Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Nazism

German fascist ideology From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Nazism (/ˈnɑːtsiɪzəm, ˈnæt-/ ⓘNA(H)T-see-iz-əm), formally named National Socialism (NS; German: Nationalsozialismus, German: [natsi̯oˈnaːlzotsi̯aˌlɪsmʊs] ⓘ), is the far-right totalitarian ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany.[1][2][3] During Hitler's rise to power, it was frequently called Hitler Fascism and Hitlerism. The term "neo-Nazism" is applied to other far-right groups with similar ideology, which formed after World War II.

Nazism is a form of fascism,[4][5][6][7] with disdain for liberal democracy and the parliamentary system. Its beliefs include support for dictatorship,[3] fervent antisemitism, anti-communism, anti-Slavism,[8] anti-Romani sentiment, scientific racism, white supremacy, Nordicism, social Darwinism, homophobia, ableism, and eugenics. The ultranationalism of the Nazis originated in pan-Germanism and the ethno-nationalist Völkisch movement, which had been prominent within German ultranationalism since the late 19th century. Nazism was influenced by the Freikorps paramilitary groups that emerged after Germany's defeat in World War I, from which came the party's "cult of violence".[9] It subscribed to pseudo-scientific theories of a racial hierarchy,[10] identifying ethnic Germans as part of what the Nazis regarded as a Nordic Aryan master race.[11] Nazism sought to overcome social divisions and create a homogeneous German society based on racial purity. The Nazis aimed to unite all Germans living in historically German territory, gain lands for expansion under the doctrine of Lebensraum, and exclude those deemed either Community Aliens or "inferior" races (Untermenschen).

The term "National Socialism" arose from attempts to create a nationalist redefinition of socialism, as an alternative to Marxist international socialism and free-market capitalism. Nazism rejected Marxist concepts of class conflict and universal equality, opposed cosmopolitan internationalism, and sought to convince the social classes in German society to subordinate their interests to the "common good". The Nazi Party's precursor, the pan-German nationalist and antisemitic German Workers' Party, was founded in 1919. In the 1920s, the party was renamed the National Socialist German Workers' Party to appeal to left-wing workers,[12] a renaming that Hitler initially opposed.[13] The National Socialist Program was adopted in 1920 and called for a united Greater Germany that would deny citizenship to Jews, while supporting land reform and the nationalisation of some industries. In Mein Kampf ("My Struggle"), Hitler outlined the antisemitism and anti-communism at the heart of his philosophy, and his disdain for representative democracy, over which he proposed the Führerprinzip (leader principle).[14] Hitler's objectives involved eastward expansion of German territories, colonization of Eastern Europe, and promotion of an alliance with Britain and Italy, against the Soviet Union.

The Nazi Party won the greatest share of the vote in both Reichstag elections of 1932, making it the largest party in the legislature, albeit short of a majority. Because other parties were unable or unwilling to form a coalition government, Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933 by President Paul von Hindenburg, with the support of conservative nationalists who believed they could control Hitler. With the use of emergency presidential decrees and a change in the Weimar Constitution which allowed the Cabinet to rule by direct decree, the Nazis established a one-party state and began the Gleichschaltung (process of Nazification). The Sturmabteilung (SA) and the Schutzstaffel (SS) functioned as the paramilitary organisations of the party. Hitler purged the party's more radical factions in the 1934 Night of the Long Knives. After Hindenburg's death in August 1934, Hitler became head of both state and government, as Führer und Reichskanzler. Hitler was now the dictator of Nazi Germany, under which Jews, political opponents and other "undesirable" elements were marginalised, imprisoned or murdered. During World War II, millions – including two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe – were exterminated in a genocide known as the Holocaust. Following Germany's defeat and discovery of the full extent of the Holocaust, Nazi ideology became universally disgraced. It is widely regarded as evil, with only a few fringe racist groups, usually referred to as neo-Nazis, describing themselves as followers of National Socialism. Use of Nazi symbols is outlawed in many European countries, including Germany and Austria.

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

The full name of the Nazi Party was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German for 'National Socialist German Workers' Party') and they officially used the acronym NSDAP. The renaming of the German Workers' Party (DAP) to the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) was partially driven by a desire to use both left- and right-wing terminology, with "Socialist" and "Workers'" appealing to the left, and "National" and "German" appealing to the right.[15]

The term "nazi" had been in use before the rise of the NSDAP as a colloquial and derogatory word for a backwards farmer or peasant. It characterised an awkward, clumsy person, a yokel. It was a hypocorism (pet name) of the German male name Igna(t)z (a variation of Ignatius), which was common in Bavaria, where the NSDAP originated.[16][17]

In the 1920s, labour movement opponents of the NSDAP seized on this, and shortened the party's name, Nationalsozialistische, to the dismissive "Nazi", to associate the NSDAP with the derogatory use of this term.[18][17][19][20][21][22] This was inspired by the earlier use of the abbreviation Sozi for Sozialist (German for 'Socialist').[17] The first use of the term "Nazi" by the National Socialists themselves occurred in 1926 in a publication by Joseph Goebbels called Der Nazi-Sozi ["The Nazi-Sozi"]. There, the term "Nazi-Sozi" (but not "Nazi" alone) is used as an abbreviation of "National Socialism".[23]

After the NSDAP's rise to power in the 1930s, the term "Nazi" by itself, or "Nazi Germany", "Nazi regime", etc, were popularised by German exiles, but not used in Germany. The terms spread into other languages and were brought back to Germany after World War II.[19] The NSDAP briefly adopted "Nazi" in an attempt to reappropriate it, for example in articles published in the Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter under the title Ein Nazi fährt nach Palästina in 1934.[24] But the Nazis soon gave up and avoided using the term while in power.[19][20] They typically referred to themselves as "National Socialists" and their movement as "National Socialism". A compendium of Hitler's conversations in 1941-44 entitled Hitler's Table Talk does not contain the word "Nazi".[25] In speeches by Hermann Göring, he never used "Nazi".[26] Hitler Youth leader Melita Maschmann wrote a book about her experience entitled Account Rendered,[27] where she did not refer to herself as a "Nazi", even though writing well after World War II. In 1933, 581 members of the NSDAP answered interview questions by Professor Theodore Abel, and did not refer to themselves as "Nazis".[28]

Remove ads

Position within the political spectrum

Summarize

Perspective

The majority of scholars identify Nazism, in both theory and practice, as a form of far-right politics.[1] Far-right themes in Nazism include the argument that superior people have a right to dominate, and purge society of supposed inferior elements.[29] Adolf Hitler and other proponents denied that Nazism was left or right, and instead portrayed it as syncretic, combining elements from across the political spectrum.[30][31] In Mein Kampf, Hitler attacked both left-wing and right-wing politics in Germany, saying:

Today our left-wing politicians in particular are constantly insisting that their craven-hearted and obsequious foreign policy necessarily results from the disarmament of Germany, whereas the truth is that this is the policy of traitors ... But the politicians of the Right deserve exactly the same reproach. It was through their miserable cowardice that those ruffians of Jews who came into power in 1918 were able to rob the nation of its arms.[32]

In a 1922 speech, Hitler stated:

...do not imagine that the people will forever go with the middle party, the party of compromises; one day it will turn to those who have most consistently foretold the coming ruin and have sought to dissociate themselves from it. And that party is either the Left: and then God help us! for it will lead us to complete destruction—to Bolshevism, or else it is a party of the Right which at the last, when the people is in utter despair, when it has lost all its spirit and has no longer any faith in anything, is determined for its part ruthlessly to seize the reins of power—that is the beginning of resistance...[33]

Hitler at times redefined socialism. When George Sylvester Viereck interviewed him in 1923 for the American Monthly and asked why he referred to his party as 'socialists' he replied:

Socialism is the science of dealing with the common weal. Communism is not Socialism. Marxism is not Socialism. The Marxians have stolen the term and confused its meaning. I shall take Socialism away from the Socialists. Socialism is an ancient Aryan, Germanic institution. Our German ancestors held certain lands in common. They cultivated the idea of the common weal. Marxism has no right to disguise itself as socialism. Socialism, unlike Marxism, does not repudiate private property. Unlike Marxism, it involves no negation of personality, and unlike Marxism, it is patriotic.[34]

