Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

2004 Spanish general election

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

A general election was held in Spain on Sunday, 14 March 2004, to elect the members of the 8th Cortes Generales under the Spanish Constitution of 1978. All 350 seats in the Congress of Deputies were up for election, as well as 208 of 259 seats in the Senate. It was held concurrently with the 2004 Andalusian regional election.

Since 2000, the ruling People's Party (PP) had governed with an absolute majority in the Congress of Deputies which allowed it to renegue from its previous agreements with peripheral nationalist parties. This period saw sustained economic growth, but the controversial management—and, at times, attempted cover-up—of a number of crises affected Aznar's government standing and fostered perceptions of arrogance: this included the "Gescartera case", the Prestige oil spill and the Yak-42 crash. A reform of unemployment benefits led to a general strike in 2002, and the unpopular decision to intervene in the Iraq War sparked massive protests across Spain. The incumbent prime minister, José María Aznar, had renounced to seek a third term, being replaced as party candidate by the first deputy prime minister, Mariano Rajoy.

The electoral outcome was heavily influenced by the Madrid train bombings on 11 March, which saw Aznar's government blaming the Basque separatist ETA for the attacks in spite of mounting evidence suggesting Islamist authorship. The ruling PP was accused by the opposition of staging a disinformation campaign to prevent the blame on the bombings being linked to Spain's involvement in Iraq. Results saw the opposition Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) under new leader José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero securing an unprecedented 11 million votes, with a net gain of 39 seats up to 164, whereas the PP (which had been predicted by opinion polls to secure a diminished but still commanding victory) lost 35 seats in the worst defeat for a sitting Spanish government up to that point since 1982. Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) benefitted from the impact of the "Carod case"—the revelation that party leader Josep-Lluís Carod-Rovira had held a meeting with ETA shortly after joining the new Catalan regional government of Pasqual Maragall—which gave the party publicity to the detriment of Convergence and Union (CiU). The 75.7% voter turnout was among the highest since the Spanish transition to democracy, with no subsequent general election having exceeded such figure. The number of votes cast, at 26.1 million votes, remained the highest figure in gross terms for any Spanish election until April 2019.[1][2][3]

The election result was described by some media as an "unprecedented electoral upset".[4] Perceived PP abuses and public rejection at Spain's involvement in Iraq were said to help fuel a wave of discontent against the incumbent ruling party, with Aznar's mismanagement of the 11M bombings serving as the final catalyst for change to happen.[5][6] Zapatero announced his will to form a minority PSOE government, seeking the parliamentary support of other parties once elected.[7]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

The People's Party (PP) secured an absolute majority of seats for the first time ever in the 2000 general election, which allowed Prime Minister José María Aznar to be re-elected for a second term in office.[8][9] The defeat of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), which obtained its worst result since 1979, prompted the resignation of party leader Joaquín Almunia and a leadership contest being triggered,[10][11] in which dark horse candidate José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero emerged as new leader in a surprise victory over President of Castilla–La Mancha José Bono.[12]

With unemployment remaining low under Spanish standards and the economy growing at a steady pace, Aznar's government continued its policy of economic liberalization in a wide range of activities (including several sectors which had been subject to state monopoly): business hours, gasoline, electricity, gas, taxation, health, telecommunications, land, technology policy, professional associations and competition.[13] This policy, together with the continued inflow of European funds, provided the State with extraordinary revenues that contributed to curb the fiscal deficit and reduce the level of public debt; however, the Spanish government's overreliance on housing as an economic engine generated a property bubble due to the purpose of many purchases being to speculate.[14] Further, the cash rounding resulting from the introduction of the euro on 1 January 2002 led to a rise in inflation.[15][16]

Domestically, Aznar had to deal with the impact of the mad cow crisis early into its second term, with a bovine spongiform encephalopathy outbreak in Spain resulting in five dead.[17][18] In the summer of 2001, it was unveiled that the Gescartera investment company had engaged in profit-making activities by defrauding its clients through the misappropriation of funds and influence peddling, leading to the loss of around Pts 18 billion affecting up to 4,000 small investors; the scandal saw the resignations of then Secretary of State for the Treasury Enrique Giménez-Reyna—who was a brother to Gescartera's chairwoman—and the president of the National Securities Market Commission (CNMV).[19][20] An attempt by the government to reform unemployment benefits and other working conditions through decree-law led to a general strike in 2002, forcing the proposal to be watered down;[21][22] the Constitutional Court of Spain would end up ruling the proposed reform as unlawful in 2007.[23]

Terrorism was a major issue during Aznar's second tenure as prime minister, as the ETA group conducted major attacks such as the killings of former health minister Ernest Lluch and Supreme Court judge Francisco Querol Lombardero, among others. In response, PP and PSOE signed an "Anti-Terrorist Pact" as a show of unity against terrorism,[24] and a new Law of Political Parties was approved in 2002 which allowed the banning of the Batasuna party over its links and support to ETA's actions.[25][26] Concurrently, the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) under Lehendakari Juan José Ibarretxe sought to resolve the Basque conflict through a more pro-sovereigntist position, tabling an initiative—the Ibarretxe Plan—to totally reform the Basque Statute of Autonomy by proposing a free association of the Basque Country with Spain on an equal footing, including a right to self-determination.[27]

This period also saw the controversial management of a number of crises by the Aznar government, receiving criticism over the perceived cover-up nature of its actions—frequently through denialism and diffusion of responsibility—which negatively affected its public standing and fostered a perception of arrogance in the exercise of power.[28][29] The Prestige oil spill in November 2002 saw extensive damage to the coast of Galicia, with the Spanish government being criticized for its decision to tow the ailing wreck out to sea—where it split in two—rather than allow it to take refuge in a sheltered port, which was seen as a major contributing factor to the scale of the disaster.[30] The Yak-42 crash in May 2003, with the death of all 75 occupants, saw a misidentification of bodies (with some remains being returned to the wrong relatives and others being mixed-up) as well as questions on the plane's poor condition.[31]

At the international level, the election of George W. Bush as new U.S. president and the 9/11 attacks saw Spain aligning closer to the United States, with Aznar voicing his support to Bush's missile shield, his "war on terror" and the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan,[32][33] in exchange for U.S. support to Spain's fight against ETA's terrorism.[34] Spain's rapprochement to the United States and the United Kingdom—under then Prime Minister Tony Blair—culminated in the Azores Summit on 16 March 2003, which led to the subsequent invasion of Iraq under the alleged aim of disarming Saddam Hussein's regime of "weapons of mass destruction" (WMDs). Aznar's decision to intervene in the Iraq War proved highly unpopular,[35] sparking massive anti-war protests across the country.[36][37] The Perejil Island crisis in July 2002, which saw a squad of the Royal Moroccan Navy temporarily occupying the uninhabited island, was resolved after a bloodless military intervention by the Spanish military.[38]

Aznar had emphasized a number of times that he only wished to serve as prime minister for two consecutive terms.[39][40] In the 2002 PP congress, he confirmed his decision not to stand for re-election,[41][42] and in April 2002 he announced that he would be withdrawing from politics altogether in the next general election.[43] Among the prospective successors were Jaime Mayor Oreja—who vacated his post of interior minister in order to run as lehendakari candidate in the 2001 Basque regional election—first deputy prime minister Mariano Rajoy and second deputy prime minister and economy and finance minister Rodrigo Rato.[44] Rato reportedly rejected twice being singled out as Aznar's successor,[45] resulting in Rajoy being selected for the position in September 2003.[46][47]

Despite the growing unpopularity of Aznar's government, the PP was able to come out of the 2003 local and regional elections with limited losses.[48][49] The outcome of the regional election in Madrid was significant as it hinted at the formation of a left-wing government in Spain's capital region; however, the Tamayazo scandal—which saw two PSOE MPs refusing to follow party discipline—prevented the regional PSOE leader from becoming president and forced a repeat election in October, which the PP won.[50][51] Shortly thereafter, the November 2003 Catalan regional election saw the Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSC)—PSOE's sister party in Catalonia—oust Convergence and Union (CiU) from the Catalan government after 23 years of uninterrupted rule, with a "tripartite" cabinet between PSC, Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and Initiative for Catalonia Greens (ICV) being formed under Pasqual Maragall.[52][53]

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

Under the 1978 Constitution, the Spanish Cortes Generales were envisaged as an imperfect bicameral system.[54][55] The Congress of Deputies had greater legislative power than the Senate, having the ability to vote confidence in or withdraw it from a prime minister and to override Senate vetoes by an absolute majority of votes.[56] Nonetheless, the Senate possessed a limited number of functions—such as ratification of international treaties, authorization of collaboration agreements between autonomous communities, enforcement of direct rule, regulation of interterritorial compensation funds, and its role in constitutional amendment and in the appointment of members to the Constitutional Court and the General Council of the Judiciary—which were not subject to the Congress's override.[57]

Electoral system

Voting for each chamber of the Cortes Generales was on the basis of universal suffrage, which comprised all nationals over 18 years of age and in full enjoyment of their political rights, provided that they were not sentenced—by a final court ruling—to deprivation of the right to vote, nor being legally incapacitated.[58][59]

The Congress of Deputies was entitled to a minimum of 300 and a maximum of 400 seats, with the electoral law setting its size at 350. 348 members were elected in 50 multi-member constituencies—corresponding to the provinces of Spain, with each being allocated an initial minimum of two seats and the remaining 248 being distributed in proportion to their populations—using the D'Hondt method and a closed list proportional voting system, with an electoral threshold of three percent of valid votes (which included blank ballots) being applied in each constituency. The two remaining seats were allocated to Ceuta and Melilla as single-member districts and elected using plurality voting.[60][61] The use of the electoral method resulted in a higher effective threshold based on the district magnitude and the distribution of votes among candidacies.[62]

As a result of the aforementioned allocation, each Congress multi-member constituency was entitled the following seats:[63]

208 seats in the Senate were elected using an open list partial block voting system: in constituencies electing four seats, electors could vote for up to three candidates; in those with two or three seats, for up to two candidates; and for one candidate in single-member districts. Each of the 47 peninsular provinces was allocated four seats, whereas for insular provinces, such as the Balearic and Canary Islands, districts were the islands themselves, with the larger (Mallorca, Gran Canaria and Tenerife) being allocated three seats each, and the smaller (Menorca, Ibiza–Formentera, Fuerteventura, La Gomera, El Hierro, Lanzarote and La Palma) one each. Ceuta and Melilla elected two seats each. Additionally, autonomous communities could appoint at least one senator each and were entitled to one additional senator per each million inhabitants.[64][65][66]

The law did not provide for by-elections to fill vacated seats; instead, any vacancies that occurred after the proclamation of candidates and into the legislative term were to be covered by the successive candidates in the list and, when required, by the designated substitutes.[67]

Eligibility

Spanish citizens of age and with the legal capacity to vote could run for election, provided that they were not sentenced to imprisonment by a final court ruling nor convicted, even if by a non-final ruling, to forfeiture of eligibility or to specific disqualification or suspension from public office under particular offences: rebellion, terrorism or other crimes against the state. Other causes of ineligibility were imposed on the following officials:[68][69]

- Members of the Spanish royal family and their spouses;

- The holders of a number of positions: the president and members of the Constitutional Court, the General Council of the Judiciary, the Supreme Court, the Council of State, the Court of Auditors and the Economic and Social Council; the Ombudsman; the State's Attorney General; high-ranking members—undersecretaries, secretaries-general, directors-general and chiefs of staff—of Spanish government departments, the Office of the Prime Minister, the Social Security and other government agencies; government delegates and sub-delegates in the autonomous communities; the director-general of RTVE; the director of the Electoral Register Office; the governor and deputy governor of the Bank of Spain; the chairs of the Official Credit Institute and other official credit institutions; and members of electoral commissions and of the Nuclear Safety Council;

- Heads of diplomatic missions in foreign states or international organizations (ambassadors and plenipotentiaries);

- Judges and public prosecutors in active service;

- Personnel of the Armed Forces (Army, Navy and Air Force) and law enforcement corps in active service.

Other causes of ineligibility for both chambers were imposed on a number of territorial-level officers in the aforementioned categories—during their tenure of office—in constituencies within the whole or part of their respective area of jurisdiction, as well as employees of foreign states and members of regional governments.[68][69] Incompatibility provisions extended to the president of the Competition Defence Court; members of RTVE's board and of the offices of the prime minister, the ministers and the secretaries of state; government delegates in port authorities, hydrographic confederations and toll highway concessionary companies; presidents and other high-ranking members of public entities, state monopolies, companies with majority public participation and public saving banks; as well as the impossibility of simultaneously holding the positions of deputy and senator or regional legislator.[70]

The electoral law allowed for parties and federations registered in the interior ministry, coalitions and groupings of electors to present lists of candidates. Parties and federations intending to form a coalition ahead of an election were required to inform the relevant electoral commission within ten days of the election call, whereas groupings of electors needed to secure the signature of at least one percent of the electorate in the constituencies for which they sought election, disallowing electors from signing for more than one list of candidates.[71]

Election date

The term of each chamber of the Cortes Generales—the Congress and the Senate—expired four years from the date of their previous election, unless they were dissolved earlier.[72] The election decree was required to be issued no later than the twenty-fifth day prior to the date of expiry of parliament and published on the following day in the Official State Gazette (BOE), with election day taking place on the fifty-fourth day from publication.[73] The previous election was held on 12 March 2000, which meant that the chambers' terms would have expired on 12 March 2004. The election decree was required to be published in the BOE no later than 17 February 2004, with the election taking place on the fifty-fourth day from publication, setting the latest possible date for election day on Sunday, 11 April 2004.

The prime minister had the prerogative to propose the monarch to dissolve both chambers at any given time—either jointly or separately—and call a snap election, provided that no motion of no confidence was in process, no state of emergency was in force and that dissolution did not occur before one year had elapsed since the previous one.[74] Additionally, both chambers were to be dissolved and a new election called if an investiture process failed to elect a prime minister within a two-month period from the first ballot.[75] Barring this exception, there was no constitutional requirement for simultaneous elections to the Congress and the Senate. Still, as of 2025, there has been no precedent of separate elections taking place under the 1978 Constitution.

On 9 January 2004, it was announced that the general election would be held in March,[76][77] with the election date being agreed with Andalusian president Manuel Chaves to make it being held concurrently with the 2004 Andalusian regional election.[78]

The Cortes Generales were officially dissolved on 20 January 2004 after the publication of the dissolution decree in the BOE, setting the election date for 14 March and scheduling for both chambers to reconvene on 2 April.[63]

Remove ads

Parliamentary composition

Summarize

Perspective

The tables below show the composition of the parliamentary groups in both chambers at the time of dissolution.[79][80]

Remove ads

Parties and candidates

Summarize

Perspective

Below is a list of the main parties and electoral alliances which contested the election:

The Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSC), Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and Initiative for Catalonia Greens (ICV) agreed to continue with the Catalan Agreement of Progress alliance for the Senate with the inclusion of United and Alternative Left (EUiA).[103] In the Balearic Islands, PSM–Nationalist Agreement (PSM–EN), United Left of the Balearic Islands (EUIB), The Greens of the Balearic Islands (EVIB) and ERC formed the Progressives for the Balearic Islands alliance.[104] A proposal for an all-left electoral alliance for the Senate in the Valencian Community, comprising the PSOE, United Left of the Valencian Country (EUPV) and the Valencian Nationalist Bloc (BNV), was ultimately discarded.[105][106][107]

Remove ads

Campaign

Summarize

Perspective

Party slogans

Madrid train bombings

During the peak of Madrid rush hour on the morning of Thursday, 11 March 2004, ten explosions occurred aboard four commuter trains (cercanías) between Alcalá de Henares and Atocha station, killing 193 people and injuring around 2,500, in what would become the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of Spain and the deadliest in Europe since the Lockerbie bombing in 1988.[119][120]

In response to the bombings, political parties announced the suspension of their campaigns.[121] At first, politicians from all parties—including the PSOE,[122] CiU,[123] IU,[124] PNV,[125] and ERC[126]—blamed ETA. The Spanish government immediately claimed ETA's responsibility and dismissed any other authorship, with Prime Minister José María Aznar personally phoning newspaper editors to uphold this version at noon on the day of the attacks.[127][128] Aznar's government also sent messages to all Spanish embassies abroad ordering that they uphold the version that ETA was responsible.[129] However, ETA denied any involvement in the attacks,[130] and evidence obtained by police and security forces started pointing to an Islamist authorship by the afternoon of 11 March; particularly, the discovery of a van containing a tape with Qur'anic verses and an al-Qaeda claim of responsibility being published by the Al-Quds Al-Arabi London Arabic-language newspaper.[131][132] The government insisted on the ETA's authorship claim into 12 March—despite the discovery that day of a detonator that did not match those used by ETA[133]—and, on the eve of the election, PP candidate Mariano Rajoy claimed in a El Mundo interview that he had "the moral conviction that it was ETA".[134] By that point, however, interior minister Ángel Acebes had acknowledged that the government had not "closed off any line of investigation".[127]

In the days previous to the election, millions of Spaniards took to the streets protesting against the bombings in massive demonstrations across the country to condem terrorism and express solidarity for the victims,[135] but also to demand answers about the attacks—with cabinet members at the Madrid demonstration on 12 March being greeted with booing and shouts of "Who did it?"—amid growing concerns that the government was deliberately concealing evidence from the public.[136][137]

During the day of election silence on 13 March, spontaneous cell phone messages ending in the catchphrase pásalo (Spanish for "pass it on") invoked thousands to unofficial demonstrations in front of the ruling PP's headquarters in major cities throughout the country, blaming the attacks on Aznar's decision to engage in the Iraq War (with shouts of "your war, our dead" and "murderers").[138][139][140] On the evening of that day, the Spanish government announced the arrest of three Moroccans and two Indians,[127] concurrently with the discovery of a videotape from a purported al-Qaeda official claiming responsibility for the attacks.[141] This stirred further anti-government unrest throughout the country demanding to "being told the truth",[142][143] which prompted Rajoy to issue a statement denouncing that the "illegal" protests constituted "undemocratic acts of pressure on tomorrow's election", and accusing the opposition PSOE of staging them.[144] PSOE's campaign manager Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba replied in a press briefing, rejecting Rajoy's accusations and condemning the government's handling of the crisis, revealing that party leaders had been aware for many hours that the main line of police investigation into the attacks was now pointing to Islamism—information which the government withheld from its public statements—and that they were never going to "use terrorism for political purposes", while also claiming that "Spanish citizens deserve a government that does not lie to them, a government that always tells them the truth".[145] By the end of the night, the entire opposition was accusing the PP government of manipulating and concealing information on the bombings.[146]

In the ensuing years, several sources would claim that the prospective electoral influence of the bombings was discussed in an emergency government meeting held on 11 March, which focused on the massacre's authorship: if ETA was proven to be responsible, it would favour the PP's hardline campaign on terrorism in a rally 'round the flag effect, but if an Islamist group appeared to have caused the blasts, people would link them to the Spanish intervention in the Iraq War and blame the PP for earning Spain enemies. Along these lines, a statement allegedly made in the meeting—and attributed by some accounts to Aznar's chief advisor, Pedro Arriola—claimed that "if it was ETA, we'll win [by a landslide]; if it was the Islamists, the PSOE shall win".[j][147][148]

Remove ads

Opinion polls

Results

Congress of Deputies

Senate

Maps

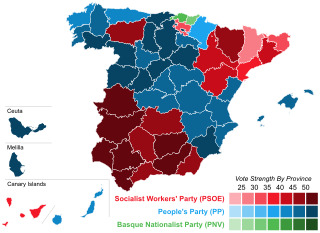

- Election results by constituency (Congress).

- Vote winner strength by constituency (Congress).

- Vote winner strength by autonomous community (Congress).

Remove ads

Aftermath

Government formation

Remove ads

Notes

- Results for PSOE–p (34.2%, 125 deputies) and Extremaduran Coalition (0.0%, 0 deputies) in the 2000 Congress election.

- Cristina Alberdi, former PSOE legislator.[82]

- The percentage of blank ballots is calculated over the official number of valid votes cast, irrespective of the total number of votes shown as a result of adding up the individual results for each party.

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads