Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Age of Discovery

Period of European global exploration From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Age of Discovery (c. 1418 – c. 1620),[1] also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which seafarers from European countries explored, colonized, and conquered regions across the globe. The Age of Discovery was a transformative period when previously isolated parts of the world became connected to form the world-system, and laid the groundwork for globalization. The extensive overseas exploration, particularly the opening of maritime routes to the East Indies and European colonization of the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese, later joined by the English, French and Dutch, spurred international global trade. The interconnected global economy of the 21st century has its origins in the expansion of trade networks during this era.

This may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 17,000 words. (June 2024) |

The exploration created colonial empires and marked an increased adoption of colonialism as a government policy in several European states. As such, it is sometimes synonymous with the first wave of European colonization. This colonization reshaped power dynamics causing geopolitical shifts in Europe and creating new centers of power beyond Europe. Having set human history on the global common course, the legacy of the Age still shapes the world today.

European oceanic exploration started with the maritime expeditions of Portugal to the Canary Islands in 1336,[2][3] and with the Portuguese discoveries of the Atlantic archipelagos of Madeira and Azores, the coast of West Africa in 1434, and the establishment of the sea route to India in 1498 by Vasco da Gama, which initiated the Portuguese maritime and trade presence in Kerala and the Indian Ocean.[4][5] Spain sponsored and financed the transatlantic voyages of Christopher Columbus, which from 1492 to 1504 marked the start of colonization in the Americas, and the expedition of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan to open a route from the Atlantic to the Pacific, which later achieved the first circumnavigation of the globe between 1519 and 1522. These Spanish expeditions significantly impacted European perceptions of the world. These discoveries led to numerous naval expeditions across the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, and land expeditions in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia that continued into the 19th century, followed by Polar exploration in the 20th century.

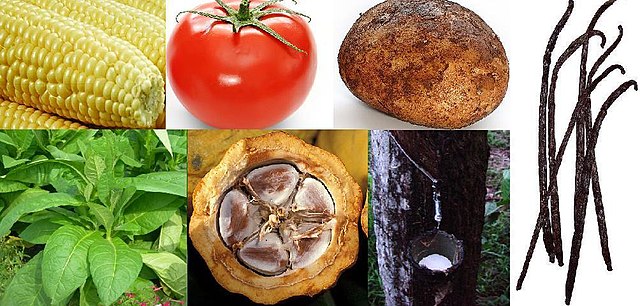

European exploration initiated the Columbian exchange between the Old World (Europe, Asia, and Africa) and New World (Americas). This exchange involved the transfer of plants, animals, human populations (including slaves), communicable diseases, and culture across the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. The Age of Discovery and European exploration involved mapping the world, shaping a new worldview and facilitating contact with distant civilizations. The continents drawn by European mapmakers developed from abstract "blobs" into the outlines more recognizable to us.[6] Simultaneously, the spread of new diseases, especially affecting American Indians, led to rapid declines in some populations. The era saw widespread enslavement, exploitation and military conquest of indigenous peoples, concurrent with the growing economic influence and spread of Western culture, science and technology leading to a faster-than-exponential population growth world-wide.

Remove ads

Concept

Summarize

Perspective

The concept of discovery has been scrutinized, critically highlighting the history of the core term of this periodization.[7] The term "age of discovery" is in historical literature and still commonly used. J. H. Parry, calling the period the Age of Reconnaissance, argues that not only was the era one of European explorations, but it also produced the expansion of geographical knowledge and empirical science. "It saw also the first major victories of empirical inquiry over authority, the beginnings of that close association of science, technology, and everyday work which is an essential characteristic of the modern western world."[8] Anthony Pagden draws on the work of Edmundo O'Gorman for the statement that "For all Europeans, the events of October 1492 constituted a 'discovery'. Something of which they had no prior knowledge had suddenly presented itself to their gaze."[9] O'Gorman argues that the physical encounter with new territories was less important than the Europeans' effort to integrate this new knowledge into their worldview, what he calls "the invention of America".[10] Pagden examines the origins of the terms "discovery" and "invention". In English, "discovery" and its forms in romance languages derive from "disco-operio, meaning to uncover, to reveal, to expose to the gaze", what was revealed existed previously.[11] Few Europeans during the period used the term "invention" for the European encounters, with the exception of Martin Waldseemüller, whose map first used the term "America".[12]

A central legal concept of the discovery doctrine, expounded by the US Supreme Court in 1823, draws on assertions of European powers' right to claim land during their explorations. The concept of "discovery" has been used to enforce colonial claiming and discovery, but has been challenged by indigenous peoples[13] and researchers.[14] Many indigenous peoples have fundamentally challenged the concept of colonial claiming of "discovery" over their lands and people, as forced and negating indigenous presence.

The period alternatively called the Age of Exploration, has been scrutinized through reflections on the exploration. Its understanding and use, has been discussed as being framed and used for colonial ventures, discrimination and exploitation, by combining it with concepts such as the frontier (as in Frontier Thesis) and manifest destiny,[15] up to the contemporary age of space exploration.[16][17][18][19] Alternatively, the term contact, as in first contact, has been used to shed more light on the age of discovery and colonialism, using the alternative names of Age of Contact[20] or Contact Period,[21] discussing it as an "unfinished, diverse project".[22][23]

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

The Portuguese began systematically exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa in 1418, under the sponsorship of Prince Henry the Navigator. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias reached the Indian Ocean by this route.[24]

In 1492, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain funded Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus's (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo) plan to sail west to reach the Indies, by crossing the Atlantic. Columbus encountered a continent uncharted by Europeans (though it had been explored and temporarily colonized by the Norse 500 years earlier).[25] Later, it was called America after Amerigo Vespucci, a trader working for Portugal.[26][27] Portugal quickly claimed those lands under the terms of the Treaty of Alcáçovas, but Castile was able to persuade the Pope, who was Castilian, to issue four papal bulls to divide the world into two regions of exploration, where each kingdom had exclusive rights to claim newly discovered lands. These were modified by the Treaty of Tordesillas, ratified by Pope Julius II.[28][29]

In 1498, a Portuguese expedition commanded by Vasco da Gama reached India by sailing around Africa, opening up direct trade with Asia.[30] While other exploratory fleets were sent from Portugal to northern North America, Portuguese India Armadas also extended this Eastern oceanic route, touching South America and opening a circuit from the New World to Asia (starting in 1500 by Pedro Álvares Cabral), and explored islands in the South Atlantic and Southern Indian Oceans. The Portuguese sailed further eastward, to the valuable Spice Islands in 1512, landing in China one year later. Japan was reached by the Portuguese in 1543. In 1513, Spanish Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama and reached the "other sea" from the New World. Thus, Europe first received news of the eastern and western Pacific within a one-year span around 1512. East and west exploration overlapped in 1522, when a Spanish expedition sailing westward, led by Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan (and, after his death in what is now the Philippines, by navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano), completed the first circumnavigation of the world.[31] Spanish conquistadors explored the interior of the Americas, and some of the South Pacific islands. Their main objective was to disrupt Portuguese trade in the East.

From 1495, the French, English, and Dutch entered the race of exploration, after learning of Columbus' exploits, defying the Iberian monopoly on maritime trade by searching for new routes. The first expedition was led by John Cabot in 1497 to the north, in the service of England, followed by French expeditions to South America and later to North America. Later expeditions went to the Pacific Ocean around South America, and eventually by following the Portuguese around Africa, into the Indian Ocean; discovering Australia in 1606, New Zealand in 1642, and Hawaii in 1778. From the 1580s to the 1640s, Russians explored and conquered almost the whole of Siberia, and claimed Alaska in the 1730s.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Rise of European trade

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire largely severed the connection between Europe and lands further east, Christian Europe was largely a backwater compared to the Arab world, which conquered and incorporated large territories in the Middle East and North Africa. The Christian Crusades to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims were not a military success, but they did bring Europe into contact with the Middle East and the valuable goods manufactured or traded there. From the 12th century, the European economy was transformed by the interconnecting of river and sea trade routes.[32]: 345

Before the 12th century, an obstacle to trade east of the Strait of Gibraltar, which connected the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Ocean, was Muslim control of territory, including the Iberian Peninsula, as well as the trade monopolies of Christian city-states on the Italian Peninsula, especially Venice and Genoa. Economic growth of Iberia followed the Christian reconquest of Al-Andalus in what is now southern Spain and the siege of Lisbon (1147 AD), in Portugal. The decline of the Fatimid Caliphate's naval strength, which started before the First Crusade, helped the maritime Italian states, mainly Venice, Genoa and Pisa, dominate trade in the Eastern Mediterranean, with merchants there becoming wealthy and politically influential. Further changing the mercantile situation in the eastern Mediterranean was the waning of Christian Byzantine naval power following the death of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos in 1180, whose dynasty had made notable treaties and concessions with Italian traders, permitting the use of Byzantine Christian ports. The Norman Conquest of England, in the late 11th century, allowed for peaceful trade on the North Sea. The Hanseatic League, a confederation of merchant guilds and their towns in north Germany, along the North Sea and Baltic Sea, was instrumental in the commercial development of the region. In the 12th century, the regions of Flanders, Hainault, and Brabant produced the finest quality textiles in northwest Europe, which encouraged merchants from Genoa and Venice to sail there from the Mediterranean, through the Strait of Gibraltar, and up the Atlantic coast.[32]: 316–38 Nicolòzzo Spinola made the first recorded direct voyage from Genoa to Flanders in 1277.[32]: 328

Technology: Ship design and the compass

Technological advancements that were important to the Age of Exploration were the adoption of the magnetic compass and advances in ship design.

The compass was an addition to the ancient method of navigation based on sightings of the sun and stars. It was invented during the Chinese Han dynasty and had been used for navigation in China by the 11th century. It was adopted by Arab traders in the Indian Ocean. The compass spread to Europe by the late 12th or early 13th century.[33] Use of the compass for navigation in the Indian Ocean was first mentioned in 1232.[32]: 351–2 The first mention of use of the compass in Europe was in 1180.[32]: 382 The Europeans used a "dry" compass, with a needle on a pivot. The compass card was also a European invention.[32]

The ships of the Age of Discovery post-dated the fusion of the northern European[a] and Mediterranean shipbuilding traditions. Prior to the late 13th/early 14th centuries, northern European ships were typically clinker built,[b] with a single mast setting a square sail and a centre-line rudder hung on the sternpost with pintles and gudgeons. Their counterparts in the Mediterranean were built with carvel hulls, had one or more masts (depending on size) which set lateen sails, and were steered with quarter-rudders positioned on the side of the hull.[34]: 65–66

Trade, pilgrimage and war brought ships from each tradition into the other's region, ultimately leading to the copying of features that were new to each. Over the early 14th century, square sails started to be used in the Mediterranean, with the mainmast setting square rig and the mizzen carrying a lateen sail. In the first two decades of the 15th century this arrangement was copied in northern Europe where, by the late 1430s, some ships were built with carvel hulls. The result of this merging of traditions was the full-rigged ship, a carvel hull with a sternpost-hung pintle-and-gudgeon rudder and three masts: the foremast and mainmast setting square sails and the mizzen a lateen sail. Alongside this type of vessel, the caravel was used. This type was also carvel built with a sternpost-hung rudder but could be completely lateen rigged or have some square sails.[34]: 68–72

Very few wrecks of Age of Discovery ships have been found and archaeologically investigated. More is known about Roman and Greek ships of classical antiquity than those of this period. The caravel is particularly poorly understood, despite the number of "replicas" that have been constructed.[35]: 2 However, a particular set of hull construction characteristics have been identified from wrecks of this time, referred to as Iberian Atlantic shipbuilding tradition. They are found in the Molasses Reef wreck, Highbourne Cay wreck, the Red Bay wreck and some sites in European waters.[36]: 636 [35]: 2

Early geographical knowledge and maps

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a document from 40 to 60 AD, describes a newly discovered route through the Red Sea to India, with descriptions of the markets in towns around Red Sea, Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, including along the east coast of Africa, which states "for beyond these places the unexplored ocean curves around toward the west, and running along by the regions to the south of Aethiopia and Libya and Africa, it mingles with the western sea (possible reference to the Atlantic Ocean)". European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of the Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends,[37] dating back from the conquests of Alexander the Great and successors. Another source was the Radhanite Jewish trade networks of merchants established as go-betweens between Europe and the Muslim world during the time of the Crusader states.

In 1154, the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created a description of the world and a world map, the Tabula Rogeriana, at the court of King Roger II of Sicily,[38][39] but still Africa was only partially known to either Christians, Genoese and Venetians, or the Arab seamen, and its southern extent was unknown. There were reports of great African Sahara, but the knowledge was limited for the Europeans, to the Mediterranean coast and little else, since the Arab blockade of North Africa precluded exploration inland. Knowledge about the Atlantic African coast was fragmented and derived mainly from old Greek and Roman maps based on Carthaginian knowledge, including Roman exploration of Mauritania. The Red Sea was barely known and only trade links with the Maritime republics, Venice especially, fostered the collection of accurate maritime knowledge.[40] Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders.

By 1400, a Latin translation of Ptolemy's Geographia reached Italy from Constantinople. The rediscovery of Roman geographical knowledge was a revelation,[41] both for map-making and worldview,[42] although reinforcing the idea that the Indian Ocean was landlocked.

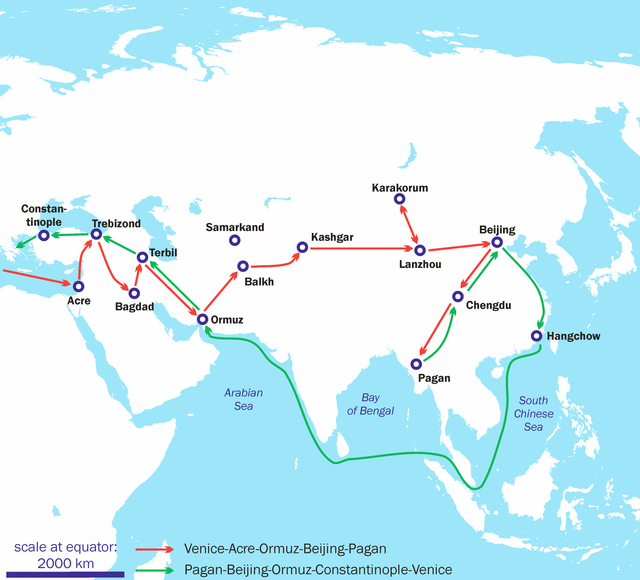

Medieval European travel (1241–1438)

A prelude to the Age of Discovery was a series of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages.[43] The Mongols had threatened Europe, but Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines from the Middle East to China.[44][45] The close Italian links to the Levant raised curiosity and commercial interest in countries which lay further east.[46][page needed] There are a few accounts of merchants from North Africa and the Mediterranean, who traded in the Indian Ocean in late medieval times (see also Indo-Mediterranean § Medieval era).[32]

Christian embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of the Levant, from which they gained a greater understanding of the world.[47][48] The first of these travellers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, dispatched by Pope Innocent IV to the Great Khan, who journeyed to Mongolia and back from 1241 to 1247.[44] Russian prince Yaroslav of Vladimir, and his sons Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, travelled to the Mongolian capital. Though having strong political implications, their journeys left no detailed accounts. Other travellers followed, like French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, who reached China through Central Asia.[49] Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295, describing being a guest at the Yuan dynasty court of Kublai Khan in Travels. It was read throughout Europe.[50]

The Muslim fleet guarding the Strait of Gibraltar was defeated by Genoa in 1291.[51] In that year, the Genoese attempted their first Atlantic exploration when merchant brothers Vadino and Ugolino Vivaldi sailed from Genoa with two galleys, but disappeared off the Moroccan coast, feeding fears of oceanic travel.[52][53] From 1325 to 1354, a Moroccan scholar from Tangier, Ibn Battuta, journeyed through North Africa, the Sahara desert, West Africa, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, having reached China. After returning, he dictated an account to a scholar he met in Granada, The Rihla ("The Journey"),[54] the unheralded source on his adventures.[55] Between 1357 and 1371 a book of supposed travels compiled by John Mandeville acquired popularity. Despite the unreliable and often fantastical nature of its accounts, it was used as a reference[56] for the East, Egypt, and the Levant in general, asserting the old belief that Jerusalem was the centre of the world. Following the period of Timurid relations with Europe, in 1439, Niccolò de' Conti published an account of his travels as a Muslim merchant to India and Southeast Asia. In 1466–1472, Russian merchant Afanasy Nikitin of Tver travelled to India, which he described in his book A Journey Beyond the Three Seas.

These overland journeys had little immediate effect. The Mongol Empire collapsed almost as quickly as it formed and soon the route to the east became more difficult and dangerous. The Black Death of the 14th century also blocked travel and trade for a time.[57]

Religion

Religion played a critical role in motivating European expansionism. In 1487, Portuguese envoys Pero da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva were sent on a covert mission to gather intelligence on a potential sea route to India and inquire about Prester John, a Nestorian patriarch and king, believed to rule over parts of the subcontinent. Covilhã was warmly received upon his arrival in Ethiopia, but forbidden from leaving.[58]

During the Middle Ages, the spread of Christianity throughout Europe fueled the desire to sermonise in lands beyond. This evangelical effort became a significant part of the military conquests of European powers, like Portugal, Spain, and France, often leading to the conversion of indigenous peoples, voluntarily or forced.[59][60]

Religious orders such as the Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians, and Jesuits partook in most missionary endeavours in the New World. By the late 16th and 17th centuries, the latter's presence increased as they sought to reassert their power and revive the Catholic culture of Europe, which had been damaged by the Reformation.[61]

Chinese missions (1405–1433)

The Chinese had wide connections through trade in Asia and been sailing to Arabia, East Africa, and Egypt since the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907). Between 1405 and 1421, the third Ming emperor Yongle sponsored long range tributary missions in the Indian Ocean under the command of admiral Zheng He.[62]

A large fleet of new junk ships was prepared for the international diplomatic expeditions. The largest of these junks—that the Chinese termed bao chuan (treasure ships)—may have measured 121 metres, and thousands of sailors were involved. The first expedition departed in 1405. At least seven well-documented expeditions were launched, each bigger and more expensive than the last. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Malay Archipelago and Thailand (then called Siam), exchanging goods along the way.[63] They presented gifts of gold, silver, porcelain and silk; in return, received such novelties as ostriches, zebras, camels, ivory and giraffes.[64][65] After the emperor's death, Zheng He led a final expedition departing from Nanking in 1431 and returning to Beijing in 1433. It is likely this last expedition reached as far as Madagascar. The travels were reported by Ma Huan, a Muslim voyager and translator who accompanied Zheng He on three of the expeditions, his account published as the Yingya Shenglan (Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores) (1433).[66]

The voyages had a significant and lasting effect on the organization of a maritime network, using and creating nodes and conduits in its wake, thereby restructuring international and cross-cultural relationships and exchanges.[67] It was especially impactful as no other polity had exerted naval dominance over all sectors of the Indian Ocean, prior to these voyages.[68] The Ming promoted alternative nodes as a strategy to establish control over the network.[69] For instance, due to Chinese involvement, ports such as Malacca (in Southeast Asia), Cochin (Malabar Coast), and Malindi (Swahili Coast) had grown as key alternatives to other established ports.[c][70] The appearance of the Ming treasure fleet generated and intensified competition among contending polities and rivals, each seeking an alliance with the Ming.[67] The expeditions developed into a maritime trade enterprise, with imperial control over local markets and court-monitored transactions, generating revenue for China and its partners. They boosted regional trade and production, caused a supply shock in Eurasia and led to price spikes in Europe in the early 15th century.[71]

The tributary relations promoted during the voyages manifested a trend toward cross-regional interconnections and early globalization in Asia and Africa.[72] Diplomatic relations were built on mutually beneficial maritime trade and China's strong naval presence in foreign waters, with Chinese naval superiority being a key factor in these interactions.[73] The voyages brought about the Western Ocean's regional integration and increase in international circulation of people, ideas, and goods. It provided a platform for cosmopolitan discourses, which took place in locations such as the ships of the Ming treasure fleet, the Ming capitals of Nanjing as well as Beijing, and the banquet receptions organized by the Ming court for foreign representatives.[67] Diverse groups of people from maritime countries congregated, interacted, and traveled together as the treasure fleet sailed from and to China.[67] For the first time, the maritime region from China to Africa was under the dominance of a single imperial power and allowed for the creation of a cosmopolitan space.[74]

These long-distance journeys were not followed up, as the Ming dynasty retreated in the haijin, a policy of isolationism, having limited maritime trade. Travels were halted abruptly after the emperor's death, as the Chinese lost interest in what they termed barbarian lands, turning inward,[75] and successor emperors felt the expeditions were harmful to the Chinese state; Hongxi Emperor ended further expeditions and Xuande Emperor suppressed much of the information about Zheng He's voyages.

Remove ads

Atlantic Ocean (1419–1507)

Summarize

Perspective

From the 8th until the 15th century, the Republic of Venice and neighboring maritime republics held the monopoly of European trade with the Middle East. The silk and spice trade, involving spices, incense, herbs, drugs and opium, made these Mediterranean city-states phenomenally rich. Spices were among the most expensive and demanded products of the Middle Ages, as they were used in medieval medicine,[76] religious rituals, cosmetics, perfumery, food additives and preservatives.[77] They were imported from Asia and Africa.

Muslim traders dominated maritime routes throughout the Indian Ocean, tapping source regions in the Far East and shipping for trading emporiums in India, mainly Kozhikode, westward to Ormus in the Persian Gulf and Jeddah in the Red Sea. From there, overland routes led to the Mediterranean. Venetian merchants distributed the goods through Europe until the rise of the Ottoman Empire, which led to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, barring Europeans from important combined-land-sea routes. The Venetians and other maritime republics maintained more limited access to Asian goods, via south-eastern Mediterranean trade, in such ports as Antioch, Acre, and Alexandria.

Forced to reduce activity in the Black Sea, and at war with Venice, the Genoese had turned to North African trade of wheat, olive oil and a search for silver and gold. Europeans had a constant deficit in silver and gold,[78] as it only went out, spent on eastern trade now cut off. Several European mines were exhausted,[79] The lack of bullion led to the development of a complex banking system to manage the risks in trade (the first state bank, Banco di San Giorgio, was founded in 1407 at Genoa). Sailing into the ports of Bruges and England, Genoese communities were then established in Portugal,[80] who profited from their enterprise and financial expertise.

European sailing had been primarily close to land cabotage, guided by portolan charts. These charts specified proven ocean routes guided by coastal landmarks: sailors departed from a known point, followed a compass heading, and tried to identify their location by its landmarks.[81] For the first oceanic exploration Europeans used the compass, and advances in cartography and astronomy. Arab navigational tools like the astrolabe and quadrant were used for celestial navigation.

The Muslim lands in Asia were more economically developed, had better infrastructure, despite Europe's economic changes brought by the Black Death, allowing for more freedoms.[82] The Islamic gunpowder empires concealed knowledge from European Christian traders about where lucrative locations such as Indonesia were.[82]

Portuguese exploration

In 1317, King Denis of Portugal made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha, appointing him first admiral of the Portuguese Navy, to defend the country against Muslim pirate raids.[83] Outbreaks of bubonic plague led to depopulation in the second half of the 14th century: only the sea offered alternatives, with most population settling in fishing and trading coastal areas.[84] Between 1325 and 1357, Afonso IV of Portugal encouraged maritime commerce and ordered the first explorations.[85] The Canary Islands, already known to the Genoese, were claimed as officially discovered under the patronage of the Portuguese, but in 1344 Castile disputed them.[86][87]

To ensure their trade monopoly, Europeans, beginning with the Portuguese, attempted to install a Mediterranean system of trade which used military intimidation, to divert trade through ports they controlled; there it could be taxed.[88] In 1415, Ceuta, in North Africa, was conquered by the Portuguese aiming to control navigation of the African coast. Young prince Henry the Navigator became aware of profit possibilities in the trans-Saharan trade routes. For centuries slave and gold trade routes linking West Africa with the Mediterranean passed over the Western Sahara Desert, controlled by the Moors. Henry wished to know how far Muslim territories in Africa extended, hoping to bypass them and trade directly with West Africa by sea, find allies in legendary Christian lands[89] like the supposed long-lost kingdom of Prester John[90] and probe whether it was possible to reach the Indies by sea, the source of the lucrative spice trade. He invested in sponsoring voyages down the coast of Mauritania, gathering merchants, shipowners and stakeholders interested in new sea lanes. Soon the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1419) and the Azores (1427) were reached. The expedition leader who established settlements on Madeira, was explorer João Gonçalves Zarco.[91]

Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Non (Cape Chaunar) on the African coast, and whether it was possible to return once crossed.[92] Nautical myths warned of monsters or an edge of the world, but Henry's navigation challenged such beliefs: starting in 1421, systematic sailing overcame it, reaching the difficult Cape Bojador that in 1434 one of Henry's captains, Gil Eanes, finally passed.

From 1440, caravels were extensively used for the exploration of the coast of Africa. This was an Iberian ship type, used for fishing, commerce and military purposes. It had a sternpost-mounted rudder, a shallow draft helpful in exploring coastlines, a good sailing performance, with a windward ability.[d] The lateen rig was less useful when sailing downwind – which explains Christopher Columbus (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo) re-rigging the Niña with square rig.[94]: 96

For celestial navigation the Portuguese used the ephemerides, which experienced a remarkable diffusion in the 15th century. These were astronomical charts plotting the location of the stars. Published in 1496 by Jewish astronomer and mathematician Abraham Zacuto, the Almanac Perpetuum included some of these tables for the movements of stars.[95] These revolutionized navigation, allowing the calculation of latitude. Exact longitude remained elusive from mariners for centuries.[96][97] Using the caravel, systematic exploration continued southerly, advancing one degree a year.[98] Senegal and Cape Verde Peninsula were reached in 1445 and in 1446, Álvaro Fernandes pushed on almost as far as present-day Sierra Leone.

In 1453, the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans was a perceived blow to Christendom and established business links with the East. In 1455, Pope Nicholas V issued the bull Romanus Pontifex reinforcing the Dum Diversas (1452), granting all lands and seas discovered beyond Cape Bojador to King Afonso V of Portugal and successors, as well as cutting off trade to and permitting increased war against Muslims and pagans, initiating a mare clausum policy in the Atlantic, declaring it close to other states.[99] The king, who had been inquiring of Genoese experts about a seaway to India, commissioned the Fra Mauro world map, which arrived in Lisbon in 1459.[100] In 1456, Diogo Gomes reached the Cape Verde archipelago. In the next decade captains at the service of Prince Henry, discovered the remaining islands which were occupied during the 15th century. The Gulf of Guinea was reached in the 1460s.

After Prince Henry

In 1460, Pedro de Sintra reached Sierra Leone. Prince Henry died in November after which, given the meagre revenues, exploration was granted to Lisbon merchant Fernão Gomes in 1469, who in exchange for the monopoly of trade in the Gulf of Guinea had to explore 100 miles (161 kilometres) each year for five years.[101] With his sponsorship, explorers João de Santarém, Pedro Escobar, Lopo Gonçalves, Fernão do Pó, and Pedro de Sintra made it beyond those goals. They reached the Southern Hemisphere and islands of the Gulf of Guinea, including São Tomé and Príncipe and Elmina in 1471. There, in what came to be called the "Gold Coast", in today's Ghana, a thriving alluvial gold trade was found among the natives, Arab and Berber traders.

In 1478, during the War of the Castilian Succession, near the coast at Elmina a large battle was fought between a Castilian armada of 35 caravels, and a Portuguese fleet for the hegemony of the Guinea trade. The war ended with a Portuguese victory, followed by official recognition by the Catholic Monarchs of Portuguese sovereignty over most of the disputed West African territories embodied in the Treaty of Alcáçovas, 1479.

In 1481, João II decided to build São Jorge da Mina factory. In 1482 the Congo River was explored by Diogo Cão,[102] who in 1486 continued to Cape Cross (modern Namibia).

The next crucial breakthrough was in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of Africa, which he named Cabo das Tormentas, "Cape of Storms", then sailing east as far as the mouth of the Great Fish River, proving the Indian Ocean was accessible from the Atlantic. Pero da Covilhã, sent out travelling secretly overland, had reached Ethiopia having collected important information about the Red Sea and Quenia coast, suggesting a sea route to the Indies would soon be forthcoming.[103] Soon the cape was renamed by King John II of Portugal the Cape of Good Hope, because of the optimism engendered by the possibility of a sea route to India, proving false the view that had existed since Ptolemy that the Indian Ocean was land-locked.

Based on later stories of the phantom island known as Bacalao and the carvings on Dighton Rock some have speculated that Portuguese explorer João Vaz Corte-Real discovered Newfoundland in 1473, but the sources are considered unreliable.[104]

Spanish exploration: Columbus's landfall in the Americas

Portugal's Iberian rival, Castile, had begun to establish its rule over the Canary Islands in 1402, but became distracted by internal Iberian politics and the repelling of Islamic invasion attempts through most of the 15th century. Following the unification of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, an emerging modern Spain became committed to the search for new trade routes overseas. The Crown of Aragon had been an important maritime power, controlling territories in eastern Spain, southwestern France, major islands like Sicily, Malta, and the Kingdom of Naples and Sardinia, with mainland possessions as far as Greece. In 1492 the joint rulers conquered the Moorish kingdom of Granada, which had been providing Castile with African goods through tribute, and decided to fund Christopher Columbus's expedition in the hope of bypassing Portugal's monopoly on west African sea routes, to reach "the Indies" (east and south Asia) by travelling west.[105] In 1485 and 1488, Columbus had presented the project to king John II of Portugal, who rejected it.

On 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera. Land was sighted on 12 October, and Columbus called the island San Salvador (Guanahani now in The Bahamas), in what he thought to be the East Indies. Columbus explored the north coast of Cuba and Hispaniola, by 5 December. He was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some men behind.

Columbus left 39 and founded the settlement of La Navidad in what is now Haiti.[106] Before returning to Spain, he kidnapped 10-25 natives. Only 7-8 of the 'Indians' arrived alive, but they made an impression on Seville.[107] On 15 March 1493 he arrived in Barcelona, where he reported to Isabella and Ferdinand. Word of his discovery of new lands spread throughout Europe.[108]

Columbus and other Spanish explorers were initially disappointed with their discoveries—unlike Africa or Asia, the Caribbean islanders had little to trade. The islands thus became the focus of colonization efforts. It was not until the continent was explored that Spain found the wealth it had sought.

Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

Shortly after Columbus's return from what would be called the "West Indies", a division of influence became necessary to avoid conflict between the Spanish and Portuguese.[109] On 4 May 1493, two months after Columbus's arrival, the Catholic Monarchs received a bull (Inter caetera) from Pope Alexander VI stating all lands west and south of a pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west and south of the Azores or the Cape Verde Islands should belong to Castile and, later, all mainlands and islands then belonging to India. It did not mention Portugal, which could not claim newly discovered lands east of the line.

King John II of Portugal was displeased with the arrangement, feeling it gave him too little land—preventing him from reaching India, his goal. He negotiated directly with Ferdinand and Isabella to move the line west, allowing him to claim newly discovered lands east of it.[110] In 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the world between Portugal and Spain. Portugal gained control over Africa, Asia, and eastern South America (Brazil), encompassing everything outside Europe east of a line drawn 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands. The Spanish received everything west of this line, including the islands discovered by Columbus on his first voyage. The dividing line, situated about halfway between Portuguese Cape Verde and Spanish discoveries in the Caribbean, split the known world of Atlantic islands evenly.

In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral, initially considering the Brazilian coast as a large island, claimed it for Portugal east of the dividing line. This claim was acknowledged by the Spanish. Cabral, heading towards India, followed a corridor in the Atlantic negotiated by the treaty for favorable winds. Later the Spanish territory would prove to include huge areas of the continental mainland of North and South America, though Portuguese-controlled Brazil would expand across the line, and settlements by other European powers ignored the treaty.

The Americas: The New World

Little of the divided area had actually been seen by Europeans, as it was only divided by a geographical definition rather than control on the ground. The desire to compete with the Ottoman Empire and Columbus's first voyage spurred further maritime exploration and, from 1497, other explorers headed west.

North America

That year John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto), also a commissioned Italian, got letters patent from King Henry VII of England. Sailing from Bristol Cabot crossed the Atlantic from a northerly latitude hoping the voyage to the "West Indies" would be shorter[111] and made landfall in North America, possibly Newfoundland.

In 1499 João Fernandes Lavrador was licensed by the King of Portugal and together with Pero de Barcelos they first sighted Labrador, which was granted and named after him.[112] Between 1499 and 1502 the brothers Gaspar and Miguel Corte Real explored and named the coasts of Greenland and Newfoundland.[113] Both explorations are noted in the 1502 Cantino planisphere.

The "True Indies" and Brazil

In 1497, newly crowned King Manuel I of Portugal sent an exploratory fleet eastwards, fulfilling his predecessor's project of finding a route to the Indies. In July 1499, news spread that the Portuguese had reached the "true Indies", as a letter was dispatched by the Portuguese king to the Spanish Monarchs.[114]

The third expedition by Columbus in 1498 was the beginning of the first successful Spanish colonization in the West Indies, on the island of Hispaniola. Despite growing doubts, Columbus refused to accept he had not reached the Indies. He discovered the mouth of the Orinoco River on the north coast of South America and thought the huge quantity of fresh water coming from it could only be from a continental land mass, which he was certain was Asia.

As shipping between Seville and the West Indies grew, knowledge of the Caribbean islands, Central America and the northern coast of South America increased. One of these Spanish fleets, that of Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci in 1499–1500 reached land at the coast of what is now Guyana, where the two seem to have separated in opposite directions. Vespucci sailed southward, discovering the mouth of the Amazon River in July 1499,[115][116] and reaching 6°S, in present-day north east Brazil, before turning around.

Vicente Yáñez Pinzon was blown off course and reached what is now the northeast coast of Brazil on 26 January 1500, exploring as far south as the present-day state of Pernambuco. His fleet was the first to fully enter the Amazon River estuary, which he named Saint Mary's River of the Freshwater Sea.[117] The land was too far east for the Castilians to claim under the Treaty of Tordesillas, but the discovery created Castilian interest, with a second voyage by Pinzon in 1508 (the Pinzón–Solís voyage) and a voyage in 1515–16 by a navigator of the 1508 expedition, Juan Díaz de Solís. The 1515–16 expedition was spurred on by reports of Portuguese exploration of the region. It ended when de Solís and some of his crew disappeared when exploring the River Plata in a boat, but what they found reignited Spanish interest, and colonization began in 1531.

In April 1500, the second Portuguese India Armada, headed by Pedro Álvares Cabral, with a crew of expert captains, encountered the Brazilian coast as it swung westward in the Atlantic while performing a large volta do mar to avoid becalming in the Gulf of Guinea. On 21 April, a mountain was seen and named Monte Pascoal, and on 22 April Cabral landed. On 25 April, the entire fleet sailed into the harbour they named Porto Seguro. Cabral perceived that the new land lay east of the line of Tordesillas, and sent an envoy to Portugal with the discovery in letters, including the letter of Pero Vaz de Caminha. Believing the land to be an island, he named it Ilha de Vera Cruz.[118] Some historians have suggested the Portuguese may have encountered the South American bulge earlier while sailing the "volta do mar", hence the insistence of John II in moving the line west of Tordesillas in 1494—so his landing in Brazil may not have been accidental; although John's motivation may have simply been to claim new lands in the Atlantic more easily.[119] From the east coast, the fleet then turned eastward towards the southern tip of Africa and India. Cabral was the first captain to touch four continents, leading the first expedition that connected and united Europe, Africa, the New World, and Asia.[120][121]

At the invitation of King Manuel I of Portugal, Amerigo Vespucci[122] participated as an observer in the exploratory voyages to the east coast of South America. The expeditions became widely known in Europe after two accounts attributed to him, published between 1502 and 1504, suggested the newly discovered lands were not the Indies but a "New World",[123] the Mundus novus; this is also the Latin title of a contemporary document based on Vespucci letters to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, which had become popular in Europe.[124] It was understood that Columbus had not reached Asia but found a new continent, the Americas. The Americas were named in 1507 by cartographers Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann, after Amerigo Vespucci.

From 1501 to 1502, one of these Portuguese expeditions, led by Gonçalo Coelho, sailed south along the coast of South America to the bay of present-day Rio de Janeiro. Vespucci's account states that the expedition reached the latitude "South Pole elevation 52° S", in the "cold" latitudes of what is now southern Patagonia, before turning back. Vespucci wrote that they headed toward the southwest and south, following "a long, unbending coastline", apparently coincident with the southern South American coast. This seems controversial, since he changed part of his description in the subsequent letter, stating a shift, from about 32° S (Southern Brazil) to the south-southeast, to open sea, maintaining that they reached 50°/52° S.[125][126]

In 1503, Binot Paulmier de Gonneville, challenging the Portuguese policy of mare clausum, led one of the earliest French Normand and Breton expeditions to Brazil. He intended to sail to the East Indies, but near the Cape of Good Hope, his ship was diverted to the west by a storm, and landed in the present-day state of Santa Catarina (southern Brazil), on 5 January 1504.

From 1511 to 1512, Portuguese captains João de Lisboa and Estevão de Fróis reached the River Plata estuary in present-day Uruguay and Argentina, and went as far south as the present-day Gulf of San Matias at 42°S.[127][128] The expedition reached a cape extending north to south which they called Cape of "Santa Maria" (Punta del Este); and after 40°S they found a "Cape" or "a point or place extending into the sea", and a "Gulf". After they had navigated for nearly 300 km (186 mi) to round the cape, they again sighted the continent on the other side and steered towards the northwest, but a storm prevented them from making headway. Driven away by the Tramontane or north wind, they retraced their course.[129] Christopher de Haro, a Fleming of Sephardic origin, who would serve the Spanish Crown after 1516, believed the navigators had discovered a southern strait to west and Asia.

In 1519, an expedition sent by the Spanish Crown to find a way to Asia was led by the experienced Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan. The fleet explored the rivers and bays as it charted the South American coast, until it found a way to the Pacific Ocean through the Strait of Magellan.

From 1524 to 1525, Aleixo Garcia, a Portuguese conquistador, led a private expedition of shipwrecked Castilian and Portuguese adventurers, who recruited about 2,000 Guaraní Indians. They explored the territories of present-day southern Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia, using the native trail network, the Peabiru. They were the first Europeans to cross the Chaco and reach the outer territories of the Inca Empire on the hills of the Andes.[130]

Remove ads

Indian Ocean (1497–1513)

Summarize

Perspective

Vasco da Gama's route to India

Protected from direct Spanish competition by the Treaty of Tordesillas, Portuguese eastward exploration and colonization continued apace. Twice, in 1485 and 1488, Portugal officially rejected Genoese Christopher Columbus's idea of reaching India by sailing westwards. King John II of Portugal's experts rejected it, for they held the opinion that Columbus's estimation of a travel distance of 2,400 miles (3,860 km) was low,[131] and in part because Bartolomeu Dias departed in 1487 trying the rounding of the southern tip of Africa. They believed that sailing east would require a far shorter journey. Dias's return from the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, and Pero da Covilhã's travel to Ethiopia overland indicated that the richness of the Indian Ocean was accessible from the Atlantic. A long-overdue expedition was prepared.

In July 1497, a small exploratory fleet of four ships and about 170 men left Lisbon under the command of Vasco da Gama. By December the fleet passed the Great Fish River—where Dias had turned back—and sailed into waters unknown to the Europeans. Sailing into the Indian Ocean, da Gama entered a maritime region that had three different and well-developed trade circuits. The one da Gama encountered connected Mogadishu on the east coast of Africa; Aden, at the tip of the Arabian peninsula; the Persian port of Hormuz; Cambay, in northwestern India; and Calicut, in southwestern India.[132] On 20 May 1498, they arrived at Calicut. The efforts of Vasco da Gama to get favorable trading conditions were hampered by the low value of their goods, compared with the valuable goods traded there.[133][page needed] Two years and two days after departure, Gama and a survivor crew of 55 men returned in glory to Portugal as the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India. Da Gama's voyage is romanticized in the Os Lusíadas, an epic poem by fellow discovery-era traveler Luís de Camões. The poem is widely regarded as Portugal's greatest literary achievement.[134][135]

In 1500, a second, larger fleet of thirteen ships and about 1500 men were sent to India. Under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral, they made the first landfall on the Brazilian coast, giving Portugal its claim. Later, in the Indian Ocean, one of Cabral's ships reached Madagascar (1501), which was partly explored by Tristão da Cunha in 1507; Mauritius was discovered in 1507, Socotra occupied in 1506. In the same year Lourenço de Almeida landed in Sri Lanka, the eastern island named "Taprobane" in remote accounts of Alexander the Great's and 4th-century BC Greek geographer Megasthenes. On the Asiatic mainland, the first factories (trading-posts) were established at Kochi and Calicut (1501) and then Goa (1510).

The "Spice Islands" and China

The Portuguese continued sailing eastward from India, entering a second existing circuit of the Indian Ocean trade, from Calicut and Quillon in India, to southeast Asia, including Malacca, and Palembang.[132] In 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca for Portugal, then the center of Asian trade. East of Malacca, Albuquerque sent several diplomatic missions: Duarte Fernandes as the first European envoy to the Kingdom of Siam (modern Thailand).

Learning the location of the so-called "spice islands", heretofore a secret from the Europeans, were the Maluku Islands, mainly the Banda, then the world's only source of nutmeg and cloves. Reaching these was the main purpose for the Portuguese voyages in the Indian Ocean. Albuquerque sent an expedition led by António de Abreu to Banda (via Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands), where they were the first Europeans to arrive in early 1512, after taking a route through which they also reached first the islands of Buru, Ambon and Seram.[136][137] From Banda Abreu returned to Malacca, while his vice-captain Francisco Serrão, after a separation forced by a shipwreck and heading north, reached once again Ambon and sank off Ternate, where he obtained a license to build a Portuguese fortress-factory: the Fort of São João Baptista de Ternate, which founded the Portuguese presence in the Malay Archipelago.

In May 1513 Jorge Álvares, one of the Portuguese envoys, reached China. Although he was the first to land on Lintin Island in the Pearl River Delta, it was Rafael Perestrello—a cousin of the famed Christopher Columbus—who became the first European explorer to land on the southern coast of mainland China and trade in Guangzhou in 1516, commanding a Portuguese vessel with crew from a Malaccan junk that had sailed from Malacca.[138][139] Fernão Pires de Andrade visited Canton in 1517 and opened up trade with China. The Portuguese were defeated by the Chinese in 1521 at the Battle of Tunmen and in 1522 at the Battle of Xicaowan, during which the Chinese captured Portuguese breech-loading swivel guns and reverse engineered the technology, calling them "Folangji" 佛郎機 (Frankish) guns, since the Portuguese were called "Folangji" by the Chinese. After a few decades, hostilities between the Portuguese and Chinese ceased and in 1557 the Chinese allowed the Portuguese to occupy Macau.

To enforce a trade monopoly, Muscat and Hormuz in the Persian Gulf were seized by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1507 and in 1515, respectively. He also entered into diplomatic relations with Persia. In 1513, while trying to conquer Aden, an expedition led by Albuquerque cruised the Red Sea inside the Bab al-Mandab and sheltered at Kamaran island. In 1521, a force under António Correia conquered Bahrain, ushering in a period of almost eighty years of Portuguese rule of the Gulf archipelago.[140] In the Red Sea, Massawa was the most northerly point frequented by the Portuguese until 1541, when a fleet under Estevão da Gama penetrated as far as Suez.

Remove ads

Pacific Ocean (1513–1529)

Summarize

Perspective

Balboa's expedition to the Pacific Ocean

In 1513, about 40 miles (64 kilometres) south of Acandí, in present-day Colombia, Spanish Vasco Núñez de Balboa heard unexpected news of an "other sea" rich in gold, which he received with great interest.[141] With few resources and using information given by caciques, he journeyed across the Isthmus of Panama with 190 Spaniards, a few native guides, and a pack of dogs.

Balboa, using a brigantine and ten native canoe, explored the coast, facing battles and dense jungles. On September 25, after crossing the Chucunaque River mountains, he became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean from the New World. The expedition briefly navigated the Pacific, naming the bay San Miguel and the sea Mar del Sur (South Sea). Seeking gold, Balboa traversed cacique lands to the islands, naming the largest Isla Rica (now Isla del Rey) and the group Archipiélago de las Perlas, names still in use today.[citation needed]

Subsequent developments to the east

From 1515 to 1516, the Spanish fleet led by Juan Díaz de Solís sailed down the east coast of South America as far as Río de la Plata, which Solís named shortly before he died while trying to find a passage to the "South Sea".

First circumnavigation

By 1516, several Portuguese navigators conflicting with King Manuel I of Portugal gathered in Seville to serve the newly crowned Charles I of Spain. Among them were explorers Diogo and Duarte Barbosa, Estêvão Gomes, João Serrão and Ferdinand Magellan, cartographers Jorge Reinel and Diogo Ribeiro, cosmographers Francisco and Ruy Faleiro and the Flemish merchant Christopher de Haro. Ferdinand Magellan had sailed in India for Portugal up to 1513, when the Maluku Islands were reached, and had kept contact with Francisco Serrão who was living there.[142][143] Magellan developed the theory that the Maluku Islands were in the Tordesillas Spanish area, based on studies by Faleiro brothers.

Aware of the efforts of the Spanish to find a route to India by sailing west, Magellan presented his plan to Charles I of Spain. The king and Christopher de Haro financed Magellan's expedition. A fleet was put together, and Spanish navigators such as Juan Sebastián Elcano joined the enterprise. On August 10, 1519, they departed from Seville with a fleet of five ships—the caravel flagship Trinidad under Magellan's command, and carracks San Antonio, Concepcion, Santiago and Victoria. They contained a crew of about 237 European men from several regions, with the goal of reaching the Maluku Islands by travelling west, trying to reclaim it under Spain's economic and political sphere.[144]

The fleet sailed south, avoiding Portuguese Brazil, and became the first to reach Tierra del Fuego. Starting on October 21, they navigated the 373-mile (600 km) Strait of Magellan, entering the Pacific on November 28, which Magellan named Mar Pacífico for its calm waters.[145] After crossing the Pacific, Magellan was killed in the battle of Mactan in the Philippines. Juan Sebastián Elcano completed the voyage, reaching the Spice Islands in 1521. On September 6, 1522, the Victoria returned to Spain, completing the first circumnavigation of the globe. Of the original crew, only 18 men completed the circumnavigation; 17 returned later, including twelve captured by the Portuguese and five survivors of the Trinidad. Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian scholar, kept a detailed journal that is a key source of information about the voyage.[citation needed]

This round-the-world voyage gave Spain valuable knowledge of the world and its oceans which later helped in the exploration and settlement of the Philippines. Although this was not a realistic alternative to the Portuguese route around Africa[146] (the Strait of Magellan was too far south, and the Pacific Ocean too vast to cover in a single trip from Spain) successive Spanish expeditions used this information to explore the Pacific Ocean and discovered routes that opened up trade between Acapulco, New Spain (present-day Mexico) and Manila in the Philippines.[147]

Westward and eastward exploration meet

Soon after Magellan's expedition, the Portuguese rushed to seize the surviving crew and built a fort in Ternate.[148] In 1525, Charles I of Spain sent another expedition westward to colonize the Maluku Islands, claiming that they were in his zone of the Treaty of Tordesillas. The fleet of seven ships and 450 men was led by García Jofre de Loaísa and included the most notable Spanish navigators: Juan Sebastián Elcano and Loaísa, who died then, and the young Andrés de Urdaneta.

Near the Strait of Magellan one of the ships was pushed south by a storm, reaching 56° S, where they thought seeing "earth's end": so Cape Horn was crossed for the first time. The expedition reached the islands with great difficulty, docking at Tidore.[148] The conflict with the Portuguese established in nearby Ternate was inevitable, starting nearly a decade of skirmishes.[150][151]

As there was not a set eastern limit to the Tordesillas line, both kingdoms organized meetings to resolve the issue. From 1524 to 1529, Portuguese and Spanish experts met at Badajoz-Elvas trying to find the exact location of the antimeridian of Tordesillas, which would divide the world into two equal hemispheres. Each crown appointed three astronomers and cartographers, three pilots, and three mathematicians. Lopo Homem, Portuguese cartographer and cosmographer was on the board, along with cartographer Diogo Ribeiro of the Spanish delegation. The board met several times without reaching an agreement: the knowledge at that time was insufficient for an accurate calculation of longitude, and each group gave the islands to its sovereign. The issue was settled only in 1529, after a long negotiation, with the signing of Treaty of Zaragoza, which allocated the Maluku Islands to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.[152]

From 1525 to 1528, Portugal sent several expeditions around the Maluku Islands. Gomes de Sequeira and Diogo da Rocha were sent north by the governor of Ternate Jorge de Menezes, being the first Europeans to reach the Caroline Islands, which they named Islands of Gomes de Sequeira.[153] In 1526, Jorge de Meneses docked on Biak and Waigeo islands, Papua New Guinea. Based on these explorations stands the theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia, one among several competing theories about the early discovery of Australia, supported by Australian historian Kenneth McIntyre, stating it was discovered by Cristóvão de Mendonça and Gomes de Sequeira.

In 1527, Hernán Cortés fitted out a fleet to find new lands in the "South Sea" (Pacific Ocean), asking his cousin Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón to take charge. On 31 October 1527, Saavedra sailed from New Spain, crossing the Pacific and touring the north of New Guinea, then named Isla de Oro. In October 1528, one of the vessels reached the Maluku Islands. In his attempt to return to New Spain he was diverted by the northeast trade winds, which threw him back, so he tried sailing back down, to the south. He returned to New Guinea and sailed northeast, where he sighted the Marshall Islands and the Admiralty Islands, but again was surprised by the winds, which brought him a third time to the Moluccas. This westbound return route was hard to find but was eventually discovered by Andrés de Urdaneta in 1565.[154]

Remove ads

Inland Spanish expeditions (1519–1532)

Summarize

Perspective

Rumors of undiscovered islands northwest of Hispaniola reached Spain by 1511, ushering King Ferdinand's interest in forestalling further exploration. While the Portuguese were making huge gains in the Indian Ocean, the Spanish invested in exploring inland in search of gold and other valuable resources. The members of these expeditions, the conquistadors, were not soldiers in an army, but more like soldiers of fortune; they came from a variety of backgrounds including artisans, merchants, clergy, lawyers, lesser nobility and a few freed slaves. They usually supplied their own equipment or were extended credit to purchase it in exchange for a share in profits. They usually had no professional military training, but a number of them had previous experience on other expeditions.[155]

In the Americas, the Spanish encountered large indigenous empires and formed alliances with indigenous people through small expeditions. After establishing Spanish sovereignty and discovering wealth, the crown focused on implementing Spanish state and church institutions. A key element was the 'spiritual conquest' through Christian evangelization. The initial economy relied on a tribute and forced labor under the encomienda system. The discovery of vast silver deposits transformed both the colonial economies of Mexico and Peru and Spain's economy. With global trade networks and valuable American crops, Spain's economy strengthened, enhancing its status as a world power.[citation needed]

During this time, pandemics of European diseases such as smallpox decimated the indigenous populations.[156]

In 1512, to reward Juan Ponce de León for exploring Puerto Rico in 1508, King Ferdinand urged him to seek these new lands. He would become governor of discovered lands but was to finance himself all exploration.[157] With three ships and about 200 men, Léon set out from Puerto Rico in March 1513. In April they sighted land and named it La Florida—because it was Easter (Florida) season—believing it was an island, becoming credited as the first European to land in the continent. The arrival location has been disputed between St. Augustine,[158] Ponce de León Inlet and Melbourne Beach. They headed south for further exploration and on April 8 encountered a current so strong that it pushed them backward: this was the first encounter with the Gulf Stream that would soon become the primary route for eastbound ships leaving the Spanish Indies bound for Europe.[159] They explored down the coast reaching Biscayne Bay, Dry Tortugas and then sailing southwest in an attempt to circle Cuba to return, reaching Grand Bahama on July.

Cortés' Mexico and the Aztec Empire

In 1517, Cuba's governor Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar commissioned a fleet under the command of Hernández de Córdoba to explore the Yucatán peninsula. They reached the coast where Mayans invited them to land. They were attacked at night and only a remnant of the crew returned. Velázquez then commissioned another expedition led by his nephew Juan de Grijalva, who sailed south along the coast to Tabasco, part of the Aztec empire.

In 1518, Velázquez gave the mayor of the capital of Cuba, Hernán Cortés, the command of an expedition to secure the interior of Mexico but, due to an old gripe between them, revoked the charter. In February 1519, Cortés went ahead anyway, in an act of open mutiny. With about 11 ships, 500 men, 13 horses and a small number of cannons he landed in Yucatán, in Mayan territory,[160] claiming the land for the Spanish crown. From Trinidad he proceeded to Tabasco and won a battle against the natives. Among the vanquished was Marina (La Malinche), his future mistress, who knew both (Aztec) Nahuatl language and Maya, becoming a valuable interpreter and counsellor. Cortés learned about the wealthy Aztec Empire through La Malinche,

In July, his men took over Veracruz and he placed himself under direct orders of new king Charles I of Spain.[160] There Cortés asked for a meeting with Aztec Emperor Montezuma II, who repeatedly refused. They headed to Tenochtitlan and on the way made alliances with several tribes. In October, accompanied by about 3,000 Tlaxcaltec they marched to Cholula, the second largest city in central Mexico. Either to instill fear upon the Aztecs waiting for him or (as he later claimed) wishing to make an example when he feared native treachery, they massacred thousands of unarmed members of the nobility gathered at the central plaza and partially burned the city.

On November 8, Cortés and his large army were welcomed by Moctezuma II in Tenochtitlan, who hoped to learn about them to eventually defeat them.[160] Moctezuma gave lavish gifts, which led Cortés to plunder the city. Cortés claimed the Aztecs saw him as an emissary or incarnation of the god Quetzalcoatl, though this is contested by few historians.[161] Upon learning that his men had been attacked on the coast, Cortés took Moctezuma hostage in his palace, demanding tribute for King Charles.

Meanwhile, Velasquez sent another expedition, led by Pánfilo de Narváez, to oppose Cortès, arriving in Mexico in April 1520 with 1,100 men.[160] Cortés left 200 men in Tenochtitlan and took the rest to confront Narvaez, whom he overcame, convincing his men to join him. In Tenochtitlán one of Cortés's lieutenants committed a massacre in the Great Temple, triggering local rebellion. Cortés speedily returned, attempting the support of Moctezuma but the Aztec emperor was killed, possibly stoned by his subjects.[162] The Spanish fled for the Tlaxcaltec during the Noche Triste, where they managed a narrow escape while their back guard was massacred. Much of the treasure looted was lost during this panicked escape.[160] After a battle in Otumba they reached Tlaxcala, having lost 870 men.[160] Having prevailed with the assistance of allies and reinforcements from Cuba, Cortés besieged Tenochtitlán and captured its ruler Cuauhtémoc in August 1521. As the Aztec Empire ended he claimed the city for Spain, renaming it Mexico City.

Pizarro's Peru and the Inca Empire

A first attempt to explore western South America was undertaken in 1522 by Pascual de Andagoya. Native South Americans told him about a gold-rich territory on a river called Pirú. Having reached San Juan River (Colombia), Andagoya fell ill and returned to Panama, where he spread the news about "Pirú" as the legendary El Dorado. These, along with the accounts of the success of Hernán Cortés, caught the attention of Pizarro.

Francisco Pizarro had accompanied Balboa in the crossing of the Isthmus of Panama. In 1524 he formed a partnership with priest Hernando de Luque and soldier Diego de Almagro to explore the south, agreeing to divide the profits. They dubbed the enterprise the "Empresa del Levante": Pizarro would command, Almagro would provide military and food supplies, and Luque would be in charge of finances and additional provisions.

On 13 September 1524, the first of three expeditions set out to conquer Peru with 80 men and 40 horses. The venture failed, halting in Colombia due to bad weather, hunger, and conflicts with locals; Almagro lost an eye. Their route was marked by Puerto Deseado (desired port), Puerto del Hambre (port of hunger), and Puerto quemado (burned port). Two years later, a second expedition began with reluctant permission from the Governor of Panama. In August 1526, they departed with two ships, 160 men, and horses. Upon reaching the San Juan River, Pizarro explored swampy coasts, while Almagro sought reinforcements. Pizarro's pilot, sailing south and crossing the equator, captured a raft from Tumbes. To his surprise, the raft carried coveted textiles, ceramics, gold, silver, and emeralds, becoming the expedition's main focus. Almagro later joined with reinforcements, and despite challenging conditions, they reached Atacames, where a sizable native population under Inca rule was observed, though they did not land.

Pizarro, safe near the coast, sent Almagro and Luque for reinforcements with proof if the rumoured gold. The new governor rejected a third expedition, ordering everyone back to Panama. Almagro and Luque seized the chance to rejoin Pizarro. At Isla de Gallo, Pizarro drew a line, presenting the choice between Peru's riches and Panama's poverty. Thirteen men, The Famous Thirteen, stayed and headed to La Isla Gorgona, staying seven months until provisions arrived.

They sailed south and by April 1528, reached northwestern Peru's Tumbes Region, warmly received by the Tumpis. Pizarro's men reported incredible riches, llama sightings, and the natives named them "Children of the Sun" for their fair complexion and brilliant armour. They decided to return to Panama to prepare a final expedition, sailing south through named territories like Cabo Blanco, port of Payta, Sechura, Punta de Aguja, Santa Cruz, and Trujillo, reaching the ninth degree south.

In the spring of 1528, Pizarro sailed for Spain, where he had an interview with king Charles I. The king heard of his expeditions in lands rich in gold and silver and promised to support him. The Capitulación de Toledo[163] authorized Pizarro to proceed with the conquest of Peru. Pizarro was then able to convince many friends and relatives to join: his brothers Hernándo Pizarro, Juan Pizarro, Gonzalo Pizarro and also Francisco de Orellana, who would later explore the Amazon River, as well as his cousin Pedro Pizarro.

Pizarro's third and final expedition left Panama for Peru on 27 December 1530. With three ships and one hundred and eighty men, they landed near Ecuador and sailed to Tumbes, finding the place destroyed. They entered the interior and established the first Spanish settlement in Peru, San Miguel de Piura. One of the men returned with an Incan envoy and an invitation for a meeting. Since the last meeting, the Inca had begun a civil war and Atahualpa had been resting in northern Peru following the defeat of his brother Huáscar. After marching for two months, they approached Atahualpa. He refused the Spanish, saying he would be "no man's tributary". There were fewer than 200 Spanish to his 80,000 soldiers, but Pizarro attacked and won against the Incan army in the Battle of Cajamarca, taking Atahualpa captive at the so-called ransom room. Despite fulfilling his promise of filling one room with gold and two with silver, he was convicted for killing his brother and plotting against Pizarro, and was executed.

In 1533, Pizarro invaded Cuzco with indigenous troops and wrote to King Charles I:

This city is the greatest and the finest ever seen in this country or anywhere in the Indies ... it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would be remarkable even in Spain.[164]

— Francisco Pizarro

After the Spanish had sealed the conquest of Peru, Jauja in fertile Mantaro Valley was established as Peru's provisional capital, but it was too far up in the mountains, and Pizarro founded the city of Lima on 18 January 1535, which Pizarro considered one of the most important acts in his life.

Remove ads

Major new trade routes (1542–1565)

Summarize

Perspective

In 1543, three Portuguese traders accidentally became the first Westerners to reach and trade with Japan. According to Fernão Mendes Pinto, who claimed to be in this journey, they arrived at Tanegashima, where the locals were impressed by firearms that would be immediately made by the Japanese on a large scale.[165]

The Spanish conquest of the Philippines was ordered by Philip II of Spain, and Andrés de Urdaneta was the designated commander. Urdaneta agreed to accompany the expedition but refused to command and Miguel López de Legazpi was appointed instead. The expedition set sail in November 1564.[166] After spending some time on the islands, Legazpi sent Urdaneta back to find a better return route. Urdaneta set sail from San Miguel on the island of Cebu on 1 June 1565, but was obliged to sail as far as 38 degrees North latitude to obtain favorable winds.

He reasoned that the trade winds of the Pacific might move in a gyre as the Atlantic winds did. If in the Atlantic, ships made the Volta do mar to pick up winds that would bring them back from Madeira, then, he reasoned, by sailing far to the north before heading east, he would pick up trade winds to bring him back to North America. His hunch paid off, and he hit the coast near Cape Mendocino, California, then followed the coast south. The ship reached the port of Acapulco, on 8 October 1565, having traveled 12,000 miles (19,000 kilometres) in 130 days. Fourteen of his crew died; only Urdaneta and Felipe de Salcedo, nephew of López de Legazpi, had strength enough to cast the anchors.

Thus, a cross-Pacific Spanish route was established, between Mexico and the Philippines. For a long time, these routes were used by the Manila galleons, thereby creating a trade link joining China, the Americas, and Europe via the combined trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic routes.

Remove ads

Northern European involvement (16th–17th centuries)

Summarize

Perspective

European nations outside Iberia did not recognize the Treaty of Tordesillas between Portugal and Castile, nor did they recognize Pope Alexander VI's donation of the Spanish finds in the New World. France, the Netherlands and England each had a long maritime tradition and had been engaging in privateering. Despite Iberian protections, the new technologies and maps soon made their way north.

After the marriage of Henry VIII of England and Catherine of Aragon failed to produce a male heir and Henry failed to obtain a papal dispensation to annul his marriage, he broke with the Roman Catholic Church and established himself as head of the Church of England. This added religious conflict to political conflict. When much of The Netherlands became Protestant, it sought political and religious independence from Catholic Spain. In 1568, the Dutch rebelled against the rule of Philip II of Spain leading to the Eighty Years' War. The war between England and Spain also broke out. In 1580, Philip II became King of Portugal, as heir to its Crown. Although he ruled Portugal and its empire as separate from the Spanish Empire, the union of the crowns produced a Catholic superpower, which England and the Netherlands challenged.

In the eighty-year Dutch War of Independence, Philip's troops conquered the important trading cities of Bruges and Ghent. Antwerp, then the most important port in the world, fell in 1585.[citation needed] The Protestant population was given two years to settle affairs before leaving the city.[167] Many settled in Amsterdam. Those were mainly skilled craftsmen, rich merchants of the port cities and refugees that fled religious persecution, particularly Sephardi Jews from Portugal and Spain and, later, the Huguenots from France. The Pilgrim Fathers also spent time there before going to the New World. This mass immigration was an important driving force: a small port in 1585, Amsterdam quickly transformed into one of the most important commercial centres in the world. After the failure of the Spanish Armada in 1588, there was a huge expansion of maritime trade even though the defeat of the English Armada would confirm the naval supremacy of the Spanish navy over the emergent competitors.

Dutch maritime power rose quickly as Dutch sailors, skilled in navigation and mapmaking, engaged with Portuguese voyages. In 1592, Cornelis de Houtman gathered information on the Spice Islands in Lisbon. The same year, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten published a detailed travel report in Amsterdam, providing navigation instructions for reaching the East Indies and Japan.[168] Following this, Houtman led the Dutch's first exploratory voyage, discovering a new route from Madagascar to the Sunda Strait and securing a treaty with the Banten Sultan. The Dutch also demonstrated their maritime strength by seizing Malacca from Portugal in 1641, following a series of battles that began in 1602.

Dutch and British interest, fed on new information, led to a movement of commercial expansion, and the foundation of English (1600), and Dutch (1602) chartered companies. Dutch, French, and English sent ships which flouted the Portuguese monopoly, concentrated mostly on the coastal areas, which proved unable to defend against such a vast and dispersed venture.[169]

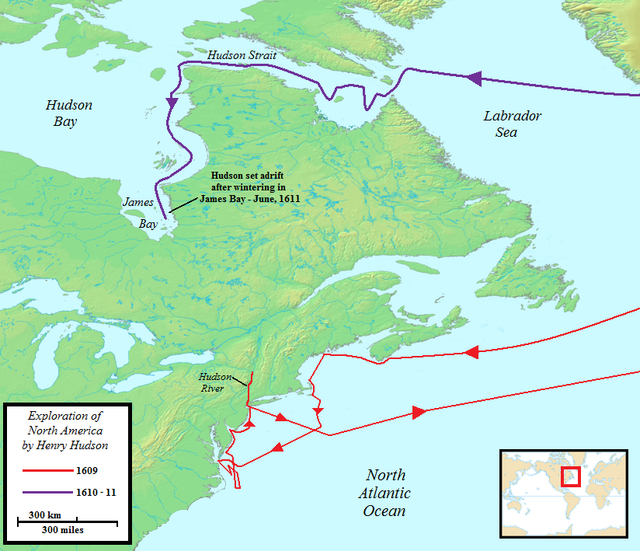

Exploring North America

The 1497 English expedition authorized by Henry VII of England was led by Italian Venetian John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto); it was the first of a series of French and English missions exploring North America. Mariners from the Italian peninsula played an important role in early explorations, most especially Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus. With its major conquests of central Mexico and Peru and discoveries of silver, Spain put limited efforts into exploring the northern part of the Americas; its resources were concentrated in Central and South America where more wealth had been found.[170] These other European expeditions were initially motivated by the same idea as Columbus, namely a westerly shortcut to the Asian mainland. After the existence of "another ocean" (the Pacific) was confirmed by Balboa in 1513, there still remained the motivation of potentially finding an oceanic Northwest Passage for Asian trade.[170] This was not discovered until the early twentieth century, but other possibilities were found, although nothing on the scale of the spectacular ones of the Spanish. In the early 17th century colonists from a number of Northern European states began to settle on the east coast of North America. Between 1520 and 1521, the Portuguese João Álvares Fagundes, accompanied by couples of mainland Portugal and the Azores, explored Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (possibly reaching the Bay of Fundy on the Minas Basin[171]), and established a fishing colony on the Cape Breton Island that would last until at least the 1570s or near the end of the century.[172]