain concepts in a historical way, going as far back as possible to a time when the science in question was at its simplest stage. Examples include Guide to Science, the three-volume Understanding Physics, and Asimov's Chronology of Science and Discovery. He wrote on numerous other scientific and non-scientific topics, such as chemistry, astronomy, mathematics, history, biblical exegesis, and literary criticism.

He was the president of the American Humanist Association.[7] Several entities have been named in his honor, including the asteroid (5020) Asimov,[8] a crater on Mars,[9][10] a Brooklyn elementary school,[11] Honda's humanoid robot ASIMO,[12] and four literary awards.

Remove ads

Surname

There are three very simple English words: 'Has', 'him' and 'of'. Put them together like this—'has-him-of'—and say it in the ordinary fashion. Now leave out the two h's and say it again and you have Asimov.

— Asimov, 1979[13]

Asimov's family name derives from the first part of озимый хлеб (ozímyj khleb), meaning 'winter grain' (specifically rye), in which his great-great-great-grandfather dealt, with the Russian surname ending -ov added.[14] Azimov is spelled Азимов in the Cyrillic alphabet.[1] When the family arrived in the United States in 1923 and their name had to be spelled in the Latin alphabet, Asimov's father spelled it with an S, believing this letter to be pronounced like Z (as in German), and so it became Asimov.[1] This later inspired one of Asimov's short stories, "Spell My Name with an S".[15]

Asimov refused early suggestions of using a more common name as a pseudonym, believing that its recognizability helped his career. After becoming famous, he often met readers who believed that "Isaac Asimov" was a distinctive pseudonym created by an author with a common name.[16]

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Early life

Asimov was born in Petrovichi, Russian SFSR,[17] on an unknown date between October 4, 1919, and January 2, 1920, inclusive. Asimov celebrated his birthday on January 2.[a]

Asimov's parents were Russian Jews, Anna Rachel (née Berman) and Judah Asimov, the son of a miller.[18] He was named Isaac after his mother's father, Isaac Berman.[19] Asimov wrote of his father, "My father, for all his education as an Orthodox Jew, was not Orthodox in his heart", noting that "he didn't recite the myriad prayers prescribed for every action, and he never made any attempt to teach them to me."[20]

In 1921, Asimov and 16 other children in Petrovichi developed double pneumonia. Only Asimov survived.[21] He had two younger siblings: a sister, Marcia (born Manya;[22] June 17, 1922 – April 2, 2011),[23] and a brother, Stanley (July 25, 1929 – August 16, 1995), who would become vice-president of Newsday.[24][25]

Asimov's family travelled to the United States via Liverpool on the RMS Baltic, arriving on February 3, 1923[26] when he was three years old. His parents spoke Yiddish and English to him; he never learned Russian, his parents using it as a secret language "when they wanted to discuss something privately that my big ears were not to hear".[27][28] Growing up in Brooklyn, New York, Asimov taught himself to read at the age of five (and later taught his sister to read as well, enabling her to enter school in the second grade).[29] His mother got him into first grade a year early by claiming he was born on September 7, 1919.[30][31] In third grade he learned about the "error" and insisted on an official correction of the date to January 2.[32] He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1928 at the age of eight.[33]

After becoming established in the U.S., his parents owned a succession of candy stores in which everyone in the family was expected to work. The candy stores sold newspapers and magazines, which Asimov credited as a major influence in his lifelong love of the written word, as it presented him as a child with an unending supply of new reading material (including pulp science fiction magazines)[34] that he could not have otherwise afforded. Asimov began reading science fiction at age nine, at the time that the genre was becoming more science-centered.[35] Asimov was also a frequent patron of the Brooklyn Public Library during his formative years.[36]

Education and career

Asimov attended New York City public schools from age five, including Boys High School in Brooklyn.[37] Graduating at 15, he attended the City College of New York for several days before accepting a scholarship at Seth Low Junior College. This was a branch of Columbia University in Downtown Brooklyn designed to absorb some of the academically qualified Jewish and Italian-American students who applied to the more prestigious Columbia College but exceeded the unwritten ethnic admission quotas which were common at the time. Originally a zoology major, Asimov switched to chemistry after his first semester because he disapproved of "dissecting an alley cat". After Seth Low Junior College closed in 1936, Asimov finished his Bachelor of Science degree at Columbia's Morningside Heights campus (later the Columbia University School of General Studies)[38] in 1939. (In 1983, Dr. Robert Pollack [dean of Columbia College, 1982–1989] granted Asimov an honorary doctorate from Columbia College after requiring that Asimov place his foot in a bucket of water to pass the college's swimming requirement.[39])

After two rounds of rejections by medical schools, Asimov applied to the graduate program in chemistry at Columbia in 1939; initially he was rejected and then only accepted on a probationary basis.[40] He completed his Master of Arts degree in chemistry in 1941 and earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in chemistry in 1948.[e][45][46] During his chemistry studies, he also learned French and German.[47]

From 1942 to 1945 during World War II, between his masters and doctoral studies, Asimov worked as a civilian chemist at the Philadelphia Navy Yard's Naval Air Experimental Station and lived in the Walnut Hill section of West Philadelphia.[48][49] In September 1945, he was conscripted into the post-war U.S. Army; if he had not had his birth date corrected while at school, he would have been officially 26 years old and ineligible.[50] In 1946, a bureaucratic error caused his military allotment to be stopped, and he was removed from a task force days before it sailed to participate in Operation Crossroads nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll.[51] He was promoted to corporal on July 11 before receiving an honorable discharge on July 26, 1946.[52][f]

After completing his doctorate and a postdoctoral year with Robert Elderfield,[54] Asimov was offered the position of associate professor of biochemistry at the Boston University School of Medicine. This was in large part due to his years-long correspondence with William Boyd, a former associate professor of biochemistry at Boston University, who initially contacted Asimov to compliment him on his story Nightfall.[55] Upon receiving a promotion to professor of immunochemistry, Boyd reached out to Asimov, requesting him to be his replacement. The initial offer of professorship was withdrawn and Asimov was offered the position of instructor of biochemistry instead, which he accepted.[56] He began work in 1949 with a $5,000 salary[57] (equivalent to $66,000 in 2024), maintaining this position for several years.[58] By 1952, however, he was making more money as a writer than from the university, and he eventually stopped doing research, confining his university role to lecturing students.[g] In 1955, he was promoted to tenured associate professor. In December 1957, Asimov was dismissed from his teaching post, with effect from June 30, 1958, due to his lack of research. After a struggle over two years, he reached an agreement with the university that he would keep his title[60] and give the opening lecture each year for a biochemistry class.[61] On October 18, 1979, the university honored his writing by promoting him to full professor of biochemistry.[62] Asimov's personal papers from 1965 onward are archived at the university's Mugar Memorial Library, to which he donated them at the request of curator Howard Gotlieb.[63][64]

In 1959, after a recommendation from Arthur Obermayer, Asimov's friend and a scientist on the U.S. missile defense project, Asimov was approached by DARPA to join Obermayer's team. Asimov declined on the grounds that his ability to write freely would be impaired should he receive classified information, but submitted a paper to DARPA titled "On Creativity"[65] containing ideas on how government-based science projects could encourage team members to think more creatively.[66]

Personal life

Asimov met his first wife, Gertrude Blugerman, on a blind date on February 14, 1942, and married her on July 26.[67] The couple lived in an apartment in West Philadelphia while Asimov was employed at the Philadelphia Navy Yard (where two of his co-workers were L. Sprague de Camp and Robert A. Heinlein). Gertrude returned to Brooklyn while he was in the Army, and they both lived there from July 1946 before moving to Stuyvesant Town, Manhattan, in July 1948. They moved to Boston in May 1949, then to nearby suburbs Somerville in July 1949, Waltham in May 1951, and, finally, West Newton in 1956.[68] They had two children, David (born 1951) and Robyn Joan (born 1955).[69] In 1970, they separated and Asimov moved back to New York, this time to the Upper West Side of Manhattan where he lived for the rest of his life.[70] He began seeing Janet O. Jeppson, a psychiatrist and science-fiction writer, and married her on November 30, 1973,[71] two weeks after his divorce from Gertrude.[72]

Asimov was a claustrophile: he enjoyed small, enclosed spaces.[73][h] In the third volume of his autobiography, he recalls a childhood desire to own a magazine stand in a New York City Subway station, within which he could enclose himself and listen to the rumble of passing trains while reading.[74]

Asimov was afraid of flying, doing so only twice: once in the course of his work at the Naval Air Experimental Station and once returning home from Oʻahu in 1946. Consequently, he seldom traveled great distances. This phobia influenced several of his fiction works, such as the Wendell Urth mystery stories and the Robot novels featuring Elijah Baley. In his later years, Asimov found enjoyment traveling on cruise ships, beginning in 1972 when he viewed the Apollo 17 launch from a cruise ship.[75] On several cruises, he was part of the entertainment program, giving science-themed talks aboard ships such as the Queen Elizabeth 2.[76] He sailed to England in June 1974 on the SS France for a trip mostly devoted to lectures in London and Birmingham,[77] though he also found time to visit Stonehenge[78] and Shakespeare's birthplace.[79]

"[Sideburns] became a permanent feature of my face, and it is now difficult to believe early photographs that show me without [them]."[80] (Photo by Jay Kay Klein.)

Asimov was a teetotaler.[81]

He was an able public speaker and was regularly invited to give talks about science in his distinct New York accent. He participated in many science fiction conventions, where he was friendly and approachable.[76] He patiently answered tens of thousands of questions and other mail with postcards and was pleased to give autographs. He was of medium height, 5 ft 9 in (1.75 m)[82] and stocky build. In his later years, he adopted a signature style of "mutton-chop" sideburns.[83][84] He took to wearing bolo ties after his wife Janet objected to his clip-on bow ties.[85] He never learned to swim or ride a bicycle, but did learn to drive a car after he moved to Boston. In his humor book Asimov Laughs Again, he describes Boston driving as "anarchy on wheels".[86]

Asimov's wide interests included his participation in later years in organizations devoted to the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan.[76] Many of his short stories mention or quote Gilbert and Sullivan.[87] He was a prominent member of The Baker Street Irregulars, the leading Sherlock Holmes society,[76] for whom he wrote an essay arguing that Professor Moriarty's work "The Dynamics of An Asteroid" involved the willful destruction of an ancient, civilized planet. He was also a member of the male-only literary banqueting club the Trap Door Spiders, which served as the basis of his fictional group of mystery solvers, the Black Widowers.[88] He later used his essay on Moriarty's work as the basis for a Black Widowers story, "The Ultimate Crime", which appeared in More Tales of the Black Widowers.[89][90]

In 1984, the American Humanist Association (AHA) named him the Humanist of the Year. He was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.[91] From 1985 until his death in 1992, he served as honorary president of the AHA, and was succeeded by his friend and fellow writer Kurt Vonnegut. He was also a close friend of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, and earned a screen credit as "special science consultant" on Star Trek: The Motion Picture for his advice during production.[92]

Asimov was a founding member of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, CSICOP (now the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry)[93] and is listed in its Pantheon of Skeptics.[94] In a discussion with James Randi at CSICon 2016 regarding the founding of CSICOP, Kendrick Frazier said that Asimov was "a key figure in the Skeptical movement who is less well known and appreciated today, but was very much in the public eye back then." He said that Asimov's being associated with CSICOP "gave it immense status and authority" in his eyes.[95]: 13:00

Asimov described Carl Sagan as one of only two people he ever met whose intellect surpassed his own. The other, he claimed, was the computer scientist and artificial intelligence expert Marvin Minsky.[96] Asimov was an on-and-off member and honorary vice president of Mensa International, albeit reluctantly;[97] he described some members of that organization as "brain-proud and aggressive about their IQs".[98][i]

After his father died in 1969, Asimov annually contributed to a Judah Asimov Scholarship Fund at Brandeis University.[101]

In 2006, he was named by Carnegie Corporation of New York to the inaugural class of winners of the Great Immigrants Award.[102]

Illness and death

In 1977, Asimov had a heart attack. In December 1983, he had triple bypass surgery at NYU Medical Center, during which he contracted HIV from a blood transfusion.[103] His HIV status was kept secret out of concern that the anti-AIDS prejudice might extend to his family members.[104]

He died in Manhattan on April 6, 1992,[105] and was cremated.[106] The cause of death was reported as heart and kidney failure.[107][108][109] Ten years following Asimov's death, Janet and Robyn Asimov agreed that the HIV story should be made public; Janet revealed it in her edition of his autobiography, It's Been a Good Life.[103][109][104]

Remove ads

Writings

Summarize

Perspective

[T]he only thing about myself that I consider to be severe enough to warrant psychoanalytic treatment is my compulsion to write ... That means that my idea of a pleasant time is to go up to my attic, sit at my electric typewriter (as I am doing right now), and bang away, watching the words take shape like magic before my eyes.

— Asimov, 1969[110]

Overview

Asimov's career can be divided into several periods. His early career, dominated by science fiction, began with short stories in 1939 and novels in 1950. This lasted until about 1958, all but ending after publication of The Naked Sun (1957). He began publishing nonfiction as co-author of a college-level textbook called Biochemistry and Human Metabolism. Following the brief orbit of the first human-made satellite Sputnik I by the USSR in 1957, he wrote more nonfiction, particularly popular science books, and less science fiction. Over the next quarter-century, he wrote only four science fiction novels, and 120 nonfiction books.

Starting in 1982, the second half of his science fiction career began with the publication of Foundation's Edge. From then until his death, Asimov published several more sequels and prequels to his existing novels, tying them together in a way he had not originally anticipated, making a unified series. There are many inconsistencies in this unification, especially in his earlier stories.[111] Doubleday and Houghton Mifflin published about 60% of his work up to 1969, Asimov stating that "both represent a father image".[61]

Asimov believed his most enduring contributions would be his "Three Laws of Robotics" and the Foundation series.[112] The Oxford English Dictionary credits his science fiction for introducing into the English language the words "robotics", "positronic" (an entirely fictional technology), and "psychohistory" (which is also used for a different study on historical motivations). Asimov coined the term "robotics" without suspecting that it might be an original word; at the time, he believed it was simply the natural analogue of words such as mechanics and hydraulics, but for robots. Unlike his word "psychohistory", the word "robotics" continues in mainstream technical use with Asimov's original definition. Star Trek: The Next Generation featured androids with "positronic brains" and the first-season episode "Datalore" called the positronic brain "Asimov's dream".[113]

Asimov was so prolific and diverse in his writing that his books span all major categories of the Dewey Decimal Classification except for category 100, philosophy and psychology.[114] However, he wrote several essays about psychology,[115] and forewords for the books The Humanist Way (1988) and In Pursuit of Truth (1982),[116] which were classified in the 100s category, but none of his own books were classified in that category.[114]

According to UNESCO's Index Translationum database, Asimov is the world's 24th-most-translated author.[117]

Science fiction

No matter how various the subject matter I write on, I was a science-fiction writer first and it is as a science-fiction writer that I want to be identified.

— Asimov, 1980[118]

Asimov became a science fiction fan in 1929,[119] when he began reading the pulp magazines sold in his family's candy store.[120] At first his father forbade reading pulps until Asimov persuaded him that because the science fiction magazines had "Science" in the title, they must be educational.[121] At age 18 he joined the Futurians science fiction fan club, where he made friends who went on to become science fiction writers or editors.[122]

Asimov began writing at the age of 11, imitating The Rover Boys with eight chapters of The Greenville Chums at College. His father bought him a used typewriter at age 16.[61] His first published work was a humorous item on the birth of his brother for Boys High School's literary journal in 1934. In May 1937 he first thought of writing professionally, and began writing his first science fiction story, "Cosmic Corkscrew" (now lost), that year. On May 17, 1938, puzzled by a change in the schedule of Astounding Science Fiction, Asimov visited its publisher Street & Smith Publications. Inspired by the visit, he finished the story on June 19, 1938, and personally submitted it to Astounding editor John W. Campbell two days later. Campbell met with Asimov for more than an hour and promised to read the story himself. Two days later he received a detailed rejection letter.[119] This was the first of what became almost weekly meetings with the editor while Asimov lived in New York, until moving to Boston in 1949;[57] Campbell had a strong formative influence on Asimov and became a personal friend.[123]

By the end of the month, Asimov completed a second story, "Stowaway". Campbell rejected it on July 22 but—in "the nicest possible letter you could imagine"—encouraged him to continue writing, promising that Asimov might sell his work after another year and a dozen stories of practice.[119] On October 21, 1938, he sold the third story he finished, "Marooned Off Vesta", to Amazing Stories, edited by Raymond A. Palmer, and it appeared in the March 1939 issue. Asimov was paid $64 (equivalent to $1,430 in 2024), or one cent a word.[61][124] Two more stories appeared that year, "The Weapon Too Dreadful to Use" in the May Amazing and "Trends" in the July Astounding, the issue fans later selected as the start of the Golden Age of Science Fiction.[16] For 1940, ISFDB catalogs seven stories in four different pulp magazines, including one in Astounding.[125] His earnings became enough to pay for his education, but not yet enough for him to become a full-time writer.[124]

He later said that unlike other Golden Age writers Heinlein and A. E. van Vogt—also first published in 1939, and whose talent and stardom were immediately obvious—Asimov "(this is not false modesty) came up only gradually".[16] Through July 29, 1940, Asimov wrote 22 stories in 25 months, of which 13 were published; he wrote in 1972 that from that date he never wrote a science fiction story that was not published (except for two "special cases"[j]).[128] By 1941 Asimov was famous enough that Donald Wollheim told him that he purchased "The Secret Sense" for a new magazine only because of his name,[129] and the December 1940 issue of Astonishing—featuring Asimov's name in bold—was the first magazine to base cover art on his work,[130] but Asimov later said that neither he nor anyone else—except perhaps Campbell—considered him better than an often published "third rater".[131]

Based on a conversation with Campbell, Asimov wrote "Nightfall", his 32nd story, in March and April 1941, and Astounding published it in September 1941. In 1968 the Science Fiction Writers of America voted "Nightfall" the best science fiction short story ever written.[107][131] In Nightfall and Other Stories Asimov wrote, "The writing of 'Nightfall' was a watershed in my professional career ... I was suddenly taken seriously and the world of science fiction became aware that I existed. As the years passed, in fact, it became evident that I had written a 'classic'."[132] "Nightfall" is an archetypal example of social science fiction, a term he created to describe a new trend in the 1940s, led by authors including him and Heinlein, away from gadgets and space opera and toward speculation about the human condition.[133]

After writing "Victory Unintentional" in January and February 1942, Asimov did not write another story for a year. He expected to make chemistry his career, and was paid $2,600 annually at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, enough to marry his girlfriend; he did not expect to make much more from writing than the $1,788.50 he had earned from the 28 stories he had already sold over four years. Asimov left science fiction fandom and no longer read new magazines, and might have left the writing profession had not Heinlein and de Camp been his coworkers at the Navy Yard and previously sold stories continued to appear.[134]

In 1942, Asimov published the first of his Foundation stories—later collected in the Foundation trilogy: Foundation (1951), Foundation and Empire (1952), and Second Foundation (1953). The books describe the fall of a vast interstellar empire and the establishment of its eventual successor. They feature his fictional science of psychohistory, whose theories could predict the future course of history according to dynamical laws regarding the statistical analysis of mass human actions.[135]

Campbell raised his rate per word, Orson Welles purchased rights to "Evidence", and anthologies reprinted his stories. By the end of the war Asimov was earning as a writer an amount equal to half of his Navy Yard salary, even after a raise, but Asimov still did not believe that writing could support him, his wife, and future children.[136][137]

His "positronic" robot stories—many of which were collected in I, Robot (1950)—were begun at about the same time. They promulgated a set of rules of ethics for robots (see Three Laws of Robotics) and intelligent machines that greatly influenced other writers and thinkers in their treatment of the subject. Asimov notes in his introduction to the short story collection The Complete Robot (1982) that he was largely inspired by the tendency of robots up to that time to fall consistently into a Frankenstein plot in which they destroyed their creators. The Robot series has led to film adaptations. With Asimov's collaboration, in about 1977, Harlan Ellison wrote a screenplay of I, Robot that Asimov hoped would lead to "the first really adult, complex, worthwhile science fiction film ever made". The screenplay has never been filmed and was eventually published in book form in 1994. The 2004 movie I, Robot, starring Will Smith, was based on an unrelated script by Jeff Vintar titled Hardwired, with Asimov's ideas incorporated later after the rights to Asimov's title were acquired.[138] (The title was not original to Asimov but had previously been used for a story by Eando Binder.) Also, one of Asimov's robot short stories, "The Bicentennial Man", was expanded into a novel The Positronic Man by Asimov and Robert Silverberg, and this was adapted into the 1999 movie Bicentennial Man, starring Robin Williams.[92]

In 1966 the Foundation trilogy won the Hugo Award for the all-time best series of science fiction and fantasy novels,[139] and they along with the Robot series are his most famous science fiction. Besides movies, his Foundation and Robot stories have inspired other derivative works of science fiction literature, many by well-known and established authors such as Roger MacBride Allen, Greg Bear, Gregory Benford, David Brin, and Donald Kingsbury. At least some of these appear to have been done with the blessing of, or at the request of, Asimov's widow, Janet Asimov.[140][141][142]

In 1948, he also wrote a spoof chemistry article, "The Endochronic Properties of Resublimated Thiotimoline". At the time, Asimov was preparing his own doctoral dissertation, which would include an oral examination. Fearing a prejudicial reaction from his graduate school evaluation board at Columbia University, Asimov asked his editor that it be released under a pseudonym. When it nevertheless appeared under his own name, Asimov grew concerned that his doctoral examiners might think he wasn't taking science seriously. At the end of the examination, one evaluator turned to him, smiling, and said, "What can you tell us, Mr. Asimov, about the thermodynamic properties of the compound known as thiotimoline". Laughing hysterically with relief, Asimov had to be led out of the room. After a five-minute wait, he was summoned back into the room and congratulated as "Dr. Asimov".[143]

Demand for science fiction greatly increased during the 1950s, making it possible for a genre author to write full-time.[144] In 1949, book publisher Doubleday's science fiction editor Walter I. Bradbury accepted Asimov's unpublished "Grow Old with Me" (40,000 words), but requested that it be extended to a full novel of 70,000 words. The book appeared under the Doubleday imprint in January 1950 with the title of Pebble in the Sky.[57] Doubleday published five more original science fiction novels by Asimov in the 1950s, along with the six juvenile Lucky Starr novels, the latter under the pseudonym "Paul French".[145] Doubleday also published collections of Asimov's short stories, beginning with The Martian Way and Other Stories in 1955. The early 1950s also saw Gnome Press publish one collection of Asimov's positronic robot stories as I, Robot and his Foundation stories and novelettes as the three books of the Foundation trilogy. More positronic robot stories were republished in book form as The Rest of the Robots.

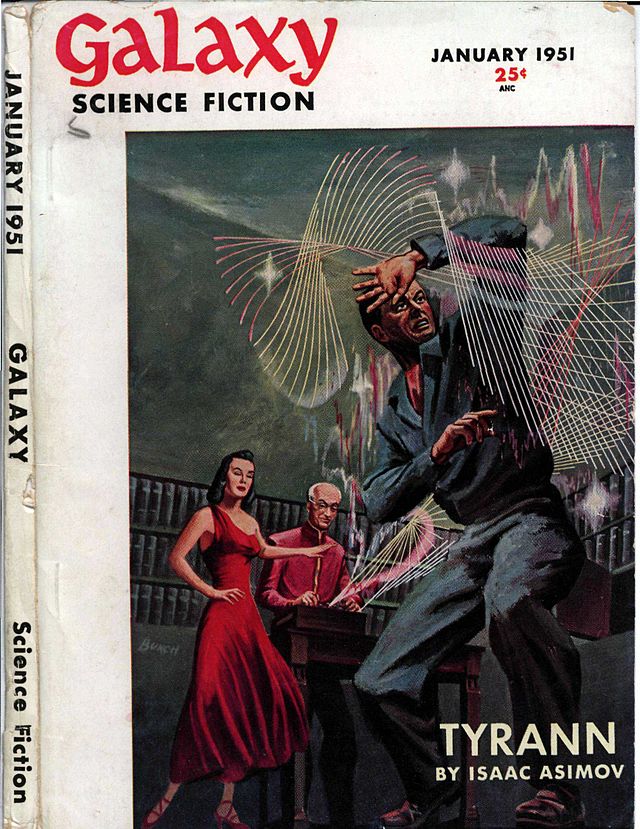

Book publishers and the magazines Galaxy and Fantasy & Science Fiction ended Asimov's dependence on Astounding. He later described the era as his "'mature' period". Asimov's "The Last Question" (1956), on the ability of humankind to cope with and potentially reverse the process of entropy, was his personal favorite story.[146]

In 1972, his stand-alone novel The Gods Themselves was published to general acclaim, winning Best Novel in the Hugo,[147] Nebula,[147] and Locus Awards.[148]

In December 1974, former Beatle Paul McCartney approached Asimov and asked him to write the screenplay for a science-fiction movie musical. McCartney had a vague idea for the plot and a small scrap of dialogue, about a rock band whose members discover they are being impersonated by extraterrestrials. The band and their impostors would likely be played by McCartney's group Wings, then at the height of their career. Though not generally a fan of rock music, Asimov was intrigued by the idea and quickly produced a treatment outline of the story adhering to McCartney's overall idea but omitting McCartney's scrap of dialogue. McCartney rejected it, and the treatment now exists only in the Boston University archives.[149]

Asimov said in 1969 that he had "the happiest of all my associations with science fiction magazines" with Fantasy & Science Fiction; "I have no complaints about Astounding, Galaxy, or any of the rest, heaven knows, but F&SF has become something special to me".[150] Beginning in 1977, Asimov lent his name to Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine (now Asimov's Science Fiction) and wrote an editorial for each issue. There was also a short-lived Asimov's SF Adventure Magazine and a companion Asimov's Science Fiction Anthology reprint series, published as magazines (in the same manner as the stablemates Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine's and Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine's "anthologies").[151]

Due to pressure by fans on Asimov to write another book in his Foundation series,[58] he did so with Foundation's Edge (1982) and Foundation and Earth (1986), and then went back to before the original trilogy with Prelude to Foundation (1988) and Forward the Foundation (1992), his last novel.

He also helped Leonard Nimoy fleshing out the premise of the science fiction comic Primortals (1995–1997).[152]

Popular science

Just say I am one of the most versatile writers in the world, and the greatest popularizer of many subjects.

— Asimov, 1969[61]

Asimov and two colleagues published a textbook in 1949, with two more editions by 1969.[61] During the late 1950s and 1960s, Asimov substantially decreased his fiction output (he published only four adult novels between 1957's The Naked Sun and 1982's Foundation's Edge, two of which were mysteries). He greatly increased his nonfiction production, writing mostly on science topics; the launch of Sputnik in 1957 engendered public concern over a "science gap".[153] Asimov explained in The Rest of the Robots that he had been unable to write substantial fiction since the summer of 1958, and observers understood him as saying that his fiction career had ended, or was permanently interrupted.[154] Asimov recalled in 1969 that "the United States went into a kind of tizzy, and so did I. I was overcome by the ardent desire to write popular science for an America that might be in great danger through its neglect of science, and a number of publishers got an equally ardent desire to publish popular science for the same reason".[155]

Fantasy and Science Fiction invited Asimov to continue his regular nonfiction column, begun in the now-folded bimonthly companion magazine Venture Science Fiction Magazine. The first of 399 monthly F&SF columns appeared in November 1958 and they continued until his terminal illness.[156][k] These columns, periodically collected into books by Doubleday,[61] gave Asimov a reputation as a "Great Explainer" of science; he described them as his only popular science writing in which he never had to assume complete ignorance of the subjects on the part of his readers. The column was ostensibly dedicated to popular science but Asimov had complete editorial freedom, and wrote about contemporary social issues[citation needed] in essays such as "Thinking About Thinking"[157] and "Knock Plastic!".[158] In 1975 he wrote of these essays: "I get more pleasure out of them than out of any other writing assignment."[159]

Asimov's first wide-ranging reference work, The Intelligent Man's Guide to Science (1960), was nominated for a National Book Award, and in 1963 he won a Hugo Award—his first—for his essays for F&SF.[160] The popularity of his science books and the income he derived from them allowed him to give up most academic responsibilities and become a full-time freelance writer.[161] He encouraged other science fiction writers to write popular science, stating in 1967 that "the knowledgeable, skillful science writer is worth his weight in contracts", with "twice as much work as he can possibly handle".[162]

The great variety of information covered in Asimov's writings prompted Kurt Vonnegut to ask, "How does it feel to know everything?" Asimov replied that he only knew how it felt to have the 'reputation' of omniscience: "Uneasy".[163] Floyd C. Gale said that "Asimov has a rare talent. He can make your mental mouth water over dry facts",[164] and "science fiction's loss has been science popularization's gain".[165] Asimov said that "Of all the writing I do, fiction, non-fiction, adult, or juvenile, these F & SF articles are by far the most fun".[166] He regretted, however, that he had less time for fiction—causing dissatisfied readers to send him letters of complaint—stating in 1969 that "In the last ten years, I've done a couple of novels, some collections, a dozen or so stories, but that's nothing".[155]

In his essay "To Tell a Chemist" (1965), Asimov proposed a simple shibboleth for distinguishing chemists from non-chemists: ask the person to read the word "unionized". Chemists, he noted, will read un-ionized (electrically neutral), while non-chemists will read union-ized (belonging to a trade union).

Coined terms

Asimov coined the term "robotics" in his May 1941 story "Liar!",[167] though he later remarked that he believed then that he was merely using an existing word, as he stated in Gold ("The Robot Chronicles"). While acknowledging the Oxford Dictionary reference, he incorrectly states that the word was first printed about one third of the way down the first column of page 100 in the March 1942 issue of Astounding Science Fiction – the printing of his short story "Runaround".[168][169]

In the same story, Asimov also coined the term "positronic" (the counterpart to "electronic" for positrons).[170]

Asimov coined the term "psychohistory" in his Foundation stories to name a fictional branch of science which combines history, sociology, and mathematical statistics to make general predictions about the future behavior of very large groups of people, such as the Galactic Empire. Asimov said later that he should have called it psychosociology. It was first introduced in the five short stories (1942–1944) which would later be collected as the 1951 fix-up novel Foundation.[171] Somewhat later, the term "psychohistory" was applied by others to research of the effects of psychology on history.[172][173]

Other writings

In addition to his interest in science, Asimov was interested in history. Starting in the 1960s, he wrote 14 popular history books, including The Greeks: A Great Adventure (1965),[174] The Roman Republic (1966),[175] The Roman Empire (1967),[176] The Egyptians (1967)[177] The Near East: 10,000 Years of History (1968),[178] and Asimov's Chronology of the World (1991).[179]

He published Asimov's Guide to the Bible in two volumes—covering the Old Testament in 1967 and the New Testament in 1969—and then combined them into one 1,300-page volume in 1981. Complete with maps and tables, the guide goes through the books of the Bible in order, explaining the history of each one and the political influences that affected it, as well as biographical information about the important characters. His interest in literature manifested itself in several annotations of literary works, including Asimov's Guide to Shakespeare (1970),[l] Asimov's Annotated Don Juan (1972), Asimov's Annotated Paradise Lost (1974), and The Annotated Gulliver's Travels (1980).[180]

Asimov was also a noted mystery author and a frequent contributor to Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. He began by writing science fiction mysteries such as his Wendell Urth stories, but soon moved on to writing "pure" mysteries. He published two full-length mystery novels, and wrote 66 stories about the Black Widowers, a group of men who met monthly for dinner, conversation, and a puzzle. He got the idea for the Widowers from his own association in a stag group called the Trap Door Spiders, and all of the main characters (with the exception of the waiter, Henry, who he admitted resembled Wodehouse's Jeeves) were modeled after his closest friends.[181] A parody of the Black Widowers, "An Evening with the White Divorcés," was written by author, critic, and librarian Jon L. Breen.[182] Asimov joked, "all I can do ... is to wait until I catch him in a dark alley, someday."[183]

Toward the end of his life, Asimov published a series of collections of limericks, mostly written by himself, starting with Lecherous Limericks, which appeared in 1975. Limericks: Too Gross, whose title displays Asimov's love of puns, contains 144 limericks by Asimov and an equal number by John Ciardi. He even created a slim volume of Sherlockian limericks. Asimov featured Yiddish humor in Azazel, The Two Centimeter Demon. The two main characters, both Jewish, talk over dinner, or lunch, or breakfast, about anecdotes of "George" and his friend Azazel. Asimov's Treasury of Humor is both a working joke book and a treatise propounding his views on humor theory. According to Asimov, the most essential element of humor is an abrupt change in point of view, one that suddenly shifts focus from the important to the trivial, or from the sublime to the ridiculous.[184][185]

Particularly in his later years, Asimov to some extent cultivated an image of himself as an amiable lecher. In 1971, as a response to the popularity of sexual guidebooks such as The Sensuous Woman (by "J") and The Sensuous Man (by "M"), Asimov published The Sensuous Dirty Old Man under the byline "Dr. 'A'"[186] (although his full name was printed on the paperback edition, first published 1972). However, by 2016, Asimov's habit of groping women was seen as sexual harassment and came under criticism, and was cited as an early example of inappropriate behavior that can occur at science fiction conventions.[187]

Asimov published three volumes of autobiography. In Memory Yet Green (1979)[188] and In Joy Still Felt (1980)[189] cover his life up to 1978. The third volume, I. Asimov: A Memoir (1994),[190] covered his whole life (rather than following on from where the second volume left off). The epilogue was written by his widow Janet Asimov after his death. The book won a Hugo Award in 1995.[191] Janet Asimov edited It's Been a Good Life (2002),[192] a condensed version of his three autobiographies. He also published three volumes of retrospectives of his writing, Opus 100 (1969),[193] Opus 200 (1979),[194] and Opus 300 (1984).[195]

In 1987, the Asimovs co-wrote How to Enjoy Writing: A Book of Aid and Comfort. In it they offer advice on how to maintain a positive attitude and stay productive when dealing with discouragement, distractions, rejection, and thick-headed editors. The book includes many quotations, essays, anecdotes, and husband-wife dialogues about the ups and downs of being an author.[196][197]

Asimov and Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry developed a unique relationship during Star Trek's initial launch in the late 1960s. Asimov wrote a critical essay on Star Trek's scientific accuracy for TV Guide magazine. Roddenberry retorted respectfully with a personal letter explaining the limitations of accuracy when writing a weekly series. Asimov corrected himself with a follow-up essay to TV Guide claiming that despite its inaccuracies, Star Trek was a fresh and intellectually challenging science fiction television show. The two remained friends to the point where Asimov even served as an advisor on a number of Star Trek projects.[198]

In 1973, Asimov published a proposal for calendar reform, called the World Season Calendar. It divides the year into four seasons (named A–D) of 13 weeks (91 days) each. This allows days to be named, e.g., "D-73" instead of December 1 (due to December 1 being the 73rd day of the 4th quarter). An extra 'year day' is added for a total of 365 days.[199]

Awards and recognition

Asimov won more than a dozen annual awards for particular works of science fiction and a half-dozen lifetime awards.[200] He also received 14 honorary doctorate degrees from universities.[201]

- 1955 – Guest of Honor at the 13th World Science Fiction Convention[202]

- 1957 – Thomas Alva Edison Foundation Award for best science book for youth, for Building Blocks of the Universe[203]

- 1960 – Howard W. Blakeslee Award from the American Heart Association for The Living River[204]

- 1962 – Boston University's Publication Merit Award[205]

- 1963 – A special Hugo Award for "adding science to science fiction," for essays published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction[160]

- 1963 – Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[206]

- 1964 – The Science Fiction Writers of America voted "Nightfall" (1941) the all-time best science fiction short story[107]

- 1965 – James T. Grady Award of the American Chemical Society (now called the James T. Grady-James H. Stack Award for Interpreting Chemistry)[207]

- 1966 – Best All-time Novel Series Hugo Award for the Foundation trilogy[208]

- 1967 – Edward E. Smith Memorial Award[209]

- 1967 – AAAS-Westinghouse Science Writing Award for Magazine Writing, for essay "Over the Edge of the Universe"[m] (in the March 1967 Harper's Magazine)[210]

- 1972 – Nebula Award for Best Novel for The Gods Themselves[211]

- 1973 – Hugo Award for Best Novel for The Gods Themselves[211]

- 1973 – Locus Award for Best Novel for The Gods Themselves[211]

- 1975 – Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[212]

- 1975 – Klumpke-Roberts Award "for outstanding contributions to the public understanding and appreciation of astronomy"[213]

- 1975 – Locus Award for Best Reprint Anthology for Before the Golden Age[214]

- 1977 – Hugo Award for Best Novelette for The Bicentennial Man[215]

- 1977 – Nebula Award for Best Novelette for The Bicentennial Man[216]

- 1977 – Locus Award for Best Novelette for The Bicentennial Man[217]

- 1981 – An asteroid, 5020 Asimov, was named in his honor[8]

- 1981 – Locus Award for Best Non-Fiction Book for In Joy Still Felt: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978[214]

- 1983 – Hugo Award for Best Novel for Foundation's Edge[218]

- 1983 – Locus Award for Best Science Fiction Novel for Foundation's Edge[218]

- 1984 – Humanist of the Year[219]

- 1986 – The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America named him its 8th SFWA Grand Master (presented in 1987).[220]

- 1987 – Locus Award for Best Short Story for "Robot Dreams"[221]

- 1992 – Hugo Award for Best Novelette for "Gold"[222]

- 1995 – Hugo Award for Best Non-Fiction Book for I. Asimov: A Memoir[223]

- 1995 – Locus Award for Best Non-Fiction Book for I. Asimov: A Memoir[214]

- 1996 – A 1946 Retro-Hugo for Best Novel of 1945 was given at the 1996 WorldCon for "The Mule", the 7th Foundation story, published in Astounding Science Fiction[224]

- 1997 – The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted Asimov in its second class of two deceased and two living persons, along with H. G. Wells.[225]

- 2000 – Asimov was featured on a stamp in Israel[226]

- 2001 – The Isaac Asimov Memorial Debates at the Hayden Planetarium in New York were inaugurated

- 2009 – A crater on the planet Mars, Asimov,[9] was named in his honor

- 2010 – In the US Congress bill about the designation of the National Robotics Week as an annual event, a tribute to Isaac Asimov is as follows:

- "Whereas the second week in April each year is designated as 'National Robotics Week', recognizing the accomplishments of Isaac Asimov, who immigrated to America, taught science, wrote science books for children and adults, first used the term robotics, developed the Three Laws of Robotics, and died in April 1992: Now, therefore, be it resolved ..."[227]

- 2015 – Selected as a member of the New York State Writers Hall of Fame.[228]

- 2016 – A 1941 Retro-Hugo for Best Short Story of 1940 was given at the 2016 WorldCon for Robbie, his first positronic robot story, published in Super Science Stories, September 1940[229]

- 2018 – A 1943 Retro-Hugo for Best Short Story of 1942 was given at the 2018 WorldCon for Foundation, published in Astounding Science-Fiction, May 1942[230]

Remove ads

Writing style

Summarize

Perspective

I have an informal style, which means I tend to use short words and simple sentence structure, to say nothing of occasional colloquialisms. This grates on people who like things that are poetic, weighty, complex, and, above all, obscure. On the other hand, the informal style pleases people who enjoy the sensation of reading an essay without being aware that they are reading and of feeling that ideas are flowing from the writer's brain into their own without mental friction.

— Asimov, 1980[231]

Asimov was his own secretary, typist, indexer, proofreader, and literary agent.[61] He wrote a typed first draft composed at the keyboard at 90 words per minute; he imagined an ending first, then a beginning, then "let everything in-between work itself out as I come to it". (Asimov used an outline only once, later describing it as "like trying to play the piano from inside a straitjacket".) After correcting a draft by hand, he retyped the document as the final copy and only made one revision with minor editor-requested changes; a word processor did not save him much time, Asimov said, because 95% of the first draft was unchanged.[146][232][233]

After disliking making multiple revisions of "Black Friar of the Flame", Asimov refused to make major, second, or non-editorial revisions ("like chewing used gum"), stating that "too large a revision, or too many revisions, indicate that the piece of writing is a failure. In the time it would take to salvage such a failure, I could write a new piece altogether and have infinitely more fun in the process". He submitted "failures" to another editor.[146][232]

Asimov's fiction style is extremely unornamented. In 1980, science fiction scholar James Gunn wrote of I, Robot:

Except for two stories—"Liar!" and "Evidence"—they are not stories in which character plays a significant part. Virtually all plot develops in conversation with little if any action. Nor is there a great deal of local color or description of any kind. The dialogue is, at best, functional and the style is, at best, transparent. ... . The robot stories and, as a matter of fact, almost all Asimov fiction—play themselves on a relatively bare stage.[234]

Asimov addressed such criticism in 1989 at the beginning of Nemesis:

I made up my mind long ago to follow one cardinal rule in all my writing—to be 'clear'. I have given up all thought of writing poetically or symbolically or experimentally, or in any of the other modes that might (if I were good enough) get me a Pulitzer prize. I would write merely clearly and in this way establish a warm relationship between myself and my readers, and the professional critics—Well, they can do whatever they wish.[235]

Gunn cited examples of a more complex style, such as the climax of "Liar!". Sharply drawn characters occur at key junctures of his storylines: Susan Calvin in "Liar!" and "Evidence", Arkady Darell in Second Foundation, Elijah Baley in The Caves of Steel, and Hari Seldon in the Foundation prequels.

Other than books by Gunn and Joseph Patrouch, there is relatively little literary criticism on Asimov (particularly when compared to the sheer volume of his output). Cowart and Wymer's Dictionary of Literary Biography (1981) gives a possible reason:

His words do not easily lend themselves to traditional literary criticism because he has the habit of centering his fiction on plot and clearly stating to his reader, in rather direct terms, what is happening in his stories and why it is happening. In fact, most of the dialogue in an Asimov story, and particularly in the Foundation trilogy, is devoted to such exposition. Stories that clearly state what they mean in unambiguous language are the most difficult for a scholar to deal with because there is little to be interpreted.[236]

Gunn's and Patrouch's studies of Asimov both state that a clear, direct prose style is still a style. Gunn's 1982 book comments in detail on each of Asimov's novels. He does not praise all of Asimov's fiction (nor does Patrouch), but calls some passages in The Caves of Steel "reminiscent of Proust". When discussing how that novel depicts night falling over futuristic New York City, Gunn says that Asimov's prose "need not be ashamed anywhere in literary society".[237]

Although he prided himself on his unornamented prose style (for which he credited Clifford D. Simak as an early influence[16][238]), and said in 1973 that his style had not changed,[146] Asimov also enjoyed giving his longer stories complicated narrative structures, often by arranging chapters in nonchronological ways. Some readers have been put off by this, complaining that the nonlinearity is not worth the trouble and adversely affects the clarity of the story. For example, the first third of The Gods Themselves begins with Chapter 6, then backtracks to fill in earlier material.[239] (John Campbell advised Asimov to begin his stories as late in the plot as possible. This advice helped Asimov create "Reason", one of the early Robot stories). Patrouch found that the interwoven and nested flashbacks of The Currents of Space did serious harm to that novel, to such an extent that only a "dyed-in-the-kyrt[240] Asimov fan" could enjoy it. In his later novel Nemesis one group of characters lives in the "present" and another group starts in the "past", beginning 15 years earlier and gradually moving toward the time of the first group.

Alien life

Asimov once explained that his reluctance to write about aliens came from an incident early in his career when Astounding's editor John Campbell rejected one of his science fiction stories because the alien characters were portrayed as superior to the humans. The nature of the rejection led him to believe that Campbell may have based his bias towards humans in stories on a real-world racial bias. Unwilling to write only weak alien races, and concerned that a confrontation would jeopardize his and Campbell's friendship, he decided he would not write about aliens at all.[241] Nevertheless, in response to these criticisms, he wrote The Gods Themselves, which contains aliens and alien sex. The book won the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 1972,[211] and the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1973.[211] Asimov said that of all his writings, he was most proud of the middle section of The Gods Themselves, the part that deals with those themes.[242]

In the Hugo Award–winning novelette "Gold", Asimov describes an author, based on himself, who has one of his books (The Gods Themselves) adapted into a "compu-drama", essentially photo-realistic computer animation. The director criticizes the fictionalized Asimov ("Gregory Laborian") for having an extremely nonvisual style, making it difficult to adapt his work, and the author explains that he relies on ideas and dialogue rather than description to get his points across.[243]

Romance and women

In the early days of science fiction some authors and critics felt that the romantic elements were inappropriate in science fiction stories, which were supposedly to be focused on science and technology. Isaac Asimov was a supporter of this point of view, expressed in his 1938-1939 letters to Astounding, where he described such elements as "mush" and "slop". To his dismay, these letters were met with a strong opposition.[244]

Asimov attributed the lack of romance and sex in his fiction to the "early imprinting" from starting his writing career when he had never been on a date and "didn't know anything about girls".[124] He was sometimes criticized for the general absence of sex (and of extraterrestrial life) in his science fiction. He claimed he wrote The Gods Themselves (1972) to respond to these criticisms,[245] which often came from New Wave science fiction (and often British) writers. The second part (of three) of the novel is set on an alien world with three sexes, and the sexual behavior of these creatures is extensively depicted.

Remove ads

Views

Summarize

Perspective

There is a perennial question among readers as to whether the views contained in a story reflect the views of the author. The answer is, "Not necessarily—" And yet one ought to add another short phrase "—but usually."

— Asimov, 1969[246]

Religion

Asimov was an atheist, and a humanist.[116] He did not oppose religious conviction in others, but he frequently railed against superstitious and pseudoscientific beliefs that tried to pass themselves off as genuine science. During his childhood, his parents observed the traditions of Orthodox Judaism less stringently than they had in Petrovichi; they did not force their beliefs upon young Isaac, and he grew up without strong religious influences, coming to believe that the Torah represented Hebrew mythology in the same way that the Iliad recorded Greek mythology.[247] When he was 13, he chose not to have a bar mitzvah.[248] As his books Treasury of Humor and Asimov Laughs Again record, Asimov was willing to tell jokes involving God, Satan, the Garden of Eden, Jerusalem, and other religious topics, expressing the viewpoint that a good joke can do more to provoke thought than hours of philosophical discussion.[184][185]

For a brief while, his father worked in the local synagogue to enjoy the familiar surroundings and, as Isaac put it, "shine as a learned scholar"[249] versed in the sacred writings. This scholarship was a seed for his later authorship and publication of Asimov's Guide to the Bible, an analysis of the historic foundations for the Old and New Testaments. For many years, Asimov called himself an atheist; he considered the term somewhat inadequate, as it described what he did not believe rather than what he did. Eventually, he described himself as a "humanist" and considered that term more practical. Asimov continued to identify himself as a secular Jew, as stated in his introduction to Jack Dann's anthology of Jewish science fiction, Wandering Stars: "I attend no services and follow no ritual and have never undergone that curious puberty rite, the Bar Mitzvah. It doesn't matter. I am Jewish."[250]

When asked in an interview in 1982 if he was an atheist, Asimov replied,

I am an atheist, out and out. It took me a long time to say it. I've been an atheist for years and years, but somehow I felt it was intellectually unrespectable to say one was an atheist, because it assumed knowledge that one didn't have. Somehow it was better to say one was a humanist or an agnostic. I finally decided that I'm a creature of emotion as well as of reason. Emotionally I am an atheist. I don't have the evidence to prove that God doesn't exist, but I so strongly suspect he doesn't that I don't want to waste my time.[251]

Likewise, he said about religious education: "I would not be satisfied to have my kids choose to be religious without trying to argue them out of it, just as I would not be satisfied to have them decide to smoke regularly or engage in any other practice I consider detrimental to mind or body."[252]

In his last volume of autobiography, Asimov wrote,

If I were not an atheist, I would believe in a God who would choose to save people on the basis of the totality of their lives and not the pattern of their words. I think he would prefer an honest and righteous atheist to a TV preacher whose every word is God, God, God, and whose every deed is foul, foul, foul.[253]

The same memoir states his belief that Hell is "the drooling dream of a sadist" crudely affixed to an all-merciful God; if even human governments were willing to curtail cruel and unusual punishments, wondered Asimov, why would punishment in the afterlife not be restricted to a limited term? Asimov rejected the idea that a human belief or action could merit infinite punishment. If an afterlife existed, he claimed, the longest and most severe punishment would be reserved for those who "slandered God by inventing Hell".[254]

Asimov said about using religious motifs in his writing:

I tend to ignore religion in my own stories altogether, except when I absolutely have to have it. ... and, whenever I bring in a religious motif, that religion is bound to seem vaguely Christian because that is the only religion I know anything about, even though it is not mine. An unsympathetic reader might think that I am "burlesquing" Christianity, but I am not. Then too, it is impossible to write science fiction and really ignore religion.[255]

Politics

Asimov became a staunch supporter of the Democratic Party during the New Deal, and thereafter remained a political liberal. He was a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War in the 1960s and in a television interview during the early 1970s he publicly endorsed George McGovern.[256] He was unhappy about what he considered an "irrationalist" viewpoint taken by many radical political activists from the late 1960s and onwards. In his second volume of autobiography, In Joy Still Felt, Asimov recalled meeting the counterculture figure Abbie Hoffman. Asimov's impression was that the 1960s' counterculture heroes had ridden an emotional wave which, in the end, left them stranded in a "no-man's land of the spirit" from which he wondered if they would ever return.[257]

Asimov vehemently opposed Richard Nixon, considering him "a crook and a liar". He closely followed Watergate, and was pleased when the president was forced to resign. Asimov was dismayed over the pardon extended to Nixon by his successor Gerald Ford: "I was not impressed by the argument that it has spared the nation an ordeal. To my way of thinking, the ordeal was necessary to make certain it would never happen again."[258]

After Asimov's name appeared in the mid-1960s on a list of people the Communist Party USA "considered amenable" to its goals, the FBI investigated him. Because of his academic background, the bureau briefly considered Asimov as a possible candidate for known Soviet spy ROBPROF, but found nothing suspicious in his life or background.[259]

Asimov appeared to hold an equivocal attitude towards Israel. In his first autobiography, he indicates his support for the safety of Israel, though insisting that he was not a Zionist.[260] In his third autobiography, Asimov stated his opposition to the creation of a Jewish state, on the grounds that he was opposed to having nation-states in general, and supported the notion of a single humanity. Asimov especially worried about the safety of Israel given that it had been created among Muslim neighbors "who will never forgive, never forget and never go away", and said that Jews had merely created for themselves another "Jewish ghetto".[n]

Social issues

Asimov believed that "science fiction ... serve[s] the good of humanity".[162] He considered himself a feminist even before women's liberation became a widespread movement; he argued that the issue of women's rights was closely connected to that of population control.[261] Furthermore, he believed that homosexuality must be considered a "moral right" on population grounds, as must all consenting adult sexual activity that does not lead to reproduction.[261] He issued many appeals for population control, reflecting a perspective articulated by people from Thomas Malthus through Paul R. Ehrlich.[262]

In a 1988 interview by Bill Moyers, Asimov proposed computer-aided learning, where people would use computers to find information on subjects in which they were interested.[263] He thought this would make learning more interesting, since people would have the freedom to choose what to learn, and would help spread knowledge around the world. Also, the one-to-one model would let students learn at their own pace.[264] Asimov thought that people would live in space by 2019.[265]

In 1983 Asimov wrote:[266]

Computerization will undoubtedly continue onward inevitably... This means that a vast change in the nature of education must take place, and entire populations must be made "computer-literate" and must be taught to deal with a "high-tech" world.

He continues on education:

Education, which must be revolutionized in the new world, will be revolutionized by the very agency that requires the revolution — the computer.

Schools will undoubtedly still exist, but a good schoolteacher can do no better than to inspire curiosity which an interested student can then satisfy at home at the console of his computer outlet.

There will be an opportunity finally for every youngster, and indeed, every person, to learn what he or she wants to learn, in his or her own time, at his or her own speed, in his or her own way.

Education will become fun because it will bubble up from within and not be forced in from without.

Sexual harassment

Asimov would often fondle, kiss and pinch women at conventions and elsewhere without regard for their consent. According to Alec Nevala-Lee, author of an Asimov biography[267] and writer on the history of science fiction, he often defended himself by saying that far from showing objections, these women cooperated.[268] In a 1971 satirical piece, The Sensuous Dirty Old Man, Asimov wrote: "The question then is not whether or not a girl should be touched. The question is merely where, when, and how she should be touched."[268]

According to Nevala-Lee, however, "many of these encounters were clearly nonconsensual."[268] He wrote that Asimov's behavior, as a leading science-fiction author and personality, contributed to an undesirable atmosphere for women in the male-dominated science fiction community. In support of this, he quoted some of Asimov's contemporary fellow-authors such as Judith Merril, Harlan Ellison and Frederik Pohl, as well as editors such as Timothy Seldes.[268] Additional specific incidents were reported by other people including Edward L. Ferman, long-time editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, who wrote "...instead of shaking my date's hand, he shook her left breast".[269]

Environment and population

Asimov's defense of civil applications of nuclear power, even after the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant incident, damaged his relations with some of his fellow liberals. In a letter reprinted in Yours, Isaac Asimov,[261] he states that although he would prefer living in "no danger whatsoever" to living near a nuclear reactor, he would still prefer a home near a nuclear power plant to a slum on Love Canal or near "a Union Carbide plant producing methyl isocyanate", the latter being a reference to the Bhopal disaster.[261]

In the closing years of his life, Asimov blamed the deterioration of the quality of life that he perceived in New York City on the shrinking tax base caused by the middle-class flight to the suburbs, though he continued to support high taxes on the middle class to pay for social programs. His last nonfiction book, Our Angry Earth (1991, co-written with his long-time friend, science fiction author Frederik Pohl), deals with elements of the environmental crisis such as overpopulation, oil dependence, war, global warming, and the destruction of the ozone layer.[270][271] In response to being presented by Bill Moyers with the question "What do you see happening to the idea of dignity to human species if this population growth continues at its present rate?", Asimov responded:

It's going to destroy it all ... if you have 20 people in the apartment and two bathrooms, no matter how much every person believes in freedom of the bathroom, there is no such thing. You have to set up, you have to set up times for each person, you have to bang at the door, aren't you through yet, and so on. And in the same way, democracy cannot survive overpopulation. Human dignity cannot survive it. Convenience and decency cannot survive it. As you put more and more people onto the world, the value of life not only declines, but it disappears.[272]

Other authors

Asimov enjoyed the writings of J. R. R. Tolkien, and used The Lord of the Rings as a plot point in a Black Widowers story, titled Nothing like Murder.[273] In the essay "All or Nothing" (for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Jan 1981), Asimov said that he admired Tolkien and that he had read The Lord of the Rings five times. (The feelings were mutual, with Tolkien saying that he had enjoyed Asimov's science fiction.[274] This would make Asimov an exception to Tolkien's earlier claim[274] that he rarely found "any modern books" that were interesting to him.)

He acknowledged other writers as superior to himself in talent, saying of Harlan Ellison, "He is (in my opinion) one of the best writers in the world, far more skilled at the art than I am."[275] Asimov disapproved of the New Wave's growing influence, stating in 1967 "I want science fiction. I think science fiction isn't really science fiction if it lacks science. And I think the better and truer the science, the better and truer the science fiction".[162]

The feelings of friendship and respect between Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were demonstrated by the so-called "Clarke–Asimov Treaty of Park Avenue", negotiated as they shared a cab in New York. This stated that Asimov was required to insist that Clarke was the best science fiction writer in the world (reserving second-best for himself), while Clarke was required to insist that Asimov was the best science writer in the world (reserving second-best for himself). Thus, the dedication in Clarke's book Report on Planet Three (1972) reads: "In accordance with the terms of the Clarke–Asimov treaty, the second-best science writer dedicates this book to the second-best science-fiction writer."

In 1980, Asimov wrote a highly critical review of George Orwell's 1984.[276] Though dismissive of his attacks, James Machell has stated that they "are easier to understand when you consider that Asimov viewed 1984 as dangerous literature. He opines that if communism were to spread across the globe, it would come in a completely different form to the one in 1984, and by looking to Orwell as an authority on totalitarianism, 'we will be defending ourselves against assaults from the wrong direction and we will lose'."[277]

Asimov became a fan of mystery stories at the same time as science fiction. He preferred to read the former because "I read every [science fiction] story keenly aware that it might be worse than mine, in which case I had no patience with it, or that it might be better, in which case I felt miserable".[146] Asimov wrote "I make no secret of the fact that in my mysteries I use Agatha Christie as my model. In my opinion, her mysteries are the best ever written, far better than the Sherlock Holmes stories, and Hercule Poirot is the best detective fiction has seen. Why should I not use as my model what I consider the best?"[278] He enjoyed Sherlock Holmes, but considered Arthur Conan Doyle to be "a slapdash and sloppy writer."[279]

Asimov also enjoyed humorous stories, particularly those of P. G. Wodehouse.[280]

In non-fiction writing, Asimov particularly admired the writing style of Martin Gardner, and tried to emulate it in his own science books. On meeting Gardner for the first time in 1965, Asimov told him this, to which Gardner answered that he had based his own style on Asimov's.[281]

Remove ads

Influence

Summarize

Perspective

Paul Krugman, holder of a Nobel Prize in Economics, stated Asimov's concept of psychohistory inspired him to become an economist.[282]

John Jenkins, who has reviewed the vast majority of Asimov's written output, once observed, "It has been pointed out that most science fiction writers since the 1950s have been affected by Asimov, either modeling their style on his or deliberately avoiding anything like his style."[283] Along with such figures as Bertrand Russell and Karl Popper, Asimov left his mark as one of the most distinguished interdisciplinarians of the 20th century.[284] "Few individuals", writes James L. Christian, "understood better than Isaac Asimov what synoptic thinking is all about. His almost 500 books—which he wrote as a specialist, a knowledgeable authority, or just an excited layman—range over almost all conceivable subjects: the sciences, history, literature, religion, and of course, science fiction."[285]

In 2024, DARPA named one of its programs after Asimov, inspired by his “Three Laws of Robotics.” The program, Autonomy Standards and Ideals with Military Operational Values (ASIMOV), aims to develop benchmarks objectively and quantitatively assessing the ethical challenges and readiness of utilizing autonomous systems for military operations.[286]

Remove ads

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

Over a space of 40 years, I published an average of 1,000 words a day. Over the space of the second 20 years, I published an average of 1,700 words a day.

— Asimov, 1994[287]

Depending on the counting convention used,[288] and including all titles, charts, and edited collections, there may be currently over 500 books in Asimov's bibliography—as well as his individual short stories, individual essays, and criticism. For his 100th, 200th, and 300th books (based on his personal count), Asimov published Opus 100 (1969), Opus 200 (1979), and Opus 300 (1984), celebrating his writing.[193][194][195] An extensive bibliography of Isaac Asimov's works has been compiled by Ed Seiler.[289] His book writing rate was analysed, showing that he wrote faster as he wrote more.[290]

An online exhibit in West Virginia University Libraries' virtually complete Asimov Collection displays features, visuals, and descriptions of some of his more than 600 books, games, audio recordings, videos, and wall charts. Many first, rare, and autographed editions are in the Libraries' Rare Book Room. Book jackets and autographs are presented online along with descriptions and images of children's books, science fiction art, multimedia, and other materials in the collection.[291][292]

Science fiction

"Greater Foundation" series

The Robot series was originally separate from the Foundation series. The Galactic Empire novels were published as independent stories, set earlier in the same future as Foundation. Later in life, Asimov synthesized the Robot series into a single coherent "history" that appeared in the extension of the Foundation series.[293]

All of these books were published by Doubleday & Co, except the original Foundation trilogy which was originally published by Gnome Books before being bought and republished by Doubleday.

- The Robot series:

- The Caves of Steel. 1954. ISBN 0-553-29340-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (first Elijah Baley SF-crime novel) - The Naked Sun. 1957. ISBN 0-553-29339-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (second Elijah Baley SF-crime novel) - The Robots of Dawn. 1983. ISBN 0-553-29949-2. (third Elijah Baley SF-crime novel)

- Robots and Empire. 1985. ISBN 978-0-586-06200-5. (sequel to the Elijah Baley trilogy)

- The Caves of Steel. 1954. ISBN 0-553-29340-0.

- Galactic Empire novels:

- Pebble in the Sky. 1950. ISBN 0-553-29342-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (early Galactic Empire) - The Stars, Like Dust. 1951. ISBN 0-553-29343-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (long before the Empire) - The Currents of Space. 1952. ISBN 0-553-29341-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (Republic of Trantor still expanding)

- Pebble in the Sky. 1950. ISBN 0-553-29342-7.

- Foundation prequels:

- Prelude to Foundation. 1988. ISBN 0-553-27839-8.

- Forward the Foundation. 1993. ISBN 0-553-40488-1.

- Original Foundation trilogy:

- Foundation. 1951. ISBN 0-553-29335-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Foundation and Empire. 1952. ISBN 0-553-29337-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (also published with the title 'The Man Who Upset the Universe' as a 35¢ Ace paperback, D-125, in about 1952) - Second Foundation. 1953. ISBN 0-553-29336-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

- Foundation. 1951. ISBN 0-553-29335-4.

- Extended Foundation series:

- Foundation's Edge. 1982. ISBN 0-553-29338-9.

- Foundation and Earth. 1986. ISBN 0-553-58757-9.

Lucky Starr series (as Paul French)

All published by Doubleday & Co

Norby Chronicles (with Janet Asimov)

All published by Walker & Company

- Norby, the Mixed-Up Robot (1983)

- Norby's Other Secret (1984)

- Norby and the Lost Princess (1985)

- Norby and the Invaders (1985)

- Norby and the Queen's Necklace (1986)

- Norby Finds a Villain (1987)

- Norby Down to Earth (1988)

- Norby and Yobo's Great Adventure (1989)

- Norby and the Oldest Dragon (1990)

- Norby and the Court Jester (1991)

Novels not part of a series

Novels marked with an asterisk (*) have minor connections to Foundation universe.

- The End of Eternity (1955), Doubleday (*)

- Fantastic Voyage (1966), Bantam Books (paperback) and Houghton Mifflin (hardback) (a novelization of the movie)

- The Gods Themselves (1972), Doubleday

- Fantastic Voyage II: Destination Brain (1987), Doubleday (not a sequel to Fantastic Voyage, but a similar, independent story)

- Nemesis (1989), Bantam Doubleday Dell (*)

- Nightfall (1990), Doubleday, with Robert Silverberg (based on "Nightfall", a 1941 short story written by Asimov)

- Child of Time (1992), Bantam Doubleday Dell, with Robert Silverberg (based on "The Ugly Little Boy", a 1958 short story written by Asimov)

- The Positronic Man (1992), Bantam Doubleday Dell, with Robert Silverberg (*) (based on The Bicentennial Man, a 1976 novella written by Asimov)

Short-story collections

- I, Robot. Gnome Books initially, later Doubleday & Co. 1950. ISBN 0-553-29438-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - The Martian Way and Other Stories. Doubleday. 1955. ISBN 0-8376-0463-X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Earth Is Room Enough. Doubleday. 1957. ISBN 0-449-24125-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Nine Tomorrows. Doubleday. 1959. ISBN 0-449-24084-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - The Rest of the Robots. Doubleday. 1964. ISBN 0-385-09041-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Through a Glass, Clearly. New English Library. 1967. ISBN 0-86025-124-1.

- Asimov's Mysteries. Doubleday. 1968.

- Nightfall and Other Stories. Doubleday. 1969. ISBN 0-449-01969-1.

- The Early Asimov. Doubleday. 1972. ISBN 0-449-02850-X.

- The Best of Isaac Asimov. Sphere. 1973. ISBN 0-7221-1256-4.

- Buy Jupiter and Other Stories. Doubleday. 1975. ISBN 0-385-05077-1.

- The Bicentennial Man and Other Stories. Doubleday. 1976. ISBN 0-575-02240-X.

- The Complete Robot. Doubleday. 1982.

- The Winds of Change and Other Stories. Doubleday. 1983. ISBN 0-385-18099-3.

- The Edge of Tomorrow. Tor. 1985. ISBN 0-312-93200-6.

- The Alternate Asimovs. Doubleday. 1986. ISBN 0-385-19784-5.

- The Best Science Fiction of Isaac Asimov. Doubleday. 1986.

- Robot Dreams. Byron Preiss. 1986. ISBN 0-441-73154-6.

- Azazel. Doubleday. 1988.

- Robot Visions. Byron Preiss. 1990. ISBN 0-451-45064-7.

- Gold. Harper Prism. 1995. ISBN 0-553-28339-1.

- Magic. Harper Prism. 1996. ISBN 0-00-224622-8.

Mysteries

Novels

- The Death Dealers (1958), Avon Books, republished as A Whiff of Death by Walker & Company

- Murder at the ABA (1976), Doubleday, also published as Authorized Murder

Short-story collections

Black Widowers series

- Tales of the Black Widowers (1974), Doubleday

- More Tales of the Black Widowers (1976), Doubleday

- Casebook of the Black Widowers (1980), Doubleday

- Banquets of the Black Widowers (1984), Doubleday

- Puzzles of the Black Widowers (1990), Doubleday

- The Return of the Black Widowers (2003), Carroll & Graf

Other mysteries

- Asimov's Mysteries (1968), Doubleday

- The Key Word and Other Mysteries (1977), Walker

- The Union Club Mysteries (1983), Doubleday

- The Disappearing Man and Other Mysteries (1985), Walker

- The Best Mysteries of Isaac Asimov (1986), Doubleday