Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Tropical cyclones in 2003

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

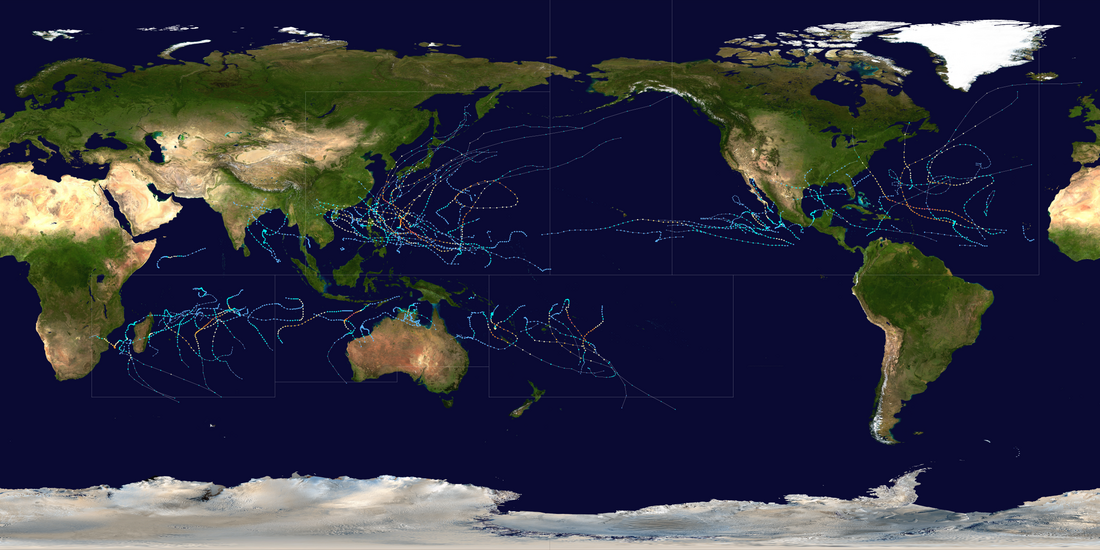

During 2003, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. During the year, a total of 129 systems formed with 85 of these developing further and were named by the responsible warning centre. The strongest tropical cyclone of the year was Cyclone Inigo, which was estimated to have a minimum barometric pressure of 900 hPa (26.58 inHg) and was tied with Cyclone Gwenda for being the most intense recorded cyclone in the Australian region in terms of pressure, with the possible exception of Cyclone Mahina.[1] So far, 26 Category 3 tropical cyclones formed, including six Category 5 tropical cyclones formed in 2003, tying 2021. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2003 (seven basins combined), as calculated by Colorado State University was 833 units.

Tropical cyclone activity in each basin is under the authority of an RSMC. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) is responsible for tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic and East Pacific. The Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC) is responsible for tropical cyclones in the Central Pacific. Both the NHC and CPHC are subdivisions of the National Weather Service. Activity in the West Pacific is monitored by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). Systems in the North Indian Ocean are monitored by the India Meteorological Department (IMD). The Météo-France located in Réunion (MFR) monitors tropical activity in the South-West Indian Ocean. The Australian region is monitored by five TCWCs that are under the coordination of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM). Similarly, the South Pacific is monitored by both the Fiji Meteorological Service (FMS) and the Meteorological Service of New Zealand Limited. Other, unofficial agencies that provide additional guidance in tropical cyclone monitoring include the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).

Remove ads

Global conditions and hydrological summary

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2021) |

The ENSO in this year was mostly neutral.

Summary

Systems

Summarize

Perspective

January

In January, the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which allows for the formation of tropical waves, is located in the Southern Hemisphere, remaining there until May.[2] This limits Northern Hemisphere cyclone formation to comparatively rare non-tropical sources.[3] In addition, the month's climate is also an important factor. In the Southern Hemisphere basins, January, at the height of the austral summer, is the most active month by cumulative number of storms since records began. Of the four Northern Hemisphere basins, none is very active in January, as the month is during the winter, but the most active basin is the Western Pacific, which occasionally sees weak tropical storms form during the month.[4][5]

January was active, with eight tropical cyclones, six of which were named. Tropical Storm Delfina from the South-West Indian Ocean persisted into 2003 and made landfall near Angoche in eastern Mozambique, killing fifty and causing some damages. The first storm of the year was an unnamed tropical cyclone, and the number of deaths and damage caused in Australia is unknown. Cyclone Ami caused widespread damage in Fiji, resulting in the deaths of fourteen people and $51.4 million in damage. Tropical Storm Yanyan in the Western Pacific Ocean formed without affecting any areas. Cyclone Beni became the most intense tropical cyclone of the month, with maximum sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph) and a minimum pressure of 920 mbar (hPa). Beni killed one person in Queensland, Australia, and damages totaled US$12 million.