In 1929, Hitler gave a speech to Nazi leaders and simplified 'socialism' to mean, "Socialism! That is an unfortunate word altogether... What does socialism really mean? If people have something to eat and their pleasures, then they have their socialism."[35] When asked in an interview in 1934 whether he supported the "bourgeois right-wing", Hitler claimed Nazism was not exclusively for any class and indicated it favoured neither the left nor the right, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps" by stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism."[36]

Historians regard the equation of Nazism as "Hitlerism" as too simplistic, as the term was used prior to the rise of Hitler and the Nazis. Ideologies incorporated into Nazism were already well established in parts of German society long before World War I.[37] The Nazis were strongly influenced by the post–World War I far-right, which held common beliefs such as anti-Marxism, anti-liberalism and antisemitism, along with nationalism, contempt for the Treaty of Versailles and condemnation of the Weimar Republic for signing the armistice in 1918 and later the treaty.[38] An inspiration for the Nazis were the far-right nationalist Freikorps, paramilitary organisations that engaged in political violence after World War I.[38] Initially, the post–World War I far-right was dominated by monarchists, but the younger generation, associated with völkisch nationalism, was more radical and did not express any emphasis on restoration of the monarchy.[39] This younger generation desired to dismantle the Weimar Republic, and create a new, radical and strong state, based upon a martial ruling ethic that could revive the "Spirit of 1914" which was associated with national unity (Volksgemeinschaft).[39]

The Nazis, the far-right monarchists, the reactionary German National People's Party (DNVP) and others, such as monarchist army officers and several prominent industrialists, formed an alliance in opposition to the Weimar Republic in October 1931, in Bad Harzburg, officially known as the "National Front", but referred to as the Harzburg Front.[40] The Nazis stated the alliance was purely tactical and continued to have differences with the DNVP. After the elections of July 1932, the alliance broke down when the DNVP lost many seats in the Reichstag. The Nazis denounced them as "an insignificant heap of reactionaries".[41] The DNVP responded by denouncing the Nazis for their "socialism", street violence and the "economic experiments" that would take place if the Nazis gained power.[42] However, amidst an inconclusive situation in which conservative politicians Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher were unable to form governments without the Nazis, Papen proposed to President Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as Chancellor at the head of a government formed primarily of conservatives, with only three Nazi ministers.[43][44] Hindenburg did so, and Hitler was able to establish a Nazi one-party dictatorship.[45]

Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had been forced to abdicate amidst an attempted communist revolution in Germany, initially supported the Nazis. His sons became members of the Party hoping that in exchange, the Nazis would permit restoration of the monarchy.[46] Hitler dismissed the possibility, calling it "idiotic."[47] Wilhelm grew to distrust Hitler and was appalled at the Kristallnacht of 1938.[48] The former emperor denounced the Nazis as a "bunch of shirted gangsters" and "a mob ...led by a thousand liars or fanatics."[49]

There were factions within the Nazi Party, both conservative and radical.[50] The conservative Nazi Hermann Göring urged Hitler to conciliate with capitalists and reactionaries.[50] Other conservative Nazis included Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich.[51] Meanwhile, the radical Nazi Joseph Goebbels opposed capitalism, viewing it as having Jews at its core and he stressed the need for the Party to emphasise both a proletarian and national character. Those views were shared by Otto Strasser, who later left the Party and formed the Black Front in the belief Hitler had betrayed the party's socialist goals by endorsing capitalism.[50]

When the Nazi Party emerged from obscurity to become a political force after 1929, the conservative faction rapidly gained more influence, as wealthy donors took an interest in the Nazis, as a potential bulwark against communism.[52] The Party had previously been financed from membership dues, but after 1929 its leadership sought donations from industrialists, and Hitler began holding many fundraising meetings with business leaders.[53] In the midst of the Great Depression, facing economic ruin and the possibility of a Communist or Social Democrat government, business turned to Nazism as a way out, as it promised to support, rather than attack, business interests.[54] By January 1933, the Party had secured the support of important sectors of industry, mainly among steel and coal producers, insurance, and the chemical industry.[55]

Large segments of the Party, particularly among the members of the Sturmabteilung (SA), were committed to the party's official socialist, revolutionary and anti-capitalist positions and expected a social and economic revolution when the party gained power in 1933.[56] Just before the seizure of power, there were even Social Democrats and Communists who switched sides and became known as "Beefsteak Nazis": brown on the outside and red inside.[57] The leader of the SA, Ernst Röhm, pushed for a "second revolution" (the first being the seizure of power) that would enact socialist policies. Röhm also desired that the SA absorb the much smaller German Army into its ranks, under his leadership.[56] Once the Nazis achieved power, Röhm's SA was directed by Hitler to violently suppress the parties of the left, but they also attacked individuals associated with conservative reaction.[58] Hitler saw Röhm's independent actions as violating and threatening his leadership, as well as jeopardising the regime by alienating conservative President Hindenburg and the conservative-oriented German Army.[59] This resulted in Hitler purging Röhm and other radical members of the SA in 1934, in the Night of the Long Knives.[59]

Before he joined the Bavarian Army to fight in World War I, Hitler had lived a bohemian lifestyle as a street watercolour artist in Vienna and Munich. He maintained elements of this lifestyle, going to bed late and rising in the afternoon, even after he became Chancellor and Führer.[60] His battalion was absorbed by the Bavarian Soviet Republic from 1918 to 1919, where he was elected Deputy Battalion Representative. According to historian Thomas Weber, Hitler attended the funeral of communist Kurt Eisner (a Jew), wearing a black mourning armband on one arm and a red communist armband on the other,[61] which he took as evidence that Hitler's politics had not yet solidified.[61] In Mein Kampf, Hitler never mentioned any service with the Bavarian Soviet Republic and stated that he became an antisemite in 1913, whilst in Vienna. This has been disputed by the contention that he was not an antisemite then,[62] even though he read many antisemitic tracts and journals and admired Karl Lueger, the antisemitic mayor of Vienna.[63] Hitler altered his political views in response to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 and became an antisemitic nationalist.[62]

Hitler expressed opposition to capitalism, regarding it as having Jewish origins and holding nations ransom to a parasitic cosmopolitan rentier class.[64] He also expressed opposition to communism and egalitarian forms of socialism, arguing that inequality and hierarchy are beneficial to the nation.[65] He believed communism was invented by Jews to weaken nations by promoting class struggle.[66] After seizing power, Hitler took a pragmatic position on economics, accepting private property and allowing capitalist private enterprises, so long as they adhered to the goals of the Nazi state, but not tolerating enterprises he saw as opposed to the national interest.[50]

German business leaders disliked Nazi ideology but came to support Hitler, because they saw the Nazis as an ally to promote their interests.[67] Business groups made significant financial contributions to the Nazi Party before and after the Nazi seizure of power, hoping that a Nazi dictatorship would eliminate the organised labour movement and left-wing parties.[68] Hitler actively sought to gain the support of business leaders by arguing that private enterprise is incompatible with democracy.[69]

Although he opposed communist ideology, Hitler publicly praised the Soviet Union's leader Joseph Stalin and Stalinism.[70] Hitler commended Stalin for seeking to purify the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of Jewish influences, noting Stalin's purging of Jewish communists such as Leon Trotsky.[71] While Hitler always intended to bring Germany into conflict with the Soviet Union to gain Lebensraum ("living space"), he supported a temporary strategic alliance between them, to form an anti-liberal front to defeat liberal democracies, particularly France.[70]

Hitler admired the British Empire and its colonial system as proof of Germanic superiority over "inferior" races and saw the United Kingdom as Germany's natural ally.[72][73] He wrote in Mein Kampf: "For a long time to come there will be only two Powers in Europe with which it may be possible for Germany to conclude an alliance. These Powers are Great Britain and Italy."[73]

Remove ads

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

The roots of Nazism are to be found in elements of European political culture in circulation before 1914, what Joachim Fest called the "scrapheap of ideas" then prevalent.[74][75] Martin Broszat points out:

[A]lmost all essential elements of ... Nazi ideology were to be found in the radical positions of ideological protest movements [in pre-1914 Germany]. These were: a virulent anti-Semitism, a blood-and-soil ideology, the notion of a master race, [and] the idea of territorial acquisition and settlement in the East. These ideas were embedded in a popular nationalism which was vigorously anti-modernist, anti-humanist and pseudo-religious.[75]

Brought together, the result was an anti-intellectual and politically semi-illiterate ideology lacking cohesion, a product of mass culture which allowed its followers emotional attachment and offered a simplified and easily digestible world-view, based on a political mythology for the masses.[75]

Völkisch nationalism

Hitler, along with others in the Nazi Party, were influenced by several 19th- and early 20th-century thinkers and proponents of philosophical, onto-epistemic, and theoretical perspectives on ecological anthropology, scientific racism, holistic science, and organicism regarding the constitution of complex systems and theorization of organic-racial societies.[76][77][78][79]

A significant influence was the 19th-century German nationalist philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose works served as an inspiration to Hitler and other Nazis, and whose ideas were implemented among the philosophical and ideological foundations of Nazi-oriented Völkisch nationalism.[77][77][80] In Speeches to the German Nation (1808), written amid the First French Empire's occupation of Berlin during the Napoleonic Wars, Fichte called for a German national revolution against the occupiers, making passionate speeches, arming his students for battle against the French and stressing the need for action by the German nation, so it could free itself.[81] Fichte's German nationalism was populist and opposed to traditional elites, spoke of the need for a "People's War" (Volkskrieg) and put forth concepts similar to those which the Nazis adopted.[81] Fichte promoted German exceptionalism and stressed the need for the German nation to purify itself (including purging German of French words, which the Nazis undertook).[81]

Another important figure in pre-Nazi völkisch thinking was Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, whose work—Land und Leute (Land and People, written between 1857-63)—collectively tied the organic German Volk to its native landscape and nature, a pairing in stark opposition to the mechanical and materialistic civilisation then developing as a result of industrialisation.[82] Geographers Friedrich Ratzel and Karl Haushofer borrowed from Riehl's work as did Nazi ideologues Alfred Rosenberg and Paul Schultze-Naumburg, who employed Riehl's philosophy in arguing "each nation-state was an organism that required a particular living space in order to survive".[83] Riehl's influence is discernible in the Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) philosophy introduced by Oswald Spengler, which the Nazi agriculturalist Walther Darré and other prominent Nazis adopted.[84][85]

Völkisch nationalism denounced soulless materialism, individualism and secularised urban industrial society, while advocating a "superior" society based on ethnic German "folk" culture and "blood".[86] It denounced foreigners and foreign ideas and declared that Jews, Freemasons and others were "traitors to the nation" and unworthy of inclusion.[87] Völkisch nationalism saw the world in terms of natural law and romanticism and viewed societies as organic, extolling the virtues of rural life, condemning the neglect of tradition and decay of morals, denounced the destruction of the natural environment and condemned "cosmopolitan" cultures such as Jews and Romani.[88]

The first party that attempted to combine nationalism and socialism was the (Austria-Hungary) German Workers' Party, which aimed to solve the conflict between the Austrian Germans and Czechs in the multi-ethnic Austrian Empire, then part of Austria-Hungary.[89] In 1896 the German politician Friedrich Naumann formed the National-Social Association, which aimed to combine German nationalism and a non-Marxist form of socialism together; the attempt turned out to be futile and the idea of linking nationalism with socialism quickly became equated with antisemites, extreme German nationalists and the völkisch movement in general.[37]

During the German Empire, völkisch nationalism was overshadowed by Prussian patriotism and the federalist tradition of its component states.[90] World War I, including the end of the Prussian monarchy, resulted in a surge of revolutionary völkisch nationalism.[91] The Nazis supported such revolutionary völkisch policies[90] and claimed their ideology was influenced by the leadership and policies of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who was instrumental in founding the German Empire.[92] The Nazis declared they were dedicated to continuing the process of creating a unified German nation state.[93] While Hitler was supportive of Bismarck's creation of the German Empire, he was critical of Bismarck's moderate domestic policies.[94] On the issue of Bismarck's support of a Kleindeutschland ("Lesser Germany", excluding Austria) versus the Pan-German Großdeutschland ("Greater Germany") which the Nazis advocated, Hitler stated that Bismarck's attainment of Kleindeutschland was the "highest achievement" Bismarck could have achieved "within the limits possible at that time".[95] In Mein Kampf, Hitler presented himself as a "second Bismarck".[96]

During his youth in Austria, Hitler was politically influenced by Austrian Pan-Germanist proponent Georg Ritter von Schönerer, who advocated radical German nationalism, antisemitism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Slavic sentiment and anti-Habsburg views.[97] From von Schönerer and his followers, Hitler adopted the Heil greeting, Führer title and model of absolute party leadership.[97] Hitler was also impressed by the populist antisemitism and anti-liberal bourgeois agitation of Karl Lueger, who as mayor of Vienna during Hitler's time there used rabble-rousing oratory that appealed to the masses.[98] Unlike von Schönerer, Lueger was not a German nationalist, but a pro-Catholic Habsburg supporter and only used German nationalist notions occasionally for his agenda.[98] Although Hitler praised Lueger and Schönerer, he criticised the former for not applying a racial doctrine against the Jews and Slavs.[99]

Racial theories and antisemitism

The concept of the Aryan race, which the Nazis promoted, stems from racial theories asserting that Europeans are the descendants of Indo-Iranian settlers, people of ancient India and Persia.[100] Proponents of this based their assertion on the fact that words in European and Indo-Iranian languages have similar pronunciations and meanings.[100] Johann Gottfried Herder argued that the Germanic peoples held close racial connections to the ancient Indians and Persians, who he claimed were advanced peoples that possessed a great capacity for wisdom, nobility, restraint and science.[100] Contemporaries of Herder used the concept of the Aryan race to draw a distinction between what they deemed to be "high and noble" Aryan culture versus that of "parasitic" Semitic culture.[100]

Notions of white supremacy and Aryan racial superiority were combined in the 19th century, with white supremacists maintaining the belief that certain white people were members of an Aryan "master race" superior to other races and particularly superior to the Semitic race, which they associated with "cultural sterility".[100] Arthur de Gobineau, a French racial theorist and aristocrat, blamed the fall of the French ancien régime on racial degeneracy caused by racial intermixing, which he argued had destroyed the purity of the Aryan race, a term which he reserved for Germanic people.[101][102] Gobineau's theories, which attracted a strong following in Germany,[101] emphasised the existence of an irreconcilable polarity between Aryan (Germanic) and Jewish cultures.[100]

Aryan mysticism claimed that Christianity originated in Aryan religious traditions, and Jews had usurped the legend from Aryans.[100] Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an English-born German proponent of racial theory, supported notions of Germanic supremacy and antisemitism.[101] Chamberlain's The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899), praised Germanic peoples for their creativity and idealism while asserting that the Germanic spirit was threatened by a "Jewish" spirit of selfishness and materialism.[101] Chamberlain used his thesis to promote monarchical conservatism while denouncing democracy, liberalism and socialism.[101] The book became popular, especially in Germany.[101] Chamberlain stressed a nation's need to maintain its racial purity to prevent its degeneration and argued that racial intermingling with Jews should never be permitted.[101] In 1923, Chamberlain met Hitler, whom he admired as a leader of the rebirth of the free spirit.[103] Madison Grant's The Passing of the Great Race (1916) advocated Nordicism and proposed that a eugenics program should be implemented to preserve the purity of the Nordic race. After reading it, Hitler called it "my Bible".[104]

In Germany, the belief that Jews were economically exploiting Germans became prominent due to the ascendancy of wealthy Jews into prominent positions upon the unification of Germany in 1871.[105] From 1871 to the early 20th century, German Jews were overrepresented in Germany's upper and middle classes, and underrepresented in Germany's lower classes, particularly in agricultural and industrial labour.[106] German Jewish financiers and bankers played a key role in Germany's economic growth from 1871 to 1913 and benefited enormously. In 1908, amongst the 29 wealthiest German families with fortunes of up to 55 million marks, five were Jewish and the Rothschilds were the second wealthiest.[107] The predominance of Jews in Germany's banking, commerce and industry sectors was high, even though Jews accounted for only 1% of the population.[105] Their overrepresentation in these sectors fuelled resentment, among non-Jewish Germans, during economic crises.[106] The 1873 stock market crash, and ensuing depression, resulted in attacks on alleged Jewish economic dominance and antisemitism increased.[106] In the 1870s, German völkisch nationalism began to adopt antisemitic and racist themes and was adopted by radical right political movements.[108]

Radical antisemitism was promoted by prominent advocates of völkisch nationalism, including Eugen Diederichs, Paul de Lagarde and Julius Langbehn.[88] De Lagarde called the Jews a "bacillus, the carriers of decay...who pollute every national culture ... and destroy all faiths with their materialistic liberalism" and he called for the extermination of the Jews.[109] Langbehn called for a war of annihilation against the Jews, and his genocidal policies were later published by the Nazis and given to soldiers during World War II.[109] One antisemitic ideologue of the period, Friedrich Lange, even used the term "National Socialism" to describe his anti-capitalist take on the völkisch nationalist template.[110]

Johann Fichte accused Jews in Germany of being a "state within a state" that threatened German national unity.[81] Fichte promoted two options to address this. His first was the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine, so the Jews could be impelled to leave Europe.[111] His second was violence against Jews and he said the goal would be "to cut off all their heads in one night, and set new ones on their shoulders, which should not contain a single Jewish idea".[111]

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1912) is an antisemitic forgery created by the secret service of the Russian Empire, the Okhrana. Many antisemites believed it was real and it became popular after World War I.[112] The Protocols claimed there was a secret international Jewish conspiracy to take over the world.[113] Hitler had been introduced to The Protocols by Alfred Rosenberg, and from 1920 he focused his attacks by claiming Judaism and Marxism were directly connected, that Jews and Bolsheviks were one and the same, and that Marxism was a Jewish ideology-this became known as "Jewish Bolshevism".[114] Hitler believed The Protocols were authentic.[115]

During his life in Vienna between 1907-13, Hitler became fervently anti-Slavic.[116][117][118][119] Prior to gaining power, Hitler blamed moral degradation on Rassenschande ("racial defilement"), a way to assure followers of his antisemitism, which had been toned down for popular consumption.[120] Prior to the induction of the Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935 by the Nazis, many German nationalists supported laws to ban Rassenschande between Aryans and Jews as racial treason.[120] Even before the laws were passed, the Nazis banned sex and marriages between party members and Jews.[121] Party members found guilty of Rassenschande were severely punished; some even sentenced to death.[122]

The Nazis claimed Bismarck was unable to complete national unification because Jews had infiltrated parliament, and claimed Nazi abolition of parliament had ended this obstacle.[92] Using the stab-in-the-back myth, the Nazis accused Jews—and other populations who it considered non-German—of possessing extra-national loyalties, thereby exacerbating German antisemitism about the Judenfrage (the Jewish Question), the far-right canard popular when the ethnic völkisch movement and its politics of Romantic nationalism for establishing a Großdeutschland, was strong.[123][124]

Nazism's racial positions may have developed from views of biologists of the 19th century, including French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, through Ernst Haeckel's idealist version of Lamarckism and the father of genetics, German botanist Gregor Mendel.[125] Haeckel's works were later condemned by the Nazis as inappropriate for "National-Socialist formation and education in the Third Reich". This may have been because of his "monist" atheistic, materialist philosophy, which the Nazis disliked, along with his friendliness to Jews, opposition to militarism and support for altruism.[126] Unlike Darwinian theory, Lamarckian theory ranked races in a hierarchy of evolution from apes. Darwinian theory did not grade races in a hierarchy of higher or lower evolution from apes, but simply stated that all humans had progressed in their evolution from apes.[125] Many Lamarckians viewed "lower" races as having been exposed to debilitating conditions for too long for any significant "improvement" to take place in the near future.[127] Haeckel used Lamarckian theory to describe the existence of interracial struggle and put races on a hierarchy of evolution, ranging from wholly human to subhuman.[125]

Mendelian inheritance, or Mendelism, was supported by the Nazis, as well as eugenicists. Mendelian inheritance declared that genetic traits and attributes were passed from one generation to another.[128] Eugenicists used Mendelian inheritance theory to demonstrate the transfer of biological illness and impairments from parents to children, including mental disability, whereas others also used Mendelian theory to demonstrate the inheritance of social traits, with racialists claiming a racial nature behind certain traits, such as inventiveness or criminal behaviour.[129]

Use of the American racist model

Hitler and Nazi legal theorists were inspired by America's institutional racism and saw it as the model to follow. They saw it as a model for the expansion of territory and elimination of indigenous inhabitants therefrom, for laws denying full citizenship for African Americans, which they wanted to implement against Jews, and for racist immigration laws banning "inferior" races. In Mein Kampf, Hitler extolled America as the only example of a country with racist ("völkisch") citizenship statutes in the 1920s, and Nazi lawyers made use of American models in crafting laws for Nazi Germany.[130] US citizenship laws and anti-miscegenation laws directly inspired the two principal Nuremberg Laws—the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law.[130]

Response to World War I and Italian Fascism

During World War I, German sociologist Johann Plenge spoke of the rise of a "National Socialism" in Germany within what he termed the "ideas of 1914" that were a declaration of war against the "ideas of 1789", the French Revolution.[131] According to Plenge, the "ideas of 1789" which included the rights of man, democracy, individualism and liberalism were being rejected in favour of "the ideas of 1914", which included the "German values" of duty, discipline, law and order.[131] Plenge believed ethnic solidarity (Volksgemeinschaft) would replace class division and "racial comrades" would unite to create a socialist society in the struggle of "proletarian" Germany, against "capitalist" Britain.[131] He believed the "Spirit of 1914" manifested itself in the concept of the "People's League of National Socialism".[132] This National Socialism was a form of state socialism that rejected the "idea of boundless freedom" and promoted an economy that would serve the whole of Germany, under the leadership of the state.[132] This National Socialism was opposed to capitalism due to the components that were against "the national interest", but insisted National Socialism would strive for greater efficiency in the economy.[132] Plenge advocated an authoritarian, rational ruling elite to develop National Socialism through a hierarchical technocratic state,[133] and his ideas were part of the basis for Nazism.[131]

Oswald Spengler, a German cultural philosopher, was a major influence on Nazism, although after 1933 he became alienated from it and was condemned by the Nazis for criticising Hitler.[134] Spengler's conception of national socialism and several of his political views were shared by the Nazis and the Conservative Revolutionary movement.[135]

Spengler's The Decline of the West (1918), written during the end of World War I, addressed the supposed decadence of European civilisation, which he claimed was caused by atomising and irreligious individualisation and cosmopolitanism.[134] Spengler's thesis was that a law of historical development of cultures existed involving a cycle of birth, maturity, ageing and death when they reached their final form of civilisation.[134] Upon reaching civilisation, a culture will lose its creative capacity and succumb to decadence until the emergence of "barbarians" creates a new epoch.[134] Spengler considered the Western world as having succumbed to decadence of intellect, money, cosmopolitan urban life, irreligious life, atomised individualisation and believed it was at the end of its biological and "spiritual" fertility.[134] He believed the "young" German nation as an imperial power would inherit the legacy of Ancient Rome, lead a restoration of value in "blood" and instinct, while the ideals of rationalism would be revealed as absurd.[134]

Spengler's notions of "Prussian socialism" as described in his book Preussentum und Sozialismus ("Prussiandom and Socialism", 1919), influenced Nazism and the Conservative Revolutionary movement.[135] Spengler wrote: "The meaning of socialism is that life is controlled not by the opposition between rich and poor, but by the rank that achievement and talent bestow. That is our freedom, freedom from the economic despotism of the individual".[135] Spengler adopted the anti-English ideas addressed by Plenge and Sombart during World War I that condemned English liberalism and English parliamentarianism while advocating a national socialism that was free from Marxism and that would connect the individual to the state through corporatist organisation.[134] Spengler claimed that socialistic Prussian characteristics existed across Germany, including creativity, discipline, concern for the greater good, productivity and self-sacrifice.[136] He prescribed war as a necessity by saying: "War is the eternal form of higher human existence and states exist for war: they are the expression of the will to war".[137]

Spengler's definition of socialism did not advocate a change to property relations.[135] He denounced Marxism for seeking to train the proletariat to "expropriate the expropriator", the capitalist, and then to let them live a life of leisure on this expropriation.[139] He claimed that "Marxism is the capitalism of the working class" and not true socialism.[139] According to Spengler, true socialism would be in the form of corporatism, stating that "local corporate bodies organised according to the importance of each occupation to the people as a whole; higher representation in stages up to a supreme council of the state; mandates revocable at any time; no organised parties, no professional politicians, no periodic elections".[140]

Wilhelm Stapel, an antisemitic German intellectual, used Spengler's thesis on the cultural confrontation between Jews, whom Spengler described as a Magian people, versus Europeans, as a Faustian people.[141] Stapel described Jews as a landless nomadic people in pursuit of an international culture whereby they can integrate into Western civilisation.[141] As such, Stapel claims that Jews have been attracted to "international" versions of socialism, pacifism or capitalism, because as a landless people the Jews have transgressed national cultural boundaries.[141]

For all of Spengler's influence on the movement, he was opposed to its antisemitism. He wrote in his personal papers "[H]ow much envy of the capability of other people in view of one's lack of it lies hidden in anti-Semitism!" as well as "[W]hen one would rather destroy business and scholarship than see Jews in them, one is an ideologue, i.e., a danger for the nation. Idiotic."[142]

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, who was initially the dominant figure of the Conservative Revolutionaries, influenced Nazism.[143] He rejected reactionary conservatism while proposing a new state that he called the "Third Reich", which would unite all classes under authoritarian rule.[144] Van den Bruck advocated a combination of the nationalism of the right and socialism of the left.[145]

Fascism was a major influence on Nazism. The seizure of power by fascist leader Benito Mussolini in the March on Rome in 1922 drew admiration by Hitler, who less than a month later had begun to model himself and the Nazi Party upon Mussolini and the Fascists.[146] Hitler presented the Nazis as a form of German fascism.[147][148] In 1923, the Nazis attempted a "March on Berlin" modelled after the March on Rome, which resulted in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich.[149]

Hitler spoke of Nazism being indebted to the success of Fascism's rise to power in Italy.[150] In a private conversation in 1941, Hitler said that "the brown shirt would probably not have existed without the black shirt", the "brown shirt" referring to the Nazi militia and the "black shirt" referring to the Fascist militia.[150] He said in regards to the 1920s: "If Mussolini had been outdistanced by Marxism, I don't know whether we could have succeeded in holding out. At that period National Socialism was a very fragile growth".[150]

Other Nazis—especially those associated with the party's more radical wing such as Gregor Strasser, Goebbels and Himmler—rejected Italian Fascism, accusing it of being too conservative or capitalist.[151] Alfred Rosenberg condemned Italian Fascism for being racially confused and having influences from philosemitism.[152] Strasser criticised the policy of Führerprinzip as being created by Mussolini and considered its presence in Nazism as a foreign-imported idea.[153] Throughout the relationship between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, several lower-ranking Nazis scornfully viewed fascism as a conservative movement that lacked full revolutionary potential.[153]

Remove ads

Ideology and programme

Summarize

Perspective

In his book The Hitler State (Der Staat Hitlers), historian Martin Broszat writes:

...National Socialism was not primarily an ideological and programmatic, but a charismatic movement, whose ideology was incorporated in the Führer, Hitler, and which would have lost all its power to integrate without him. ... [T]he abstract, utopian and vague National Socialistic ideology only achieved what reality and certainty it had through the medium of Hitler.

Thus, analysis of the ideology of Nazism is usually descriptive, as it was not generated from first principles, but was the result of numerous factors, including Hitler's personal views, parts of the 25-point plan, the general goals of the völkische and nationalist movements, and conflicts between party functionaries who battled "to win [Hitler] over to their respective interpretations of [National Socialism]." Once the party had been purged of divergent influences such as Strasserism, Hitler was accepted by its leadership as the "supreme authority to rule on ideological matters".[154]

Nazi ideology was based on a bio-geo-political "Weltanschauung" (worldview), advocating territorial expansionism to cultivate what it viewed as a "purified and homogeneous Aryan population." Nazi regime policies were shaped by the integration of biopolitics and geopolitics within the Hitlerian worldview, amalgamating spatial theory, practice, and imagination with biopolitics. In Hitlerism, the concepts of space and race existed in tension, forming a distinct bio-geo-political framework at the core of the Nazi project. This ideology viewed German territorial conquests and extermination of those ethnic groups it dehumanised as "untermensch" as part of a biopolitical process to establish an ideal German community.[155][156]

Nationalism and racialism

Nazism emphasised German nationalism, including irredentism and expansionism. Nazism held racial theories based upon a belief in the existence of an Aryan master race, superior to all other races. The Nazis emphasised the existence of conflict between the Aryan race and others—particularly Jews, whom the Nazis viewed as a mixed race that had infiltrated multiple societies and was responsible for exploitation and repression of the Aryan race. The Nazis also categorised Slavs as Untermensch (sub-human).[157]

Wolfgang Bialas argues the Nazis' sense of morality could be described as a form of procedural virtue ethics, as it demanded unconditional obedience to absolute virtues, with the attitude of social engineering and replaced common sense intuitions with an ideological catalogue of virtues and commands. The ideal Nazi new man was to be race-conscious, and an ideologically-dedicated warrior, who committed actions for the sake of the German race, while convinced he was acting morally. The Nazis believed an individual could only develop their capabilities and individual characteristics within the framework of the individual's racial membership; the race one belonged to determined whether or not one was worthy of moral care. The Christian concept of self-denial was replaced with the idea of self-assertion towards those deemed inferior. Natural selection and the struggle for existence were declared by the Nazis to be the most divine laws; peoples and individuals deemed inferior were said to be incapable of surviving without those deemed superior, yet by doing so they imposed a burden on the superior. Natural selection was deemed to favour the strong over the weak and the Nazis deemed that protecting those declared inferior was preventing nature from taking its course; those incapable of asserting themselves were viewed as doomed to annihilation, with the right to life being granted only to those who could survive on their own.[158]

Irredentism and expansionism

At the core of Nazi ideology was the bio-geo-political project to acquire Lebensraum ("living space") through territorial conquests.[159] The German Nazi Party supported German irredentist claims to Austria, Alsace-Lorraine, the Sudetenland, and the Polish Corridor. A key policy of the German Nazi Party was Lebensraum for the German nation based on claims Germany was facing an overpopulation crisis and expansion was needed to end overpopulation within existing territory, and provide resources necessary for its people's well-being.[160] The party publicly promoted the expansion of Germany into territories held by the Soviet Union.[161]

In Mein Kampf, Hitler stated that Lebensraum would be acquired in Eastern Europe, especially Russia.[162] In his early years as leader, Hitler claimed he would be willing to accept friendly relations with Russia on the tactical condition that Russia agree to return to the borders established by the German–Russian Treaty of Brest-Litovsk from 1918, which gave large territories held by Russia to German control in exchange for peace.[161] In 1921, Hitler had commended the Treaty as opening the possibility for restoration of relations between Germany and Russia by saying:

Through the peace with Russia the sustenance of Germany as well as the provision of work were to have been secured by the acquisition of land and soil, by access to raw materials, and by friendly relations between the two lands.

— Adolf Hitler[161]

From 1921 to 1922, Hitler called for the achievement of Lebensraum, involving a territorially-reduced Russia, as well as supporting Russian nationalists in overthrowing the Bolsheviks and establishing a new White Russian government.[161] Hitler's attitudes changed by the end of 1922, in which he then supported an alliance of Germany with Britain to destroy Russia.[161] Hitler later declared how far he intended to expand Germany into Russia:

Asia, what a disquieting reservoir of men! The safety of Europe will not be assured until we have driven Asia back behind the Urals. No organized Russian state must be allowed to exist west of that line.

— Adolf Hitler[164]

Hitler's doctrine of Lebensraum

"For the future of the German nation the 1914 frontiers are of no significance. They did not serve to protect us in the past, nor do they offer any guarantee for our defence in the future. With these frontiers the German people cannot maintain themselves as a compact unit, nor can they be assured of their maintenance. ... Against all this we, National Socialists, must stick firmly to the aim that we have set for our foreign policy; namely, that the German people must be assured the territorial area which is necessary for it to exist on this earth. ... The right to territory may become a duty when a great nation seems destined to go under unless its territory be extended. And that is particularly true when the nation in question is not some little group of negro people but the Germanic mother of all the life which has given cultural shape to the modern world."

Lebensraum policy involved expansion of Germany's borders to east of the Ural Mountains.[164][166] Hitler planned for the "surplus" Russian population living west of the Urals to be deported to the east of them.[167]

Adam Tooze explains that Hitler believed Lebensraum was vital to securing American-style consumer affluence for the German people. In this light, Tooze argues that the view the regime faced a "guns or butter" contrast is mistaken. While it is true that resources were diverted from civilian consumption to military production, Tooze explains that at a strategic level "guns were ultimately viewed as a means to obtaining more butter".[168]

While the Nazi pre-occupation with agrarian living and food production are often seen as a sign of their backwardness, Tooze explains this was in fact a driving issue in European society for at least the last two centuries. The issue of how European societies should respond to the new global economy in food was a major issue facing Europe in the early 20th century. Agrarian life in Europe was incredibly common—in the early 1930s, over 9 million Germans (a third of the workforce) still worked in agriculture and many not working in it still had allotments or otherwise grew their food. Tooze estimates half the German population in the 1930s was living in towns and villages with populations under 20,000. Many in cities still had memories of rural-urban migration—Tooze thus explains that Nazis' obsession with agrarianism was not an atavistic gloss on a modern industrial nation, but a consequence of the fact that Nazism was the product of a society still in economic transition.[169]

The Nazis obsession with food production was a consequence of the First World War. While Europe was able to avert famine with international imports, blockades brought the issue of food security back into politics, the Allied blockade of Germany in and after World War I did not cause a famine, but chronic malnutrition killed about 600,000 people in Germany and Austria. The economic crises of the interwar period meant most Germans had memories of acute hunger. Thus Tooze concludes the Nazis' obsession with acquiring land was not a case of "turning back the clock", but a refusal to accept that the result of the distribution of land, resources and population, after the imperialist wars of the 18th and 19th centuries, should be accepted as final. While the victors of the First World War had suitable agricultural land to population ratios, large empires, or both, meaning the issue of living space was closed, the Nazis, knowing Germany lacked either, refused to accept Germany's place as a medium-sized workshop dependent on imported food.[170]

The conquest of Lebensraum was an initial step[171] towards the final Nazi goal of complete German global hegemony.[172] Rudolf Hess relayed to Walter Hewel Hitler's belief that world peace could only be acquired "when one power, the racially best one, has attained uncontested supremacy". When this control would be achieved, this power could then set up for itself a world police and assure itself "the necessary living space. [...] The lower races will have to restrict themselves accordingly".[172]

Racial theories

In its racial categorisation, Nazism viewed what it called the Aryan race as the master race of the world—a race superior to all other races.[173] It viewed Aryans as being in conflict with a mixed race people, the Jews, whom the Nazis identified as a dangerous enemy. It also viewed several other peoples as dangerous to the Aryan race. To preserve the perceived racial purity of the Aryans, race laws were introduced in 1935, known as the Nuremberg Laws. At first these prevented sexual relations and marriages between Germans and Jews, and later extended to the "Gypsies, Negroes, and their bastard offspring", who were described as of "alien blood".[174][175] Such relations between Aryans (cf. Aryan certificate) and non-Aryans were now punishable under the race laws as Rassenschande or "race defilement".[174] After the war began, defilement law was extended to include all foreigners (non-Germans).[176] At the bottom of the racial scale of non-Aryans were Jews, Romanis, Slavs[177] and blacks.[178] To maintain the "purity and strength" of the Aryan race, the Nazis eventually sought to exterminate Jews, Romani, Slavs and the physically and mentally disabled.[177][179] Other groups deemed "degenerate" and "asocial" who were not targeted for extermination, but for exclusionary treatment by the Nazi state, included homosexuals, blacks, Jehovah's Witnesses and political opponents.[179] One of Hitler's ambitions at the start of the war was to exterminate, expel or enslave Slavs from Central and Eastern Europe, to acquire Lebensraum for German settlers.[180]

A Nazi-era textbook entitled Heredity and Racial Biology for Students, by Jakob Graf, described the Nazi conception of the Aryan race in a section titled "The Aryan: The Creative Force in Human History".[173] Graf claimed the original Aryans developed from Nordic peoples who invaded Ancient India, launched the development of Aryan culture that spread to ancient Persia, and were responsible for the latter's development into an empire.[173] He claimed that ancient Greek culture was developed by Nordic peoples due to paintings which showed Greeks who were tall, light-skinned, light-eyed, blond-haired.[173] He said the Roman Empire was developed by the Italics who were related to the Celts who were also Nordic.[173] He believed the vanishing of the Nordic component of the populations in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome led to their downfall.[173] The Renaissance was claimed to have developed in the Western Roman Empire because of the Migration Period that brought new Nordic blood, such as the presence of Nordic blood in the Lombards; that remnants of the Visigoths were responsible for the creation of the Spanish Empire; and that the heritage of the Franks, Goths and Germanic peoples in France was responsible for its rise as a major power.[173] He claimed the rise of the Russian Empire was due to its leadership by people of Norman descent.[173] He described the rise of Anglo-Saxon societies in North America, South Africa and Australia as being the result of the Nordic heritage of Anglo-Saxons.[173] He concluded: "Everywhere Nordic creative power has built mighty empires with high-minded ideas, and to this very day Aryan languages and cultural values are spread over a large part of the world, though the creative Nordic blood has long since vanished in many places".[173]

In Nazi Germany, the idea of creating a master race resulted in efforts to "purify" the Deutsche Volk through eugenics and its culmination was the compulsory sterilisation or involuntary euthanasia of physically or mentally disabled people. After World War II, the euthanasia programme was named Action T4.[181] The ideological justification for euthanasia was Hitler's view of Sparta as the original völkisch state and he praised Sparta's dispassionate destruction of congenitally-deformed infants to maintain racial purity.[182][183] Some non-Aryans enlisted in Nazi organisations like the Hitler Youth and the Wehrmacht, including Germans of African descent[184] and Jewish descent.[185] The Nazis began to implement "racial hygiene" policies as soon as they came to power. The 1933 "Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" prescribed compulsory sterilisation for people with a range of conditions which were thought to be hereditary, such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, Huntington's chorea and "imbecility". Sterilization was also mandated for chronic alcoholism and other forms of social deviance.[186] An estimated 360,000 people were sterilised between 1933-39. Although some Nazis suggested the programme should be extended to people with physical disabilities, such ideas had to be expressed carefully, given some Nazis had physical disabilities, such as Joseph Goebbels, who had a deformed right leg.[187]

Nazi racial theorist Hans F. K. Günther argued European peoples were divided into five races: Nordic, Mediterranean, Dinaric, Alpine and East Baltic.[11] Günther applied a Nordicist conception to justify his belief that Nordics were the highest in the racial hierarchy.[11] In Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (1922) ("Racial Science of the German People"), Günther recognised Germans as being composed of all five races, but emphasised the strong Nordic heritage among them.[188] Hitler read Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes, which influenced his racial policy.[189] Gunther believed Slavs belonged to an "Eastern race" and warned against Germans mixing with them.[190] The Nazis described Jews as being a racially mixed group of primarily Near Eastern and Oriental racial types.[191] Because such racial groups were concentrated outside Europe, the Nazis claimed Jews were "racially alien" to all European peoples and did not have deep racial roots in Europe.[191]

Günther emphasised Jews' Near Eastern racial heritage.[192] Günther identified the mass conversion of the Khazars to Judaism in the 8th century as creating two branches of the Jewish people: those of primarily Near Eastern racial heritage became the Ashkenazi Jews (that he called Eastern Jews) while those of Oriental racial heritage became the Sephardi Jews (that he called Southern Jews).[193] Günther claimed the Eastern type was composed of commercially spirited and artful traders, and held psychological manipulation skills which aided them in trade.[192] He claimed the Eastern race had been "bred not so much for the conquest and exploitation of nature as it had been for the conquest and exploitation of people".[192] Günther believed European peoples had a racially-motivated aversion to peoples of Near Eastern racial origin and their traits, and as evidence of this he showed examples of depictions of satanic figures with Near Eastern physiognomies in art.[194]

Hitler's conception of the Aryan Herrenvolk (master race) excluded most Slavs from Central and Eastern Europe. They were regarded as a race disinclined to a higher form of civilisation, which was under an instinctive force that reverted them back to nature. The Nazis regarded Slavs as having dangerous Jewish and Asiatic, meaning Mongol, influences.[196] Because of this, the Nazis declared Slavs to be Untermenschen ("subhumans").[197]

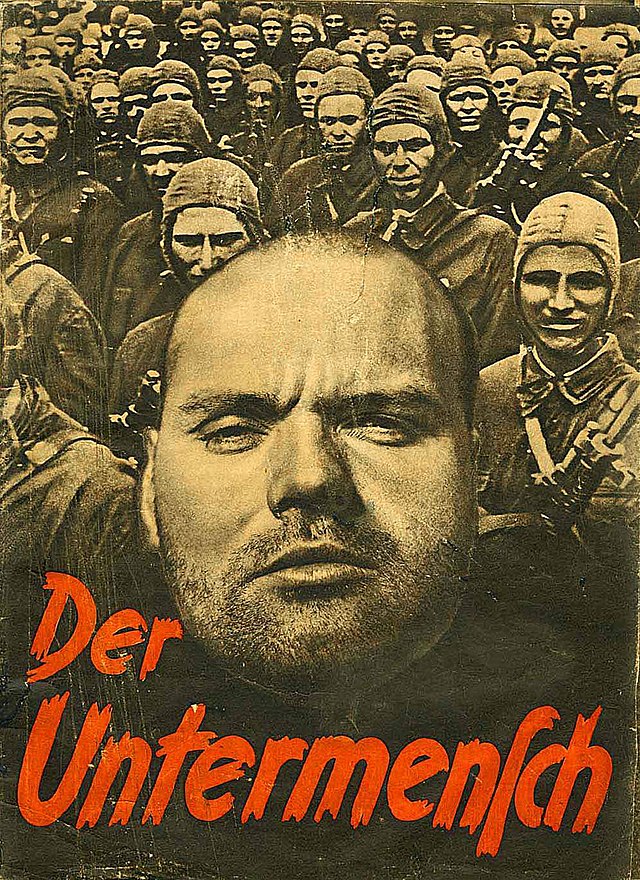

Nazi anthropologists attempted to scientifically prove the historical admixture of the Slavs who lived further East and Günther regarded the Slavs as being primarily Nordic centuries ago, but had mixed with non-Nordics.[198] Exceptions were made for a few Slavs who the Nazis saw as descended from German settlers and therefore fit to be Germanised and considered part of the Aryan master race.[199] Hitler described Slavs as "a mass of born slaves who feel the need for a master".[200] Himmler classified Slavs as "bestial untermenschen" and Jews as the "decisive leader of the Untermenschen".[201] These ideas were fervently advocated through Nazi propaganda, which indoctrinated many Germans. "Der Untermenschen", a racist brochure published by the SS in 1942, is an infamous piece of anti-Slavic propaganda.[202][203]

The Nazi notion of Slavs as inferior served as a legitimisation of their desire to create Lebensraum, where millions of Germans would be moved into conquered territories, while the Slavic inhabitants were to be annihilated, removed or enslaved.[204] Nazi Germany's policy changed towards Slavs in response to manpower shortages, forcing it to allow Slavs to serve in its military within the occupied territories, despite the fact they were considered "subhuman".[205]

Hitler declared racial conflict against Jews was necessary to save Germany from suffering under them, and he dismissed concerns:

We may be inhumane, but if we rescue Germany we have achieved the greatest deed in the world. We may work injustice, but if we rescue Germany then we have removed the greatest injustice in the world. We may be immoral, but if our people is rescued we have opened the way for morality.[206]

Propagandist Goebbels frequently employed antisemitic rhetoric to underline this view: "The Jew is the enemy and the destroyer of the purity of blood, the conscious destroyer of our race."[207]

Social class

The Nazis believed "human life consisted of eternal struggle and competition and derived its meaning from struggle and competition."[208] The Nazis saw this struggle in military terms, and advocated a society organised like an army to achieve success. They promoted the idea of a national-racial "people's community" (Volksgemeinschaft) to accomplish "the efficient prosecution of the struggle against other peoples and states."[209] Like an army, the Volksgemeinschaft was meant to consist of a hierarchy of ranks or classes, some commanding and others obeying, all working together for a common goal.[209] This concept was rooted in writings of 19th century völkisch authors who glorified medieval German society, viewing it as a "community rooted in the land and bound together by custom and tradition," in which there was no class conflict, or selfish individualism.[210] The concept of the Volksgemeinschaft appealed to many, as it was seen to affirm a commitment to a new type of society, yet offer protection from the tensions and insecurities of modernisation. It would balance individual achievement with group solidarity. Stripped of its ideological overtones, the Nazi vision of modernisation without internal conflict, and a community that offered both security and opportunity, was so potent a vision that many Germans were willing to overlook its racist and anti-Semitic essence.[211]

Nazism rejected the Marxist concept of class conflict, and it praised both German capitalists and German workers as essential to the Volksgemeinschaft. Social classes would continue to exist, but there would be no conflict between them.[212] Hitler said that "the capitalists have worked their way to the top through their capacity, and as the basis of this selection, which again only proves their higher race, they have a right to lead."[213] German business leaders co-operated in the Nazi rise to power and received benefits from the Nazi state after it was established, including high profits and state-sanctioned monopolies.[214] Celebrations and symbolism were used to encourage those engaged in physical labour, with leading National Socialists praising the "honour of labour", which fostered a sense of community (Gemeinschaft) for the German people and promoted solidarity towards the Nazi cause.[215] To win workers away from Marxism, Nazi propaganda sometimes presented its expansionist foreign policy as a "class struggle between nations."[213] Bonfires were made of school children's differently coloured caps as symbolic of the unity of social classes.[216]

In 1922, Hitler disparaged other nationalist and racialist parties as disconnected from the populace, especially working-class young people:

The racialists were not capable of drawing the practical conclusions...especially in the Jewish Question...the German racialist movement developed a similar pattern to that of the 1880s and 1890s. As in those days, its leadership gradually fell into the hands of highly honourable, but fantastically naïve men of learning, professors, district counsellors, schoolmasters, and lawyers—in short a bourgeois, idealistic, and refined class. It lacked the warm breath of the nation's youthful vigour.[217]

Nevertheless, the Nazis' voter base consisted mainly of farmers and the middle class, including groups such as Weimar government officials, teachers, doctors, clerks, self-employed businessmen, salesmen, retired officers, engineers, and students.[218] Their demands included lower taxes, higher prices for food, restrictions on department stores and consumer co-operatives, and reductions in social services and wages.[219] The need to maintain their support made it difficult for the Nazis to appeal to the working class, which often had opposite demands.[219]

From 1928, the Nazis' growth into a large political movement was dependent on middle class support, and on the public perception that it "promised to side with the middle classes and to confront the economic and political power of the working class."[220] The financial collapse of the white collar middle-class of the 1920s figured significantly in their support of Nazism.[221] Although the Nazis continued to make appeals to "the German worker", Timothy Mason concludes that "Hitler had nothing but slogans to offer the working class."[222] Conan Fischer and Detlef Mühlberger argue that while the Nazis were primarily rooted in the lower middle class, they were able to appeal to all classes and that while workers were underrepresented, they were still a substantial source of support.[223][224] H.L. Ansbacher argues working-class soldiers had the most faith in Hitler out of any occupational group.[225]

The Nazis established a norm that every worker should be semi-skilled, which was not simply rhetorical. The number of men leaving school, to work as unskilled labourers, fell from 200,000 in 1934 to 30,000 in 1939. For many working-class families, the 1930s and 40s were a time of social mobility; not by moving into the middle class, but within the blue-collar skill hierarchy.[226] The experience of workers varied considerably. Workers' wages did not increase much during Nazi rule, as the government feared wage-price inflation, and thus wage growth was limited. Prices for food and clothing rose, though costs for heating, rent and light decreased. Skilled workers were in shortage from 1936, meaning workers who engaged in vocational training could get higher wages. Benefits provided by the Labour Front were positively received, even if workers did not always believe propaganda about the Volksgemeinschaft. Workers welcomed opportunities for employment after the harsh years of the Depression, creating a belief that the Nazis had removed the insecurity of unemployment. Workers who remained discontented risked the Gestapo's informants. Ultimately, the Nazis faced a conflict between their rearmament program, which required sacrifices from workers (longer hours and a lower standard of living), versus a need to maintain the confidence of the working class. Hitler was sympathetic to the view that stressed taking further measures for rearmament, but did not fully implement them, to avoid alienating the working class.[227]

While the Nazis had substantial support amongst the middle-class, they often attacked traditional middle-class values and Hitler personally held contempt for them. This was because the traditional image of the middle class was one that was obsessed with status, material attainment and quiet, comfortable living, in opposition to the Nazi ideal of a New Man. The New Man was envisioned as a heroic figure who rejected a materialistic and private life, for a public life and pervasive sense of duty, willing to sacrifice everything for the nation. Despite the Nazis' contempt for these values, they were able to secure millions of middle-class votes. Hermann Beck argues that while some of the middle-class dismissed this as mere rhetoric, many others agreed with the Nazis. The defeat of 1918, and failures of Weimar, caused many middle-class Germans to question their own identity, thinking their values to be anachronisms and agreeing these were no longer viable. While this rhetoric would become less frequent after 1933, due to the increased emphasis on the volksgemeinschaft, its ideas would not disappear until the Nazis' overthrow. The Nazis instead emphasised that the middle-class must become staatsbürger, a publicly active and involved citizen, rather than a selfish, materialistic spießbürger, only interested in private life.[228][229]

Sex and gender

Nazi ideology advocated excluding women from politics and confining them to the spheres of "Kinder, Küche, Kirche" (Children, Kitchen, Church).[230] Many women enthusiastically supported the regime, but formed internal hierarchies.[231] Hitler's opinion was that while other eras of history had experienced the development and liberation of the female mind, the National Socialist goal was singular: it wished for them to produce children.[232] Hitler remarked about women that "with every child that she brings into the world, she fights her battle for the nation. The man stands up for the Volk, exactly as the woman stands up for the family".[233] Proto-natalist programs offered favourable loans and grants to newlyweds, and encouraged them to give birth by providing additional incentives.[234] Contraception was discouraged for racially-valuable women and abortion was forbidden by law, including prison for women who sought them, and doctors who performed them, whereas abortion for racially "undesirable" persons was encouraged.[235][236]

While unmarried until the end of the regime, Hitler often made excuses about his busy life hindering any chance for marriage.[237] Among National Socialist ideologues, marriage was valued not for moral considerations, but because it provided an optimal breeding environment. Himmler reportedly told a confidant that when he established the Lebensborn program, an organisation that would dramatically increase the birth rate of "Aryan" children through extramarital relations between women classified as racially pure and their male equals, he had only the purest male "conception assistants" in mind.[238]

Since the Nazis extended the Rassenschande ("race defilement") law to all foreigners at the beginning of the war,[176] pamphlets were issued to German women which ordered them to avoid sex with foreign workers brought to Germany and view these workers as a danger to their blood.[239] Although the law was applicable to both genders, German women were punished more severely for having sex with foreign forced labourers.[240] The Nazis issued the Polish decrees in March 1940 which contained regulations concerning the Polish forced labourers (Zivilarbeiter) brought to Germany. One regulation stated that any Pole "who has sex...with a German man or woman, or approaches them in any other improper manner, will be punished by death".[241] After the decrees were enacted, Himmler stated:

Fellow Germans who engage in sexual relations with male or female civil workers of the Polish nationality, commit other immoral acts or engage in love affairs shall be arrested immediately.[242]

The Nazis issued similar regulations against 'Eastern Workers' (Ostarbeiter), including imposition of the death penalty if they engaged in sex with German persons.[243] Heydrich issued a decree in 1942, which declared that: sex between a German woman and Russian worker or prisoner of war, would result in the Russian man being punished with death.[244] Another decree stated any "unauthorised" sex would result in the death penalty.[245] Because the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour did not permit capital punishment for race defilement, special courts were convened to allow the death penalty to be imposed.[246] Women accused of race defilement were marched through the streets with their head shaven and placards detailing their crimes around their necks[247] and those convicted of race defilement were sent to concentration camps.[239] When Himmler reportedly asked Hitler what the punishment should be for German women who were found guilty of race defilement with prisoners of war, he ordered that "every POW who has relations with a German girl or a German would be shot" and the woman should be publicly humiliated by "having her hair shorn and being sent to a concentration camp".[248]

The League of German Girls, the girls' wing of the Nazi party, instructed girls to avoid race defilement.[249] Transgender people had a variety of experiences depending on whether they were considered "Aryan" or capable of useful work.[250] Historians have noted trans people were targeted by the Nazis through legislation and sent to concentration camps.[251][252][253][254][255]

Opposition to homosexuality

After the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler promoted Himmler and the SS, who then zealously suppressed homosexuality by saying: "We must exterminate these people root and branch ... the homosexual must be eliminated".[256] In 1936, Himmler established the "Reichszentrale zur Bekämpfung der Homosexualität und Abtreibung" ("Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion").[257] Between 1937-39, the Nazi regime arrested 95,000 homosexual men.[258] Nazi ideology still viewed men who were gay as a part of the master race, but the regime attempted to force them into sexual and social conformity. Homosexuals were viewed as failing in their duty to procreate and reproduce for the Aryan nation. Gay men who would not conform were sent to concentration camps under the "Extermination Through Work" campaign.[259] As concentration camp prisoners, homosexual men were forced to wear pink triangle badges.[260][page needed]

Religion

The Nazi Party Programme of 1920 guaranteed freedom for all religious denominations which were not hostile to the State and endorsed Positive Christianity, in order to combat "the Jewish-materialist spirit".[261] Positive Christianity was a modified version of Christianity which emphasised racial purity and nationalism.[262] The Nazis were aided by theologians such as Ernst Bergmann. In his Die 25 Thesen der Deutschreligion (Twenty-five Points of the German Religion), Bergmann held the view that the Old Testament was inaccurate, along with portions of the New Testament, claimed Jesus was not a Jew but instead of Aryan origin, and Hitler was the new messiah.[262]

Hitler denounced the Old Testament as "Satan's Bible" and using components of the New Testament he attempted to prove Jesus was an Aryan and antisemite by citing passages such as John 8:44 where he noted Jesus is yelling at "the Jews", as well as saying to them "your father is the devil" and the Cleansing of the Temple, which describes Jesus' whipping of the "Children of the Devil".[263] Hitler claimed the New Testament included distortions by Paul the Apostle, who Hitler described as a "mass-murderer turned saint".[263] The Nazis displayed an original edition of Martin Luther's On the Jews and their Lies during the Nuremberg rallies.[264][265]

The Nazis were initially hostile to Catholics because most supported the German Centre Party. Catholics opposed Nazi promotion of compulsory sterilisation of those deemed inferior, and the Catholic Church forbade its members to vote for the Nazis. In 1933, extensive Nazi violence occurred against Catholics due to their association with the Centre Party, and opposition to the Nazi sterilisation laws.[266] The Nazis demanded Catholics declare their loyalty to the German state.[267] In their propaganda, the Nazis used elements of Germany's Catholic history, in particular the German Catholic Teutonic Knights and their campaigns in Eastern Europe. The Nazis identified them as "sentinels" in the East against "Slavic chaos", though beyond that symbolism, the influence of the Teutonic Knights on Nazism was limited.[268] Hitler admitted Nazis' night rallies were inspired by Catholic rituals he had witnessed during his Catholic upbringing.[269] The Nazis did seek official reconciliation with the Catholic Church and endorsed the creation of the pro-Nazi Catholic Kreuz und Adler, an organisation which advocated a form of national Catholicism that would reconcile the Catholic Church's beliefs with Nazism.[267] In July 1933, a concordat (Reichskonkordat) was signed between Nazi Germany and the Catholic Church, which in exchange for acceptance of the Catholic Church in Germany required Catholics to be loyal to the German state. The Catholic Church ended its ban on members supporting the Nazis.[267]