Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Tigrayans

Semitic-speaking ethnic group native to northern Ethiopia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Tigrayan people (Tigrinya: ተጋሩ, romanized: Təgaru) are a Semitic-speaking ethnic group indigenous to the Tigray Region of northern Ethiopia.[9][10][11] They speak Tigrinya, an Afroasiatic language belonging to the North Ethio-Semitic language descended from Geʽez, and written in the Geʽez script serves as the main and one of the five official languages of Ethiopia.[12] Tigrinya is also the main language of the Tigrinya people in central Eritrea, who share ethnic, linguistic, and religious ties with Tigrayans.[13]

This article currently links to a large number of disambiguation pages (or back to itself). (August 2025) |

According to the 2007 national census, Tigrayans numbered approximately 4,483,000 individuals, making up 6.07% of Ethiopia’s total population at the time.[14] The majority of Tigrayans adhere to Oriental Orthodox Christianity, specifically the Tigrayan Orthodox Tewahedo Church, although minority communities also follow Islam or Catholicism.[15] Historically, the Tigrayan people are closely associated with the Aksumite Empire whose political and religious center was in Tigray,[16][17][page needed] and later the Ethiopian Empire.[18] Tigrayans played major roles in the political history of Ethiopia, including during the 17th-century Zemene Mesafint (Era of the Princes), and later in the 20th century through events the Woyane rebellion and the Ethiopian Student Movement, or movements like Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), which became the dominant faction in the coalition that overthrew the Derg in 1991 and ruled Ethiopia through the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) until 2018.[19][20]

Like other northern highland peoples, Tigrayans often identify with the broader Habesha (Abyssinian) identity—a term used historically to describe the Semitic-speaking Christian populations of the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands.[21][22]

Areas where Tigrayans have strong ancestral links are: Enderta, Agame, Tembien, Kilite Awlalo, Axum, Raya, Humera, Welkait, and Tsegede. The latter three areas are now under the de facto administration of the Amhara Region, having been forcibly annexed by Amhara during the Tigray War.

Remove ads

Origin

Summarize

Perspective

In his Geographia, the 2nd-century Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy, identifies a people known as the Tigritae or Tigraei (Τιγρῖται), located inland from the Red Sea coast in the area corresponding to the northern Horn of Africa. These names have been interpreted by some modern scholars as a possible early reference to the highlanders of modern-day Tigray and Eritrea.[23][24] Though the identification remains tentative, it is often regarded as the earliest known external allusion to a group or region bearing a name similar to Tigray.[23][24] On top of that, Ptolemy mentions the existence of a city called Coloe (Κολόη), which has been identified with Qohayto in Eritrea, placing his geographical framework close to the Tigray-Tigrinya highlands.[25][26][27][28]

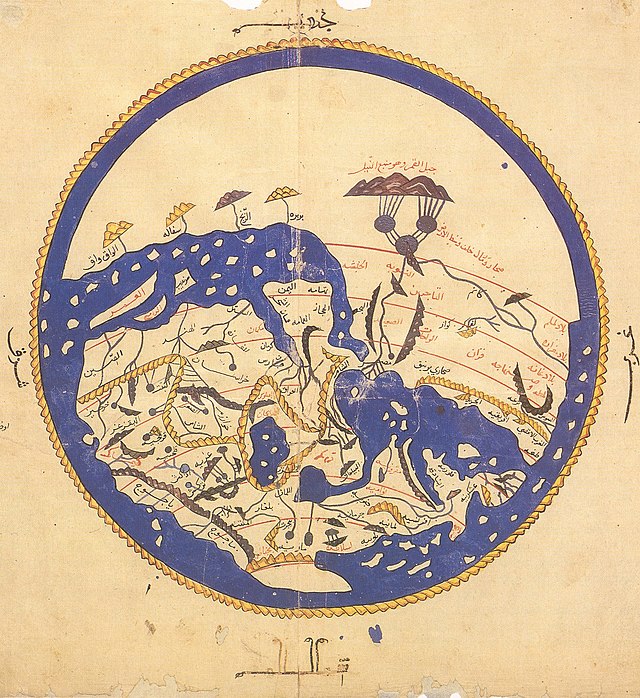

The first clear references of Tigray emerged in 9th- to 12th-century Arabic geographical texts, where Islamic scholars such as Ibn Khurradādhbih, al-Yaʿqūbī, Ibn Ḥawqal, al-Maqdisī, al-Iṣṭakhrī, and al-Idrīsī refer to a region called Tīgrī or Tīgra, identifying it as a distinct Christian province within the broader kingdom of al-Ḥabasha (Abyssinia).[29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36] These sources portray Tigray as a politically and culturally autonomous highland territory, often differentiated from neighboring regions such as Amhār (Amhara) and al-Bajā (Beja), and ruled by its own Christian authorities under the suzerainty of a king (the Negus).[37][38][39]

In his Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik ("The Book of Roads and Kingdoms"), the Persian geographer Ibn Khurradādhbih lists “Tīgrī” (تيغري) as a distinct Christian-inhabited territory under the rule of a king within the lands of al-Ḥabasha (Abyssinia), alongside other regions such as Nubia and al-Bajā (Beja).[29][40] His account marks the first known external textual identification of a distinct ethno-political region in what would later be formalized as Tigray.[29][40] A few decades later, al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897), in his Kitāb al-Buldān ("Book of Countries"), echoed this distinstiguishing Tigri from other regions such as Amhār and Kūstantīn (likely referencing the ancient Christian center of Aksum), this providing one of the earliest external sources to record a regional division resembling Ethiopia's later provinces.[30][41] Al-Iṣṭakhrī, in his own version of al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik, similarly names Tīgrī as one of the Christian territories of the Ethiopian highlands.[42] His contemporary, Ibn Ḥawqal, in his geographical treatise Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ ("The Face of the Earth"), likewise refers to Tīgrī (تيغري) as a distinct region within the broader Christian kingdom of al-Ḥabasha, emphasizing its separation from other regions such as the land of the Beja and Nubians.[31][43]

Shortly thereafter, al-Maqdisī (al-Muqaddasī), writing in his Aḥsan al-Taqāsīm fī Maʿrifat al-Aqālīm ("The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions"), includes Tīgrī in his description of the “land of the blacks” (bilād al-sūdān), specifically noting it as one of several Christian realms inland from the Red Sea. Later, al-Idrīsī, writing in Norman Sicily in 1154 CE, describes “Tīgra” as a province of the kingdom of al-Ḥabasha in his major work Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq. These texts collectively suggest that the toponym "Tigray" (or its variants Tīgrī, Tīgra) had entered the lexicon of Islamicate cartography and ethnography by the early medieval period.[44][45][46][47]

While early Islamic geographers offered some of the first external references to Tigray, it should also be acknowledged that the Christian world, particularly through late antique and medieval sources, retained knowledge of the region primarily through ecclesiastical and geographic lenses. A notable example of that appears in a marginal 10th-century gloss to the works of Cosmas Indicopleustes, a 6th-century Alexandrian merchant and Christian monk who had traveled to the Red Sea. According to this source, the inhabitants of the northern Ethiopian highlands are referred to as the Tigrētai (Greek: Τιγρήται) and the Agazē (Greek: ἀγαζη), the latter term referring to the "Agʿazi" (Ge'ez: አግዓዚ) people, who were associated with the Aksumite ruling elite and Semitic-speaking highlanders.[48]

By the 14th century, the term Tigray appears in Geʽez royal chronicles and administrative records during the reign of Emperor Amda Seyon (1314–1344), referring to a northern province of the Ethiopian Empire governed by regional nobles and military leaders.[49][50] In addition to that, ecclesiastical sources such as the Gädlä Ewostatewos (Hagiography of Ewostatewos) documents the saint’s journeys and religious activities in Tigray, highlighting the region's prominence as a monastic and theological center.[51] Additionally, 15th-century royal land grant charters issued under emperors like Zara Yaqob mention specific districts in Tigray by name—including Tembien, Adwa, and Shire—demonstrating a sustained administrative and fiscal delineation of the region.[52] Administrative land grant documents (Gwǝlt), preserved in church archives, also mention estates located in “the land of Tǝgray,” indicating that the term was used in formal legal and fiscal contexts.[53] Baeda Maryam I's royal chronicle (r. 1468–1478) also describes military campaigns and religious patronage in Tigray, especially the emperor’s support for monastic networks affiliated with Ewostatean traditions.[54] These varied Ethiopian sources confirm that Tigray was not only a geographically defined province but also a central node in the religious, political, and symbolic landscape of the medieval Ethiopian state. Local chronicles from Enderta and Agame also reference Tigray as a broader regional identity, distinct yet integrated within the imperial order.[55]

The earliest known European references to the region of Tigray appear in the 16th century, during the period of Portuguese exploration and diplomatic engagement with the Christian Ethiopian Empire. One of the most important early witnesses was Francisco Álvares, a Portuguese priest and royal envoy who accompanied the 1520–1527 mission to the court of Emperor Lebna Dengel. In his account, Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João das Indias ("A True Relation of the Lands of Prester John of the Indies"), Álvares explicitly names “Tigré” as a major province of the empire. He describes it as a land of stone churches, learned clergy, and ancient Christian traditions, particularly focusing on Aksum, which he identified as the site of royal coronations and religious reverence. Álvares also records the presence of the local nobility and refers to Tigré's role in resisting the Muslim incursions led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi during the early stages of the Ethiopian–Adal war.[56][57]

Following Álvares, the Jesuit missionary Jerónimo Lobo, who traveled through Ethiopia in the early 17th century, also emphasized the importance of Tigré as a Christian stronghold. In his travel narrative Itinerário e outras obras, he recounted the region's churches, monastic communities, and its connections to early Christian relics and traditions, including associations with the Ark of the Covenant in Aksum. He identified Tigré as distinct from other provinces such as Amhara or Shewa, and praised the piety and hospitality of its people. His writings were later translated and popularized in English by Samuel Johnson, further spreading knowledge of Tigré among European readers.[58][59]

In the later 17th century, the most comprehensive European treatment of Ethiopian geography and culture was produced by Hiob Ludolf, a German orientalist and linguist whose Historia Aethiopica (1681) became the standard European reference on Ethiopia for decades. Ludolf based his work on Ethiopian sources, interviews with Ethiopian monks and emissaries in Rome, and correspondence with Jesuit missionaries in the Horn of Africa. He refers to Tigray as “Regio Tigrensis” or “Tigraia”, describing it as one of the core regions of the Empire. Ludolf notes its proximity to the Red Sea, its connection to the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, and its linguistic particularities — identifying Tigrinya as a variant of Geʿez still spoken by the people of the region. He includes maps and ethnographic details that distinguish Tigray from neighboring regions such as Amhara and Begemder.[60][61]

These early European sources consistently depicted Tigray not only as a geographically distinct province but also as a religious and historical heartland of the Ethiopian state. They frequently associated it with the memory of Aksumite kingship, monastic scholarship, and the ecclesiastical authority of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[62][63][64] Over time, references to "Tigré" and "Tigrai" became standard in European maps and writings on the region, including those by cartographers such as Ortelius, Blaeu, and d’Anville, who often marked “Tigre Regio” or “Regnum Tigré” on maps of East Africa produced between the 16th and 18th centuries.[65][66][67]

The Scottish explorer James Bruce, writing in the late 18th century, described Abyssinia as geographically divided into two principal provinces: “Tigré, which extends from the Red Sea to the river Tacazzé; and Amhara, from that river westward to the Galla, which inclose Abyssinia proper on all sides except the north-west.” Moreover, he emphasized the commercial importance of Tigray due to its proximity to the Red Sea trade routes:

"Tigré is a large and important province, of great wealth and power. All the merchandise destined to cross the Red Sea to Arabia must pass through this province, so that the governor has the choice of all commodities wherewith to make his market."[68]

By the early 19th century, English diplomat and Egyptologist Henry Salt also emphasized the strategic and military strength of Tigray. In his 1816 account A Voyage to Abyssinia, Salt identified three great divisions of the Ethiopian highlands: Tigré, Amhara, and Shewa.[69][70] He considered Tigré to be the most powerful of the three, citing “the natural strength of the country, the warlike disposition of its inhabitants, and its vicinity to the sea coast,” which enabled it to secure a monopoly on imported muskets.[71]

Salt further subdivided the kingdom of Tigré into smaller provinces, referring to the heartland as Tigré proper. This included districts such as Enderta, Agame, Wojjerat, Tembien, Shiré and Baharanegash.[72] Within Baharanegash, the northernmost district of Hamasien marked the edge of Tigré, beyond which Salt noted the presence of the Beja (or Boja) people living further north.[71][73][74]

Ethnogenesis

Tigrinya is a North Ethio-Semitic language, closely related to Geʽez and spoken primarily by the Tigrayans and the Tigrinya people of central Eritrea.[75][76] The ethnogenesis of the Tigrayan people is rooted in the interaction between Semitic-speaking Aksumites, who spoke early forms of Geʽez, and the Cushitic-speaking populations inhabiting the northern Horn of Africa, such as the Agaw.[77][78] During the height of the Kingdom of Aksum (c. 1st–7th century AD), the political, religious, and linguistic center of the empire was located in modern-day Tigray and Eritrea, with cities like Aksum and Adulis serving as hubs of trade, Christianity, and imperial administration.[79][17][page needed]

Building on this historical foundation, scholars have identified the term Agʿazi (Geʽez: አግዓዚ) in early inscriptions and royal texts from the pre-Aksumite and Aksumite periods, as referring to both a Semitic-speaking people and their language, widely seen as ancestral to the Tigrinya-speaking populations of the northern highlands. Modern scholars regard the Agʿazi as the direct ethnolinguistic ancestors of the Tigrayan and Tigrinya populations of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, rather than of the Amhara, whose language and sociopolitical structures evolved farther south under different influences.[80][81] The development of Geʽez into Tigrinya and Tigre is thus seen as a process of regional linguistic continuity, whereas Amharic—while part of the broader Ethio-Semitic family—emerged in a later context, shaped by Cushitic substrata and more distant from the core Agʿazi heritage.[82][83]

As the Aksumite polity declined and political power shifted southward, many northern highland communities continued to speak local derivatives of Geʽez, giving rise to Tigrinya as a distinct vernacular language by the early second millennium.[84][85] The gradual consolidation of Tigrinya-speaking communities, coupled with common religious affiliation to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and localized political traditions (such as the rules of Bahr negash and Tigray Mekonnen in northern Tigray and Eritrea), fostered the emergence of a coherent Tigrayan identity.[86][87] Archaeological, linguistic, and historical evidence suggest that the Tigrayan ethnolinguistic group thus emerged through a long process of ethno-cultural continuity and differentiation within the broader Aksumite and post-Aksumite highland society.[88][89]

Moreover, the British explorer Charles Tilstone Beke, who traveled in Ethiopia in the 1840s, asserted that the Tigréans and Amharas were “two different races, differing in language, character, and physiognomy”, and argued that the Tigréans were the “true representatives of the ancient Abyssinians” due to their continuity with the Aksumite heritage.[90] His conclusions reflected a broader trend among 19th-century European travelers—such as James Bruce, Henry Salt, and later Theophilus Waldmeier—who associated the Tigrayan people with the historical legacy of the Aksumite Empire, and by extension, the classical Christian civilization of Ethiopia.[91][92][93] This association was often based on the concentration of early Christian monuments in Tigray (particularly in Aksum, Yeha, and Adwa), the continued use of Tigrinya, a language derived from Geʽez, and the presence of monastic traditions viewed as direct descendants of early Ethiopian Orthodoxy.

Later scholars, such as Edward Ullendorff, would argue that the linguistic and religious conservatism of the northern highlands (especially the retention of Geʽez in church liturgy and the preservation of Aksumite ruins) contributed to a historical self-perception among Tigrayans as guardians of ancient Ethiopian identity, in contrast to the Amhara, who came to political prominence in later medieval and early modern periods.[94]

Etymology

The toponym Tigray is probably originally ethnic, the Tigrētai then meant "the tribes near Adulis." These are believed to be the ancient people from whom the present-day Tigrayans, the Eritrean tribes Tigre and Tigrinya are descended from.[48]

Although the linguistic roots of the name Tigray are not definitively established, several theories exist. Some scholars link it to the Geʽez root "ተገረ" (Tagära), meaning “to ascend” or “upper place,” possibly referring to the elevated terrain of the Tigrayan plateau.[95] A common theory holds that Tigray is a later evolution of the root “T’GR”, which may have originally referred to a specific sub-region or population within the Aksumite kingdom.[96] In this reading, the word may have designated the central-northern highland area from which the language now known as Tigrinya later emerged.[97]

Another strand of scholarship focuses on the ethnonym Təgaru (ተጋሩ) — the endonym used in Tigrinya to refer to the Tigrayan people — and its relation to the language name Tigrinya (ትግርኛ, Tǝgrǝñña). Some linguists argue that the root TGR is not only geographic (as in Tigray) but also ethno-linguistic, originally designating speakers of a Geʽez-derived northern Semitic language who maintained cultural and political continuity from the Aksumite period.[98] The suffix (Ge'ez: ኛ, romanized: inya) as in Tigrinya: ትግርኛ, romanized: Təgrəñña is a typical Amharic-derived marker for languages or affiliations (comparable to Amharic: አማርኛ, romanized: Amarəñña from Amhara), making Tigrinya literally mean "of the Tigray" or "Təgaru-related".[99]

While some late sources have occasionally associated Təgaru with wider Semitic groups, most academic interpretations consistently link it to the inhabitants of the central-northern highlands, particularly those whose liturgical and linguistic practices descend from Geʽez.[100][81] This framing further reinforces the distinction between Tigrinya as an indigenous highland language and the later emergence of Amharic to the south.[99]

Some marginal interpretations, often found in 20th-century colonial-era dictionaries or speculative linguistic notes, attempt to impose a rigid social hierarchy between the Agʿazi (or "Gäzé") and the Tigretês, framing the former as “nobles” and the latter as socially subordinate or ethnically mixed. However, this interpretation has been challenged by scholars who argue that the derivation of Təgaru from the Geʽez root gäzärä (ገዘረ, “to subdue”) is speculative and lacks support from primary Aksumite inscriptions or early literary sources.[81][98] Rather than being socially subordinate or external to the Aksumite elite, the forefathers of the Tigrinya-speaking communities were integral to the Aksumite Empire, especially in the preservation and transmission of Geʽez, Orthodox Christianity, and classical architecture. Their historical centrality is evidenced by their custodianship of core highland religious and cultural centers such as Aksum, Yeha, and Debre Damo.[17][page needed][101][102] Moreover, linguistic studies affirm that terms like Təgaru and Tigrinya derive from indigenous Ethio-Semitic roots linked to the highland region—not from imposed designations of subjugation.[99][82] As such, framing the Tigrétês as a socially inferior group distinct from the Agʿazi overlooks the ethno-linguistic continuity and cultural authority of the northern highland populations, who were among the primary successors of the Aksumite Empire.[103][104][105][106]

In modern usage, "Tigray" refers to both the region and the ethnic group primarily residing in Ethiopia’s northern highlands, while "Tigrayan" (Tigrinya: ተጋሩ, romanized: Təgaru) designates the people, language, and shared cultural identity associated with that region.[107][81][108][109] The term remains distinct from but historically related to Tigre, which refers to a different ethnic group speaking the Tigre language in Eritrea.[110][111]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The Tigrayan people's long and rich history is undoubtedly intertwined with the formation of the Ethiopian state, its religious traditions, and the development of its distinct cultural identity. Due to its pivotal role in early Ethiopian history, particularly as the heartland of its ancient Semitic civilizations like D'mt or the Kingdom of Aksum, Tigray is sometimes designated as the "cradle of Ethiopian civilization."[112]

According to Edward Ullendorff, the Tigrinya speakers in Eritrea and Tigray are the authentic carriers of the historical and cultural tradition of ancient Abyssinia.[113] For their part, Donald N. Levine and Haggai Erlich regard the contemporary Tigrayans to be the successors of the Aksumite Empire.[114]

Kingdom of D'mt

The Tigrayans trace their origin to early Semitic-speaking peoples whose presence in the region may date back to at least 2000 BC.[17][page needed] One of the first known civilizations to emerge in the area was the Kingdom of D'mt, which flourished around the 10th century BCE. The capital of this ancient kingdom may have been near modern-day Yeha, where the remains of a large temple complex and fertile surroundings suggest a well-established and advanced society.[115] Indeed, D'mt was known for its advanced agricultural practices, including the use of ploughs and irrigation systems, as well as its production of iron tools and weapons. Archaeological evidence suggests that D'mt was an important center of trade, interacting with surrounding regions, especially Arabia and the broader Red Sea world.[116]

However, the origins of D'mt have been a subject of scholarly debate. Some historians, such as Stuart Munro-Hay, Rodolfo Fattovich, Ayele Bekerie, Cain Felder, and Ephraim Isaac, view the civilization as primarily indigenous, though influenced by Sabaean culture due to the Sabaeans' dominance over the Red Sea trade routes.[17][page needed][117] Others, including Joseph Michels, Henri de Contenson, Tekletsadik Mekuria, and Stanley Burstein, suggest that D'mt emerged from a blend of Sabaean and indigenous peoples, reflecting a synthesis of Arabian and local African cultural influences.[118][119]

Aksumite Empire

By the 1st century CE, D'mt had been supplanted by the rise to prominence of the Aksumite Empire in the region. Centered around Tigray and Eritrea, it quickly established itself as one of the most powerful civilizations of antiquity alongside Rome, Persia, and China by controlling much of the Red Sea coast, parts of the Arabian Peninsula, and modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Moreover, its strategic position also made it a powerful player in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade networks with the exportation of luxury goods such as ivory, gold, frankincense, and myrrh and the importation of silk, wine, and other exotic goods, which allowed it to prosper and expand its influence far beyond the Horn of Africa.[120][121][122][123]

On top of that, the empire was also renowned for its technological and architectural feats, which highlighted both its advanced engineering and cultural significance.

The Aksumites erected monumental stelae and obelisks such as the Ezana Stone or the Obelisk of Axum, which were used either as grave markers for Aksumite royalty or as testaments to both their political and religious power while remaining to this day one of the most iconic symbols of the empire's grandeur.[124] Their advanced water management systems, including dams and irrigation channels, enabled the empire to sustain agricultural productivity and support its growing population, further solidifying its economic base.[125]

Aksumite legacy on Tigrayan cultural identity

The Aksumite legacy is deeply embedded in Tigrayan identity, as the people of Tigray are the direct cultural, territorial, and religious heirs of the Aksumite civilization. The core territory of the Aksumite kingdom lies squarely within modern-day Tigray, and many of the civilization’s major architectural and religious landmarks—including the city of Aksum itself, the obelisks, and ancient church sites—remain integral to Tigrayan cultural and spiritual life.[126][127][128]

As such, the arrival of Christianity and subsequent conversion of King Ezana in the 4th century CE made Aksum one of the earliest empires to adopt Christianity as the state religion, and thus represented a crucial turning point in the religious and cultural development of the Tigrayan people as they not only preserved the newly adopted faith but also helped developing it into the uniquely Ethiopian form of Christianity that would endure throughout the latter's tumultuous history.[125][129][130][131] This shift towards Christianity also led to the establishment of churches, monasteries, and religious institutions throughout Tigray and Eritrea, many of which became centers of learning, intellectual exchange, theological development, thereby nourishing the emergence of the early Ethiopian literature.[125][132]

This identification is further strengthened by linguistic and religious continuity. The Geʽez language, used in Aksumite inscriptions and royal declarations, survives today as the liturgical language of all Orthodox Tewahedo Churches, which remains dominant in Tigray.[133][134] Tigrinya, the modern language of the Tigrayan people, is a direct descendant of this ancient Semitic linguistic tradition, preserving many features of Aksumite syntax and vocabulary.[135][136] Religious institutions in Tigray—particularly the ancient monasteries and churches around Aksum—continue practices, liturgies, and theological interpretations that trace their roots to Aksumite Christianity, further entwining the past with the living identity of the region’s population.[137][138][139]

A great example is the fact that Aksum became the holiest site of Ethiopian Orthodoxy, due to the belief that the Ark of the Covenant resides at the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion after being brought by its first legendary Emperor Menelik I.[140] This tradition, found in the Kebra Negast, firmly wove the Tigrayan highlands into Ethiopian Empire’s political and spiritual fabric, ensuring that the memory of Aksum remained inseparable from the ideals of kingship, unity, and divine favor that would define the Ethiopian Empire.[141][131] As the city became a cornerstone of imperial legitimacy and national identity, successive Ethiopian emperors deliberately sought to anchor their authority in the city's sacred legacy, with coronation ceremonies in Aksum becoming an indispensable rite of passage.[142][143]

Beyond language and religion, historical narratives in Tigray often place the Aksumite period at the foundation of Tigrayan identity. Educational curricula, oral traditions, and cultural commemorations in the region frame Aksum not only as a shared Ethiopian heritage but as a particularly Tigrayan inheritance—distinct from other ethnonational identities in Ethiopia.[144][145][146][131][141] In this regard, the city of Aksum and its surrounding highlands serve as enduring symbols of civilizational prestige and spiritual legitimacy, shaping how Tigrayans view their historical role within the Ethiopian polity and the broader Horn of Africa. [147][148][149]

For Tigrayans, Aksum is not a distant historical abstraction but a living component of their local environment and collective memory.[150][151] Indeed, their connection to biblical history (with the story of the Ark of the Covenant), coupled with the region's thriving monastic and religious culture, bestowed upon the city of Aksum—and by extension, the Tigrayans—a distinct spiritual status. This heritage positions them not only as custodians of Ethiopia's earliest civilization but also as the guardians of the Christian faith in Africa.[152][141][153][154] Modern historical narratives and textbooks in Tigray often emphasize Aksum as the starting point of Tigrayan and Ethiopian civilization, contributing to a regional historiography that centers Tigray in the broader Ethiopian national story. This selective memory also served both to legitimize political claims and to foster cultural cohesion among Tigrayans, particularly in times of external threat or internal fragmentation. [155][156][157]

For all these reasons, proeminent historians such as Edward Ullendorff, Donald N. Levine and Haggai Erlich regard the contemporary Tigrayans (and Tigrinyas in Eritrea) as the successors of the Aksumite Empire and the authentic carriers of the historical and cultural tradition of ancient Abyssinia.[113][114]

Zagwe dynasty (1137-1270)

During the Zagwe dynasty, Tigray played a significant role in both the political and religious development of the Ethiopian highlands. While Zagwe kings themselves came were not from Tigray but from the Lästä region, they nonetheless claimed descent from Aksumite nobility despite their Agäw origins and remained closely connected to the northern highlands, particularly through monastic institutions and ecclesiastical networks centered in Tigray.[158][159] Important religious centers such as Debre Damo, Debre Maryam Qorqor, and Debre Abbay in Tigray remained active throughout the Zagwe period, serving as centers of theological learning, manuscript production, and regional authority.

While the Zagwe court attempted to establish legitimacy through monumental church-building projects in Lästä (such as the famous rock-hewn churches of Lalibela), they also relied on the prestige of Aksumite ancestry, which remained rooted in Tigray's cultural memory. Several traditions, preserved in later Ethiopian chronicles and hagiographies, suggest that the clergy and monastic elite in Tigray acted as both legitimizers and critics of the Zagwe monarchs, often urging a return to the Solomonic line associated with Aksum.[17][page needed][160]

This ethnic and cultural connection to Tigray allowed the Zagwe rulers to establish a powerful religious and political network that thrived in the northern highlands. Tigrayan nobles provided military and administrative support to the Zagwe kings, and their loyalty ensured the persistence of the dynasty, despite challenges from external and internal forces.[161][162] For instance, King Lalibela married a woman from the Tigrayan aristocracy to strengthen the dynasty's rule over the region.[163]

Solomonid Dynasty (1270-1974)

Early Solomonic Period (1270-1632)

Early Modern Period (1632–1855)

Modern Period (1855-1974)

Contemporary Era (1974-present)

The Ethiopian Revolution and the rise of the TPLF (1974-1991)

The EPRDF in power (1991-2018)

The Tigray War and its aftermath (2020-present)

Remove ads

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

The 2007 Ethiopian census recorded 4,483,741 Tigrayans in Ethiopia, making up 6.1% of the national population and constituting the fourth largest ethnic group in the country after the Oromo, Amhara and Somali.[164][165] However, independent estimates placed the population closer to 5.5–6.3 million by 2020, just before the outbreak of the Tigray War.[166][167][168]

As of 2023, ethnic Tigrayans are estimated to range between 4.0 and 4.5 million inside Ethiopia, with a global estimate ranging from 5.7 to 7.3 million when diaspora populations are included, though precise figures are difficult to ascertain due to recent war-related demographic shocks, forced displacement, and restricted access to accurate census data.[169][170][171] The predominantly Tigrayan-populated urban centers are found in towns including Mekelle, Adwa, Axum, Adigrat, and Shire. Huge populations of Tigrayans are also found in other large Ethiopian cities such as the capital Addis Ababa and Gondar.

Accurate population data is difficult to obtain due to the effects of the Tigray War (2020–2022), which caused widespread destruction of civil registries, mass displacement, and restrictions on humanitarian access. Independent estimates suggest that between 385,000 and 600,000 Tigrayans may have died from direct violence, famine, and lack of medical care during the conflict.[172][173][174] Over 60,000 people fled to Sudan, and hundreds of thousands were internally displaced.[175] Human rights organizations have described these events as ethnic cleansing and genocide, particularly in Western Tigray, where Amhara regional forces forcibly expelled Tigrayan civilians and erased local administrations.[176][177]

In the 19th century, foreign observers such as James Bruce and Henry Salt described Tigray as one of the most populous and politically dominant regions in the Ethiopian Highlands.[178][179] At the time, Tigray was a center of imperial politics, literacy, and trade, often rivaling Shewa in military and cultural influence. However, its share of the national population gradually declined over the subsequent two centuries due to a combination of environmental, political, and economic factors.

The decline of Tigrayan population can be traced back to the Kifu Qen (Amharic: ክፉ ቀን, lit. “evil days”), the great famine of 1888–1892. Triggered by drought, locust invasions, and a devastating rinderpest outbreak, the famine severely affected the Ethiopian highlands, particularly in Tigray, wiping out over 90% of Ethiopia's cattle, the collapse of entire communities, and causing the deaths and displacements of hundreds of thousands of people.[180][181][182][183] The effects of this “evil time”—including mass mortality, displacement, and social disintegration—left long-term demographic scars and are often cited as the beginning of Tigray's descent from a dominant regional power to a peripheralized province.[184][185][186] Another major demographic crisis occurred during the 1958 famine in Tigray, which reportedly killed over 100,000 people.[187][188][189][190] This was followed by a more devastating episode during the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, which disproportionately affected Tigray, Wollo, and Eritrea.[191][192] The Derg military regime under Mengistu Haile Mariam used the famine as a counter-insurgency strategy against the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), deliberately withholding food aid from rebel-held and civilian areas in what scholars and aid workers described as a politicized famine.[193][194][195] According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the famine killed more than 300,000 people, and some estimates place the toll as high as 1.2 million.[196][197]

In the 1990s, the creation of Ethiopia's ethnic federal system led to the incorporation of Welkait, Tsegede, and Tselemti—formerly part of the historical Begemder province—into the newly formed Tigray Region.[198][199] This move was justified by the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) based on local identity and self-determination, but was contested by Amhara political forces. During the Tigray War, these districts were retaken by Amhara forces, who conducted mass expulsions of Tigrayan residents and took control of local administrations.[200][176]

As a result of decades of instability, war, and repression, many Tigrayans have emigrated. The Tigrayan diaspora in the United States alone is estimated to include over 20,000 first-generation migrants, with tens of thousands more in second-generation or undocumented populations.[201][202] Large diaspora populations are also found in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Nordic countries, Sudan, and the Gulf States.[203][204]

Subregions

Although the Tigrayans constitute a single ethnolinguistic people, internally they have long exhibited regional and historical sub-identities with their own socio-cultural traditions that correspond to specific highland districts, dialect zones, and former local principalities.[205][206]

Historically, Tigray was divided into semi-autonomous districts ruled by hereditary elites bearing titles such as Shum Agame, Shum Tembien, and Shum Enderta.[207] These principalities—like Enderta, Tembien, and Agame—served as religious and political centers tied to the broader imperial structure. Agame, for example, bordered modern Eritrea and often supplied high-ranking clergy and officials.[208] While autonomous in certain eras, they were interconnected through marriage alliances, military coalitions, and a common allegiance to the Christian highland polity centered in Aksum and later in Adwa and Mekelle.[209][210]

The central and eastern highlands—including Enderta, Tembien, and Agame—formed the historic core of Tigray and were home to major monasteries, Christian institutions, and leaders like Ras Mikael Sehul, Ras Wolde Selassie, Shum Agame Sabagadis Woldu and Ras Alula Engida.[211] The southern districts, notably Raya and Ofla, lie at a cultural crossroads with the Amhara and Afar peoples but remain firmly rooted in Tigrayan identity through language, kinship, and religious affiliation.[212] To the west, areas such as Welkait, Humera, and Tsegede were long inhabited by Tigrinya-speaking Tigrayans and historically administered as part of Tigray, though they became zones of violent displacement and identity-based repression during the Tigray War (2020–2022).[213]

Remove ads

Language

Summarize

Perspective

Tigrinya (ትግርኛ) is a North Ethio-Semitic language spoken by an estimated 7 to 9 million people across the Horn of Africa, making it one of the most widely spoken Ethio-Semitic languages after Amharic.[214][215] Tigrinya is closely related to Amharic and Tigre, another Ethio-Semitic language spoken by the Tigre as well as many Beja of Eritrea and Sudan. Tigrinya and Tigre, though more closely related to each other linguistically than either is to Amharic, are however not mutually intelligible. Tigrinya has traditionally been written using the same Ge'ez alphabet (fidel) as Amharic and Tigre.

In Ethiopia, Tigrinya is the principal language of the Tigray Region, spoken by approximately 6 to 7 million people[216][217], compared to Eritrea's 2.5 to 3 million Tigrinya-speakers.[218][219] Thus, according to Ethnologue, the Tigrayans comprise over 74% of all Tigrinya native speakers clearly outweighing the number of Eritrean Tigrinya-speakers (26%).[216]

Though mutually intelligible, both varieties have developed under different political and educational systems, leading to subtle differences in orthography, terminology, and media standardization.[220]

Tigrinya traces its roots in the ancient Geʽez-speaking Kingdom of Aksum. As Geʽez ceased to be spoken as a vernacular by around the 10th century CE, descendant languages began to emerge in the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands. It is believed to have developed as a distinct spoken language during the early medieval period, evolving primarily in the highlands of Tigray and Eritrea. The earliest known written attestation of Tigrinya is found in a 13th-century land grant inscription discovered in the Monastery of Däbrä Maryam Qorqor in eastern Tigray, contains grammatical features and vocabulary that diverge from classical Geʽez and are widely recognized as early Tigrinya.[221][222][223]

The linguistic continuity between Geʽez and Tigrinya was reinforced by the use of Geʽez in church liturgy and scriptural translation, while Tigrinya remained a spoken vernacular used in day-to-day life. Over centuries, the consolidation of Tigrinya-speaking communities in provinces such as Enderta, Agame, and Tembien contributed to the shaping of a shared ethnolinguistic identity among Tigrayans, distinct from their northern Tigre-speaking and southern Amharic-speaking neighbors.[77][86]

Dialects

Several Tigrinya dialects, which differ phonetically, lexically, and grammatically from place to place, are more broadly classified as Eritrean Tigrinya or Tigray (Ethiopian) dialects.[224] No dialect appears to be accepted as a standard.

Within the Tigray Region, Tigrinya exhibits notable phonological, morphological, syntactic, and lexical variation. Regions such as Alamata and Wajirat in southern Tigray display features influenced by Amharic, whereas northern and central zones like Enderta, Agame, Adwa, Axum, Shire, and Raya Azebo maintain regional continuity, resulting in differing yet mutually intelligible dialects.[225][226] A Tigray proverb metaphorically captures this internal variation: “Tigrinya was born in Adwa, became sick in Agame, severely sick in Enderta and finally was buried in Raya,” often interpreted as humorously illustrating the tongue’s shifting dialectal “health” from north to south.[227]

Machine-learning research categorizes Tigray-based varieties alongside wider groupings, merging multiple zones into synthesized dialect labels (e.g., “Z,” “L,” “D”), derived from prior works distinguishing northern, central, and southern dialects within Tigray.[228][229] Field descriptions emphasize that phonological shifts (e.g., vowel realization, consonant gemination) and lexical differences (borrowings from Amharic or Saho) are the main markers of variation, but everyday communication across Tigray remains fluid, and standard written Tigrinya used in education, media, and administration largely neutralizes regional disparities.[230][231]

While Tigrinya in Tigray and in Eritrea shows minor differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and idiomatic expressions, these are comparable to regional differences within a single national language elsewhere. Linguists consistently classify both as the same language, belonging to the Ethio-Semitic branch, with high mutual intelligibility across the Ethiopia–Eritrea border.[232][233][234]

Remove ads

Religion

Summarize

Perspective

Aksumite polytheism

Before the adoption of Christianity in the 4th century CE, the ancestors of the Tigrayan people practiced a polytheistic religion that incorporated both indigenous African beliefs and external influences from South Arabia. Several deities were worshipped, including Almaqah, the moon god also revered by the Sabaeans, as well as other Semitic gods such as the sun god Utu, ʾĪlā and Wadd.[235][236] These practices were especially prominent during the pre-Aksumite and early Aksumite periods, which had strong Red Sea trade links with ancient Yemen.

Archaeological remains such as the Temple of Yeha in Tigray, dated to the 7th century BCE, show clear South Arabian architectural influence and are believed to have served as temples dedicated to Almaqah.[237] Other sites across the region feature shaft tombs, stelae, and altars used in pre-Christian ritual activity. The use of the Musnad script and references to Arabian deities in local inscriptions point to a period of religious syncretism before the Christianization of the region under Emperor Ezana.[238][239]

Christianity

Oriental Orthodoxy

Christianity has been the predominant religion of Tigrayans since antiquity. The vast majority of Tigrayans are adherents of Tewahedo Oriental Orthodoxy, specifically the Tigrayan Orthodox Tewahedo Church which has historically been the dominant religious institution in the region.[86][240] In fact, Tigray is often regarded as the spiritual heartland of Ethiopian Orthodoxy, due to its association with the early Christian Kingdom of Aksum. According to tradition and early inscriptions, Christianity was introduced to Aksum in the 4th century CE by St. Frumentius (Ge'ez: አባ ሰላማ ከሳተ ብርሃን, romanized: ʾAbbā Sälāmā Käsātä Bərhān),[a] who was consecrated as the first Bishop of Ethiopia by St. Athanasius, the Patriarch of Alexandria.[17][page needed][77]

Another pivotal moment for Tigrayan Christianity is the arrival of the Nine Saints (Ge'ez: ቱዐታት ቅዱሳን, romanized: Tuʾātāt Qeddusān)[b] during the late 5th to early 6th century CE. These ascetic monks, traditionally said to have come from the Byzantine Syria, are credited with reviving Christian monasticism in the Aksumite realm following the conversion of King Ezana. Settling in different parts of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, particularly in Tigray, they established monasteries, schools, and churches, translated biblical and patristic texts into Geʽez, and promoted Miaphysite doctrine and monastic discipline.[241][242]

Among the most prominent foundations associated with the Nine Saints are the monasteries of Debre Damo (founded by Abuna Aregawi), Abuna Yemata Guh, Abba Pantalewon, Mata Mekel, Mesḥa, and May Qoybah which became hubs of theological learning and spiritual authority, and played a key role in shaping Ethiopian monastic architecture, hymnography, and liturgy. The saints are also credited with standardizing the use of the Geʽez language for liturgical purposes and transmitting elements of Syriac and Coptic Christian thought into the Ethiopian context.[243][244] The legacy of the Nine Saints adds to Tigray’s reputation as a cradle of Ethiopian Orthodox monasticism and theological development.[245][246]

Tigray is also home to some of the oldest and most significant churches such as the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, Abreha we Atsbeha, Teka Tesfay, but also numerous rock-hewn churches, many of which are believed to predate the more famous monolithic churches of Lalibela. Numbering over 120, they contain mural iconography that reflects a synthesis of Byzantine, Coptic, and local Ethiopian styles, depicting biblical scenes, saints, and angels with distinct Tigrayan features and attire.[247]

In addition, the region has long been a center of religious art and manuscript production within the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition. The region's churches and monasteries are renowned for their wall paintings, carved icons, illuminated manuscripts, and rock-hewn architecture,[248][249] while contributing significantly to the transmission and preservation of Ge'ez religious texts, producing manuscripts in local scriptoriums that combined calligraphy, theological commentary, hymnography (zema), and illustrated miniatures.[88][250][251][252] Several Tigrayan monasteries served as centers of Orthodox clerical education and liturgical training and oral transmission of Ge'ez chants, prayers, and exegetical tradition.[253]

This long-standing manuscript and monastic tradition in Tigray is closely intertwined with the development of the region's unique liturgy and sacred chant. The origins of this rich liturgical and musical heritage are traditionally attributed to Saint Yared, a Tigrayan-born composer and scholar who is credited with developing the Zema, a system of sacred music composed in Ge'ez, which still serves as foundation of all Tewahedo, Ethiopian Catholic and Eritrean Catholic liturgical practice.

His compositions are preserved in major chant books such as the Deggua, which contains hymns for feast days and daily services, the Zema Zēta, used for antiphonal chants, and the Mewas'et, which includes funeral music. Taught and transmitted through oral tradition in monastic liturgical schools, Yared's system remains integral to the identity of Ge'ez rite worship and is particularly revered in the churches and monasteries of Tigray, where his legacy is most closely tied.[254][255][256]

Throughout medieval and early modern Ethiopian history, Tigrayan clergy and monastic communities were highly influential in shaping theological debates, religious practices, and church-state relations. Monastic movements such as those founded by Ewostatewos and Abba Estifanos of Gwendagwende originated in Tigray and advocated for liturgical purity, Sabbath observance, and a stricter interpretation of Orthodox tradition. The followers of Ewostatewos (Ewostathians) played a major role in defending indigenous religious practices against foreign and royal interventions, eventually influencing national doctrine.[86][257]

The ecclesiastical office of the Bahre Negeśt, often based in the coastal and highland regions of Tigray, was historically responsible for administering large Orthodox dioceses and coordinating religious authority between the center and the periphery.[258]

Prominent Ethiopian Orthodox saints and writers, including Abba Yohanni of Däbrä Qwästos, Abba Libanos and Abba Samuel of Waldebba, are also traditionally associated with the region. These figures contributed to the development of mystical theology, fasting practices, and monastic discipline within the Orthodox tradition.[259][260] Many of their monasteries remain active pilgrimage sites today, particularly during feast days and local fasts.

In modern times, the Orthodox Church continues to play a central role in the religious and cultural identity of Tigrayans, with most rural communities organized around local parishes, feast-day observances, and monastic networks.

Catholicism

Catholicism among the Tigrayan people has historical roots in the Jesuit missions of the 16th and 17th centuries. During this period, Portuguese-supported missionaries such as Francisco Álvares, Pedro Páez and Manuel de Almeida established religious centers in the northern highlands, notably at Fremona, near Adwa, which served as the Jesuit headquarters in Ethiopia. While the mission ultimately failed due to local resistance and the imperial expulsion of the Jesuits in 1632, it introduced Roman Catholic theological concepts and liturgical influences that would later be revived.[261][262]

The modern Catholic presence in Tigray Region is mainly associated with the Ethiopian Catholic Church, a sui iuris church of the Eastern Catholic Churches that follows the Alexandrian Rite, similar in structure to the Orthodox Tewahedo Churches but in full communion with the papacy. Catholicism was reintroduced in the 19th century through the efforts of Lazarists and Capuchin missionaries, supported by the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide). Their activities focused on education, translation, health, and liturgical accommodation to local customs.[263][264] These missions laid the foundations for the establishment of the Eparchy of Adigrat in 1939, which today is the main ecclesiastical seat for Catholics in northern Ethiopia.[265][266]

As of the early 21st century, the Eparchy of Adigrat serves tens of thousands of Tigrayan Catholics, and includes parishes, schools, and religious orders operating in the region.[267][266] The liturgy is conducted in Geʽez, and priests are typically drawn from local Tigrayan communities.

Most Catholics in Tigray belong to the Irob people, an ethnic subgroup inhabiting the northeastern escarpments of the Tigray Region near the Eritrea–Ethiopia border. The Irob have historically maintained a distinct religious identity, preserving Catholic faith practices while participating in broader Tigrayan linguistic and cultural life.[268][269]

While Catholics remain a minority among Tigrayan Christians—who are overwhelmingly adherents of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church—they continue to play a significant role in religious, educational, and social life, particularly through schools, health centers, and monastic communities affiliated with the Eparchy of Adigrat.

Islam

While the majority of Tigrayans adhere to Christianity, a historically rooted minority of Muslims has long existed in the Tigray Region. The presence of Islam is traditionally linked to the First Hijrah in the 7th century CE, when early Muslims fled persecution and were welcomed by the Negus (Arabic: ٱلنَّجَاشِيُّ, al-Najāshī) of Abyssinia. The town of Negash, located in eastern Tigray, is considered one of the earliest Muslim settlements in Africa, and its restored Al Nejashi Mosque (the oldest in Ethiopia) remains a prominent religious site.[17][page needed]

Over the centuries, Sunni Muslim communities became integrated into the social and cultural fabric of Tigray, and they are now concentrated in border regions near Agame, Gulomahda, Shire, and Humera, where interaction with the Sudanese, Beja, and Saho was common.[270] Among them are the Jeberti, a Tigrinya-speaking Muslim group also present in Eritrea, often considered among the oldest Islamized populations in the Horn of Africa.[271][272] These communities traditionally follow Sunni Islam and maintain institutions such as madrasas, Sufi lodges, and local shrines.[273]

Despite being a minority, Tigrayan Muslims have generally coexisted peacefully with their Christian neighbors, although they experienced marginalization during periods when Orthodoxy was the state religion. In multi-religious cities like Adigrat and Shire, interfaith marketplaces, communal celebrations, and even intermarriage were historically not uncommon.[274][275]

In more recent times, since the adoption of Ethiopia’s current federal constitution has granted religious freedom, Muslim communities in Tigray have maintained their religious institutions and participate more actively in regional life, often in alignment with national Islamic councils rather than region-specific ethnic platforms.[274]

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Literature

Tigrinya literary traditions encompass both oral and written forms, with deep historical roots and continuing contemporary production. Oral literature includes proverbs, riddles, folktales, epic poems, and qǝne (poetic compositions), often performed in social gatherings, festivals, weddings and religious contexts, many of which transmit moral lessons, historical memory, and communal values.[276][277][278][279] Such oral forms serve as vehicles for moral instruction, historical commemoration, and communal identity, preserving accounts of local heroes, historical conflicts, and genealogies.[280]

Written literature in Tigray developed under the influence of Geʽez manuscript culture, with illuminated manuscripts, hagiographies, and theological treatises produced in monastic scriptoria from the Aksumite period onwards.[281] In religious life, Geʽez remains the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, used in the Divine Liturgy, hymns, and canonical readings. Tigrinya, however, plays a complementary role in sermons, hymn explanations, catechesis, religious education, and devotional publications intended for laypeople.[282][283] This combination ensures that while sacred tradition remains tied to the classical idiom, religious understanding is accessible in the vernacular.

However, Tigrinya really began to emerge as a literary language in the late 19th century, first through translations of religious texts, catechisms, and hymnals, later expanding to secular genres including newspapers, novels, poetry anthologies, political pamphlets, plays, and fiction.[284][285] The modern period saw the rise of prominent Tigrinya authors and poets (mostly from Eritrea though) whose works explore themes of identity, social change, and historical memory. Notable figures include Gebreyesus Hailu, author of one of the first Tigrinya novels Adefris (1945); Reesom Haile, celebrated for his innovative use of Tigrinya oral style in written poetry; and Alemseged Tesfai, known for plays and historical writing.[286][287] Modern print culture in Tigray is anchored by regional presses, with content ranging from news reporting to literary criticism and historical essays.[288][289]

Tigrinya literature in Tigray today spans a variety of genres—novels, short stories, historical essays, political commentary, and children’s literature—published through regional presses and broadcast via radio and television. Literary events and competitions, often held in urban centers such as Mekelle and Adwa, continue to foster the development of both standardized written Tigrinya and the creative adaptation of oral forms to contemporary contexts.[290][291]

Cultural events such as poetry recitals, historical commemorations, and theatrical performances reinforce the role of Tigrinya in the public sphere. Many works are performed in the standardized written register taught in schools, which helps bridge regional speech differences. At the same time, oral performance in local dialects remains vibrant, preserving community-specific styles and expressions.[292][293] In the diaspora, particularly in North America, Europe, and the Middle East, Tigrinya continues to be used in community associations, church services, satellite broadcasting, and online publications, sustaining cultural continuity across generations.[294][295]

Music

Up until the mid 20th century, Tigrinya music consisted mainly of religious and secular folk songs and dances.[296][297] Like Amharic music, Tigrayan music uses a variety of traditional instruments, such as the masenqo, a one-string bowed lute; the krar, a six-string lyre; the Meleket wind instrument, the washint flute often played by local village musicians called the Azmaris, the chira wata/wata (regional one-string bowed lutes), but also the kebero and Negarit (double-headed drum), the begena, a large ten-string lyre; is an important instrument solely devoted to the spiritual part of Church music.[298], and the tsenatsil (sistrum used in liturgy), but is characterized by distinctive rhythmic patterns, pentatonic scales, and call-and-response structures.[299][300][301]

Much of the traditional repertoire is closely tied to oral poetry, with singers improvising verses that recount local history, praise individuals, or comment on current events. Some genres, such as fǝqǝr (love songs) and mälkʷ’ä (panegyric songs), are performed at weddings and communal celebrations, while others commemorate historical battles or heroes.[302][303]

Religious music also plays a central role in Tigrayan cultural life, with the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church preserving a rich liturgical chant tradition in Geʽez, transmitted through the Zema system attributed to Saint Yared. These chants are performed by trained däbtära (cantors) using sistrums, drums, and choreographed movements during feast days and processions.[304][305]

However, Tigrayan culture is also famously known for its various dances. While guayla is the most widespread social dance among Tigrinya-speaking communities— performed at weddings, graduations, and communal celebrations across the region — Tigray also maintains a rich variety of distinct regional dance traditions.These local traditional dances often reflect significant regional diversity, each style rooted in local history and community life. In Tembien, the lively dance known as Awrs (or Awurs) is often performed during social gatherings and communal celebrations, with dancers circling to the beat of drums, flutes, clapping, and improvised verses that may praise, tease, or critique participants.[306] In Raya, dances such as Kuda and Saesiet/Tilhit are marked by spirited percussion, faster tempos, and expansive arm movements, reflecting cultural interactions with neighboring Oromo and Amhara communities.[307] In the highlands of Adwa and Axum, older guayla forms are preserved, characterized by restrained shoulder movements and circular formations, while the western lowland areas perform Shim Shim, Esthina, and Ehmbaza, incorporating Ululation, varied drum patterns, and call-and-response singing.[308][309][310]

In the modern era, the release of albums like Éthiopiques, Vol. 5, part of the 1970s Éthiopiques series, an album entirely devoted to Tigrinya music featuring both Tigrayan and Eritrean artists whose work blended traditional forms with emerging modern arrangements, played a notable role in bringing Tigrinya music to wider audiences.[311]

Afterwards, singers like Kiros Alemayehu or Gebretsadik Woldeyohannes rose to national prominence, further helping to popularize Tigrinya music in a largely Amharic-speaking Ethiopian music industry during the 1970s and 1980s. Meanwhile, people like Eyasu Berhe, Abebe Araya or to a lesser extent Amir Dawud became renowned for their patriotic and emotionally resonant songs, many of which reflected themes of struggle, unity, and sacrifice. In more recent years, artists such as Aziz Hagos, Ataklti Hailemichael, Abraham Gebremedhin, Eden Gebreselassie, Solomon Haile, Amanuel Yemane, Mahlet Gebregiorgis, Ephrem Amare or Dawit Nega were celebrated for their sophisticated fusion of traditional Tigrayan melodies with modern instrumentation, appealing to audiences across generations.[312][313][314]

Contemporary Tigrayan music is disseminated through radio, television, weddings, diaspora concerts, and online platforms, sustaining its popularity among younger generations both at home and abroad.[315]

Art

Tigrayan artistic traditions are deeply intertwined with the region’s religious, architectural, and historical heritage. The most prominent expressions are found in church art, particularly the rock-hewn churches of Tigray, whose interiors are decorated with murals depicting biblical scenes, saints, and liturgical motifs in a style influenced by both Aksumite and later Ethiopian Orthodox iconography.[316][317]

These wall paintings often combine bold colors, flattened perspective, and frontal figures characteristic of Ethiopian ecclesiastical art, adapted to local themes and saints venerated in Tigray.[318] Illuminated manuscripts have been another major artistic medium, produced for centuries in monastic scriptoria using parchment, natural pigments, and the Geʽez script. These works range from Gospel books and psalters to hagiographies, often featuring intricate harag (interlace) designs and miniature portraits of evangelists or saints.[319][320]

Tigrayan artisans are also known for metalwork, particularly elaborate hand crosses, processional crosses, and pendant crosses, often cast or carved in distinctive regional styles. These objects are both liturgical tools and symbols of personal devotion, sometimes decorated with geometric motifs and inscriptions in Geʽez.[321]

Stone carving has a long legacy in the region, dating back to the monumental architecture of the Kingdom of Aksum, with continued traditions in church construction, gravestones, and commemorative monuments.[322] Modern and contemporary Tigrayan artists, often trained in Mekelle or Addis Ababa, blend these historical influences with new media, producing works in painting, sculpture, and photography that engage with themes of heritage, resilience, and social change.[323]

Society

Tigrayans communities are marked by numerous social institutions with a strong networking of character, where relations are based on mutual rights and bonds. Thus, Tigrayan society is marked by a strong ideal of communitarianism and, especially in the rural sphere, by egalitarian principles. This does not exclude an important role of gerontocratic rules and in some regions such as the wider Adwa area, formerly the prevalence of feudal lords, who, however, still had to respect the local land rights.[9] Still now, Tigrayans communities are marked by numerous social institutions with a strong networking of character, where relations are based on mutual rights and bonds. Indeed, traditional Tigrayan society has historically been organized around a combination of kinship networks, village communities, and customary councils of elders.

One of the most significant and remarkable institutions is the shimagile (elders’ council), which functions as a respected body for mediating disputes, negotiating marriages, and resolving conflicts at the local level.[324][325] The process emphasizes consensus-building and reconciliation, with elders chosen for their moral standing, wisdom, and rhetorical skill.[326] Beyond dispute resolution, Tigrayan communities maintain various cooperative labor and mutual aid systems, such as debo (communal work parties for agricultural tasks), maḥbär (rotating feast associations, often linked to religious observances), and iqʷub (rotating credit associations).[327][328] These networks strengthen social solidarity and provide safety nets during hardship. In the urban context, the modern local government have taken over the functions of traditional associations. In most rural areas, however, traditional social organizations are fully in function. All members of such an extended family are linked by strong mutual obligations.[329] Villages are usually perceived as genealogical communities, consisting of several lineages.[9]

However, Tigrayans are sometimes described as “individualistic”, due to elements of competition and local conflicts.[330] This, however, rather reflects a strong tendency to defend one's own community and local rights against—then widespread—interferences, be it from more powerful individuals or the state. Historically, Tigrayan rural society was also shaped by land tenure systems, notably the rist system, in which land rights were inherited through descent from a common ancestor. This system reinforced lineage-based community organization and shaped patterns of settlement and local governance until the agrarian reforms of the 1970s.[331] While urbanization, education, and migration have introduced new social dynamics, many customary practices remain active in Tigray and among Tigrayan diaspora communities, adapted to contemporary settings while preserving their traditional emphasis on mutual responsibility and communal cohesion.[332][333]

Religious institutions, especially the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, continue to play a major role in community life, organizing festivals, providing moral guidance, and acting as centers for education and charity. In many rural areas, priests and monks are also influential mediators in local disputes, working alongside or within the shimagile system.[334]

Festivals and celebrations

Tigrayan social life is punctuated by major religious and cultural festivals that serve as key moments for community gathering, cultural expression, and intergenerational continuity. One of the most prominent is Ashenda, a festival celebrated annually in late August (around 16–21 Nehase in the Ethiopian calendar) by young women and girls. Originating in Tigray and parts of Eritrea, Ashenda is marked by participants wearing brightly embroidered dresses, bead necklaces, and floral headdresses, while singing and dancing in public spaces. Groups go from house to house performing songs—sometimes improvised—that blend praise, humor, and social commentary, receiving small gifts or food in return.[335][336] Ashenda is both a celebration of womanhood and community solidarity and, in some interpretations, linked to the Feast of the Assumption in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

Other important events include Hidar Tsion, the annual pilgrimage to the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum, held every 21 Hidar (30 November), which draws thousands of pilgrims from across Ethiopia and the diaspora.[337] Meskel (Finding of the True Cross, 27 September) is celebrated with bonfires (demera), processions, and church services, while Timket (Epiphany, 19 January) features outdoor processions, prayers, and the ceremonial blessing of water.[338] Many rural communities also observe local saints’ feast days, often involving church gatherings, communal meals, and music.

Cuisine

Tigrayan cuisine shares many features with the broader Ethiopian culinary tradition, while retaining distinctive local dishes and preparation styles. Thus, it characteristically consists of vegetable and often very spicy meat dishes, usually in the form of tsebhi (Tigrinya: ፀብሒ), a thick stew, served atop injera, a large sourdough flatbread made primarily from teff flour, which serves as both plate and utensil. [120] It is typically accompanied by a variety of stews (wat), including zigni (spicy beef or lamb stew), shiro (seasoned ground legumes), and alicha (milder vegetable or meat stews).[339][340]

Tigrayan cuisine is shaped by the fasting traditions of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which prescribe numerous periods each year when adherents abstain from animal products as well as a prohibition on the consumption of pork. For instance, meat and dairy products are not consumed on Wednesdays and Fridays, and also during the seven compulsory fasts. This has led to a rich repertoire of vegan dishes, including lentil, chickpea, and fava bean stews, vegetable wat, seasoned salads, and dishes made from fermented legumes such as shiro.[341] Eating around a shared food basket, mäsob (Tigrinya: መሶብ) is a custom in the Tigray region and is usually done so with families and guests. The food is eaten using no cutlery, using only the fingers (of the right hand) and sourdough flatbread to grab the contents on the bread.[342][343]

On top of that, the coffee ceremony is one of the most important daily and social rituals in Tigrayan culture, symbolizing hospitality, friendship, and respect. The process begins with washing and roasting green coffee beans over a charcoal brazier, their aroma wafting through the room to invite participants. The beans are then ground using a mortar and pestle and brewed in a traditional clay pot called a jebena. The ceremony typically involves three successive servings—abol (first), tona (second), and baraka (third)—each slightly weaker than the last, with conversation and sometimes the burning of incense accompanying the service.[344][345] The ceremony is often accompanied by snacks such as roasted barley, popcorn, or traditional bread, and serves as a central setting for discussing community matters and strengthening social bonds.

Regional dishes and drinks

T'ihlo (Tigrinya: ጥሕሎ, ṭïḥlo) is a dish originating from the historical Agame and Akkele Guzai provinces. The dish is unique to these parts of both countries, but is now slowly spreading throughout the entire region. T'ihlo is made using moistened roasted barley flour that is kneaded to a certain consistency. The dough is then broken into small ball shapes and is laid out around a bowl of spicy meat stew. A two-pronged wooden fork is used to spear the ball and dip it into the stew. It is often associated with communal gatherings and special occasions and is usually served with mes, a type of honey wine.[346][347]

Hilbet (Tigrinya: ሕልበት, romanized: ḥilbet) is a vegan cream dish, made from fenugreek, lentil and fava bean powder, typically served on injera with Silsi, (Tigrinya: ስልሲ) tomatoes cooked with berbere (Tigrinya: በርበረ).[348] Other regional foods include himbasha (Tigrinya: ሕምባሻ, romanized: ḥimbasha), a slightly sweet, round leavened bread often flavored with spices, chechebsa (Tigrinya: ጨጨብሳ, romanized: č̣eč̣ebsa), a pan-fried flatbread pieces coated in spiced butter or oil, and fit-fit (Tigrinya: ፍትፍት, romanized: fitfit), shredded injera mixed with stew or sauce.[349] Leafy greens such as hamli (Tigrinya: ሓምሊ, romanized: ḥamli) and wild herbs are commonly sautéed with garlic and spices, while dishes are seasoned with berbere (chili and spice blend) or mekelesha (Tigrinya: መከለሻ, romanized: mekeleša), an aromatic spice mix added at the end of cooking.

A notable feature of Tigrayan food culture is the production of traditional fermented beverages. The most widespread is Siwa (Tigrinya: ሰዋ, romanized: säwa), a home-brewed beer made from barley or other grains, flavored with dried leaves of the gesho plant used for bittering and fermentation.[350] Siwa is typically brewed in large clay vessels and served at social gatherings, weddings, and holidays, where it plays an important role in hospitality and community bonding.[351] Other beverages include tej (honey wine), often consumed during festive occasions, and arak’i (grain- or fruit-based distilled liquor).

Remove ads

Tigrayans vs. Tigrinya people: what's the difference?

Summarize

Perspective

Despite various attempts to deny the close kinship between the Tigrayans of northern Ethiopia and the Tigrinya people (Tigrinya: ብሄረ ትግርኛ, romanized: bəherä Təgrəñña) of central highland Eritrea, most historians, linguists, and anthropologists regard them as parts of a single ethnolinguistic group whose settlement spans the Eritrean–Tigrayan plateau. Both groups speak Tigrinya language, with only minor dialectal variation and full mutual intelligibility, and share a largely continuous cultural heritage rooted in highland society since at least the late Aksumite period.[352][353][354][355][356]

Historical and ethnographic sources consistently indicate that the Tigrinya-speaking populations of northern Ethiopia and central highland Eritrea have long been part of the same cultural and political sphere. Scholars such as Edward Ullendorff have identified them as the principal bearers of the historical traditions of ancient Abyssinia, while Donald N. Levine and Haggai Erlich trace their heritage directly to the Aksumite Empire.[357][358] During the medieval and early modern periods, the highlands north and south of the Mereb River often came under the authority of the same imperial rulers, such as Amda Seyon I and Zara Yaqob, whose domains encompassed both present-day Tigray and the Eritrean Highlands.[359][360] European observers such as the Portuguese Jesuit Jerónimo Lobo in the 1620s reinforced this perception by describing the inhabitants on both sides of the Mereb as speaking the same language and practising the same Orthodox Christian faith.[361] In the nineteenth century, the British explorer Henry Salt subdivided the kingdom of Tigré into various districts which included Baharanegash, noting that the northernmost district of Hamasien marked the edge of Tigré before the territory of the Beja.[362][363][364]

While cultural and linguistic commonalities are well-documented, scholars emphasise that modern political history has shaped distinct identities.[365][366][367] Italian colonial rule in Eritrea from the 1890s, followed by federation with Ethiopia and the subsequent independence struggle, fostered a strong Eritrean nationalist narrative that differentiates Biher-Tigrinya from their southern kin.[368][369][370] Professor Richard Reid notes that interpretations of the “trans-Mereb” relationship—referring to ties across the Mereb River dividing the Eritrean and Ethiopian highlands—are often polarised between Ethiopianist claims of long-standing unity and Eritrean revisionist assertions of historic autonomy.[371] He argues that while cycles of conflict and cooperation have marked relations over the centuries, there is no evidence of complete and permanent separation between these highland communities.

Anthropological and historical studies further show that political divergence has been shaped by state structures and nationalist mobilisation in the 20th century. Tekeste Negash links the emergence of distinct Eritrean identity to the colonial and post-colonial experience, whereas Tricia Redeker Hepner and Jordan Gebre-Medhin stress that shared kinship and cultural ties persisted despite the consolidation of separate political projects.[372][373][374][375][376][377][378] The prevailing scholarly view is that Tigrayans and Biher-Tigrinya form one broader ethnolinguistic group whose identities have diverged primarily due to differing political histories, rather than deep cultural or ethnic separation.[379][380][381][382][383][384][385][386][387][388][389][390][391]

Intermarriage and cross-border kinship have further reinforced the close ties between Tigrayans and Biher-Tigrinya. Many prominent figures in both communities have mixed ancestry or family origins on both sides of the Mereb River. Former Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi was born to an Eritrean mother from Adwa, while Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has Tigrayan paternal ancestry from the Tigray highlands.[392][393] Other examples include Eritrean independence leader Woldeab Woldemariam, whose family roots trace to both Eritrea and Tigray, and former Eritrean defence minister Sebhat Ephrem, born to parents of Tigrayan and Eritrean-Tigrinya descent.[394][395] Such familial connections illustrate the permeability of the modern border and the enduring social fabric linking the two groups.

In recent years, symbolic and grassroots initiatives have emerged to improve relations between the two communities. The 2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia peace agreement, reached between Abiy Ahmed and Isaias Afwerki, formally ended two decades of hostility and briefly reopened border crossings such as Zalambessa and Bure, enabling large-scale family reunions and renewed trade.[396] Although most crossings later closed, local actors have continued to pursue informal contact, with joint religious and cultural events reported in 2025 along the Mereb River frontier.[397]

Parallel to these reconciliatory gestures, ideological projects such as the Agazian movement have emerged in the diaspora and online spaces. First noted in the mid-2010s, the movement promotes a vision of a unified, Tigrinya language-speaking Orthodox Christian state across Eritrea and the Tigray Region, rooted in appeals to a shared Aksumite heritage.[398][399][400][401][402][403][404][405] While dismissed by many as a fringe or extremist current, others see it as symptomatic of unresolved debates over identity, political sovereignty, and the legacy of the trans-Mereb relationship.

Remove ads

Genetics

Summarize

Perspective

Autosomal ancestry

Genome-wide studies indicate that Tigrayans, like other northern Semitic-speaking groups, exhibit a roughly equal mixture of indigenous East African and West Eurasian ancestry.[406] Principal component analyses place Tigrayan samples between sub‑Saharan African and Middle Eastern/European reference populations, forming part of a broader “Habesha” cluster that also includes Amhara and Gurage.[407] A forensic study of Tigrayan individuals using 46 ancestry-informative Indels and 31 SNPs estimated ~50 % non‑African ancestry and confirmed their intermediate genetic position.[408] Another study showed that Tigrayan samples had (~50%) of a genetic component shared with European and Middle Eastern populations.[409]

Genetic studies suggest that the West Eurasian component entered the Horn of Africa during the late Holocene, roughly 2,500‑3,000 years ago, likely through movements across the Red Sea from South Arabia during the period associated with the Kingdom of Dʿmt and the formative phases of Aksumite civilization.[410] Comparative analyses indicate that Tigrayans are more closely related to Amhara and Eritrean Tigrinya speakers than to southern Ethiopian Semitic or Cushitic populations, highlighting the relative genetic continuity of the northern highlands.[411]