February

In terms of activity, February is normally similar to January, with activity effectively restricted to the Southern Hemisphere excepting the rare Western Pacific storm. In fact, in the Southern Hemisphere, due to the monsoon being at its height,[4] February tends to see more formation of strong tropical cyclones than January despite seeing marginally fewer overall storms.[16] In the Northern Hemisphere, February is the least active month, with no Eastern or Central Pacific tropical cyclones[17] and only one Atlantic tropical cyclone having ever formed in the month.[18] Even in the Western Pacific, February activity is low: in 2003, the month had never seen any typhoon-strength storms, with the first being 2015's Typhoon Higos.[19][20]

February was very active, with eight tropical cyclones, seven of which were named. Cyclone Gerry in the south-west Indian Ocean caused moderate damage in parts of Tromelin Island and Mauritius. Cyclone Dovi, the most intense cyclone of the month, did not cause damage in any areas. Cyclone Japhet caused damage in southeastern Africa, killing 26 people. The month ended with Cyclone Graham, which caused property damage in Australia, killing only one person.

March

During March, activity tends to be lower than in preceding months. In the Southern Hemisphere, the peak of the season has normally already passed, and the monsoon has begun to weaken, decreasing cyclonic activity, however, the month often sees more intense tropical cyclones than January or February.[4][16] Meanwhile, in the Northern Hemisphere basins, sea surface temperatures are still far too low to normally support tropical cyclogenesis. The exception is the Western Pacific, which usually sees its first storm, often a weak depression, at some point between January and April.[19]

March was slightly active, with six tropical cyclones forming, five of which were named.[35] The season began with storms Harriet and Erica in the Australian region, one of which crossed into the South Pacific becoming a severe Category 5 tropical cyclone with maximum winds of 215 km/h (130 mph) and a minimum pressure of 915 millibars. The most intense tropical cyclone of the month, as well as of the basin, was Cyclone Kalunde, which became the first Category 5 tropical cyclone of the year. Kalunde caused widespread damage on Rodrigues Island, amounting to US$3.15 million. The month ended abruptly with Cyclone Eseta in the South Pacific Ocean, which caused minimal damage in Fiji.

April

The factors that begin to inhibit Southern Hemisphere cyclone formation in March are even more pronounced in April, with the average number of storms formed being hardly half that of March. However, even this limited activity exceeds the activity in the Northern Hemisphere, which is rare, with the exception of the Western Pacific basin. All Pacific typhoon seasons between 1998 and 2016 saw activity between January and April, although many of these seasons saw only weak tropical depressions. By contrast, only two Atlantic hurricane seasons during those years saw tropical cyclone formation during that period.[18] With the combination of the decreasing temperatures in the Southern Hemisphere and the still-low temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere, April and May tend to be the least active months worldwide for tropical cyclone formation.[45]

April was moderately active in terms of named storms, with seven tropical cyclones, five of which were named. The month began with the formation of Cyclone Inigo, which became the most intense tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Australian region, tying with Cyclone Gwenda four years earlier. Inigo caused devastating damage in Indonesia, killing around 60 people and causing US$12 million in damage. Typhoon Kujira in the Western Pacific Ocean lasted only sixteen days and affected parts such as Micronesia, then Taiwan and Japan, causing minimal damage with three fatalities. The month ended with the formation of Tropical Storm Ana in the Atlantic Ocean, which, despite its early formation, caused minimal damage with two fatalities.

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Remove ads

Global effects

Summarize

Perspective

There are a total of seven tropical cyclone basins that tropical cyclones typically form in this table, data from all these basins are added.[121]

- The wind speeds for this tropical cyclone/basin are based on the Saffir Simpson Scale which uses 1-minute sustained winds.

- Only systems that formed either before or on December 31, 2003 are counted in the seasonal totals.

- Only systems that formed either on or after January 1, 2003 are counted in the seasonal totals.

- The wind speeds for this tropical cyclone are based on Météo-France, which uses wind gusts.

- The sum of the number of systems in each basin will not equal the number shown as the total. This is because when systems move between basins, it creates a discrepancy in the actual number of systems.

Remove ads

Notes

- According to the JTWC, Cyclone Heta developed as a tropical disturbance on December 25, 2003, and was officially named on January 2, 2004, which is not included in this list.

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads