Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Kashmiri language

Indo-Aryan language spoken in Kashmir From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

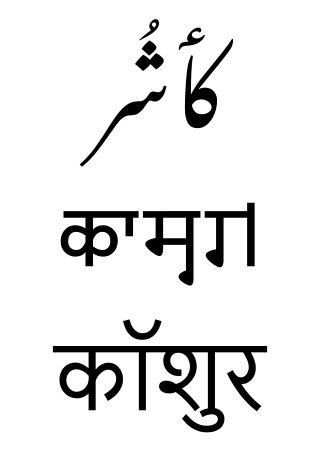

Kashmiri (English: /kæʃˈmɪəri/ kash-MEER-ee),[13] also known by its endonym Koshur[14] (Kashmiri: کٲشُر (Perso-Arabic, Official Script), pronounced [kəːʃur]),[1] is an Indo-Aryan language of the Dardic branch spoken by around 7 million Kashmiris of the Kashmir region,[15] primarily in the Kashmir Valley and surrounding hills of the Indian-administrated union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, over half the population of that territory.[16] Kashmiri has split ergativity and the unusual verb-second word order.

Since 2020, it has been made an official language of Jammu and Kashmir along with Dogri, Hindi, Urdu and English.[17] Kashmiri is also among the 22 scheduled languages of India.

Kashmiri is spoken by roughly five percent of Pakistani-administrated Azad Kashmir's population.[18]

Remove ads

Geographic distribution and status

Summarize

Perspective

There are about 6.8 million speakers of Kashmiri and related dialects in Jammu and Kashmir and amongst the Kashmiri diaspora in other states of India.[19] Most Kashmiri speakers are located in the Kashmir Valley and other surrounding areas of Jammu and Kashmir.[20] In the Kashmir Valley, Kashmiri speakers form the majority.

The Kashmiri language is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India.[21] It was a part of the Eighth Schedule in the former constitution of Jammu and Kashmir. Along with other regional languages mentioned in the Sixth Schedule, as well as Hindi and Urdu, the Kashmiri language was to be developed in the state.[22] After Hindi, Kashmiri is the second fastest growing language of India, followed by Meitei (Manipuri) as well as Gujarati in the third place, and Bengali in the fourth place, according to the 2011 census of India.[23]

Persian began to be used as the court language in Kashmir during the 14th centuries, under the influence of Islam. It was replaced by Urdu in 1889 during the Dogra rule.[24][25] In 2020, Kashmiri became an official language in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir for the first time.[26][27][28] Poguli and Kishtwari are closely related to Kashmiri, which are spoken in the mountains to the south of the Kashmir Valley and have sometimes been counted as dialects of Kashmiri.

Kashmiri is spoken by roughly five percent of Azad Kashmir's population.[18] According to the 1998 Pakistan Census, there were 132,450 Kashmiri speakers in Azad Kashmir.[29] Native speakers of the language were dispersed in "pockets" throughout Azad Kashmir,[30][31] particularly in the districts of Muzaffarabad (15%), Neelam (20%) and Hattian (15%), with very small minorities in Haveli (5%) and Bagh (2%).[29] The Kashmiri spoken in Muzaffarabad is distinct from, although still intelligible with, the Kashmiri of the Neelam Valley to the north.[31] In Neelam Valley, Kashmiri is the second most widely spoken language and the majority language in at least a dozen or so villages, where in about half of these, it is the sole mother tongue.[31] The Kashmiri dialect of Neelum is closer to the variety spoken in northern Kashmir Valley, particularly Kupwara.[31] At the 2017 Census of Pakistan, as many as 350,000 people declared their first language to be Kashmiri.[32][33]

A process of language shift is observable among Kashmiri-speakers in Azad Kashmir according to linguist Tariq Rahman, as they gradually adopt local languages such as Pahari-Pothwari, Hindko or move towards the lingua franca Urdu.[34][30][35][31] This has resulted in these languages gaining ground at the expense of Kashmiri.[36][37] There have been calls for the promotion of Kashmiri at an official level; in 1983, a Kashmiri Language Committee was set up by the government to patronise Kashmiri and impart it in school-level education. However, the limited attempts at introducing the language have not been successful, and it is Urdu, rather than Kashmiri, that Kashmiri Muslims of Azad Kashmir have seen as their identity symbol.[38] Rahman notes that efforts to organise a Kashmiri language movement have been challenged by the scattered nature of the Kashmiri-speaking community in Azad Kashmir.[38]

Remove ads

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

Kashmiri has a very large phoneme inventory: 32 vowels and 62 consonants, giving that vowel nasalization and consonant palatalization are phonemic and not phonetic.[39] It has the following phonemes.[40][41]

Vowels

The oral vowels are as follows:

The short high vowels are near-high, and the low vowels apart from /aː/ are near-low.

Nasalization is phonemic. All sixteen oral vowels have nasal counterparts.

Consonants

Palatalization is phonemic. All consonants apart from those in the post-alveolar/palatal column have palatalized counterparts.

Archaisms

Kashmiri, as also the other Dardic languages, shows important divergences from the Indo-Aryan mainstream. One is the partial maintenance of the three sibilant consonants s ṣ ś of the Old Indo-Aryan period. For another example, the prefixing form of the number 'two', which is found in Sanskrit as dvi-, has developed into ba-/bi- in most other Indo-Aryan languages, but du- in Kashmiri (preserving the original dental stop d). Seventy-two is dusatath in Kashmiri, bahattar in Hindi-Urdu and Punjabi, and dvisaptati in Sanskrit.[42]

Certain features in Kashmiri even appear to stem from Indo-Aryan even predating the Vedic period. For instance, there was an /s/ > /h/ consonant shift in some words that had already occurred with Vedic Sanskrit (This tendency was complete in the Iranian branch of Indo-Iranian), yet is lacking in Kashmiri equivalents. The word rahit in Vedic Sanskrit and modern Hindi (meaning 'excluding' or 'without') corresponds to rost in Kashmiri. Similarly, sahit (meaning 'including' or 'with') corresponds to sost in Kashmiri.[42]

Remove ads

Writing system

Summarize

Perspective

There are three orthographical systems used to write the Kashmiri language: the Perso-Arabic script, the Devanagari script and the Sharada script. The Roman script is also sometimes informally used to write Kashmiri, especially online.[4]

The Kashmiri language was traditionally written in the Sharada script from the 8th Century AD onwards.[43] Between the 8th and the first quarter of the 20th century AD, Sharada was the primary script of inscriptional and literary production in Kashmir for Sanskrit and Kashmiri.[44] With increased use of Persian script for writing Kashmiri in the 19th century AD, and the growth of other brahmic scripts such as Devanagari and Takri, the use of Sharada declined.[44] The Sharada script is inadequate for writing modern Kashmiri because it lacks sufficient signs to represent Kashmiri vowels.[44] Modern usage of Sharada is limited to religious ceremonies and rituals of Kashmiri Pandits, and for horoscope-writing by them.[45][44]

Today Kashmiri is primarily written in Perso-Arabic (with some modifications, such as additions of new signs to represent Kashmiri vowels).[46][44] Among languages written in the Perso-Arabic script, Kashmiri is one of the scripts that regularly indicates all vowel sounds.[47]

The Kashmiri Perso-Arabic script is recognized as the official script of Kashmiri language by the Jammu and Kashmir government and the Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Languages.[48][49][50][51] The Kashmiri Perso-Arabic script has been derived from Persian alphabet. The consonant inventory and their corresponding pronunciations of Kashmiri Perso-Arabic script doesn't differ from Perso-Arabic script, with the exception of the letter ژ, which is pronounced as /t͡s/ instead of /ʒ/. However, the vowel inventory of Kashmiri is significantly larger than other Perso-Arabic derived or influenced South Asian Perso-Arabic scripts. There are 17 vowels in Kashmiri, shown with diacritics, letters (alif, waw, ye), or both. In Kashmiri, the convention is that most vowel diacritics are written at all times.

Despite Kashmiri Perso-Arabic script cutting across religious boundaries and being used by both the Kashmiri Hindus and the Kashmiri Muslims,[52] some attempts have been made to give a religious outlook regarding the script and make Kashmiri Perso-Arabic script to be associated with Kashmiri Muslims, while the Kashmiri Devanagari script to be associated with some sections of Kashmiri Hindu community.[53][54][55]

Perso-Arabic script

Consonants

Vowels

Devanagari

Consonants

Vowels

There have been a few versions of the Devanagari script for Kashmiri.[59] The 2002 version of the proposal is shown below.[60] This version has readers and more content available on the Internet, even though this is an older proposal.[61][62] This version makes use of the vowels ॲ/ऑ and vowel signs कॅ/कॉ for the schwa-like vowel [ə] and elongated schwa-like vowel [əː] that also exist in other Devanagari-based scripts such as Marathi and Hindi but are used for the sound of other vowels.

Tabulated below is the latest (2009) version of the proposal to spell the Kashmiri vowels with Devanagari.[63][64] The primary change in this version is the changed stand alone characters ॳ / ॴ and vowel signs कऺ / कऻ for the schwa-like vowel [ə] & elongated schwa-like vowel [əː] and a new stand alone vowel ॵ and vowel sign कॏ for the open-mid back rounded vowel [ɔ] which can be used instead of the consonant व standing-in for this vowel.

Sharada script

Consonants

Vowels

Vowel mark

Remove ads

Grammar

Summarize

Perspective

Kashmiri is a fusional language[68] with verb-second (V2) word order.[69] Several of Kashmiri's grammatical features distinguish it from other Indo-Aryan languages.[70]

Nouns

Kashmiri nouns are inflected according to gender, number and case. There are no articles, nor is there any grammatical distinction for definiteness, although there is some optional adverbial marking for indefinite or "generic" noun qualities.[68]

Gender

The Kashmiri gender system is divided into masculine and feminine. Feminine forms are typically generated by the addition of a suffix (or in most cases, a morphophonemic change, or both) to a masculine noun.[68] A relatively small group of feminine nouns have unique suppletion forms that are totally different from the corresponding masculine forms.[71] The following table illustrates the range of possible gender forms:[72]

Some nouns borrowed from other languages, such as Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, Urdu or English, follow a slightly different gender system. Notably, many words borrowed from Urdu have different genders in Kashmiri.[71]

Case

There are five cases in Kashmiri: nominative, dative, ergative, ablative and vocative.[73] Case is expressed via suffixation of the noun.

Kashmiri utilizes an ergative-absolutive case structure when the verb is in past simple tense.[73] Thus, in these sentences, the subject of a transitive verb is marked in the ergative case and the object in nominative, which is identical to how the subject of an intransitive verb is marked.[73][74][75] However, in sentences constructed in any other tense, or in past tense sentences with intransitive verbs, a nominative-dative paradigm is adopted, with objects (whether direct or indirect) generally marked in dative case.[76] Other case distinctions, such as locative, instrumental, genitive, comitative and allative, are marked by postpositions rather than suffixation.[77]

Noun morphology

The following table illustrates Kashmiri noun declension according to gender, number and case.[76][78]

Verbs

Kashmiri verbs are declined according to tense and person, and to a lesser extent, gender. Tense, along with certain distinctions of aspect, is formed by the addition of suffixes to the verb stem (minus the infinitive ending - /un/), and in many cases by the addition of various modal auxiliaries.[79] Postpositions fulfill numerous adverbial and semantic roles.[80]

Tense

Present tense in Kashmiri is an auxiliary construction formed by a combination of the copula and the imperfective suffix -/aːn/ added to the verb stem. The various copula forms agree with their subject according to gender and number, and are provided below with the verb /jun/ (to come):[81]

Past tense in Kashmiri is significantly more complex than the other tenses, and is subdivided into three past tense distinctions.[82] The past simple (sometimes called past proximate) refers to completed past actions. Past remote refers to actions that lack this in-built perfective aspect. Past indefinite refers to actions performed a long time ago, and is often used in historical narrative or storytelling contexts.[83]

As described above, Kashmiri is a split-ergative language; in all three of these past tense forms, the subjects of transitive verbs are marked in the ergative case and direct objects in the nominative. Intransitive subjects are marked in the nominative.[83] Nominative arguments, whether subjects or objects, dictate gender, number and person marking on the verb.[83][84]

Verbs of the past simple tense are formed via the addition of a suffix to the verb stem, which usually undergoes certain uniform morphophonemic changes. First and third person verbs of this type do not take suffixes and agree with the nominative object in gender and number, but there are second person verb endings. The entire past simple tense paradigm of transitive verbs is illustrated below using the verb /parun/ ("to read"):[85]

A group of irregular intransitive verbs (special intransitives), take a different set of endings in addition to the morphophonemic changes that affect most past tense verbs.[86]

Intransitive verbs in the past simple are conjugated the same as intransitives in the past indefinite tense form.[87]

In contrast to the Past simple, verb stems are unchanged in the past indefinite and past remote, although the addition of the tense suffixes does cause some morphophonetic change.[88] Transitive verbs are declined according to the following paradigm:[89]

As in the past simple, "special intransitive" verbs take a different set of endings in the past indefinite and past remote:[90]

Regular intransitive verbs also take a different set of endings in the past indefinite and past remote, subject to some morphophonetic variation:[91]

Future tense intransitive verbs are formed by the addition of suffixes to the verb stem:[92]

The future tense of transitive verbs, however, is formed by adding suffixes that agree with both the subject and direct object according to number, in a complex fashion:[93]

Aspect

There are two main aspectual distinctions in Kashmiri, perfective and imperfective. Both employ a participle formed by the addition of a suffix to the verb stem, as well as the fully conjugated auxiliary /aːsun/ ("to be")—which agrees according to gender, number and person with the object (for transitive verbs) or the subject (for intransitive verbs).[94]

Like the auxiliary, the participle suffix used with the perfective aspect (expressing completed or concluded action) agrees in gender and number with the object (for transitive verbs) or subject (for intransitives) as illustrated below:[94]

The imperfective (expressing habitual or progressive action) is simpler, taking the participle suffix -/aːn/ in all forms, with only the auxiliary showing agreement.[95] A type of iterative aspect can be expressed by reduplicating the imperfective participle.[96]

Pronouns

Pronouns are declined according to person, gender, number and case, although only third person pronouns are overtly gendered. Also in third person, a distinction is made between three degrees of proximity, called proximate, remote I and remote II.[97]

There is also a dedicated genitive pronoun set, in contrast to the way that the genitive is constructed adverbially elsewhere. As with future tense, these forms agree with both the subject and direct object in person and number.[98]

Adjectives

There are two kinds of adjectives in Kashmiri, those that agree with their referent noun (according to case, gender and number) and those that are not declined at all.[99] Most adjectives are declined, and generally take the same endings and gender-specific stem changes as nouns.[100] The declinable adjective endings are provided in the table below, using the adjective وۄزُل [ʋɔzul] ("red"):[101][102]

Among those adjectives not declined are adjectives that end in -[lad̪] or -[ɨ], adjectives borrowed from other languages, and a few isolated irregulars.[101]

The comparative and superlative forms of adjectives are formed with the words ژۆر [t͡sor] ("more") and سؠٹھا [sʲaʈʰaː] ("most"), respectively.[103]

Numerals

Within the Kashmir language, numerals are separated into cardinal numbers and ordinal numbers.[104] These numeral forms, as well as their aggregative (both, all the five, etc.), multiplicative (two times, four times, etc.), and emphatic forms (only one, only three, etc.) are provided by the table below.[104]

The ordinal number "1st" which is [ǝkʲum] أکیُٛم for its masculine gender and [ǝkim] أکِم for its feminine gender is also known as [ɡɔɖnʲuk] گۄڈنیُٛک and [ɡɔɖnit͡ʃ] گۄڈنِچ respectively.[105]Cardinal Ordinal Aggregative Multiplicative Emphatic Suffix -[jum] for masculine -[im] for feminine -[ʋaj] -[ɡun] or -[ɡon] for masculine -[ɡɨn] for feminine -[j] 0. [sifar] صِفَر 1. [akʰ] اَکھ [ǝkʲum] or [ǝkim] أکیُٛم or أکِم [oɡun] or [oɡɨn] اۆگُن or اۆگٕن [akuj] اَکُے 2. [zɨ] زٕ [dojum] or [dojim] دۆیُم or دۆیِم [dɔʃʋaj] دۄشوَے [doɡun] or [doɡɨn] دۆگُن or دۆگٕن [zɨj] زٕے 3. [tre] ترٛےٚ [trejum] or [trejim] ترٛیٚیُم or ترٛیٚیِم [treʃʋaj] ترٛیٚشوَے [troɡun] or [troɡɨn] ترٛۆگُن or ترٛۆگٕن [trej] ترٛیٚے 4. [t͡soːr] ژور [t͡suːrʲum] or [t͡suːrim] ژوٗریُٛم or ژوٗرِم [t͡sɔʃʋaj] ژۄشوَے [t͡soɡun] or [t͡soɡɨn] ژۆگُن or ژۆگٕن [t͡soːraj] ژورَے 5. [pãːt͡sʰ] or [pə̃ːt͡sʰ] پانٛژھ or پٲنٛژھ [pɨ̃:t͡sjum] or [pɨ̃:t͡sim] پٟنٛژیُٛم or پٟنٛژِم [pãːt͡sɨʋaj] پانٛژٕوَے [pãːt͡sɨɡun] or [pãːt͡sɨɡɨn] پانٛژٕگُن or پانٛژٕگٕن [pãːt͡saj] پانٛژَے 6. [ʃe] شےٚ [ʃejum] or [ʃejim] شیٚیُم or شیٚیِم [ʃenɨʋaj] شیٚنہٕ وَے [ʃuɡun] or [ʃuɡɨn] شُگُن or شُگٕن [ʃej] شیٚے 7. [satʰ] سَتھ [sətjum] or [sətim] سٔتیُٛم or سٔتِم [satɨʋaj] سَتہٕ وَے [satɨɡun] or [satɨɡɨn] سَتہٕ گُن or سَتہٕ گٕن [sataj] سَتَے 8. [əːʈʰ] ٲٹھ [ɨːʈʰjum] or [uːʈʰjum] اٟٹھیُٛم or اوٗٹھیُٛم [ɨːʈʰim] or [uːʈʰim] اٟٹھِم or اوٗٹھِم [əːʈʰɨʋaj] ٲٹھٕ وَے [əːʈʰɨɡun] or [əːʈʰɨɡɨn] ٲٹھٕ گُن or ٲٹھٕ گٕن [əːʈʰaj] ٲٹھَے 9. [naʋ] نَو [nəʋjum] or [nəʋim] نٔویُٛم or نٔوِم [naʋɨʋaj] نَوٕوَے [naʋɨɡun] or [naʋɨɡɨn] نَوٕگُن or نَوٕگٕن [naʋaj] نَوَے 10. [dəh] or [daːh] دٔہ or داہ [dəhjum] or [dəhim] دٔہیُٛم or دٔہِم [dəhɨʋaj] دٔہہٕ وَے [dəhɨɡon] or [dəhɨɡɨn] دٔہہٕ گۆن or دٔہہٕ گٕن [dəhaj] دٔہَے 11. [kah] or [kaːh] کَہہ or کاہ [kəhjum] or [kəhim] کٔہیُٛم or کٔہِم 12. [bah] or [baːh] بَہہ or باہ [bəhjum] or [bəhim] بٔہیُٛم or بٔہِم 13. [truʋaːh] ترُٛواہ [truʋəːhjum] or [truʋəːhim] ترُٛوٲہیُٛم or ترُٛوٲہِم 14. [t͡sɔdaːh] ژۄداہ [t͡sɔdəːhjum] or [t͡sɔdəːhim] ژۄدٲہیُٛم or ژۄدٲہِم 15. [pandaːh] پَنٛداہ [pandəːhjum] or [pandəːhim] پَنٛدٲہیُٛم or پَنٛدٲہِم 16. [ʃuraːh] شُراہ [ʃurəːhjum] or [ʃurəːhim] شُرٲہیُٛم or شُرٲہِم 17. [sadaːh] سَداہ [sadəːhjum] or [sadəːhim] سَدٲہیُٛم or سَدٲہِم 18. [arɨdaːh] اَرٕداہ [arɨdəːhjum] or [arɨdəːhim] اَرٕدٲہیُٛم or اَرٕدٲہِم 19. [kunɨʋuh] کُنہٕ وُہ [kunɨʋuhjum] or [kunɨʋuhim] کُنہٕ وُہیُٛم or کُنہٕ وُہِم 20. [ʋuh] وُہ [ʋuhjum] or [ʋuhim] وُہیُٛم or وُہِم 21. [akɨʋuh] اَکہٕ وُہ [akɨʋuhjum] or [akɨʋuhim] اَکہٕ وُہیُٛم or اَکہٕ وُہِم 22. [zɨtoːʋuh] زٕتووُہ [zɨtoːʋuhjum] or [zɨtoːʋuhim] زٕتووُہیُٛم or زٕتووُہِم 23. [troʋuh] ترٛۆوُہ [troʋuhjum] or [troʋuhim] ترٛۆوُہیُٛم or ترٛۆوُہِم 24. [t͡soʋuh] ژۆوُہ [t͡soʋuhjum] or [t͡soʋuhim] ژۆوُہیُٛم or ژۆوُہِم 25. [pɨnt͡sɨh] پٕنٛژٕہ [pɨnt͡sɨhjum] or [pɨnt͡sɨhim] پٕنٛژٕہیُٛم or پٕنٛژٕہِم 26. [ʃatɨʋuh] شَتہٕ وُہ [ʃatɨʋuhjum] or [ʃatɨʋuhim] شَتہٕ وُہیُٛم or شَتہٕ وُہِم 27. [satoːʋuh] سَتووُہ [satoːʋuhjum] or [satoːʋuhim] سَتووُہیُٛم or سَتووُہِم 28. [aʈʰoːʋuh] اَٹھووُہ [aʈʰoːʋuhjum] or [aʈʰoːʋuhim] اَٹھووُہیُٛم or اَٹھووُہِم 29. [kunɨtrɨh] کُنہٕ ترٕٛہ [kunɨtrɨhjum] or [kunɨtrɨhim] کُنہٕ ترٕٛہیُٛم or کُنہٕ ترٕٛہِم 30. [trɨh] ترٕٛہ [trɨhjum] or [trɨhim] ترٕٛہیُٛم or ترٕٛہِم 31. [akɨtrɨh] اَکہٕ ترٕٛہ [akɨtrɨhjum] or [akɨtrɨhim] اَکہٕ ترٕٛہیُٛم or اَکہٕ ترٕٛہِم 32. [dɔjitrɨh] دۄیہِ ترٕٛہ [dɔjitrɨhjum] or [dɔjitrɨhjim] دۄیہِ ترٕٛہیُٛم or دۄیہِ ترٕٛہِم 33. [tejitrɨh] تیٚیہِ ترٕٛہ [tejitrɨhjum] or [tejitrɨhim] تیٚیہِ ترٕٛہیُٛم or تیٚیہِ ترٕٛہِم 34. [t͡sɔjitrɨh] ژۄیہِ ترٕٛہ [t͡sɔjitrɨhjum] or [t͡sɔjitrɨhim] ژۄیہِ ترٕٛہیُٛم or ژۄیہِ ترٕٛہِم 35. [pə̃ːt͡sɨtrɨh] or [pãːt͡sɨtrɨh] پٲنٛژٕ ترٕٛہ or پانٛژٕ ترٕٛہ [pə̃ːt͡sɨtrɨhjum] or [pãːt͡sɨtrɨhjum] پٲنٛژٕ ترٕٛہیُٛم or پانٛژٕ ترٕٛہیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨtrɨhim] or [pãːt͡sɨtrɨhim] پٲنٛژٕ ترٕٛہِم or پانٛژٕ ترٕٛہِم 36. [ʃejitrɨh] شیٚیہِ ترٕٛہ [ʃejitrɨhjum] or [ʃejitrɨhim] شیٚیہِ ترٕٛہیُٛم or شیٚیہِ ترٕٛہِم 37. [satɨtrɨh] سَتہٕ ترٕٛہ [satɨtrɨhjum] or [satɨtrɨhim] سَتہٕ ترٕٛہیُٛم or سَتہٕ ترٕٛہِم 38. [arɨtrɨh] اَرٕترٕٛہ [arɨtrɨhjum] or [arɨtrɨhim] اَرٕترٕٛہیُٛم or اَرٕترٕٛہِم 39. [kunɨtəːd͡ʒih] or [kunɨtəːd͡ʒiː] کُنہٕ تٲجِہہ or کُنہٕ تٲجی [kunɨtəːd͡ʒihjum] or [kunɨtəːd͡ʒihim] کُنہٕ تٲجِہیُٛم or کُنہٕ تٲجِہِم 40. [t͡satd͡ʒih] or [t͡satd͡ʒiː] ژَتجِہہ or ژَتجی [t͡satd͡ʒihjum] or [t͡satd͡ʒihim] ژَتجِہیُٛم or ژَتجِہِم 41. [akɨtəːd͡ʒih] or [akɨtəːd͡ʒiː] اَکہٕ تٲجِہہ or اَکہٕ تٲجی [akɨtəːd͡ʒihjum] or [akɨtəːd͡ʒihim] اَکہٕ تٲجِہیُٛم or اَکہٕ تٲجِہِم 42. [dɔjitəːd͡ʒih] or [dɔjitəːd͡ʒiː] دۄیہِ تٲجِہہ or دۄیہِ تٲجی [dɔjitəːd͡ʒihjum] or [dɔjitəːd͡ʒihim] دۄیہِ تٲجِہیُٛم or دۄیہِ تٲجِہِم 43. [tejitəːd͡ʒih] or [tejitəːd͡ʒiː] تیٚیہِ تٲجِہہ or تیٚیہِ تٲجی [tejitəːd͡ʒihjum] or [tejitəːd͡ʒihim] تیٚیہِ تٲجِہیُٛم or تیٚیہِ تٲجِہِم 44. [t͡sɔjitəːd͡ʒih] or [t͡sɔjitəːd͡ʒiː] ژۄیہِ تٲجِہہ or ژۄیہِ تٲجی [t͡sɔjitəːd͡ʒihjum] or [t͡sɔjitəːd͡ʒihim] ژۄیہِ تٲجِہیُٛم or ژۄیہِ تٲجِہِم 45. [pə̃ːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒih] or [pãːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒih] or [pə̃ːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒiː] or [pãːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒiː] پٲنٛژٕ تٲجِہہ or پانٛژٕ تٲجِہہ or پٲنٛژٕ تٲجی or پانٛژٕ تٲجی [pə̃ːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒihjum] or [pãːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒihim] پٲنٛژٕ تٲجِہیُٛم or پانٛژٕ تٲجِہیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒihim] or [pãːt͡sɨtəːd͡ʒihim] پٲنٛژٕ تٲجِہِم or پانٛژٕ تٲجِہِم 46. [ʃejitəːd͡ʒih] or [ʃejitəːd͡ʒiː] شیٚیہِ تٲجِہہ or شیٚیہِ تٲجی [ʃejitəːd͡ʒihjum] or [ʃejitəːd͡ʒihim] شیٚیہِ تٲجِہیُٛم or شیٚیہِ تٲجِہِم 47. [satɨtəːd͡ʒih] or [satɨtəːd͡ʒiː] سَتہٕ تٲجِہہ or سَتہٕ تٲجی [satɨtəːd͡ʒihjum] or [satɨtəːd͡ʒihim] سَتہٕ تٲجِہیُٛم or سَتہٕ تٲجِہِم 48. [arɨtəːd͡ʒih] or [arɨtəːd͡ʒiː] اَرٕتٲجِہہ or اَرٕتٲجی [arɨtəːd͡ʒihjum] or [arɨtəːd͡ʒihim] اَرٕتٲجِہیُٛم or اَرٕتٲجِہِم 49. [kunɨʋanzaːh] کُنہٕ وَنٛزاہ [kunɨʋanzəːhjum] or [kunɨʋanzəːhim] کُنہٕ وَنٛزٲہیُٛم or کُنہٕ وَنٛزٲہِم 50. [pant͡saːh] پَنٛژاہ [pant͡səːhjum] or [pant͡səːhim] پَنٛژٲہیُٛم or پَنٛژٲہِم 51. [akɨʋanzaːh] اَکہٕ وَنٛزاہ [akɨʋanzəːhjum] or [akɨʋanzəːhim] اَکہٕ وَنٛزٲہیُٛم or اَکہٕ وَنٛزٲہِم 52. [duʋanzaːh] دُوَنٛزاہ [duʋanzəːhjum] or [duʋanzəːhim] دُوَنٛزٲہیُٛم or دُوَنٛزٲہِم 53. [truʋanzaːh] or [trɨʋanzaːh] ترُٛوَنٛزاہ or ترٕٛوَنٛزاہ [truʋanzəːhjum] or [truʋanzəːhim] ترُٛوَنٛزٲہیُٛم or ترُٛوَنٛزٲہِم [trɨʋanzəːhjum] or [trɨʋanzəːhim] ترٕٛوَنٛزٲہیُٛم or ترٕٛوَنٛزٲہِم 54. [t͡suʋanzaːh] ژُوَنٛزاہ [t͡suʋanzəːhjum] or [t͡suʋanzəːhim] ژُوَنٛزٲہیُٛم or ژُوَنٛزٲہِم 55. [pə̃ːt͡sɨʋanzaːh] or [pãːt͡sɨʋanzaːh] پٲنٛژٕ وَنٛزاہ or پانٛژٕ وَنٛزاہ [pə̃ːt͡sɨʋanzəːhjum] or [pãːt͡sɨʋanzəːhjum] پٲنٛژٕ وَنٛزٲہیُٛم or پانٛژٕ وَنٛزٲہیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨʋanzəːhim] or [pãːt͡sɨʋanzəːhim] پٲنٛژٕ وَنٛزٲہِم or پانٛژٕ وَنٛزٲہِم 56. [ʃuʋanzaːh] شُوَنٛزاہ [ʃuʋanzəːhjum] or [ʃuʋanzəːhim] شُوَنٛزٲہیُٛم or شُوَنٛزٲہِم 57. [satɨʋanzaːh] سَتہٕ وَنٛزاہ [satɨʋanzəːhjum] or [satɨʋanzəːhim] سَتہٕ وَنٛزٲہیُٛم or سَتہٕ وَنٛزٲہِم 58. [arɨʋanzaːh] اَرٕوَنٛزاہ [arɨʋanzəːhjum] or [arɨʋanzəːhim] اَرٕوَنٛزٲہیُٛم or اَرٕوَنٛزٲہِم 59. [kunɨhəːʈʰ] کُنہٕ ہٲٹھ [kunɨhəːʈʰjum] or [kunɨhəːʈʰim] کُنہٕ ہٲٹھیُٛم or کُنہٕ ہٲٹھِم 60. [ʃeːʈʰ] شیٹھ [ʃeːʈʰjum] or [ʃeːʈʰim] شیٹھیُٛم or شیٹھِم 61. [akɨhəːʈʰ] اَکہٕ ہٲٹھ [akɨhəːʈʰjum] or [akɨhəːʈʰim] اَکہٕ ہٲٹھیُٛم or اَکہٕ ہٲٹھِم 62. [duhəːʈʰ] دُ ہٲٹھ [duhəːʈʰjum] or [duhəːʈʰim] دُ ہٲٹھیُٛم or دُ ہٲٹھِم 63. [truhəːʈʰ] or [trɨhəːʈʰ] ترُٛہٲٹھ or ترٕٛہٲٹھ [truhəːʈʰjum] or [truhəːʈʰim] ترُٛہٲٹھیُٛم or ترُٛہٲٹھِم [trɨhəːʈʰjum] or [trɨhəːʈʰim] ترٕٛہٲٹھیُٛم or ترٕٛہٲٹھِم 64. [t͡suhəːʈʰ] ژُہٲٹھ [t͡suhəːʈʰjum] or [t͡suhəːʈʰim] ژُہٲٹھیُٛم or ژُہٲٹھِم 65. [pə̃ːt͡sɨhəːʈʰ] or [pãːt͡sɨhəːʈʰ] پٲنٛژٕ ہٲٹھ or پانٛژٕ ہٲٹھ [pə̃ːt͡sɨhəːʈʰjum] or [pãːt͡sɨhəːʈʰjum] پٲنٛژٕ ہٲٹھیُٛم or پانٛژٕ ہٲٹھیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨhəːʈʰim] or [pãːt͡sɨhəːʈʰim] پٲنٛژٕ ہٲٹھِم or پانٛژٕ ہٲٹھِم 66. [ʃuhəːʈʰ] شُہٲٹھ [ʃuhəːʈʰjum] or [ʃuhəːʈʰim] شُہٲٹھیُٛم or شُہٲٹھِم 67. [satɨhəːʈʰ] سَتہٕ ہٲٹھ [satɨhəːʈʰjum] or [satɨhəːʈʰim] سَتہٕ ہٲٹھیُٛم or سَتہٕ ہٲٹھِم 68. [arɨhəːʈʰ] اَرٕہٲٹھ [arɨhəːʈʰjum] or [arɨhəːʈʰim] اَرٕہٲٹھیُٛم or اَرٕہٲٹھِم 69. [kunɨsatatʰ] کُنہٕ سَتَتھ [kunɨsatatyum] or [kunɨsatatim] کُنہٕ سَتَتیُٛم or کُنہٕ سَتَتِم 70. [satatʰ] سَتَتھ [satatjum] or [satatim] سَتَتیُٛم or سَتَتِم 71. [akɨsatatʰ] اَکہٕ سَتَتھ [akɨsatatjum] or [akɨsatatim] اَکہٕ سَتَتیُٛم or اَکہٕ سَتَتِم 72. [dusatatʰ] دُسَتَتھ [dusatatjum] or [dusatatim] دُسَتَتیُٛم or دُسَتَتِم 73. [trusatatʰ] or [trɨsatatʰ] ترُٛسَتَتھ or ترٕٛسَتَتھ [trusatatjum] or [trusatatim] ترُٛسَتَتیُٛم or ترُٛسَتَتِم [trɨsatatjum] or [trɨsatatim] ترٕٛسَتَتیُٛم or ترٕٛسَتَتِم 74. [t͡susatatʰ] ژُسَتَتھ [t͡susatatjum] or [t͡susatatim] ژُسَتَتیُٛم or ژُسَتَتِم 75. [pə̃ːt͡sɨsatatʰ] or [pãːt͡sɨsatatʰ] پٲنٛژٕ سَتَتھ or پانٛژٕ سَتَتھ [pə̃ːt͡sɨsatatjum] or [pãːt͡sɨsatatjum] پٲنٛژٕ سَتَتیُٛم or پانٛژٕ سَتَتیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨsatatim] or [pãːt͡sɨsatatim] پٲنٛژٕ سَتَتِم or پانٛژٕ سَتَتِم 76. [ʃusatatʰ] شُسَتَتھ [ʃusatatjum] or [ʃusatatim] شُسَتَتیُٛم or شُسَتَتِم 77. [satɨsatatʰ] سَتہٕ سَتَتھ [satɨsatatjum] or [satɨsatatim] سَتہٕ سَتَتیُٛم or سَتہٕ سَتَتِم 78. [arɨsatatʰ] اَرٕسَتَتھ [arɨsatatjum] or [arɨsatatim] اَرٕسَتَتیُٛم or اَرٕسَتَتِم 79. [kunɨʃiːtʰ] کُنہٕ شيٖتھ [kunɨʃiːtjum] or [kunɨʃiːtim] کُنہٕ شيٖتیُٛم or کُنہٕ شيٖتِم 80. [ʃiːtʰ] شيٖتھ [ʃiːtjum] or [ʃiːtjim] شيٖتیُٛم or شيٖتِم 81. [akɨʃiːtʰ] اَکہٕ شيٖتھ [akɨʃiːtjum] or [akɨʃiːtim] اَکہٕ شيٖتیُٛم or اَکہٕ شيٖتِم 82. [dɔjiʃiːtʰ] دۄیہِ شيٖتھ [dɔjiʃiːtjum] or [dɔjiʃiːtjum] دۄیہِ شيٖتیُٛم or دۄیہِ شيٖتِم 83. [trejiʃiːtʰ] ترٛیٚیہِ شيٖتھ [trejiʃiːtjum] or [trejiʃiːtim] ترٛیٚیہِ شيٖتیُٛم or ترٛیٚیہِ شيٖتِم 84. [t͡sɔjiʃiːtʰ] ژۄیہِ شيٖتھ [t͡sɔjiʃiːtjum] or [t͡sɔjiʃiːtim] ژۄیہِ شيٖتیُٛم or ژۄیہِ شيٖتِم 85. [pə̃ːt͡sɨʃiːtʰ] or [pãːt͡sɨʃiːtʰ] پٲنٛژٕ شيٖتھ or پانٛژٕ شيٖتھ [pə̃ːt͡sɨʃiːtjum] or [pãːt͡sɨʃiːtjum] پٲنٛژٕ شيٖتیُٛم or پانٛژٕ شيٖتیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨʃiːtim] or [pãːt͡sɨʃiːtim] پٲنٛژٕ شيٖتِم or پانٛژٕ شيٖتِم 86. [ʃejiʃiːtʰ] شیٚیہِ شيٖتھ [ʃejiʃiːtjum] or [ʃejiʃiːtim] شیٚیہِ شيٖتیُٛم or شیٚیہِ شيٖتِم 87. [satɨʃiːtʰ] سَتہٕ شيٖتھ [satɨʃiːtjum] or [satɨʃiːtim] سَتہٕ شيٖتیُٛم or سَتہٕ شيٖتِم 88. [arɨʃiːtʰ] اَرٕشيٖتھ [arɨʃiːtjum] or [arɨʃiːtim] اَرٕشيٖتیُٛم or اَرٕشيٖتِم 89. [kunɨnamatʰ] کُنہٕ نَمَتھ [kunɨnamatjum] or [kunɨnamatim] کُنہٕ نَمَتیُٛم or کُنہٕ نَمَتِم 90. [namatʰ] نَمَتھ [namatjum] or [namatim] نَمَتیُٛم or نَمَتِم 91. [akɨnamatʰ] اَکہٕ نَمَتھ [akɨnamatjum] or [akɨnamatim] اَکہٕ نَمَتیُٛم or اَکہٕ نَمَتِم 92. [dunamatʰ] دُنَمَتھ [dunamatjum] or [dunamatim] دُنَمَتیُٛم or دُنَمَتِم 93. [trunamatʰ] or [trɨnamatʰ] ترُٛنَمَتھ or ترٕٛنَمَتھ [trunamatjum] or [trunamatim] ترُٛنَمَتیُٛم or ترُٛنَمَتِم [trɨnamatjum] or [trɨnamatim] ترٕٛنَمَتیُٛم or ترٕٛنَمَتِم 94. [t͡sunamatʰ] ژُنَمَتھ [t͡sunamatjum] or [t͡sunamatim] ژُنَمَتیُٛم or ژُنَمَتِم 95. [pə̃ːt͡sɨnamatʰ] or [pãːt͡sɨnamatʰ] پٲنٛژٕ نَمَتھ or پانٛژٕ نَمَتھ [pə̃ːt͡sɨnamatjum] or [pãːt͡sɨnamatjum] پٲنٛژٕ نَمَتیُٛم or پانٛژٕ نَمَتیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨnamatim] or [pãːt͡sɨnamatim] پٲنٛژٕ نَمَتِم or پانٛژٕ نَمَتِم 96. [ʃunamatʰ] شُنَمَتھ [ʃunamatjum] or [ʃunamatim] شُنَمَتیُٛم or شُنَمَتِم 97. [satɨnamatʰ] سَتہٕ نَمَتھ [satɨnamatjum] or [satɨnamatim] سَتہٕ نَمَتیُٛم or سَتہٕ نَمَتِم 98. [arɨnamatʰ] اَرٕنَمَتھ [arɨnamatjum] or [arɨnamatjim] اَرٕنَمَتیُٛم or اَرٕنَمَتِم 99. [namɨnamatʰ] نَمہٕ نَمَتھ [namɨnamatjum] or [namɨnamatim] نَمہٕ نَمَتیُٛم or نَمہٕ نَمَتِم 100. [hatʰ] ہَتھ [hatyum] or [hatim] ہَتیُٛم or ہَتِم 101. [akʰ hatʰ tɨ akʰ] اَکھ ہَتھ تہٕ اَکھ [akʰ hatʰ tɨ ǝkjum] or [akʰ hatʰ tɨ ǝkim] اَکھ ہَتھ تہٕ أکیُٛم or اَکھ ہَتھ تہٕ أکِم 102. [akʰ hatʰ tɨ zɨ] اَکھ ہَتھ تہٕ زٕ [akʰ hatʰ tɨ dojum] or [akʰ hatʰ tɨ dojim] اَکھ ہَتھ تہٕ دۆیُم or اَکھ ہَتھ تہٕ دۆیِم 200. [zɨ hatʰ] زٕ ہَتھ [du hatyum] or [duhatim] دُہَتیُٛم or دُہَتِم 300. [tre hatʰ] ترٛےٚ ہَتھ [trɨ hatyum] or [trɨ hatim] ترٕٛہَتیُٛم or ترٕٛہَتِم 400. [t͡soːr hatʰ] ژور ہَتھ [t͡su hatyum] or [t͡su hatim] ژُہَتیُٛم or ژُہَتِم 500. [pə̃ːt͡sʰ hatʰ] or [pãːt͡sʰ hatʰ] پٲنٛژھ ہَتھ or پانٛژھ ہَتھ [pə̃ːt͡sɨ hatyum] or [pãːt͡sɨ hatyum] پٲنٛژٕ ہَتیُٛم or پانٛژٕ ہَتیُٛم [pə̃ːt͡sɨ hatim] or [pãːt͡sɨ hatim] پٲنٛژٕ ہَتِم or پانٛژٕ ہَتِم 600. [ʃe hatʰ] شےٚ ہَتھ [ʃe hatyum] or [ʃe hatim] شےٚ ہَتیُٛم or شےٚ ہَتِم 700. [satʰ hatʰ] سَتھ ہَتھ [ʃatɨ hatyum] or [ʃatɨ hatim] سَتہٕ ہَتیُٛم or سَتہٕ ہَتِم 800. [əːʈʰ ʃatʰ] ٲٹھ شَتھ [əːʈʰ ʃatjum] or [əːʈʰ ʃatim] ٲٹھ شَتیُٛم or ٲٹھ شَتِم 900. [naʋ ʃatʰ] نَو شَتھ [naʋ ʃatjum] or [naʋ ʃatim] نَو شَتیُٛم or نَو شَتِم 1000. [saːs] ساس [səːsjum] or [səːsim] سٲسیُٛم or سٲسِم 1001. [akʰ saːs akʰ] اَکھ ساس اَکھ [akʰ saːs ǝkjum] or [akʰ saːs ǝkim] اَکھ ساس أکیُٛم or اَکھ ساس أکِم 1002. [akʰ saːs zɨ] اَکھ ساس زٕ [akʰ saːs dojum] or [akʰ saːs dojim] اَکھ ساس دۆیُم or اَکھ ساس دۆیِم 1100. [akʰ saːs hatʰ] اَکھ ساس ہَتھ or [kah ʃatʰ] or [kaːh ʃatʰ] کَہہ شَتھ or کاہ شَتھ [akʰ saːs hatjum] or [akʰ saːs hatim] اَکھ ساس ہَتیُٛم or اَکھ ساس ہَتِم or [kah ʃatjum] or [kaːh ʃatjum] کَہہ شَتیُٛم or کاہ شَتیُٛم [kah ʃatim] or [kaːh ʃatim] کَہہ شَتِم or کاہ شَتِم 1500. [akʰ saːs pãːt͡sʰ hatʰ] اَکھ ساس پانٛژھ ہَتھ or [pandaːh ʃatʰ] پَنٛداہ شَتھ [akʰ saːs pãːt͡sɨ hatjum] or [akʰ saːs pãːt͡sɨ hatim] اَکھ ساس پانٛژٕ ہَتیُٛم or اَکھ ساس پانٛژٕ ہَتِم or [pandaːh ʃatjum] or [pandaːh ʃatim] پَنٛداہ شَتیُٛم or پَنٛداہ شَتِم 10,000. [dəh saːs] or [daːh saːs] دٔہ ساس or داہ ساس [dəh səːsjum] or [daːh səːsjum] دٔہ سٲسیُٛم or داہ سٲسیُٛم [dəh səːsim] or [daːh səːsim] دٔہ سٲسِم or داہ سٲسِم Hundred thousand [lat͡ʃʰ] لَچھ [lat͡ʃʰjum] or [lat͡ʃʰim] لَچھیُٛم or لَچھِم Million [dəh lat͡ʃʰ] or [daːh lat͡ʃʰ] دٔہ لَچھ or داہ لَچھ [dəh lat͡ʃʰjum] or [daːh lat͡ʃʰjum] دٔہ لَچھیُٛم or داہ لَچھیُٛم [dəh lat͡ʃʰim] or [daːh lat͡ʃʰim] دٔہ لَچھِم or داہ لَچھِم Ten million [kɔroːr] or [karoːr] کۄرور or کَرور [kɔroːrjum] or [karoːrjum] کۄروریُٛم or کَروریُٛم [kɔroːrim] or [karoːrim] کۄرورِم or کَرورِم Billion [arab] اَرَب [arabjum] or [arabim] اَرَبیُٛم or اَرَبِم Hundred billion [kʰarab] کھَرَب [kʰarabjum] or [kʰarabim] کھَرَبیُٛم or کھَرَبِم

Remove ads

Vocabulary

Summarize

Perspective

Kashmiri is an Indo-Aryan language and was heavily influenced by Sanskrit, especially early on.[106][107][108] After the arrival of Islamic rule in India, Kashmiri acquired many Persian loanwords.[108] In modern times, Kashmiri vocabulary has imported words from English, Hindustani and Punjabi.[109]

Preservation of old Indo-Aryan vocabulary

Kashmiri retains several features of Old Indo-Aryan that have been lost in other modern Indo-Aryan languages such as Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi and Sindhi.[42] Some vocabulary features that Kashmiri preserves clearly date from the Vedic Sanskrit era and had already been lost even in Classical Sanskrit. This includes the word-form yodvai (meaning if), which is mainly found in Vedic Sanskrit texts. Classical Sanskrit and modern Indo-Aryan use the word yadi instead.[42]

First person pronoun

Both the Indo-Aryan and Iranian branches of the Indo-Iranian family have demonstrated a strong tendency to eliminate the distinctive first person pronoun ("I") used in the nominative (subject) case. The Indo-European root for this is reconstructed as *eǵHom, which is preserved in Sanskrit as aham and in Avestan Persian as azam. This contrasts with the m- form ("me", "my") that is used for the accusative, genitive, dative, ablative cases. Sanskrit and Avestan both used forms such as ma(-m). However, in languages such as Modern Persian, Baluchi, Hindi and Punjabi, the distinct nominative form has been entirely lost and replaced with m- in words such as ma-n and mai. However, Kashmiri belongs to a relatively small set that preserves the distinction. 'I' is ba/bi/bo in various Kashmiri dialects, distinct from the other me terms. 'Mine' is myon in Kashmiri. Other Indo-Aryan languages that preserve this feature include Dogri (aun vs me-), Gujarati (hu-n vs ma-ri), Konkani (hā̃v vs mhazo), and Braj (hau-M vs mai-M). The Iranian Pashto preserves it too (za vs. maa), as well as Nuristani languages, such as Askunu (âi vs iũ).[110]

Variations

There are very minor differences between the Kashmiri spoken by Hindus and Muslims.[111] For 'fire', a traditional Hindu uses the word اۆگُن [oɡun] while a Muslim more often uses the Arabic word نار [naːr].[112]

Remove ads

Sample text

Summarize

Perspective

Perso-Arabic script

Art. 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

سٲری اِنسان چھِ آزاد زامٕتؠ۔ وؠقار تہٕ حۆقوٗق چھِ ہِوی۔ تِمَن چھُ سوچ سَمَج عَطا کَرنہٕ آمُت تہٕ تِمَن پَزِ بٲے بَرادٔری ہٕنٛدِس جَذباتَس تَحَت اَکھ أکِس اَکار بَکار یُن ۔[113]

[səːriː insaːn t͡ʃʰi aːzaːd zaːmɨtʲ . ʋʲaqaːr tɨ hoquːq t͡ʃʰi hiʋiː . timan t͡ʃʰu soːt͡ʃ samad͡ʒ ataː karnɨ aːmut tɨ timan pazi bəːj baraːdəriː hɨndis d͡ʒazbaːtas tahat akʰ əkis akaːr bakaːr jun]

"All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

Sharada script

Verses by Lalleshwari:[114]

𑆏𑆩𑆶𑆅 𑆃𑆑𑆶𑆪 𑆃𑆗𑆶𑆫 𑆥𑆾𑆫𑆶𑆩 𑆱𑆶𑆅 𑆩𑆳𑆬𑆴 𑆫𑆾𑆛𑆶𑆩 𑆮𑆶𑆤𑇀𑆢𑆱 𑆩𑆁𑆘 𑆱𑆶𑆅 𑆩𑆳𑆬𑆴 𑆑𑆤𑆴 𑆥𑇀𑆪𑆜 𑆓𑆾𑆫𑆶𑆩 𑆠 𑆖𑆾𑆫𑆶𑆩 𑆃𑆱𑆱 𑆱𑆳𑆱 𑆠 𑆱𑆥𑆤𑇀𑆪𑆱 𑆱𑆾𑆤𑇆

[oːmuj akuj at͡ʃʰur porum, suj maːli roʈum ʋɔndas manz, suj maːli kani pʲaʈʰ gorum tɨ t͡sorum, əːsɨs saːs tɨ sapnis sɔn.]

"I kept reciting the unique divine word "Om" and kept it safe in my heart through my resolute dedication and love. I was simply ash and by its divine grace got metamorphosed into gold."

𑆃𑆑𑆶𑆪 𑆏𑆀𑆑𑆳𑆫 𑆪𑆶𑆱 𑆤𑆳𑆨𑆴 𑆣𑆫𑆼 𑆑𑆶𑆩𑇀𑆮𑆪 𑆧𑇀𑆫𑆲𑇀𑆩𑆳𑆟𑇀𑆝𑆱 𑆪𑆶𑆱 𑆓𑆫𑆴 𑆃𑆒 𑆩𑆶𑆪 𑆩𑆁𑆠𑇀𑆫 𑆪𑆶𑆱 𑆖𑇀𑆪𑆠𑆱 𑆑𑆫𑆼 𑆠𑆱 𑆱𑆳𑆱 𑆩𑆁𑆠𑇀𑆫 𑆑𑇀𑆪𑆳 𑆑𑆫𑆼𑇆

[akuj omkaːr jus naːbi dareː, kumbeː brahmaːnɖas sum gareː, akʰ suj mantʰɨr t͡sʲatas kareː, tas saːs mantʰɨr kjaː kareː.]

One who recites the divine word "Omkār" by devotion is capable to build a bridge between his own and the cosmic consciousness. By staying committed to this sacred word, one doesn't require any other mantra out of thousands others.

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- At the beginning of a word it can either come with diacritic, or it can be stand-alone and silent, succeeded by a vowel letter. Diacritics اَ اِ، اُ can be omitted in writing. Other diacritics (i.e. آ، أ، ٲ، إ، اٟ) are never omitted. For example, اَخبار "akhbār" is often written as اخبار, whereas أچھ " ȧchh" is never written as اچھ.

- The letter wāw can either represent consonant ([ʋ]) or vowel ([oː]). It can also act as a carrier of vowel diacritics, representing several other vowels وٗ, ۆ, ۄ (uː], [o], [ɔ]). At the beginning of a word, when representing a consonant, the letter wāw will appear as a standalone character, followed by the appropriate vowel. If representing a vowel at the beginning of a word, the letter wāw needs to be preceded by an ạlif, او, اوٗ, اۆ, اۄ.

- This letter differs from do-chashmi hē (ھ) and they are not interchangeable. Similar to Urdu,do-chashmi hē (ھ) is exclusively used as a second part of digraphs for representing aspirated consonants.

- In initial and medial position, the letter hē always represents the consonant [h]. In final position, The letter hē can either represent consonant ([h]) or vowel ([a]). In final position, only in its attached form, and not in isolated form, it can also act as a carrier of vowel diacritics, representing several other vowels ـٔہ, ـہٕ ([ə], [ɨ]). For example, whereas a final "-rạ" is written as ـرٔ, a final "-gạ" is written as ـگٔہ.

- The letter yē can either represent consonant ("y" [j]) or vowel ("ē" [eː] or "ī" [iː]). The letter yē can represent [j] in initial or medial position, or it can represent "ē" [eː] or "ī" [iː] in medial positions, or "ī" [iː] in final position. In combination with specific diacritics, the letter yē in its medial position, can represent "ī" [iː], "e" [e], "ĕ" [ʲa], or ' [◌ʲ] as well. To represent the consonant "y" [j] or the vowel "ē" [eː] in final position, the letter boḍ yē (ے) is used. The letter boḍ yē (ے), in combination with specific diacritics, can represent "e" [e] in final position.

- The letter boḍ yē only occurs in final position. The letter boḍ yē represents the consonant "y" [j] or the vowel "ē" [eː]. With specific diacritics, vowel "e" [e] is also shown with the letter boḍ yē.

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads